Abstract

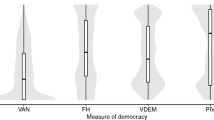

We use comparative constitutions project (CCP) data to explore whether Constitutions that follow revolutions are designed differently. We employ matching methods using 36 treatments (revolutionary Constitutions) and 162 control units (new Constitutional adoptions without a revolution). We find some evidence that revolutionary Constitutions are less rigid (i.e., their procedural barriers to amendment are weaker). Otherwise, revolutionary Constitutions seem similar to non-revolutionary ones. However, we do find strong evidence that revolutionary Constitutions are associated with a greater likelihood of ex post democracy. The results (less rigid, higher likelihood of democracy) hold for those not associated with ending colonial rule or the fall of the USSR. The greater ex post democracy result is reported for various democracy measures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The quote comes from the online “DATA DESCRIPTION” of Beissinger’s “Revolutionary Episodes Dataset” (Revolutionary episodes dataset_v_1.0.zip (dropbox.com)), which we use in this paper.

We will use the “big-C” form of “Constitution” do denote a de jure (written; codified) form (as opposed to a purely de facto constitution. The little-c-vs.-big-C distinction is utilized in political science, constitutional law, as well as economics (e.g., Brennan & Pardo 1991, Harris 1993, Michelman 1998, Elkins and Ginsberg 2021).

The CCP index for rigidity will be described below in Sect. 3.

As simple example, consider the fact that revolutionary Constitutions are, on average, longer than their predecessors. Country-level Constitutions have, on average, been becoming longer over time (Versteeg and Zackin). Since revolutionary Constitutions are being compared to those that came before them, the difference in unconditional means may simply reflect that secular trend.

Furthermore, the vast majority of countries have enacted a constitution. At its most basic level, they spend time drafting and changing them, presumably because they view them as valuable in some capacity.

Even today—and 17 amendments later—the US Constitution is only 7,591 words.

In a related argument, Bjørnskov and Voigt (2014) argue that societies with lower social trust are likely to insist on Constitutions that cover a larger number of contingencies. They report evidence cross-country evidence consistent with their hypothesis.

Tsebelis and Nardi (2016) and Tsebelis (2017) present cross-country evidence supporting their hypothesized correlations. However, Bologna Pavlik et al. (2023) employ synthetic control methods to cases where countries adopted new Constitutions that were significantly longer than their predecessors. They finding no clear evidence that causation runs from greater length to greater corruption.

And there is a sizeable minority (just under 20 percent) of cases where the Constitution has no preamble (Elkins and Ginsburg 2021, p. 333). Ginsburg (2010a, p. 71) notes that “socialist countries tend to devote more attention to the preamble than to the description of government organs or the promulgation of rights: of the fifteen constitutions in our sample that have preambles of more than 1000 words, five are socialist and another (Iran) is a highly ideological constitution”.

The empirical literature on Constitutional rights vis-à-vis economic and policy outcomes is scant. Early on, de Vanssay and Spindler (1994) consider various negative and positive (“social”) rights in a cross-section of 100 countries. The only statistical significant correlation with income-per capita is for a “Bill of Rights” dummy, and it is negative. Ben-Bassat and Dahan (2008) report that the extent of social rights does not significantly correlate with public policy. Relatedly, Chilton and Versteeg (2017) report that rights to health care and education are not significantly related to government spending in those areas.

There are few empirical studies of Constitutional rigidity in relation to economic outcomes. Callais and Young (2022) report some evidence linking greater rigidity to lower economic growth across countries. Alternatively, Callais and Young (2021) report some evidence of a negative link between rigidity and different areas of economic freedom (such as a stricter regulatory environment and worsening property rights protections); economic freedom is itself associated with higher incomes and growth: see Hall and Lawson 2014. Speaking to credible commitments, Dove and Young (2019) study nineteenth century US states and find that greater rigidity in their Constitutions was associated with less likelihood of default on public debt.

Vahabi et al. (2020) given an excellent overview of the conceptualizations of “revolution” by different social scientists over time. Relative to the distinction emphasized here, Samuel Huntington (1968) made a very different one: “Western” versus “Eastern.” In the former case (e.g., France in 1789; Russia in 1917), an absolute monarchy rooted in traditional society is exposed and overthrown during a crisis precipitated by modernizing forces; in the latter case (e.g., China in 1949; Vietnam in 1945), a modernizing regime—such as a dictatorship or colonial government—is overthrown. (Huntington associates greater and more sustained violence with Eastern-type revolutions.).

