Abstract

This study aims to synthesize the extant research on the Born Global Firms (BGF) phenomenon, mainly focusing on the Asia Pacific region (APAC). We adopt the systematic literature review methodology to identify the main context-specific drivers (‘success factors’) and outcomes of BGFs’ accelerated internationalization and the challenges they face before, during, and after global expansion. The analysis and evaluation of relevant studies reveal several critical variables that need to be extensively investigated (separately and in tandem) by scholars in order to advance existing theories and, at the same time, explain the out-of-pattern behaviors of BGFs outside the typical ‘Western economy’ context. Among the core variables are international entrepreneurial orientation and culture adoption, organizational learning and networking strategies, global strategic human capital and network resources (as predictors of BGFs’ international performance) and resource constraints, institutional and cultural distances, and liabilities of newness, smallness, foreignness, outsidership, and emergingness (as constraints to BGFs’ success). By identifying the research gaps and proposing a comprehensive framework with promising avenues for future research into the phenomenon of BGFs from the APAC region, this study helps enhance our understanding of the global strategy formation and execution processes of international new ventures from ‘the East’ and stimulate interdisciplinary dialogue between international business, strategy, and entrepreneurship scholars.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

International business (IB) scholarship in the internationalization processes of small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) from non-Western contexts has increased rapidly in recent years (e.g., Mukherjee, Makarius, and Stevens, 2021; Nuruzzaman et al., 2020). Within the last five years, IB researchers have delved deeper into the examination of the behaviors of firms operating in/from various contexts and settings (Elbanna, Hsieh, and Child, 2020) and re-evaluated the role of different location- and firm-specific factors, including environmental munificence (Guo & Wang, 2021), firm age (Liou & Rao-Nicholson, 2019), size (Zhu, Warner, & Sardana, 2020) and ownership (González & González-Galindo, 2022), in the survival and growth of internationalizing/ed new ventures (Child et al., 2022). For a more nuanced understanding of different internationalization strategies adopted by SMEs from the East (in particular), special scholarly attention has been devoted to born global firmsFootnote 1 (BGFs) from the APACFootnote 2 region – overwhelmingly small, young internationally-orientated firms that from (or near) inception obtained a substantial portion of total revenue from foreign sales (Knight & Cavusgil, 2005).

As critical players in the global arena, BGFs are actively reshaping the global business landscape (Hennart et al., 2021; Cavusgil and Knight, 2015), introducing nonconventional, idiosyncratic strategies of ‘doing business in multiple country environments’ (Luo & Tung, 2018; Tsai & Eisingerich, 2010) and building various cross-border partnerships and global networks (Bai et al., 2021). They have the distinct advantage of being knowledge-intensive, low-cost players that advertise innovative, self-developed technological products. Despite their flexibility and adaptability (Li, Zhang, and Shi, 2020), they face numerous challenges before, during, and after global expansion – severe resource constraints, a lack of institutional support system, and fierce international competition.

Most studies on BGFs have focused on the North American, European, and/or Australian contexts, all of which are affluent economic societies. Eastern markets, unlike the more advanced Western economies, tend to be more dynamic, complex, and heterogeneous; scholars often characterize emerging market countries from the APAC by rapid economic growth, weak institutional context, knowledge isolation, and market sophistication (Rui, Cuervo-Cazurra, and Un, 2016). Local firms have limited access to strategic human and financial capital, institutional support, networks, and other valuable resources, forcing them to be more aggressive in their internationalization endeavors. Executives must account for the geographical and socio-cultural distances between their firms’ home and host countries, as these may deter further international expansion (Li et al., 2020).

While the BGF phenomenon is becoming more widespread, a full assessment of its prevalence in the APAC context still needs to be made. The number of Asian enterprises that went global through foreign direct investment has grown by over 4% (UNCTAD, 2021). While economies such as India, China, and New Zealand have emerged as the world’s rapidly expanding nations, countries like South Korea, Taiwan, and Vietnam have experienced extraordinary growth, successfully transitioning from emerging to more advanced economies (Paul & Dikova, 2016). We argue that for BGFs from the APAC region to stay relevant and competitive, they must actively learn and adapt to the global and regional business environments and specific institutional contexts as they strive to launch and expand from the APAC to other locations.

However, more context-focused research on the topic is required. How BGFs from the APAC acquire, transform, and exploit ‘glocal’ knowledge resources to enhance international performance and competitiveness may vary significantly compared to BGFs from other markets. Their ownership and location (dis)advantages, institutional arrangements, and dynamic capabilities are expected to diverge significantly within the region. Though prior research partially illuminated the critical role of expansion strategy and location choice, global networks, and entrepreneurial orientation in ensuring long-term survival (Knight & Liesch, 2016), there is a lack of research concentrating on APAC’s regional characteristics and idiosyncrasies.

Similar to previous works on BGFs, we believe the more traditional Uppsala approach (alone) may not adequately explain the underlying mechanisms of BGFs’ rapid internationalization. The strategic actions through which BGFs alter their management systems, rules, practices, and resource bases to maintain/improve productivity and gain market legitimacy are highly context-specific, which requires the use of both the top-down deductive and bottom-up inductive reasonings to extend existing theories and, at the same time, explain the out-of-pattern behaviors of BGFs outside the typical ‘Western economy’ context. How BGFs from the APAC region interact with the external environment may differ extensively from their Western counterparts regarding their effect on survival and growth.

We consequently combine different theoretical lenses, specifically the institution-based view (Su, 2013; McGaughey, 2007), the legitimacy (Tan & Mathews, 2015; Wood et al., 2011), and organizational learning perspectives (Buccieri et al., 2021; Gerschewski et al., 2018; Zhou et al., 2012), reconceptualizing and linking the existing constructs/theories to a specific context – APAC. The institution-based view, in particular, may help unveil how the institutional differences (e.g., multiple stakeholder evaluations in domestic and global markets) and institutional failures (e.g., infrastructure constraints, regulatory requirements, limited access to networks, etc.) shape the internationalization process of APAC firms (McGaughey, 2007). Meanwhile, the legitimacy perspective may enhance scholarly understanding of how internationalizing BGFs acquire legitimacy, a critical asset needed for firm survival, reputation building, and stakeholder engagement in the international marketplace (Prashantham et al., 2019a, b; Wood et al., 2011). Lastly, the organizational learning perspective may explain how the learning opportunities stemming from BGFs’ intentions to expand to other markets rapidly are discovered and exploited, how foreign business knowledge and international experience are acquired and further exploited by these firms to boost innovativeness, address the unique environmental challenges to which they are exposed, and increase chances of international success (Falahat & Migin, 2017; Khan and Lew, 2018; Zhou et al., 2010; De Clercq and Zhou, 2014).

Given the widespread but fragmented nature of the literature as well as the theoretical relevance of BGFs from/in the APAC for IB and entrepreneurship research (Paul & Dikova, 2016; Zuchella, 2021), a comprehensive review and context-focused analysis of the literature is required. This study does not wish to provide novel theoretical explanations of the phenomenon of BGFs in the APAC; it specifically aims to identify patterns in scholarly works and discourse on the topic and develop a multi-domain research agenda. In pursuit of this goal, we define the following research questions: (1) What are the primary drivers (success factors) and outcomes of the internationalization of BGFs from the APAC? (2) What major challenges and barriers BGFs face during accelerated internationalization?

