Abstract

This paper provides a systematic description and analysis of the non-predictive use of the Italian future. Several authors claim that, on this use, the Italian future is an evidential (Squartini 2001, Mari 2010, Eckardt and Beltrama 2019, Frana and Menéndez-Benito 2019). Others argue that the non-predictive future does not directly contribute an evidential signal (e.g., Giannakidou and Mari 2018, Farkas and Ippolito 2022). We side with the evidential camp. From an empirical standpoint, we present the results of a battery of tests that show that the non-predictive future patterns with evidentials cross-linguistically. From a theoretical standpoint, we put forward an analysis that combines a slightly modified version of the proposal for evidentials in Davis et al. (2007) with Schlenker’s (2007) view of expressive content. On this account, the Italian evidential future (i) lowers the quality threshold required to perform a successful speech act (Davis et al. 2007) and (ii) triggers an evidential presupposition relativized to the speaker’s beliefs (modeled after Schlenker’s analysis of expressives). Our treatment of the evidential component as an expressive presupposition opens up a new perspective on the study of evidentiality and highlights the need for further detailed empirical studies exploring the extent to which this perspective is applicable cross-linguistically.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

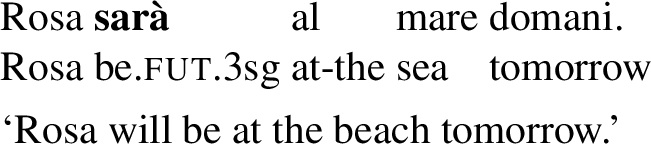

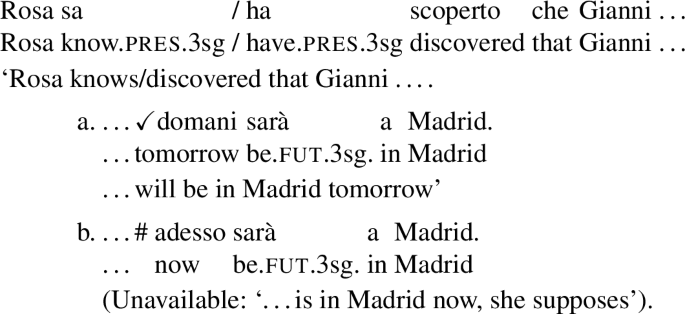

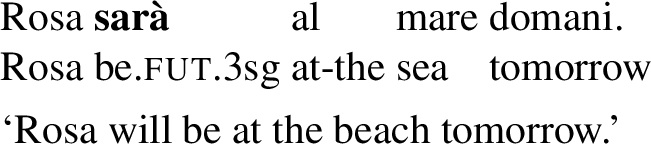

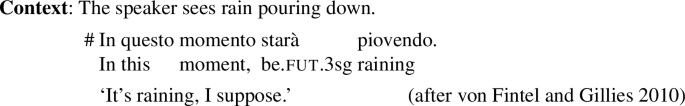

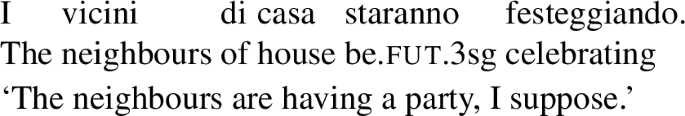

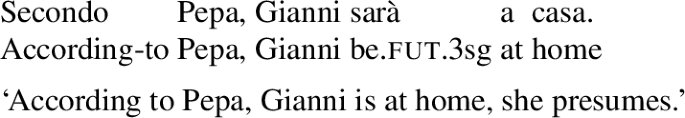

Future morphology in Italian can convey not only predictions about the future (as in (1)), but also hypotheses about the present or the past (see, e.g., Bertinetto 1979, Squartini 2001, Mari 2010): the speaker of (2a) conjectures that Rosa is at the beach at the time of utterance; the speaker of (2b) conjectures that Rosa was at the beach yesterday.

-

(1)

-

(2)

This paper focuses on the use of the Italian future illustrated in (2).Footnote 1 Previous research on this non-predictive use of the future can be divided in two camps. According to one line of research, on this use, the Italian future is an evidential marker (see, e.g., Squartini 2001, Mari 2009, 2010, Eckardt and Beltrama 2019, Frana and Menéndez-Benito 2019). It should be noted that the authors that take the future to be an evidential do not necessarily agree on how the semantic contribution of this item should be formally modelled. For instance, while Mari (2010) treats the Italian future as a modal quantifier, Frana and Menéndez-Benito (2019) argue against a modal analysis for the non-predictive future (but do not provide a full-fledged compositional account).

A second family of accounts argues that the Italian future does not introduce an evidential signal. For example, Giannakidou and Mari (2018), who treat the Italian future (in all of its uses) as an epistemic modal akin to must (see also Giannakidou and Mari 2013), contend that the apparent evidentiality of the future and must arises because these items come with a non-veridicality requirement. Very recently, Farkas and Ippolito (2022) have explicitly argued that the Italian non-predictive future is not an evidential and analyzed it as a special comparative modal with a subjective-likelihood component.

Our contribution to this body of research is twofold. On the empirical side, we present the results of a battery of tests that systematically show that the non-predictive future displays the features that characterize evidentials cross-linguistically. This empirical picture provides support for the view that treats the non-predictive future as an evidential marker. Accordingly, we henceforth refer to this use of the future as ‘evidential future’, abbreviated as EF. However, saying that the EF is an evidential does not in itself commit us to a particular analysis: different views of how evidentials should be modelled are available in the literature and, as noted above, the state of the art on the EF reflects this situation. On the theoretical side, we put forward a non-modal analysis of the EF, which combines a slightly modified version of the proposal for evidentials in Davis et al. (2007) (where evidentials manipulate the quality threshold required to make a successful assertion) with Schlenker’s (2007) view of expressive content.

The discussion proceeds as follows: Sect. 2 shows that the EF patterns with general inferential evidentials across languages. Sections 3 and 4 put forward an analysis of the EF as an evidential marker and show how this analysis accounts for the data presented in Sect. 2. Section 5 compares our proposal with a recent alternative analysis of the EF, that of Farkas and Ippolito (2022). Finally, Sect. 6 briefly concludes and lays out some questions for further research.

2 The future as an evidential marker

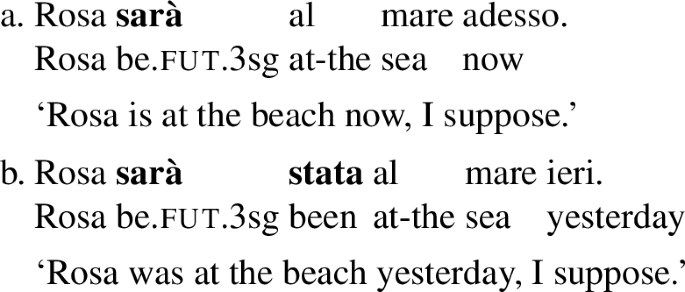

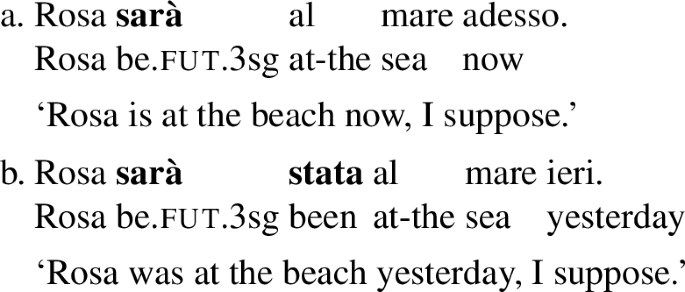

As is well known, evidential markers encode the source of evidence that an individual has for a given proposition. The Cuzco Quechua examples in (3) below illustrate the phenomenon: in these examples, the choice of evidential indicates the type of evidence the speaker has for the proposition that it is raining—direct (e.g., perceptual), reportative or conjectural. We adopt the following (standard) terminology: we call the individual whose evidence is tracked the (evidential) origo (see, e.g., Garrett 2001), and we distinguish between the scope proposition—the proposition that the origo has evidence for—and the evidential proposition (or, alternatively, evidential claim, evidential component)—which conveys the kind of evidence that the origo has (see, e.g., Murray 2017). For example, in (3), the scope proposition is that it is raining, while the evidential proposition is that the origo (the speaker) has direct, reportative, or conjectural evidence that it is raining.

-

(3)

In this section, we argue that the EF should be analyzed as an evidential marker, as it shares the properties that characterize evidentials across languages. First of all, it places constraints on the type of evidence that the origo has for the scope proposition (§2.1). Second, it is obligatorily speaker-oriented in root assertions (§2.2), but hearer-oriented in canonical questions (§2.3). Finally, its evidential component cannot be directly challenged (§2.4) or interpreted in the scope of clause-mate negation (§2.5).

2.1 The future as an inferential evidential

As observed by Mari (2010), the EF is infelicitous when the speaker has direct evidence for the scope proposition. For instance, the EF cannot be used in (4), where the speaker has witnessed the eventuality described by the scope proposition.

-

(4)

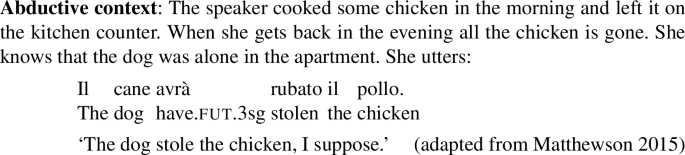

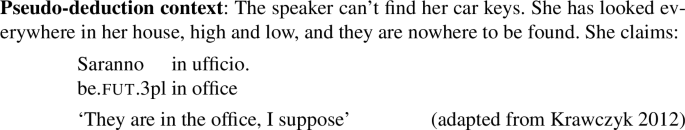

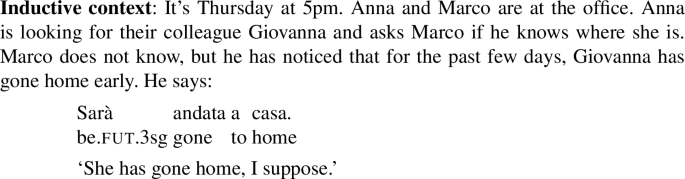

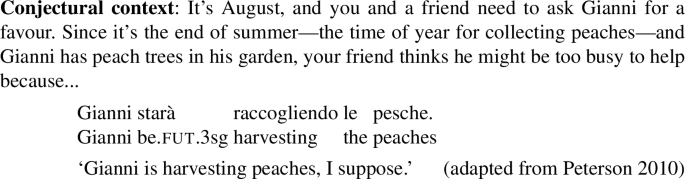

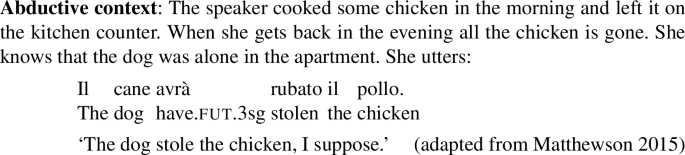

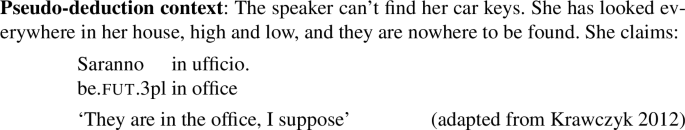

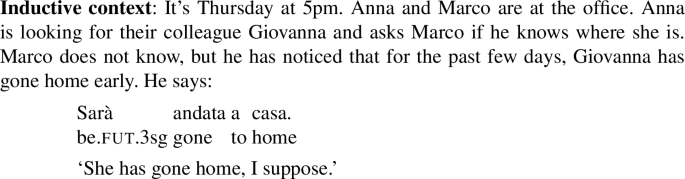

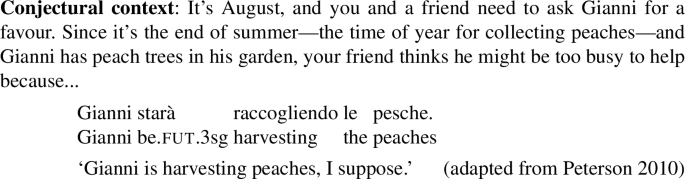

In contrast, the EF is felicitous when the speaker has inferred the scope proposition by means of some reasoning process. The examples below show that the range of inferences that can be expressed with the EF include abductive inferences (roughly, cases where the speaker has some evidence that could be best explained as a result of the scope proposition holding), as in (5), pseudo-deduction (6), inductive reasoning (7), and conjectures/inferences from general reasoning (8).Footnote 2 All the inferences illustrated below involve non-monotonic, defeasible, reasoning (the introduction of new evidence might render the conclusion false). So far, then, the EF fits with general inferential evidentials, corresponding to the inferring branch in Willett’s (1988) evidential typology.

-

(5)

-

(6)

-

(7)

-

(8)

