Abstract

Pre-electoral coalitions (PECs) may increase parties’ chances of winning an election, but they may also distort electoral results and policies away from citizens’ preferences. To shed light on how PECs shape post-electoral power distribution, we study the causes and consequences of PECs in Finland where elections use an open-list proportional representation system, and parties may form joint lists. We present descriptive evidence showing that PECs are more common between parties of equal size and similar ideology, and when elections are more disproportional or involve more parties. Using difference-in-differences and density discontinuity designs, we illustrate that voters punish coalescing parties and target personal votes strategically within the coalitions, and that PECs are formed with the particular purpose of influencing the distribution of power. PECs increase small parties’ chances of acquiring leadership positions, lead to more dispersed seat distributions, and sometimes prevent absolute majorities. They can thus enable a broader representation of citizens’ policy preferences.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Political parties are often viewed as coalitions of like-minded individuals that seek to implement policies that might not otherwise garner enough support. As such, parties assume the responsibility of safeguarding the platforms they articulate during election campaigns and establishing mechanisms to regulate the decisions of elected officials (Cox & McCubbins, 1993, 2005; Levy, 2004). However, instead of running on their own, parties across the world are increasingly joining forces before elections (Powell, 2000; Golder, 2005, 2006a). Pre-electoral coalitions (PECs) between political parties can be an effective strategy for parties to increase their chances of winning elections, but they also have the potential to dilute party ideology and policy platforms. Thus, they may pose a challenge to the conventional role of political parties as intermediaries between citizens and the state.

The main goal of this paper is to examine the implications that PECs have for democratic politics. What constraints do parties face when forming PECs? How do PECs influence political representation and the distribution of power? In the essence, are PECs formed purely for vote-seeking reasons, or are there other strategic considerations behind them?

To shed light on these questions, we construct a new data set of parties and their coalitional ties in local elections in Finland. Finland has an open-list proportional representation electoral system in which parties can form PECs by running joint lists. The parties have incentives to form PECs, because the (open-list) proportional representation system with D’Hondt method favors larger parties in the seat allocation (Benoit, 2000). PECs can be formed without any commitment to a joint policy manifesto after the election. Moreover, the coalition partners’ party labels remain visible in the ballot. These small barriers to entry to forming coalitions make such agreements frequent and yield rich large-N data for our study.

We begin our empirical analysis by studying how different contextual factors correlate with the presence of PECs at the municipal election level. This analysis confirms that hypotheses formulated by Sona Golder in her seminal work (Golder, 2005, 2006a, 2006b) also apply to the Finnish case. More specifically, PECs are more likely when more parties are present and when the electoral system at the local level is very disproportional. These correlations suggest that PECs are formed both to signal the likely voting coalitions after the election and to exploit the electoral returns to scale.

To better understand the motivations behind PEC formation, we study the various effects of PECs. We view this as our main contribution. An advantage of considering the Finnish open list municipal elections is that we observe the vote count for each candidate, and thus, the vote count for each party separately, even if the party was part of a PEC. We leverage party-level data on both coalition formation and electoral outcomes to examine the effect of coalition formation on electoral support and distribution of political power.

Our difference-in-differences analysis suggest that parties that join PECs face puzzling consequences. Coalescing negatively affects vote and seat shares, on average. This contradicts the motivation behind larger candidate lists to save electoral costs (Osborne & Tourky, 2008; Montero, 2016). Voter punishment of coalitions is targeted particularly to coalitions with large ideological heterogeneity. We also find that PECs encourage intra-list strategic voting as voters from smaller coalition partners pool their votes into fewer candidates, hence increasing their electoral chances in the within-list competition against candidates from larger coalition partners. Strategic voting seems to benefit smaller parties within the coalition, which might explain why asymmetric coalitions occur less frequently. We also find that some parties are willing to form PECs and give away important leadership positions to their smaller partners.

Given these negative repercussions of electoral alliances, what could be driving parties’ decisions to form such coalitions? Using data on municipalities and a difference-in-differences estimation strategy, we document that PECs increase small parties’ chances of acquiring leadership positions, lead to more dispersed seat distributions, and sometimes prevent absolute majorities. Our work thus highlights a novel bargaining power hypothesis by which coalitions are strategically formed to influence the overall distribution of seats; more specifically, to influence the probability that any party obtains an absolute majority of seats and gains full political control of the municipality

In order to further explore the role of PECs on the likely government composition, we use a density discontinuity design. The results suggest that PECs are an efficient tool for preventing absolute majorities when the largest party is close to obtaining more than half of the seats.Footnote 1 This same rationale to coalesce is at the core of the study by Frey et al. (2021). They document that in Mexican mayoral elections, parties are willing to compromise ideology and form an electoral alliance to remove an entrenched incumbent party from office.

The case of the Alavieska municipality in Northern Finland in the 2012 election illustrates our point. Four ideologically diverse parties (the National Coalition Party, the Left Alliance, the Christian Democrats, and the Finns Party), as depicted in Fig. 1 below, formed an electoral alliance to prevent the Center Party from obtaining an absolute majority of the seats. The municipality had been dominated by the Center Party for years, and the spokesman for the Left Alliance, Timo Takkunen, stated that they “wanted to make sure that the policies reflect the opinions of all inhabitants and not only the those of the Center Party supporters.”Footnote 2 In the end, the coalition did not obtain its objective, possibly due to the lack of ideological cohesion.

Ideological positions of Finnish main political parties. Notes: The ideological positions are drawn according to survey data on electoral candidates’ economic policy preferences from the Finnish Broadcasting Company YLE (see Sect. 4 and Appendix A for further information). The parties that formed a PEC in Alavieska to undermine the chances of the Center Party obtaining a majority of the seats are indicated in bold

Another interesting example occurred in the municipality of Karvia. In the 2012 election, two ideologically close parties, the Social Democratic Party and the Left Alliance, formed a PEC that ensured the Center Party did not get a majority of the seats. The last elected candidate was from the Social Democratic Party, and the first non-elected candidate was from the Center Party. Had the PEC not formed, the Center Party would have obtained one more seat and reached an absolute majority of the local council seats.

