Abstract

The study analyzed long-term changes in Japanese crime rates and their relationship with policing and labor market conditions, focusing on the increase in crime rates around 2000. The study used yearly prefectural panel data from 1978 to 2018 and estimated econometric models to explore the factors related to the crime rate. Fixed effects models were used to control for unobservable heterogeneity across prefectures. We addressed the endogeneity problem in the number of police officers with the instrumental variable approach, employing the number of traffic fatalities and the number of firefighters as instruments. Instrumental variable estimation revealed that increasing the number of police officers reduced the crime rate. We also confirmed that crime decreased when the labor market was tight and that increasing minimum wages reduced crime. The model’s variables largely explain crime rate declines since 2002 but do not account for increased crime up to 2002. Policing and labor market conditions do matter in crime rates. In Japan, the number of local police officers increased against the explosion of crime around 2000. Such policing significantly reduced crime after 2002. At the same time, increasing job opportunities and income from legal work also contributed to the decline. In contrast, crime expansion until 2002 was not attributed to the model’s variables, so we need further research.

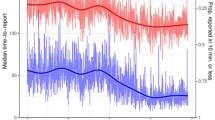

Source: National Police Agency (2019)

Source: National Police Agency (2019)

Source: National Police Agency (2019)

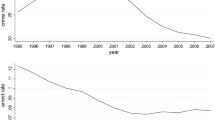

Source: System of Social and Demographic Statistics, the Statistics Bureau of Japan, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications

Source: System of Social and Demographic Statistics, the Statistics Bureau of Japan, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Usually, international comparisons of crime statistics are difficult because the definition and scope of crime vary among countries. Therefore, researchers sometimes use the homicide rate as a proxy for countries’ public safety levels. Data on the homicide rate are considered to be relatively reliable because serious crimes such as homicides are well reported to the police (Archer & Gartner, 1984). In 2018, Japan’s homicide rate was 0.26, whereas it was 4.95, 1.20, and 0.95 in the USA, France, and Germany, respectively. This would partly explain why Japan is considered one of the world’s safest countries. Furthermore, the evidence of Japan’s relative safety is provided by the International Crime Victimization Survey (ICVS), which in 2005, showed that Japan’s victimization rate was 9.9%, the second lowest among Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries after Spain. In particular, robberies and assaults were rare in Japan, but bicycle theft was relatively high. However, the proportion of people feeling unsafe or very unsafe on the street after dark was 35 percent, the third highest among OECD countries.

Theft offenses include larceny on burglary, larceny on vehicle theft, and larceny on non-burglary. Violent offenses include unlawful assembly with dangerous weapons, assault, bodily injury, bodily injury resulting in death, intimidation, and extortion. Felonious offenses include homicide, robbery, arson, and rape. Moral offenses include gambling and indecent offenses.

Notably, the increased number of arrests of elderly persons could be related to the aging of the Japanese population as well as the decrease in morbidity, which has made Japanese elderly persons healthier and more able to commit crimes.

In addition, many police officers would retire near the Tokyo Olympics and Paralympics 2020.

Although there is no theoretical basis for selecting 3-year lags, the results did not differ significantly when the lag period was either reduced or increased.

Although it is more appropriate to use the educational attainment in the population, the data for educational attainment in the population is only available for every 5 years.

We can arbitrarily choose the base year, but we chose 1989 because it was the first year of the Heisei era in the Japanese calendar.

For example, a fine was introduced for theft in 2006. Before that, the only penalty was imprisonment, and first-time offenders were rarely prosecuted. Therefore, fines’ introduction would increase the number of first-time offenders who were sentenced and discourage theft offenses. However, no discontinuous change occurred before and after the fine’s introduction, suggesting that it did not reduce theft.

References

Akiba, H. (1995). Economics of Crime (Hanzai No Keizaigaku). Taga Shuppan.

Archer, D., & Gartner, R. (1984). Violence and Crime in Cross-National Perspective. Yale University Press.

Becker, G. S. (1968). Crime and punishment: an economic approach. The Journal of Political Economy, 76(2), 169–217.

Bradford, B. (2011). Police numbers and crime rates – a rapid evidence review. Her majesty's inspectorate of constabulary. Retrieved September 5, 2023, from https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmicfrs/publications/police-numbers-crime-rates-rapid/

Ehrlich, I. (1973). Participation in illegitimate activities: a theoretical and empirical investigation. The Journal of Political Economy, 81(3), 521–565.

Evans, R. (1977). Changing labor markets and criminal behavior in Japan. The Journal of Asian Studies, 36(3), 477–489.

Hamai, K. (2004). How ‘the Myth of Collapsing Safe Society’ has been created in Japan: Beyond the moral panic and victim industry (Nihon no chian akka shinwa ha ika ni site tsukuraretaka —Chian akka no jittai to haikei youin (moraru panikku wo koete)—). Japanese Journal of Sociological Criminology (Hanzai Shakaigaku Kenkyu), 29, 10–26.

Hamai, K. (2013). Why has the number of crimes reported to the police declined for 10 years in Japan? Is it a real reduction in crime or police artifact? (Naze hanzai ha gensyou siteirunoka.). Japanese Journal of Sociological Criminology (Hanzai Shakaigaku Kenkyuu), 38, 53–77.

Hirschi, T. (2001). Causes of Delinquency (1st ed.). Routledge.