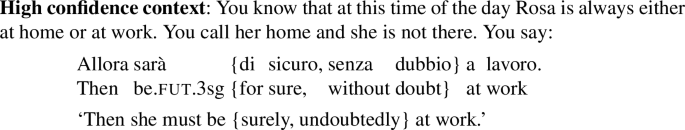

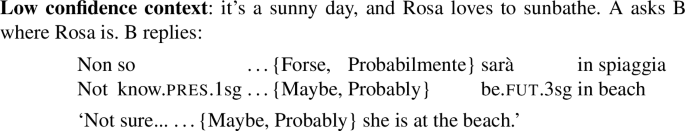

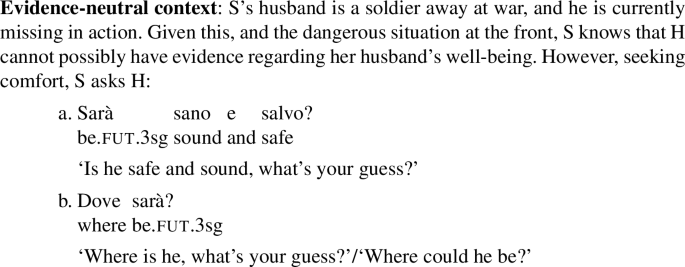

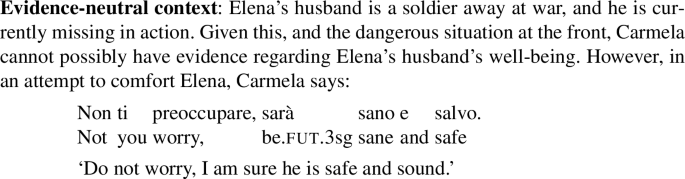

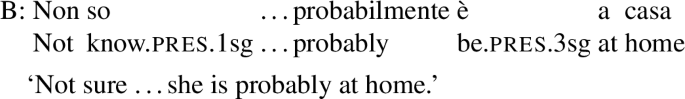

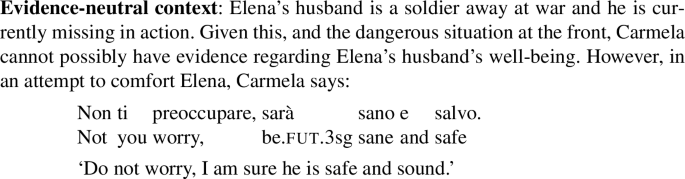

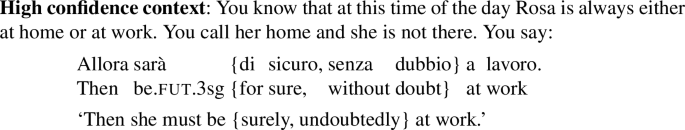

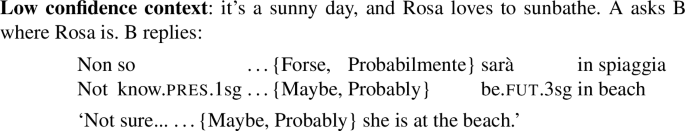

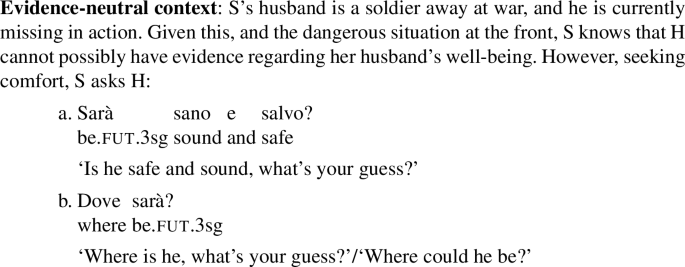

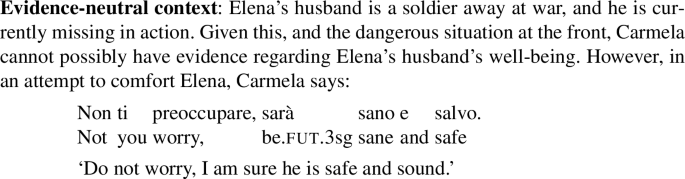

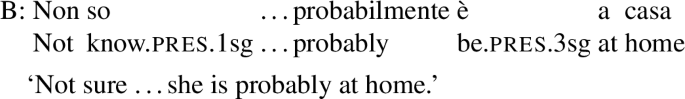

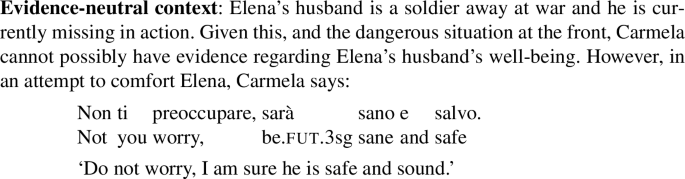

As the reader may have noticed while going through the examples in this section, the inferences conveyed by the EF vary in strength: they range from more solid inferences, which can be reinforced by strong epistemic adverbials (9), to weaker inferences, which are compatible with weaker epistemic adverbials (10) (see Bertinetto 1979 for compatibility of the EF with different types of adverbials).Footnote 3 In (9), the conclusion that Rosa is at home follows from the evidence available to the speaker (but this claim could still be retracted should the speaker learn, e.g., that Rosa’s phone is out of order). In (10), the speaker is advancing a hypothesis about Rosa’s whereabouts that seems reasonable in view of the evidence but does not follow from it. The EF can even be used to advance a conjecture for which the speaker objectively lacks evidence. The example in (11), adapted from Bhadra (2016), illustrates this. (According to Bhadra 2016, these evidence-neutral uses are common for inferential evidentials across languages.)Footnote 4

-

(9)

-

(10)

-

(11)

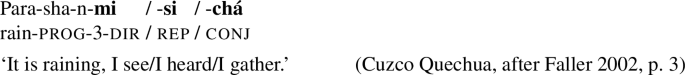

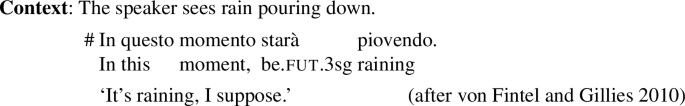

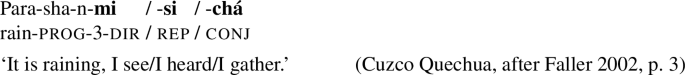

The data presented in this section show that the EF aligns with general inferential evidentials: it is ruled out in cases where the speaker has direct evidence for the scope proposition, but can be used when the speaker has inferred the scope proposition (by means of inferences that range from conjectures to pseudo-deduction), or when the speaker wants to advance a conjecture for which she lacks evidence.Footnote 5 Given this pattern, we formulate the evidential requirement imposed by the EF as a ban on direct evidence, along the lines of what von Fintel and Gillies (2010) propose for epistemic must.Footnote 6 A first version of this requirement, focusing on assertions, is informally stated in (12) (as we will see in §2.2, the origo in root declaratives is always the speaker. Questions will be discussed in §2.3). This formulation will be modified further in Sect. 3.

-

(12)

Evidential requirement of the EF in assertions (provisional): For any context c, an assertion of EF(p) in c is felicitous only if the origo of c (the speaker) has neither direct evidence for p nor for ¬p.

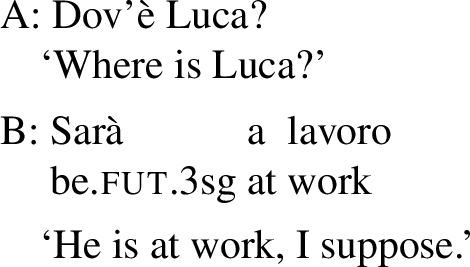

2.2 Speaker-orientation in root declaratives

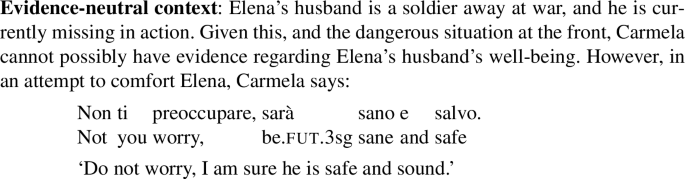

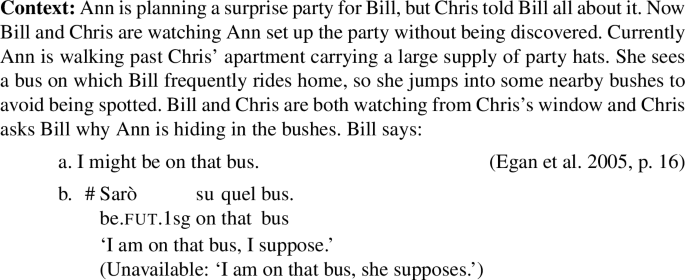

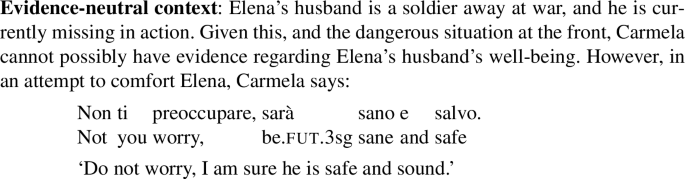

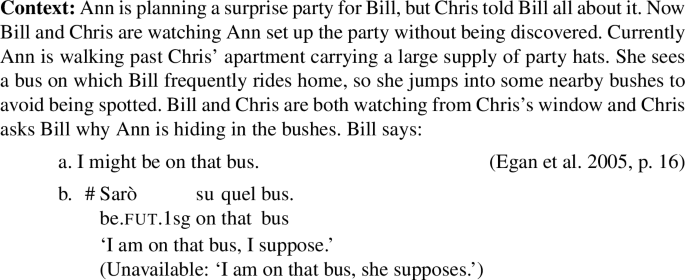

One of the hallmarks of evidentials across languages is that their origo in root declaratives is always the speaker (see Korotkova 2016, a.o.). The EF follows this pattern and it differs in this respect from epistemic modals like must or might. This can be illustrated with the scenarios in (13) and (14), originally designed to show that epistemic modals allow for non-autocentric readings (for discussion, see von Fintel and Gillies 2011; Yanovich 2021, and references therein).

In the scenario in (13), Mordecai can felicitously assert (13a) even if he knows that there aren’t two reds (in von Fintel and Gillies’ (2011) words, “as far as the norms of assertions go, it’s as if he had uttered an explicit claim about Pascal’s evidence” (p. 121). This hearer orientation is not possible for the EF in assertions: in the sentence in (13b), the evidential requirement is necessarily anchored to the speaker. Thus, it would not be felicitous for Mordecai to utter (13b) in the scenario in (13), as, in his position as code-maker, he has direct evidence that there aren’t two reds.

-

(13)

Analogously, in the context in (14), Bill can utter the might statement in (14a) but (should he be speaking Italian), he would not be able to utter (14b), with the EF.

-

(14)

Before closing this section, we would like to highlight the fact that this obligatory speaker-orientation only holds for root declaratives. Although the Italian EF does not embed easily, it can be embedded under some attitude verbs, including (some) verbs of saying like dire (‘say’) or rispondere (‘answer’).Footnote 7

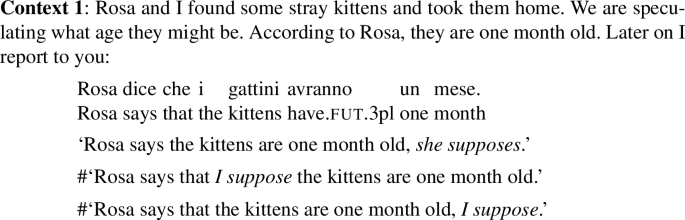

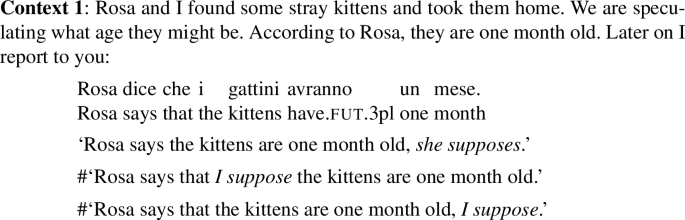

The example in (15), for instance, features an EF embedded under say. When embedded under an attitude, the EF is always anchored to the attitude holder. In (15), for instance, the origo is clearly Rosa, not the speaker: the sentence conveys that Rosa lacks direct evidence for the scope proposition.Footnote 8

-

(15)

This pattern is consistent with the evidential-status of the EF. Languages where evidentials can syntactically embed under (some) attitudes fall into three categories (see Korotkova 2016 for references and discussion): (i) those where evidentials remain speaker-oriented under attitudes (e.g., Georgian), (ii) those where evidentials can optionally shift under attitudes (e.g., Turkish), and (iii) those where evidentials obligatorily shift under attitudes (e.g., Korean). The EF belongs to the third category.

