Abstract

It is well-established that market governance can be provided by both public (state) and private organizations. However, the concept of private governance has been used, this article contends, to refer to two distinct forms of non-state governance: private governance and community governance. We distinguish between these two forms, arguing that private governance should be understood as the provision of market governance by (external) private parties, while community governance refers to a process where a group, a community, or society has the autonomy to govern its own affairs without interference from external authorities. The former internalizes the externalities associated with governance, while the latter comes about mainly as an unintended externality of social interaction in markets. To further illuminate the differences, and the relative strengths of these types of non-state governance, we distinguish among three elements of market governance: (1) the formation and interpretation of rules, (2) the administration of rules of ownership and exchange, and (3) the enforcement of rules. We argue that community governance is of great relevance for the formation and interpretation of the rules of ownership and exchange, which is consequently very hard to outsource to external parties, private or public. Community governance also plays a frequently overlooked role in administration and enforcement through the process of co-production. Rule formation and interpretation are theorized as the epistemic components of market governance, which can be analyzed within the Governing Knowledge Commons framework.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Markets are institutional arrangements governed by rules of property and contract. The traditional view is that these rules are a public good, to be provided by the state. This dominant view has been recently restated by Vogel in his book on Marketcraft, where he argues that “the government must create the basic infrastructure for a modern economy by enforcing the rule of law, protecting private property, and maintaining a monetary system” (Vogel, 2018, p. 1). A growing number of scholars have challenged this belief and argued that private actors can and have successfully provided market supporting institutional arrangements (Leeson, 2007b; Stringham, 2015).

The literature on private governance has identified a broad variety of institutional forms of governance, ranging from firms that develop governance frameworks, clubs that provide members with access to a governance structure, to communities that have developed rules and institutional mechanisms for the self-governance of markets. Nevertheless, the private governance literature, both at the conceptual level as well as in applied studies, has not sufficiently distinguished between private governance by organizations external to the community of market participants and self-governance by communities. We argue that private governance internalizes the externalities associated with governance, while community governance comes about mainly as an unintended externality of social interaction in markets.

The main contribution of this paper is to better identify the differences between the two types of non-state governance: private and community governance. Recognizing these differences is vital if we are to properly understand different types of market governance. If we do not take these differences into account, conducting comparative institutional analysis between the wide variety of market governance types is problematic. To facilitate this comparative work, we distinguish between three elements of market governance: (1) the formation and interpretation of rules, (2) the administration of the rules of ownership and exchange, and (3) the enforcement and adjudication of these rules. Failing to distinguish these elements makes the analysis of different configurations of market governance difficult. Granted, while most market governance is of a mixed type and pure forms of public, private, and community governance may only exist in theory, it’s still analytically important to conceptually distinguish among these three. This helps recognize different kinds of mixed governance.

The second and third elements of market governance – administration and enforcement – have received most attention in the literature which has tended to obscure the study of the first element, the formation and interpretation of rules. We contend that this oversight has led to the relative neglect of community governance, which is particularly relevant in the formation and interpretation of rules. The interpretive dimension of market governance is very hard to outsource to external private or public governance organizations because the rules, or better ‘rules in use,’ evolve and transform along with the very practices they seek to regulate. In other words, the rules, and the instruments through which these rules are interpreted, are jointly produced along with the practices they enable, constrain, and often even constitute (Cornes and Sandler, 1996; Vicary, 1997; Dekker and Kuchař, 2019).

Our analysis of community governance of markets, particularly focusing on the formation and interpretation of rules, draws on literature of community – or commons – governance (Ostrom, 1990, 2010), as well as the more recent extension to the analysis of the commons governance of knowledge (Hess and Ostrom, 2006; Frischmann et al., 2014Dekker and Kuchař, 2021a; Madison et al., 2022). Recent work has done much to theorize the relationship between patterns of interaction in focal action situations and the governance of such situations, known as adjacent action situations (Cole, Epstein, and McGinnis, 2019).

Understanding the institutional varieties of market governance, and the dynamics of community governance is relevant for at least three reasons. First, understanding the institutional variety of market governance helps us understand the relevant sequencing of (non-state) market governance, a key question in development economics (Boettke and Leeson, 2003; Murtazashvili and Murtazashvili, 2015). Second, the endogenous nature of rule formation and interpretation shapes the limits of the external imposition of designed rule systems (Boettke, Coyne, and Leeson, 2015). Third, our analysis of community governance makes clear that commons governance institutions are not merely an anachronistic form of governance but remain relevant in new markets as well as in the evolution of existing markets (Aligica and Boettke, 2009).Footnote 1

The second section reviews the debate on public and private governance of markets. The third section distinguishes private and community governance based on existing empirical studies in the private governance literature. The fourth section outlines the three distinct elements of market governance as adjacent action situations of market exchange and theorizes their interrelationships. The fifth section illustrates how the study of governing knowledge commons can enrich our understanding of community market governance, with two subsections explaining how community governance of the different elements typically functions, again drawing on existing empirical studies. The sixth and final section explores the implications of community governance as an unintended spillover (externality) of social interaction in markets and draws out the implications of the differences with private governance.

2 Public and private governance

When examining the allocation of frequencies in the radio spectrum, Coase (1959, p. 25) argued that establishing a “clear delimitation of rights on the basis of which the transfer and recombination of rights can take place through the market” is one of the central purposes of the legal system. Furthermore, due to the complexities of establishing a private legal system those operating in markets must typically rely “on the legal system of the state” (Coase, 1988, p. 10). Today, the idea that law is a public good is firmly established, with even economists who are generally skeptical of government interference tending to agree that law is, indeed, a public good.