From the Beissinger codebook, p. 5.: https://www.dropbox.com/s/7zutziehohxn4g1/Revolutionary%20episodes%20dataset_v_1.0.zip?dl=0&file_subpath=%2FData+description.pdf.

We will provide details on the coding of Beissinger’s dataset in relation to this conceptualization.

Up through the eighteenth century, a written Constitution was by no means a sine qua non for a nation state. (Of those that came into existence before the nineteenth century, half of them went over 300 years without a Constitutional document.) That has decidedly changed: 85 percent of nation states that have formed since had a Constitution by their second year of existence; nearly 95 percent by their fifth year (Elkins et al., 2009, pp. 41–43). De jure/written Constitutions are now (by very far) the rule.

In the case of France, this was at very least true for over two decades (or more, depending on whether one views the 1814 Bourbon Restoration as a true return of the incumbent regime, which is shaky given the constitutional nature of that monarchy).

Federalist 48. See Hardin (1999) for views on why the coordination model makes Constitutions mattering intelligible; also—less convincingly in the authors’ views—why a “contract” view might also be compelling.

More detail is provided in Sect. 8.

More formally, we use a treatment indicator for which we assign a value of 1 (yes, a revolution occurred) or 0 (no, one did not). Then we assume there is an expectation for an outcome (the subsequent change in Constitutional design) conditional on the indicator being 1 (rather than 0), as well as other variables (the covariates).

Differencing the dependent variable in regression analysis removes between-country variation and, therefore, utilizes within-country variation exclusively. However, in the present context, the within-country variation is what we want to focus on. Revolutions are singular events; cross-country comparison of revolutions versus non-revolution outcomes is sensible. Also matching methods and regression analysis are different in an important way. Matching methods compare treated and non-treated countries, conditional on pre-treatment covariate values: this takes into account within-country variation implicitly: matching is based on covariates during the pre-treatment period (including covariate variation over that time) and then comparing post-treatment changes.

Notwithstanding the above, as a robustness check we do report DID results in Sect. 7 below.

For example, Bologna Pavlik et al. (2023) employ SCM to five cases where a country adopted a substantially ( 50%) longer Constitution to see whether there is an effect on corruption. The results are mixed. One of the cases where a significant increase in corruption is reported is Venezuela in 1999. However, the SCM result is ultimately based on that particular case, it is difficult to distinguish between the effect of a longer Constitution and the sort of (Hugo) “Chavez effect” reported by Grier and Maynard (2016).

These were supplemented by “135 other occasional sources (newspapers, websites, and online encyclopedias) and over eight hundred scholarly books and articles” to provide information on specific episodes (codebook, p. 12).

For example, the New People’s Army Communist Revolution in the Philippines has been considered “ongoing” since 1969. As such, any constitutional change during this time period would not be considered a treatment since its success has yet to be determined. However, the Republic of Congo Civil War that started in 1997 and was considered “successful” by 1999 is coded as a possible treatment. (In this specific case, it is a treatment since a new constitution was put in place in 2001).

The treatments in Table 1 are those that can, given other data constraints, be used in any single estimation. Only our measure of de facto democracy is based on all 36 of those treatments. (Each of our benchmark estimations on constitutional characteristics in Tables 5, 6, 7 below are based on a number of treatments between 16 and 21.).

Note that a Constitution’s rigidity is not calculated based on its own amendment rate; rather, the amendment rates of all Constitutions in the sample are together used to estimate the weights placed on procedural variables.

For control units, the pre-treatment score is the democracy score the year before the new Constitution. Note that if, after initial gains, there is democratic “backsliding” over the 5-year period, then a country is coded as having no change in its democracy score.

Since Freedom House data is only available from 1973 onward, including it in our baseline results would cut 23 years of potential treatments and matches. The Freedom House data can be downloaded at: https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world.

In making statements such as these, we are taking ATET estimates relative to the standard deviations reported for lagged outcome levels (Table 3; Panel b).