In the next section, we introduce the institutional context of our study. We then lay out our central theoretical considerations and empirically testable hypotheses. After describing our data, we present our empirical findings on the correlates of PEC formation and the effects of electoral alliances at the party and municipality levels. Prior to our final concluding section, we discuss the robustness of our findings in considering dyadic data with all possible two-party combinations.

2 Institutional context

Decision-making in Finnish municipalities is led by local councils.Footnote 3 Decisions are taken by a simple majority of the council members—thus, parties with absolute majority have full control of municipal activities.

Councils are elected using an open-list at-large proportional representation election system.Footnote 4 Municipal elections take place every 4 years. Votes are directed to a single individual candidate and not to a party. Seats in the municipal council are distributed using the D’Hondt method. That is to say, the number of seats for a political party depends on the total number of votes received by its candidates, and the seat allocation within the electoral list depends on the number of votes received by each candidate. The number of seats in each municipal council is a deterministic step function of the population in the municipality, and varies between 13 and 85 with a median of 27.

Municipal elections held between 1996 and 2008 were dominated by three large parties from the political left, center, and right: the Social Democratic Party, the Center Party, and the National Coalition Party, respectively. In 2012, the populist party True Finns became the fourth largest party. Other parties that hold seats in both municipal councils and the national parliament include the Left Alliance, the Green Party, the Swedish People’s Party and the Christian Democrats. Many municipalities have local, often independent or one-agenda political groups, that are not registered parties but hold seats in local councils.

About one third of the municipalities are governed by single-party absolute majorities despite the proportional representation system (Meriläinen, 2019). Most often, it is the Center Party that controls an absolute majority of the council seats.

Parties are allowed to form PECs in local elections. In the Finnish context, forming a PEC simply means that the parties set a joint list of candidates. A PEC between two or more parties is treated as a single party list when assigning votes to seats. Coalescing parties appear as separate parties on the candidate list provided to the voters at the polling booths, but the list clearly indicates the pre-electoral alliances that are in place. For an illustrative example, see Fig. 2 that shows the candidate list in the Evijärvi local government election of 2017 where the Social Democrats and the Left Alliance as well as the Center Party and the Christian Democrats formed PECs.Footnote 5

After the election, the newly elected council appoints a municipal executive board where parties are represented according to their seat shares in the council. The council elects by majority rule the chairman of the municipal board, which is considered to be the most important local political office, and the chairman of the council, which is considered to be the second-most important position.Footnote 6 The council can also set up committees to deal with different functions of the local government. No official ruling coalition government is formed after the election, though sometimes parties may form informal coalitions. Councils vote on an issue by issue case, and post-electoral voting coalitions may change from one vote to another.

Candidate list in Evijärvi local government election of 2017. Notes: Parties from left to right are the Finns Party, the Social Democratic Party, the Left Alliance, the National Coalition Party, the Christian Democrats, and the Center Party. Lines connecting the parties indicate PECs that have been formed by the Social Democrats and the Left Alliance, and the Christian Democrats and the Center Party. Candidate numbers, names, and occupations are shown in boxes

3 Theoretical considerations

We study the strategic formation of PECs and how PECs affect voting behavior and other electoral outcomes. We group our arguments into causes and consequences of PECs.

3.1 When are pre-electoral coalitions formed?

Taking cues from the work by Golder (2005, 2006a, 2006b) on pre-electoral coalitions, we are first interested in how the local election level circumstances might shape parties’ incentives to form joint lists. This initial set of hypotheses, and the corresponding empirical analyses, can be seen as a sanity check for our study vis-á-vis the previous work on PEC formation.

In proportional electoral systems, voters often face high uncertainty about the identity of future governments, which might discourage them from voting. The more political parties there are, the more difficulties voters have in anticipating the likely coalitions after the election. Under these circumstances, politicians might want to improve the information voters have by signaling the likely partners after the election: PECs should be more likely when there is a large number of parties.Footnote 7

The mechanical benefit of forming a coalition relies on the fact that bigger parties benefit from the apportioning of votes to seats. The key driver of this effect is the degree of disproportionality in each district which depends on the particular distribution of vote shares in the municipality, the electoral rule, and the council size. Parties in municipalities with particularly disproportional representation should have the largest incentive to form a PEC (see Blais and Indridason (2007) and Parigi and Bearman (2008)).

Whether two parties decide to join forces also depends on the characteristics of each party and not just the electoral context. A factor that might encourage two parties to form an alliance is a shared ideology (Golder, 2006a; Debus, 2009; Allern & Aylott, 2009; Ibenskas, 2015). For example, Golder (2006a) argues that coalitions amongst ideologically close parties should be more acceptable to voters of these parties and should result in smaller expected policy costs for the parties.Footnote 8

The similarity between coalition partners might not only concern their ideology but also their expected vote share. Asymmetry within coalitions should negatively affect the likelihood of forming an alliance as there might be more difficulties in agreeing a joint platform when bargaining between unequal partners. Bigger parties might feel smaller parties’ ideology is over-represented in the coalition and smaller parties might feel their wishes are silenced by the bigger partner in the coalition.

In all, we should expect more PECs in a municipality when there are more parties, the degree of disproportionality is largest, and when parties are more similar to each other (in terms of ideology and size).

3.2 Consequences of pre-electoral coalitions

Our second group of arguments is related to the consequences of PECs. We focus on three key outcomes: votes, seats, and control of the municipality (via leadership positions and by obtaining an absolute majority of councilors).