This research contributes significantly to the literature on BGFs in the APAC region by synthesizing prior studies and providing a conceptual framework for categorizing BGFs’ main success factors and challenges. In addition, it helps construct the meaning of the competitive advantages of BGFs from the APAC by conducting a systematic review and identifying gaps in the literature that require further investigation. To do so, we draw upon recent research on BGFs (e.g., Dzikowski, 2018; Øyna & Alon, 2018) but focus exclusively on the APAC, delving into the exploration of the learning opportunities as well as constraints that these firms may face along their internationalization path. This review lets us gain insight into how BGFs in/from the APAC region, operating primarily in more innovation-intensive industries, optimize their business processes, overcome difficulties, and stay consistent in their internationalization. In addition, our framework contributes significantly to organizational learning and institutional theories by encapsulating BGFs’ internationalization process and identifying critical areas for future studies. Lastly, the theoretical and policy implications are discussed, and we highlight how research on BGFs from non-Western settings helps address the demand for research-practice synergy (Shams et al., 2022).

In the remainder of the paper, we outline the procedures for undertaking the systematic literature review, explaining our steps to ensure validity and reliability. Next, we present the findings derived from the analysis, organizing them around the two research questions: the drivers of internationalization of BGFs from APAC and challenges associated with BFFs in and from APAC. We conclude with discussions and future research directions, providing further avenues to advance this literature.

Methodology

This study adopts the systematic literature review methodology (Tranfield et al., 2003; Snyder, 2019; Budhwar et al., 2019), which consists of the following steps: (1) the planning stage (the objective of the review and database selection) (2) the identification and retrieval of academic articles from major abstract and citation databases (3) screening and full-text assessment of relevant papers published in top-tier peer-reviewed journals; (4) evaluation and synthesis of the literature. Following the procedural guidelines and best practices described in impactful literature review papers (e.g., Budhwar et al., 2019), we conducted a thorough search in Scopus (in March 2022), using multiple search queries and keywords (Table 1). When extracting data from Scopus, by default, it considers the paper that may be published at any time of the year. The first step yielded 195 papers. We further conducted a series of quality checks to ensure only validated and reliable sources of data were further used in our analysis – only those papers that were published in journals ranked 4*, 4, or 3 by the Chartered Association of Business Schools in its Academic Journal Guide (AJG, 2021) were retained. However, considering our research questions and objectives, we made exceptions for journals that focused on the APAC: Asia Pacific Journal of Management, Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration, Asia Pacific Business Review, Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, and Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy. These steps generated a preliminary sample of 86 articles.

After the full-text assessment, we excluded 20 articles that either focused on unrelated and/or irrelevant issues (e.g., MNEs’ expansion, development of a scale for international opportunity identification) or did not explicitly consider BGFs and/or the APAC context. This step produced a sample of 66 articles. We further adopted the qualitative coding method put forth by Cortez et al. (2021), Snyder (2019), and Paul and Criado (2020). In particular, we used a table matrix based on a predefined framework and codes, such as the study context and level of analysis, theoretical and analytical frameworks, major drivers, challenges and barriers, and outcomes of internationalization of BGFs in the APAC context, which allowed us to engage with the literature in a meaningful way, explore the main themes, structures, and patterns in the research, and stimulate story narration. Two expert authors independently coded the articles to address potential reliability and validity concerns. A third expert monitored the process and resolved disagreements among the two primary coders.

Findings & Discussion

Drivers of internationalization of BGFs from APAC

Learning and networking Footnote 3 strategies for BGFs’ internationalization

The analysis and synthesis of the 66 articles reveal that the core assets in successfully providing IB knowledge and accelerated global expansions are international network resources and learning capabilities (Falahat & Migin, 2017; Khan & Lew, 2018; Falahat et al., 2018; Bai et al., 2016). The study by Rasmussan et al. (2001), in particular, focuses on entrepreneurs’ motivation, ambition, and experience, which, in turn, facilitate the two major founding process activities – sensemaking (or the founder’s attempt to “construct meaning to his/her plans and ideas together with other actors” p.80) and networking. Furthermore, they depict organization formation (pre-organization) as an interaction between propensity, intention, decision, sensemaking, and networking (Rasmussan et al., 2001).

Chetty and Campbell-Hunt (2004) compare BGFs to regional and global firms from New Zealand concerning their market entry modes and growth, product ranges, reactions to the gusher (i.e., rapid international growth), product leadership, firm type, production, marketing, and prior foreign experience of the founders. BGFs tend to be hi-tech manufacturing and service firms that are world leaders in their specialized-for-the-niche-markets products. They use active learning and networking strategies to manage the gusher and its destabilizing effects effectively.

The network approach to internationalization and the firm’s resource- and knowledge-based views have been proposed to understand the importance of networks and networking activity in developing BGFs’ dynamic capabilities and competitive advantages (Loane & Bell, 2006). In this approach, firms may overcome resource deficiencies and develop their knowledge repositories by building new networks rather than relying on existing networks. Furthermore, embedded social capital and the internationally acquired, dynamically evolving routines to efficiently and effectively manage valuable knowledge are crucial resources and capabilities for BGFs’ successful internationalization and enhanced performance (Loane & Bell, 2006). Loane and Bell (2006), in particular, mention the use of ‘sweat capital’ by an Australian firm (basically, tapping into the networks of close friends, family, (former), and colleagues to provide services and advice voluntarily) to fill the knowledge and skills gaps in the organization.

Similarly, Zhou et al. (2007) investigated the role of international social networks (as a mediating factor) in the association between the internationalization process and the performance of the firms. These researchers focus on guanxi-related connections, which are crucial for the internationalization process involving Chinese players. Terjesen et al. (2008) highlight the vital role of entrepreneurs’ networking and network resources; however, the authors focus on a more symbiotic relationship – indirect internationalization of BGFs via multinational corporations. This intermediated mode is juxtaposed with the direct way; the underlying idea is that a venture’s innovation is channeled through existing multinationals.

What makes the newcomers successful is their ability to address high entry barriers by taking advantage of the more prominent players’ supply chains. The BGFs create strategic partnerships with these firms to access specific technology and markets and limit potential liabilities of smallness, foreignness, and newness. In the meantime, neither mode of internationalization is optimum: context matters. Knowledge spillovers are geographically bounded within a region (Terjesen, O’Gorman, and Acs, 2008).

Gassmann and Keupp (2007) claim that SMEs focus on developing experimental knowledge that can be transferred within and across multiple countries. The BGFs’ idiosyncratic knowledge base is what helps build and sustain the capabilities that are required for successful internationalization (rather than tangible resources), product homogeneity (not bound to the cultural peculiarities of foreign markets), uniqueness of innovation, and specialization in international value chains along with the firm’s embeddedness in global networks are crucial factors for the generation and effective exploitation of specialized knowledge. The Australian case, for instance, demonstrates that it is beneficial to locally produce a globally homogenous worldwide product that does not need to be modified based on the peculiarities of single markets outside the country. Gassman and Keupp (2007) state that the underlying mechanisms of overcoming the resource crunch to generate sustained competitive advantages cannot be solely explained by KBV; a network perspective should be adopted.

