Abstract

This paper offers a compositional analysis of Mandarin universal wh’s in construction with an additive/scalar adverb ye ‘also/even’. In the analysis, universal force is derived from exhaustification of the subdomain alternatives activated by wh-items under stress, and the tendency of wh-ye to appear in negative sentences is explained by the interaction between ye and domain widening. Specifically, the ye in wh-ye is argued to be a scalar ye imposing a total order presupposition on its associated set of alternatives. In wh-ye it associates with the domain argument of the wh, and the requirement can be met by either an ordered wh or a two-point scale \(\langle D',D \rangle \) made available through domain widening, specifically by widening of QUDs. The negative preference follows from the fact that a QUD is most naturally widened when it is settled negatively, as in the case of negatively biased questions with minimizers/maximizers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

# marks the infelicity of ye under the relevant readings. Of course, an additive or scalar interpretation of ye would be fine in (2).

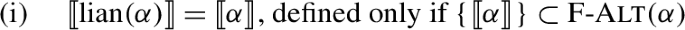

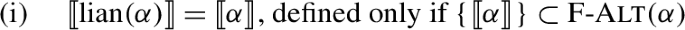

Consider the following entry for lian from Xiang (2020, ex. (80)), which states that lian indicates the presence of focus within its argument, without making any semantic contribution.

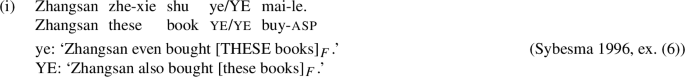

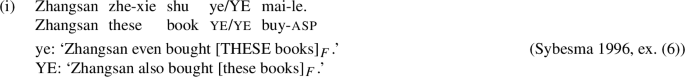

A reviewer reports their judgment that ye without lian (e.g., (10a)) can only have an additive reading, and suggests that lian, rather than ye, contributes scalarity. We do not share this judgment. To our consultants, lian is not necessary for ye to express a scalar meaning. Indeed, examples of ye conveying scalarity without lian are easy to find (e.g., Ernst and Wang 1995, p. 235; Hole 2004, p. 25; Liao 2011, p. 257; Yang 2020, p. 101), and acknowledged in the typological literature (e.g., Forker 2016, p. 73). We further add the following observation from Sybesma (1996), who remarks that “like dou, ye, when used as a focalizer, is unstressed; it can be stressed, in which case it means ‘also’ .” As is clear from Sybesma’s example in (i), focalizer-ye is just ye used as even, and ye without lian can convey scalarity. Exactly the same observation is made in Hole (2004, p. 25): in the case of lian without ye, “emphatic stress on the foci will yield the even-readings, otherwise, we get also-readings.” We find the generalization empirically correct; that is, when lian is absent, ye is ambiguous between also and even and stress disambiguates. This might explain why the reviewer finds it hard or even impossible to construe ye as even without lian, if we assume lian, as a special focus marker, can be used to disambiguate and unequivocalness is preferred.

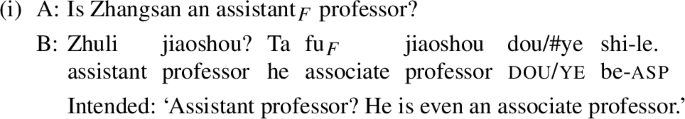

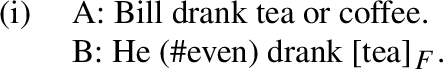

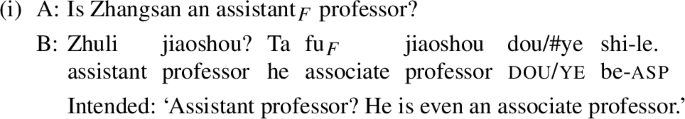

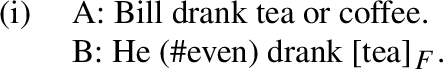

A reviewer offers another interesting example where scalar-dou and ye differ:

The reviewer claims that (i) with ye is unacceptable because this is a scalar context, and ye, unlike dou, is not scalar without lian (see the same reviewer’s comment in fn. 4). We however find an explanation based on additivity more plausible, noting that (i) was initially used in Rullmann (1997) as evidence that even does not encode additivity, as the alternatives here are mutually exclusive. We propose that this feature of the alternatives, combined with the conclusion drawn from (11) that only scalar-ye has an additive component, explains the contrast in (i). We offer two pieces of evidence for such an explanation. First, adding lian to ye in (iB) does not improve the sentence, showing that scalarity (assuming with the reviewer that lian-ye is always scalar) is not the issue. Second, adding negation saves the sentence: Ta (lian) FUF jiaoshou ye bu shi ‘he is not even an associate professor.’ This is fully expected under the present view, as negation, without rendering the context non-scalar, makes the alternatives compatible.

