Abstract

Revolutions are invariably viewed as the violent replacement of an existing political order. However, many social innovations that result in fundamental institutional and cultural shifts do not occur via force nor have clear beginning and ending dates. Focusing on early-modern England, we provide the first-ever quantitative inquiry into such quiet revolutions. Using existing topic model estimates that leverage caselaw and print-culture corpora, we construct annual time series of attention to 100 legal and 110 cultural ideas between the mid-sixteenth and mid-eighteenth centuries. We estimate the timing of structural breaks in these series. Quiet revolutions begin when there are concurrent upturns in attention to several related topics. Early-modern England featured several quiet, but profound, revolutionary episodes. The financial revolution began by 1660. The Protectorate saw a revolution in land law. A revolution in caselaw relating to families was underway by the early eighteenth century. Elizabethan times saw an increased emphasis on basic skills and showed signs of a Puritan revolution affecting both theology and ideas on institutions. In the decade before the Civil War, a quiet revolution of dissent preceded the turmoil that led to a king’s beheading.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Earlier, Goldstone (2009) identifies a popular myth that revolutions are sudden expressions of widespread discontent, bringing about social change. But later, Goldstone points out that there are examples where this characterization does not fit, for example, the Meiji Restoration or the Chinese Revolution of 1911. However, all the revolutions he considers do happen very quickly, have political change at their core, and begin with intra-elite conflict. For Skocpol (1979), revolutions form an even smaller set: “Social revolutions have been rare but momentous occurrences in modern world history. From France in the 1790s to Vietnam in the mid-twentieth century, these revolutions have transformed state organizations, class structures, and dominant ideologies.“

The Oxford English Dictionary defines a quiet revolution as “a major social or political change achieved without violence or upheaval”, but then specifically connects the term to a period of social, economic, and educational reforms in Quebec. Web searches confirm that this is the most common usage of the term ‘quiet revolution’, even though it has been used sporadically throughout the past centuries. For example, in The (London) Times of May 18, 1859, page 10, the Turin correspondent, after opening with a comment on the weather, reports on the military and political situation in Rome, which is predicted to have a “quiet revolution” similar to the one that occurred in Florence.

Our reference to England in the paper’s title and throughout the paper’s text is less than precise but is the most accurate term for the geographical coverage of our paper. We study corpora on law and on culture. England was united with Wales in the thirteenth century, but it was only in 1830 that Wales was fully assimilated into the assize (or circuit) system from which important cases filtered into the top courts, and hence our database. Scotland retained its own legal system after its 1707 unification with England and Wales. Our culture corpus does include documents from Wales and Scotland. But Welsh-language and Scots Gaelic works would have been eliminated in our corpus pre-processing (see Sect. 2). Of course, English-language works produced by Welsh or Scottish authors are included. Nevertheless, the culture corpus is dominated by English works, and therefore a combination of parsimony and rough accuracy indicates our use of ‘English’ and ‘England’. Given the way in which these names are usually used in the literature, listing the other countries would imply an emphasis that we do not have in the paper.

“We are just beginning in economic history to take seriously ideas and their trace in language. But economists and economic historians…had a hard time of it” (McCloskey, 2016, p. 253).

These include the King’s (or Queen’s) Bench, the Court of the Common Pleas, the Exchequer, and the Chancery.

This was confirmed via our personal correspondence with Paul Schaffner, a TCP production manager.

Google books might be the one competitor. However, transcription quality in that corpus does not approach that of TCP and machine-readable versions of the Google-books texts are not generally available.

In personal correspondence with us, Paul Schaffner, a TCP production manager, noted that “personal preferences of any kind had virtually no influence on selection”. The reason is that “[the] selector’s job was to go through [the tracking database] picking unique works in English, picking the earliest copy (assuming it was complete), avoiding Latin, and so forth. There was simply no room to introduce personal preference into this mechanical and tedious task. This was not a ‘craft’ operation; it was a ‘production’ shop.“

Anticipating our findings discussed in Sects. 4 and 5, the sets of ideas captured by Keble-Style Reporting, Modern-Style Reporting and Coke-Style Procedural Rulings provide a case in point. The temporal evolution of relative attention to each of these three sets of ideas evidences a sharp rise at some point that is soon followed by a rapid decline (see Appendix C). But our empirical analysis, quite appropriately, does not estimate any breaks in the corresponding time series (see Table E1).