Meanwhile, Chandra et al. (2012) argue that a path-dependent mechanism of opportunity formation drives the accelerated internationalization phase; international operations are formed by the domestic and international channels in which essential actors have previously operated. Similarly, Prashantham and Birkinshaw (2015) also investigated how inter-organizational networks may help create opportunities for BGFs to internationalize successfully. However, unlike most studies on this topic, this research explores the circumstances under which home-country ties, rather than the host, are more likely to affect the internationalization process positively. They find that strong home-country relationships negatively affect firms’ international growth.

Pellegrino and McNaughton (2015) explore how the learning mode and foci of New Zealand BGFs co-evolved during different internationalization phases (pre-, early, and later). The main findings demonstrate that market research, learning from networks, and congenital learning affect firms’ competitive advantage and product/market scopes. Furthermore, Tan and Mathews (2015) argue that the accelerated expansion of firms from emerging economies is crucial to the firm’s linkage, leverage, and learning processes. Along the same line, Gerschewski et al. (2018) also analyze the driving factors of post-entry performance of New Zealand and Australian INVs; they emphasize the role of learning capabilities, niche strategy, and networks (cf., Pellegrinoa and McNaughton (2017).

Finally, utilizing multiple sources of information and pursuing innovative ventures are essential success factors for BGFs to develop their born-global strategy and decrease the likelihood of early failure in foreign markets. This also helps BGFs remain international from their launch and enables them to expand into new markets simultaneously (Hull et al., 2020). Falahat et al. (2018) argue that an optimum marketing plan could further increase the performance of a few APAC-born globals in international markets. Thus, it is proposed that the BGFs leadership must consider creating relationships with local federal agencies, industry groups, essential customers, and other stakeholders in foreign markets to acquire vital market information.

International entrepreneurial orientation, strategy, and culture as the core predictors of BGFs’ international success

De Clercq and Zhou (2014) and De Clercq and Zhou (2014) propose that focused international learning attempts serve as a fundamental behavioral basis through which BGFs may strengthen their international competitiveness. The strategic proclivity of enterprises to take risks, be inventive, and be assertive - their entrepreneurial tactic orientation – boosts their engagement with foreign market knowledge and, as a result, generates learning benefits of novelty.

Similarly, Buccieri, Javalgi, and Jancenelle (2021) suggest that international entrepreneurial culture is a core predictor of superior performance. Embracing such a culture that facilitates entrepreneurial activities internationally helps BGFs develop dynamic capabilities (i.e., in response to environmental changes, they adopt sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring capabilities) and address resource constraints and various liabilities of smallness, foreignness, newness, and emergingness. Meanwhile, Ciravegna et al. (2014) shed light on the export inception of local low-tech SMEs from China and argue that the focused first search for global customers positively affects the scope and intensity of internationalization. Likewise, Mort et al. (2012) identify four mutually non-exclusive entrepreneurial strategies that lead to accelerated internationalization and enhanced performance in Australian BGFs: development of opportunities, revolutionary products based on customer interaction, resource expansion, and legitimacy.

Meanwhile, Zhou (2007) contrasts the traditional and born-global views and finds the nature and knowledge source of foreign markets to drive the difference between the two approaches. Moreover, the international entrepreneurial proclivity of BGFs - their proactive, innovative, and risk-taking behaviors – is a crucial success factor. The baseline assumption is that BGFs are strongly motivated to operate globally; they are more aggressive, committed, and experimental in their entrepreneurial actions to build successful global businesses. Knowledge-intensive BGFs from APAC, in particular, have a lower home country demand (Murmann et al., 2015), which facilitates the translation from founders’ intention to go abroad to real action in the form of international and domestic partnership formation. It provides firms with dynamic capabilities to acquire, assimilate, and transform market knowledge, fostering responsiveness to the external environment and boosting internationalization pace and performance. Furthermore, Zhou (2007) sees international market information through the lens of entrepreneurial sources and not based on the time-bound expertise gained through worldwide activities.

International human capital and internal social capital as valuable resources for BGFs’ global expansion

International human capital is characterized as “knowledge of international best practices, global industry standards, international trade laws, modular systems and processes, cross-border industry networks, and other transportable forms of experience applicable across multiple firms and countries” (Morris et al., 2016, p.729), is a valuable resource that BGFs can use to fuel their internationalization decision-making processes. Along with managerial socio-cognitive aspects, it is an entrepreneurial intentionality factor that facilitates the internationalization of firms, primarily stemming from remote small economies (Kahiya, 2020). For instance, Bai et al. (2017) conclude that returnee entrepreneurs’ foreign experience enables them to develop overseas market understanding and influences their worldwide market engagement and degree of diversification. These valuable knowledge resources increase the success of new venture internationalization (Arte, 2017).

Studies support the general assumption that global growth and expansion of new ventures are contingent upon forming an experienced and highly functional top management team (TMT). The skills, abilities, expertise, and international experience of the founder and TMT members and the in-group functional, operational, industrial, and educational knowledge diversity demonstrate the breadth of information that assists decision-making (Loane, Bell, and McNaughton, 2007). According to Su et al. (2019a, b), highly educated executives have a greater intent for processing information and idea generation and accept calculated risks. Loane et al. (2007) explore the importance of knowledge diversity within the TMT for rapid internationalization. The team-level human and social capital coupled with valuable expertise, experience, competencies, skills, and international networks is shown to significantly influence the creation of dynamic capabilities and acquisition of valuable external resources by the BGFs. Changes in the teams’ structures directly affect firms’ ability to rapidly internationalize and reach broader markets.

Meanwhile, the internal social capital entrenched in young enterprises enables them to foster an international learning effort focused on successfully aligning resources and activities associated with international expansion. Internal social capital, or “the linkages among individuals and groups within an organization that is grounded in dynamics of individual and collective behaviors that facilitate cooperation and provide access to new business opportunities” (Sanchez-Famoso et al., p.33), is associated with the inherent learning benefits of novelty and capturing the opportunity contributes to the research on young firms’ quick and accelerated expansion (Bai et al., 2020). According to Kumar and Sharma (2018), corporate culture, which includes continual learning, creative thinking, collaboration and sharing, and customer-centricity, favorably promotes new enterprises’ predisposition towards internationalization. Cooperation and sharing cultures can assist them in addressing scarcity and enhancing potential discovery in the world market. Partnerships with notable partners and stakeholders and a place in the high value-added chain are crucial for knowledge-intensive INVs to cross the chasm and boost their prospects of becoming MNCs in the global ecosystem (Li & Deng, 2017).

When new ventures from the APAC penetrate global markets, co-ethnic ties and relationships with foreign MNEs are essential. As these firms strive to strengthen their capabilities, interpersonal diaspora relationships and inter-organizational MNE ties may contribute to their internal and external legitimacy. Furthermore, co-ethnic managers employed by MNEs act as possible triggers for the core cross-border legitimacy (Prashantham et al., 2019).