Following Coase, Landes and Posner (1979) argued that private adjudication will underproduce the public good of good legal rules. Or, as Buchanan wrote, law “qualifies as a pure collective-consumption or public good,” because no individual “will provide, by his own restricted behavior, the benefits of law-abiding to others” (Buchanan, 1975, p. 138). Once produced, the benefits of the law can be consumed non-rivalrously, and it is impossible to exclude anyone from enjoying them. Since “law-abiding is a pure external economy, and as such involves behavior from which the actor secures no private, personal reward,” therefore, “an economic model would predict an absence of all such behavior in the strictly individualistic setting” (ibid.).

However, there is an important strand of literature which has challenged the idea that law is necessarily a public good. The private governance literature has pointed out that in many contexts the state is not a credible agent to enforce legal rules: “In the absence of government, private institutional arrangements emerge to prevent conflict and encourage cooperation” (Leeson, 2007c, p. 43). As Rajan (2004) put it, in many development settings we should assume anarchy, rather than a public authority with the ability to set and enforce rules. In other instances, public governance may be too costly to use, or the government is not willing to provide the rules, for instance in illegal markets. Private agents might, in such cases, step in to provide and enforce property rights when the government is absent or dysfunctional (Leeson and Boettke, 2009).

Stringham has systematically explored the reasons why governance might be provided privately; he directly challenged those who are convinced that law had to be provided by the government, suggesting that his “approach of private governance stands in contrast to (…) legal centralism, the idea that order in the world depends on and is attributable to government law” (Stringham, 2015, p. 5). The study of private governance in the absence of the state is considerable and has examined this type of market governance across time and space (Benson, 1989; Ellickson, 1991; Greif, 1993; Clay, 1997; Graz and Nölke, 2007).

3 Private and community governance

The study of private governance has shed light on a wide variety of institutional arrangements which have emerged in the absence of a (functional) state and have persisted as alternatives to it. This body of literature has convincingly demonstrated that legal centralism, which views law as only emanating from the state, is incomplete. However, it has not been precise about the alternative to legal centralism. Notably, we believe that the private governance literature has conflated two distinct forms of governance under the label private governance.

The first form consists of private firms or organizations that offer legal instruments to individuals or communities willing to abide by them. Although this kind of private law and governance is not centralized, it shares with the public governance what we might call legal externalism, the idea that rules are consciously created and function through mechanisms which are essentially external to market interactions, and might be imposed from the outside.Footnote 2 The second is a form of self-governance which consists of communities developing rules and institutions that allows them to govern themselves without the need to call upon external parties, whether private or public.Footnote 3

Stringham’s work on private governance provides a useful illustration of how these two quite distinct types of governance are frequently grouped together. The primary examples in his book on private governance are the private provision of law by firms such as Amazon and various credit-card companies. Stringham conceptualizes the private governance of markets as a club good, stating: “The amount of private governance in current society is far greater than people commonly recognize and governance can be analyzed as a club good that can be provided in a multitude of ways” (Stringham, 2015, p. 22). We agree that the provision of club goods by firms and other private organizations is indeed an appropriate example of private governance. However, Stringham also points out that: “the essence of law is not created by the state, but rather preexists in the conventions and understandings of the individuals that compose a given community” (2015, p. 211, our emphasis). This is the type of self-governance, which should be called community governance.Footnote 4

Leeson analyzed different kinds of self-enforcing exchanges which we believe are also better understood as examples of community governance (Leeson, 2007a, 2008a, b, 2014; Leeson and Rogers, 2012). In his analysis of “the spontaneous emergence of private institutional arrangements to solve problems between actors” (2008b, p. 184), he argued that where “the state’s eye” does not see, socially distant agents will choose to employ signaling devices to “adopt degrees of homogeneity with outsiders with whom they desire to trade” (ibid., p. 163). Using “social-distance-reducing signals to facilitate intergroup trade” (ibid., p. 176) may, according to Leeson, amount to a specific “relationship to authority, practices involving land, and religious practice and association” (ibid., p. 178). Essential to these signals is that they are costly to sustain but also that they are only visible to other community members.

As Leeson makes clear, these signals help establish membership in a community and put in place the “rules of access,” a key concept used by Ostrom to study governance of the commons. Leeson shows that these rules of access are determined and enforced by “community gatekeepers” who may, for instance, request “gifts as a sign of good faith from individuals wanting to access their communities” (ibid., p. 178). Leeson concludes that “the importance of formal enforcement in securing peaceful trade has been overstated, even when social distance between agents is significant” (p. 184). We agree. But it does not, we think, follow that “the operation of the mechanism considered here points to the spontaneous emergence of private institutional arrangements” (p. 184, emphasis added). They are indeed non-state arrangements, but to call them private is to mischaracterize this type of governance.

As examples of efficient anarchy (Leeson, 2007c), Murtazashvili and Murtazashvili present a series of case-studies on legal titling of land in Afghanistan (2015; 2016; 2019; 2020). These studies reveal a polycentric structure of community governance institutions where village leaders (maliks), village councils (shuras or jirgas), and religious arbiters (mullahs) help administer and enforce the rules of ownership. In this context, village leaders are not seen as external authorities, but rather “first among equals” (they are elected by villagers). According to Murtazashvili and Murtazashvili, these “customary forms of governance remain common across all Afghan ethnic groups” (Murtazashvili & Murtazashvili, 2015, p. 296). Despite the lack of formal titling in these systems, the subjects in their study did not express insecurity about their ownership claims. Notably, in discussing their case, the authors frequently refer to self-governance and customary governance, rather than private governance, to describe the institutional structures they encountered. Arguably, Murtazashvili and Murtazashvili recognize that the institutional arrangement in Afghanistan they describe as customary governance should be classified as community governance, not private governance, even though they present it as an instance of the latter.