The conceptual overlap between these indices is large. However, they are distinct in what they emphasize. For example, “the liberal principle of democracy emphasizes the importance of protecting individual and minority rights against the tyranny of the state and the tyranny of the majority” while, alternatively, “[e]galitarian democracy is achieved when 1 rights and freedoms of individuals are protected equally across all social groups; and 2 resources are distributed equally across all social groups; 3 groups and individuals enjoy equal access to power” (Coppedge et al., 2021, pp. 44–45).

We also ran DID estimations for each of the five V-Dem measures. The estimated effect of a revolutionary Constitution was positive and statistically significant (5% level or better) in each case. (Results available upon request).

References

Acemoglu, D., Naidu, S., Restrepo, P., & Robinson, J. A. (2019). Democracy does cause growth. Journal of Political Economy, 127(1), 47–100.

Ackerman, B. (2019). Revolutionary constitutions: Charismatic leadership and the rule of law. Harvard University Press.

Ackerman, B. (2015). Three paths to constitutionalism – and the crisis of the European Union. British Journal of Political Science, 45(4), 705–714.

Ackerman, B. (1991). We the People: foundations. Harvard University Press.

Aghion, P., & Bolton, P. (2003). Incomplete social contracts. Journal of the European EconomicAssociation, 1(1), 38–67.

Albert, R. (Ed.). (2020). Revolutionary constitutionalism. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Alvarez, M., Cheibub, J. A., Limongi, F., & Przeworski, A. (1996). Classifying political regimes. StudiesIn Comparative International Development, 31(2), 3–36.

Aranson, P. H. (1987). Procedural and substantive constitutional protection of economic liberties. Cato Journal, 7(2), 345–375.

Arban, E., & Samararatne, D. (2022). What’s constitutional about revolutions? Oxford Journal of LegalStudies, 42(2), 680–701.

Arendt, H. (1963). On revolution. Penguin Books.

Barro, R. J. (1996). Democracy and growth. Journal of Economic Growth, 1(1), 1–27.

Barzel, Y. (1989). Economic analysis of property rights. Cambridge University Press.

Beissinger, M. R. (2022). The revolutionary city: Urbanization and the global transformation of rebellion. Princeton University Press.

Ben-Bassat, A., & Dahan, M. (2008). Social rights in the constitution and in practice. Journal ofComparative Economics, 36(1), 103–119.

Bjørnskov, C., & Rode, M. (2020). Regime types and regime change: A new dataset on democracy, coups, and political institutions. Review of International Organizations, 15(2), 531–551.

Bjørnskov, C., & Voigt, S. (2014). Constitutional verbosity and social trust. Public Choice, 161(1), 91–112.

Bologna Pavlik, J. B., Jahan, I., Young, A. T. 2023. Do longer constitutions corrupt? EuropeanJournal of Political Economy 77(C), ##-##.

Brennan, G., & Pardo, J. C. (1991). A reading of the Spanish Constitution (1978). Constitutional Political Economy, 2(1), 53–79.

Buchanan, J. M., & Tullock, G. (1962). The calculus of consent: Logical foundations of constitutional democracy. University of Michigan Press.

Callais, J., & Young, A. T. (2022). Does rigidity matter? Constitutional entrenchment and growth. European Journal of Law and Economics, 53(1), 27–62.

Callais, J., & Young, A. T. (2021). Does constitutional entrenchment matter for economic freedom? Contemporary Economic Policy, 39(4), 808–830.

Cheibub, J., Gandhi, J., & Vreeland, J. (2010). Democracy and dictatorship revisited. Public Choice, 143(1), 67–101.

Chilton, A., & Versteeg, M. (2017). Rights without resources: The impact of constitutional social rights on social spending. Journal of Law and Economics, 60(4), 713–748.

Colagrossi, M., Rossignoli, D., & Maggioni, M. A. (2020). Does democracy cause growth? A meta-analysis (of 2000 regressions). European Journal of Political Economy, 61(C), 101824.

Colon-Rios, J., & Hutchinson, A. C. (2012). Democracy and revolution: An enduring relationship. Denver Law Review, 89(3), 593–610.