Outcomes of internationalization of BGFs from APAC

Our literature review reveals that exploring the outcomes of BGFs’ internationalization remains a secondary focus for scholars (the primary foci being drivers and challenges these firms face at different stages of international expansion). To evaluate their international success, several indicators are usually considered (Gerschewski & Xiao, 2015): the pace of entry and financial performance (Zhou, 2007; Loane et al., 2007), acquired legitimacy (Wood et al., 2011), new ventures’ formation, survival, and growth prospects (McGaughey, 2007), boosted innovation (Weerawardena et al., 2015), learning advantages of newness (Zhou et al., 2010; Clercq & Zhou, 2014; De Clercq et al., 2014), and sustained competitive advantage (Pellegrino & McNaughton, 2015).

Extant literature also identifies specific patterns in the strategic behaviors of BGFs expanding from underdeveloped and/rapidly or highly competitive markets to more munificent, advanced markets (Khavul et al., 2010a, b; Wood et al., 2011; Tang, 2011; Zhou et al., 2012; Khavul et al., 2012): positive performance outcomes are a consequence of firms’ high levels of commitment and responsiveness to global demands combined with the effective and efficient identification, transformation, and exploitation of valuable and rare intangible resources (inter alia, technological and managerial knowledge, entrepreneurs’ networks of connections, team, and firm experience). The temporal changes in the external environment create temporal misfits between the firm and its environment, consequently affecting the extent, scope, and velocity of the international expansion process (Khavul et al., 2010a, b). Hence, establishing an appropriate level of entrainment, or synchronization with the firms’ most important international customers, helps BGFs acquire legitimacy, attain a temporal fit, and realize their growth strategies more effectively.

Challenges associated with BGF in and from APAC

Our analysis reveals that the challenges BGFs face during cross-border expansion are usually discussed to a lesser degree than the ‘success’ factors of internationalization. Their complexity and severity depend on the specific institutional context and the region the BGF comes from (or is trying to enter), which consequently affects the type of actions the firm takes to reach particular organizational outcomes. Using the traditional IB and entrepreneurship approaches, scholars explore the different strategies firms adopt (e.g., the creation of various forms of networks and cross-border alliances) to deal with environmental uncertainty, resource scarcity, negative legitimacy spillovers, knowledge gaps, cultural and institutional barriers, as well as the various liabilities of newness, smallness, and outsidership (e.g., Gerschewski et al., 2015; Zhou et al., 2010; Zhou et al., 2007). In this context, BGFs’ international entrepreneurial proclivity and learning orientation are revealed as essential buffering factors (e.g., Gerschewski et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2013; Zhou, 2007).

The major challenges explored in the literature can be categorized into two major groups: firm-level barriers and constraints and location-specific challenges.

Firm-level barriers and constraints

One of the challenges MNEs, while expanding rapidly to international markets, is the geographic scope and cultural distance. However, emerging market multinationals BGFs avoid the instabilities and hazards afflicting a firm with pre-existing knowledge (Jain et al., 2019). Furthermore, BGFs also face the liability of being new, smallness, foreignness, outsidership, and emergingness; these could decrease the chances of VGFs’ post-entry survival (Khan & Lew, 2018).

For instance, Indian BGFs operating in the tech industry are known to lack innovation capabilities due to the negative side of B2B relationships. This dark side manifests itself through three mechanisms (a) concealing actual ownership of the invention, (b) impeding innovation through dominant organizational structures inside MNEs, and (c) institutionalizing these practices within MNEs (Malik et al., 2021a, b). This is premised on the notion that the adverse side effects of (dis) innovation are institutionalized in the corporate system due to neocolonial influences, which trace power inequalities across numerous interfaces (Malik et al., 2021a, b).

Location-specific challenges

For BGFs to ensure consistency in their performance, they are often faced with hurdles such as resource constraints, the dual challenge of institutional difference and liability of newness (McGaughey, 2007), knowledge and skills gaps (Loane & Bell, 2006), and institutional compliance in other economies (Falahat et al. 2017, 2018). This may result in additional issues and challenges during international expansions. In China, for instance, BGFs often encounter risk-related dilemmas when faced with greater international competition. It is suggested that their ability to bear the additional risk and engage in risk-taking may solve competition issues (Huang et al., 2019). Similarly, Buccieri et al. (2019) identify resource scarcity as a critical challenge for Indian new ventures. They suggest that international entrepreneurial culture adoption may be vital in fostering ambidextrous innovation to improve performance.

Jean et al. (2020) emphasized that BGFs often rely on digital platforms for internationalization; however, the risks associated with such platforms are seen to be higher in international markets. For instance, product specificity (vulnerability in international markets, depending on the specifications), foreign market competition (price wars and product qualities), domestic institutional voids (legal and regulatory requirements), and foreign market uncertainty (volatility of customer, product acceptance, market situation) can create failure of a digital platform, and this may limit firms’ internationalization potential. Furthermore, technological uncertainties may develop issues in managing customers in international markets (Zhou et al., 2010).

Future research directions

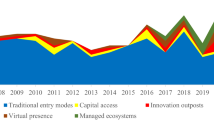

Our analysis reveals that studies exploring the ‘born global’ phenomenon have paid insufficient attention to the contextual specificity of the market(s) in which BGFs operate (e.g., Murmann et al., 2015; Wood et al., 2011) as well as the individual- and firm-level characteristics that could affect internationalization trajectories. Scholars tend to adopt a ‘context-free’ approach or investigate BGFs in broader market contexts, usually for external validity purposes, including a rather diverse group of countries. When investigating the BGF phenomenon in the APAC, scholars often generalize their findings to emerging market countries and/or regions that are similar in terms of their institutional, economic, and societal infrastructures (Falahat et al., 2018; Jain et al., 2019). Rapid economic growth, high market volatility, political instability, and underdeveloped infrastructure are typical characteristics of such markets (Nielsen et al., 2018); the APAC countries, however, do not share these features. The same goes for individual- and firm-level factors, which significantly affect the internationalization of SMEs (e.g., Yang et al., 2020; Agnihotri and Bhattacharya, 2019). As a result, the theoretical and practical implications of such studies are limited; we consequently call for research that would consider the micro-foundations of BGFs internationalization and the macro structures inherent to the region. Table 2 provides a structured summary of the identified research streams and questions. Similarly, the Fig 1 presents summary and future research directions.

Organizational context

Considering the significant impact of top managers’ demographic, experiential, and psychological attributes on the ex-ante decisions and ex-post outcomes of internationalization (Su et al., 2019a, b; Loane et al., 2007; Popli et al., 2022), we encourage further debate and discussion of the role of TMTs in BGFs’ international success. Multilevel analysis is required in order to gain a better understanding of how individual- and group-level factors, such as top managers’ diversity attributes (specifically, cultural diversity), TMT knowledge heterogeneity, and creativity, affect the quality of decisions made in relation to the internationalization process as well as the performance of BGFs operating within the APAC region (e.g., Su et al. 2020). In a similar fashion, firm-level characteristics – in particular, organizational size as a boundary condition – need to be considered for the theorization of BGF internationalization (Child, Karmowska, and Shenkar, 2022).