If PECs reduce campaigning and candidate selection costs (Osborne & Tourky, 2008; Montero, 2016), we should observe such coalitions having more resources to attract votes. However, the opposite might hold true as voters might dislike their party identity diluted within a coalition. Seeing the specific candidates citizens are voting for (recall that Finland has an open-list PR electoral system) allows us to identify which parties gain or lose from forming a coalition. This characteristic also makes it possible to investigate whether voters are sophisticated (Downs, 1957; Duverger, 1954): voters of small coalition partners could pool their votes to fewer candidates who can then compete with the candidates from larger coalition partners on the list.

Votes are simply the means to seats and leadership positions. What is the effect of PECs on seats? Whilst joining a PEC could harm parties’ vote shares, it is possible that the mathematics of apportionment improves the party’s seat allocation. The D’Hondt seat allocation rule implemented in Finland favors larger lists (Benoit, 2000). When looking at leadership positions, we should expect coalition parties to get a share of portfolios proportional to the seats they contribute to the coalition (Gamson, 1961). This means that small parties within a PEC could sometimes get important nominations that would usually be reserved for larger parties.Footnote 9

Finally, our novel key proposition is that PECs can be used as a way to influence whether a list obtains an absolute majority of seats. Obtaining an absolute majority in Finnish municipalities is critical as councils make decisions based on simple majority. Moreover, an absolute majority typically allows the winner to appoint both the board chairman (equivalent to the mayor of the municipality) and the council chairman (equivalent to the speaker of the local council). Avoiding this concentration of power might be driving many parties to coalesce. PECs might prevent a rival party obtain an absolute majority or might help coalescing parties reach such threshold.

4 Data and variables

This section describes the data that we use to study the causes and consequences of PECs. We use both party- and municipality-level data in the main text. In the supplementary materials, we additionally make use of dyadic data. These are discussed in detail in the Online Appendix.

4.1 Parties

The main body of our data consists of election results for all Finnish local elections held between 1996 and 2012, obtained from the Ministry of Justice. We report the detailed summary statistics on our data in Appendix Table A1. We restrict our analysis of PEC formation and their effects to registered political parties and rule out all independent (local) groups, because they are not allowed to form PECs.Footnote 10 We examine the votes and seats of all registered parties and obtain 11, 063 observations at the local party-election year level. Around \(16\%\) of observations are part of an electoral coalition.

We complement the election results with information from two data sources. First, we use data on the party of local political leaders (council and board chairmen) for the years 2000–2012 from the Finnish Association of Local Authorities (Kuntaliitto, 2013).

Second, we measure party ideology with the voting aid application (VAA) from the public broadcasting company YLE. VAAs are interactive online surveys that election candidates can fill before the election. Voters can then answer the survey and find the candidate who best matches their policy preferences. About 40% of Finnish voters use these surveys, so politicians are well incentivized to accurately represent their platform. Accordingly, Ilmarinen et al. (2022) show that the candidates responses are sincere rather than strategic by showing that candidates respond in the same way to a confidential survey as to the VAA.

Our VAA data come from the 2012 municipal election.Footnote 11 These data contain a number of questions related to the local public sector and answers to these questions from roughly half of the candidates. The contents of the voting aid application are largely related to the size of the public sector and redistribution, such as: “Privatizing public services makes them more efficient and saves money” and “We have paid too little attention to marginalization of children and teenagers”. A stronger agreement with the first claim is associated with a more right-leaning ideology, whereas the stronger agreement with the latter two claims is related to a more liberal ideology. Overall, the data contain seventeen claims. The candidates would give their answers on a 1–5 scale (from “completely disagree” to “completely agree” where the middle option was “I do not agree or disagree”).

We employ a principal component analysis to compress the survey responses into a single measure of economic policy preferences. This is a commonly used approach to extract a one-dimensional measure of ideology from survey data (Heckman & Snyder, 1997; Ansolabehere et al., 2001). See also Matakos et al. (2019) for further information and as an example of another study using these data. The first principal component captures the left-right dimension of economic ideology and explains about 15% of the variation in the data. We focus on this dimension of ideology, as it is more central for decision-making in local governments.

Online Appendix Table A2 reports results of the principal component analysis alongside with the questions included in our data. Claims where a stronger agreement implies more right-wing attitudes get larger positive values, whereas the opposite is true for claims where a stronger agreement is in line with more left-wing preferences. We multiply the resulting principal component by minus one in order to have a smaller score for left-wing parties. That is to say, the resulting ideology measure is the smaller the more liberal is a candidate.

To obtain an ideology score for each party, we average the resulting data by party—see Online Appendix Table A3 for summary statistics. While local party groups might be heterogeneous in terms of ideology (Debus & Gross, 2016; Gross & Debus, 2018), we believe that with the data we have at hand, using the nation-wide averages is a more reliable approach than constructing measures of local party ideology.Footnote 12 Importantly, there is considerable variation in response rates across local party groups. Using local-level ideology scores would mean that we would have to discard a large number of observations where a local party group has no respondents at all. Moreover, for many local party groups, the ideology scores would be estimated noisily using data from a small number of (possibly non-representative) respondents.Footnote 13

4.2 Municipalities

For some of our analyses, the unit of observation is at the municipality-election year level. We have 1914 such observations. In 692 of these cases, there is at least one PEC in the municipality. The municipality-level data serve us to test both the causes and consequences of PECs. When looking at the conditions under which PECs are more likely to form, our signaling hypothesis is easily tested with the number of parties in the municipality. We use the modified Gallagher index to capture disproportionality when we assess the disproportionality hypothesis (see Koppel and Diskin (2009)).Footnote 14 This measure captures the difference between the percentage of votes and the percentage of seats that each party receives. The larger the number, the more disproportional the representation in a particular municipality.