See Xiang (2020) for the proposal that Mandarin minimizers like the one in (10b) undergo focus-reconstruction and get interpreted below negation.

An operator F is nonveridical iff, for any p, F(p) does not entail p. Please refer to Giannakidou (1998) and related literature for a framework that uses nonveridicality to explain polarity and free choice items.

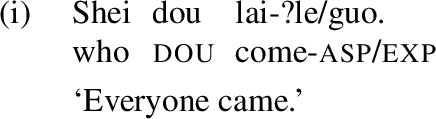

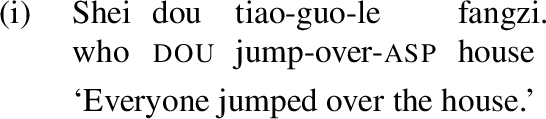

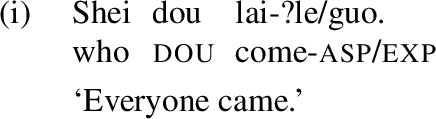

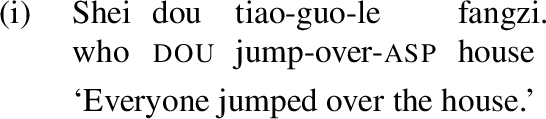

A reviewer, based on Xiang’s (2020) claim that (i) with the perfective marker le is less natural than with experiential guo, suggests that the acceptability of wh-dou in positive episodic sentences may vary among speakers. While we acknowledge that positive episodic wh-dou’s may have special pragmatic requirements, we do not find them to be unacceptable. For instance, all of our consultants accept (i) with le as an answer to the question shei lai-le? “who came?” Our empirical standpoint also aligns with previous research, such as Giannakidou and Cheng (2006, p. 137), Liao (2011, p. 97) and Chen (2018, §2). Moreover, sentences with episodic positive wh-dou are often used as experimental items to assess children’s comprehension of universal wh’s, accompanied by pictures describing episodic events (e.g., Zhou 2015, ex. (25) as shown in (ii) and Yang et al. 2022, ex. (19)). These sentences are consistently accepted as ∀-statements by both children and adults. Lastly, the reviewer suggests examining corpus data to pinpoint the exact contextual requirements of positive episodic wh-dou, which we plan to investigate in future work.

Two clarifications are needed. First, the marker buguan in (24a), likewise wulun, is usually glossed as ‘no matter’. These markers can optionally attach to universal wh’s and to antecedents of unconditionals, referred to as nominal and clausal-wulun, respectively, in Lin (1996). Second, speakers may have varying judgments about (24) and positive wh-ye in general. The variation is discussed below.

Specifically, we first searched for “duoshao $4 ye”, which looks for tokens with ≤4 characters between duoshao and ye. This query yielded 1,182 results. We then added the condition “ye–6(bu∣mei∣wu∣bie∣ xiu∣nan∣mo∣beng∣wei)”, requiring that there be no negation of any kind after ye within the next 6 characters. This returned 463 occurrences. See http://ccl.pku.edu.cn:8080/ccl_corpus for the CCL corpus.

There are three maximal subsets of \(\left \{a\wedge \neg b, b\wedge \neg a, a\wedge b \right \} \) that can be jointly negated with a∨b being true: \(\left \{a\wedge \neg b, a\wedge b \right \} \), \(\left \{b\wedge \neg a, a\wedge b \right \} \), and \(\left \{a\wedge \neg b, b\wedge \neg a \right \} \). Their intersection is ∅, and thus there is no innocently excludable alternative. See also Chierchia (2013, pp. 120-122).