Moreover, international entrepreneurial culture may be further investigated as a critical driver of creativity, innovation, and enhanced performance of internationalizing SMEs to unveil how incentives to expand into global markets are created within BGFs (Buccieri et al., 2020). Scholars may additionally explore how entrepreneurial culture influences the proclivity for risk-taking, entrepreneurship, and survival in the context of environmental uncertainty and resource scarcity.

Prior studies have also overlooked the role of gender (specifically, the functionality of female-led BGFs) in the internationalization of BGFs from the APAC. While female entrepreneurial responsibilities and activity rates have been increasing (overall), particularly in contexts characterized by low entry barriers, supportive state policies towards entrepreneurship, and a normative entrepreneurship-friendly culture (Hechavarría & Ingram, 2019), it remains unclear how female entrepreneurs identify and exploit opportunities in international markets and deal with problems inherent to (woman) entrepreneurship and rapid internationalization in/from the APAC. International trade enables small enterprises to participate in the global economy, and frequently, such businesses are not successful due to the owners/founders’ background, perception of uncertainty, modes of entrepreneurial behavior and decision-making strategies, and region-specific challenges and barriers. Studies show that the profitability of female-led enterprises may often be lower than those controlled by men (Lee et al., 2016) due to idiosyncratic personality traits (e.g., higher risk-aversion of women), which lead to female entrepreneurs encountering obstacles more frequently than men (e.g., the difficulty of obtaining access to venture capital). Clearly, entrepreneurship is a gendered activity (Eddleston & Powell, 2008; Lee et al., 2016). We call for further in-depth investigations of BGFs led by women.

Institutional context

The more support the government provides to internationalizing firms – for instance, in the form of different local initiatives and outward-looking policies aimed at boosting export-oriented growth, financing, training, technical guidance, etc. – the more likely they are to overcome contextual limitations, acquire foreign market expertise, and improve their international performance (Falahat et al., 2020a, b). Scholars may consider investigating the function of various forms of institutional assistance and engagement in developing BGFs’ internationalization capabilities. Considering the macro structures in the analysis of ACAP BGFs and the role formal and informal institutions play in their rapid/early expansion would contribute significantly to both theory and practice (e.g., Deng et al., 2018).

As our analysis and synthesis of empirical findings demonstrated, BGFs are quite proactive in their global expansion efforts – in particular, they build multilayered partnerships with foreign partners, thus developing networking capabilities that increase the likelihood of survival in the earlier stages of internationalization and help them stay ahead of competition further on (Prashantham et al., 2019a, b). Similarly, the study by Zhou et al. (2010) indicates that network and knowledge capability upgrading are critical mediators of the relationship between international entrepreneurial propensity and firm performance. The authors add that for BGFs, global market expertise, and relationship networks are vital for acquiring the learning benefits of novelty and realizing the potential presented by rapid expansion. Considering the rise in intraregional interdependence and the improvement of intraregional trade in the APAC, scholars should devote more attention to the underlying mechanisms through which BGFs acquire essential relational, social, and human capital and build cross-border networks. The role of institutional context and individual- and firm-level characteristics in transforming networking capabilities to international performance should be explored in greater detail.

Future research may also look into a new emergent mode of entry known as Equity-based, which involves mostly joint ventures and includes both majority and minority forms of partnership, and non-equity-based modes, which include trade partnerships (exporting or sourcing) and contractual relationships such as R&D and marketing contracts (Puthusserry et al., 2018). It would also benefit scholars to investigate which entry modes would be most effective and give the BGFs a competitive edge, especially considering the variety of region-specific challenges such firms may face.

Risk and survival context

When BGFs enter new markets, they face various risks and hurdles, ranging from a lack of market knowledge and information intensity to (potential) cultural maladaptation and severe environmental uncertainty (Zhou et al., 2010). Here, the role of digitalization, digital transformation, and related technological capabilities in ameliorating these risks cannot be underestimated – recent advancements in information technology have significantly altered the functioning of global enterprises (including BGFs), leveling the playing field by providing access to valuable knowledge resources, increasing digital connectivity between stakeholders, reducing the cost of doing business, etc. However, despite the seemingly positive effects of digital transformation, new dangers emerge (Jean et al., 2020). Hence, future research should investigate (on the one hand) which digital solutions – platforms, tools, and technologies – BGFs adopt at different stages of internationalization and (on the other hand) how BGFs engaging in new technology adoption address and overcome the associated digital risks that they face in their global operations.

Another area of future research is the post-entry survival of BGFs in specific institutional contexts. For instance, BGFs from emerging economies are characterized by political instability, currency inconsistency, and lack of access to local funds (Khan & Lew, 2018). This may create a lack of motivation among the BGFs and their survival in other markets (post-entry). Hence, scholars may investigate how BGFs arising from highly underdeveloped entrepreneurial ecosystems, with limited institutional support, navigate the challenges in domestic and international markets and enhance their chances of post-entry survival (e.g., Lee et al., 2020). Similarly, another exploration could manifest the dark sides (such as misconduct, tax evasion, corruption etc.) in the BGF’s internationalization (Malik et al., 2021a, b) and how it may affect their survival in other markets. Moreover, whether dark sides are a deliberate move or forced victimization could be investigated.

Theoretical and practical implications

Our study addresses an essential issue of accelerated internationalization of BGFs in the context of APAC. Prior research has primarily focused on the incremental international expansion of MNEs from/to emerging economies (e.g., Bai et al., 2021). Our findings help fill the gap by considering BGFs from/in the APAC region. The outcomes of this study may guide managers in identifying significant critical challenges and success factors required for their survival and growth. While our findings raise awareness of the importance of the region-specific peculiarities in BGFs’ internationalization process, we also argue that in-depth context-focused investigations should be conducted to enhance scholarly understanding of the institutional effects shaping the BGFs’ actions and entrepreneurial capabilities.

Our findings add to Lahiri et al. (2020) by delving into the context-specific role of BGFs and their internationalization process, encompassing challenges and success factors. For example, managers and institutions of BGFs originating in the APAC and functioning in other geographical regions may find our study helpful because we illustrate the problems, success factors, and possible topics to explore in the future. Because several studies have been published on the APAC region, the limited understanding has been expanded by combining the results of this research. Consequently, it is vital to understand BGFs’ specific organizational characteristics, their inclination for creativity, and strategic activities. Our findings and the framework provided will assist rising BGF entrepreneurs and managers in carefully operating globally and anticipating and overcoming problems from the start of their expansion.

Our study has implications for the institution- and knowledge-based views and organizational learning and legitimacy theories, which build a theoretical foundation for an in-depth exploration of the BGF internationalization in varying country/market contexts. This review is unique in a way that it is the first to focus on the APAC region in the investigation of BGFs; it also provides valuable recommendations for BGFs’ strategic development, which may address the region’s economic concerns in relation to the institutional support provided to firms, availability and access to critical information and resources, collaboration with multiple international partners by understanding and managing the cultural expectations.