The level of political polarization at the local level might also influence the likelihood of coalitions. We measure ideological dispersion in municipalities at a point in time as follows: \(Polarization_{mt}=\sum _{p}v_{pmt}\left| x_{pmt}-{\hat{x}}_{mt}\right|\), were, \(v_{pmt}\) and \(x_{pmt}\) are the vote share and ideological position (respectively) of party p in municipality m at time t; \({\hat{x}}_{mt}\) is the vote-share weighted average of policy positions.

5 Causes of pre-electoral coalition formation

We start by evaluating how the characteristics of the political environment within the municipality shape coalition formation. This part of our empirical investigation is descriptive and complements and supports Golder’s work on PEC formation (Golder, 2005, 2006a). Because we are using municipality-level variables, our analysis deviates from that of Golder (2005, 2006a) who uses dyadic data to test for these hypotheses.Footnote 15 We use municipality-election year level data and OLS to estimate the connection between the presence of PECs and different variables characterizing the electoral conditions. We multiply the dependent variable by 100 so that the estimation results can be interpreted as percentages.Footnote 16

The results are summarized in Table 1. Consider first the signaling argument that suggests that an increase in the number of parties should be associated with an increased likelihood of having electoral coalitions. The coefficient of Number of parties is systematically positive and statistically significant, suggesting that having one more party is associated with an \(8-10\%\) increase in the probability that a municipality has a PEC. We further find support for a higher likelihood to form an alliance when the electoral system is more disproportional.Footnote 17

With large ideological differences, the incentives to obtain higher seat representation increase; thus, we should expect a higher likelihood of PECs. However, we do not find a significant positive correlation between the level of polarization and the propensity to coalesce. Contrary to Golder (2005), we do not observe that a disproportional electoral system should increasingly affect the likelihood of PECs when there are many parties in the municipality (column 2) nor when the municipality is very polarized (column 4).

6 Pre-electoral coalitions and electoral outcomes

We now zoom into political parties. We study two questions. First, what are the actual effects of joining a PEC at the party level? Second, do coalitions benefit or hurt political parties’ electoral performance?

6.1 Empirical strategy

We estimate a standard generalized differences-in-differences specification at the local party level:

Here \(PEC_{mpt}\) is a dummy for party label p belonging to a PEC in election t in municipality m, \(\alpha _{mp}\) is a local party label fixed effect (that is, a municipality times party fixed effect), \(\alpha _{t}\) is an election year fixed effect and \(\varepsilon _{mpt}\) is the error term. The estimate of our central interest is \({\hat{\beta }}\). It tells us the effect of forming a PEC on the outcome \(y_{mpt}\).

In this setting, the treatment group consists of those parties that switch from not having a PEC to having one, or from having PEC to not having one. The control group are those parties that maintain the status quo. The standard identifying assumption in a difference-in-differences strategy is that the outcomes in the coalescing parties would have evolved in the same way as before, had they not formed a PEC. Identically in this generalized setting, the outcomes of parties that had a PEC before, but that later dissolved it, would had evolved in the same way had they maintained the PEC. If this common trends assumption does not hold (e.g., because there are possibly unobservable, time-varying factors driving the PEC formation that also affect our outcomes of interest), the estimates ought to be treated just as conditional correlations.

One crucial time-variant factor that may shape both the outcome and propensity to join a coalition is party size: parties become less likely to coalesce the larger they are, but larger parties also tend to fare better in elections and the subsequent bargaining process. Thus, all our regressions control for party size, which we measure as the seat share the party obtained in the previous local election, \(\textit{Seat share}_{mp,t-1}\). We will return to the issue of parallel trends and time-variant confounders later in this article when discussing our robustness checks.

In order to analyze heterogeneous effects of electoral coalitions, we interact \(PEC_{mpt}\) with ideological differences within the coalition and the party p’s seat share in the previous election in some of our specifications. The former variable is simply computed as the distance between party p’s ideological position and the position of the party within the coalition that is most ideologically distant. Some of our analyses explore heterogeneity with respect to party size, again measured by \(\textit{Seat share}_{mp,t-1}\).

6.2 Estimation results

We report the party-level difference-in-differences results in Table 2. Perhaps surprisingly, we find that voters seem to punish parties for forming coalitions (column 1). This is at odds with the hypothesis that coalitions are formed for cost-sharing purposes which, in turn, should lead to an increase in coalescing parties’ vote shares as resources should be more efficiently used to target voters (Dhillon, 2003; Osborne & Tourky, 2008; Montero, 2016). Furthermore, this suggests that farsighted parties are not seeking votes when forming coalitions.Footnote 18

Our evidence also points towards ideological voting. On average, voters do not appear to punish coalescing parties that are ideologically similar yet punish parties that coalesce with ideologically distant parties (column 2).Footnote 19 The latter provides support for our theoretical argument that parties do not have incentives to coalesce with ideologically distant parties when voters are punishing this behavior.Footnote 20

Forming a coalition has a negative and statistically significant effect on seat shares (column 3)—though the effect is half the size of the effect on vote share. This suggests that the mechanical electoral economies of scale overcome to some degree the punishment that parties receive in terms of votes. This supports the argument that parties are more likely to form PECs in more disproportional elections. Once again, we see that the negative effect is concentrated on coalescing parties that are ideologically distant from each other (column 4).

Both results on votes and seats suggest that some parties might have a poor judgement when forming coalitions, as they do not seem to anticipate the negative consequences of such coalitions, in particular the ideologically asymmetric ones. Alternatively, parties might be strategically coalescing to influence the overall distribution of power in the municipality rather than seeking individual gains. We investigate this possibility in the next section.

