Abstract

To date, no empirical study has examined the impact of negative gearing and other factors on residential investors’ decisions using quantitative analysis. We applied a structural vector autoregression framework to trace the response of residential investors in Greater Sydney to shocks in its key drivers over the period 1991–2018. We discovered a residential investors’ profile in which negative gearing is being used to cushion any net rental loss during periods of low yield while expecting capital growth over their holding period. This supports the hypotheses of the study which posit that capital gains and negative gearing have a positive and negative relationship, respectively, with the number of residential investors. Additionally, a negative relationship between mortgage lending rate and number of investors is found, indicating a rising lending rate will increase expenses and contribute to low yield. We also found population growth and increased housing supply could increase the number of residential investors. These results could be used by tax and housing policy makers to recalibrate tax laws relating to negative gearing, especially for residential investment. Residential investors could potentially use this information for more informed decision making, particularly during periods of low yields.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

As homeownership is becoming more challenging in most developed nations (Bangura & Lee, 2023), the private rental market continues to expand (Pawson et al., 2019). This makes housing a great form of investment for many households (Krever & Sadiq, 2019; Ley, 2017). In Australia, for example, households accounted for more than 60% of investment in residential properties (Lee 2017). This raises the question as to the behaviour of investors in the housing market and what fundamental factors drive their decisions. Key to this is the issue of negative gearing and other related factors impacting the investment decisions of residential investors. Circumstances of negative gearing would arise when a leveraged asset, such as a rental property, cannot produce enough income to meet its interest payment and other related property expenses. A comparison of tax laws relating to negative gearing shows diversity in its application across advanced nations. While negative gearing is being phased out in countries such as the United Kingdom and New Zealand, it is still applicable in countries like Australia, Canada, and France though with varying magnitude (Duncan et al., 2018). Across these nations, Australia’s negative gearing is the most generous to leveraged investors (Daley and Wood 2016). The Assistant Governor (Economic) of the Reserve Bank of Australia [RBA], Ellies (2006), earlier reiterated the generosity of negative gearing towards individual housing investors as it allows these investors to negatively gear expenses against other income. In July 1985, the Australian Government prohibited the use of rental property loss to lessen tax liability on other assessable incomes. However, this was short-lived as it was reversed in July 1987 on the grounds that it would push up rental prices. Since then, negative gearing has been applied in property and other types of investment (Bloxham et al., 2011; Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia [PCoA], 2016).

Other studies have also highlighted the importance of yield in influencing residential investors’ decisions (Huang et al., 2018). Newell et al. (2015) pointed out the role of house price appreciation, while Chang et al. (2011) and Lowies et al. (2015) identified population, the level of economic activity, interest rate, and housing supply as critical drivers of residential investment decisions. However, the broad spectrum of these studies is generally largely narrative, and in some cases, descriptive statistical methods are employed. An exception is Choy et al. (2011), but this is an aggregated study. Thus, the findings of these studies are somewhat mixed. This divergence in the literature triggered the argument on how residential investors’ decisions are impacted by these factors. So far, no study has empirically scrutinised the link between these factors and residential investment activities at the sub-national level, especially in the context of a developed market. Noting the critical role of negative gearing and other factors in the residential investment setting, this is the first dedicated study to empirically test the impact of these factors on residential investors’ decisions at a sub-national level, namely, the Greater Sydney housing market. Greater Sydney, unlike other Australian cities, is characterised by high housing investors’ activities. For instance, the share of investor loan approvals has soared from almost 30% in 2011 to close to 40% in recent times with the state of New South Wales (NSW) accounting for the biggest increase (Reserved Bank of Australia [RBA], 2015). As of October 2020, for example, 42% of the total number of housing investors in Australia were in NSW, with a large proportion of this investment in Greater Sydney. During the same period, A$2.435 billion was committed in new loans for housing investment in NSW, accounting for 46% of new loan commitment for investors in Australia (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], 2020a). This makes Greater Sydney an ideal case study for this analysis.

We employed a structural vector autoregression (SVAR) to examine residential investors’ decisions and documented the following findings. This is the first empirical study to perform a quantitative analysis of the impact of negative gearing and other factors on residential investors. We found residential investors are willing to accept low housing yield due to the possible use of negative gearing in the tax system while also benefiting from capital gains over time. In other words, during periods of expected growth in return, we would likely see low yields and a relatively high number of investors. Evidence of a positive relationship between the number of residential investors and capital gains, and an inverse relationship between yield and the number of residential investors support the hypotheses of the study. These findings have highlighted an important feature of residential investors as they use negative gearing to lessen any loss during periods of low yields while expecting capital growth over their holding period. These results could be used by tax and housing policy makers to recalibrate their tax laws relating to negative gearing. The leveraged residential investors could use this information for more informed decision making, especially during periods of low yields.

Second, this study is the first to examine other important drivers of residential investors at a sub-national level. As expected, we found an inverse relationship between mortgage lending rate and the number of investors, indicating that higher lending rate will increase investment expenses, and this will increase the chances of low yield. Circumstances of rising mortgage lending rate further explain the profile of residential investors as they expend more in their investment and utilise negative gearing to minimise the effect of any loss arising from their investment. The direct relationship between housing supply and the number of residential investors, and the inverse relationship between population and the number of residential investors show both supply-and-demand sides of the housing market can potentially promote residential investment. This certainly explains the growing number of household investment in residential properties. The findings on mortgage lending rate could be used by financial policy makers in the design of monetary policies to regulate the economy. More specifically, the finding could be useful in situations where the housing market is expected to revitalise the economy. The results of housing supply could inform policy makers seeking to maintain a balance between homeownership and residential investment amid an almost perfectly inelastic housing supply.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides a brief profile of the study city, while Sect. 3 reviews the related literature and the conceptual framework of the study (or the hypotheses). The data and methodology are discussed in Sect. 4. Section 5 presents the results, and Sect. 6 outlines the concluding statements of the study.

2 Brief profile of Greater Sydney

Greater Sydney has been the capital of the state of New South Wales (NSW) since 1901 when Australia became a federation. In terms of geography, Greater Sydney extends from Wyong and Gosford in the north to the Royal National Park in the south and follows a shoreline in between. Located in the west end of the city are the Blue Mountains, Wollondilly, and Hawkesbury municipalities. The city covers 12,368.7 square kilometres, and it is made up of 35 local municipalities (City of Sydney [CoS], 2023).

Greater Sydney is the most populous metropolitan city in Australia over the past two or more decades. This accounts for the steady increase in demand for residential property investment in this city over the years (Birrell & Healy, 2013; Milligan et al., 2013; Valadkhani & Smyth, 2017). Table 1 shows the estimated resident population of Greater Sydney from 2016 to 2021 using data collected from ABS, (2023). Throughout this period, Greater Sydney is home to almost 65% of people residing in the state of NSW. At a national level, Greater Sydney is home to at least one in every five residents of Australia. The annualised population growth rate of Greater Sydney between 2016 and 2021 was 1.92% which is greater than the 1.21% growth rate of Australia. This consistent growth in the population of Greater Sydney comes with diverse opportunities and challenges in the housing market.

From the economic and employment viewpoints, Greater Sydney is generally regarded as the financial and business services hub of Australia, with an intensity of jobs in the service sector of the economy. Specifically, more than 75% of all foreign and domestic banks in Australia are headquartered in Sydney (Bangura & Lee, 2023). Moreover, there is a general disparity in the nature of jobs across the city with the most common sector of employment, as of 2016, being Health Care and Social Assistance with 11.8%. This is followed by Professional, Scientific and Technical Services with 10.2%, Retail with 9.7%, and Education and Training with 8.3% (CoS, 2023). There is also a job disparity across regions with a concentration of high value, knowledge-intensive industries such as IT, finance, engineering, healthcare, research, marketing, and media jobs in the eastern and northern regions of the city, while manufacturing, warehousing, education, social and transport services predominantly cluster in the western region of the city. In the 2018/2019 financial year, Greater Sydney’s contribution to Australia’s GDP was over $460 billion, accounting for nearly 25% of the country’s GDP (Cos, 2023).