Our study has implications for the future of BGF operations, which may shift based on technological disruption. For instance, rapid and proactive worldwide development via digital platforms, such as e-commerce platforms, social networks, and digital media, is one of the most notable transitions in BGFs (Etemad, 2022; Paul & Rosado-Serrano, 2019). In this context, Born Global Firms may now face a drastic shift due to the disruption caused by the ongoing digital technologies and digital laws (e.g., GDPR of Europe) and digital risk (Jean et al., 2020). This implies that BGFs in the Asia Pacific must remain vigilant and look to re-organizing their business model and structures in the country that can expand and be competitive –with the support of technologies. For instance, decentralizing operations and business activities through online and digital modes may reduce the cost and time for BGFs (Oliva et al., 2022; Nemkova, 2017).

Conclusion & Limitations

This research aimed to compile the existing literature on Born Global Firms (BGFs), particularly emphasizing the APAC area. By employing a systematic review and synthesis, this study has investigated and revealed the challenges and success factors of BGFs in the APAC region. The literature from 1994 to 2022 has shown many exciting patterns that APAC BGFs undergo in their internationalization process. In contrast, by identifying the barriers BGFs from the APAC face, we also reveal some critical variables that would help scholars shape future studies more contextually. We did not, however, consider market entry mode in our assessment, which is a limitation in light of our recommendations for further research. Additionally, certain determinants of the success of BGFs in the APAC may have been overlooked due to our consideration of specific academic journals (ABS 4*, 4, and 3) and limiting our sample to (exclusively) peer-reviewed publications. Future research may benefit from supplementing this study by leveraging additional databases (Web of Science, Google Scholar, etc.) and integrating other publications to uncover additional insights.

Change history

13 September 2023

The original version of this paper was updated to change the biography of the 3rd author, Louisa Selivanovskikh.

Notes

The Asia-Pacific region is extensive, reaching northward to Mongolia, southward to New Zealand, eastward to Oceania’s island republics, and westward to Pakistan.

The entry modalities used by the BGFs also define their success. BGFs adopt equity-based collaborative entry mechanisms in joint ventures or partnerships, enhancing expansion operations into overseas markets (Puthusserry et al., 2017). Additionally, the success of newcomers will depend on their ability to address high entry barriers by taking advantage of the more prominent players’ supply chains network (Terjesen, O’Gorman, and Acs, 2008).

References

Agnihotri, A., & Bhattacharya, S. (2019). CEO narcissism and internationalization by indian firms. Management International Review, 59(6), 889–918.

Arte, P. (2017). Role of experience and knowledge in early internationalisation of indian new ventures: A comparative case study. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research, 23(6), 850–865.

Bai, W., Holmström Lind, C., & Johanson, M. (2016). The performance of international returnee ventures: The role of networking capability and the usefulness of international business knowledge. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 28(9–10), 657–680.

Bai, W., Johanson, M., & Martín Martín, O. (2017). Knowledge and internationalization of returnee entrepreneurial firms. International Business Review, 26(4), 652–665.

Bai, W., Johanson, M., Oliveira, L., & Ratajczak-Mrozek, M. (2021). The role of business and social networks in the effectual internationalization: Insights from emerging market SMEs. Journal of Business Research, 129, 96–109.

Bai, W., Liu, R., & Zhou, L. (2020). Enhancing the learning advantages of newness: The role of internal social capital in the international performance of young entrepreneurial firms. Journal of International Management, 26(2), 100733.

Buccieri, D., Javalgi, R. G., & Cavusgil, E. (2020). International new venture performance: Role of international entrepreneurial culture, ambidextrous innovation, and dynamic marketing capabilities. International Business Review, 29(2), 101639.

Buccieri, D., Javalgi, R. G., & Jancenelle, V. E. (2021). Dynamic capabilities and performance of emerging market international new ventures: Does international entrepreneurial culture matter? International Small Business Journal, 39(5), 474–499.

Budhwar, P., Pereira, V., Mellahi, K., & Singh, S. K. (2019). The state of HRM in the Middle East: Challenges and future research agenda. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 36(4), 905–933.

Cavusgil, S. T., & Knight, G. (2015). The born global firm: An entrepreneurial and capabilities perspective on early and rapid internationalization. Journal of international business studies, 46(1), 3–16.

Chandra, Y., Styles, C., & Wilkinson, I. F. (2012). Internationalization.

Chetty, S., & Campbell-Hunt, C. (2004). A Strategic Approach to internationalization: A traditional Versus a “Born-Global” Approach. Journal of International Marketing, 12(1), 57–81.

Child, J., Karmowska, J., & Shenkar, O. (2022). The role of context in SME internationalization–A review. Journal of World Business, 57(1), 101267.

Ciravegna, L., Majano, S. B., & Zhan, G. (2014). The inception of internationalization of small and medium enterprises: The role of activeness and networks. Journal of Business Research, 67(6), 1081–1089.

Danik, L., & Kowalik, I. (2013). The st dies on born global companies-a review of research methods. Journal of Economics & Management, 13, 9–26.

De Clercq, D., & Zhou, L. (2014). Entrepreneurial strategic posture and performance in foreign markets: The critical role of international learning effort. Journal of International Marketing, 22(2), 47–67.

Deng, Z., Jean, R. J., “Bryan, & Sinkovics, R. R. (2018). Rapid expansion of international new ventures across institutional distance. Journal of International Business Studies, 49(8), 1010–1032.

Dzikowski, P. (2018). A bibliometric analysis of born global firms. Journal of Business Research, 85, 281–294.

Eddleston, K. A., & Powell, G. N. (2008). The role of gender identity in explaining sex differences in business owners' career satisfier preferences. Journal of Business Venturing, 23(2), 244–256.

Elbanna, S., Hsieh, L., & Child, J. (2020). Contextualizing internationalization decision-making research in SMEs: Towards an integration of existing studies. European Management Review, 17(2), 573–591.

Etemad, H. (2022). The emergence of international small digital ventures (ISDVs): Reaching beyond born globals and INVs. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 20(1), 1–28.

Falahat, M., Knight, G., & Alon, I. (2018). Orientations and capabilities of born global firms from emerging markets. International Marketing Review, 35(6), 936–957.

Falahat, M., Lee, Y. Y., Ramayah, T., & Soto-Acosta, P. (2020a). Modelling the effects of institutional support and international knowledge on competitive capabilities and international performance: Evidence from an emerging economy. Journal of International Management, 26(4), 100779.

Falahat, M., Lee, Y. Y., Ramayah, T., & Soto-Acosta, P. (2020b). Modelling the effects of institutional support and international knowledge on competitive capabilities and international performance: Evidence from an emerging economy. Journal of International Management, 26(4), 100779.

Falahat, M., & Migin, M. W. (2017). Export performance of international new ventures in emerging market. International Journal of Business and Globalisation, 19(1), 111–125.

Gassmann, O., & Keupp, M. M. (2007). The competitive advantage of early and rapidly internationalizing SMEs in the biotechnology industry: A knowledge-based view. Journal of World Business, 42(3), 350–366.