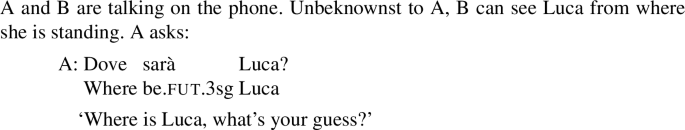

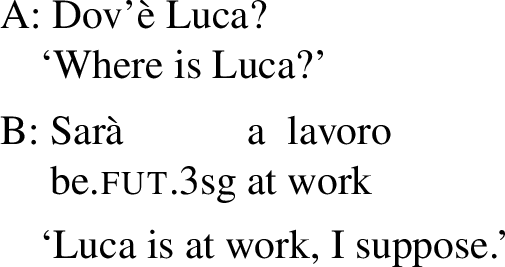

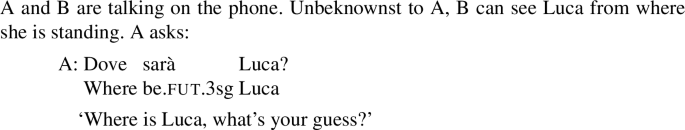

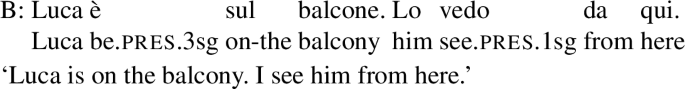

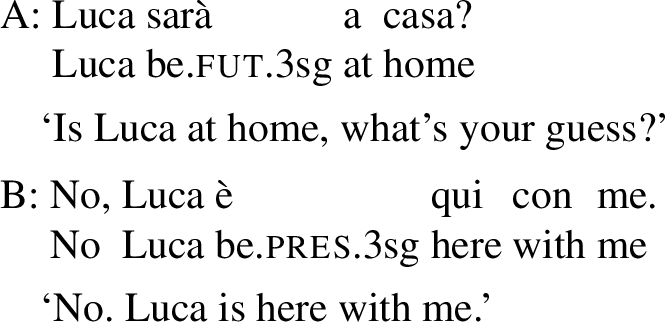

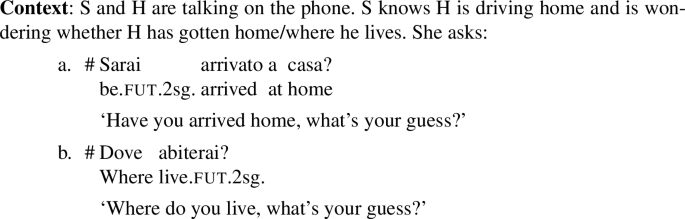

2.3 Interrogative flip in questions

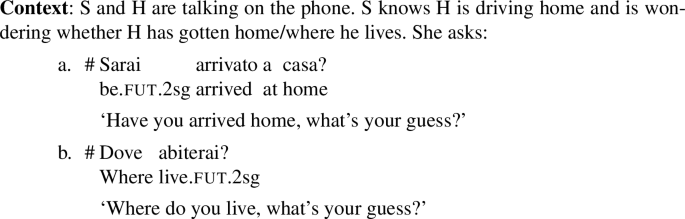

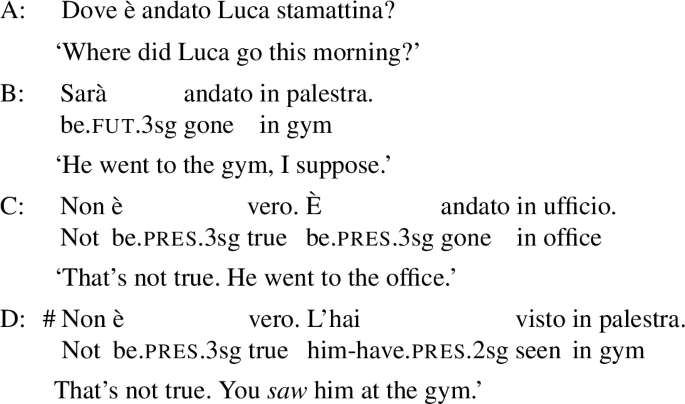

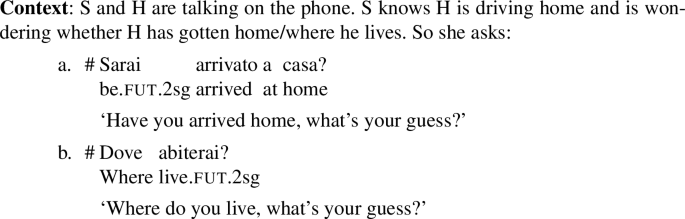

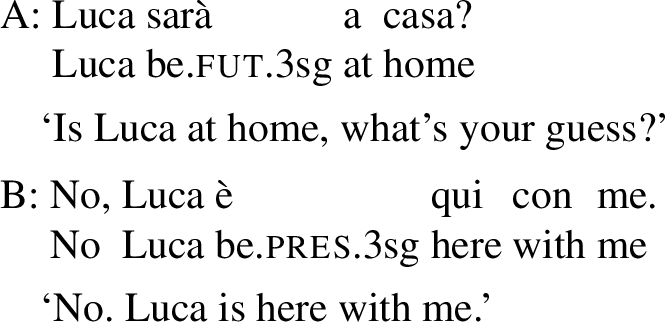

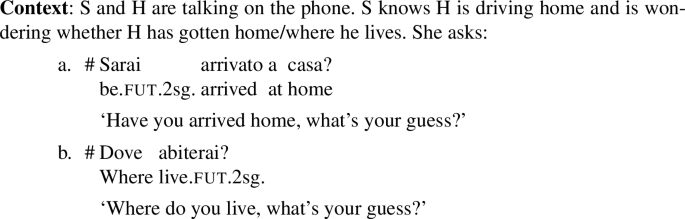

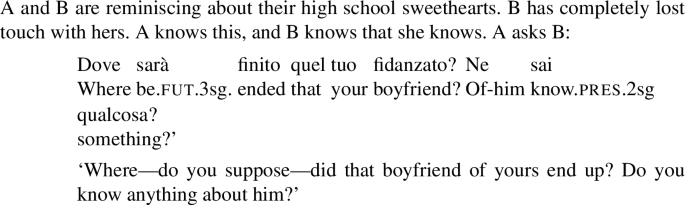

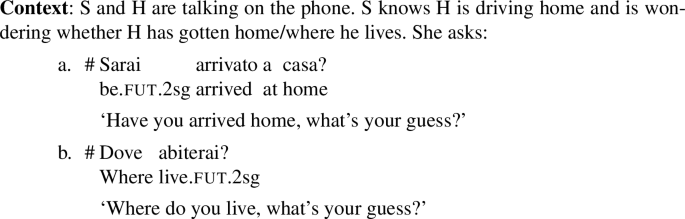

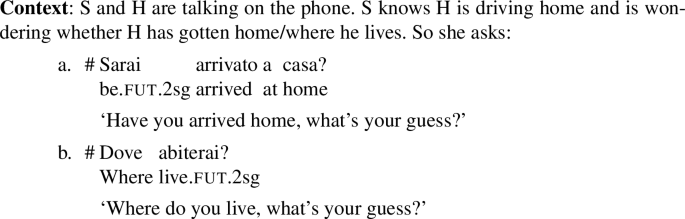

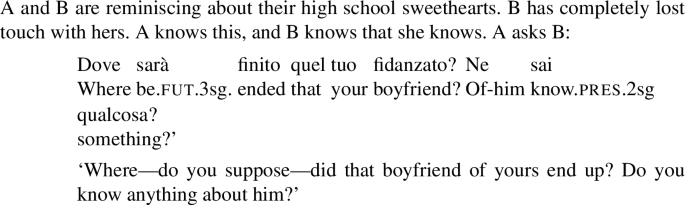

Cross-linguistically, evidentials in information-seeking questions display interrogative flip (Garrett 2001, Speas and Tenny 2003, Murray 2010, a.o.): the origo shifts from the speaker to the addressee. As a result, these questions signal the expected source of evidence for the requested answer. As noted repeatedly in the literature, questions with the EF follow this pattern (see Eckardt and Beltrama 2019, Farkas and Ippolito 2019, Frana and Menéndez-Benito 2019). Canonical (information-seeking) questions with the EF are ruled out in contexts where the hearer is assumed to have direct evidence for the answer: the examples in (16), for instance, are distinctly odd.

-

(16)

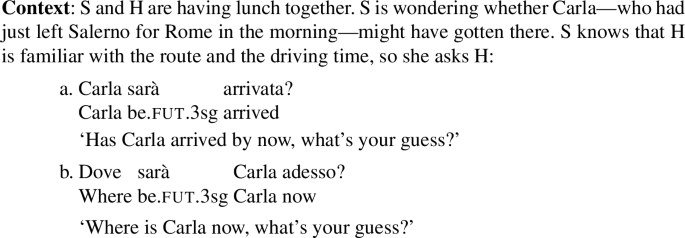

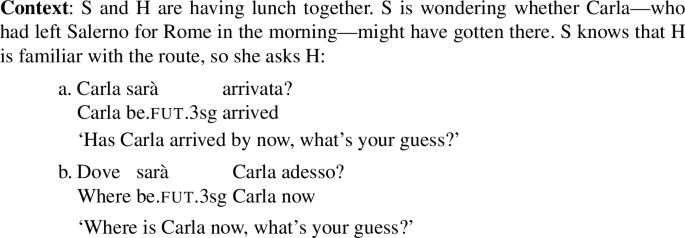

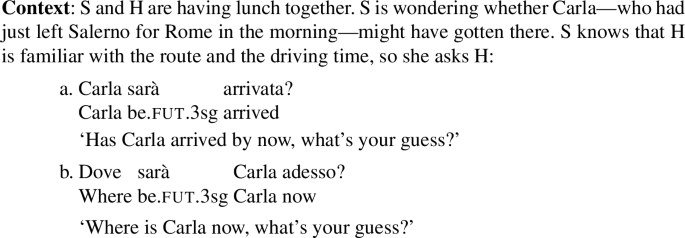

In contrast, the questions in (17), which ask the addressee to draw an inference regarding Carla’s whereabouts, are felicitous.

-

(17)

As in the case of assertions, the degree of confidence that the hearer is expected to have for the answer varies. In (17), the hearer is expected to provide an informed hypothesis, based on his knowledge about the route. In contrast, in (18) (a variation on the soldier scenario in (11)), the speaker knows that the hearer can at best put forward a conjecture.Footnote 9

-

(18)

Thus, it appears that EF-marked questions are flipped versions of the corresponding assertions. We have argued that the EF requires that the origo “lack” direct evidence for the scope proposition. As shown in Sect. 2.1, this evidential requirement is satisfied in a wide range of situations, including those where the origo lacks evidence altogether. In questions, due to interrogative flip, the hearer is expected to lack direct evidence for any of the answers. This includes both cases where the hearer can rely on indirect evidence to advance a possible answer, and cases where the hearer lacks evidence altogether and can only put forward a guess. Given this, we informally state the evidential requirement of the EF in questions (including both polar and content questions) as in (19).

-

(19)

Evidential requirement of the EF in questions (provisional): For any context c, an utterance of EFQ in c is only felicitous if the origo of c (the hearer) does not have direct evidence for any possible answer to Q.Footnote 10

Before closing this section, we would like to highlight that the evidential requirement in (19) may take a different shape in non-canonical questions, such as biased, rhetorical or self-addressed questions (for recent overviews of non-canonical questions see Dayal 2016, Farkas 2020). In this paper, we focus on canonical questions, but we offer some brief remarks on self-addressed questions below (for an analysis of the interaction of the Italian EF with different types of biased questions, see Frana and Menéndez-Benito 2019).

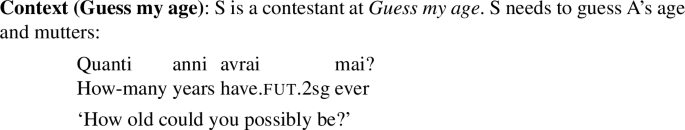

Self-addressed questions can be found in situations where the interlocutor (if there is one present) is assumed to not actively participate in the conversation. Eckardt and Disselkamp (2019) argue that in these kinds of questions, the questioner fulfills the role of the addressee.Footnote 11 Given this, we expect the origo in self-addressed questions with the EF to be the speaker, rather than the hearer. This in turns leads to the prediction that, in self-addressed questions, the evidential requirement will be anchored to the speaker, which is indeed what we find. In (20), the speaker is deliberating with herself (we assume, with Eckardt and Disselkamp 2019, that the second person you in cases like this refers to a ‘bystander’ rather than the addressee). The no direct evidence requirement is thus associated with the speaker, not with the hearer (who is of course expected to have direct evidence regarding her age).

-

(20)

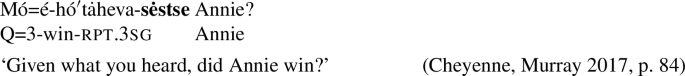

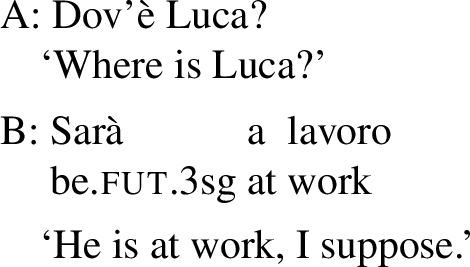

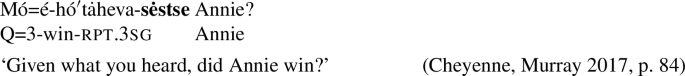

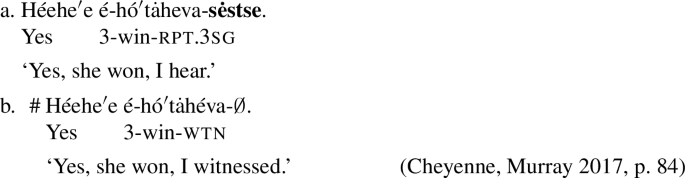

2.4 Non-challengeability of evidential requirement

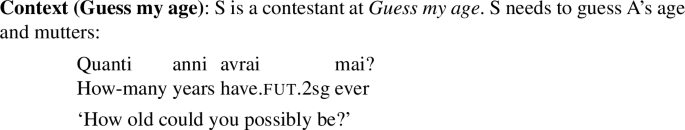

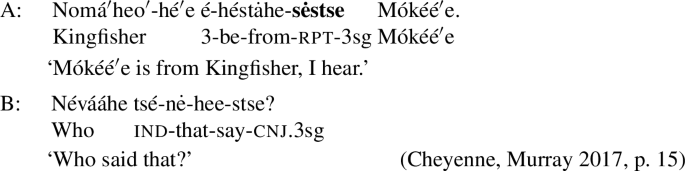

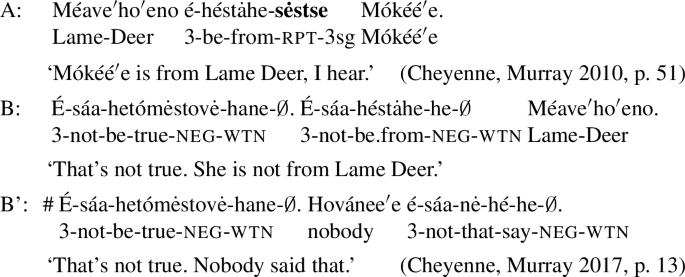

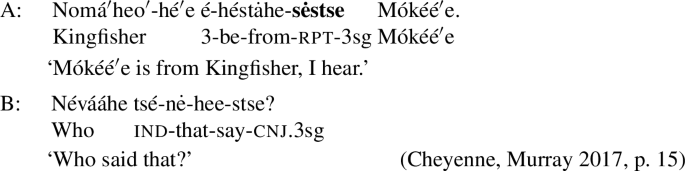

Another cross-linguistically stable property of evidentials is that, while the scope proposition is directly challengeable, the evidential proposition is not (see, e.g., Murray 2017 and references therein). In the Cheyenne example in (21), for instance, B may disagree with the content of the scope proposition but not with the claim that A acquired that content via hearsay.

-

(21)

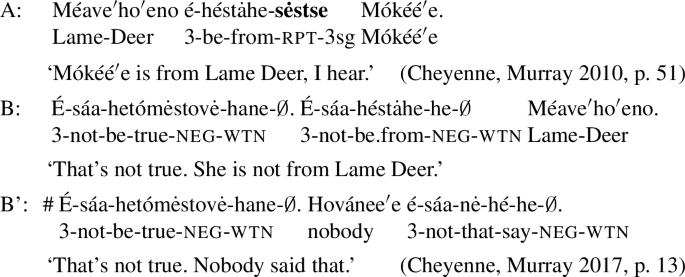

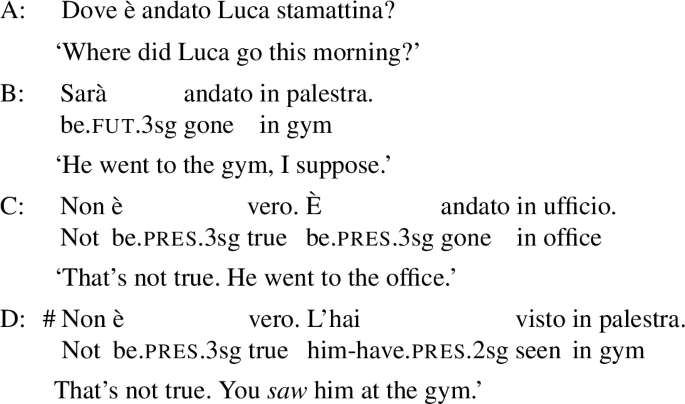

The EF patterns once again with evidentials: in (22), that’s not true can be used to challenge the scope proposition p (that Luca is ill), but not the evidential claim (that the speaker does not have direct evidence that Luca is ill). While C’s response to B’s utterance is felicitous, an attempt to use that’s not true to contest the evidential claim (by stating that B has direct evidence for p), as D does, results in infelicity.

-

(22)

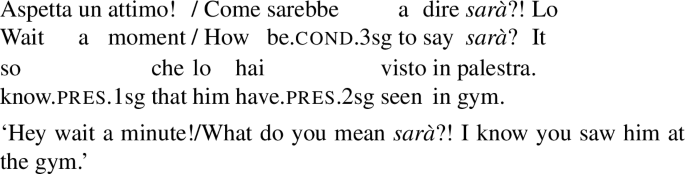

Murray (2017) notes (for Cheyenne) that while the evidential proposition is not directly challengeable, it can be indirectly challenged. She provides the example in (23), where B questions who the source of the report is, and notes that another diagnostic for testing whether content is indirectly challengeable is the ‘Hey, wait a minute’ test (von Fintel 2004).

-

(23)

The EF also fits this pattern. In the example in (22), D could have reacted to B’s assertion with something along the lines of (24).

