“What do we mean by the Revolution? The war? That was no part of the Revolution; it was only an effect and consequence of it. The revolution was in the minds of the people, and this was effected from 1760 - 1775, in the course of fifteen years, before a drop of blood was shed at Lexington.”

-John Adams letter to Thomas Jefferson, 1815, cited in Bailyn (1992, p. 1).

Abstract

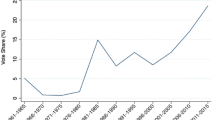

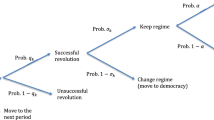

I construct a simple theoretical model that incorporates the role of ideas and contested persuasion in processes of institutional change, specifically democratization. The model helps reconcile the view that extensions of the franchise in Western Europe tended to occur as a response to the threat of revolution with the view that these occurred based on a change of social values due to the Enlightenment. In particular, the model puts forward the argument that institutional changes become possible once ideological entrepreneurs –the carriers of an alternative worldview– win an ideological contest against the holders of traditional ideas so that the rest of society adopts their worldview, and a revolutionary threat becomes credible. The model shows that the preferences of the ideological entrepreneurs are key. A revolution takes place only if they prefer it to a peaceful transition. Also, the model predicts that actual revolutions occur only when the probability of them being successful is either low or high. Finally, the ideological benefits associated with adhering to a specific ideology affect whether institutional change is peaceful or not. A strong traditional ideology generating large psychological benefits of adhering to the status quo makes it more likely that democratization occurs through revolution. On the contrary, a strong alternative ideology favoring the extension of the franchise makes it more likely that democracy emerges but has an ambiguous effect on the likelihood of a revolution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

City-states in early Mesopotamia, Ancient Greece and late Medieval Italy are possible exceptions, but even in these cases the franchise did not include slaves, women and most of the male population due to property restrictions.

Throughout the paper I denote the set of ideological entrepreneurs together with the elite by “rich”.

Przeworski (2009) distinguishes between extensions by class and by gender. The support for the threat of revolution argument is strongest for extensions by class. But, while extensions of women’s suffrage seem to be a product of electoral calculations of political parties, social unrest still has explanatory power for this type of reform.

See Palmer (1959, p. 442) for a brief presentation of the different explanations of the French Revolution that have been put forward.

A possible explanation for the timing of events is that the ideas of the Enlightenment required a relatively educated society, which could only be found towards the end of the eighteenth century. For example, Melton (2001) shows that literacy in several European countries doubled during this century.

Chaturvedi (2005) explores a similar argument within a democracy.

Throughout the paper I use the terms ideological entrepreneur, vanguard, or simply entrepreneur to refer to this subset of the rich.

See, e.g., Chapter 4 in Tullock (1987) for a discussion of the role of rich unity in the survival of autocracies.

Because they can align with the elite or the poor, it may seem that the entrepreneurs have a similar role as swing voters in probabilistic voting models. However, as will be clear below, their role is very different. First, whether they adopt a particular position is given exogenously and therefore does not depend on a choice made by them. And, second, they are the carriers of a particular position.

I include these persuasion costs even in the case of non-democracy because, as explained below, the elite and the vanguard choose their effort levels without knowing the ex-post state of the world.

The assumption of a transfer simplifies the discussion. Similar results would follow if I consider a more detailed structure in which the political system determines the tax rate governing society (as in Acemoglu and Robinson (2006)). In a non-democracy, the tax rate would be zero, which is the preferred level of the elite; in a democracy, the tax rate implemented would be the one preferred by the median voter, who is a member of the poor.

The probability of success q could be endogenous as in Bueno De Mesquita (2010). As explained above, I keep it exogenous to isolate a different mechanism of collective action based on the poor’s belief updating and their associated decision to support a democratic transition.

Throughout the paper I define preferences against non-democracy and those in favor of revolution as strict inequalities.

This is a simplified version of the more general power law form discussed in Skaperdas and Vaidya (2012): \(L^E(h_e,h_v)=\xi \left( \frac{h_e}{h_v}\right) ^\omega\), where \(\xi , \omega > 0\). The parameter \(\xi\) captures the bias that the poor have in taking account of the messages of the two parties and \(\omega\) is a measure of the sensitivity of the poor to the messages (and through these messages to the resources used by the elite and the vanguard). \(\omega =1\) is assumed for simplicity. \(\xi =1\) follows from the fact that there are two opposing forces affecting the potential bias of the poor. On the one hand, the force of tradition and theology-driven beliefs might lead to a bias in favor of the elites (\(\xi <1\)). On the other hand, as pointed for instance by Mullainathan and Shleifer (2005), people tend to appreciate stories consistent with their beliefs. And, since by definition the message carried by the ideological entrepreneurs is aligned with the plight of the poor, they might favor them (\(\xi >1\)).