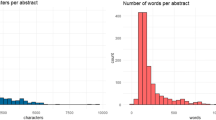

The corpora were further processed following the steps suggested for STM estimation (Roberts et al., 2019). All words were converted to lower case and stemmed. We removed standard English stop words, numbers, words with fewer than three characters, words included in only one document, and punctuation.

Before final estimation, the researcher must decide on the number of topics, that is, the number of sections of the digest. Using statistical criteria and a more subjective evaluation of the coherence and meaning of the produced topics, Grajzl and Murrell (2021a) chose 100 topics for the STM of the ER corpus and Grajzl and Murrell (2023c) chose 110 for the STM of the TCP corpus.

The existence of residual topics is a consequence of the fact that topic models “often shunt noisy data into uninterpretable topics in ways that strengthen the coherence of topics that remain” DiMaggio et al. (2013, p. 582). Reassuringly, all three series exhibit as a primary break a down break in the latter half of the seventeenth century or early eighteenth century (see Appendix E). This is consistent with the notion that the era of printing and the increasing emphasis on the vernacular in both religion and law led to greater standardization of the language and less use of Latin.

Relative to simultaneous estimation of multiple unknown breaks, the sequential approach has been shown to be comparatively more robust to misspecification (Bai, 1997).

Bai and Perron (1998, p. 63), for example, characterize the first break point as “dominating in terms of the relative magnitudes of shifts and the regime spells”.

We use the standard value of 0.15 for the ‘trimming’ parameter, implying that in testing for unknown breaks we exclude the first and the last 15% of the observations.

When a rise in attention is large enough to cause a break, it is due to contention about a particular subject, where there are proponents of some particular point, A, or its complement, ~A. The down break occurs when a large proportion of society has accepted either A or ~ A. We usually name the topic according to the ‘winner’.

The rise in attention to this topic in the late sixteenth century can be attributed to the fact that around this time the main common-law courts, the Common Pleas and the King’s (Queen’s) Bench battled about the appropriate legal action for such disputes (Baker, 2019, pp. 454–455).

This conclusion is entirely consistent with the evidence inGrajzl and Murrell (2021b) who use different methods to conclude that “[e]mphasis on precedent-based reasoning increases by 1650, but diffusion was gradual, with pertinent ideas solidifying only after 1700.“ That is, using the method for ascertaining unknown breaks, we have identified the start of the process of faster diffusion.

There was no widespread attempt to reverse the caselaw rulings on property that had occurred during the Commonwealth.

Even though the first Restoration Parliament annulled all legislation passed from 1646 to 1659 (with the exception of the provisions covered by the 1660 Declaration of Breda), the most important property legislation, which targeted the core of the existing land tenure system, was immediately reinstated by the same parliament (see, e.g., Jenks, 1938, p. 242). Therefore, related caselaw developed before 1660 would have still been relevant.

SeeGrajzl and Murrell (2021b): Sect. 3) and references therein.

The four up breaks in the final years of the century are on areas of law that are substantively unrelated to each other (Municipal Charters, Evidence Gathering & Admissibility, Geographic Settlement of the Poor, Equity Appeals).

An empirical argument would simply note that, for ER, ups and downs are nearly equal, with the latter slightly bigger. The theoretical argument is as follows. An up break occurs because a particular subject matter grabs attention. A down break occurs because a particular subject matter is losing the limelight. Suppose the data begin in a time when cultural patterns are stable, with no breaks occurring. Then this settled cultural progression is jogged out of its equilibrium by a sudden focus on a specific set of topics, which grab attention with all others experiencing slight, but not statistically significant declines (recall that our time series reflect relative attention). And then this new era remains stable until the data end. It is feasible in such a case, that there are many up brakes and no down breaks.

Mokyr (2016) focuses on later years than we do when emphasizing the cultural importance of the 3 C’s. However, this probably reflects his interest in the spread of ideas and their use, while this paper concentrates on finding the time period when these ideas were innovative. Harkness (2007) does see the 3 C’s as present in sixteenth century London.

The term Puritan loosely refers to those who wanted to purify English Protestantism from all vestiges of Catholicism, particularly emphasizing the basing of all religious practices on the Bible. Within Puritanism, there were many shades of theology and practice, the two most readily identifiable groups being Presbyterians and Congregationalists. On the origins of Puritan thought and action in Elizabethan England see, for example, Walzer (1982) and Marshall (2017).

Mokyr (2016, p. 246) emphasizes “a trail blazed by Bacon and the Puritans who admired him”, whereas our data suggests that Bacon built a road following a trail that clearly existed already.