-

(24)

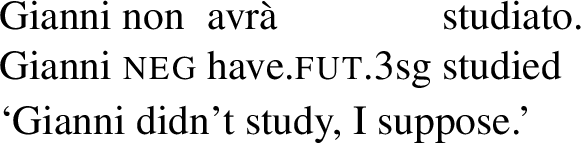

2.5 Interaction with negation

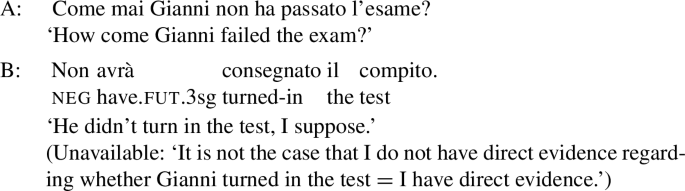

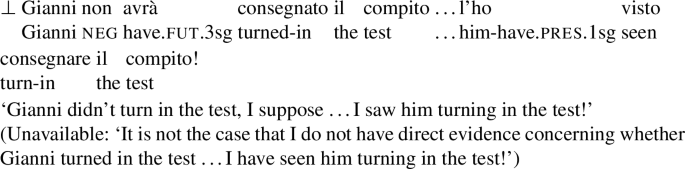

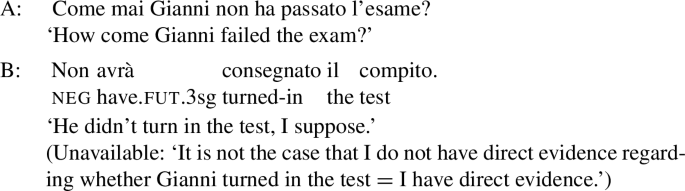

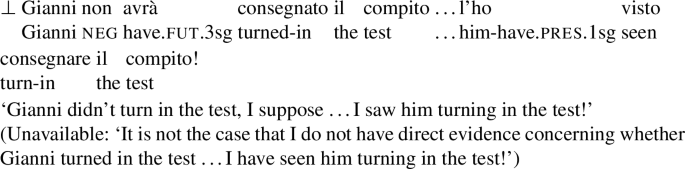

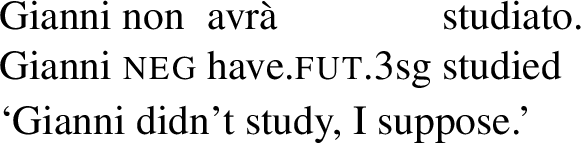

Across languages, the evidential claim is not interpreted in the scope of clause-mate negation: negation targets the scope proposition, not the evidential claim (de Haan 1997, Faller 2002, Matthewson et al. 2007, Murray 2017, a.o.). As noted by Eckardt and Beltrama (2019), the EF follows this pattern. In (25), B replies to A’s question by advancing the hypothesis that Gianni didn’t turn in the test, but she also conveys that she doesn’t have direct evidence to back up her claim. Thus, negation does not affect the evidential claim: the sentence cannot convey that B has direct evidence to back up her claim. Moreover, (26) sounds contradictory in any context.Footnote 12

-

(25)

-

(26)

To sum up, we have seen that the EF shares all the properties that collectively identify the class of evidentials across languages.Footnote 13 In what follows, we put forward a proposal that accounts for the evidential profile of the EF. We proceed in two steps. Section 3 discusses the evidential requirement imposed by the EF. In line with most work on evidentials, we argue that the evidential requirement contributes not-at-issue content. We however depart from previous literature on evidentials in that we analyze this component as an expressive presupposition (as in Schlenker’s 2007 analysis of expressives). Section 4 focuses on the at-issue contribution of sentences with the EF. Based on the differences between the EF and epistemic modals, we take the at-issue component to be unmodalized (see also Murray 2017). This move raises the question of why a speaker that asserts a sentence with the EF does not seem to fully commit to the scope proposition. In order to meet this challenge, we adopt a slightly modified version of the account for evidentials put forward in Davis et al. (2007).

3 Analyzing the EF: The evidential claim

In Sect. 2, we saw that the evidential requirement of the EF can intuitively be formulated as a ban against direct evidence. This section further discusses how this component should be formalized. Section 3.1 argues that the evidential requirement is not-at-issue content: it passes all the tests for not-at-issueness identified in the literature. The remaining sub-sections develop an analysis of this not-at-issue component. In Sect. 3.2, we start by assuming that the evidential requirement is a presupposition, modelled on the presupposition that von Fintel and Gillies (2010) put forward for epistemic must. Section 3.3 discusses an issue for this proposal: the EF is felicitous in contexts where the evidential requirement is not taken for granted. We further show that the profile of the EF in questions is problematic also for alternative accounts where the evidential requirement is treated as new but peripheral content (Murray 2017). Section 3.4 argues that this tension can be solved if the evidential component is treated as an expressive presupposition—a presupposition that is anchored to the speaker’s beliefs (Schlenker 2007).

3.1 The evidential claim is not-at-issue

Almost all analyses of evidentials share the view that the evidential component is not-at-issue content (Faller 2002, 2019, Izvorski 1997, Murray 2010, 2017, among many others).Footnote 14 The evidential requirement of the EF also patterns as not-at-issue with respect to the tests for (not)-at-issueness identified in the literature. The discussion below illustrates this, following the presentation of the diagnostics in Tonhauser 2012.

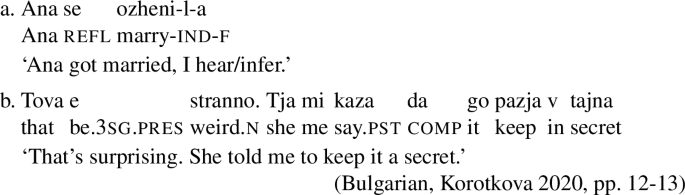

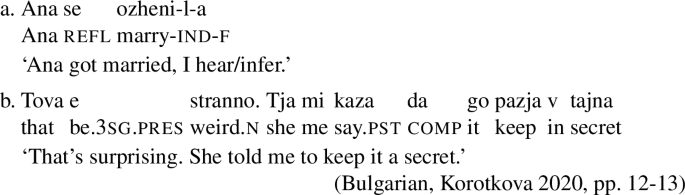

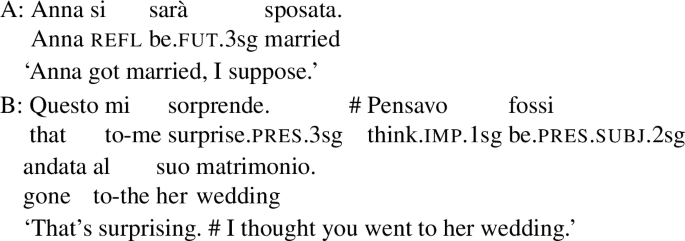

A standard test for (not)-at-issueness rests on the assumption that only at-issue content can be targeted by direct denials such as that’s not true (Diagnostic 1 in Tonhauser 2012). This test has often been applied to evidentials (see e.g., Matthewson et al. 2007, Murray 2010, 2017, Faller 2002, 2019). As we have seen (§2.4), the evidential claim is not directly challengeable, and has accordingly been argued to be non-at-issue. However, Korotkova (2016) doubts the effectiveness of this test for evidentials—she contends that the non-challengeability of the evidential claim is a by-product of subjectivity. Recall that evidentials in root declaratives are always interpreted with respect to the speaker’s evidence (§2.2). Korotkova argues that this evidence is privileged information, not accessible to other speakers, and therefore not challengeable.Footnote 15 In this connection, she notes that that’s not true signals two things: disagreement and that anaphora (see also Korotkova 2020). Anaphoric potential has been argued to correlate with at-issueness (e.g., in Murray 2017). On this view, if the evidential requirement is not-at-issue, it should be inaccessible to that anaphora across the board. Korotkova shows that this is not the case in Bulgarian, where the evidential requirement can be targeted by non-denying anaphora: in her example (27), the surprise is not about Ana’s getting married but about the first speaker having been told about it—the that anaphora picks up the evidential claim. In contrast, it does not seem possible to construct parallel examples with the EF: the attempt in (28), where B makes it clear that she is surprised about A not having direct evidence regarding whether Ana got married, is distinctly odd. Thus, to the extent that that anaphora is indicative of at-issue status (see Snider 2007 for discussion), the evidential requirement of the EF patterns as not-at-issue.

-

(27)

-

(28)

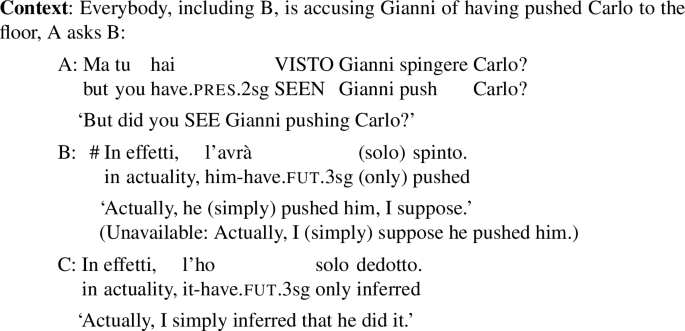

A second test probes for the at-issue status of a proposition by determining whether that proposition can address a Q(uestion) U(nder) D(iscussion) (Diagnostic 2 in Tonhauser 2012). The assumption underlying this diagnostic is that only at-issue content can address a QUD. Work that applies the QUD diagnostic to evidentials includes, e.g., Bary and Maier (2021) for Gitksan, Lee (2011) for Korean and Faller (2019) for Cuzco Quechua. In all of these languages, the evidential claim comes out as not-at-issue with respect to the QUD test.

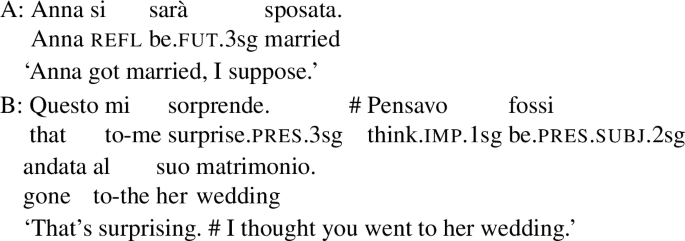

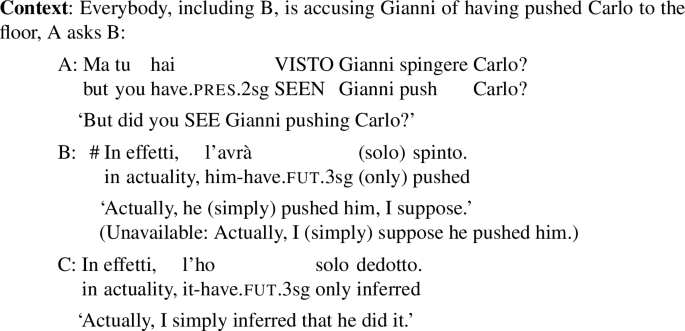

The same holds for the EF, as shown in (29). If the evidential claim associated with B’s reply to A’s question (‘I don’t have direct evidence regarding whether Gianni pushed Carlo’) could address the question posed by A, B’s reply should be as felicitous as C’s. Instead, B’s utterance is odd as an answer to A’s question.

-

(29)

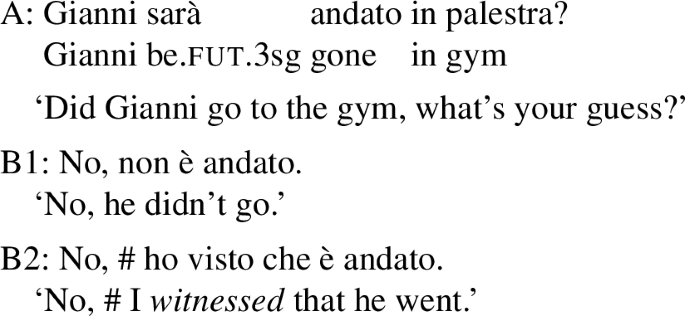

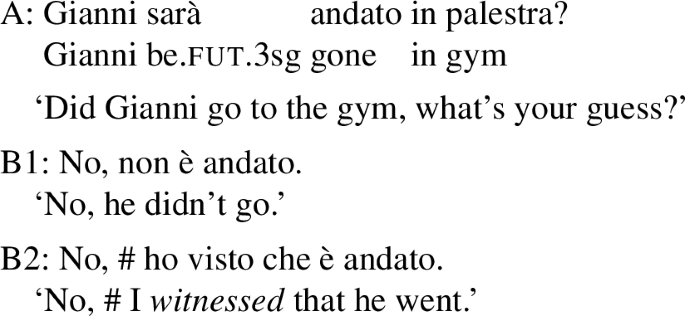

Yet another test for (not)at-issueness is based on the assumption that the set of alternatives corresponding to a question’s possible answers is determined exclusively by the question’s at-issue content. The expectation is that yes/no answers followed by an utterance that confirms or denies the not-at-issue content associated with the question will be infelicitous (Diagnostic 3 in Tonhauser 2012).Footnote 16 The evidential claim of the EF patterns as not-at-issue with respect to this test too. The dialogue in (30) illustrates this for the negative answer: while a no answer that denies that Gianni went to the gym (B1) is felicitous, a no answer that denies the evidential claim (B2) is not. Note that this test is not subject to Korotkova’s criticism for the challengeability test, as B should be able to access her own evidence.

-

(30)

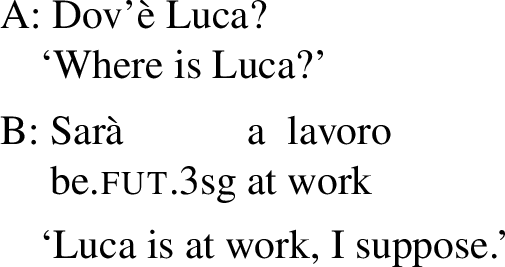

3.2 The evidential claim as a presupposition, first try

We have argued that the evidential requirement of the EF is not-at-issue. But what kind of not-at issue content does this requirement contribute? In Sect. 2.1, we characterized it as a ban against direct evidence, following von Fintel and Gillies (2010) on epistemic must. According to von Fintel and Gillies (2010), must triggers a presupposition that neither the prejacent nor its negation are known through what they call ‘privileged information’ (direct/trustworthy evidence; in their terms, “the privileged information does not directly settle the question of the prejacent”, p. 369). We begin by adopting a modified version of this formulation, as in (31).Footnote 17

-

(31)

\([\!\![EF [p] ]\!\!]^{c}\) is only defined when the origo of c has neither direct evidence for p nor for ¬p

Before we continue, a quick note on origo shift is in order. As we have seen, the EF displays interrogative flip (at least in canonical questions): the origo of c is the speaker in assertions of root declaratives (§2.2) and the hearer in questions (§2.3). The question of how to derive interrogative flip for evidentials is still very much under debate. Two major families of approaches can be distinguished: indexical and universal approaches.Footnote 18 Indexical approaches (Murray 2010, Lim and Lee 2012, a.o.) treat evidentials as shiftable indexicals. Very simply put, the core idea is that the origo of c may be interpreted with respect to the utterance context (and thus be resolved as the agent of the utterance, the speaker) or to another relevant context, be it an attitude context (in which case the origo would correspond to the attitude holder), or the answering context (where the origo would correspond to the hearer).

Universal approaches (Speas and Tenny 2003, Mcready and Ogata 2007, a.o.) argue that evidential shift in questions is part of a more general mechanism (semantic or syntactic, depending on the theory) that allows perspective-sensitive expressions to be anchored to the addressee in questions and to the speaker in assertions. Adjudicating between different accounts of interrogative flip is beyond the scope of this paper. In what follows, we simply assume, in line with universal approaches, that the origo of c has a default contextual resolution corresponding to the epistemic authority of the speech act, i.e., the individual who has primary authority over the validity of the proposition expressed by an utterance, be it an assertion (the speaker) or the expected answer to a question (the hearer).