Globally, taking into consideration the city’s social, economic, environmental, and cultural indicators, Greater Sydney has been constantly ranked among the 10 most connected cities. The Loughborough University's globalisation and world cities research network, which measures the connectivity of cities in terms of position and influence, ranked Greater Sydney in the top 10 band alongside London, New York, Tokyo, Paris, and Hong Kong. The 2020 Anholt-Ipsos City Brand Index ranked Sydney as the second-best city in the world for its brand appeal and image that capture physical looks, international status and standing, standards of housing and public amenities, and economic and educational opportunities. In terms of global competitiveness across international finance, in 2020, Greater Sydney made it into the top 20 list of leading centres and was ranked eighth overall in the Asia–Pacific region.

3 Literature review and hypothesis development

3.1 Literature review

First, we review the literature on rental and investment in residential properties with a focus on the two major classes of residential investors—household and institutional. This is followed by a review of the literature on the drivers of residential investment.

Previous studies like Brown et al. (2008), Milligan et al. (2013), Newell et al. (2015), and Lee et al. (2017) have offered significant evidence of household dominance in residential property investment in Australia. Lee (2017), for example, found that almost two-thirds of residential property investors do so for long-term purposes. In terms of the rental housing stock, Hulse et al. (2012) found that nearly 80% of Australian rental properties are largely owned by small and individual investors. Kohler and van der Merwe (2015) previously highlighted that housing investment not only constituted a large proportion of household wealth in Australia, but small business loans are also secured against residential investment, accounting for a significant portion of the collateral backing of the financial sector. On the other hand, several studies have reported the shallow interest being expressed by institutional investors in residential property investment in Australia. Milligan et al. (2013) and Newell et al. (2015) identified low yields, stamp duty and relevant land taxes, and high level of various risks, as disincentives to institutional investors in the rental housing market. However, in countries such as Japan and the USA, there is evidence of significant investment in residential properties by institutional investors (Lin et al., 2019).

The expectations of strong growth of residential prices in the future have triggered a rise in investors demand for residential properties (Reserve Bank of Australia [RBA], 2013). As pointed out by Pawson and Martin (2020), the hope of huge capital gains is a motivating factor for many residential investors in the low-income Western Sydney region. Similarly, Soaita et al. (2017) found that the investment decisions of many residential investors are influenced by capital gains, a conclusion that was earlier reiterated by Forlee (2015) and Goetzmann et al. (2012). Several studies, such as Chen et al. (2014), Wang et al. (2013), Obereiner and Bjorn-Martin (2012), have also shown that the expectation of house price appreciation could be used for inflation hedging purposes. However, an increase in default rate is likely to reduce the appreciation of house prices (Hayunga et al., 2019).

Housing yield is also a critical factor in residential investment. Tipping et al. (2015) found that housing yield is playing a cardinal role in shaping residential property investment decisions. Housing yield generally denotes the degree of attractiveness and, in some cases, offers a benchmark for residential investment (French & Patrick, 2015). As such, an increase in investors' required property asset yield would often lead to a reduction in property prices and the scope of new development (Henneberry & Mouzakis, 2014). This is supported by Cajias (2019) who found that investors in the largest and most appealing cities of Germany receive the lowest yields as house prices show stronger growth than rent in these cities. This can be attributed to the burden of mortgage and long-term growth in rent (Huang et al., 2018). Other studies such as Grudnoff (2015) and Blunden (2016) noted that lower housing yield would mean investors can capitalise on negative gearing and subsequently gain from the appreciation of property prices over time in countries where investors can claim negative gearing.

The literature on other drivers of residential investment also exists. Das et al. (2015) found housing supply activities to be significantly and directly linked to residential investment. More broadly, Chu and Sing (2004) found GDP growth rate to be statistically insignificant in explaining the variation in real estate investments, while a positive effect of economic activities on residential investment is found by Corder and Roberts (2008) and Saunders and Tulip (2019). Similar results were reported by Henneberry and Mouzakis (2014) who found the interest rate and the performance of the national economy to be major drivers of local property market cycles and trends. Belke and Keil (2018) reiterated that interest rate is fundamental in making residential investment decisions as a rising interest rate is expected to slow down investment due to the heavy burden of financing the property loan. Wood and Ong (2013a) and Chang et al. (2011) each asserted the role of fiscal and monetary policy framework in shaping rental housing investment decisions. Choy et al. (2012) reported the varying effects of population, income, GDP activities, interest rate, and housing supply activities on residential investment across the regions of China.

So far, in Australia, the literature has revealed that residential investment is done mostly by households. However, as discussed by Newell et al. (2015), individual investors have a different consideration of housing yield compared with institutional investors. This is due to the tax implications of negative gearing and capital gains discount (Pawson et al., 2020). Previous studies also contextualise expectation of strong capital growth and other market fundamentals in residential investment decisions. However, the gap in the literature is the quantitative analysis of how these factors would affect residential investment decisions especially at the sub-national level. To delve into this gap, in the next sections, we discuss negative gearing to lay out the theoretical framework and develop the basis of the study hypotheses.

3.2 Negative gearing and housing investment activities

There is heightened topicality around negative gearing in the discourse on property investment in several advanced economies including Australia. In a recent publication by the Commonwealth Bank of Australia [CBA] (2023), gearing in the context of property investment is the use of a loan to finance a property asset. The rental income earned from the investment can be positively or negatively geared, and this has significant tax implications. The investment is negatively geared when the rental income is below the interest payments and other property-related expenditures. This allows the investor to offset any net rental loss incurred during the financial year against other income earned, such as wages and salaries. Consequently, it will reduce the taxable income and the incidence of tax to the investor (CBA, 2023). This circumstance allows investors but not homeowners to offset their income with losses from their investment properties (e.g., rental losses).

Negative gearing in property investment has wider and diverse applications across nations. In Australia, investors can deduct their entire net loss on negatively geared assets such as stocks and residential property against other types of income including salaries and business revenue. There are no restrictions on the types and number of assets held by the investor, and there is also no limit in the value of losses in any given year (Bloxham et al., 2011; Grudnoff, 2018). In the 2012–2013 income year, for example, statistics from the Australian Treasury revealed that out of the 1.9 million recipients of rental income, around 1.3 million reported a net rental loss (Australian Treasury Department, 2014). In the 2015–2016 financial year, Blunden (2016) found three out of five Australian residential investors claimed a net rental loss and utilise negative gearing. The benefits of negative gearing together with capital gains tax discount generated about A$7.7 billion for housing investors with the largest share going to wealthy investors (Grudnoff, 2015). A few years later, Grudnoff (2018) found that high-income households are the major beneficiaries of negative gearing with the top 20% of households taking about 50% of these benefits. More specifically, in the 2014–2015 financial year, for example, higher-income residents of northern and eastern regions of Greater Sydney were among the taxpayers who claimed the highest loss of rental income that was negatively geared in Australia (PCoA, 2016; Grudnoff, 2018).