In column (5), we see that joining a PEC—that is, in the Finnish case, forming a joint list with another party—leads to a less dispersed within-party personal vote distribution, using the Herfindahl index of the within-party personal vote shares as the dependent variable. The interaction between joining a PEC and party size has a negative effect on vote concentration, indicating that smaller parties within coalitions are the ones whose voters concentrate votes more.Footnote 21

Finally, we analyze the impact of forming a PEC in the assignment of leadership roles at the municipal level. Column (6) in Table 2 shows that coalescing large parties are less likely to obtain the top position in local government: the board chairmanship. This might be a sign of the concessions big parties need to commit to forge coalitions with smaller parties. Finally, column (7) shows instead that coalescing large parties are more likely to obtain the council chairmanship.

6.3 Robustness checks

In the Online Appendix, we document the robustness of these results to various sample restrictions and modeling choices. First, we study whether restricting the sample to parties that are part of an electoral coalition at some point of time matters for our results (Online Appendix Table B6). Parties that never join a PEC might be very different from those that join a PEC at least once.

Second, we assess the parallel trends assumption indirectly in two ways. We follow the estimation approach of de Chaisemartin and D’Haultfœuille (2020) which takes into account the staggered nature of our treatment and units moving between the treatment and control groups. Online Appendix Table B7 presents the main difference-in-differences estimates, and Figure B3 plots placebo estimates for two pre-treatment periods which can be conveniently estimated with the approach proposed by de Chaisemartin and D’Haultfœuille (2020). We see that the placebo estimates are not different from zero, which supports the validity of our empirical strategy. Note that estimating the interactions would be more challenging in this setup. Thus, we also rerun our estimations controlling for party-specific linear time trends to show underlying trends do not seem to be driving our estimates (Online Appendix Table B8).

Third, we estimate a model that includes additional covariates that account for endogenous candidate entry and potential trends in party popularity beyond what we can capture with the (lagged) seat share (Online Appendix Table B9). One possibility is that parties that previously competed independently may decide to join a PEC in response to a sharp decline in their popularity not captured by the lagged seat share. To tackle this concern, we include controls for candidates per seat and change in candidates per seat.Footnote 22 Candidate nomination happens close to the election date, in parallel with PEC formation, and the length of the party list likely correlates with the local popularity of the party. Including these controls does not affect our takeaways.

7 PECs and distribution of power in local councils

We do not seem to find evidence that being part of a PEC brings major electoral benefits to any party. However, there might be effects that are not observed at the individual party level. We conclude our empirical analysis by asking what are the effects of PECs at the municipal level. By doing so, we tackle our argument that PECs could affect the distribution of power and, most importantly, affect the likelihood of absolute majorities in the council.

7.1 Effects of PECs on municipality-level outcomes

We again estimate a difference-in-differences specification, yet now aggregating our data to the municipality-election term level. The regression central to our interest takes the following form:

\(PEC_{mt}\) is now defined as a dummy that is equal to one if there is a PEC in municipality m in election t. \(\delta _{m}\) and \(\delta _{t}\) are municipality and time fixed effects, respectively, and \(\mu _{mt}\) is the error term. Our estimation sample covers all municipalities that are observed at least twice.

Do PECs alter the number of parties that obtain representation in the municipality? Do they affect the concentration of the seat distribution in the municipality as captured by the Herfindhal Index? Do they influence the seat share of the biggest party in the municipality? Or do they change whether a party obtains an absolute majority of seats? All of these questions help us understand the overall distribution of power in the municipality and whether PECs have an effect on it.

Table 3 presents our results. When parties form PECs, the number of political parties represented in the local council increases by about 0.3 parties (column 1); political power becomes less concentrated (column 2); and, the largest party’s seat share decreases thus reducing the concentration of power on the most voted list (column 3). This last effect is rather small, about 0.8 percentage points, but recall that a small decrease could be crucial for some margins—in particular, the absolute majority threshold. Still, we do not find any significant evidence that PECs would make absolute majorities any less likely (column 4).

We present additional robustness checks in the Online Appendix. These support the parallel trends assumption and show that the estimation results remain largely unchanged when we follow the estimation procedure proposed by de Chaisemartin and D’Haultfœuille (2020).

7.2 Detailed analysis of close elections

While the reduction in the maximum seat share is quite small, it could be critical for the largest party to obtain an absolute majority in close elections. We address this possibility using a density discontinuity test. We follow an approach typically used in regression discontinuity design settings to test for potential manipulation of the running variable. To operationalize this test, we adapt the testing strategy proposed by Cattaneo et al. (2018, 2020) by implementing a robust bias-corrected density test. This means that we find a local polynomial fit for the density curve on both sides of the threshold and then calculate the jump in density at the cutoff point.

The density test results can be found in Table 4 which reports the density test statistics, associated p values, as well as a test for a difference in estimated discontinuities. A negative test statistic implies a jump downwards at the cutoff.Footnote 23 We conduct the test using different degrees of polynomials, and we also vary the window around the cutoff point.Footnote 24 We find that there is a downward jump in the density of maximum seat share at the \(50\%\) cutoff when there are PECs. Most of the density test results in the case of no alliances suggest no statistically significant jump at the threshold. Moreover, the density discontinuity test statistic is usually positive, unlike in the PEC sample. We also report the differences in discontinuities and test whether they are statistically significant. While the differences always have an expected (negative) sign, they are significant only for two of the specifications.

We then construct a placebo distribution of the largest party seat shares. We do so by taking municipalities that had PECs but distribute the seats according to the D’Hondt rule as if there were no alliances. The placebo distribution shows no hints of discontinuities close to the absolute majority threshold, as we verify more formally in Appendix B. This suggests that these PECs were able to prevent absolute majorities. As a further validity check, we explore covariate smoothness at the \(50\%\) seat share cutoff. We report these results in detail in Online Appendix Table B13.

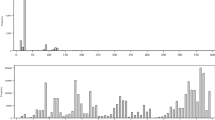

We visualize the key conclusion from the density discontinuity test in Fig. 3. The graph shows a non-parametric density fit under three scenarios: when there are no PECs (Panel A), when at least one PEC has been formed (Panel B), and a placebo test (Panel C). There is no jump at the cutoff when there are no PECs or when we look at the placebo distribution, but the density has a downward jump at the \(50\%\) seat share cutoff in municipalities that do have PECs.