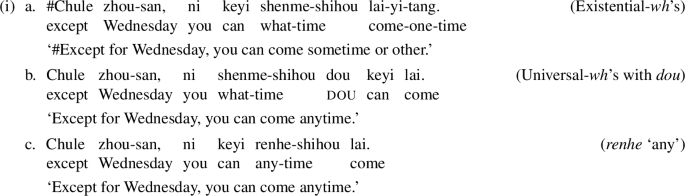

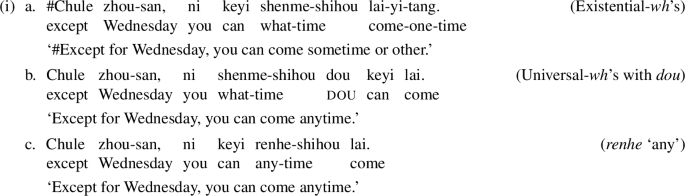

To address a concern raised by a reviewer regarding the claim that existential-wh’s trigger partial modal inferences, we offer (i) involving Mandarin exceptive chule to sharpen the intuition. Assuming that exceptives are sensitive to some sort of ∀-quantification, the contrast between (ia) and (ib-c) shows that existential-wh’s, unlike universal-wh’s and universal FCI renhe ‘any’, do not convey free choice of the universal variation type. See Giannakidou (2018, §5) for additional evidence that Mandarin existential wh’s are not “exhaustive”.

One way to guarantee that only subdomain alternatives are triggered, as proposed for any in Jeong and Roelofsen (2022), is to assume that the domain argument of the wh that receives focus is the set \(D_{e}\) of all entities, and contextual restriction happens when \(D_{e}\) is intersected with \(D^{c}\), the set of things relevant in c. Under this treatment, \([\!\![{\text{shei}_{D}}_{e} ]\!\!]^{c} = \lambda P\exists x\in D_{e} \cap D^{c} [\text{person}(x)\wedge P(x)]\), and focus on \(D_{e}\) will deliver all and only subdomain alternatives.

We can also use indexed foci (Wold 1996) to regulate associations, as in (i). We prefer (44b) using movement however, as there is indeed overt movement of the wh to the left of ye (see, e.g., (17) and (39a)).

That is, if p entails q, then p is also less likely than q, unless p and q are contextually equivalent (see, e.g., Crnič 2019b,c). This means that the scalar presupposition is satisfied in any context where the prejacent is not contextually equivalent with its alternatives. The latter requirement is easy to satisfy in normal contexts.

There is a syntactic difference: the focus in (49) appears to ye’s right while in (50) to its left. This does not affect the point under discussion, as moving the focus in (49) to ye’s left does not save the sentence.

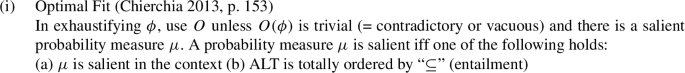

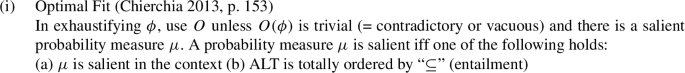

A total order is a partial order in which any two elements are comparable. We suspect that this may be a requirement for other even-like particles, as similar puzzles have been observed for English even, as shown in (i) from Greenberg (2016, ex. (20)). Greenberg considers several accounts of (i), but finds them inadequate and uses (i) as evidence against the standard likelihood-based semantics of even. It remains to be seen whether total order can offer a new perspective. Interestingly, total order has also been used by Chierchia (2013) to regulate the choice between O(nly)-exhaustification and E(ven)-exhaustification, as shown in his Optimal Fit in (ii) (with O being our exh). Thus, total order, according to Chierchia, also plays a role in the felicitous use of covert even.

In (51a) we assume that the individual conjuncts are alternatives to the conjunction. This is a standard assumption as they are simply the domain alternatives of the conjunction (Chierchia 2013, p. 138).

Assume that there are exactly three persons a, b and c in the model. The prejacent in (57c) is equivalent to ¬speak(a)∧¬speak(b)∧¬speak(c), and its set of subdomain alternatives in (57d) is {¬spk(a),¬spk(b),¬spk(c),¬spk(a)∧¬spk(b),¬spk(a)∧¬spk(c),¬spk(b)∧¬spk(c),¬spk(a)∧¬spk(b)∧¬spk(c)}. The set is obviously not totally ordered.

See also Fălăuş and Nicolae (2022) for using domain widening to explain the presence of an additive particle in a class of Romanian free choice items.