Conversely, in the United Kingdom, previously, if an investor makes a loss on an asset in a given financial year, the loss is quarantined to that asset class only. Further, if the investor is still in an overall net loss position for that financial year after deducting the income losses in that investment against the gains in that same asset class, they can carry forward and utilise the remaining losses in future financial years. The investor can also offset any unapplied losses against the capital gain realised when the asset is sold (Beckett, 2014). However, this tax incentive has been mostly phased out as of the 2020–2021 financial year (Duncan et al., 2018). In several EU nations, such as the Netherlands, there has been a discontinuation or some form of reduction in mortgage interest tax deductibility (Frayne et al., 2022). In New Zealand, prior to the amendment of the country’s Income Tax Act of 2021, negative gearing was the largest and most widely used tax rebate among rental property investors which reduces their taxable income from other income sources. However, the 2021 amendment abolished negative gearing for all future purchases and put in place a five-year phase-out plan for existing leveraged property investment (Rehm & Yang, 2021). In Canada, negative gearing is limited to cash outlays only, while in France it is capped. The negative gearing in the USA does not allow against labour income (Duncan et al., 2018).

The international comparison of tax regimes shows a variation in the application of negative gearing, a situation that has triggered several perspectives about the role of this tax policy in the housing market. In Australia, Bloxham et al. (2011), David and Soos (2015), and Grudnoff (2018) argued that most residential investors do so to seize the advantage of negative gearing. This has stimulated a broader application of this tax incentive in property and other types of investment (Bloxham et al., 2011; PCoA, 2016). The rationale underpinning this tax policy is that these incentives would encourage investment in housing construction to boost housing supply and reduce the pressure on housing rent (Pawson, 2018). Another school of thought articulated by Frayne et al. (2022) and Turk (2015) proffers that tax deductibility can increase housing prices and cause more volatility in the housing market. They further argued that such tax policy can reduce home ownership by crowding-out households that are financially constrained. Further, Daley and Wood (2016) reported the revenue loss associated with negative gearing in Australia, citing a boost of $2 billion, will be realised in government revenue a financial year with the removal of such tax policy. This reveals that Australia’s treatment of rental property losses is the most generous when compared to other countries including the United Kingdom and the USA (Daley and Wood 2016).

3.3 Theoretical framework and hypotheses development

The previous sections highlighted the literature on the motivating factors of housing investment decisions and negative gearing. As stated earlier, most of these studies are narrative and none has empirically tested how shocks in these factors could affect housing investors, especially at the submarket level. Again, some studies have identified house price appreciation as a key influencer of residential investment decisions (Soaita et al., 2017; Pawson and Martin 2020). This is grounded on the notion that residential investors would normally expect an increase in house prices over time (Bjorn-Martin 2012; Wang et al., 2013). This is reiterated in Bangura and Lee (2020, 2022) who argued that speculative investors are more likely to focus on housing price appreciation. Further, in Australia, housing investors would be eligible for a 50% discount on their capital gain if they hold their investment properties for more than 12 months. This suggests these residential investors are more likely to resell their investment property after a year if capital gain is their main consideration. Premised on this discussion, we advance the first hypothesis of the study:

Hypothesis 1

There is a positive link between housing investors’ activities and housing price appreciation.

In Australia, however, as discussed in Sect. 3.2, housing investors also benefit from another tax incentive known as negative gearing. Again, negative gearing allows investors but not homeowners to offset their income with losses from their investment properties (e.g., rental losses). The introduction of negative gearing, to a certain extent, does encourage investors to hold a property for a longer time horizon due to the incentives it offers. The issue of negative gearing in residential investment in Australia is widely discussed as it relates to investment income and taxes. Several studies such as Bloxham et al. (2011), David and Soos (2015), and Grudnoff (2018) have consistently argued that most residential investors do so to utilise negative gearing and, as such, this tax incentive has been applied in property and other types of investments (Bloxham et al., 2011; PCoA, 2016).

Further, financial loss that triggers negative gearing occurs when rental income is not matched with expenses, despite the steady increase in house prices. This typifies low housing yield. The National Australia Bank (NAB) (2014) reiterated housing prices are at an all-time high relative to rents, resulting in low yield. This suggests investors would generally take financial solace from the use of negative gearing. As discussed previously, Brown et al. (2002) found that the attractiveness of negative gearing among residential investors is partly due to low yield on property. Further, Chiang et al. (2002) suggested profit margins are inversely related with capital gearing, signifying that lower yield would stimulate the deployment of negative gearing by leveraged residential investors. Moreover, the Australia Treasury Department [ATD] (2014) reported the result of a lower yield than anticipated may cause some residential investors to find themselves in a loss position that would trigger the use of negative gearing. Costello (2016) also argued that investors would normally deal with lower yield using negative gearing tax shelter benefits. Similar findings were reported by Blunden (2016). These findings highlight the role of negative gearing in residential investors’ decision making.

Premised on the financial expediency of negative gearing, there is an undisputable nexus between housing yield and the actions of residential investors. To the best of our knowledge, no study has empirically tested this relationship. This notion has also been queried by the Standing Committee on Economics of The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia as thus “The committee queried The Treasury whether investors were prepared to accept lower rental yields due to rising house prices because of the capital gains tax (CGT) discount on investment properties. The Treasury responded that this was not certain and that it was not clear that the reduced return from investment properties was any worse than other types of investment” (PCoA, 2016, p. 14). To explore this widely discussed notion, as argued by Jorgensen (1963), the study of investment behaviour can best be conducted by using an appropriate theoretical framework. Accordingly, we adopted the user cost of capital investment theory that was postulated by Dale Jorgensen in the 1960s. The underlying principles of this theory rest on investors’ choice of a cashflow path that will maximise their lifetime profit. For a leveraged residential investment, the rental income R(t) denoted the cash-inflow, while operating expenses E(t) and mortgage payment P(t) denoted the cash-outflows. Following the user cost of capital model proposed by Jorgensen (1963), with a relatively recent application by Creedy and Gemmell (2017), using an appropriate discount rate (r), the present value of the investors’ lifetime flow of profit π(t) becomes:

In a condensed form, Eq. (1) becomes:

From Eq. (2), the expression λ(t) represents the total cash outflows (which is the sum of the operating expenses and mortgage payment, i.e., {E(t) + P(t)}) of the investment. The overriding aim of the investor is to identify the combination of these cashflows that will maximise π(t). If the revenue exceeds the cost of the investment, there is an incentive to invest (Creedy & Gemmell, 2017). Since yield is the ratio of net income to capital value, an inverse relationship between housing yield and the number of investors can be explained by the expectations of investors and their profile. Some investors prioritise generating regular income from their investments, while others tend to focus on capital appreciation. If the investor is more concerned with capital growth, then negative gearing would not be an issue, suggesting that such investor would be willing to take low yield. As such, these investors would opt for a net rental loss to take advantage of negative gearing, and they would not mind a path that tends to generate a higher λ(t) relative to R(t). These important caveats of the theory will further illuminate the operationalisation of the linkage between residential investment cashflows and investment decisions. Based on this theory, coupled with the widely discussed literature on residential investment decisions, we advance the second hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2

There is an inverse relationship between housing yield and the number of residential investors.

This hypothesis suggests that lower housing yield, resulting from the combined effect of inferior rental income and rising house prices, could not be a deterrent to residential investors. Despite the benefit of negative gearing, lower yield could incentivise investors through the capital gains tax discount when they terminate their investments.

4 Data and methodology

4.1 Data sources and description

Quarterly data spanning March 1991 to June 2018 were used to empirically test the impact of negative gearing and other factors on residential investment decisions. Data on quarterly housing yield were collected from the Real Estate Institute of Australia (REIA). REIA (2020) calculated housing yield by dividing net rental income by the median house price. We use the data on second home buyers (those who purchase other residential properties apart from owner-occupier purpose), as obtained from the ABS (2018), as a proxy for the number of investors. The ABS compiled the data on the number of new loan commitments by lending purposes of each period. It explicitly outlines property lending for owner-occupier and investment purposes (ABS, 2018). This unique dataset provides insight into the number of new investor loan commitments, which can be interpreted as the investor's purchase decision on an investment property.Footnote 1 One could argue that the dataset, to a certain extent, indicates the activeness of the housing investment market in each period. As asserted by Pawson and Martin (2020), the dataset also allows us to assess how critical factors like house price appreciation and yield may impact residential investment decisions. Suppose investors' activities and the housing price appreciation rate are strongly and positively connected. In this case, it suggests that housing price appreciation is crucial in influencing investors' decisions. This would support the first hypothesis of the study, which posits a positive link between housing investors' activities and housing price appreciation. On the other hand, if no substantial evidence is available, this would indicate that investors' activities are independent of housing price appreciation.

