Abstract

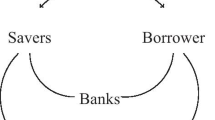

Lack of access to financial services is a problem for many; worldwide, one in four adults does not have a checking or savings account. Financial institutions with active, low-balance accounts often face considerable challenges compared to larger financial institutions (Black, 1979). Adding a fixed regulatory cost of servicing accounts can affect relative costs and thus generate an Alchian-Allen effect (the third law of demand) that leads financial institutions to quit servicing these low-balance accounts. Regulators may prefer this outcome as it is easier to regulate and extract rents from large financial institutions. Data indicates more underbanking in countries with lower income and more regulation. This article looks at the barriers traditional financial intermediaries often face in less developed nations and then looks at how fintech and cryptocurrencies enable bank alternatives to lower barriers to entry and expand financial inclusion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The use of financial services is unsurprisingly correlated with income, and 19.8% of households earning less than $15,000 per year do not have a checking or savings account, compared to 4.5 accounts per households overall (Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, 2022, p.75).

For example, the National Community Reinvestment Coalition’s Richardson and Edlebi (2022) look at the percentages of loans going to different groups and conclude that lower percentages of loans from certain banks to specific demographic groups indicate systemic redlining. Richardson and Edlebi (2022) conclude that banks are putting investors ahead of underserved communities: “Resources which could have been used to fulfill the commitments it made to the marginalized went to investors instead.“ Those who believe that financial institutions that wrongfully prioritize shareholder well-being over the marginalized typically support various inclusion mandates for increasing access.

For a history of the redlining maps stemming from the New Deal agency Home Owners’ Loan Corporation see, Aaronson et al. (2021).

The remaining financial institutions, such as credit unions that sought to serve minorities, historically faced restrictions on certain types of lending, such as offering 30-year mortgages or making commercial loans (Black & Dugger, 1981; Black, 1981). Moreover, any potential new banks would have to receive a charter from a state banking commission or the U.S. Comptroller of the Currency and demonstrate a “Public Need for New Banks,“ which is more difficult in areas where minority customers are more likely to have lower balance accounts (Black & Lundsten, 1977).

Politicians and regulators might individually benefit from the revolving door issue where they later receive payments from banks they regulated. For example, Barney Frank individually collected $2 million from Silicon Valley Bank for being on its board, with Frank stating, “I need to make money” (Franklin & Gandel, 2023). For an overview of the potential beneficiaries in the economic theories of regulation, see Thomas and Thomas (2022), Peltzman (2022), and Yandle (2022).

Black and Schweitzer (1985, p.13) also discuss these same challenges related to loans and conclude that differences in lending across different demographic groups “is not prima facia evidence of discrimination.“ They write, “Such results call into question the rationale for the continued existence of the array of consumer protection laws and implementing regulations designed to prohibit lending discrimination. Indeed, the cost of compliance could act to discourage mortgage lending” (Black and Schweitzer, 1985, p.13).

Adam Smith ([1776] 1982, p.853) also wrote about how a fixed charge license fee on businesses small and large alike “must necessarily give some advantage to the great, and occasion some oppression to the small dealers.“ Smith ([1776] 1982, p.853) adds, “If the tax had been considerable, it would have oppressed the small, and forced almost the whole retail trade into the hands of the great dealers.” Thomas (2019), Manish and O’Reilly (2019) and Chambers and O’Reilly (2022) discuss how financial regulations are likely to be regressive and disproportionally harm smaller firms and lower income individuals.

I refer to a cryptointermediary as any firm or middleman within the cryptocurrency industry that helps parties hold or transact in cryptocurrencies. Few cryptointermediaries would be classified as being close to a full scale bank, but many provide services traditionally offered by banks.

Barclays has done business in Africa for over a century and is the largest shareholder in the continent’s third-largest bank, Absa Group (formerly Barclays Africa), which owns banks in Botswana, Ghana, Kenya, Mauritius, Mozambique, Seychelles, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia.