Clemens Mayr (NLS editor) points out correctly that the proposed negative bias also conflicts with ye’s additive presupposition, which requires everyone in \(D'\) to be speaking, and wonders whether the additive presupposition might actually prevent the emergence of the negative bias in the first place. We suggest that the negative bias is a calculable obligatory implicature (potentially a manner implicature due to the speaker’s act of widening the QUD), and its conflict with the meaning of the wh-ye sentence, whether in terms of its assertion or presupposition, would result in deviance. Furthermore, several recent proposals (e.g., Szabolcsi 2017, Fălăuş and Nicolae 2022) argue that the standard additive presupposition of (scalar) additives is not inherent to the particles but derived from obligatory exhaustification. From this perspective, the conflict between the negative bias and the additive “presupposition” can been seen as a clash of implicatures. We appreciate the editor’s valuable comment, and hope to study the precise nature of the negative bias and the additive presupposition in future work.

There are other options. For instance, the alternative set could be built below and without negation, as Rooth (1996, §5.1) and Beaver and Clark (2008, §3.2) propose for the “focus sensitive” negation in (66). A Roothian LF for (66b) under this treatment would be [neg [IF took your car]\(\sim _{C}\)], with the focus evaluated below ¬. Rooth’s solution is not adopted for wh-ye because it requires negation to scope over the focus, but as we saw in Section 3.1, there are cases of negative wh-ye where negation cannot scope over the wh. Alternatively, we could adopt the structure-based theory of alternatives in Fox and Katzir (2011), where positive alternatives without negation are deletion-alternatives. It is worth noting that under both of these accounts, positive sentences do not readily activate negative alternatives, in line with the treatment assumed in the main text.

It is worth highlighting the fact that enriching the alternative semantic value of ye’s prejacent need not affect the value of \(C'\), the actual input for ye, since \(C'\) is only required to be a subset of the former.

While our consultants all agree there is a contrast between (68a) and (68b), some find it not as sharp as Zhang (2021) claimed. Specifically, some speakers indicate that (68a) is not entirely unacceptable, while a few judge (68b) less natural. We hypothesize that the variation may be attributed to the varying levels of ease or difficulty among speakers in accommodating negative QUDs for positive wh-ye sentences.

Further research is needed to investigate the possibility of positive sentences with negative QUDs and their specific contextual requirements. If it turns out that (67) (i.e., IF passed) involves a negative QUD, as suggested by Clemens Mayr, and ordinary question-answer pairs are not constrained by the Focus Principle as stated in (64), we can still maintain the current analysis, by directly building a version of (64) into the semantics of ye. Specifically, we can add into the lexical entry of ye an additional requirement stating that \([\!\![\mathit{ye}_{C} S ]\!\!]^{g}\) is defined only if QUD \(\subseteq [\!\![S ]\!\!]_{\mathrm{alt}}\). By doing so, we can preserve the asymmetry predicted by the Focus Principle solely for wh-ye sentences.

References

Alonso-Ovalle, Luis, and Paula Menéndez-Benito. 2010. Modal indefinites. Natural Language Semantics 18(1): 1–31.

Ba, Dan, and Yi-sheng Zhang. 2012. Differences between “dou (all)” and “ye (also)” in free choice sentences. Journal of Guangxi Normal University 48(4): 69–74.

Bar-Lev, Moshe E. 2021. An implicature account of homogeneity and non-maximality. Linguistics and Philosophy 44: 1045–1097.

Beaver, David I., and Brady Z. Clark. 2008. Sense and sensitivity: How focus determines meaning. New York: Wiley-Blackwell.

Beck, Sigrid, and Hotze Rullmann. 1999. A flexible approach to exhaustivity in questions. Natural Language Semantics 7(3): 249–298.

Biq, Yung-O. 1989. Ye as manifested on three discourse planes: Polysemy or abstraction. In Functionalism and Chinese grammar, eds. J. H.-Y. Tai and F. F. S. Hsueh, 1–18. South Orange: Chinese Language Teachers Association.

Bowler, M. 2014. Conjunction and disjunction in a language without ‘and’. In Semantics and linguistic theory (SALT) 24, eds. Todd Snider, Sarah D’Antonio, and Mia Weigand. 137–155.

Büring, Daniel. 2003. On d-trees, beans, and b-accents. Linguistics and Philosophy 26(5): 511–545.

Chao, Yuen Ren. 1968. A grammar of spoken Chinese. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Chen, Liping. 2008. Dou: Distributivity and beyond, PhD dissertation, Rutgers University.

Chen, Li. 2018. Downward entailing and Chinese polarity items. Milton Park: Routledge.