Coppedge, M., Gerring, J., Knutsen, C. H., Lindberg, S. I., Teorell, J., Altman, D., Bernhard, M., Cornell, A., Fish, M. S., Gastaldi, L., Gjerløw, G., Glynn, A., Hicken, A., Lührmann, A., Maerz, S. F., Marquardt, K. L., McMann, K., Mechkova, V., Paxton, P., Pemstein, D., von Römer, J., Seim, B., Sigman, S., Skaaning, S-E., Staton, J., Sundtröm, A., Tzelgov, E., Uberti, L., Wang, Y., Wig, T., & Ziblatt, D. (2021). V-Dem Codebook v11.1. Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project.

de Lara, Y. G., Greif, A., & Jha, S. (2008). The administrative foundations of self-enforcing constitutions. American Economic Review, 98(2), 105–109.

de Vanssay, X., & Spindler, Z. A. (1994). Freedom and growth: Do constitutions matter? Public Choice, 78(3–4), 359–372.

Demzetz, H. (1967). Toward a theory of property rights. American Economic Review, 57(2), 347–359.

Dix, R. H. (1983). The varieties of revolution. Comparative Politics, 15(3), 281–294.

Doucouliagos, H., & Ulubasoglu, M. A. (2008). Democracy and economic growth: A meta-analysis. American Journal of Political Science, 52(1), 61–83.

Dove, J. A., & Young, A. T. (2019). US state constitutional entrenchment and default in the 19th century. Journal of Institutional Economics, 15(6), 963–982.

Dove, J. A., & Young, A. T. (2021). What is a classical liberal constitution? Independent Review, 26(3), 385–405.

Elkins, Z., & Ginsburg, T. (2021). What can we learn from written constitutions? Annual Review ofPolitical Science, 24(1), 321–343.

Elkins, Z., Ginsburg, T., & Melton, J. (2009). The endurance of national constitutions. Cambridge University Press.

Elster, J. (1979). Ulysses and the Sirens: Studies in rationality and irrationality. Cambridge University Press.

Feenstra, R. C., Inklaar, R., & Timmer, M. P. (2015). The next generation of the Penn world table. American Economic Review, 105(10), 3150–3182.

Freedom House. (2022). Freedom in the Word 2022: The Global Expansion of Authoritarian Rule. Washington, DC: Freedom House. https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/2022-02/FIW_2022_PDF_Booklet_Digital_Final_Web.pdf

Frosmi, J. O. (2012). Constitutional preambles at a crossroads between politics and law. Maggioli Editore.

Gardbaum, S. (2017). Revolutionary constitutionalism. International Journal of Constitutional Law, 15(1), 173–200.

Ginsburg, T. (2010). Constitutional specificity, unwritten understandings and constitutional agreement. In A. Sajo & R. Ultz (Eds.), Constitutional topography: Values and constitutions. Netherlands: Eleven International Publishing.

Ginsburg, T. (2010). Public choice and constitutional design. In D. Farber & A. J. O’Connell (Eds.), Handbook of public choice. UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Ginsburg, T., & Melton, J. (2015). Does the constitutional amendment rule matter at all? Amendmentcultures and the challenges of measuring amendment difficulty. International Journal of Constitutional Law, 13(3), 686–713.

Ginsburg, T., & Posner, E. A. (2010). Subconstitutionalism. Stanford Law Review., 62(6), 1583–1628.

Grier, K., & Maynard, N. (2016). The economic consequences of Hugo Chavez: a synthetic control analysis. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 125(C), 1–21.

Gutmann, J., Khesali, M., Voigt, S. (2021). Constitutional comprehensibility and the coordination of citizens: a test of the Weingast-hypothesis. University of Chicago Law Review Online. (April).

Hadfield, G. K., & Weingast, B. R. (2014). Constitutions as coordinating devices. In S. Galliani & I. Sened (Eds.), Institutions, property rights, and economic growth: The legacy of douglass North. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hall, J. C., & Lawson, R. A. (2014). Economic freedom of the world: An accounting of theliterature. Contemporary Economic Policy, 32(1), 1–19.

Hardin, R. (1989). Why a constitution? In B. Grofman & D. Wittman (Eds.), The Federalist papers and the new institutionalism. New York, NY: Agathon Press.

Hardin, R. (1999). Liberalism, constitutionalism, and democracy. Oxford University Press.

Harris, W. F., II. (1993). The interpretable constitution. Johns Hopkins Univ. Press.

Holcombe, R. G. (2018). Political capitalism: How economic and political power is made and maintained. Cambridge University Press.

Hayek, F. A. (1960). The constitution of liberty. University of Chicago Press.