We use house price data from Housing NSW (2021) to calculate house price appreciation. This is the natural log difference of house price which represents the quarterly capital growth of residential properties. The data on private housing supply were derived from various census reports and building approvals data from the ABS, while the mortgage lending rate for housing was collected from the Australian Prudential Regulatory Authority (APRA, 2020). The data on state final demand, which is a key measure of the economic performance of the state of NSW, were also obtained from the ABS (2020c). Finally, the estimated resident population, which refers to residents, irrespective of citizenship, nationality, or legal status, who reside in NSW, was obtained from the ABS (2020b). The literature suggests that these variables are the fundamental drivers of housing investment decisions (Belke & Keil, 2018; Hulse et al., 2012).

Since the data were gathered from diverse sources, following Lee and Lee (2014), we introduce a logarithm to eradicate possible scaling consequences on the data. The results of the correlation coefficient between the pairs of variables are presented in Table 2. The results show no perfect collinearity between any two variables of the model used in the study. Notably, the degree of association between the number of investors and yield is negative, while it is positive between the number of investors and house price appreciation. There is an apparent lack of correlation between house price appreciation and housing yield, indicating that these two variables are distinctive determinants of residential investment activities. A statistical summary of the study data is presented in Table 3.

4.2 Methodology

We deployed a structural vector autoregression (SVAR) approach to empirically examine the impact of negative gearing and other drivers of residential investment decisions. We scrutinised how the number of residential investors respond to shocks in its key determinants. The SVAR method accommodates dynamism among the variables based on economic theory and researched evidence and produces a non-recursive orthogonal error terms for impulse response analysis (Mohanty & Panda, 2020). Further, following Liao et al. (2015), a SVAR model was utilised to concurrently model multiple endogenous variables and allow for the identification of causal relationships between variables by imposing restrictions on the contemporaneous relationships between variables. By identifying these causal relationships, the SVAR model can help to distinguish between the effects of exogenous shocks and endogenous responses to changes in the variables. The use of a SVAR model can help to address the issue of endogeneity in the analysis of multiple endogenous variables, such as the housing market.Footnote 2

First, we test for the stationarity of each variable using the Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF). This is followed by the Autoregressive Dynamic Lag Bounds (ARDL Bounds) cointegration framework that was proposed by Pesaran et al. (2001). The ARDL cointegration technique can be applied regardless of the order of integration, I(0) or I(1), of the variables to allow for statistical inferences on long-run estimates (Katrakilidis & Trachanas, 2012). As such, residential investment activities can be modelled as follows:

In Eq. (3), number of residential investors (INV) are a function of shocks to housing supply (HS), population (POP), mortgage lending rate (MLR), state final demand (SFD), housing yield (HY), housing price appreciation (HPA), and to itself. This list of shocks is well documented in the literature on residential investment (Lowies et al., 2015; Newell et al., 2015; Lee, 2017; Huang et al., 2018; Gao et al., 2020; Coffey et al., 2021). Since we cannot observe the structural shocks in Eq. (3), further restrictions can be imposed to discover the fundamental structural shocks in the model. The SVAR approach will estimate the error terms for impulse response analysis.Footnote 3

Shocks to house price appreciation are expected to have a direct effect due to the rapid growth in house prices in Greater Sydney together with the benefit of capital gains tax discount (Bloxham et al., 2011; Bangura & Lee, 2022); shocks to housing yield are expected to have an indirect impact because of the advantages of negative gearing (Grudnoff, 2015, 2018); shocks to housing supply are hypothesised to have a direct impact due to its effect on price (Belke & Keil, 2018); shocks to mortgage lending rate are expected to have an indirect effects due to its impact on mortgage payment (Henneberry & Mouzakis, 2014; Alpanda & Zubairy, 2017); shocks to population are hypothesised to have a direct effect since population growth will expand the rental market and enhance dwelling investment activities (Ball, 2010; Hulse et al., 2012); and shocks to state final demand cannot be determined a priori because enhanced economic growth could increase household income which may result in a shift from renting to homeownership or it may boost dwelling investment activities if the proportion of long-term renters increases (Chu & Sing, 2004; Corder & Roberts, 2008; Saunders & Tulip, 2019).

4.2.1 Restrictions on the matrix

We make the following assumptions in our VAR estimation. First, we assume that shocks to residential investors have no impact on other variables in the system. It is assumed to be the most endogenous and responsive variable to structural shocks in the system. However, all other variables in the system have some degree of endogeneity. Population is affected by shocks to itself. Housing supply is affected by shocks to population and itself. As argued by McLaughlin (2011), Brown et al. (2008) and Yates (2008) each, housing supply often responds to shocks in population growth in Greater Sydney though sluggishly. Migration policies, the growing number of international students, family dynamics, and financially constrained low-income households seeking affordable housing are contributing factors to the growing demand for rental properties which triggers housing supply (Hulse et al., 2012). Similarly, shocks to housing supply and population will affect state final demand via its effect on the real estate industry (Bangura & Lee, 2020). Further, shocks to state final demand, housing supply, and population will affect housing price appreciation (Bangura & Lee, 2022; Duncan et al., 2018). Glaeser et al. (2005), for example, noted that the sustained house price appreciation in the USA over the past 30 years was accounted for by the supply–demand nexus and state policies. Further, endogeneity in the system is shown by shocks to state final demand, housing supply, population, and housing price appreciation on housing yield. Chinloy et al. (2014) reported that shocks to the demand for residential property investment have a greater impact on yield. Similar results were reported by Bendix (2019) in the USA, as shocks to the demand for property sub-types such as affordable housing and apartments could affect yield. Shocks to the capital growth on residentials could impact housing yield through rising rental income. Shocks to housing supply could affect yield through its effect on rental income, while shocks to state final demand could affect yield through the housing market. Mortgage lending rate is affected by shocks to the scope of economic activities, the supply and demand for housing which in turn affects housing yield and housing price appreciation. Overall, residential investment activities are affected by shocks to all the variables in the system. By putting these restrictions together, the system of equations is specified in Appendix 1.

5 Results and discussion

5.1 Unit root and ARDL bounds results

The results of the ADF unit root are presented in Table 4. House price appreciation and housing yield are stationary on level at 1% and 5% significance levels, respectively, while housing supply and residential investors are both stationary on level at 10% significant level. These variables are I(0) stationary. The remaining variables are stationary on first difference—they are I(1) variables. Overall, the mixed results of the unit root test validate the application of the ARDL bounds cointegration technique. The ARDL bounds test results are depicted in Table 5.

The results show that the variables are cointegrated as the F-statistic 8.52 is greater than the upper-bound critical values at the 1% significance level. Results here indicate the presence of a long-run relationship between the number of residential investors and its explanatory variables. This long-run dynamics in these variables are assessed using the SVAR model.

5.2 Impulse response functions

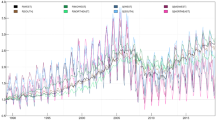

This section traces the adjustment path and the effect of structural shocks on residential investors over time. Following the information criteria as discussed earlier, we adopted one lag, the optimum lag number, for all the study models.Footnote 4 Figure 1 presents the various impulse response functions (IRF) over 60-period horizons of residential investors when there is one standard deviation shock to each of housing yield (HY), housing price appreciation (HPA), housing supply (HS), mortgage lending rate (MLR), population (POP), and state final demand (SFD).

As hypothesised, the effect of shock to housing yield on residential investors is negative for the entire 60-periods. This negative impulse response suggests that the number of residential investors increases as housing yield drops. Low yield is attributable to low net rental income and rising house prices, while higher housing yield is the result of rising net rental income relative to house prices. The latter is almost not plausible since there is evidence abound on the prolonged increase in house price in Greater Sydney (Yates, 2008; Bangura & Lee, 2019; Bangura & Lee, 2020b). This result suggests circumstances of low yield would trigger the use of negative gearing by leveraged investors, and this highlights the influence of such policy on the decisions of residential property investors. These results support the second hypothesis as residential investors may apply negative gearing to cushion any loss from their investments and benefit from the possible rate of growth in housing price over time. The electorate of Wentworth in the eastern region of Greater Sydney, for example, on average, reported the highest net rental loss of A$15,685 in Australia in the 2014–2015 financial year (Grudnoff, 2018). These tax laws combined with low interest rate continue to encourage Sydney residential investors to borrow large proportions of home loans even with low housing yield (Bloxham et al., 2011; PCoA, 2016). This has certainly answered the question of “whether investors were prepared to accept lower rental yields due to rising house prices” raised by the Standing Committee on Economics of The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia in 2016” and often by property investment analysts. Our findings supported the results of previous studies on the role of negative gearing in residential investment such as Hulse et al. (2012), Grudnoff (2015), Blunden (2016), Daley and Wood (2016), and Grudnoff (2018). These studies showed negative gearing is often used as a hook to attract property investors into the property industry.

From the results, one standard deviation shock to housing price appreciation on the number of residential investors is generally positive, highlighting the importance of capital gains in influencing residential investors. As reported by Yates (2008) and Bangura and Lee (2019), the greater demand over supply for residential properties in Greater Sydney has resulted in sustained increase in housing prices of the city. Further evidence of the continuous increase in housing price of Greater Sydney is provided by ABS (2021a) as the residential property index for this city increased from 91.1 in September 2009 to 197.9 in June 2021, representing an increase of 117.23%. The ABS (2021b) further revealed residential property continued to drive household wealth in Australia. Therefore, even with low yield, the prospect of housing price appreciation continues to drive the investment decisions of housing investors. The result supports the first hypothesis since shock to capital growth is expected to impact the number of residential investors positively. We have confirmed that the appreciation of housing price over time is critical for residential investors. These findings are consistent with Pawson and Martin (2020) and Soaita et al. (2017) as they each found capital gains to be a motivating factor for many residential investors.

As expected, shock associated with mortgage lending rate has a negative impulse response to the number of residential investors. This can be attributed to the notion that mortgage payments will increase with rising lending rates and this may discourage residential investors. However, noting the role of negative gearing, the question will be the point at which a rising mortgage lending rate will be undesirable to the investor. Similar results were also reported by Wood and Ong (2013a) and Chang et al. (2011). As hypothesised, shock to housing supply on the number of investors is largely positive over the 60-periods. Despite growing at a snail pace (Yates, 2008), the results reveal that increasing the supply of housing stock could stimulate residential property investment activities. Shocks to population have a positive reaction. Being a demand-side driver, positive shock to population is likely to boost residential investment. As noted in Schapiro et al. (2022) and Bangura and Lee (2020), an increase in the population is likely to create an instantaneous effect on housing demand which may expand the rental market and create more room for housing investment. Finally, a shock to state final demand reveals a negative reaction. Certainly, the improvement in economic activities in the state would enhance household income levels which could trigger a switch from rental to homeownership and subsequently minimise rental activities in the housing market. The recent study by Churchill et al. (2021) found evidence of transitions from rental to homeownership in Australia.

In conclusion, our study reveals residential investors can accept low housing yield, so they can utilise negative gearing while also benefiting from capital gains over time. This shows low housing yield is not a disincentive for residential investors. These findings have provided empirical evidence on the ongoing debate on whether investors would invest even at low housing yield. Our findings generally conform with the hypotheses of the study which posit an inverse relationship between housing yield and the number of investors, while a direct link is expected between capital gains and the number of residential investors. Further, we have empirically shown the negative effect of rising mortgage lending rate on residential investment as well as the direct impact of housing supply on residential investors’ decision making. However, despite the role of negative gearing in the Australian tax system, the level at which rising mortgage lending rate becomes undesirable to residential investors remains an open question.

5.3 Analysis of the magnitude of the impulse responses

The previous section discusses the impulse responses of the number of residential investors on structural shocks from the selected variables. In this section, we gauge the impact of one standard deviation shock to each of housing supply, population, mortgage lending rate, state final demand, housing yield, and housing price appreciation on the number of residential investors for the first six quarters.

The results from Appendix 3 generally reveal that the impact of shocks to mortgage lending rate, state final demand, and housing yield are greater on the number of residential investors’ than house price appreciation, population, and housing supply. The results show the negative effect of mortgage lending rate on the number of residential investors in all periods. This result is expected as the increase in mortgage lending rate would increase mortgage payment. The negative result of state final demand suggests that the boost in economic activities will likely cause a switch from rental to homeownership which tends to minimise residential investment. The negative effect of shock to housing yield on residential investment further supports the view that residential investors would continue to invest even with low yield as they can explore the benefit of negative gearing. Positive shock to population is expected to improve investment in rental properties due to its effect on rental demand. However, individual shock to housing supply and housing price appreciation exhibits less significant impact on residential investment. As reported by Bangura and Lee (2021), housing supply is not instantaneous because it is subject to zoning approvals and other regulations. As such, shock in this variable may not have immediate effect. Structural shock to house price appreciation may also not have immediate effect as investors would normally expect capital growth to be long term. Overall, the results show that shocks to mortgage lending rate, state final demand, and housing yield have immediate effect on the number of investors.

5.4 Analysis of variance decomposition

We extend the analysis by examining the proportion of forecast error variance of the variables in the system over four time periods into the future. The results are reported in Appendix 4. In the first four quarters, we found that 69–100 per cent of the variation in the number of residential investors is explained by shocks to itself. The impact of shocks to state final demand, mortgage lending rate and housing yield are more pronounced. In the case of mortgage lending rate, the results show that the variable is explained more by itself. Despite the 62–93 per cent shock to itself, population variation is also explained by state final demand, mortgage lending rate and housing yield. For state final demand, 79–86 per cent of its variation is explained by itself with some proportion by housing price appreciation and population. Almost 81–95 per cent of the variation in housing yield is explained by shock to itself with some minimal effect by mortgage lending rate and housing supply. Further, the variation in house price appreciation is largely explained by itself and state final demand. Finally, the variation in housing supply is affected by shock to itself and state final demand.

The results of the variance decomposition generally highlight mortgage lending rate, state final demand, and housing yield has immediate impact on the number of residential investors. It further highlights the exogenous nature of the number of residential investors in the system. This means policy makers should consider the state of the economy, the monetary policy domain, and the expected yield of investors in devising residential property investment policies especially in the short term.

6 Conclusion and implications

This paper examined one of the most critical questions surrounding residential investors’ decision making. So far, the existing literature has highlighted the dominance of households in residential investment in Australia, while institutional investors continue to ponder about their expansion in this asset class. Central to this discussion is the issue of negative gearing and related tax laws and how they drive investment decisions. However, previous studies on this topic are highly qualitative and they are somewhat aggregated. Departing from these approaches, we performed a quantitative analysis of how these factors would affect residential investment decisions especially at the sub-national level. We applied ARDL bounds cointegration test and SVAR framework to empirically gauge and trace the impact of the drivers of residential investors’ decision in Greater Sydney, Australia’s most populous city with strong housing investment activities. The study covered the period 1991–2018.

Numerous key findings were identified. First, we found that residential investors are willing to accept low housing yield, so they can utilise negative gearing, while also benefiting from capital gains over time. Since total return is a function of yield and capital gains, the intuition is, if return is expected to grow over time, then investors are willing to accept a low initial yield. That is, during periods of expected growth in return, we would likely see low yields and a relatively high number of investors. This explains the positive relationship between the number of residential investors and capital gains, and the inverse relationship between yield and the number of residential investors which are in conformity with the hypotheses of the study. This information revealed the investment strategy of residential investors which is characterised by their use of negative gearing to cushion any loss during periods of low yield while expecting capital growth over their holding period. Certainly, this has answered the question on “whether housing investors were prepared to accept lower rental yields due to rising house prices” raised by the Standing Committee on Economics of The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia in 2016. Second, as expected, we found a negative relationship between mortgage lending rate and the number of investors. Higher lending rate will increase cash outflows from the investment, and this could result in low yield. Generally, a negative net cash flow will trigger the use of negative gearing, while the expected growth in housing prices will drive capital value over time. This further elucidates the profile of residential investors. Finally, we found a direct relationship between housing supply and residential investors. Even though the supply of housing is almost always not catching up with its demand, we found an increase in housing stock to be a driver of residential investors. This can be attributed to the heightened interest of households in residential investment. This is also supported by the positive relationship between population and the number of residential investors.

These findings have significant policy implications. The results of the characterisation of investors could be used by tax and housing policy makers to recalibrate their tax laws relating to negative gearing especially for residential investment. This is premised on the juxtaposition of the financial solace provided to residential investors during periods of net rental loss against the ensuing rental market dynamics. Potential residential investors could also use this information for more informed decision making, especially during periods of low yields. This will help create more precision in residential investment among households. The findings about mortgage lending rate could be used by financial policy makers in the design of monetary policies to regulate the economy, particularly in circumstances where the housing market is expected to revitalise the economy. The results of housing supply could inform policy makers seeking to maintain a balance between homeownership and residential investment amid an almost perfectly inelastic housing supply. Overall, the findings have provided important tools that could inform the decisions of housing policy makers and housing investors.

Even though we have examined the role of negative gearing and other factors driving residential property investment decisions using Greater Sydney as a case study, our study has some limitations that include the level at which rising mortgage lending rate becomes undesirable to residential investors, the impact of negative gearing across property types, and the diversity of investors profile. These could be topical for future research.

Notes

This study focuses on residential investors’ activities instead of owner-occupiers. We define housing investors are those who purchase other residential properties for investment purpose instead of owner occupier. Numerous studies have employed ABS housing finance data to represent home-occupiers' purchase activities, including first-home buyers and investors (Lee and Reed, 2014; CoreLogic, 2022). Given that a purchasing activity reflects a home purchase decision, using housing finance to indicate investors' decisions or behaviour is reasonable (Brown et al., 2008; Lee, 2017). Therefore, investor decision (or behaviour) and activity are used interchangeably in this study.

Despite the use of SVAR, to ensure the robustness of our baseline results, a two stage least square model was also conducted to further address the potential endogeneity issues following Gou et al. (2020), and Wang and Lee (2022). Our results show that housing investor is positively linked with capital growth, whilst negatively associated with yield. This corroborates the baseline results that negative gearing does have a discernible impact on housing market. We did not present these results for brevity and to maintain consistency with the SVAR procedure, but they are available from the authors.

Details of this method are discussed in Appendix 1.

See Appendix 2.

References

Alpanda, S., & Zubairy, S. (2017). Addressing household indebtedness: Monetary, fiscal or macroprudential policy? European Economic Review, 92, 47–73.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) (2021a). Residential property price indexes: Eight capital cities, Available at: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/economy/price-indexes-and-inflation/residential-property-price-indexes-eight-capital-cities/latest-release

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) (2021b). Australian national accounts: Finance and wealth, Available at: https://www.abs.gov.au/media-centre/media-releases/record-house-prices-continue-drive-household-wealth

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) (2020a). Lending indicator, Available at: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/economy/finance/lending-indicators/latest-release

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) (2020b). Regional population, Available at: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/regional-population/2018-19

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) (2020c). Australia national accounts: state accounts, Available at: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/economy/national-accounts/australian-national-accounts-state-accounts/latest-release

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) (2018). Housing Finance, Australia, cat. no. 5609.0 Available at: https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/5609.0November%202018?OpenDocument

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2023). Data by region, Available at: https://dbr.abs.gov.au/region.html?lyr=ste&rgn=1

Australian Prudential Regulatory Authority (APRA) (2020). Statistical publication, Available at: https://www.apra.gov.au/statistics

Australia Treasury Department (ATD) (2014). Negative gearing, Available at: https://treasury.gov.au/review/tax-white-paper/negative-gearing

Baker, E., Bentley, R., Lester, L., & Beer, A. (2016). Housing affordability and residential mobility as drivers of locational inequality. Applied Geography, 72(65–75), 69–70.

Ball, M. (2010). The UK private rented sector as a source of affordable accommodation. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation, JFR Programme Paper: Housing Market Taskforce

Bangura, M., & Lee, C. L. (2019). The differential geography of housing affordability in Sydney: A disaggregated approach. Australian Geographer, 50(3), 295–313.

Bangura, M., & Lee, C. L. (2020). House price diffusion of housing submarkets in Greater Sydney. Housing Studies, 35(6), 1110–1141.

Bangura, M., & Lee, C. L. (2022). Housing price bubbles in Greater Sydney: evidence from a submarket analysis. Housing Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2020.1803802

Bangura, M., & Lee, C. L. (2023). Spatial connectivity and house price diffusion: The case of Greater Sydney and the regional cities and centres of New South Wales (NSW) in Australia. Habitat International, 132, 102740.

Beckett, J. (2014). Should negative gearing be abolished in preference of the UK system? The Tax Specialist, 18(1), 21–25.

Belke, A., & Keil, J. (2018). Fundamental determinants of real estate prices: A panel study of German regions. International Advances in Economic Research, 24(1), 25–45.

Bendix, A. (2019). In search of yield, more multifamily investors explore affordable housing, smaller markets, National Real Estate Investors, Atlanta, ISSN 00279994.

Berry, M. (2000). Investment in rental housing in Australia: Small landlords and institutional investors. Housing Studies, 15(3), 661–681.

Birrell, B., & Healy, E. (2013). Melbourne’s high rise apartment boom., Centre for Population and Urban Research.

Bloxham, P., Kent, C. & Robson, M. (2011). Asset prices, credit growth, monetary and other policies: An Australian case study, NBER Working Paper Series, Cambridge.

Blunden, H. (2016). Discourses around negative gearing of investment properties in Australia. Housing Studies, 31(3), 340–357.

Brown, R. M., Gregory, S., & Callum, S. (2008). Personal residential real estate investment in Australia: Investor characteristics and investment parameters.". Real Estate Economics, 36(1), 139–173.

Brown, R., Flaherty, J., & Lombardo, R. (2002). Determination of the maximum affordable price for negatively geared investments in residential property. Pacific Rim Property Research Journal, 8(4), 300–312.

Cajias, M. (2019). Understanding real estate investments through big data goggles: A granular approach on initial yields. International Journal of Housing Markets and Analysis, 12(4), 1753–8270.

Chang, K. L., Chen, N. K., & Leung, C. K. Y. (2011). Monetary policy, term structure and asset return: Comparing REIT, housing and stock. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 43, 221–257.

Chen, J., Guo, F., & Zhang, W. (2010). How important are wealth effects on China’s consumer spending? Chinese Economy, 43(2), 5–22.

Chen, N.-K., Cheng, H.-L., & Mao, C.-M. (2014). Identifying and forecasting house prices: A macroeconomic perspective. Quantitative Finance, 14(12), 2105–2120.

Chiang, Y. H., Chan, P. C. A., & Hui, C. M. E. (2002). Capital structure and profitability of the property and construction sectors in Hong Kong. Journal of Property Investment and Finance, 20(6), 434–453.

Chinloy, P., Das, P. K., & Wiley, J. A. (2014). Houses and apartments: similar assets, differential financials. The Journal of Real Estate Research, 36(4), 409–434.

Choy, L. H. T., Winky, K. O. H., & Stephen, W. K. M. (2011). Region-specific estimates of the determinants of residential investment. Journal of Urban Planning and Development, 137(1), 1–6.

Chu, Y. Q., & Sing, T. F. (2004). Inflation hedging characteristics of the Chinese real estate market. Journal of Real Estate Portfolio Management, 10, 145–154.

Churchill, S. A., Yew, S. L., & Bguyen, T. M. T. (2021). Health status and housing tenure decisions of older Australian. Real Estate Economics. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6229.12358

Coffey, C., McQuinn, K., & O’Toole, C. (2021). Rental equivalence, owner-occupied housing and inflation measurement: Micro-level evidence from Ireland. Real Estate Economics. https://doi.org/10.1111/reec.12360

Corder, M. & Roberts, N. (2008), Understanding Dwellings Investment (December 15, 2008). Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin 2008 Q4, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1318228

City of Sydney (CoS): The city at a glance. (2023). Available at: https://www.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/guides/city-at-a-glance

Cohen, J. P., & Zabel, J. (2020). Local house price diffusion. Real Estate Economics, 48(3), 710–743.

Commonwealth Bank of Australia (2023). Negative gearing and other important tax considerations for your investment property. Available at: https://www.commbank.com.au/articles/property/what-is-negative-gearing

CoreLogic. (2016). Profile of the Australian residential property investor. CoreLogic.

CoreLogic (2022). Single-family investor activity bounces back in the first quarter of 2022, CoreLogic, Sydney. Available at: https://www.corelogic.com/intelligence/single-family-investor-activity-bounces-back-in-the-first-quarter-of-2022/

Costello, G. (2016). Safe as Australian houses? financial returns, volatility and taxation policy 1999–2015, 29th Australasian Finance and Banking Conference 2016, Available from: SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2825072

Creedy, J., & Gemmell, N. (2017). Taxation and the user cost of capital. Journal of Economic Surveys, 31(1), 201–225.

Daley, J. & Wood, D. (2016). Hot property negative gearing and capital gains tax reform, Melbourne: Grattan Institute, Available from: https://grattan.edu.au/report/hot-property/

Das, P., Ziobrowski, A., & Coulson, N. E. (2015). ‘Online information search, market fundamentals and apartment real estate. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 51, 480–502.

David, L. & Soos, P. (2015). The great Australian household debt trap: why housing prices have increased, Submission to the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Economics.

Ding, C., & Knaap, G.-J. (2002). Property values in inner-city neighborhoods: The effects of homeownership, housing investment, and economic development. Housing Policy Debate, 13(4), 701–727.

Downs, D. H. (1998). The value in targeting institutional investors: Evidence from the five-or-fewer rule change. Real Estate Economics, 26(4), 613–649.

Duncan, A., Hodgson, H., Griffith, J. M., Ong, R. & Seymour, R. (2018). The income tax treatment of housing assets: An assessment of proposed reform arrangements inquiry into pathways to housing tax reform, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited Melbourne, Australia, AHURI Final Report Number 295.

Ellis, L. (2006). Housing and housing finance: The view from Australia and beyond. Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) Research Discussion Paper, Available at: https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/rdp/2006/pdf/rdp2006-12.pdf

Fischer, M. M., Huber, F., Pfarrhofer, M., & Staufer-Steinnocher, P. (2021). The dynamic impact of monetary policy on regional housing prices in the United States. Real Estate Economics, 49(4), 1039–1068.

Frayne, C., Szczypińska, A., Vašíček, B. & Stefan Zeugner, S. (2022). Housing Market Developments in the Euro Area: Focus on Housing Affordability. European Commission, Discussion Paper 171.

Fu, Y., & Qian, W. (2014). Speculators and price overreaction in the housing market. Real Estate Economics, 42, 977–1007. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6229.12071

Forlee, R. (2015). Australian residential property development for investors (1st ed.). Wrightbooks.

French, N., & Patrick, M. (2015). The plethora of yields in property investment and finance: A summary. Journal of Property Investment & Finance, 33(4), 408–414.

Gao, Z., Sockin, M., & Xiong, W. (2020). Economic consequences of housing speculation. The Review of Financial Studies, 33(11), 5248–5287.

Goetzmann, W. N., Peng, L., & Yen, J. (2012). The subprime crisis and house price appreciation. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 44, 36–66.

Glaeser, E. L., Joseph, G., & Saks, R. E. (2005). Why have housing prices gone up? American Economic Review, 95(2), 329–333.

Grudnoff, M. (2015). Top Gears: How negative gearing and the capital gains tax discount benefit drive up house prices. Canberra: Australia Institute. Available at: https://australiainstitute.org.au/report/top-gears-how-negative-gearing-and-the-capital-gains-tax-discount-benefit-drive-up-house-prices/

Grudnoff, M. (2018). Who really benefits from negative gearing? Canberra: Australia Institute. Available at: https://australiainstitute.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Who-really-benefits-from-negative-gearing_0.pdf

Guo, T., Zha, G., Lee, C. L., & Tang, Q. (2020). Does corporate green ranking reflect carbon-mitigation performance? Journal of Cleaner Production, 277, 123601.

Hayunga, D. K., Pace, R. K., & Zhu, S. (2019). Borrower risk and housing price appreciation. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 58, 544–566.

He, Y., & Xia, F. (2020). Heterogeneous traders, house prices and healthy urban housing market: A DSGE model based on behavioral economics. Habitat International, 96, 102085.

Hei-Ling, L. C., & Hui, E. C. M. (2018). How does investor sentiment predict the future real estate returns of residential property in Hong Kong? Habitat International, 75, 1–11.

Henneberry, J., & Mouzakis, F. (2014). Familiarity and the determination of yields for regional office property investments in the UK. Regional Studies, 48(3), 530–546.

Ho, H. K. (2020). Inside the world of middle-class Hong Kong transnational property investors: ‘5980 miles to my second home.’ International Journal of Housing Policy, 20(1), 75–99.

Housing NSW (2021). Housing rent and sales, Available at: https://www.facs.nsw.gov.au/resources/statistics/rent-and-sales/dashboard

Hui, E. C. M., & Wang, Z. (2014). Market sentiment in private housing market. Habitat International, 44, 375–385.

Hui, E. C. M., Zhong, J., & Yu, K. H. (2017). Property prices, housing policies for collateral and resale constraints. International Journal of Strategic Property Management, 21(2), 115–128.

Hulse, K., Burke, T., Ralston, L., & Stone, W. (2012). The Australian private rental sector: changes and challenges. Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute, AHURI Positioning Paper No. 149.

Huang, D. J., Leung, C. K. Y., & Tse, C.-Y. (2018). What Accounts for the Differences in Rent-Price Ratio and Turnover Rate? A Searchand-Matching Approach. The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 57(3), 431–475. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-017-9647-7

Jorgenson, D. W. (1963). Capital theory and investment behavior. American Economic Review, 53(2), 247–259.

Katrakilidis, C., & Trachanas, E. (2012). What drives housing price dynamics in Greece: New evidence from asymmetric ARDL cointegration. Economic Modelling, 29, 1064–1069.

Krever, R., & Sadiq, K. (2019). Non-residents and capital gains tax in Australia. Canadian Tax Journal, 67(1), 1–22.

Kohler, M., & van der Merwe, M. (2015). Long-run trend in housing price growth, Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) Bulletin, Sydney, September, 21–30

Lee, C. L. (2017). An examination of the risk-return relation in the Australian housing market. International Journal of Housing Markets and Analysis, 10(3), 431–437.

Lee, C. L., & Lee, M. L. (2014). Do European real estate stocks hedge inflation? Evidence from developed and emerging markets. International Journal of Strategic Property Management, 18(2), 178–197.

Lee, M., Lee, C. L., Ming-Long, L., & Liao, C. (2017). ‘Price linkages between Australian housing and stock markets: Wealth effect, credit effect or capital switching? International Journal of Housing Markets and Analysis, 10(2), 305–323.

Ley, D. (2017). Global China and the making of Vancouver’s residential property market. International Journal of Housing Policy, 17(1), 15–34.

Lin, Y., & C, Lee, C, L & Newell, G. (2019). The significance of residential REITs in Japan as an institutionalised property sector. Journal of Property Investment & Finance, 37(4), 363–379.

Liao, W. C., Zhao, D., Lim, L. P., & Wong, G. K. M. (2015). Foreign liquidity to real estate market: Ripple effect and housing price dynamics. Urban Studies, 52(1), 138–158.

Lowies, G. A., Hall, J. H., & Cloete, C. E. (2015). The role of market fundamentals versus market sentiment in property investment decision-making in South Africa. Journal of Real Estate Literature, 23(2), 297–314.

Martin, C. (2018). Improving housing security through tenancy law reform: alternatives to long fixed term agreements, Property Law Review, 7(184).

McLaughlin, R. B. (2011). Metropolitan growth policies and new housing supply: evidence from Australia's capital cities. Australasian Journal of Regional Studies, The, 17(1), 60–80.

Miller, N., & Sklarz, M. (2012). Integrating real estate market conditions into Home price forecasting systems. Journal of Housing Research, 21(2), 183–214.

Milligan, V., Yates, J., Wiesel, I. & Pawson, H. (2013). Financing rental housing though institutional investment – vol. 1: outcomes from investigated panel, Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute, AHURI Final Report No. 202.

Mohanty, R. K., & Panda, S. (2020). How does public debt affect the Indian Macroeconomy? A structural VAR approach. The Journal of Applied Economic Research, 14(3), 253–284.

National Australia Bank (NAB) (2014). Positive cashflow vs negative cashflow, finding the best strategy for your investment properties, Available at: https://www.nab.com.au/personal/life-moments/home-property/invest-property/gearing

Newell, G., Lee, C. L., & Kupke, V. (2015). The opportunity of residential property investment vehicles in enhancing affordable housing supply, AHURI Positioning Paper No. 166, Melbourne, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute.

NSW Department of Planning (DoP), Metropolitan Plan for Sydney 2036, December 2010.

Obereiner, D., & Bjorn-Martin, K. (2012). ‘Inflation-hedging properties of indirect real estate investments in Germany. Journal of Property Investment and Finance, 30(3), 218–240.

Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia (PCoA) (2016). Report on the inquiry into home ownership, House of Representative, Standing Committee on Economics, Canberra

Pawson, H., Milligan, V. & Yates, J. (2019). Housing policy in Australia: a case for system reform, Palgrave Macmillan US.

Pawson, H., & Martin, C. (2020). Rental property investment in disadvantaged areas: The means and motivations of Western Sydney’s new landlords. Housing Studies, 36(5), 621–643.

Pawson, H. (2018). Reframing Australia’s housing affordability problem: The politics and economics of negative gearing. Journal of Australian Political Economy, 81, 121–143.

Pesaran, M. H., Shin, Y., & Smith, R. J. (2001). Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 16(3), 289–326.

Real Estate Institute of Australia (REIA) (2020), Data REMF, Available on cost from: https://reia.asn.au/research/reia-data-remf/

Rehm, M., & Yang, Y. (2021). Betting on capital gains: Housing speculation in Auckland, New Zealand. International Journal of Housing Markets and Analysis, 14(1), 72–96. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJHMA-02-2020-0010

Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) (2015). Proportion of Investment Housing Relative to Owner-Occupied Housing, Submission to the Inquiry into Home Ownership, Available at: https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/submissions/housing-and-housing-finance/inquiry-into-home-ownership/proportion-investment-housing-relative-owner-occ-housing.html

Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) (2013), Financial Stability Review, September, Available at: https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/fsr/2013/sep/pdf/0913.pdf

Saunders, T. & Tulip, P. (2019). A model of the Australian housing market, Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA), Research Discussion Paper-RPD 2019-01.

Schapiro, R., et al. (2022). The effects of rental assistance on housing stability, quality, autonomy, and affordability. Housing Policy Debate, 32(3), 456–472.

Soaita, A. M., Beverley, A. S., Mckee, K., & Moore, T. (2017). Becoming a landlord: Strategies of property-based welfare in the private rental sector in Great Britain. Housing Studies, 32(5), 613–637.

Stapledon, N., & D,. (2012). Trends and cycles in Sydney and Melbourne house prices from 1880 to 2011. Australian Economic History Review, 52(3), 293–317.

Stone, W., Burke, T., Hulse, K. & Ralston, L. (2013). Long-term private rental in a changing Australian private rental sector. Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute, AHURI Final Report No. 209.

Tam, H. F. (2018). Behavioural response to time notches in transaction tax: Evidence from stamp duty in Hong Kong and Singapore, Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation, Working paper series WP 18/01: pp. 1–70.

Tipping, M., & Newton, R. (2015). ‘Modelling banking-hall yield for property investment. Journal of Corporate Real Estate, 17(1), 4–25.

Turk, R. A. (2015). Housing price and household debt interactions in Sweden, IMF Working Paper, No. 15/276.

Valadkhani, A., & Smyth, R. (2017). Self-exciting effects of house prices on unit prices in Australian capital cities, Urban Studies, 54, 2376–2394.

Wang, Y., Mei, B., & M, Clutter, M, L & Siry, P, S,. (2013). ‘Assessing the inflation hedging ability of timberland assets in the United States. Forest Science, 59(1), 93–104.

Wang, Z., & Hui, E. C. (2017). ‘Fundamentals and market sentiment in housing market. Housing, Theory and Society, 34(1), 57–78.

Wang, J., & Lee, C. L. (2022). The value of air quality in housing markets: A comparative study of housing sale and rental markets in China. Energy Policy, 160, 112601.

Wiesel, I., Freestone, R., & Randolph, B. (2013). ‘Owner-driven suburban renewal: Motivations, risks and strategies in ‘knockdown and rebuild’ processes in Sydney. Australia, Housing Studies, 28(5), 701–719.

Wood, G. A., & Ong, R. (2013). ‘When and why do landlords retain property investments? Urban Studies, 50(16), 3243–3261.

Wood, G., Parkinson, S., Searle, B., & Smith, S. (2013). Motivations for equity borrowing: A welfare-switching effect. Urban Studies, 50(12), 2588–2607.

Wood, G. & Ong, R. (2010). Factors shaping the decision to become a landlord and retain rental Investments, AHURI Final Report No. 142. Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute, RMIT Research Centre and Western Australia Research Centre.

Wright, D., & Yanotti, M. B. (2019). Home advantage: the preference for local residential real estate investment. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 57, 1–21.

Yates, J. (2008). Australia’s housing affordability crisis. Australian Economic Review, 41(20), 200–214.

Yang, Z., Ying, F., & Liqing, Z. (2018). A re-examination of housing price and household consumption in China: The dual role of housing consumption and housing investment. The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 56(3), 472–499.

Zhang, W., Yu, C., Dong, Z., & Zhuo, H. (2021). Ripple effect of the housing purchase restriction policy and the role of investors’ attention. Habitat International, 114, 102398.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Continuation of the SVAR methodology