Cline et al. (2022) analysis indicate a correlation between lower regulation and more trust and better market outcomes among countries. Heinemann and Schüler (2004, p.114) present evidence that countries with more financial regulations tend to less banking services and argue that incumbent firms work to shape regulations to create barriers to entry.

Of course, some people choose to be unbanked and their decision might not change if regulations were decreased. In its survey of unbanked Americans, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (2022, p.3) finds that 8.4% and 13.2% the unbanked list “don’t trust the banks” or “avoiding a bank account gives more privacy” as their primary reason for not using a bank.

These numbers are not directly comparable because stablecoin settlement includes both final transfer of funds among individuals akin to someone paying someone using a charge or credit card but also settlement of back and forth trades among exchanges. Both are economically important functions but the latter statistic has near limitless potential for expansion as trading volume using stablecoin increases.

In contrast to modern state capacity advocates who assume an expansion of markets can only come after government creates the right legal and regulatory support for markets, Rajan (2004, p.56) argues that an “assume a perfect world” approach is a poor guide to policy.

References

Aaronson, D., Hartley, D., & Mazumder, B. (2021). The effects of the 1930s HOLC ‘redlining’ maps. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 13(4), 355–392.

Akinwotu, E. (2021). Out of control and rising: Why Bitcoin has Nigeria’s government in a panic. The Guardian, July 31, 2021.

Alchian, A. A., & Allen, W. R. (1964). University economics: Elements of inquiry. Wadsworth Publishing Company.

Bates, R. H., Greif, A., Levi, M., Rosenthal, J. L., & Weingast, B. R. (1998). Analytic narratives. Princeton University Press.

Baydakova, A. (2021). Thriving under pressure: Why crypto Is booming in Nigeria despite the banking ban. Coin Desk, July 6, 2021.

Benson, B. (1990). The enterprise of law. Pacific Research Institute.

Benson, B. (1998). To serve and protect. New York University Press.

Bitcoin Magazine (2022). Bitcoin app Strike launches instant, cheap remittances to Africa. Bitcoin Magazine, December 6, 2022.

Black, H. A. (1979). Black financial institutions and urban revitalization. Review of Black Political Economy, 10(1), 44–58.

Black, H. A. (1981). Review of Financing Black Economic Development by Timothy Bates and William Bradford. Journal of Money Credit and Banking, 13(1), 114–115.

Black, H. A., & Dugger, R. H. (1981). Credit union structure, growth and regulatory problems. The Journal of Finance, 36(2), 529–538.

Black, H. A., & Lundsten, L. L. (1977). Factors used to determine the public need for new banks: Comment. Southern Economic Journal, 44(2), 385–388.

Black, H. A., & Schweitzer, R. L. (1985). A canonical analysis of mortgage lending terms: Testing for lending discrimination at a commercial bank. Urban Studies, 22(1), 13–19.

Black, H. A., Fields, A. M., & Schweitzer, R. L. (1990). Changes in interstate banking laws: The impact on shareholder wealth. Journal of Finance, 45(5), 1663–1671.

Bordo, M. D., & Duca, J. V. (2018). The impact of the Dodd-Frank Act on small business. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series Working Paper No. 24501, April, 2018.

British Broadcasting Corporation (2021). Cryptocurrencies: Why Nigeria is a global leader in Bitcoin trade. BBC News, February 28, 2021.

Chambers, D., & O’Reilly, C. (2022). The economic theory of regulation and inequality. Public Choice, 193, 63–78.

Cline, B., Williamson, C. R., & Xiong, H. (2022). Trust, regulation, and market efficiency. Public Choice, 190, 427–456.

Coin Metrics (2022). State of the network: 2022 review. Coin Metrics’ State of the Network, Issue 186, December 20, 2022.

Cowen, T. (2021). Libertarianism isn’t dead. It’s just reinventing itself. Bloomberg, April 4, 2021.