Let us now go back to the presupposition in (31), and assess how it fares with respect to the data presented in Sect. 2. This presupposition is designed to rule out the use of assertions with the EF in scenarios where the origo of c (the speaker) has direct evidence for the scope proposition, but allow it in contexts where the speaker has (only) indirect evidence or lacks evidence altogether (§2.1). Treating the evidential requirement as a presupposition squares well with the observation that this requirement cannot be directly challenged, as discussed in Sect. 2.4. (Note that while non-challengeability is not necessarily indicative of not-at-issueness—see Korotkova 2016—the fact remains that not-at-issue content—including presuppositional material—cannot be directly challenged.) A presuppositional analysis is also consistent with the fact that the evidential requirement cannot be targeted by negation (§2.5). Given (31), we predict this to be the case regardless of whether the EF syntactically scopes above or below negation (see Korotkova 2020 for general discussion of this issue). Consider (32), for instance. This example is predicted to trigger the presupposition that the speaker does not have direct evidence regarding whether Gianni studied, irrespective of whether the EF scopes over non or under non (as in the latter case the presupposition would project out of the scope of negation).

-

(32)

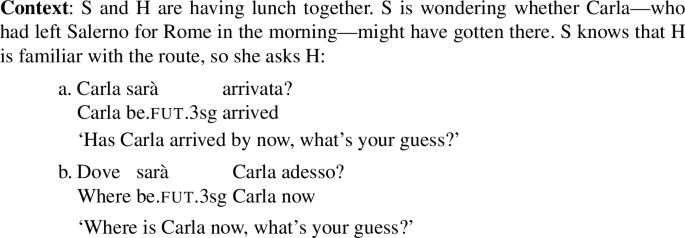

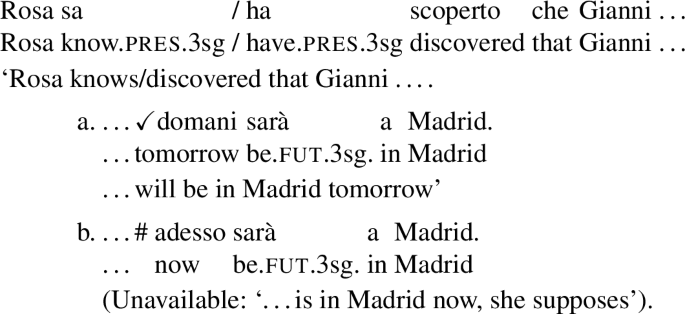

A presuppositional analysis also accounts for the evidential requirement attested in questions. Given well-known facts about presupposition projection and origo shift (interrogative flip), we expect questions with the EF to presuppose that the hearer does not have direct evidence for any possible answer to the question. In polar questions, this presupposition arises through the combination of global projection and the disjunctive form of our evidential requirement. A polar question p? triggers the same presupposition as an assertion of p (e.g., both John is smoking again and Is John smoking again? presuppose that John smoked before). Thus, a polar question of the form EF(p)? will presuppose that the origo (given interrogative flip, the hearer) has neither direct evidence for p (the positive answer) nor for ¬p (the negative answer). Given this, the polar question in (16), repeated in (33a), is predicted to presuppose that the hearer does not have direct evidence regarding whether he has arrived home or not. In content questions, presuppositions have been argued to project universally (see, e.g., Guerzoni 2003, Schlenker 2008). For instance, a question like who among those ten people do you regret inviting? presupposes that you invited each of those ten people. Given universal projection, the content question in (33b) is expected to presuppose that, for any location x, the hearer has neither direct evidence that he lives in x nor that he does not.

-

(33)

Given the presuppositions we derive for the questions in (33a) and (33b), these questions are correctly predicted to be infelicitous in a (normal) context, where the hearer is expected to have direct evidence that bears on the issue of whether he is home/where he lives. In contrast, the questions in (17), repeated below as (34), are expected to be felicitous in the given context, where the hearer does not have direct evidence regarding Carla’s whereabouts.Footnote 19

-

(34)

To sum up, we have assumed that the evidential requirement of the EF is a presupposition anchored to a perspectival center (the origo), which corresponds to the speaker in assertions and the hearer in questions. The content of the presupposition (a ban on direct evidence) is modelled on von Fintel and Gillies’ (2010) analysis of epistemic must. The next two sections are devoted to refining this proposal. Section 3.3 discusses an issue for the claim that the evidential requirement is presuppositional. The data presented in this section will be shown to be problematic also for an account where the evidential requirement contributes new not-at-issue information (Murray 2017). Section 3.4 argues that the problematic examples can be accounted for if the evidential requirement is analyzed as an expressive presupposition (Schlenker 2007).

3.3 An issue for the presuppositional account

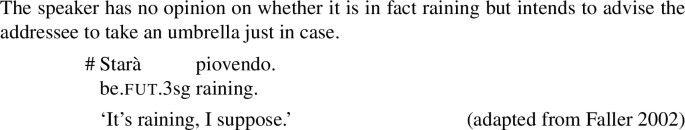

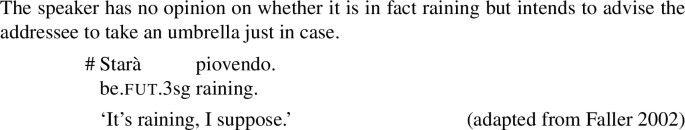

Presuppositional analyses of evidentials (see Izvorski 1997 on the Bulgarian evidential perfect) have been challenged on the grounds that the evidential requirement does not seem to impose a pre-condition on the input context (see, e.g., Faller 2002, Tonhauser 2013, Koev 2017). This objection applies also to the EF: B’s assertion in (35), for instance, is felicitous even if A wrongly assumed that B had direct evidence regarding Luca’s whereabouts.

-

(35)

This intuition might not necessarily be an insurmountable problem for a presuppositional account. Perhaps the evidential requirement is a presupposition, but one that is very easy to accommodate. As Stalnaker (2014) discusses, the fact that the speaker believes a proposition p and takes it to be common ground is often enough for the hearer to come to believe p. Examples like (35) could be amenable to this analysis: B can be assumed to be an authority on her own evidence. Given this, B’s presupposing that she lacks direct evidence regarding the issue that A raises could lead A to unobtrusively revise her beliefs.

An alternative view, put forward by Murray (2017), has it that the evidential claim contributes new, but peripheral information, much like parentheticals do (see Potts 2007a). On Murray’s account, the evidential requirement contributes a non-negotiable update: when a sentence with an evidential is asserted, the content of the evidential claim is automatically added to the common ground (in contrast, the addition of at-issue content is subject to acceptance on the part of the hearer). Adopting this view for the EF would square well with the fact that the evidential requirement does not have to be taken for granted. But note that in order to account for the acceptability of the EF in examples like (35), we would need to propose that the non-negotiable update triggered by B’s assertion automatically leads to a revision of A’s assumptions.Footnote 20

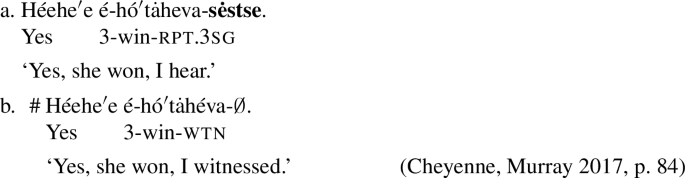

Murray (2017) contends that, while the evidential requirement in Cheyenne is not a presupposition in assertions, it is in questions. In Cheyenne examples like (36), the question requires an input context where it is taken for granted that the hearer has reportative evidence for the answer. According to Murray, this explains why the answer in (37b), with a direct evidential, is odd, whereas an answer with the reportative evidential (37a) is perfectly fine.Footnote 21

-

(36)

-

(37)

The pattern is different for the EF. We can construct examples where the evidential requirement of a question with the EF is not taken for granted, and where the question is nevertheless felicitous. Consider, as an illustration, the dialogue in (38). When A asks her question, B knows that she (B), in fact, has direct evidence regarding Luca’s whereabouts. Thus, prior to A’s question, it was not common ground that B lacked direct evidence regarding Luca’s location. This, however, does not make A’s question infelicitous.

-

(38)

In the context in (38), it is not reasonable to assume that B will come to believe a proposition that contradicts what she knows about her own evidence. Still, revising one’s beliefs is not the only way to accommodate a presupposition. A hearer that believes that a proposition p presupposed by the speaker is false, could still accommodate p, by accepting p for the purposes of the conversation, as long as the issue of whether p is not particularly relevant for the communicative exchange (Stalnaker 2014). So far, then, the example in (38) might still be reconciled with the presuppositional view. However, note that B could answer A’s question with (39) below. B’s assertion in (39) contradicts the assumption that B lacks direct evidence for Luca’s whereabouts and is therefore incompatible with the view that she is entertaining this assumption for the purposes of the conversation.Footnote 22

-

(39)

We have seen that the dialogue in (38)-(39) raises a challenge for the view that the evidential requirement—formulated as in Sect. 3.2—is a presupposition. To this, we add that extending Murray’s view (that the evidential requirement triggers an automatic update) to questions would not help with these examples. On this view, after A’s utterance, the proposition that B does not have direct evidence regarding Luca’s whereabouts would be automatically added to the common ground. But this update would clash with B’s follow-up assertion, and this should presumably give rise to a conversational standstill. This is contrary to fact.

Let us take stock. Taking the evidential requirement to be a presupposition does not seem to be on the right track: both assertions and questions with the EF are felicitous in contexts where it is not taken for granted that the origo lacks direct evidence regarding the scope proposition (as shown in (35) and (38)). The hypothesis that the evidential requirement is an easily accommodatable presupposition might help with assertions but breaks down in the case of questions: it fails to predict why (39) is a possible reply to the question in (38). Assuming that the evidential requirement is a non-negotiable update is also problematic. On this view, A’s question in (38) would be putting forward an update (about B’s evidence) which B’s answer in (39) directly contradicts. Thus, the smoothness of the dialogue is unexpected under this proposal. In Sect. 3.4, we develop a modification of our original proposal that avoids these pitfalls.

3.4 The evidential requirement as an expressive presupposition

As we have seen, Murray (2017) treats the evidential requirement as an informative not-at-issue component along the lines of Potts’(2007a, 2007b) conventional implicatures. Some prime examples of conventional implicature triggers, according to Potts, are appositives (which Murray explicitly treats as parallel to the evidential requirement) and expressives (e.g., adjectives like damn). Schlenker (2007) argues that expressives can instead be analyzed as introducing a particular type of presupposition, which, given the logic of common belief in Stalnaker 2002, is predicted to be systematically informative. We contend that adopting Schlenker’s analysis for the evidential requirement of the EF successfully accounts for the issues discussed in Sect. 3.3.

3.4.1 Schlenker (2007)

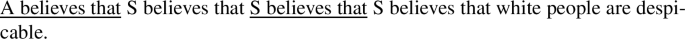

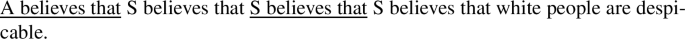

On Schlenker’s proposal, expressives trigger presuppositions that are always indexical (evaluated relative to a context) and attitudinal (they predicate something of the mental state of the agent of that context), and might be shiftable (some expressives can be interpreted relative to a context different from the context of the actual utterance). An example of shiftable expressive is the ethnic slur honky, which Schlenker analyzes as in (40). On this view, honky triggers a presupposition about the belief state of the agent of the context—which is always the speaker in root contexts, but can be a different individual in embedded contexts (e.g., in a reported speech act).

-

(40)

〚honky〛(c)(w) is defined iff the agent of c believes in the world of c that white people are despicable.

If defined, 〚honky〛(c)(w)=〚white〛(c)(w)

Schlenker shows that if we assume Stalnaker’s (2002) characterization of the common ground in terms of common belief, the presuppositions triggered by expressives are predicted to be always informative and self-fulfilling: an utterance of a sentence containing an expressive will automatically lead to the addressee believing its presupposition p, and to p becoming common ground. Let us see why.Footnote 23

Consider Schlenker’s example in (41). Assuming the lexical entry in (40), when (41) is uttered in a context c, it will trigger the presupposition p in (42) (where ‘S’ stands for ‘the speaker of c’).

-

(41)

I met a honky.

-

(42)

S believes that white people are despicable.

Now, assume that, at time t, (42) is not common ground. Assume further that, at time t+1, S utters (41). By doing so, S makes it clear that she believes that when the presupposition p of (41) is checked, it will be in the common ground. At time t+2, the participants in the conversation update their beliefs to take into account what happened at t+1. At that point, both participants in the conversation will have come to accept that S believes that the presupposition of (41) is common ground. Therefore, (43) obtains.

-

(43)

It is common belief that S believes that it is common belief that S believes that white people are despicable.

Given Stalnaker’s (2002) definition of common belief, if it is common belief (in a conversation between S (the speaker of c) and A (the addressee of c)) that q, then S believes that q and A believes that q. Thus, (43) entails (44) (where the first instance of it is common belief that has been replaced by A believes that and the second by S believes that).

-

(44)

Assuming that believers have introspective access to their own beliefs, (44) entails (45).

-

(45)

A believes that S believes that white people are despicable.

Finally, according to Stalnaker (2002), if it is common belief that S believes that it is common belief that p and A believes that p, then it follows that it is common belief that p. Thus, putting (43) together with (45) yields (46) (where p corresponds to ‘S believes that white people are despicable’).

-

(46)

It is common belief that S believes that white people are despicable.

We have then derived that the presupposition p triggered by honky in (42) is informative (the fact that S uttered (43) automatically lead to the hearer believing p, (45)) and self-fulfilling (p automatically becomes common ground, (46)).

3.4.2 The evidential requirement as an expressive presupposition

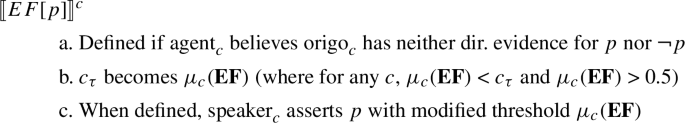

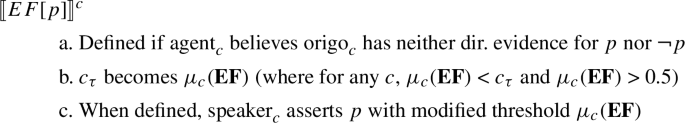

As anticipated, we propose that the evidential requirement of the EF is amenable to the same kind of analysis that Schlenker (2007) puts forward for expressives.Footnote 24 We thus re-formulate our evidential requirement (12)/(31) as in (47). Importantly, while the origo of c shifts to the hearer in questions, we take the agent of c to correspond to the agent of the speech act, which is the speaker in both questions and assertions.

-

(47)

\([\!\![EF [p] ]\!\!]^{c}\) is only defined if the agent of c believes in the world of c that the origo of c has neither direct evidence for p nor for ¬p.

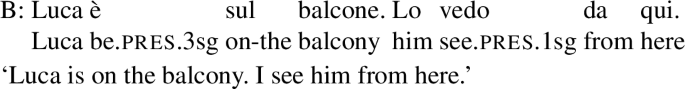

Let us see what the consequences of this move are. Consider a variation on the dialogue in (38)-(39), (48) below, uttered in the context in (49).

-

(48)

-

(49)

A and B are talking on the phone. B is at the beach. A assumes that B has not seen Luca today, but wants B to make a guess regarding whether Luca is at home. However, unbeknownst to A, Luca and B are spending the day together. B knows that A is not aware of this.

A’s question is felicitous in the context in (49). As discussed in Sect. 3.3, our previous formulation of the evidential requirement (31) (corresponding to (50) for this example) fails to predict this.