Gerschewski, S., Lew, Y. K., Khan, Z., & Park, B. I. (2018). Post-entry performance of international new ventures: The mediating role of learning orientation. International Small Business Journal, 36(7), 807–828.

Gerschewski, S., Rose, E. L., & Lindsay, V. J. (2015). Understanding the drivers of international performance for born global firms: An integrated perspective. Journal of World Business, 50(3), 558–575.

Gerschewski, S., & Xiao, S. S. (2015). Beyond financial indicators: AN assessment of the measurement of performance for international new ventures. International Business Review, 24(4), 615–629.

Gilson, L. L., & Goldberg, C. B. (Eds.). (2015). Editors’ comment: so, what is a conceptual paper?. Group & Organization Management, 40(2), 127–130.

González, C., & González-Galindo, A. (2022). The institutional context as a source of heterogeneity in family firm internationalization strategies: A comparison between US and emerging market family firms. International Business Review, 31(4), 101972.

Guo, B., & Wang, Z. (2021). Internationalisation path heterogeneity and growth for international new ventures. International Small Business Journal, 39(6), 554–575.

Hechavarría, D. M., & Ingram, A. E. (2019). Entrepreneurial ecosystem conditions and gendered national-level entrepreneurial activity: A 14-year panel study of GEM. Small Business Economics, 53(2), 431–458.

Hennart, J. F., Majocchi, A., & Hagen, B. (2021). What’s so special about born globals, their entrepreneurs or their business model? Journal of International Business Studies, 52(9), 1665–1694.

Huang, J., Liu, L., & Lu, R. (2019). Industry risk-taking and risk-taking strategy of born-global firms: An empirical study based on the industrial variety perspective. Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration.

Hull, C. E., Tang, Z., Tang, J., & Yang, J. (2020). Information diversity and innovation for born-globals. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 37(4), 1039–1060.

Jain, N. K., Pangarkar, N., Yuan, L., & Kumar, V. (2019). Rapid internationalization of emerging market firms—the role of geographic diversity and added cultural distance. International Business Review, 28(6), 101590.

Jean, R. J., Kim, D., & Cavusgil, E. (2020). Antecedents and outcomes of digital platform risk for international new ventures’ internationalization. Journal of World Business, 55(1), 101021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2019.101021.

Kahiya, E. T. (2020). Context in international business: Entrepreneurial internationalization from a distant small open economy. International Business Review, 29(1), 101621.

Khan, Z., & Lew, Y. K. (2018). Post-entry survival of developing economy international new ventures: A dynamic capability perspective. International Business Review, 27(1), 149–160.

Khavul, S., Peterson, M., Mullens, D., & Rasheed, A. A. (2010b). Going global with innovations from emerging economies: Investment in customer support capabilities pays off. Journal of International Marketing, 18(4), 22–42.

Khavul, S., Prater, E., & Swafford, P. M. (2012). International responsiveness of entrepreneurial new ventures from three leading emerging economies. International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 32(10), 1147–1177.

Khavul, S., Pérez-Nordtvedt, L., & Wood, E. (2010a). Organizational entrainment and international new ventures from emerging markets. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(1), 104–119.

Knight, G. A., & Cavusgil, S. T. (2005). A taxonomy of born-global firms (pp. 15–35). MIR: Management International Review.

Knight, G. A., & Liesch, P. W. (2016). Internationalization: From incremental to born global. Journal of World Business, 51(1), 93–102.

Kumar, N., & Sharma, D. D. (2018). The role of organisational culture in the internationalisation of new ventures. International Marketing Review, 35(5), 806–832.

Lee, I. H., Paik, Y., & Uygur, U. (2016). Does gender matter in the Export performance of International New Ventures? Mediat on Effects of firm-specific and country-specific advantages. Journal of International Management, 22(4), 365–379.

Lee, J. Y., Jiménez, A., & Devinney, T. M. (2020). Learning in SME internationalization: A new perspective on learning from success versus failure. Management International Review, 60(4), 485–513.

Liou, R. S., & Rao-Nicholson, R. (2019). Age matters: The contingency of economic distance and economic freedom in emerging market firm’s cross-border M&A performance. Management International Review, 59, 355–386.

Li, Q., & Deng, P. (2017). From international new ventures to MNCs: Crossing the chasm effect on internationalization paths. Journal of Business Research, 70, 92–100.

Li, Y., Zhang, Y. A., & Shi, W. (2020). Navigating geographic and cultural distances in international expansion: The paradoxical roles of firm size, age, and ownership. Strategic Management Journal, 41(5), 921–949.

Loane, S., & Bell, J. (2006). Rapid internationalization among entrepreneurial firms in Australia, Canada, Ireland, and New Zealand: An extension to the network approach. International Marketing Review, 23(5), 467–485.

Loane, S., Bell, J. D., & McNaughton, R. (2007). A cross-national study on the impact of management teams on the rapid internationalization of small firms. Journal of World Business, 42(4), 489–504.

Luo, Y., & Tung, R. L. (2018). A general theory of springboard MNEs. Journal of International Business Studies, 49, 129–152.

Malik, A., Mahadevan, J., Sharma, P., & Nguyen, T. M. (2021a). Masking, claiming and preventing innovation in cross-border B2B relationships: Neo-colonial frameworks of power in global IT industry. Journal of Business Research, 132, 327–339.

Malik, A., Mahadevan, J., Sharma, P., & Nguyen, T. M. (2021b). Masking, claiming and preventing innovation in cross-border B2B relationships: Neo-colonial frameworks of power in global IT industry. Journal of Business Research, 132(July 2020), 327–339.

McDougall, P. P., Shane, S., & Oviatt, B. M. (1994). Explaining the formation of international new ventures: The limits of theories from international business research. Journal of Business Venturing, 9(6), 469–487.

McGaughey, S. L. (2007). Hidden ties in international new venturing: The case of portfolio entrepreneurship. Journal of World Business, 42(3), 307–321.

Morris, S., Snell, S., & Björkman, I. (2016). An architectural framework for global talent management. Journal of International Business Studies, 47, 723–747.

Mort, G. S., Weerawardena, J., & Liesch, P. (2012). Advancing entrepreneurial marketing: Evidence from born global firms. European Journal of Marketing, 46(3–4), 542–561.

Mukherjee, D., Makarius, E. E., & Stevens, C. E. (2021). A reputation transfer perspective on the internationalization of emerging market firms. Journal of Business Research, 123, 568–579.

Murmann, J. P., Ozdemir, S. Z., & Sardana, D. (2015). The role of home country demand in the internationalization of new ventures. Research Policy, 44(6), 1207–1225.

Nemkova, E. (2017). The impact of agility on the market performance of born-global firms: An exploratory study of the ‘Tech city’innovation cluster. Journal of Business Research, 80, 257–265.

Nielsen, U. B., Hannibal, M., & Larsen, N. N. (2018). Reviewing emerging markets: Context, concepts and future research. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 13(6), 1679–1698.