Note that this condition is consistent with the poor’s decision rule as specified in proposition 3.

See the detailed analysis of the French Revolution as a long process of de-institutionalization and re-institutionalization by Vahabi et al. (2020).

References

Acemoglu, D., & Jackson, M. O. (2015). History, expectations, and leadership in the evolution of social norms. The Review of Economic Studies, 82(2), 423–456. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdu039

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2000). Why did the west extend the Franchise? Democracy, inequality, and growth in historical perspective. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115(4), 1167–1199. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355300555042

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2001). A theory of political transitions. American Economic Review, 91(4), 938–963. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.91.4.938

Acemoglu, D. & Robinson, J.A. (2006). Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy. New YorkCambridge University Press.

Aidt, T. S., & Franck, R. (2013). How to get the snowball rolling and extend the franchise: Voting on the Great Reform Act of 1832. Public Choice, 155, 229–250. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-011-9911-y

Aidt, T. S., & Franck, R. (2015). Democratization under the threat of revolution: Evidence From the great reform Act of 1832. Econometrica, 83(2), 505–547. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA11484

Aidt, T.S. & Jensen, P.S. (2014). Workers of the world, unite! Franchise extensions and the threat of revolution in Europe, 1820-1938.

Aidt, T. S., & Jensen, P. S. (2014). Workers of the world, unite! Franchise extensions and the threat of revolution in Europe, European Economic Review, 72, 52–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2014.08.001

Aoki, M. (2001). Toward a comparative institutional analysis. MAMIT Press.

Aoki, M. (2008). Analysing institutional change: integrating endogenous and exogenous views. L.M. Kornai J. & G. Roland (Eds.), Institutional Change and Economic Behaviour (113–133).

Ash, E., Mukand, S., Rodrik, D. (2021). Economic Interests, Worldviews, and Identities: Theory and Evidence on Ideational Politics. NBER working paper 29474.

Bailyn, B. (1992). The ideological origins of the American revolution. MAHarvard University Press.

Bénabou, R., & Tirole, J. (2016). Mindful economics: The production, consumption, and value of beliefs. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 30(3), 141–164. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.30.3.141

Boix, C. (2003). Democracy and Redistribution. University Press.

Bromberg-Martin, E. S., & Sharot, T. (2020). The Value of Beliefs. Neuron, 106(4), 561–565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2020.05.001

Buchheim, L., & Ulbricht, R. (2020). A quantitative theory of political transitions. The Review of Economic Studies, 87(4), 1726–1756. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdz057

Bueno De Mesquita, E. (2010). Regime change and revolutionary entrepreneurs. American Political Science Review, 104(3), 446–466. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055410000274

Caillaud, B., & Tirole, J. (2007). Consensus building: how to persuade a group. American Economic Review, 97(5), 1877–1900. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.97.5.1877

Chaturvedi, A. (2005). Rigging elections with violence. Public Choice, 125(1), 189–202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-005-3415-6

Church, W. F. (1964). The influence of the enlightenment on the French revolution: Creative, Disastrous, or Non-existent? Heath and Company.

Congleton, R. D. (2007). From royal to parliamentary rule without revolution: The economics of constitutional exchange within divided governments. European Journal of Political Economy, 23(2), 261–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2007.04.002

Conley, J. P., & Temimi, A. (2001). Endogenous enfranchisement when groups’ preferences conflict. Journal of Political Economy, 109(1), 79–102. https://doi.org/10.1086/318601

Cramer, C. (2003). Does inequality cause conflict? Journal of International Development, 15(4), 397–412. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.992

DellaVigna, S., Enikolopov, R., Mironova, V., Petrova, M., & Zhuravskaya, E. (2014). Cross-border media and nationalism: evidence from Serbian radio in Croatia. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 6(3), 103–32. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.6.3.103

DellaVigna, S., & Gentzkow, M. (2010). Persuasion: Empirical evidence. Annual Review of Economics, 2(1), 643–669. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.economics.102308.124309

DellaVigna, S., & Kaplan, E. (2007). The fox news effect: Media bias and voting. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(3), 1187–1234. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.122.3.1187

Dix, R. H. (1984). Why Revolutions Succeed & Fail. Polity, 16(3), 423–446. https://doi.org/10.2307/3234558

Enikolopov, R., Petrova, M., & Zhuravskaya, E. (2011). Media and political persuasion: Evidence from Russia. American Economic Review, 101(7), 3253–85. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.101.7.3253

Epley, N., & Gilovich, T. (2016). The mechanics of motivated reasoning. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 30(3), 133–140. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.30.3.133

Finer, S.E. (1997). The History of Government from the Earliest Times: Ancient Monarchies and Empires ( 1). University Press.