Emefiele, G. (2022). About - Godwin Emefiele. Official website of Godwin Emefiele, Governor of CBN.

Ericsson. (2023). Mobile financial services. Telefonaktiebolaget LM Ericsson.

Evans, D. S., & Pirchio, A. (2015). An empirical examination of why mobile money schemes ignite in some developing countries but flounder in most. Review of Network Economics, 13(4), 397–451.

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. (2022). 2021 FDIC national survey of unbanked and underbanked households. Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation.

Franklin, J., & Gandel, S. (2023). Barney Frank defends role at Signature Bank: ‘I need to make money.’ Financial Times, March 15, 2023.

Global System for Mobile Communications Association. (2022). State of the industry report on mobile money 2022. Global System for Mobile Communications Association.

Grauer, K. (2022). How crypto aids residents’ economic needs in Sub-Saharan Africa. Busy Continent, October 21, 2022.

Gwartney, J., Lawson, R., Hall, J., & Murphy, R. (2021). Economic freedom of the world: 2021 Annual report Fraser Institute.

Hamacher, A. (2020). Nigeria is emerging as a true Bitcoin nation: Nigeria’s tech-savvy youth and struggling economy have created the perfect circumstances for Bitcoin usage to thrive, especially in commerce. Decrypt, November 26, 2020.

Heinemann, F., & Schüler, M. (2004). A stiglerian view on banking supervision. Public Choice, 121, 99–130.

Hertig, A. (2021). Bitcoin ‘can’t be stopped’: Nigerians look to P2P exchanges after crypto ban. Coin Desk, February 9, 2021.

Idriss, U. S., Ahmad, A., Bichi, A. M., & Umar, U. (2022). Insights into the study of factors influencing the rapid adoption of mobile money in Nigeria and Kenya. International Journal of the Trans African Universities and Allied Institution Research Development Network, 14, 265–276.

International Trade Administration. (2021). Nigeria - prohibited and restricted imports. Country Commercial Guides. International Trade Administration.

Komolafe, B. (2021). Cryptocurrency ban’s to protect Nigerians, financial system — CBN. Vanguard Nigeria, February 8, 2021.

Krugman, P. (2021). Technobabble, libertarian derp and Bitcoin. New York Times, May 20, 2021.

Krugman, P. (2022). Is this the end game for crypto? New York Times, November 17, 2022.

La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. (2002). Government ownership of banks. Journal of Finance, 57(1), 265–301.

Leeson, P. T. (2007). Efficient anarchy. Public Choice, 130(1–2), 41–53.

Leeson, P. T. (2008). Coordination without command: Stretching the scope of spontaneous order. Public Choice, 135(1–2), 67–78.

Leeson, P. T. (2009). The calculus of piratical consent: The myth of the myth of social contract. Public Choice, 139(3–4), 443–459.

Leeson, P. T. (2014). Anarchy unbound: Why self-governance works better than you think. Cambridge University Press.

Leeson, P. T. (2020). Economics is not statistics (and vice versa). Journal of Institutional Economics, 16(4), 423–425.

Lindrea, B. (2022). Nigeria set to pass bill recognizing Bitcoin and cryptocurrencies. Coin Telegraph, December 19, 2022.

Maishera, H. (2022). Strike partners with Bitnob to improve remittance payments into Africa. Coin Corner, December 6, 2022.

Manish, G. P., & O’Reilly, C. (2019). Banking regulation, regulatory capture and inequality. Public Choice, 180, 145–164.

McChesney, F. S. (1987). Rent extraction and rent creation in the economic theory of regulation. Journal of Legal Studies, 16(1), 101–118.

Mises, L. V. (1953). Theory of money and credit. Yale University Press.

Mojeed, A. (2021). Naira sees biggest plunge ever after CBN forex ban. Premium Times, July 28, 2021.

Nigerian Current (2019). ‘Don’t give a cent to anybody to import food into the country,’ Buhari tells CBN. Nigerian Current, August 14, 2019.