Graphical illustration of the density discontinuity test. Notes: The figures show fitted distributions of the largest party’s seat share following the approach proposed by Cattaneo et al. (2018, 2020). The placebo seat shares in Panel C are calculated assuming that there were no PECs in municipalities where there actually are

8 Further lessons from dyadic data

As an additional “reality check,” we construct a dyadic data set comprised of all party pairs and examine which ones become actual coalition partners. We present our results and discuss them, as well as the data on party dyads, in detail in Online Appendix C.

Resonating with our main findings, we discover that (i) coalitions are formed to maximize the probability of obtaining an absolute majorities of seats but not expected coalition size per se, (ii) parties avoid asymmetric coalitions, and (iii) ideologically distant parties are less likely to coalesce. Recall that our party- and municipality-level data indicate that PECs hinder the formation of absolute majorities in close elections, size asymmetries within the coalition matter for strategic voting and the allocation of local political leadership positions, and in particular ideologically diverse PECs are punished by voters.

9 Discussion and concluding remarks

We study the logic of PEC formation and the effects of PECs on the distribution of political power. We begin by analyzing the process descriptively, but more importantly, we then provide some of the first causal evidence of the direct benefits and costs of forming PECs for political parties.

The different parts of our analysis are like matching pieces of a puzzle. First, the descriptive analyses reveal that PECs are more likely to occur (possibly to signal the intention for future cooperation) when there are more parties in an election. Analyzing the causal effects of PECs at the level of local governments shows that they, indeed, shape the distribution of political power and influence which parties govern. Second, we find evidence suggesting that parties are more likely to coalesce in more disproportional electoral environments. Looking at the vote and seat share effects of PECs helps us understand why. Third, the dyadic data that we analyze in the appendix show that size asymmetry and the likelihood of a PEC obtaining more than half of the seats matter as well. The party-level results offer a rationale for why parties avoid asymmetric coalitions: they are more prone to strategic voting. Fourth, the dyadic data show that PECs are less likely when parties are ideologically distant from each other. Additionally, the difference-in-differences results indicate that parties that join ideologically heterogeneous coalitions get punished by voters.

Taken together, our results indicate that coalition formation is not driven by purely vote-seeking motivations. Policy motivations appear to be more prevalent than the motivation to gain office, at least in part, because ideological proximity is an important determinant of PECs. Furthermore, PECs do not have a large impact on seat shares. Most importantly, we find that PECs affect the overall distribution of power by preventing absolute majorities from forming, thus ensuring that decision-making power is not concentrated.

Whether PECs should be allowed or not has been debated throughout the world. Some countries have even banned formal pre-electoral agreements. One argument against electoral coalitions has been that they may distort the electoral result and policies away from citizens’ preferences. However, our findings imply that PECs give parties an opportunity to guarantee a broader substantive representation of citizens’ policy preferences, by preventing absolute majorities.

Our results may help understand the strategic considerations behind PEC formation especially in PR elections with open or semi-open lists. Strategic parties can benefit from PECs in particular when they are formed between similar parties both in terms of ideology and size, and another party is close to gaining an absolute majority. In such cases, voter punishment is likely small and the mathematical electoral advantage of PEC may be enough to affect the distribution of power substantially. For instance, in the November 2023 parliamentary election in the Netherlands, the Social Democrats and the Greens will compete for the first time with a joint list. Echoing some of the theoretical arguments we make, the explicitly stated objective of this coalition is to hinder a majority of right-wing populists in the legislature. That said, PECs may play a different role in different electoral systems. This calls for more comparative research.

Our analysis also offers some lessons for thinking about the boundaries of political parties. The incentives created by the electoral rules and voter responses are similar when it comes to PECs or individual parties. Moreover, given that PECs are a very light version of collaboration, our results can be seen as a lower bound when compared to more intense and formal coalitions, party mergers, and party formation. For example, we can conjecture based on our results that voter ideology and electoral rules combine to create natural boundaries for the parties (Grofman, 2008; Matakos et al., 2019). Moreover, party formateurs are likely to consider how increasing or decreasing party boundaries affect the overall distribution of political power, not only the expected individual vote shares. Thus, our analysis provides some insights on what parties and party systems actually are, the performance of alternative electoral systems, and their implications for representation and voter satisfaction with democratic institutions. These are relevant questions especially in light of growing discontent with democratic politics around the world in recent years.

Notes

Even in the UK with a first-past-the-post system, there have been recent calls for a united front to defeat the Tories: “to defeat a common enemy, parties should set aside differences and cooperate.” See an editorial “The Guardian view on a progressive alliance: divided they fall” in The Guardian (December 13, 2020), available online at https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/dec/13/the-guardian-view-on-a-progressive-alliance-divided-they-fall (accessed January 20, 2021).

See an article in Helsingin Sanomat available at https://www.hs.fi/kotimaa/art-2000002575242.html (accessed March 11, 2020).

Municipalities have a very important role in the Finnish system. For instance, in our 1996–2012 data, they spend about 5500 euro per capita annually, on average (in 2012 prices).

About 64% of democracies employ a PR system, and a fourth of these use open-list procedures—see Scartascini et al. (2018).

The order of parties (or PECs) on the candidate list is determined by lottery. Similarly, the order of parties within a PEC is randomized. The norm is that candidates are presented alphabetically within party lists. Parties are allowed to move away from alphabetical order but this rarely happens.

See also Gschwend and Hooghe (2008) and Eichorst (2014) for examples of studies arguing that PECs provide cues to the voters with regards to the future government composition. Moreover, Gschwend et al. (2017) use a survey experiment to show that providing voters with coalition signals increases the importance of coalition considerations and decreases the importance of party considerations in voters’ decision-making.