The conflation of private and community governance is also apparent in Hardy and Norgaard’s (2016) study of Silk Road, the online drug market. They present their study as an extension of the private governance research framework, making the case that absent state regulation, “reputation acts as a sufficient self-enforcement mechanism” (ibid., p. 515) to allow mutually beneficial exchanges of illicit goods. The study presents the Deep Web, which hosted the Silk Road website, as an “emergent marketplace.” But here too it is not hard to find evidence that community governance is essential for the functioning, and indeed, constitution of the market. The authors argue, for instance, that the “barriers to entry into the deep web are very high” (ibid., p. 518). As such, it may be somewhat misleading to suggest, as they do, that the “Deep Web is an untaxed and unregulated marketplace [that] exists as a completely unfettered free market” (ibid., our emphasis).

The study convincingly shows that various reputation mechanisms emerged among the community of users to screen out untrustworthy participants. The authors argue that this is an instance of self-policing: “Because the users in this marketplace cannot seek legal recourse for their illegal transactions, they must police themselves” (ibid., p. 519). However, this observation underscores the importance of the user community, which has the power to refuse or revoke membership from participants unwilling to follow community rules. Reputation mechanisms and governance mechanisms like conflict resolution can indeed be offered by private parties (the authors frequently contrast Silk Road to eBay, where this is the case). Yet, the reputation-mechanism and the associated rules that Hardy and Norgaard analyze have developed largely within the online community and should therefore be regarded as a form of community governance rather than as private governance.

The importance of community governance is equally evident in Harris’s (2018) study of online pirate communities such as Pirate Bay. Following Ostrom’s classification of institutional rules – which establish boundaries, create positions, regulate the flows of information, and determine outcomes – Harris finds that “pirate communities are able to mitigate free-riding in the network” (ibid., p. 901). Yet, although Harris does frequently refer to self-governance, he still calls this governance system private. Our argument suggests not merely that community governance is a more appropriate label for this kind of governance, but rather that it is conceptually distinct from private governance. Online marketplaces and digital sharing platforms present interesting cases, precisely because private companies designing markets often compete with communities which govern themselves (Radu, 2019; see also Gradoz and Raux, 2021). These competing alternatives are both forms of non-state governance, but to lump them together as private governance masks crucial differences, differences that are significant when we seek to properly engage in comparative institutional analysis.

To reiterate, our argument does not suggest that the private governance literature overlooks community governance. Rather, it proposes that the literature insufficiently distinguishes community governance from private governance. Interestingly, the pioneers of property rights economics have clearly recognized the importance of community governance. From the outset, Alchian emphasized that property rights are often enforced communally because individuals want such enforcement and are willing to bear the associated costs. He argued: “The rights of individuals to the use of resources (i.e., property rights) in any society are to be construed as supported by the force of etiquette, social custom, ostracism, and formal legally enacted laws supported by the states’ power of violence or punishment” (Alchian, 1965, p. 817).

Similarly, Demsetz in his early work on the subject emphasized that the rules of property emerged and evolved slowly over time and were typically not deliberately designed by a public or otherwise external actor: “I do not mean to assert or to deny that the adjustments in property rights which take place need be the result of a conscious endeavor to cope with new externality problems. These adjustments have arisen in Western societies largely as a result of gradual changes in social mores and in common law precedents” (Demsetz, 1967, p. 350). Demsetz makes clear that although the main virtue of property rights is that they internalize externalities, this was often not the deliberate intention in the process of rule evolution. Instead, rule changes were typically the result of accidental or experimental ‘hit-and-miss procedures,’ in which the misses were discarded, and the hits gradually adopted more widely, for instance, through imitation. Private entrepreneurs might undertake such experiments, but discovery through trial and error also takes place within communities.

In their seminal article from 1973, Alchian and Demsetz placed communal governance front and center in their discussion of property rights, which they define as follows: “What are owned are socially recognized rights of action” (Alchian and Demsetz, 1973, p. 17). They argue that the foundation of the rules of ownership and exchange is the mutual recognition of rights within communities. This point has been recently highlighted by Wilson in a critique of purely institutional or legal conceptions of property rights (Wilson, 2020, 2023). Alchian and Demsetz make it abundantly clear that rules governing exchange and property have evolved within specific communities. They emphasize that these rules have historically been enforced within these communities and that property rights should be understood as mutually recognized rights to certain patterns of action and interaction.

4 The elements of market governance

The discussion of Alchian and Demsetz makes clear that market governance encompasses not only the emergence of rules but also the processes by which these rules are codified, made known, and understood within the community, and how the rules are enforced. We therefore propose to distinguish between three elements of market governance, which have, sometimes implicitly, been recognized in the market governance literature: the formation and interpretation of rules, the administration of ownership claims and rules, and the enforcement of rules.Footnote 5 Formation and interpretation refer to evolution and design of rules, as well as how these are understood by the actors. Administration refers to the formal or informal registration and administration of legal rules and ownership claims in, for instance, a land registry. Enforcement refers to the process by which these rules are enforced and how disputes regarding them are resolved.

The studies conducted by Murtazashvili and Murtazashvili on the titling of land in Afghanistan provide a good illustration of these three elements. The authors explain that efficient legal titling improves the security of land-tenure, in particular emphasizing “clarity of allocation, alienability, and credibility of persistence” of the titles (Murtazashvili & Murtazashvili, 2015, p. 291). In other words, they draw attention to the impact of rule administration and its consequences for efficiency. One aspect of legal titling is that it enhances “prospects for adjudication” (ibid.), providing a clearer understanding of allocation by clarifying “who actually owns land” (ibid.). To frame it in terms of the governance elements, the effective administration of rules and ownership claims can result in more predictable enforcement.

Administration of land titles is, however, a costly process. It requires surveying, documenting, and registering the land. When the information is collected it must be made accessible to the relevant communities, and in some instances, it becomes fully public. But the administration of land titles is not merely costly, it also requires the cooperation of community members who must be willing to share the knowledge they possess regarding ownership claims of land. This knowledge has been generated and subsequently shared alongside market and non-market exchanges in local communities.Footnote 6 Consequently, the different rules for use, access, and exchange of the land vary considerably between regions. The production of the relevant knowledge to govern land markets in Afghanistan does, for the most part, not happen through public or private governance, but through customary or community means.

We believe that this example of community governance is characteristic for the formation and interpretation of knowledge about the rules of ownership and exchange. Communities build on this knowledge to develop (usually costly) formal ways of registration and administration of titles, as well as the enforcement of the rules, as in fact happens in many of the Afghan communities that Murtazashvili and Murtazashvili analyze. These latter two functions – administration and enforcement – may be outsourced to private or public organizations, who could potentially provide these functions equally well or better, especially as markets scale. However, this should not overshadow the fact that the formation and interpretation of rules and ownership claims has primarily occurred through community governance, as Demsetz noted in his observations on the evolution of social customs and common law. The resulting knowledge often forms the basis of attempts to administer and formalize rules, contracts, and ownership titles.

The case-studies of land titling in Afghanistan also illustrate that in many practical instances we encounter mixed forms of governance. In other words, community governance is often entangled with private and/or public governance, especially when markets extend beyond a particular community. We might, for instance, observe that while the formation and interpretation of rules are done through community governance, administration and enforcement are (partly) outsourced to private organizations or public authorities. Distinguishing between the different elements of market governance thus helps us to disentangle the often-messy realities of the various mixed forms.

To further conceptualize the relationship between the arena of private exchanges, the market, and the governance of markets it is useful to draw on the framework for institutional analysis as developed at the Ostrom Workshop (McGinnis, 2011a; Dekker & Kuchař, 2021b). In this framework the focus is on a particular action situation – in this case market exchange. This situation is analyzed in the context of a set of rules, a community of actors, and certain resource characteristics. In more recent work, the idea of “adjacent” action situations has been introduced (McGinnis, 2011b; Cole et al., 2019).Footnote 7 This concept is of great relevance if we want to think of the way that the focal situation, market exchange, is related to market governance.

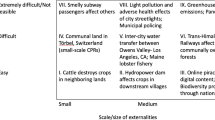

We consider each of the different elements of market governance, as outlined above, to constitute action situations adjacent to market exchange. In this we build on Cole (2017) who suggested that “the various processes by which formal rules are transformed into working rules are themselves action situations, including law enforcement and other action situations in which legal rules are evaluated and interpreted” (Cole, 2017, p. 843). In Fig. 1 we specify the relationship between market exchanges and the different elements in terms of governance, co-production, and joint production.

The configurations of governance we find in different markets will depend on the relative costs of the different types of governance. In theory, all three elements of market governance may be provided through ideal-typical community (or commons) governance. This would mean that all the adjacent action situations would be populated by the same actors that we find in the focal action situation. In non-ideal empirical settings, we are more likely to encounter a diversity of configurations of these elements. Most communities will not conform to an ideal-typical model of equal rights for all members. Instead, they will recognize different kinds of positions, leading to stratified rules of access and membership, with some members having more of a say over certain governance situations. External private or public actors may also control the different governance functions. There are good reasons to think that the administration and enforcement elements of governance are relatively easier to outsource to private and/or public organizations. In such cases there will be external actors (non-market participants) in the adjacent governance situations with specific rights to administer or enforce rules governing actions and interactions in markets.

5 Community governance as governance of knowledge commons

In the previous section, we mentioned the framework for institutional analysis (IAD) developed by Elinor Ostrom and her collaborators (Ostrom, 2005). This framework was first introduced to study the governance of commons in the natural environment (Ostrom, 1990) and was later modified for the study of knowledge commons (Frischmann, Madison, and Strandburg, 2014). The Governing Knowledge Commons (GKC) framework draws on conceptual tools of the IAD framework. It emphasizes the importance of rules in structuring interactions related to different kinds of knowledge-based resources. These include position rules (the different roles actors may occupy), boundary rules (how one enters or leaves certain positions), choice rules (about which actions are permissible given certain positions), and scope rules (defining the range of possible outcomes based on the use of the knowledge). This type of structure was also used in Harris (2018). In the context of knowledge commons, Hess and Ostrom additionally talk of the rights to contribute to the knowledge-based resource, and extract, or remove information from it (Hess and Ostrom, 2006).

In the GKC framework, “commons” refers to: “a form of community management or governance. It applies to resources and involves a group or community of people, but it does not denote the resources, the community, a place, or a thing. Commons is the institutional arrangement of these elements” (Strandburg, Frischmann, and Madison, 2017, p. 10). The term commons is thus akin to community governance discussed above. Importantly, what distinguishes commons from other kinds of governance (such as private or public governance) “is institutionalized sharing of resources [knowledge] among members of a community” (Frischmann, Madison, and Strandburg, 2014, p. 2). This implies that for knowledge governance to qualify as a knowledge commons, individual members should possess the rights to extract from it, contribute to it, or alter it.

Membership rules will structure the degree to which different types of members have such rights. If these rights are absent, we cannot speak of community governance. An example of private knowledge governance would be an organization that provides access to specific knowledge infrastructures like an encyclopedia or a repository. An instance of knowledge governance as a knowledge commons is exemplified by the community-governed structure of Wikipedia.Footnote 8 The GKC literature provides both empirical studies which demonstrate the type of knowledge relevant for the governance of markets and conceptual tools to better understand market governance and the production of rules (Dekker & Kuchař, 2021a; Murtazashvili et al., 2022; Madison et al., 2022).

The Governing Knowledge Commons (GKC) framework provides a lens for researching the governance of knowledge, including formal, informal rules, and norms which are an essential part of market governance. Frischmann (2012) and Hadfield (2016) have conceptualized these shared rules as the elements of legal infrastructures on which markets rely. The shared knowledge about these rules, as well as their practical usage, is often intricately linked to the private exchanges within markets, the work of judges, public administrators, bureaucrats, legislators, and notaries.

This formation and interpretation of knowledge is intimately tied up with the practices in the focal action situation, market exchanges. Shared understandings of relevant categories and how rules are used and interpreted in practice are closely entangled with the practices, and knowledge about them will, consequently, be very costly to acquire by outside parties (Hayek, 1945). Rules and ownership claims may be stored and codified in such forms as written documents, standards, laws, or regulations (Boudreaux and Aligica, 2007). But beyond that, the shared knowledge on which market participants rely is often tacit, inarticulate, and uncodified (Lavoie, 1986). This shared knowledge is produced by the members of relevant communities through market and non-market exchanges as well as through dispute resolution.

We propose to analyze this kind of community governance of rules and other institutional elements by incorporating the configuration of adjacent action situations into the GKC framework. In doing so we rely on two concepts which have been used in community governance research: co-production (Alford, 2014) and joint production (Cornes and Sandler, 1996). In the following subsections, we argue that the administration and enforcement of rules tends to rely on market participants’ co-production, and that the formation and interpretation of rules mainly occur as an unintended by-product of private exchanges, through joint production.

5.1 Co-production of the administration and enforcement of rules

As we argued above, we believe that the administration and enforcement elements of market governance can be provided through various communal, private, or public governance structures. Such structures must, nonetheless, rely on co-production by the community of participants. The basic way of thinking about co-production of such governance function is well illustrated by the studies of goods and services such as policing, later expanded to education and healthcare, which demonstrated that the effective production of these goods requires co-production (McGinnis, 1999). Co-production takes place when actors who do not belong to the same organization provide complementary resources that contribute to the production of the relevant good or service (Davis & Ostrom, 1991). Co-production thus refers to the process by which users of a good or service provide crucial inputs to complete the production of the good (Ostrom, 1996). This implies, as Rayamajhee and Paniagua point out, that in cases when “inputs are contingent upon preferences and external constraints that are intractable to outsiders,” co-production “requires active engagement of insiders” (2021, p. 78). When applied to governance this means that without the knowledge shared by insiders, external parties cannot govern effectively.

The administration of property titles, such as land ownership for instance, requires a willingness by market participants to register their claims with the (typically public) authorities. If such willingness is not present, then the public registry will soon grow outdated and useless. The same is true for the reputation systems frequently used in both private and communally governed online marketplaces, such as for instance the one studied by Hardy and Norgaard (2016). Co-production is typically costly for the users involved and the governance structures thus must be organized such that individuals have reasons to incur those costs, and more generally they must be willing to accept the (partly) external forms of governance.

That a centralized administration does not always help define, register, and enforce property rights is evident when we return to the case of Afghanistan where, as far as land governance is concerned, the government remains untrustworthy to the extent that “few even want legal titles” to their property (Murtazashvili & Murtazashvili, 2020, p. 365). Whether state governments can successfully provide property rights depends, among other things, on the administrative and adjudicative capacity of the state bureaucracy, as well as on the costs of resolving land disputes, accountability mechanisms, and political legitimacy (Murtazashvili & Murtazashvili, 2016, p. 110).

The findings in Afghanistan are corroborated by recent research in Malawi, a country in Southeastern Africa with a population close to twenty million, where “unwritten customary property rights are the most common form of land tenure in the country. Most smallholder farmers live on customary land, which covers an estimated 69% of the territory” (Ferree et al., 2022, p. 5). On customary land, the governance of land ownership is embedded in community practices. Through surveying a sample of the Malawi population, Ferree et al. designed an experiment to analyze how ownership claims over land and securing these claims was understood by citizens, with a focus on the legibility, in our terms the administration, of these claims.

Similar to the situation in Afghanistan, people in Malawi also recognize the significance of having clearly defined and enforceable property rights to land. The legibility of property titles through public administration may, however, become a double edge sword in situations where the government can arbitrarily use these property claims to the detriment of claim holders or in cases where access to effective public enforcement mechanism is too costly (Leeson & Harris, 2018). For this reason, landowners in Malawi frequently make their property titles legible without recourse to state authority.

The authors, following Scott (1998), find that legibility is a strategic resource for citizens. An ownership claim made within a community has a public component to it, through something as basic as a registration in a headman’s notebook, but this knowledge is frequently concealed from public authorities, who are likely to abuse it through predation. In this context, governing the knowledge as commons – where certain actors are denied access, while others are granted positions that allow access and contributions to this shared knowledge – serves as a means to protect property rights within the community. Simultaneously, it enables market exchanges among members.

The enforcement of rules and the adjudication of conflicts are similar in this respect. Enforcement begins with the interaction between two contracting parties, where both have clear incentives to ensure that the other fulfills its obligations. It is further provided by fellow market participants who might seek to help enforce contracts and who share knowledge about the reputation of other trading partners, as Alchian and Demsetz already recognized. Seeking formal adjudication is typically the last resort when community governance has proven inadequate. But it will only occur when there is trust that the external governance party will not abuse its power or the knowledge which will have to be disclosed during the search for an effective adjudication procedure. It thus seems clear that both the administration and enforcement of the rules of ownership and contract are co-produced by communities, even when private or public governance is present. However, if this were the full extent of the relevance of community governance, it would perhaps not be necessary to distinguish it as a separate type. But, as we suggest below, community governance is also essential for the formation and interpretation of rules of ownership and exchange.

5.2 The joint production of market rules

In our discussion of the pioneering work by Alchian and Demsetz, we saw that they believed that property rights and rules of contract had evolved gradually within communities and depended on the social and mutual recognition of these rights. If markets indeed rely on the mutual recognition of ownership claims and shared underlying ideas about which artefacts can be traded, then we should study how this knowledge emerges and evolves. This is the first element of market governance, the formation and interpretation of rules. We believe that market rules come about as an unintended consequence of repeated interactions, through a process of joint production (Cornes and Sandler, 1996; Vicary, 1997; Dekker and Kuchař, 2019; Romero and Storr, 2023). Joint production of knowledge refers to the creation of knowledge as an (often unintended) by-product or spillover from social practices, such as the exchange of goods.

This idea is not entirely novel. Economists of the Austrian school, most prominently Menger and Hayek, have long argued that market-supporting institutions, such as money, have evolved alongside markets. Hayek has argued that rules emerge from the spontaneous interaction of many different individuals, often as a result of human action but not of human design (Hayek, 2014; Menger, 2009). Hayek frequently spoke of law, language, and money as the three orders which have evolved through use (Dekker, 2016). However, Hayek does not talk of a market with organizations offering competing sets of designed rules, as some of the literature on private governance does. Instead, he argues that the rules of property and contract have emerged over time through repeated interactions in a process which is largely endogenous to market interactions themselves. This need not be a process with uniform outcomes, instead the differences between the rules of separate groups are likely to reflect differences in external circumstances as well as cultural differences.

Berman made a similar point regarding the evolution of law as an essential resource for economic development. He argued that this evolution is not solely a result of legal design or mere material interests, but rather, that the two have evolved in tandem:

Law is as much a part of the mode of production of a society as farmland or machinery; the farmland or machinery is nothing unless it operates, and law is an integral part of its operation. Crops are not sown and harvested without duties and rights of work and of exchange. (Berman, 2013, p. 557)

In this evolutionary account of the rule development, the co-evolution of practices and rules becomes central. In this co-evolutionary process, the rules of property and exchange, along with their interpretations, are jointly produced through the corresponding practices that are enabled (and often even constituted) by these rules. This is why it is important to consider market exchanges and the different elements of market governance as adjacent action situations.

This could potentially lead to the ossification of both rules and patterns of interaction, but typically, the use of rules transforms them at the margin, because “people continuously draw on social structure in acting, with their behavior leading either to the reproduction or transformation of those structures” (Lewis & Runde, 2007, p. 179). The idea of rules as knowledge resources which enable social interactions also becomes apparent when we recognize that existing patterns of interaction enable related patterns of interaction, for instance through analogy (Dekker & Kuchař, 2016).

In the context of market governance, joint production implies that the rules of ownership and exchange are produced and reproduced alongside the very exchanges they regulate. Thus, market supporting rules emerge endogenously: they are produced, reproduced, and transformed through repeated interactions, and they crucially rely on evolving abstract categories that are used by the participating actors and, more broadly, within the community (Hayek, 2014; Wilson, 2020). It is important to emphasize that our account of the evolution of shared understandings of property and the associated rights and duties is not meant to be static or harmonious. Cultures are dynamic and frequently contain internal tensions or contradictions (Storr, 2013). Rules can evolve to facilitate commodification of particular artefacts and enable private market exchanges (Kuchař, 2016), but the opposite can also be the case. To illustrate this point, let us look at a case in which property is redefined to make it incompatible with market exchanges.

Over the past decade, disputes in water management that have led to a remarkable institutional innovation through which rivers in Ecuador, Colombia, India, Australia, and New Zealand have been given the status of legal personhood, and consequently, obtained certain legal rights. This is a result of a search for institutions that would allow communities to effectively manage their environmental resources (Garrick et al., 2012). To illustrate, we focus on the Whanganui River Claims Settlement Act from 2017, which declared that “a legal entity is created and clear de jure rights are defined and granted to the river and its catchment” (Part 2, Sect. 14).

As a result of this Settlement Act, the Whanganui – the third-longest river of New Zealand – came under the care of two guardians: an indigenous community and officials representing the government of New Zealand. They share the “authority to make decisions around management, exclusion, and alienation in the future, as well as to make decisions over matters of access and withdrawal” (Talbot-Jones & Bennett, 2019, p. 3). The act created a legal entity through which the river acquired legal standing (it has a right to sue and be sued in court), on whose behalf guardians can enter and enforce contracts, and which has the right to own property. The act aimed to reflect indigenous Māori customs and values, rather than to continue to impose an alien legal framework upon the community and the river. The assignment of the legal personhood to the Whanganui River is not a result of modern ecological thought, but an attempt to do justice to the Māori relational view of the river as an equal partner in a reciprocal relationship. The Māori consider the river as an ancestor, to which they have duties:

According to a whakapapa framework, relationships are normatively laden and obligations form part of our relationships. Speaking about the river’s duties towards human beings presupposes a historical perspective. The Māori are born into a network of relationships, and the river forms part of these relationships. Growing up next to the river and making use of it – benefiting from it – means that the river fulfils its duty within this network. Speaking of a duty with regard to the river is therefore not prescriptive for the future, but rather acknowledges that the river has fulfilled its duty in the past. (Kramm, 2020, p. 312)

This Māori perspective is a good example of an evolved understanding of the river, which has developed through repeated interactions within (and across) relevant communities. This understanding is clearly at odds with certain Western interpretations of what a river is and what the associated institutional rules are (regarding positions, choices, access). It does not consider the river as a common pool resource from which people can extract, nor as a natural resource which can be owned, bought, and sold by other legal persons.

The public-legal recognition of the river as a legal person is a combination of two distinct types of knowledge: the legal system of New Zealand, and the Māori knowledge about the river. The Settlement Act signifies a transformation of both these systems of knowledge, but it nonetheless builds on existing understandings: the notion of legal personhood (also, for instance, awarded to business corporations), and the Māori’s view of the river as an ancestor. This construction of a shared understanding of the river makes clear that the ability to privately appropriate or sell an artefact, such as a natural resource, depends on agreement regarding how that artefact is to be categorized. How we see a river, a piece of land, or a person, and how we understand the relationships among these, determines what rules apply, what rights will be authorized and enforced, and who is responsible for the monitoring and conflict resolution. Hence, it is not sufficient to take the formal or legal rules as brute facts that cause certain outcomes (Ostrom, 1986; Bryan, 2000). Rather, the way these rules are understood, interpreted, and applied is key.

Conflicts may arise when such categories and rules are not shared, making adjudication and conflict resolution crucial in the formation of shared categories, rules, and the associated interpretations. A similar process might unfold when administration of rules and ownership claims is outsourced, as certain shared understandings, which were previously left implicit, must now be made explicit. In this sense, the three elements of market governance are not wholly separate; the latter two – administration and enforcement – rely on the underlying epistemic dimension of the formation and interpretation of rules.

In examining the proper functioning and constitution of market exchanges, “just being able to formulate rules will not be enough” because rules and their interpretation exists in the practice guided by these (Taylor, 1995, p. 177).Footnote 9 Practice embodies the continuous interpretation and reinterpretation of the rule. If it indeed holds true that rules come about through joint production and are intimately linked with the practice itself, it seems unlikely that an external private or public party could take over this function.

At least theoretically an entrepreneur should be able to appropriate the collectively generated knowledge (a modified rule) to supply a new variant of market governance. However, it seems unlikely that non-participants in this market can appropriate this knowledge, for a variety of reasons. As we argued above, practices and rules are intimately related. This point is reinforced by Cole, who argues that legal property rights that authorize actors to access, use, or sell a resource or an asset are often not identical to the ‘rules-in-use’ (Cole, 2017). Understanding these rules requires active engagement, a notion that aligns well with the concept of tacit knowledge.Footnote 10 External parties are unlikely to have access to this knowledge, or the ability to modify it substantially.

6 Markets, externalities, and market governance

In the traditional view of market governance, as for instance expressed by Buchanan, law is considered a public good, and law abiding is seen as a pure externality. The private governance literature has convincingly shown that the externality can be internalized by organizations or entrepreneurs who provide private governance to facilitate various markets. The community governance alternative differs from both private and public governance because it suggests that elements of market governance are produced through positive spillovers from market and non-market exchanges. These positive externalities lead to rule formation and interpretation and form the basis of administration and enforcement mechanisms. Therefore, distinguishing between private governance and community governance as two distinct forms of non-state governance is not just a matter of semantics. These two types of governance are conceptually distinct, empirically identifiable, and carry different implications for how we conceptualize market governance and think about the institutional development of markets.

To start with the latter, the development of markets, it helps to return once more to the case of legal titling in Afghanistan. One of the key questions Murtazashvili and Murtazashvili ask is what the proper sequencing for legal titling is, and at what point is it worth the investment. They outline the types of costs involved, including surveying, adjudicative capacity, enforcement capacity, and ensuring the state’s credibility regarding property rights. However, their argument about customary governance makes clear how much of the investments into rules, conflict resolution, and adjudication have already been borne by communities. Their capacity for customary governance has emerged gradually alongside local practices. Without these earlier developments, the cost for public or private actors to invest in a market governance system would be prohibitive. But precisely because jointly produced elements of governance have given rise to the formation of shared rules, markets will have already emerged and developed. Private or public actors who come in later to provide external forms of governance can do so because they can build on these previous investments. This holds true at least when they are present, which might not be the case in various cases involving transitions from radically different economic systems.

This, perhaps paradoxically, suggests that markets, as institutionalized arrangements of ownership and exchange, exist because of (not despite) certain kinds of externalities. These externalities are the spillover effects of market and non-market exchanges, through which shared cognitive categories that underpin the rules of property and contract develop. It is important to recognize that it is not a singular, large-scale externality that creates a full set of rules about ownership and exchange all at once. Rather, these externalities are small steps in an evolutionary process. As such, changes in community governance are incremental, and the external effects of each step are typically too small for individuals to attempt to capture them. This insight provides a more nuanced argument for the importance of endogenous rules in development settings (Boettke, Coyne, and Leeson, 2015). The sustained relevance of community governance in the form of co-production also reinforces the idea that to maintain legitimacy, external governance by private or public organizations must be compatible with local rules and the shared knowledge that underpins them. Recognizing the importance of these spillovers also suggests, as even Vogel (2018, p. 145) – who generally favors a significant degree of public ordering of markets – admits, that to allow endogenous rule formation to occur, the best thing that governments (and we may add external private organizations) can do in certain situations is get out of the way.

The notion of adjacent action situations suggests that the spillovers in terms of rule formation and interpretation are limited in scope. These are not global externalities available at no cost to everyone, but rather localized externalities that are produced within, and have effects on, a specific community of actors and potentially in closely related communities. Consequently, knowledge is not a public pool accessible to all; it is a resource intricately tied to specific practices and broader contexts of understanding.Footnote 11

One could further push the question of where markets come from and ask why market-enabling rules sometimes emerge, and at other times do not. That question, however, lies beyond the scope of our paper here. Nonetheless, the idea of rule formation through positive spillovers highlights another difference between private and community governance. In some of the private governance literature, including the conceptualization put forward by Stringham, there is an idea that governance can be provided competitively. This can be understood as the notion that private organizations compete with public providers in the supply of governance, or that different private organizations compete among each other. In cases where community governance prevails, and rules are endogenous, the competition occurs instead between communities bearing different sets of rules. In this case our attention should be on community formation (focusing on rules of access and exclusion) and community growth, as suggested by Geloso and Rouanet (2023), rather than competition among various governance providers.

7 Conclusion

In this paper, we have drawn a distinction between community governance and its private and public counterparts. We argued that the literature on private governance has grouped together two quite distinct forms of non-state governance: governance provided by private organizations, and the other emerging from the collective efforts of the community of market participants themselves. These forms of governance are ideal types, but their analytical differences are crucial in dissecting the diverse array of institutional governance configurations observed around the world. We have claimed that private governance often succeeds in internalizing the externalities, thereby privately providing certain public goods. Community governance, on the other hand, comes about through the joint production of governance elements by way of spillovers from market and non-market exchanges. The enduring relevance of community governance in development settings, as well as in emerging digital markets, strengthens the case that market governance can often be provided by non-state actors.

The differences between private and community governance are relevant for a comparative institutional analysis between different forms of market governance. We have suggested that this comparative institutional analysis would be improved if the different elements of market governance – namely (1) the formation and interpretation of rules, (2) administration of the rules of ownership and exchange, and (3) the enforcement of rules and conflict adjudication – were distinguished from each other. Our conceptual discussion of community governance, together with a reexamination of some important studies in the existing private governance literature, suggests that outsourcing the governance of the formation and interpretation of rules to external parties may prove very difficult. Community governance is also likely to remain an important part of the second and third elements through co-production of the knowledge necessary for effective administration, enforcement, and adjudication.

Our approach opens important questions about the diversity of non-state governance and their respective institutional forms. In terms of community governance, we should further explore how the rights to contribute to, extract from, and alter the shared knowledge within communities is distributed. This should include an analysis of why such distributions come about, and an evaluation of their relative efficiency. On the private governance side, our argument raises questions about the circumstances under which organizations will rely on co-production or even more community inputs. Further analysis is likely to refine the externalism/internalism distinction we have relied upon here, revealing an even broader spectrum of non-state governance forms.

The key takeaway from our analysis is that the rules of ownership and exchange, the very scaffolding that enables markets to function, are deeply rooted in community governance. This type of governance is often viewed as a traditional, customary, or premodern. Yet, as Elinor Ostrom pointed out, “commons governance institutions are by no means relics of the past” (Ostrom in Aligica and Boettke, 2009, p. 151). Aligica further reinforces this notion, stating: “Modern economic and governance performance depend on that underlying and neglected social dimension that acts as a necessary condition for their functioning” (Aligica, 2018, p. 193). In the context of development, community governance is not merely a foundational base for market governance; it also serves as the driving force through which rules emerge and adapt in new and unique markets, such as digital markets or in the ever-evolving Web3 communities. As markets continue to transform, the joint production and interpretation of ownership and exchange rules will persistently shape the landscape of market governance. We would do well to pay close attention to it.

Change history

28 November 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-023-01117-1

Notes

Elinor Ostrom was clear on this point: “To those who doubt the viability of commons governance institutions in the modern age, let me point out that many such institutions exist and are proliferating, and not only in the area of natural resources management. … [the] modern corporation is itself a case in point … a contemporary housing condominium is also a commons institution … urban neighborhoods … the Internet is another commons that is certainly relevant to modern life.” (Ostrom in Aligica and Boettke, 2009, p. 150).

To put it differently, this view conceives of private governance as an example of private actors offering the type of governance structures typically offered by the state. This was the kind of privatization Elinor Ostrom was critical of. For a discussion see Araral (2014).

A similar grouping together of different institutional forms is present in the private provision of public goods literature, which sometimes imagines this private provision as small contributions by many different individuals to a public good (Bergstrom, Blume, and Varian, 1986) and at other times as private firms selling previously public goods or bundling them with private goods (Fraser, 1996).

For a critical discussion of ‘club contractarianism,’ see Brennan and Kliemt (2022).

The essays collected in Brousseau and Glachant (2014) provide an excellent point of departure to map the various aspects of market governance.

Reliance on this shared knowledge was even more relevant since a cadastral survey had not been undertaken in Afghanistan since the late 1970s, when the survey was not even completed.

McGinnis suggested that one action situation is adjacent to another if the outcome of the former “influences the value of one or more of the working components” of the latter (2011, p. 53).

The difference between private governance and community governance is not a sharp line, but instead a continuum. The greater the extent to which the rights to extract, contribute, and alter are held by members the closer we are to an ideal-typical form of community governance. The greater the extent to which these rights are held by a private organization, the closer we are to an ideal-typical form of private governance. One referee suggested, rightly, that community governance relies more on ‘voice,’ while private governance relies more on ‘exit’.

Taylor made the case that “real practical wisdom is less marked by the ability to formulate rules than by knowing how to act in each particular situation. There is a crucial ‘phronetic gap’ between the formula [rule] and its enactment” (Taylor, 1995, p. 177).

This point in reinforced by Kealey and Ricketts (2021) who argue in their analysis of (scientific) knowledge commons, that knowledge typically requires active engagement and is thus not nearly as non-excludable as is typically believed.

In markets the community of actors will not always be local but can be a geographically dispersed industry (Vachris and Vachris, 2021).

References

Alchian, A. A. (1965). Some economics of property rights. Il Politico, 30(4), 816–829.

Alchian, A. A., & Harold, Demsetz. (1973). The property rights paradigm. The Journal of Economic History, 33(1), 16–27.

Alford, J. (2014). The multiple facets of co-production: Building on the work of Elinor Ostrom. Public Management Review, 16(3), 299–316.

Aligica, P. D. (2018). Public entrepreneurship, citizenship, and self-governance. