Abstract

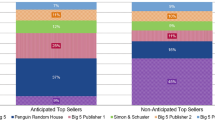

This experiment shows how different levels of fines in three antitrust policies—no leniency (NL), standard leniency (LP), and amnesty plus (AP)—can deter multimarket cartels. With a low fine, AP significantly increases multimarket cartels and leads to higher prices. With a high fine, it has the same effect on collusion as do other policies. With regard to one-market cartels, AP decreases cartel stability relative to LP. With a high fine, it leads to more reporting than does LP, before any investigation and after a first cartel conviction. Higher fines also lead to higher prices in NL and LP, but not higher than in AP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Examples of such cartels are numerous: For instance, in 2018, the European Commission penalized automotive suppliers—including Bosch and Continental—for participating in the exchange of sensitive business information in two markets. The American company TRW—which was a member of one cartel—was granted leniency for having reported it. In the other cartel, only Bosch was fined, as Continental was granted leniency.

This is sometimes also referred to as Leniency Plus.

See notably this report from the US Department of Justice: https://www.justice.gov/atr/file/518156/download.

The full list of countries that offer Amnesty/Leniency Plus is well detailed in Martyniszyn (2015).

Note that on a theoretical basis, we also extend the analysis of Lefouili and Roux (2012) to the case with no leniency but with a standard antitrust policy (NL).

One has to keep in mind, though, that in their paper, an increase in the fine was offset by a reduction in the probability of detection.

We believe that this situation is more realistic in terms of market competition. Moreover, having a situation in which the subjects of the experiment have a zero profit in a competitive situation can lead to behavioral biases: First, having a boundary equilibrium may result in biased observations if the subjects make errors, as errors can go in only one direction. Second, from a psychological viewpoint, the subjects might be reluctant to choose a price that results in 0 profits, as they usually participate to make money. This paradigm shift necessarily induces changes with respect to the thresholds that are defined in Lefouili and Roux (2012), which we characterize according to our parameters.

There is indeed a great deal of theoretical work on the analysis of leniency programs; see notably Motta and Polo (2003); Brisset and Thomas (2004); Aubert et al. (2006); Motchenkova and van der Laan (2011); Harrington (2013); Sauvagnat (2014); Houba et al. (2015); Sauvagnat (2015); and Blatter et al. (2018).

The only implication under standard leniency of the existence of two markets is that having one market discovered increases the probability that the other one is detected as well.

We could also cite Hamaguchi et al. (2009) on the precise question of the effect of group size on the formation of cartels.

Indeed, most previous experimental papers on a single market point out that NL leads to the formation of more cartels than LP and may have a pro-collusive effect, but it is not clear that this is always true with two markets. On the other hand, NL could potentially be less pro-collusion than is AP by also leading to a suppression of the second cartel in the event of detection of the first one, without the need for a fine cancellation of both cartels, decreasing the expected collusive profit in comparison with AP.

Assuming that AP leads to a full cancellation of the fine for the first detected cartel is a strong assumption, even if (to our knowledge) it is applied in South Korea. Nevertheless, we make this assumption in order to maximize the gap between AP and LP and to simplify the experiment.

It should be noticed that we introduced an important simplification in our protocol: As soon as one player deviates or reports in one market, then collusion in both markets in the subsequent periods becomes no longer possible through to the end of the match. Thus, in this situation, subjects choose only prices in each period – and the AA may still detect a cartel from the previous period), until the match ends.

In this case, as in Hamaguchi et al (2009), players start from a situation where it is considered that two cartels have already been formed and one cartel has already been detected. Thus, the first decision players have to make in the first period of each match is whether or not to report the second cartel. The game then proceeds normally to subsequent periods. See the online instructions for more details: Supplementary file1 or https://crese.univ-fcomte.fr/uploads/fichiers/2a2105977277ea66814a036fb472bd19.pdf.

Despite all of these precautions, subjects failed to make a communication choice in about 2.0% of the cartels and failed to choose a price in about 1.1% of the markets; these cases are not taken into account in the analysis.

We elicited the participants’ risk attitude at the end of the experimental session through two means: First, we implemented a lottery-choice task, where participants must make 11 decisions between risky and safe lotteries: the risky lottery brings either 5 € or 0 € with a probability of 50% each, whereas the safe lottery provides the subject with an amount that increasing from zero to 5 €. Second, risk aversion was also elicited through a simple question that was asked at the end of the session within a post-experimental questionnaire: “Please indicate on a scale from 0 to 10 where you think you stand, with 0 representing someone who loves to take risks and 10 representing someone who is extremely cautious.” The results obtained with both measures are positively correlated. The lottery-choice task is more complex, and many subjects seemed to have a hard time understanding it (it was run at the end of rather long sessions). Thus, we used the latter risk aversion index in the econometric analysis that is presented in this article. However, our conclusions remain unchanged if we use the former risk-aversion variable.

Here we focus on the cartel incidence, which is the result of the individual “willingness to form cartels” of both firms. It should be noticed that running the analysis on these individual decision variables result globally in qualitatively similar results. Nevertheless, we may have fewer cartels in only one market because of coordination problems due to the simultaneity of communication decisions for each market (in concordance with the theoretical model).

These percentages are very close to Bigoni et al. (2012).

Behavioral explanations—such as quantum response equilibrium (QRE)—could also explain the fact that prices can be higher than the Nash equilibrium under Bertrand competition; see, for example, Fatas et al. (2014).

References

Andres, M., Bruttel, L., & Friedrichsen, J. (2021). The leniency rule revisited: Experiments on cartel formation with open communication. International Journal of Industrial Organization. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijindorg.2021.102728

Apesteguia, J., Dufwenberg, M., & Selten, R. (2007). Blowing the whistle. Economic Theory, 31, 143–166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00199-006-0092-8

Aubert, C., Rey, P., & Kovacic, W. E. (2006). The impact of leniency and whistle-blowing programs on cartels. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 24(6), 1241–1266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijindorg.2006.04.002

Bigoni, M., Fridolfsson, S. O., Le Coq, C., & Spagnolo, G. (2012). Fines, leniency and rewards in antitrust. The RAND Journal of Economics, 43(2), 368–390. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-2171.2012.00170.x

Bigoni, M., Fridolfsson, S. O., Le Coq, C., & Spagnolo, G. (2015). Trust, leniency, and deterrence. Journal of Law, Economics and Organization, 31(4), 663–689. https://doi.org/10.1093/jleo/ewv006

Blatter, M., Emons, W., & Sticher, S. (2018). Optimal leniency programs when firms have cumulative and asymmetric evidence. Review of Industrial Organization, 52(3), 403–427. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11151-017-9586-8

Brisset, K., Cochard, F., & Lambert, E. A. (2019). Lutte contre les cartels multimarchés: Une comparaison expérimentale des programmes de clémence Américain et Européen. Revue Economique, 70(6), 1171–1185. https://doi.org/10.3917/reco.706.1171

Brisset, K., & Thomas, L. (2004). Leniency program: A new tool in competition policy to deter cartel activity in procurement auction. European Journal of Law and Economics, 17(1), 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026329724892

Choi, J. P., & Gerlach, H. (2012a). Global cartels, leniency programs and international antitrust cooperation. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 30, 528–540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijindorg.2012.05.005

Choi, J. P., & Gerlach, H. (2012b). International antitrust enforcement and multimarket contact. International Economic Review, 53(2), 635–657. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2354.2012.00695.x

Choi, J. P., & Gerlach, H. (2013). Multimarket collusion with demand linkages and antitrust enforcement. Journal of Industrial Economics, 61(4), 987–1022. https://doi.org/10.1111/joie.12041

Dijkstra, P. T., Haan, M. A., & Schoonbeek, L. (2021). Leniency programs and the design of antitrust: Experimental evidence with free-form communica- tion. Review of Industrial Organization, 59, 13–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11151-020-09789-5

Fatas, E., Haruvy, E., & Morales, A. J. (2014). A psychological reexamination of the Bertrand paradox. Southern Economic Journal, 80(4), 948–967. https://doi.org/10.4284/0038-4038-2012.264

Fischbacher, U. (2007) z-Tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Experimental Economics, 10, 171–178

Hamaguchi, Y., Kawagoe, T., & Shibata, A. (2009). Group size effects on cartel formation and the enforcement power of leniency programs. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 27, 145–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijindorg.2008.05.005

Harrington, J. E. (2013). Corporate leniency programs when firms have private information: The push of prosecution and the pull of pre-emption. Journal of Industrial Economics, 61(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/joie.12014

Hinloopen, J., & Soetevent, A. R. (2008). Laboratory evidence on the effectiveness of corporate leniency programs. The RAND Journal of Economics, 39(2), 607–616. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0741-6261.2008.00030.x

Houba, H., Motchenkova, E., & Wen, Q. (2015). The effects of leniency on cartel pricing. The B.E. Journal of Theoretical Economics, 15(2), 351–389. https://doi.org/10.1515/bejte-2013-0139

Jans, I., & Rosenbaum, D. I. (1997). Multimarket contact and pricing: Evidence from the U.S. cement industry. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 15, 391–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-7187(95)00493-9

Khwaja, A., & Shim, B. (2017). The collusive effect of multimarket contact on prices: Evidence from retail lumber markets. In 2017 Meeting Papers (Vol. 593).

Lefouili, Y., & Roux, C. (2012). Leniency programs for multimarket firms: The effect of amnesty plus on cartel formation. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 30, 624–640. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijindorg.2012.04.004

Martyniszyn, M. (2015). Leniency (amnesty) plus: A building block or a trojan horse? Journal of Antitrust Enforcement, 3(2), 391–407. https://doi.org/10.1093/jaenfo/jnv005

Marx, L. M., Mezzetti, C., & Marshall, R. C. (2015). Antitrust leniency with multiproduct colluders. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 7(3), 205–240. https://doi.org/10.1257/mic.20140054

Motchenkova, E., & Van der Laan, R. (2011). Strictness of leniency programs and asymmetric punishment effect. International Review of Economics, 58(4), 401–431. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12232-011-0131-z

Motta, M., & Polo, M. (2003). Leniency programs and cartel prosecution. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 21, 347–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-7187(02)00057-7

Parker, P. M., & Roller, L. H. (1997). Collusive conduct in duopolies: Multimarket contact and cross-ownership in the mobile telephone industry. The RAND Journal of Economics, 28(2), 304–322. https://doi.org/10.2307/2555807

Radoc, B., Libre, P.A. , & Prado, S.A. (2020). Incentive to squeal: an experiment on leniency programs for antitrust violations. WP 2020–03 Ateneo Center for Economic Research and Development.

Sauvagnat, J. (2014). Are leniency programs too generous? Economics Letters, 123(3), 323–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2014.03.015

Sauvagnat, J. (2015). Prosecution and leniency programs: The role of bluffing in opening investigations. Journal of Industrial Economics, 63(2), 313–338. https://doi.org/10.1111/joie.12072

Spagnolo, G. (2008). Leniency and whistleblowers in antitrust. MIT Press.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants of the AFED (2018), EALE (2019), JMA (2019), LAGV (2019), ASFEE (2021), and ESA (2021) for useful feedback. We are very grateful to two anonymous referees and to the editors of this special issue and of this journal for their relevant suggestions that helped us greatly to improve the article. This research has been made possible by financial support from the Region Lorraine (now in Region Grand-Est), the CRESE, the University of Franche-Comte and the University of Lorraine.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed equally to this work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Brisset, K., Cochard, F. & Lambert, EA. Is Amnesty Plus More Successful in Fighting Multimarket Cartels? An Exploratory Analysis. Rev Ind Organ 63, 211–237 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11151-023-09919-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11151-023-09919-9

Keywords

- Antitrust

- Multimarket cartels

- Leniency programs

- Leniency plus

- Price competition with differentiated products