Chen, Zhuo. 2021. The non-uniformity of Chinese wh-indefinites through the lens of algebraic structure, PhD dissertation, City University of New, York.

Cheng, Lisa Lai-Shen. 1995. On dou-quantification. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 4(3): 197–234.

Cheng, Lisa Lai-Shen. 2009. On every type of quantificational expression in Chinese. In Quantification, definiteness, and nominalization, eds. M. Rather and A. Giannakidou, 53–75. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chierchia, Gennaro. 2013. Logic in grammar. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chierchia, Gennaro, Danny Fox, and Benjamin Spector. 2011. Scalar implicature as a grammatical phenomenon. In Semantics: An international handbook of natural language meaning, eds. K. von Heusinger, C. Maienborn, and P. Portner. Vol. 3, 2297–2331. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Chierchia, G., and H.-C. Liao. 2015. Where do Chinese wh-items fit? In Epistemic indefinites: Exploring modality beyond the verbal domain, eds. Luis Alonso-Ovalle and Paula Menéndez-Benito, 30–59. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199665297.003.0002.

Crnič, Luka. 2017. Free choice under ellipsis. The Linguistic Review 34: 249–294.

Crnič, Luka. 2019a. Any, alternatives, and pruning. Unpublished manuscript.

Crnič, Luka. 2019b. Any: Logic, likelihood, and context (pt. 1). Language and Linguistics Compass 13(11). https://doi.org/10.1111/lnc3.12354.

Crnič, Luka. 2019c. Any: Logic, likelihood, and context (pt. 2). Language and Linguistics Compass 13(11). https://doi.org/10.1111/lnc3.12353.

Dayal, Veneeta. 1998. Any as inherently modal. Linguistics and Philosophy 21: 433–476.

Dayal, Veneeta. 2013. A viability constraint on alternatives for free choice. In Alternatives in semantics, London: Palgrave Macmillan.

den Dikken, Marcel, and Anastasia Giannakidou. 2002. From hell to polarity: “Aggressively non-d-linked” wh-phrases as polarity items. Linguistic Inquiry 33(1): 31–61. https://doi.org/10.1162/002438902317382170.

Dong, Hongyuan. 2009. Issues in the semantics of Mandarin questions, PhD dissertation, Cornell University.

Eckardt, Regine, and Qi Yu. 2020. German bloss-questions as extreme ignorance questions. Linguistica Brunensia 68(1): 7–22. https://doi.org/10.5817/LB2020-1-2.

Ernst, Thomas, and Chengchi Wang. 1995. Object preposing in Mandarin Chinese. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 4(3): 235–260. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01731510.

Fălăuş, Anamaria, and Andreea C. Nicolae. 2022. Additive free choice items. Natural Language Semantics 30: 185–214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-022-09192-8.

Forker, Diana. 2016. Toward a typology for additive markers. Lingua 180: 69–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2016.03.008.

Fox, Danny. 2007. Free choice and the theory of scalar implicatures. In Presupposition and implicature in compositional semantics, eds. U. Sauerland and P. Stateva, 71–120. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Fox, Danny, and Roni Katzir. 2011. On the characterization of alternatives. Natural Language Semantics 19: 87–107. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-010-9065-3.

Giannakidou, Anastasia. 1998. Polarity sensitivity as (non)veridical dependency. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Giannakidou, Anastasia. 2018. A critical assessment of exhaustivity for negative polarity items: The view from Greek, Korean, Mandarin and English. Acta Linguistica Academica 65(4): 503–545. https://doi.org/10.1556/2062.2018.65.4.1.

Giannakidou, Anastasia, and Lisa Lai-Shen Cheng. 2006. (In)definiteness, polarity, and the role of wh-morphology in free choice. Journal of Semantics 23(2): 135–183.

Greenberg, Yael. 2016. A novel problem for the likelihood-based semantics of even. Semantics and Pragmatics 9(2): 1–28. https://doi.org/10.3765/sp.9.2.

Guo, R. 1998. Valency of “one person ye/dou not come”. In Study on valency grammar of modern Mandarin, eds. Y. Shen and D. Zheng Bejing. Vol. 2. Bejing: Peking University Press.

Haspelmath, Martin. 1997. Indefinite pronouns. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hengeveld, Kees, Sabine Iatridou, and Floris Roelofsen. 2021. Quexistentials and focus. Linguistic Inquiry 54(3): 571–624.

Hole, Daniel. 2004. Focus and background marking in Mandarin Chinese. London: Routledge.