-

(50)

B (the hearer) has neither direct evidence for p (Luca is at home) nor for ¬p (Luca is not at home).

With our modified evidential requirement in (47), A’s question will now be taken to presuppose (51). As we we have seen, this presupposition is predicted to be self-fulfilling: A’s uttering her question will automatically result in (51) being added to the common ground. Crucially, (51) no longer clashes with B’s knowledge (B knowing that she has direct evidence regarding whether Luca is at home is compatible with A believing otherwise), so this addition will be unproblematic. B’s answer is also logically compatible with A’s presupposition (although it will lead to a revision of A’s beliefs). This correctly accounts for the felicity of A’s question in the context in (49), hence solving the problem raised in 3.3.

-

(51)

A (the agent of c) believes that B (the origo of c) has neither direct evidence for p (Luca is at home) nor for ¬p (Luca is not at home)

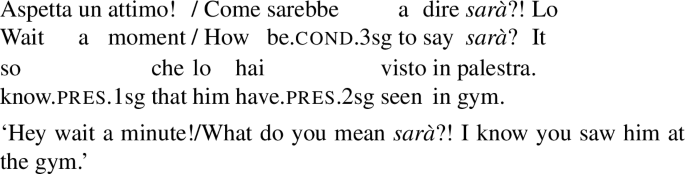

But now consider A’s question in (48) in the context in (52). In this case, the evidential requirement (51) does contradict B’s assumptions. This leaves two options available for B: she could accommodate the (false) presupposition by accepting it for the purposes of the conversation (see §3.3). Or, in a rather pedantic and unforgiving manner, she could contest the presupposition by replying something like What do you mean “sarà a casa”? You know we are spending the day together …. (The choice between the two responses will depend, as expected, on how important it is for B to establish the falsity of the presupposition.)

-

(52)

A calls B on her cellphone. A assumes that B has not seen Luca today, but wants B to make a guess regarding whether Luca is at home. B and Luca actually are spending the day together. B is convinced A knows this.

Let us now turn to the (systematic) oddity of questions like (16)/(33), repeated in (53). These questions are now predicted to presuppose that S believes that H does not have direct evidence for whether H has arrived home or not (53a) or whether, for any place x, H lives in x (53b). However, in most normal contexts, H can expect S to believe that H has direct evidence for whether he has arrived home/regarding where he lives. Given this, a discourse move that aims to add the proposition that S believes otherwise to the common ground is bound to cause oddity: accommodating this presupposition would amount to attributing unreasonable beliefs to the speaker. Of course, it is possible to construct far-fetched scenarios where the presupposition is satisfied. For instance, the weather is so bad that H will not be able to distinguish his building from the road, or H is an amnesiac that is trying to guess where he might live. Modifying the context so that it is plausible that the speaker believes that the hearer lacks direct evidence eliminates the oddity associated with these examples.

-

(53)

Let us now turn to assertions and discuss the other dialogue from Sect. 3.3, (35), repeated as (54) below. Here, the focus is on B’s assertion, which contains the EF.

-

(54)

Let us assume, as before, that—prior to B’s utterance—A (wrongly) assumed that B had direct evidence regarding Luca’s whereabouts. With our modified evidential requirement in (47), B’s reply in (54) will be associated with the presupposition in (55), which, as we have seen, will automatically become common belief after B’s utterance. Unlike in the case of questions, a further step is in principle possible here. Speakers can normally be expected to have true beliefs regarding their own evidence. If A assumes this about B, from (55) she will be able to infer (56) (which corresponds to our previous evidential requirement). This conflicts with A’s previous beliefs. However, as discussed in Sect. 3.3, we can in principle expect A to be willing to revise her beliefs when they are about B’s evidence, rather than her own. Given this, our revised presuppositional story makes the same (welcome) predictions for this example as an account à la Murray would.

-

(55)

B (the agent of c) believes that B (the origo of c) has neither direct evidence for p (Luca is at work) nor for ¬p (Luca is not at work)

-

(56)

B (the origo of c) has neither direct evidence for p (Luca is at work) nor for ¬p (Luca is not at work)

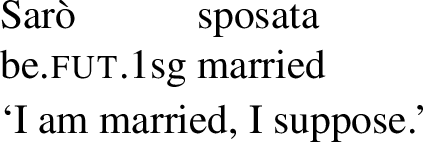

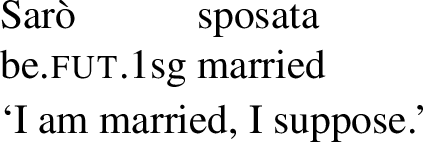

Just like in the case of questions, we expect assertions with the EF to be odd if the evidential requirement conflicts with common knowledge. The example in (57), for instance, is odd in most contexts (as speakers normally have direct evidence regarding their marital status), but would become felicitous if, e.g., the speaker is an amnesiac.

-

(57)

Let us summarize the results of this section. We have argued that the evidential requirement of the EF is not-at-issue, but that the not-at-issue analyses available in the evidentials literature make wrong predictions for the EF. We have seen that treating the evidential requirement as an expressive presupposition, following Schlenker (2007), captures the attested patterns. This discussion raises the question of whether evidentials across languages might be amenable to this kind of account, thereby opening up a new perspective on the study of evidentiality. In turn, this question highlights the need of collecting question-answer data like the ones we have argued pose a problem for a Murray-style account (§3.3), and, which, to our knowledge, haven’t been discussed in the literature on evidentials.

4 Analyzing the EF: The at-issue contribution

Most formal analyses of evidentials fall into one of the following two categories: (i) modal analyses, which treat evidentials as modal operators (e.g., Izvorski 1997, Matthewson et al. 2007, and—focusing specifically on the Italian EF—Mari 2010); (ii) illocutionary analyses on which evidentials are analysed as speech act modifiers (Faller 2002), or perform a separate common ground update (Murray 2017). However, even some of the latter approaches treat the at-issue component contributed by inferential evidentials as modal. For instance, Faller proposes that the inferential evidential she analyzes makes a (possibility) modal assertion (see AnderBois 2014 for discussion).Footnote 25 In Sect. 4.1, we depart from this view and contend that the EF is not amenable to an epistemic modal account. We instead propose that the at-issue contribution of an utterance of the form EF(p) is just p (a non-modalized proposition). Treating the at-issue component of the EF as non-modal has to face an obvious challenge: a speaker that utters a declarative sentence of the form EF(p) does not seem to be asserting p. In order to account for this fact, we adopt in Sect. 4.2 (a slightly modified version of) the proposal in Davis et al. (2007), on which the discourse function of evidentials in assertions is to shift the quality threshold of the context (the degree of confidence required for a speaker to make a successful assertion).

4.1 The at-issue contribution is not a modal proposition

The discussion in the preceding sections has already brought up some contrasts between the EF and epistemic modals. We saw in Sect. 2.2 that the origo of the EF in root declaratives must be the speaker, whereas epistemic modals allow for non-autocentric readings, as in the Mastermind example in (13). Another contrast emerges in evidence neutral scenarios like (11) (repeated below as (58)).

-

(58)

These cases seem to involve a pretense on the part of the speaker: although the speaker does not have any evidence that would favour the scope proposition, she puts this proposition forward in order to reassure the hearer.Footnote 26 The conversational import of the EF utterance in the scenario in (58) differs from the one associated with the epistemic modal claims in (59). The might statement in (59a) would presumably be true in (58) but would lack any comforting effect. The must statement in (59b) would be false, and thus perceived as inappropriate (unless Elena engages in wishful thinking and assumes that Carmela is basing her claim on evidence that she, Elena, is unaware of).

-

(59)

-

a.

He might be safe and sound.

-

b.

He must be safe and sound.

-

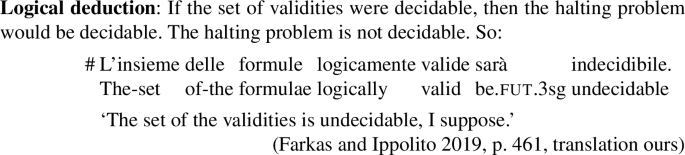

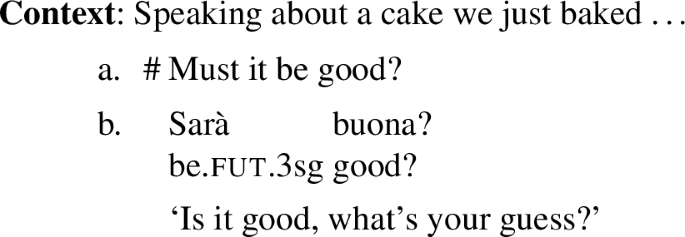

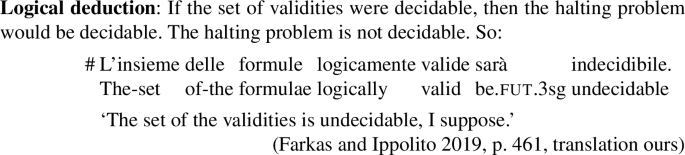

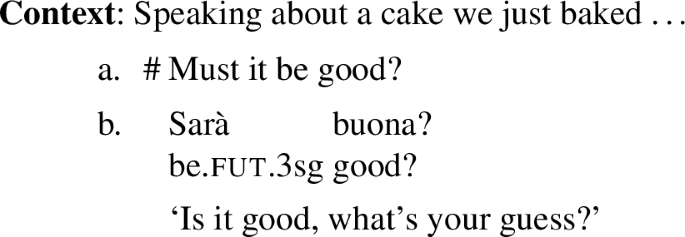

a.

Additional contrasts arise when we compare the EF specifically with epistemic necessity modals like must.Footnote 27 We saw that the EF can be used to convey guesses and conjectures and in such uses is compatible with epistemic adverbs that cannot occur with necessity epistemic modals (see, e.g., our example in (10)). Moreover, it has been shown (Mari 2010, Farkas and Ippolito 2019) that the EF is incompatible with pure logical deduction: in Farkas and Ippolito’s (2019) example in (60) below (adapted from Mandelkern 2019), the EF is ruled out but a must statement would be perfectly acceptable.Footnote 28,Footnote 29 Finally, as pointed out by Farkas and Ippolito (2022), questions provide us with yet another difference, witness the oddity of (61a) below, in contrast with the acceptability of (61b).

-

(60)

-

(61)

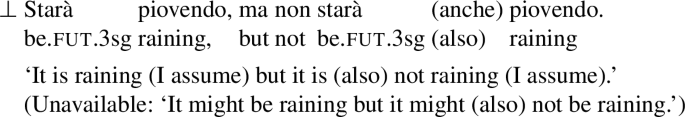

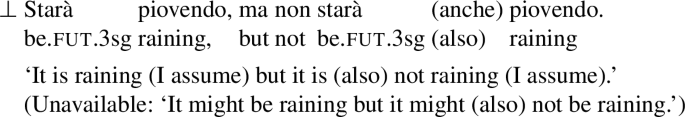

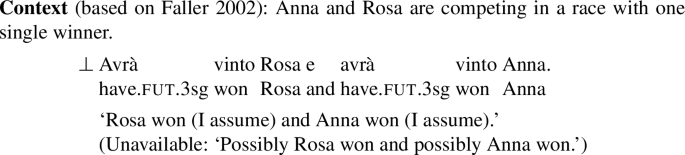

The EF also clearly differs from epistemic possibility modals. For instance, it cannot be used in contexts like (62) (adapted from Faller 2002), where the speaker is equally committed to the scope proposition and its negation, and where might would be appropriate. Accordingly, conjunctions of incompatible possibilities (which are available for possibility modals, as in (63)) are not possible for the EF: the examples in (64) and (65) sound contradictory.Footnote 30 Note that cases like (62) differ from the evidence-neutral examples discussed in Sect. 2.1. Intuitively, in the latter type of scenarios (e.g., the soldier example in (11)/(58)), the speaker presents herself as being more committed to the scope proposition than to its negation (hence, the comforting effect), despite lacking evidence for it.

-

(62)

-

(63)

It might be raining, but it might also not be raining.

-

(64)

-

(65)

Apart from discussing asymmetries with necessity and possibility epistemic modals, Farkas and Ippolito (2019, 2022) also show that the EF differs from probability and weak epistemic necessity modals. We believe that, taken together, all these contrasts make a convincing case that the EF is not an epistemic modal. At this point, two lines of attack present themselves. We could try to develop a non-modal account of the at-issue component of the evidential future or aim for a non-epistemic modal account. We pursue the first option, in Sect. 4.2. In Sect. 5, we discuss the non-epistemic modal account of the EF put forward by Farkas and Ippolito (2022) and ultimately conclude that our proposal compares favorably to that particular modal account.

4.2 Asserting p with weakened commitment

Assuming that the at-issue component of the EF is non-modal (that is, that the at-issue component of a sentence of the form EF(p) is simply p) leaves us with the question of why declarative sentences of the form EF(p) do not seem to assert p. As we have seen in Sect. 2.1, assertions with the EF tend to convey a weakened commitment toward the scope proposition. To address this question, we adopt a slightly modified version of the account in Davis et al. (2007), on which evidentials shift the quality threshold required for successful assertions.

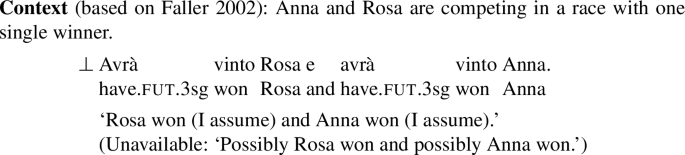

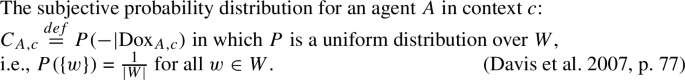

4.2.1 Davis et al. (2007)

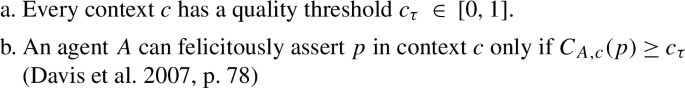

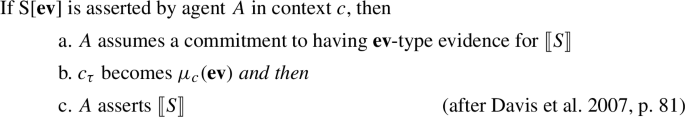

The core idea in Davis et al. (2007) can be summarized as follows. The authors endorse Lewis’s (1976) view of assertions (which involves a less demanding version of Grice’s Maxim of Quality): speakers can assert a proposition p as long as they take p to be very probably true. They formalize this by using the notion of quality threshold (from Potts 2007b), which corresponds to the minimum degree of credence required for a successful assertion in a given context. Evidentials (potentially) change the quality threshold (by lowering it or raising it). A speaker using an evidential will then be asserting the scope proposition relative to this new threshold. When an evidential ev lowers the threshold (as we argue the EF does), a speaker that utters a sentence of the form ev(p) asserts p even if she cannot fully commit to p.