In Finnish municipalities, there are typically no stable ruling government coalitions, indicating that small parties cannot access leadership positions via the post-electoral bargaining in exchange for agreeing to participate in a coalition government. However, Carroll and Cox (2007) propose a link between PECs and post-electoral bargaining outcomes. Similarly, Bandyopadhyay et al. (2011) present a formal model of PECs where parties can commit to seat-sharing agreements. They show that even ideologically distant parties may coalesce if there are potential post-electoral benefits of forming an electoral coalition. Christiansen et al. (2014), Debus (2009), and Eichorst (2014) also study the role of PECs in post-election bargaining.

This means dropping \(6.4\%\) of the local party-election year level observations. However, these observations are correctly accounted for in measurement when needs be, for example, when defining absolute majorities or number of parties. Independent groups comprise merely around \(3.4\%\) of all candidates.

Thus, we are unable to account for potential changes in parties’ ideological positions over time.

On the other hand, even in local elections, parties have national programs. It is likely that these programs are closely reflected at the local level of important issues that we can measure with the voting aid application data.

The respondents are younger than more often women than non-respondents. Respondents’ total vote shares and winning probabilities are also somewhat higher. This selection may lead to small amount of error in measuring party-level ideology even with the nationwide data, but these errors do not systematically concern any single party and are unlikely to impact our analysis.

The modified Gallagher index is formally defined as

$$\begin{aligned} Disproportionality_{mt}=\sqrt{\frac{1}{2} \times \sum _p \left( \frac{s_{pmt}}{\sqrt{\sum s_{pmt}^2}}-\frac{v_{pmt}}{\sqrt{\sum v_{pmt}^2}} \right) ^2, } \end{aligned}$$where \(s_p\) is the vote share of party p in municipality m at time t, and \(v_p\) is its vote share. Note that our analysis is not robust to considering the effective electoral threshold as a measure of disproportionality following Golder (2006a); see Online Appendix Table B4.

Given that the theoretical predictions concern the political context in the municipality instead of the characteristics of potential coalition partners, aggregated data is better-suited than dyadic data to this study.

We use OLS, as it is straightforward to interpret the estimation results as marginal effects. In Online Appendix Tables B2 and B3, we use probit and logit models, respectively, on a dummy outcome variable and obtain similar results.

Note that PECs affect the values that our disproportionality index gets. To avoid any biases that could arise from this, we use the lagged disproportionality metric in a robustness check—see Online Appendix Table B1. In the appendix, we also present and discuss results from a specification with municipality and year fixed effects which hold all time-invariant municipality-level characteristics and time-specific common shocks constant (Online Appendix Table B5.

Later in this section, we discuss the possibility that coalitions might form precisely because parties expected a lower than usual performance at the polls.

Online Appendix Figures B1 and B2 visualize the interaction effects.

The specifications that include \(\textit{PEC}\times \textit{Ideological range}\) do not contain the term \(\textit{Ideological range}\). By definition, there can be variation in this variable only when there is a PEC. It is not possible to include the interaction, an indicator for a PEC, and the constitutive term, as this would lead to multicollinearity issues.

This might also explain why PECs with asymmetric party size are not commonly observed. We find this when studying dyadic party data—see the penultimate section and Online Appendix C for further discussion.

It is possible that the number of candidates (per council seat) is a bad control, as the list size could also be affected by the choice to form (or to not form) a PEC. Therefore, we do not take this specification as our preferred one.

Formally, the test statistic is given by

$$\begin{aligned} T=\frac{{\hat{f}}_{+}({\bar{x}})-{\hat{f}}_{-}({\bar{x}})}{\sqrt{{\hat{\sigma }}_{+}^{2}+{\hat{\sigma }}_{-}^{2}}}, \end{aligned}$$where \({\hat{f}}_{+}({\bar{x}})\) and \({\hat{f}}_{-}({\bar{x}})\) are estimates of the density at the boundary point \({\bar{x}}\) and \({\hat{\sigma }}_{+}^{2}\) and \({\hat{\sigma }}_{-}^{2}\) are the standard errors of these estimates. Under certain conditions, the finite sample distribution of T can be approximated by the standard normal distribution.

We optimize the bandwidths in two alternative ways. We use either MSE-optimal bandwidths that vary on different sides of the cutoff, or restrict the bandwidth to be the same on both sides.

References

Allern, E., & Aylott, N. (2009). Overcoming the fear of commitment: Pre-electoral coalitions in Norway and Sweden. Acta Politica, 44, 259–285.

Ansolabehere, S., Snyder, J. M., & Stewart, C. (2001). Candidate positioning in U.S. house elections. American Journal of Political Science, 45(1), 136–159.

Bandyopadhyay, S., Chatterjee, K., & Sjöström, T. (2011). Pre-electoral coalitions and post-election bargaining. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 6(1), 1–53.

Benoit, K. (2000). Which electoral formula is the most proportional? A new look with new evidence. Political Analysis, 8(4), 381–388.

Blais, A., & Indridason, I. H. (2007). Making candidates count: The logic of electoral alliances in two-round legislative elections. Journal of Politics, 69(1), 193–205.

Carroll, R., & Cox, G. W. (2007). The logic of Gamson’s law: Pre-election coalitions and portfolio allocations. American Journal of Political Science, 51(2), 300–313.

Cattaneo, M. D., Jansson, M., & Ma, X. (2018). Manipulation testing based on density discontinuity. Stata Journal, 18(1), 234–261.

Cattaneo, M. D., Jansson, M., & Ma, X. (2020). Simple local polynomial density estimators. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 115(531), 1449–1455.

Christiansen, F. J., Nielsen, R. L., & Pedersen, R. B. (2014). Friendship, courting, and engagement: Pre-electoral coalition dynamics in action. Journal of Legislative Studies, 20(4), 413–429.