Goldstone, J. A. (2001). Toward a fourth generation of revolutionary theory. Annual Review of Political Science, 4(1), 139–187. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.4.1.139

Greif, A. (2006). Institutions and the Path to the Modern Economy: Lessons from Medieval Trade. University Press.

Hobsbawm, E. (1996). The Age of Revolution: 1789-1848. Weidenfeld and Nicholson.

Israel, J.I. (2001). Radical Enlightenment: Philosophy and the Making of Modernity 1650-1750. University Press.

Israel, J.I. (2006). Enlightenment Contested: Philosophy, Modernity, and the Emancipation of Man 1670-1752. University Press.

Israel, J.I. (2009). A Revolution of the Mind: Radical Enlightenment and the Intellectual Origins of Modern Democracy. University Press.

Israel, J.I. (2011). Democratic Enlightenment: Philosophy, Revolution, and Human Rights 1750-1790. University Press.

Jack, W., & Lagunoff, R. (2006). Dynamic enfranchisement. Journal of Public Economics, 90(4), 551–572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2005.05.003

Jacob, M.C. (1981). The Radical Enlightenment: Pantheists, Freemasons and Republicans ( 3). Allen and Unwin.

Kim, W. (2007). Social insurance expansion and political regime dynamics in Europe, 1880–1945. Social Science Quarterly, 88(2), 494–514. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6237.2007.00468.x

Kuran, T. (1989). Sparks and prairie fires: A theory of unanticipated political revolution. Public Choice, 61(1), 41–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00116762

Lizzeri, A., & Persico, N. (2004). Why did the elites extend the suffrage? Democracy and the scope of government, with an application to Britain’s “Age of Reform’’. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119(2), 707–765. https://doi.org/10.1162/0033553041382175

Llavador, H., & Oxoby, R. J. (2005). Partisan competition, growth, and the Franchise. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120(3), 1155–1189. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/120.3.1155

Loewenstein, G., & Molnar, A. (2018). The renaissance of belief-based utility in economics. Nature Human Behaviour, 2(3), 166–167. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0301-z

Mantzavinos, C. (2004). Individuals, Institutions, and Markets. University Press.

Melton, J. V. H. (2001). The Rise of the Public in Enlightenment Europe. MACambridge University Press.

Möbius, M. M., Niederle, M., Niehaus, P., & Rosenblat, T. S. (2022). Managing self-confidence: Theory and experimental evidence. Management Science, 68(11), 7793–7817. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2021.4294

Montalvo, J.G. & Reynal-Querol, M. (2012). Inequality, Polarization, and Conflict. S. S. & M. Garfinkel (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of the Economics of Peace and Conflict. New YorkOxford University Press.

Mullainathan, S., Schwartzstein, J., & Shleifer, A. (2008). Coarse Thinking and Persuasion. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123(2), 577–619. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.2008.123.2.577

Mullainathan, S., & Shleifer, A. (2005). The Market for News. American Economic Review, 95(4), 1031–1053. https://doi.org/10.1257/0002828054825619

North, D. C. (1990). Institutional change and economic performance. University Press.

North, D.C. (2005). Understanding the Process of Economic Change. University Press.

North, D.C. , Wallis, J., & Weingast, B. (2009). Violence and Social Orders. University Press.

Olsson-Yaouzis, N. (2012). An evolutionary dynamic of revolutions. Public Choice, 151, 497–515. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-010-9755-x

Ostrom, E. (2008). Developing a method for analyzing institutional change. S. Batie & N. Mercuro (Eds.), Alternative Institutional Structures: Evolution and Impact (48–76). Routledge.

Palmer, R.R. (1959). Age of the Democratic Revolution: A Political History of Europe and America, 1760-1800, The Challenge ( 1). University Press.

Przeworski, A. (2009). Conquered or granted? A history of suffrage extensions. British Journal of Political Science, 392, 291–321. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123408000434

Rød, E. G., Knutsen, C. H., & Hegre, H. (2020). The determinants of democracy: A sensitivity analysis. Public Choice, 185(1), 87–111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-019-00742-z

Rodrik, D. (2014). When ideas trump interests: preferences, worldviews, and policy innovations. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28(1), 189–208. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.28.1.189

Rosendorff, B. P. (2001). Choosing Democracy. Economics & Politics, 13(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0343.00081

Sharot, T., Rollwage, M., Sunstein, C. R., & Fleming, S. M. (2023). Why and When Beliefs Change. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 18(1), 142–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/17456916221082

Skaperdas, S. & Vaidya, S. (2012). Persuasion as a contest. Economic theory,51(2),465–486, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00199-009-0497-2

Tholfsen, T.R. (1984). Ideology and Revolution in Modern Europe: An Essay on the Role of Ideas in History. University Press.

Ticchi, D. & Vindigni, A. (2008). War and Endogenous Democracy. IZA discussion paper No. 3397.

Tullock, G. (1987). Autocracy. Academic Publishers.

Vahabi, M., Batifoulier, P., & Da Silva, N. (2020). The Political Economy of Revolution and Institutional Change: the Elite and Mass Revolutions. Revue d’économie politique,130(6),855–889, https://doi.org/10.3917/redp.306.0013

Yanagizawa-Drott, D. (2014). Propaganda and conflict: Evidence from the Rwandan Genocide. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 129(4), 1947–1994. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qju020

Zaller, J.R. et al. (1992). The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion. University press.

Zimmermann, F. (2020). The dynamics of motivated beliefs. American Economic Review, 110(2), 337–363. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20180728

Acknowledgements

I am thankful to two anonymous referees and to the editor of Public Choice for very helpful and insightful comments. I am also thankful to Stergios Skaperdas and Michael McBride for detailed comments on earlier drafts of this paper, and to participants at the UC Irvine Theory, History, and Development Seminar; the UC Merced Tournaments, Contests, and Relative Performance Evaluation Conference; the University of Tampere Institutions in Context: Dictatorship and Democracy Conference; and the Max Plank Institute for Tax Law and Public Finance Tax Day.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix A Proofs

Appendix A Proofs

Proof of Proposition 1

Given the structure of utilities in the different states, the elite’s preferred outcome is the status quo. Hence, democracy is only possible under the threat of revolution. From Assumption 2, a necessary condition for a revolution to be feasible is that the entrepreneurs prefer it to the status quo. This occurs if \(q > q^*\). It is also necessary that the poor prefer a revolution to the status quo, i.e., that \(V_p^R(I^E) > V_p^N\), or that \(q > \frac{y_p^N}{y_p^R+I^E\bar{y}} = \frac{y_p^N}{y_v^R+I^E\bar{y}}\), where the last equality follows from the assumption that the poor and the entrepreneurs share income equally in a revolution. Now, the fact that \(y_v^N > y_p^N\) implies that \(q^* > \frac{y_p^N}{y_v^R+I^E\bar{y}}\) (see eq. (10)), and thus if \(q > q^*\) the poor’s revolutionary constraint is automatically satisfied. The proposition thus follows. \(\square\)

Proof of Proposition 2

Recall from Assumption 1 that peaceful democratization occurs only if both the elite and the vanguard choose to extend the franchise. Assumption 4 implies that \(q^* < q^{**}\). Also, from eq. (11), the entrepreneurs prefer a peaceful democratization to revolution as long as \(q^* < q \le q^{**}\). If \(q > q^{**}\), they prefer a revolution. Finally, from eq. (12), the elites prefer a peaceful democratization as long as \(q \ge {\hat{q}}\); and they prefer a revolution otherwise.

Thus, when \({\hat{q}} < q^{**}\), \(\exists\) q s.t. \({\hat{q}} \le q \le q^{**}\) for which both the elite and the vanguard prefer to extend the franchise. The first inequality guarantees that the elites prefer a peaceful democratization, while the second one guarantees that the vanguard prefers this outcome. Peaceful democratization thus follows. The range of q for which a revolution takes place follows directly from eqs. (11) and (12). This concludes the first part of the Proposition.