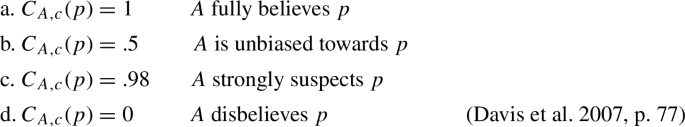

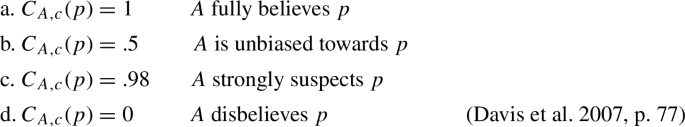

Let us flesh this out. Following Lewis, Davis et al. (2007) use subjective probabilities to model an agent’s belief state: they define a function \(C_{A, c}\) that maps any proposition p to A’s degree of belief in p in context c, as in (66). The examples in (67) illustrate how this function might model facts about A’s belief state.

-

(66)

-

(67)

The Lewisian notion of quality adopted by Davis et al. is spelled out in the following quote from Lewis (1976):

The truthful speaker wants not to assert falsehoods, wherefore he is willing to assert only what he takes to be very probably true. He deems it permissible to assert that A only if P(A) is sufficiently close to 1, where P is the probability function that represents his system of degrees of belief at the time. Assertability goes by subjective probability. (p. 133)

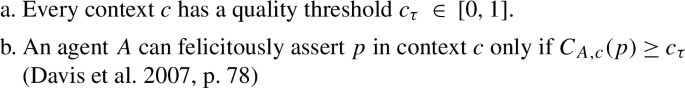

The concept of quality threshold is defined in (68a), and Lewisian quality is formalized as in (68b) (following Potts 2007b).

-

(68)

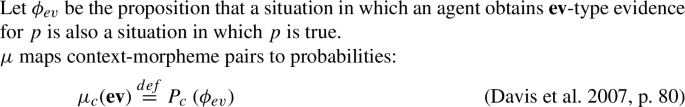

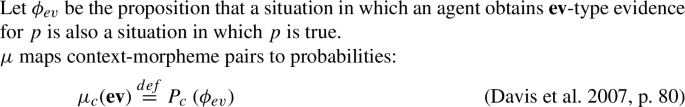

In order to model the contribution of evidentials, Davis et al. define a function that associates evidential morphemes with probabilities:

-

(69)

This function is argued to be context-dependent: while in most contexts direct evidence will be stronger than reportative evidence (so we might have, e.g., \(\mu_{c}\)(direct) = .98, and \(\mu_{c}\)(hearsay) = .75), there are contexts where direct perception is unreliable (e.g., if the speaker is known to hallucinate) and hearsay evidence perceived as highly reliable (because the source is perceived as highly trustworthy).

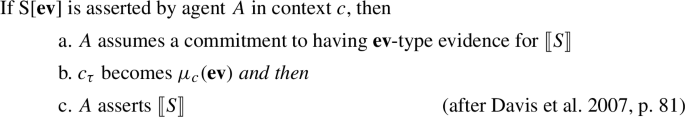

The theory of evidentials proposed by Davis et al. is summarized in (70). Evidentials specify the type of evidence that the speaker has for the scope proposition (70a), and shift the quality threshold (70b)Footnote 31 Hence, an assertion that was infelicitous before the shift can become felicitous afterwards (if the evidential lowers the threshold) or the other way around (if the evidential raises the threshold). In most cases, conjecturals and reportatives will lower the threshold, while direct evidentials will raise the threshold (giving rise to a strengthening effect, as Faller 2002 reports for Cuzco Quechua), but as noted above, this shift is context dependent. After the shift in threshold takes place, the speaker asserts the scope proposition (70c).

-

(70)

4.2.2 Applying Davis et al.’s proposal to the EF

We adopt a modified version of Davis et al.’s (2007) proposal for the EF. The modifications are as follows. First of all, we assume that the EF always lowers the quality threshold, as it does not seem possible for the EF to ever have a strengthening effect. We expect, however, the threshold for assertions with the EF to always remain above 0.5. This we take to follow from general (default) constraints on assertability: a speaker should not be able to assert a proposition p when she disbelieves p or is completely agnostic about whether p holds.Footnote 32 Second, we replace Davis et al.’s (2007) evidential requirement with our proposed evidential presupposition (§3.4). As a result, assertions with the EF are analyzed as in (71).

-

(71)

Given this, a speaker that utters a statement with the EF is asserting the scope proposition, but in a context with a lowered quality threshold. Weakened commitment towards p might then be derived via pragmatic reasoning (Davis et al. 2007). Threshold-shifting has to be motivated: a speaker that chooses to lower the threshold must have a reason to do so. The most likely reason is that she would like to add the scope proposition to the common ground but at the same time indicate that she cannot commit to it fully (due to lack of evidence or the evidence being not entirely compelling).Footnote 33,Footnote 34 On this view, the various degrees of confidence associated with EF assertions (§2.1) can be traced back to the different values that the quality threshold can take on (from just above 0.5—low confidence contexts—to close to 1—high confidence contexts). But cases where the speaker is completely agnostic with respect to the scope proposition p and where the use of an epistemic possibility modal would be appropriate (e.g., Faller’s umbrella scenario in (62)) are correctly predicted to rule out the use of the EF—in this type of scenario the speaker would not be able to assert p with a quality threshold higher than 0.5. The unacceptability of the EF in logical deduction contexts (e.g., (60)) is also expected if the EF lowers the threshold: lowering the threshold is not expected to be an appropriate conversational move when conveying the conclusion of a logical proof (unless the speaker is unsure about, e.g., the steps of the proof or the form of the argument).

What about evidence-neutral scenarios like the soldier scenario in (11)/(58)? We contend that, in these cases, the speaker either has a belief of credence in p that is higher than 0.5, or she presents herself as if she does: in (11)/(58), the speaker might actually believe to some extent the proposition that Elena’s husband is safe (after all, it is possible for agents to believe propositions for which they have no evidence). Alternatively, she might be pretending to do so, in order to comfort Elena (note that if the speaker were not expressing a commitment for p that is higher than chance, there would not be any comforting effect).Footnote 35

This proposal can also account for why the EF rules out conjunctions of incompatible propositions ((64)-(65)). We assume that the EF scopes over negation (this will allow us to maintain a standard view of negation as a truth-conditional operator directly combining with the scope proposition). Given this, a speaker that utters (64) would be conveying that her degree of credence in p is above 0.5 and that her degree of credence in ¬p is also above 0.5. Given this, an assertion of (64) imposes contradictory requirements on the speaker. This accounts for its oddity.

Let us take stock. We have put forward a proposal that accounts for the interpretation of the EF. The building blocks of the account are as follows. First, the evidential claim (a ban on direct evidence; von Fintel and Gillies 2010) is formalized as an attitudinal informative presupposition (in the sense of Schlenker 2007), anchored to a shiftable origo (Garrett 2001, Speas and Tenny 2003). Second, the EF lowers the quality threshold of the context (but never below 0.5). This requirement allows speakers to make assertions of the form EF(p) even when they cannot fully commit to p.

Before closing this section, a few words about questions are in order. Davis et al. (2007) suggest that their proposal may generalize to other types of speech acts but do not specify what the effect of (shifting) context thresholds may be outside of assertions. What could this component contribute in questions? We are not able to fully resolve this issue, and we limit ourselves to briefly sketch some possible options in the remainder of this section.

One possibility might be to assume that the lowering of the threshold has no effect in questions: the Lewisian notion of Quality formulated in (68b) above is only relevant for assertions. Another option would be to assume that the lowering of the threshold in questions waives some of the standard requirements on information seeking questions. In the model of discourse developed by Farkas and Bruce (2010), a canonical (information-seeking) question p? (i) raises an issue and indicates possible ways of updating the common ground (its possible answers), (ii) indicates that the speaker is ignorant regarding the resolution of the issue and that she believes the addressee may possess the relevant information, and (iii) requests that the addressee resolve the issue and update the common ground (with the propositional content of the true answer). Within this framework, lowering of the threshold may be taken as a signal about the projected state of the common ground, namely as an indication from the speaker to the addressee that she is allowed to provide an answer even if she is not fully committed to it. This, together with the (presuppositional) ban against direct evidence, would contribute to the conjectural flavor of EF-marked questions.

5 Comparison with Farkas and Ippolito (2022)

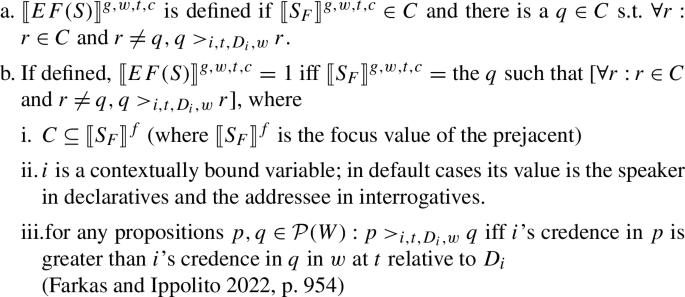

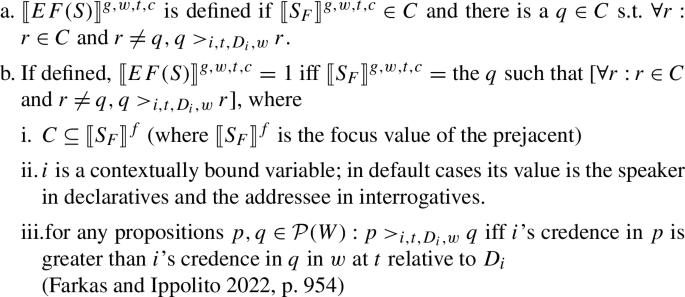

This section briefly compares our proposal to a recent alternative account, put forward by Farkas and Ippolito (2022), which treats the Italian EF (labelled ‘Presumptive Future’) as a special comparative subjective likelihood modal. On this account, a sentence of the form EF(S), where S denotes a proposition p, (i) presupposes that, among a set of salient propositions (a subset of the QUD), there is one that an agent i (the speaker in assertions/the hearer in questions) considers the most likely, relative to her doxastic state, and (ii) asserts that p is that proposition. This is spelled out in (72) (where C is a salient subset of \([\!\![S_{F} ]\!\!]^{f} \), the focus value of S, and \(D_{i}\) is the set of i’s doxastic alternatives).

-

(72)

Farkas and Ippolito further propose that an assertion of EF(p) gives rise to a mandatory implicature (Lauer 2014) that the speaker is not committed to p, due to a pragmatic competition between asserting p and asserting EF(p).

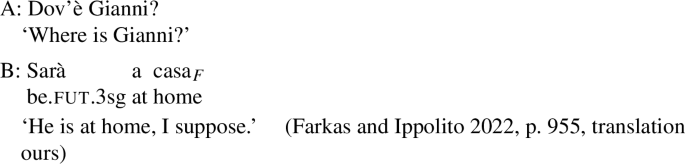

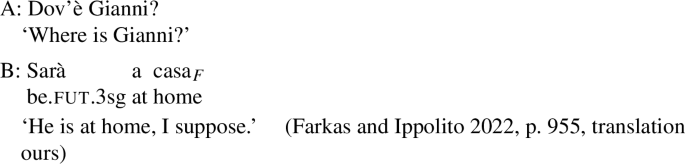

Let us briefly illustrate the proposal with Farkas and Ippolito’s example in (73).

-

(73)

The contextually relevant set C must be a subset of the QUD Where is Gianni?, e.g., Gianni is at home, Gianni is at the office, Gianni is at the movies. B’s utterance, with the EF, presupposes that one of these alternatives is more likely for B (given her doxastic state) than any of the others, and asserts that this alternative is that Gianni is at home. Additionally, B’s utterance implicates that B is not fully committed to the proposition that Gianni is at home. Farkas and Ippolito note that, on this view, the unavailability of the EF in scenarios where the speaker has direct evidence for p (e.g., (4)) would follow because in these cases the speaker can be assumed to believe that p is true.

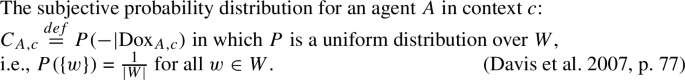

This proposal assumes that the EF is a rather unique creature, whose semantics differs from that of other previously described elements that signal weakened commitment to a proposition. Our take on the EF is substantially different. Since the EF systematically patterns with inferential evidentials (see §2), we have analyzed it using tools available in the literature on evidentials and other expressions (e.g., expressives) that convey not-at-issue content. We believe that, in principle, a proposal that situates the EF within the inferential evidential class should be preferred to one that doesn’t, unless there are empirical reasons to prefer the latter. In the remainder of this section, we discuss what we take to be the core components of Farkas and Ippolito’s account, namely (i) that the EF involves a comparison between alternatives (based on subjective likelihood) and that (ii) this comparison is conveyed via a presupposition. We conclude that the arguments that Farkas and Ippolito present for the comparative view are not conclusive, and that there are reasons to believe that a comparison between alternatives is not presupposed.

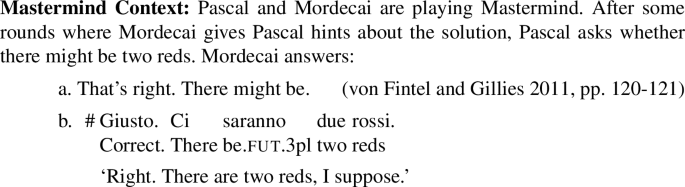

Farkas and Ippolito explicitly argue that a comparative notion of (subjective) likelihood is preferable to an absolute one, on which an utterance of the form EF(S) would convey that the relevant agent has a degree of credence that exceeds a particular threshold. On their view, a speaker that has a very low degree of credence for p can still utter EF(S) if she takes p to be the most likely alternative. In contrast, we are endorsing an absolute view: while the notion of threshold that we take from Davis et al. (2007) is also based on subjective probabilities (rather than objective likelihood), we assume that the quality threshold set by the EF in a given context must be lower than the contextually salient one, but above 0.5 (an absolute value). In what follows, we contend that Farkas and Ippolito’s (2022) arguments do not provide convincing evidence for the comparative view.