Cox, G. W., & McCubbins, M. D. (1993). Legislative leviathan: Party government in the house. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Cox, G. W., & McCubbins, M. D. (2005). Setting the agenda: Responsible party government in the U.S. House of representatives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

de Chaisemartin, C., & D’Haultfœuille, X. (2020). Two-way fixed effects estimators with heterogeneous treatment effects. American Economic Review, 110(9), 2964–96.

Debus, M. (2009). Pre-electoral commitments and government formation. Public Choice, 137(45), 45–64.

Debus, M., & Gross, M. (2016). Coalition formation at the local level: Institutional constraints, party policy conflict, and office-seeking political parties. Party Politics, 22(6), 835–846.

Dhillon, A. (2003). Political parties and coalition formation. Warwick economic research papers no. 697. http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/1491/.

Downs, A. (1957). An economic theory of democracy. New York, NY: Harper.

Duverger, M. (1954). Political parties: Their organization and activity in the modern state. New York, NY: Wiley.

Eichorst, J. (2014). Explaining variation in coalition agreements: The electoral and policy motivations for drafting agreements. European Journal of Political Research, 53(1), 98–115.

Fortunato, D. (2017). The electoral implications of coalition policy making. British Journal of Political Science, 49(1), 59–80.

Frey, A., López-Moctezuma, G., & Montero, S. (2021). Sleeping with the enemy: Effective representation under dynamic electoral competition. American Journal of Political Science (forthcoming).

Gamson, W. A. (1961). A theory of coalition formation. American Sociological Review, 26(3), 373–382.

Golder, S. (2005). Pre-electoral coalitions in comparative perspective: A test of existing hypotheses. Electoral Studies, 24(4), 643–663.

Golder, S. (2006a). Pre-electoral coalition formation in parliamentary democracies. British Journal of Political Science, 36(2), 193–212.

Golder, S. (2006b). The logic of pre-electoral coalition formation. Columbus: Ohio State University Press.

Grofman, B. (2008). The impact of electoral laws on political parties. In D. A. Wittman & B. R. Weingast (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of political economy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gross, M., & Debus, M. (2018). Gaining new insights by going local: Determinants of coalition formation in mixed democratic polities. Public Choice, 174(1), 61–80.

Gschwend, T., & Hooghe, M. (2008). Should I stay or should I go? An experimental study on voter responses to pre-electoral coalitions. European Journal of Political Research, 47(5), 556–577.

Gschwend, T., Meffert, M. F., & Stoetzer, L. F. (2017). Weighting parties and coalitions: How coalition signals influence voting behavior. Journal of Politics, 79(2), 642–655.

Heckman, J. J., & Snyder, J. M. (1997). Linear probability models of the demand for attributes with an empirical application to estimating the preferences of legislators. RAND Journal of Economics, 28, 142–189.

Ibenskas, R. (2015). Understanding pre-electoral coalitions in central and eastern Europe. British Journal of Political Science, 46(4), 743–761.

Ilmarinen, V. J., Isotalo, V., Lönnqvist, J. E., & von Schoultz, A. (2022). Do politicians’ answers to voting advice applications reflect their sincere beliefs? Comparing publicly and confidentially stated ideological positions in a candidate-centred electoral context. Electoral Studies, 79, 102504.

Koppel, M., & Diskin, A. (2009). Measuring disproportionality, volatility and malapportionment: Axiomatization and solutions. Social Choice and Welfare, 33(2), 281–286.

Kuntaliitto. (2013). Kuntien luottamushenkilötilasto.

Levy, G. (2004). A model of political parties. Journal of Economic Theory, 115(2), 250–277.

Matakos, K., Savolainen, R., Troumpounis, O., Tukiainen, J., & Xefteris, D. (2019). Electoral institutions and intraparty cohesion. VATT working papers no. 109. https://www.doria.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/159572/WP109.pdf?sequence=5.

Meriläinen, J. (2019). Single-party rule, public spending, and political rents: Evidence from Finnish municipalities. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 121(2), 736–762.

Meriläinen, J., & Tukiainen, J. (2018). Rank effects in political promotions. Public Choice, 177, 87–109.

Meriläinen, J., & Tukiainen, J. (2022). The advantage of incumbents in coalitional bargaining. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 47(4), 921–957.

Montero, S. (2016). Going it alone? An empirical study of coalition formation in elections. Working paper. https://www.sas.rochester.edu/psc/smontero/going_it_alone.pdf.

Osborne, M. J., & Tourky, R. (2008). Party formation in single-issue politics. Journal of the European Economic Association, 6(5), 974–1005.

Parigi, P., & Bearman, P. S. (2008). Spaghetti politics: Local electoral systems and alliance structure in Italy, 1984–2001. Social Forces, 87(2), 623–649.

Powell, G. (2000). Elections as instruments of democracy: Majoritarian and proportional visions. Yale: Yale University Press.

Scartascini, C., Cruz, C., & Keefer, P. (2018). The database of political institutions 2017 (DPI2017). https://publications.iadb.org/en/database-political-institutions-2017-dpi2017.

Acknowledgements

We thank an anonymous referee, the associate editor (Ennio E. Piano), Catarina Alvarez, Torun Dewan, Olle Folke, Zhen Im, Theodora Helimäki, Åsa von Schoultz, Stephane Wolton, and the audiences at University of Helsinki, University of Turku, EPSA 2017, and IIPF 2021 for useful comments and discussions.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Stockholm School of Economics.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hortala-Vallve, R., Meriläinen, J. & Tukiainen, J. Pre-electoral coalitions and the distribution of political power. Public Choice 198, 47–67 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-023-01109-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-023-01109-1

Keywords

- Coalition formation

- Local elections

- Multi-party systems

- Open-list proportional representation

- Pre-electoral coalitions