Odunsi, W. (2021). Why we banned cryptocurrency in Nigeria – CBN. Daily Post Nigeria, February 7, 2021.

Okeleke, K., & Shahid, N. (2022). Payment service banks in Nigeria: Opportunities and challenges. Global System for Mobile Communications Association.

Peltzman, S. (2022). The theory of economic regulation’ after 50 years. Public Choice, 193, 7–21.

Posner, R. (1974). Theories of economic regulation. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series Working Paper No. 41, May 1974.

Powell, B. W., & Stringham, E. P. (2009). Public choice and the economic analysis of anarchy: A survey. Public Choice, 140, 503–538.

Powell, B. W., Ford, R., & Nowrasteh, A. (2008). Somalia after state collapse: Chaos or improvement? Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 67(3/4), 657–670.

Preston, B. (2018). In Muncie, a legacy of segregation and wealth inequalities. Star Press, February 3, 2018.

Razzolini, L., Shughart, W. F., & Tollison, R. D. (2003). On the third law of demand. Economic Inquiry, 41(2), 292–298.

Richardson, J., & Edlebi, J. (2022). Redlined. National Community Reinvestment Coalition.

Russon, M. A. (2019). The battle between cash and mobile payments in Africa. BBC News, February 19, 2019.

Shughart, W. F., & Thomas, D. W. (2014). What did economists do? Euvoluntary, voluntary, and coercive institutions of collective choice. Southern Economic Journal, 80(4), 926–937.

Skarbek, D. (2020). Qualitative research methods for institutional analysis. Journal of Institutional Economics, 16(4), 409–422.

Smith, A., & [1776] (1982). An inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations. Oxford University Press.

Statista (2022). Global consumer survey Statista.

Stigler, G. J. (1971). The theory of economic regulation. Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science, 2(1), 3–21.

Stringham, E. P. (2015). Private governance: Creating order in economic and social life. Oxford University Press.

Thomas, D. W. (2019). Regressive effects of regulation. Public Choice, 180, 1–10.

Thomas, D. W., & Thomas, M. D. (2022). Regulation, competition, and the social control of business. Public Choice, 193, 109–125.

Trading Economics. (2022). Inflation rate: Africa. Trading Economics.

Umuteme, B. (2020). Forex restriction: Conserving foreign exchange through import ban. Blueprint Newspaper, July 24, 2020.

United Nations. (2022). Birth Registration. United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund West and Central Africa Regional Office.

Vodaphone (2023). What is M-PESA? Vodaphone.

What’s Next Media and Analytics. (2021). The digital currency shift: The cross-border remittances report. What’s Next Media and Analytics.

World Bank (2021). Remittance prices worldwide World Bank.

World Bank (2022b). World development indicators World Bank.

World Bank. (2022a). The global findex database 2021. World Bank.

Yandle, B. (2022). George J. Stigler’s theory of economic regulation, bootleggers, Baptists and the rebirth of the public interest imperative. Public Choice, 193, 23–34.

Young, M. (2021). Nigerian crypto adoption rises despite gov’t crackdown. Coin Telegraph, Aug 2, 2021.

Acknowledgement

I thank Harold Black, Brian Cutsiger, Ramon DeGenarro, Kevin Grier, Robin Grier, Claudia Williamson Kramer, William Luther, Florence Muhoza, Jamie Bologna Pavlik, Benjamin Powell, Daniel J. Smith, Peter Yakobe, and seminar participants at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, the Association of Private Enterprise Education, and Texas Tech University for helpful comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Stringham, E.P. Banking regulation got you down? The rise of fintech and cryptointermediation in Africa. Public Choice 197, 455–470 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-023-01090-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-023-01090-9

Keywords

- Fintech

- Bitcoin

- Financial intermediation

- Unbanked

- Forex

- Economic theory of regulation

- Deregulation

- Financial services