Iatridou, Sabine, and Hedde Zeijlstra. 2021. The complex beauty of boundary adverbials: In years and until. Linguistic Inquiry 52: 89–142.

Jackendoff, Ray S. 1972. Semantic interpretation in generative grammar. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Jasinskaja, Katja, and Henk Zeevat. 2009. Explaining conjunction systems: Russian, English, German. In Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung 13, eds. Arndt Riester, and Torgrim Solstad, 231–256.

Jeong, Sunwoo, and Floris Roelofsen. 2022. Focused NPIs in statements and questions. Journal of Semantics 40(1): 1–68. https://doi.org/10.1093/jos/ffac014.

Kadmon, Nirit, and Fred Landman. 1993. Any. Linguistics and Philosophy 16(4): 353–422. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00985272.

Karttunen, Lauri. 1977. Syntax and semantics of questions. Linguistics and Philosophy 1(1): 3–44.

Karttunen, Lauri, and Stanley Peters. 1979. Conventional implicature. In Syntax and semantics 11: Presupposition, 1–56. New York: Academic Press.

König, Ekkehard. 1991. The meaning of focus particles: A comparative perspective. London: Routledge.

Kratzer, Angelika, and Junko Shimoyama. 2002. Indeterminate pronouns: The view from Japanese. In 3rd Tokyo conference on psycholinguistics, ed. Yukio Otsu, 1–25. Tokyo: Hituzi Syobo.

Krifka, Manfred. 1992. A compositional semantics for multiple focus constructions. In Informationsstruktur und Gammatik, Linguistische Berichte Sonderhefte, ed. J. Jacobs. Vol. 4, 17–53. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Krifka, Manfred. 1995. The semantics and pragmatics of polarity items. Linguistic Analysis 25: 209–257.

Kripke, Saul A. 2009. Presupposition and anaphora: Remarks on the formulation of the projection problem. Linguistic Inquiry 40(3): 367–386.

Lee, Thomas Hun-Tak. 1986. Studies on quantification in Chinese, PhD dissertation, UCLA.

Li, Yen-Hui Audrey. 1992. Indefinite wh in Mandarin Chinese. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 1(2): 125–155. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00130234.

Liao, Hsiu-Chen. 2011. Alternatives and exhaustification: Non-interrogative uses of Chinese wh-words, PhD dissertation, Harvard University.

Lin, J.-W. 1996. Polarity licensing and wh-phrase quantification in Chinese, PhD dissertation, University of Massachusetts.

Lin, Jo-wang. 1998. On existential polarity-wh-phrases in Chinese. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 7: 219–255. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008284513325.

Liu, Mingming. 2017. Varieties of alternatives: Mandarin focus particles. Linguistics and Philosophy 40(1): 61–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-016-9199-y.

Liu, Mingming. 2019. Unifying universal and existential wh’s in Mandarin. In Proceedings of Semantics and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 29, eds. Katherine Blake, Forrest Davis, Kaelyn Lamp, and Joseph Rhyne, 258–278.

Liu, Mingming, and Yu-an Yang. 2021. Modal wh-indefinites in Mandarin. In Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung 25, eds. Patrick Georg Grosz et al., 581–599. https://doi.org/10.18148/sub/2021.v25i0.955.

Lu, J. 1986. Universal subjects and other issues. Studies of the Chinese Language 3: 161–167.

Ma, Z. 1982. On “ye”. Studies of The Chinese Language 2.

Roberts, Craige. 2012. Information structure in discourse: Towards an integrated formal theory of pragmatics. Semantics and Pragmatics 5(6): 1–69.

Rooth, Mats. 1992. A theory of focus interpretation. Natural Language Semantics 1: 75–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02342617.

Rooth, Mats. 1996. Focus. In The handbook of contemporary semantic theory, 271–298. Oxford: Blackwell.

Rullmann, Hotze. 1997. Even, polarity, and scope. In Papers in experimental and theoretical linguistics, Vol. 4, 40–64.

Sauerland, Uli. 2004. Scalar implicatures in complex sentences. Linguistics and Philosophy 27: 367–391.

Shyu, Shu-ing. 1995. The syntax of focus and topic in Mandarin Chinese, PhD dissertation, University of Southern California.

Singh, Raj, Ken Wexler, Andrea Astle-Rahim, Deepthi Kamawar, and Danny Fox. 2016. Children interpret disjunction as conjunction: Consequences for theories of implicature and child development. Natural Language Semantics 24(4): 305–352. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-016-9126-3.