Bacon’s maternal grandfather was a Marian exile (Garrett, 1938). His mother fostered Puritan causes as much as was possible given that she was a woman living in a polity with a Queen who was an ardent anti-Puritan. After Bacon’s father died, his mother was willing to use her command over family resources to influence her profligate sons (Magnusson, 2001).

There are many elements of Bacon that were enthusiastically endorsed by later generations. Here we focus only on his emphasis on the experimental and inductive; we have no comment to make on two other sets of ideas often associated with Bacon by later followers, the utilitarian promise of science and the centralized organization of the scientific quest. On these, see Grajzl and Murrell (2019).

The remaining three include one on religion without any political overtones and two on the 3 C’s.

Consider this introduction to an introductory English history course: “Culturally, the Restoration is best known as a backlash against the Puritan rule it followed. Specifically, society and culture around the king was characterized by loosened morals, more opulent displays of wealth and learning, and the celebration of the bawdy and the bodily. While much of that was limited to the court culture around London, Charles’s court became the center of English culture, as he and his followers became the most important patrons of the arts.“ (https://resources.saylor.org/wwwresources/archived/site/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/ENGL203-OC-1.1.1-Restoration18thcintro.pdf, accessed February 18, 2023).

See also Grajzl and Murrell (2019).

References

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2012). Why nations fail: The origins of power, prosperity, and poverty. New York, NY: Random House.

Bai, J. (1997). Estimating multiple breaks one at a time. Econometric Theory, 13(3), 315–352.

Bai, J., & Perron, P. (1998). Estimating and testing linear models with multiple structural changes. Econometrica, 66(1), 47–78.

Bai, J., & Perron, P. (2003a). Computation and analysis of multiple structural change models. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 18(1), 1–22.

Bai, J., & Perron, P. (2003b). Critical values for multiple structural change tests. Econometrics Journal, 6(1), 72–78.

Baker, J. (2019). An introduction to English legal history (Fifth edition.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Blei, D. M. (2012). Probabilistic topic models. Communications of the ACM, 55(4), 77–84.

Brown, R. C. (1931). The law of England during the period of the Commonwealth. Indiana Law Journal, 6(6), 359–382.

DiMaggio, P., Nag, M., & Blei, D. (2013). Exploiting affinities between topic modeling and the sociological perspective on culture: Application to newspaper coverage of U.S. government arts funding. Poetics, 41(6), 570–606.

Erickson, A. L. (1993). Women and property in early modern England. London, UK: Routledge.

Garrett, C. H. (1938). The Marian exiles: A study in the origins of Elizabethan Puritanism. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Goldstone, J. A. (2009). Rethinking revolutions: Integrating origins, processes, and outcomes. Comparative Studies of South Asia Africa and the Middle East, 29(1), 18–32.

Goldstone, J. A. (2014). Revolutions: A very short introduction. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Grajzl, P., & Murrell, P. (2019). Toward understanding 17th century English culture: A structural topic model of Francis Bacon’s ideas. Journal of Comparative Economics, 47(1), 111–135.

Grajzl, P., & Murrell, P. (2021a). A machine-learning history of English caselaw and legal ideas prior to the Industrial Revolution I: Generating and interpreting the estimates. Journal of Institutional Economics, 17(1), 1–19.

Grajzl, P., & Murrell, P. (2021b). A machine-learning history of English caselaw and legal ideas prior to the Industrial Revolution II: Applications. Journal of Institutional Economics, 17(2), 201–216.

Grajzl, P., & Murrell, P. (2022a). Lasting legal legacies: Early English legal ideas and later caselaw development during the Industrial Revolution. Review of Law & Economics, 18(1), 85–141.

Grajzl, P., & Murrell, P. (2022b). Using topic-modeling in legal history, with an application to pre-industrial English caselaw on finance. Law and History Review, 40(2), 189–228.

Grajzl, P., & Murrell, P. (2022d). Did caselaw foster England’s economic development during the Industrial Revolution? Data and evidence. SSRN Working Paper 4269309.

Grajzl, P., & Murrell, P. (2023a). A macrohistory of legal evolution and coevolution: Property, procedure, and contract in early-modern English caselaw. International Review of Law and Economics, 73, 106113.

Grajzl, P., & Murrell, P. (2023b). Of families and inheritance: Law and development in England before the Industrial Revolution. Cliometrica, forthcoming, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11698-022-00255-8.

Grajzl, P., & Murrell, P. (2023c). A macroscope of English print culture, 1530–1700, applied to the coevolution of ideas on religion, science, and institutions. SSRN Working Paper 4336537.

Grimmer, J., Roberts, M. E., & Stewart, B. M. (2022). Text as data. A new framework for machine learning and the social sciences. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Habakkuk, H. J. (1965). Landowners and the Civil War. Economic History Review, 18(1), 130–151.

Harkness, D. E. (2007). The jewel house: Elizabethan London and the scientific revolution. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Hodgson, G. M. (2017). 1688 and all that: Property rights, the glorious revolution and the rise of British capitalism. Journal of Institutional Economics, 13(1), 79–107.

Hodgson, G. M. (2023). The wealth of a nation: Institutional foundations of English capitalism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Jenks, E. (1938). A short history of English law (Fifth Edition.). London, UK: Methuen & Co. Ltd.

Langelüddecke, H. (2007). ‘I finde all men & my officers all soe unwilling’: The collection of ship money, 1635–1640. Journal of British Studies, 46(3), 509–542.

Macfarlane, A. (1978). The origins of English individualism: The family, property, and social transition. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Magnusson, L. (2001). Widowhood and linguistic capital: The rhetoric and reception of Anne Bacon’s epistolary advice. English Literary Renaissance, 31(1), 3–33.

Marshall, P. (2017). Heretics and believers: A history of the English reformation. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

McCloskey, D. N. (2016). Bourgeois equality: How ideas, not capital or institutions, enriched the world. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

McInnes, A. (1982). When was the English revolution? History, 67(221), 377–392.

Mokyr, J. (2016). A culture of growth: The origins of the modern economy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Murrell, P. (2017). Design and evolution in institutional development: The insignificance of the English Bill of Rights. Journal of Comparative Economics, 45(1), 36–55.

North, D. C., & Weingast, B. (1989). Constitutions and commitment: The evolution of institutions governing public choice in seventeenth-century England. Journal of Economic History, 49(4), 803–832.

Ogilvie, S., & Carus, A. W. (2014). Institutions and economic growth in historical perspective. In P. Aghion, & S. N. Durlauf (Eds.), Handbook of economic growth (2 vol., pp. 403–513). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Perron, P. (2006). Dealing with structural breaks. In T. C. Mills, & K. Patterson (Eds.), Palgrave handbook of econometrics (1 vol., pp. 278–352). New York, NY: Econometric Theory.

Plucknett, T. F. T. (1948). A concise history of the common law (Fourth edition.). London, UK: Butterworth & Co.

Reich, J., Tingley, D., Leder-Luis, J., Roberts, M. E., & Stewart, B. M. (2015). Computer‐assisted reading and discovery for student‐generated text in massive open online courses. Journal of Learning Analytics, 2(1), 156–184.

Reid, C. J. Jr. (1995). The seventeenth-century revolution in the English land law. Cleveland State Law Review, 43(2), 221–302.

Renton, A. W. (1900–1932). The English Reports. Great Britain. Parliament. House of Lords. Edinburgh, UK: W. Green & Sons.

Roberts, M. E., Stewart, B. M., Tingley, D., Lucas, C., Leder-Luis, J., Gadarian, S. K., Albertson, B., & Rand, D. G. (2014). Structural topic models for open-ended survey responses. American Journal of Political Science, 58(4), 1064–1082.

Roberts, M. E., Stewart, B. M., & Airoldi, E. M. (2016). A model of text for experimentation in the social sciences. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 111(515), 988–1003.

Roberts, M. E., Stewart, B. M., & Tingley, D. (2019). Stm: R package for structural topic models. Journal of Statistical Software, 91(2), 1–40.

Skocpol, T. (1979). States and social revolutions: A comparative analysis of France, Russia and China. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Thagard, P. (1992). Conceptual revolutions. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

The Text Creation Partnership (TCP) (2022). URL: https://textcreationpartnership.org.

Walzer, M. (1982). The revolution of the saints: A study in the origins of radical politics. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mehrdad Vahabi for support and encouragement, Paul Schaffner for many insights about the TCP project, Joel Mokyr and Mikki Brock for help with sources, and two anonymous reviewers and seminar participants at West Virginia University for valuable comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Grajzl, P., Murrell, P. Quiet revolutions in early-modern England. Public Choice (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-023-01093-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-023-01093-6