Nuruzzaman, N., Singh, D., & Gaur, A. S. (2020). Institutional support, hazards, and internationalization of emerging market firms. Global Strategy Journal, 10(2), 361–385.

Oliva, F. L., Teberga, P. M. F., Testi, L. I. O., Kotabe, M., Giudice, D., Kelle, M., P., & Cunha, M. P. (2022). Risks and critical success factors in the internationalization of born global startups of industry 4.0: A social, environmental, economic, and institutional analysis. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 175, 121346.

Paul, J., & Dikova, D. (2016). The internationalization of asian firms: An overview and research agenda. Journal of East-West Business, 22(4), 237–241.

Paul, J., & Rosado-Serrano, A. (2019). Gradual internationalization vs born-global/international new venture models: A review and research agenda. International Marketing Review, 36(6), 830–858.

Pellegrino, J. M., & McNaughton, R. B. (2015). The co-evolution of Learning and Internationalization Strategy in International New Ventures. Manage ent International Review, 55(4), 457–483.

Pellegrino, J. M., & McNaughton, R. B. (2017). Beyond learning by experience: The use of alternative learning processes by incrementally and rapidly internationalizing SMEs. International Business Review, 26(4), 614–627.

Popli, M., Ahsan, F. M., & Mukherjee, D. (2022). Upper echelons and firm internationalization: A critical review and future directions. Journal of Business Research, 152, 505–521.

Prashantham, S., & Birkinshaw, J. (2015). Choose your friends carefully: Home-Country Ties and New Venture internationalization. Manage ent International Review, 55(2), 207–234.

Prashantham, S., Kumar, K., & Bhattacharyya, S. (2019a). International new ventures from emerging economies: Network connectivity and legitimacy building. Manage ent and Organization Review, 15(3), 615–641.

Prashantham, S., Kumar, K., & Bhattacharyya, S. (2019b). International New Ventures from emerging economies: Network Connectivity and Legitimacy Building. Management and Organization Review, 15(3), 615–641.

Puthusserry, P. N., Khan, Z., & Rodgers, P. (2018). International new ventures market expansion through collaborative entry modes: A study of the experience of indian and british ICT firms. International Marketing Review, 35(6), 890–913.

Puthusserry, P. N., Khan, Z., & Rodgers, P. (2018). International new ventures market expansion through collaborative entry modes: A study of the experience of Indian and British ICT firms. International Marketing Review, 35(6), 890–913.

Rasmussan, E. S., Madsen, K., T., & Evangelista, F. (2001). The founding of the Born Global company in Denmark and Australia: Sensemaking and networking. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 13(3), 75–107.

Rui, H., Cuervo-Cazurra, A., & Un, C. A. (2016). Learning-by-doing in emerging market multinationals: Integration, trial and error, repetition, and extension. Journal of World Business, 51(5), 686–699.

Shams, S. R., Vrontis, D., & Christofi, M. (2022). Stakeholder causal scope analysis–centered big data management for sustainable tourism. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 46(5), 972–978.

Snyder, H. (2019). Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research, 104, 333–339.

Su, F., Khan, Z., Kyu Lew, Y., Il Park, B., & Shafi Choksy, U. (2020). Internationalization of Chinese SMEs: The role of networks and global value chains. BRQ Business Research Quarterly, 23(2), 141–158.

Su, N. (2013). Internationalization strategies of chinese IT service suppliers. MIS Quarterly: Management Information Systems, 37(1), 175–200.

Su, Y., Fan, D., & Rao-Nicholson, R. (2019a). Internationalization of chinese banking and financial institutions: A fuzzy-set analysis of the leader-TMT dynamics. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 30(14), 2137–2165.

Su, Y., Fan, D., & Rao-Nicholson, R. (2019b). Internationalization of chinese banking and financial institutions: A fuzzy-set analysis of the leader-TMT dynamics. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 30(14), 2137–2165.

Tang, Y. K. (2011). The influence of networking on the internationalization of SMEs: Evidence from internationalized chinese firms. International Small Business Journal, 29(4), 374–398.

Tan, H., & Mathews, J. A. (2015). Accelerated internationalization and resource leverage strategizing: The case of chinese wind turbine manufacturers. Journal of World Business, 50(3), 417–427.

Terjesen, S., O’Gorman, C., & Acs, Z. J. (2008). Intermediated mode of internationalization: New software ventures in Ireland and India. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 20(1), 89–109.

Tranfield, D., Denyer, D., & Smart, P. (2003). Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. British Journal of Management, 14(3), 207–222.

Tsai, H. T., & Eisingerich, A. B. (2010). Internationalization strategies of emerging markets firms. California Management Review, 53(1), 114–135.

UNCTAD. (2021). Investment flows to developing Asia defy COVID-19, grow by https://unctad.org/news/investment-flows-developing-asia-defy-covid-19-grow-4

Weerawardena, J., Mort, G. S., Salunke, S., Knight, G., & Liesch, P. W. (2015). The role of the market sub-system and the socio-technical sub-system in innovation and firm performance: A dynamic capabilities approach. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(2), 221–239.

Wood, E., Khavul, S., Perez-Nordtvedt, L., Prakhya, S., Velarde Dabrowski, R., & Zheng, C. (2011). Strategic commitment and timing of internationalization from emerging markets: Evidence from China, India, Mexico, and South Africa. Journal of Small Business Management, 49(2), 252–282.

Yang, X., Li, J., Stanley, L. J., Kellermanns, F. W., & Li, X. (2020). How family firm characteristics affect internationalization of chinese family SMEs. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 37(2), 417–448.

Øyna, S., & Alon, I. (2018). A review of born globals. International Studies of Management & Organization, 48(2), 157–180.

Zhang, M., Sarker, S., & Sarker, S. (2013). Drivers and export performance impacts of IT capability in “born-global” firms: A cross-national study. Information Systems Journal, 23(5), 419–443.

Zhou, L. (2007). The effects of entrepreneurial proclivity and foreign market knowledge on early internationalization. Journal of World Business, 42(3), 281–293.

Zhou, L., Barnes, B. R., & Lu, Y. (2010). Entrepreneurial proclivity, capability upgrading and performance advantage of newness among international new ventures. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(5), 882–905.

Zhou, L., Wu, A., & Barnes, B. R. (2012). The effects of early internationalization on performance outcomes in young international ventures: The mediating role of marketing capabilities. Journal of International Marketing, 20(4), 25–45.

Zhou, L., Wu, W. P., & Luo, X. (2007). Internationalization and the performance of born-global SMEs: The mediating role of social networks. Journal of International Business Studies, 38(4), 673–690.

Zhu, Y., Warner, M., & Sardana, D. (2020). Internationalization and destination selection of emerging market SMEs: Issues and challenges in a conceptual framework. Journal of General Management, 45(4), 206–216.

Zucchella, A. (2021). International entrepreneurship and the internationalization phenomenon: taking stock, looking ahead. International Business Review, 30(2), 101800.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Anand, A., Singh, S.K., Selivanovskikh, L. et al. Exploring the born global firms from the Asia Pacific. Asia Pac J Manag (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-023-09913-5

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-023-09913-5