Sugimura, H. 1992. Semantic analysis of ‘wh + ye/dou …’ in modern Chinese. Chinese Teaching in the World 21(3): 166–172.

Sybesma, Rint. 1996. Review of the syntax of focus and topic in Mandarin Chinese by Shu-ing Shyu. Glot International 2: 13–14.

Szabolcsi, Anna. 2015. What do quantifier particles do? Linguistics and Philosophy 38(2): 159–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-015-9166-z.

Szabolcsi, Anna. 2017. Additive presuppositions are derived through activating focus alternatives. In Proceedings of the 21st Amsterdam colloquium, eds. A. Cremers, T. van Gessel, and F. Roelofsen, 455–464.

Szabolcsi, Anna, and Frans Zwarts. 1993. Weak islands and an algebraic semantics for scope taking. Natural Language Semantics 1(3): 235–284. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00263545.

Tovena, Lucia M. 2006. Dealing with alternatives. In Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung, eds. Christian Ebert and Cornelia Endriss. Vol. 10, 373–388. https://doi.org/10.18148/sub/2006.v10i2.739.

van Rooij, Robert. 2003. Negative polarity items in questions: Strength as relevance. Journal of Semantics 20(3): 239–273. https://doi.org/10.1093/jos/20.3.239.

Wei, Wei. 2020. Discourse particles in Mandarin Chinese, PhD dissertation, University of Southern California.

Wold, Dag E. 1996. Long distance selective binding: The case of focus. In Semantics and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 6, eds. Teresa Galloway and Justin Spence. 311–328.

Xiang, Yimei. 2020. Function alternations of the Mandarin particle Dou: Distributor, free choice licensor, and ‘even’. Journal of Semantics 37(2): 171–217. https://doi.org/10.1093/jos/ffz018.

Xie, Zhiguo. 2007. Nonveridicality and existential polarity wh-phrases in Mandarin. In Proceedings from the 43 annual meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society, 121–135.

Yang, K. 2002. The positive/negative distribution of [wh-words + ye/dou + P]. In New exploration of study on Chinese grammar 1, Hangzhou: Zhejiang Education Publishing House.

Yang, Yang, Stella Gryllia, and Lisa Lai-Shen Cheng. 2020. Wh-question or wh-declarative? Prosody makes the difference. Speech Communication 118: 21–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.specom.2020.02.002.

Yang, Yu-an, Daniel Goodhue, Valentine Hacquard, and Jeffrey Lidz. 2022. Do children know whanything? 3-year-olds understand the ambiguity of wh-phrases in Mandarin. Language Acquisition 29(3): 296–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/10489223.2021.2020275.

Yang, Zhaole. 2019. Mandarin Yě and scalarity. Studies in Chinese Linguistics 39(2): 155–178. https://doi.org/10.2478/scl-2018-0006.

Yang, Zhaole. 2020. Yě, yě, yě: On the syntax and semantics of Mandarin yě, PhD dissertation, Leiden University.

Yuan, Y. 2004. The semantic contribution of ‘dou’ and ‘ye’ in the construction ‘wh + dou/ye + vp’. Linguistic Sciences 3(5): 3–14.

Zanuttini, Raffaella, and Paul Portner. 2003. Exclamative clauses: At the syntax-semantics interface. Language 79(1): 39–81. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2003.0105.

Zhang, X. 2021. A study on the Universal Subject Sentences of “interrogative pronoun” in modern Chinese, PhD dissertation, Jilin University.

Zhou, Peng. 2015. Children’s knowledge of wh-quantification in Mandarin Chinese. Applied Psycholinguistics 36(2): 411–435. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716413000283.

Zhu, D. 1982. Lecture notes on grammar. Shanghai: The Commercial Press.

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to the editor Clemens Mayr and the anonymous reviewers for their invaluable feedback and guidance, which greatly improved the paper. I also thank Yanyan Cui, Xiaolei Fan, Daniel Hole, Fengkui Ju, Shumian Ye, Linmin Zhang, and Sha Zhu for their valuable comments and suggestions. Support from the grant (22&ZD295) of the National Social Science Fund of China is acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The author declares that he has no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, M. Additivity, scalarity and Mandarin Universal wh’s. Nat Lang Semantics 31, 179–218 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-023-09207-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-023-09207-y