Holmes, S. (1995). Passions and constraint: On the theory of liberal democracy. University of Chicago Press.

Huntington, S. P. (1968). Political order in changing societies. Yale University Press.

King, J. (2013). Constitutions as mission statements. In D. J. Galligan & M. Versteeg (Eds.), Social and political foundations of constitutions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kydland, F. E., & Prescott, E. C. (1977). Rules rather than discretion: The inconsistency if optimalplans. Journal of Political Economy, 85(3), 473–491.

Lachapelle, J., Levitsky, S., Way, L. A., & Casey, A. E. (2020). Social revolution and authoritarian durability. World Politics, 72(4), 557–600.

Leeson, P. T. (2011). Government, clubs, and constitutions. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 80(2), 301–308.

Marshall, M. G., Gurr, T. R. (2020). Polity5: Political regime characteristics and transitions, 1800–2018. Center for Systemic Peace.

Michelman, F. (1998). Constitutional authorship. In L. Alexander (Ed.), Constitutionalism: Philosophical foundations. New York, NY: Cambridge Univ. Press.

Mittal, S., & Weingast, B. R. (2011). Self-enforcing constitutions: With an application to democratic stability in America’s first century. Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization, 29(2), 278–302.

North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge University Press.

Ordeshook, P. C. (1992). Constitutional stability. Constitutional Political Economy, 3(2), 137–175.

Orgad, L. (2010). The preamble in constitutional interpretation. International Journal of Constitutional Law., 8(4), 714–738.

Persson, T., Roland, G., & Tabellini, G. (1997). Separation of powers and political accountability. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(4), 1163–1202.

Przeworski, A. (1991). Democracy and the market. Cambridge University Press.

Rosenbaum, P., & Rubin, D. (1983). The central role of the propensity score in observational studies of causal effects. Biometrika, 70(1), 41–55.

Schelling, T. C. (1984). Choice and consequence: Perspectives of an errant economist. Harvard University Press.

Skocpl, T. (1979). States and social revolutions: A comparative analysis of France, Russia and China. Cambridge University Press.

Tarabar, D., & Young, A. T. (2021). What constitutes a constitutional amendment culture? European Journal of Political Economy, 66, 101953.

Trimberger, E. K. (1972). A theory of elite revolutions. Studies in Comparative International Development, 7(3), 191–202.

Tsebelis, G. (2017). The time inconsistency of long constitutions: Evidence from the world. European Journal of Political Research, 56(4), 820–845.

Tsebelis, G., & Nardi, D. J. (2016). A long constitution is a (positively) bad constitution: Evidence from OECD countries. British Journal of Political Science, 46(2), 457–478.

Vahabi, M., Batifoulier, P., & Da Silva, N. (2020). The political economy of revolution and institutional change: The elite and mass revolutions. Revue D’ Economie Politique, 130(6), 855–889.

Vanberg, G. (2011). Substance vs. procedure: constitutional enforcement and constitutional choice. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 80(2), 309–318.

Versteeg, M., & Zackin, E. (2016). Constitutions unentrenched: Toward an alternative theory ofconstitutional design. American Political Science Review, 110(4), 657–674.

Voermans, W., Stremler, M., & Cliteur, P. (2017). Constitutional preambles: A comparative analysis. Edward Elgar.

Wagner, R., & Gwartney, J. (1989). Public choice and constitutional order. In J. Gwartney & R. Wagner (Eds.), Public choice and constitutional economics. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Weingast, B. R. (1997). The political foundations of democracy and the rule of law. American Political Science Review, 91(2), 245–263.

Weingast, B. R. (2005). The constitutional dilemma of economic liberty. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 19(3), 98–108.

World Bank. (2022). World development indicators. World Bank.

Young, A. T. (2019). How Austrians can contribute to constitutional political economy (and why theyshould). Review of Austrian Economics., 32(4), 281–293.

Young, A. T. (2021). The political economy of feudalism in medieval Europe. Constitutional PoliticalEconomy, 32(1), 127–143.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We thank participants at a March 2023 George Mason University economic history workshop for insightful discussion of an earlier draft. We also thank two anonymous referees for their helpful comments and criticisms.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Callais, J.T., Young, A.T. Revolutionary Constitutions: are they revolutionary in terms of constitutional design?. Public Choice (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-023-01094-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-023-01094-5