The second part of the Proposition follows simply from noting that when \({\hat{q}} \ge q^{**}\), there is no q for which both the elite and the vanguard agree to extend the franchise. As a consequence, only a revolution is possible. \(\square\)

Proof of Corollary 1

The first part follows directly from Proposition 2. The second part follows from eq. (12). From here it is clear that \(\frac{\partial {\hat{q}}}{\partial I^T\bar{y}} = \frac{y_e^D}{(y_e^R+I^T{\bar{y}})^2} > 0\). In words, an increase in \(I^T\bar{y}\) leads to an increase in \({\hat{q}}\). Recall, however that the range of q for which a peaceful democratization is possible is given by \({\hat{q}} \le q \le q^{**}\). Thus, when \({\hat{q}}\) increases, this range becomes smaller. \(\square\)

Proof of Proposition 3

The poor’s decision rule and the application of Bayes’ rule to the determination of the poor’s posterior beliefs that E is the right ideology as given in eq. (16) imply that: \(\frac{\pi h_v}{(1-\pi )h_e + \pi h_v} > \gamma\). For any given prior \(\pi\), this can be written as: \(\pi > \frac{\gamma h_e}{(1-\gamma )h_v + \gamma h_e}\). Given our assumption that the elite and the vanguard have a uniform distribution about \(\pi\), the probability of the poor supporting the vanguard (\(p_S^E\)) is thus given by:

which is eq. (17). \(\square\)

Proof of Proposition 4

The poor choose \(S^{E,R}\) if and only the utility derived from this choice is greater than the utility derived from choosing \(S^{T,R}\). From (18) and (19), they thus choose \(S^{E,R}\) iff:

The condition in Proposition 4 follows directly from here. \(\square\)

Proof of Proposition 5

Note first that for \(q > q^*\), the ideological entrepreneurs are willing to use resources to persuade the poor. Given the structure of the ideological contest, it follows that in this case the elite is also willing to use resources for persuasion. An ideological conflict thus takes place for this range of q.

Now, persuasion is only relevant as long as \(0< \gamma ^R < 1\), or, equivalently, as long as \(\underline{q}< q < {\bar{q}}\), where \(\underline{q} \equiv \frac{y_p^N-I^E{\bar{y}}}{y_p^R}\) and \({\bar{q}} \equiv \frac{y_p^N+I^T{\bar{y}}}{y_p^R}\).

Comparing first \(\underline{q}\) and \(q^*\), \(\underline{q} \ge q^*\) iff \(\frac{y_p^N-I^E\bar{y}}{y_p^R} \ge \frac{y_v^N}{y_v^R+I^E{\bar{y}}}\), or iff

where in the LHS I have switched \(y_p^R\) and \(y_v^R\) appropriately, since they are assumed to be equal. Since \(y_p^N < y_v^N\) and \(y_p^N < y_p^R\), the LHS in this inequality is negative, leading to a contradiction. It thus follows that \(q^* > \underline{q}\).

Comparing \(\bar{q}\) and \(q^{**}\), \({\bar{q}} \le q^{**}\) iff

From Assumption 3, \(y_p^N + I^T\bar{y} > y_p^R\) (assuming \(q=1\)) and thus in the above equation the \(LHS > 1\). On the other hand, from Assumption 5, \(y_v^R > y_v^D\) and thus the \(RHS < 1\), leading to a contradiction. Thus, \(q^{**} < \bar{q}\).

Therefore, the thresholds \(\underline{q}\) and \(\bar{q}\) for which persuasion is relevant are not binding. \(\square\)

Proof of Proposition 6

Follows directly from the comparison of the utilities in eqs. (27) and (28), as was done for the revolutionary case. \(\square\)

Proof of Proposition 7

As in the revolutionary case, persuasion is relevant for \(0< \gamma ^D < 1\). Let us look first at the lower bound. \(\gamma ^D > 0\) iff \(y_p^N + I^T\bar{y} > y_p^D\). From Assumption 5, \(y_v^R > y_v^D\). But, since \(y_v^R = y_p^R\) and \(y_v^D > y_p^D\), it follows that \(y_p^R> y_v^D > y_p^D\). This result along with Assumption 3 imply that \(y_p^N + I^T\bar{y} > y_p^D\), and thus that \(\gamma ^D > 0\).

For the upper bound to be satisfied (i.e., \(\gamma ^D < 1\)), it must be the case that \(y_p^D + I^E\bar{y} > y_p^N\). This is always satisfied since \(y_p^D < y_p^N\) and \(I^E\bar{y} > 0\).

Thus, the thresholds for persuasion to be relevant are also non-binding in the case of peaceful democratization. \(\square\)

Proof of Proposition 8

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Grijalva, D.F. Revolutions of the mind, (threats of) actual revolutions, and institutional change. Public Choice (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-023-01069-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-023-01069-6