Ishizuka, S. (2017). The irony of criminologists: How to explain the decline in crime? (Hanzaigaakusha No Aironii: Hanzai No Gensho Wo Dou Setumeisuruka?). Annual Bulletin of Research Institute for Social Science (Shakai-Kagaku Nenpou), 47, 57–72.

Kawai, M. (2008). Crime in Japan – understanding the statistics (Nippon No Hanzaijokyo – Toukei Wo Yomitoku). Case Study (Keisu Kenkyu), 295, 29–62.

Lee, Y., Eck, J. E., & Corsaro, N. (2016). Conclusions from the history of research into the effects of police force size on crime—1968 through 2013: a historical systematic review. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 12(3), 431–451.

Levitt, S. D. (1997). Using electoral cycles in police hiring to estimate the effect of police on crime. The American Economic Review, 87(3), 270–290.

Levitt, S. D. (2002). Using electoral cycles in police hiring to estimate the effects of police on crime: reply. The American Economic Review, 92(4), 1244–1250.

Matsueda, R. L. (2013). Rational choice research in criminology: A multi-level framework. In R. Wittek, T. A. B. Snijders, & V. Nee (Eds.), The handbook of rational choice social research (pp. 283–321). Stanford University Press.

McCarthy, B., & Chaudhary, A. R. (2014). Rational choice theory and crime. In G. Bruinsma, & D. Weisburd (Eds.), Encyclopedia of crime and criminal justice. Springer.

Merriman, D. (1991). An economic analysis of the post world war ii decline in the japanese crime rate. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 7(1), 19–39.

Miyoshi, K. (2011). Crime and local labor market opportunities for low-skilled workers: evidence using japanese prefectural panel data. Pacific Economic Review, 16(5), 565–576.

National Police Agency. (2004). White paper on police (Keisatsu Hakusho) 2004. Gyosei.

National Police Agency. (2007). White paper on police (Keisatsu Hakusho) 2007. Gyosei.

National Police Agency. (2015). White paper on police (Keisatsu Hakusho) 2015. Nikkei Insatsu.

National Police Agency. (2017). White paper on police (Keisatsu Hakusho) 2017. Nikkei Insatsu.

National Police Agency. (2019). White paper on police (Keisatsu Hakusho) 2019. Nikkei Insatsu.

National Police Agency. (2021). White paper on police (Keisatsu Hakusho) 2021. Nikkei Insatsu.

Ohtake, F., & Kohara, M. (2010). The relationship between unemployment and crime: evidence from time-series data and prefectural panel data (Shitsugyouritsu To Hanzaihasseiritsu No Kankei: Jikeiretsu Oyobi Todoufuken Paneru nunseki). Japanese Journal of Social Criminology (Hanzai Shakaigaku Kenkyu), 35, 54–71.

Ohtake, F., & Okamura, K. (2000). Juvenile crime and labor market: Time series and prefectural panel data analysis (Shonenhanzai to roudoushijou: Jikeiretsu oyobi todoufuken paneru bunseki). Japanese Economic Research (Nihon Keizai Kenkyu), 40, 40–65.

Okada, K. (2013). Police statistics (Keisatsu Toukei). In K. Hamai (Ed.), Introduction to crime statistics (Hanzai Toukei Nyumon) (pp. 46–74). Nippon Hyoron Sha.

Park, W.-K. (1993a). Changes in crime rate in postwar Japan (1): time-series regression approach (Sengo nihon ni okeru hanzairitsu no suii (1): Jikeiretsu kaiki bunseki apurouchi). Chuo Law Review (Hougaku Shimpo), 99(7–8), 165–230.

Park, W.-K. (1993b). Changes in crime rate in postwar Japan (2): Time-series regression approach (Sengo nihon ni okeru hanzairitsu no suii (2): Jikeiretsu kaiki bunseki apurouchi). Chuo Law Review (Hougaku Shimpo), 99(9–10), 221–266.

Park, W.-K. (1994). Changes in crime rate in postwar Japan (3): time-series regression approach (Sengo nihon ni okeru hanzairitsu no suii (3): Jikeiretsu kaiki bunseki apurouchi). Chuo Law Review (Hougaku Shimpo), 99(11–12), 169–195.

Park, W.-K. (2006). Trends in Crime Rates in Postwar Japan: A Structural Perspective. Shinzansha.

Paternoster, R. (2010). How much do we really know about criminal deterrence. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 100(3), 765–823.

Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. Simon and Schuster.

Rennó Santos, M., Testa, A., Porter, L. C., & Lynch, J. P. (2019). The contribution of age structure to the international homicide decline. PLoS ONE, 14(10), e0222996.

Tsushima, M. (1996). Economic structure and crime: the case of Japan. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 25(4), 497–515.

Yamamura, E. (2009). Formal and informal deterrents of crime In japan: roles of police and social capital revisited. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 38(4), 611–621.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Mototsugu Fukushige (Osaka University), Jun Iritani (Osaka Gakuin University), Mikio Kawai (Toin University of Yokohama), Junya Masuda (Chukyo University), Katsuyohi Nakazawa (Toyo University), and Terukazu Suruga (Kobe University) for constructive comments. All errors are our own.

Funding

This research was financially supported by JSPS Grant-in-Aid for Challenging Research (Pioneering) Grant Number 20K20771, and Scientific Research B Grant Number 18H00802.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Nomura, T., Mori, D. & Takeda, Y. Policing, Labor Market, and Crime in Japan: Evidence from Prefectural Panel Data. Asian J Criminol 18, 297–326 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-023-09403-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-023-09403-z