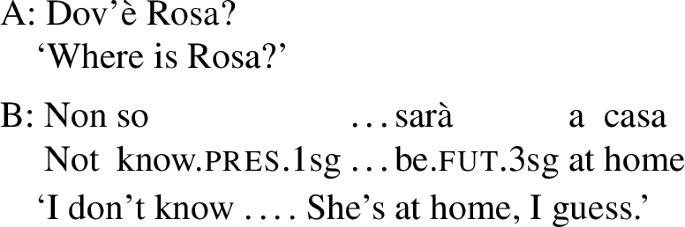

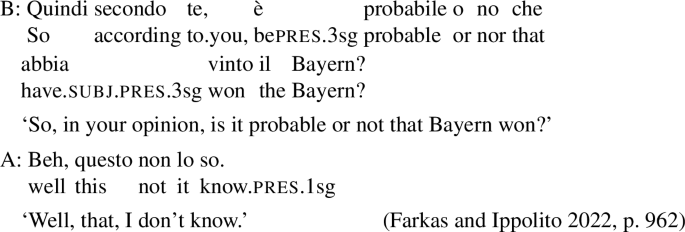

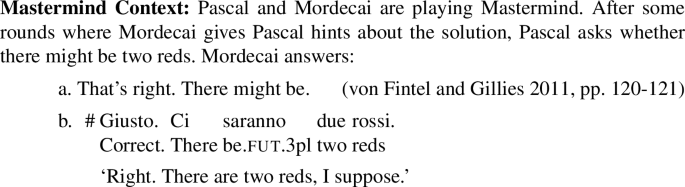

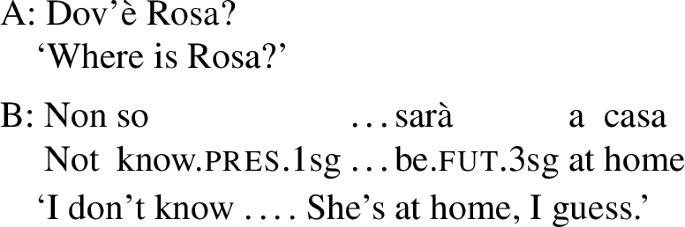

Their first argument involves ignorance scenarios. We have seen that assertions with the EF can be used to (partially) answer a question after the speaker has explicitly said that she is ignorant with respect to the issue raised by that question (see, e.g., our example (10)). Example (74) below illustrates this again. According to Farkas and Ippolito, this type of example supports the comparative likelihood hypothesis: in (74), speaker B is not assumed to believe that the scope proposition is subjectively more likely than some threshold of likelihood. The requirement is instead that there be no alternative the speaker gives higher credence to (Farkas and Ippolito 2022, p. 961).Footnote 36

-

(74)

But, as far as we can tell, examples like (74) are compatible with our claim that the quality threshold of the context must be above 0.5. B’s ‘I don’t know’ reply in (74) doesn’t in itself convey that she is completely agnostic with respect to the issue of Rosa’s whereabouts. It simply says that B doesn’t know the answer to the question. This is consistent with B thinking, e.g., that Rosa is likely to be at the beach. In fact, an ‘I don’t know’ reply in this context can also be felicitously followed with a probability modal, as in (75) below.

-

(75)

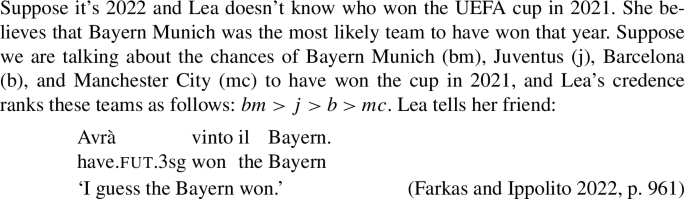

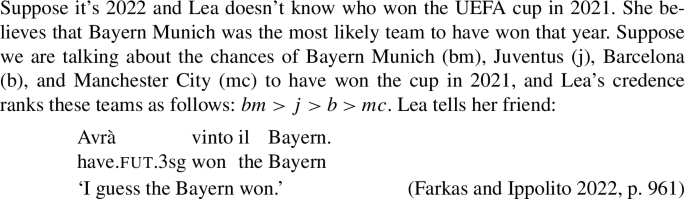

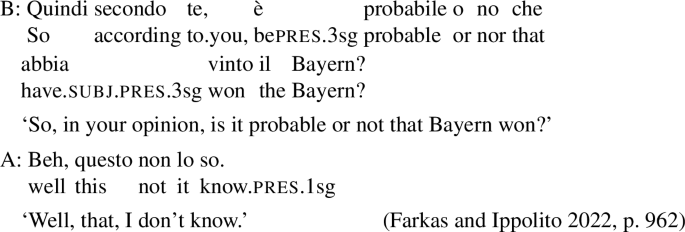

Farkas and Ippolito’s second argument involves scenarios where multiple possibilities are at play, as in (76). They claim that, in this scenario, one alternative is ranked higher than the others but still below a likelihood threshold of 0.5. Since the EF is acceptable here, they contend that this type of scenario provides evidence for the comparative approach.

-

(76)

In order to strengthen their point, Farkas and Ippolito offer the continuation in (77), intended to show that the speaker is not committed to the proposition that Bayern won.

-

(77)

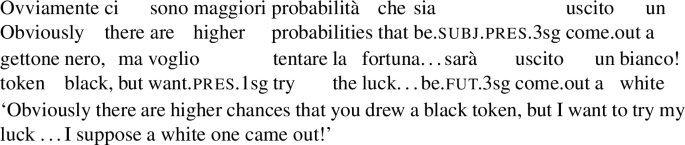

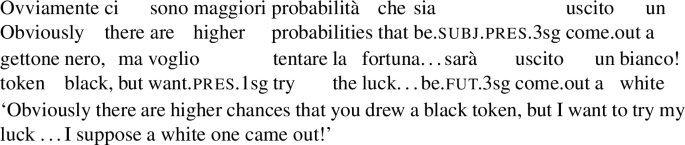

However, we argue that the ranking presented in (76) does not rule out the possibility that the speaker’s degree of credence for the highest ranked alternative is above 0.5. The fact that in (77) A doesn’t know whether p is probable is still compatible with A having a degree of credence in p that is above chance. The adjective probable has been argued to express a conclusion based on objective evidence (see Portner and Rubinstein 2012, which builds on Kratzer’s 1981 discussion of the German adjective wahrscheinlich). A speaker can declare herself ignorant with respect to whether p is (objectively) probable while still being (subjectively) biased for p. And they can even assert that the (objective) probability of a salient alternative is higher than that of p, while still expressing a (subjective) bias for p. As an illustration, consider the scenario in (78).

-

(78)

A and B are playing a game. A tells B: “in this bag there are 100 black tokens and 5 white tokens. If I draw a white token, you win. But if I draw a black token you lose.” Given this, B forms the belief that A is more likely to draw a black token than a white one. A draws a token from the bag and asks B to guess its color.

In this scenario, B can felicitously utter (79): her statement that it is more probable that a black token was drawn is perceived as consistent with her last (EF-marked) sentence, guessing that a white token was drawn (after all, one can believe in luck—objective probabilities notwithstanding).

-

(79)

The evidence so far does not favor the comparative view over the absolute view. We now turn to what we take to be a potential challenge for the comparative approach, as formulated by Farkas and Ippolito (2022), namely that the EF is felicitous in contexts where the comparative presupposition in (72) is not obviously satisfied.

Consider our evidence-neutral scenario, repeated in (80). Here, Carmela would be able to utter the assertion with the EF, addressing the implicit QUD ‘Is Elena’s husband okay?’, even if Elena does not assume, prior to Carmela’s assertion, that Carmela considers one answer to this question most likely than the other (in fact she may be very well convinced of the opposite).

-

(80)

Farkas and Ippolito could assume, as we have done for our evidential presupposition, that that their comparative presupposition is relativized to the speaker’s beliefs and is therefore self-fulfilling. If so, in the example above, Carmela’s assertion would trigger the self-fulfilling presupposition that Carmela believes (however irrationally) that there is one answer to the implicit QUD that is most likely than the others.

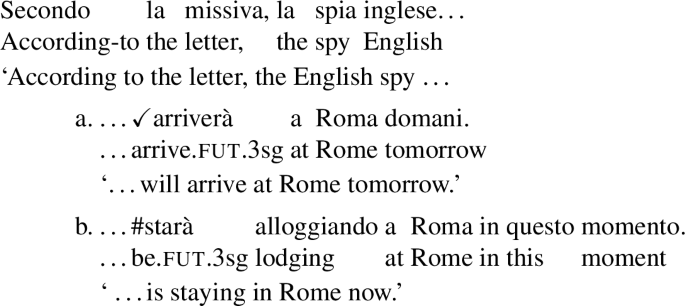

However, this strategy does not seem available for conjectural no-evidence questions. Consider (81) below. In this situation, A clearly does not assume that B considers one answer to the question more likely than the others. Still, the question with the EF is felicitous (and would not prompt a ‘Hey, wait a minute’ reply on B’s part). Perhaps Farkas and Ippolito could argue that these examples always involve accommodation. But it is not clear to us how this assumption would square with the acceptability of A’s follow-up question ‘Do you know anything about him?’ As Eckardt and Beltrama (2019) and Eckardt (2020) discuss for similar conjectural questions with German wohl, these questions can be used to invite the hearer to engage in a joint deliberation. They don’t require the speaker to believe that—prior to this deliberation—the hearer leaned towards a particular answer to the question.

-

(81)

To sum up: we have argued that Farkas and Ippolito’s (2022) account does not have the empirical upper hand. Given this, and given the parallelisms between the EF and evidentials across languages, we believe than an evidential account should be preferred.

6 Concluding remarks and issues for further research

We have provided extensive evidence that the Italian non-predictive future is an inferential evidential. Our analysis of this evidential has two core ingredients. First, we have claimed that the EF introduces a ban against direct evidence, modelled as a self-fulfilling attitudinal presupposition (Schlenker 2007), an analytical option that had not been explored for evidentials before. This accounts for the fact that questions with the EF are felicitous in contexts where the hearer has direct evidence for the answer (as long as the speaker is not expected to know this), something that was puzzling for previous accounts of evidentials. Second, we have argued that the EF is not amenable to an epistemic modal analysis. To account for the reasons that assertions with the EF involve a nevertheless weakened commitment, we have adopted Davis et al.’s (2007) proposal, on which evidentials shift the contextual quality threshold.

Many questions remain, of course. For instance, we have not discussed how this analysis might be extended to cases where the EF is embedded under attitudes. Another pressing question is to what extent the evidential and the temporal uses of the future can be traced down to a common core.Footnote 37 A unified account of these two uses seems desirable. Not only are inferential futures common cross-linguistically, but also (non-scheduled) temporal uses of future morphology have been argued to involve a subjective (conjectural-like) assessment, as in (82).

-

(82)

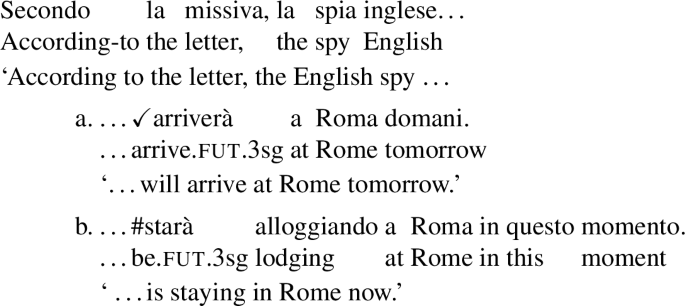

At the same time, a unified analysis would need to explain a number of contrasts between the EF and the temporal future. For instance, embedding under factives is difficult for the EF (see also Mihoc et al. 2019 on the Romanian inferential future) but unproblematic for the predictive future, witness (83). The predictive future also differs from the EF in that it can be anchored to a body of information, while the EF has to be anchored to a sentient individual (see (84)). Understanding how these contrasts might fit in a unified account of the future is a task that we will have to leave for further research.

-

(83)

-

(84)

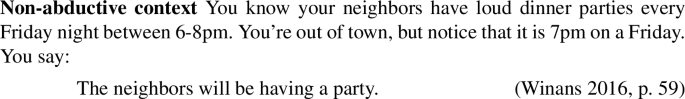

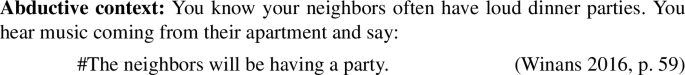

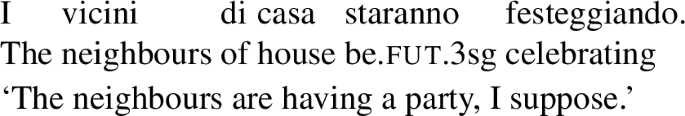

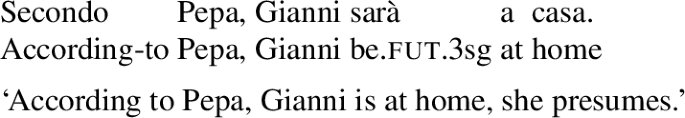

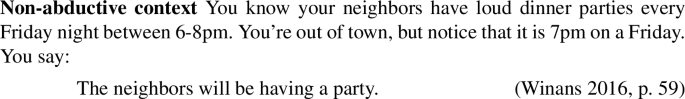

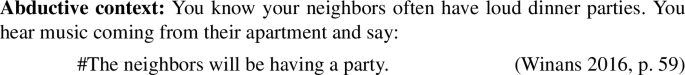

Yet another question concerns the extent to which inferential futures differ across languages. A systematic comparison with other Romance futures is beyond the scope of this article, but, as far as we can tell, the analysis given here could be extended to the Spanish inferential future (see, e.g., Rivero 2014). In contrast, a cursory comparison between the EF and inferential will reveals interesting contrasts. Winans (2016) shows that will is not acceptable in abductive contexts, as in (86), where the conclusion that the neighbours are having a party is assumed to explain the evidence (that there is loud music). The EF displays no such restriction: as noted (§2.1), the EF can be used to express the conclusion of an abductive inference. Accordingly, (87) is acceptable in both (85) and (86).Footnote 38

-

(85)

-

(86)

-

(87)

Further research is needed to determine what other parameters of cross-linguistic variation might distinguish inferential futures and how this variation can be explained.

Notes

Non-predictive uses of the future are also available in other Romance languages, with the exception of Catalan, as well as in non-Romance languages such as English, Dutch, Greek or Bulgarian (see, e.g., Squartini 2001, Giannakidou and Mari 2013, Fălăuş 2014, Fălăuş and Laca 2014, Mihoc 2014, Rivero 2014, Rivero and Simeneova 2015, Winans 2016, Mihoc et al. 2019). A cross-linguistic account of non-predictive futures is beyond the scope of this paper (but see §6 for some differences between the Italian future and English will). We also set aside the predictive use of the future and leave open the question of whether the two uses can be traced back to a common core (see Giannakidou and Mari 2013, 2018 for a unified account, and §6 for some brief remarks in connection to this).

See Krawczyk (2012) for discussion of these types of inferences in connection with inferential evidentials.

While in most of the paper we translate the EF with a parenthetical I suppose, in some examples (like (9)-(11)) we switch to translations that come closer to the intuitive contribution that the EF makes in those cases.

We do not attempt to model the type of inferences conveyed by the EF (see Krawczyk 2012 for a probability-based formalization of the reasoning process encoded by inferential evidentials).

An anonymous reviewer wonders if it might be possible to formulate the evidential component of the EF as a (very weak) indirect evidence requirement (e.g., along the lines of Mari 2010). While this kind of requirement would indeed be compatible with most of the facts discussed in this section, the acceptability of the EF in scenarios like (11) speaks against this option.

The Italian EF cannot be embedded in the antecedent of conditionals or under most attitude predicates. Some of these restrictions can be argued to follow from mood selection: the EF—part of the indicative paradigm—is disallowed under predicates that select for subjunctive in Italian. However, embedding under factives like sapere ‘know’, which are indicative-selectors, is also restricted. We leave a detailed discussion of the embedding patterns displayed by the EF for future research.

The EF can combine with according to-phrases that specify that the relevant evidence is that of a third person, as in (i) (contra Mari 2010). These cases can be assimilated to the examples where the EF is embedded under attitude verbs—according to-phrases create an intensional context (see discussion in Krawczyk 2012).

-

(i)

-

(i)

A closer look at the range of possible answers to EF-marked questions will force us to modify this version of the evidential requirement. See discussion in Sect. 3.4.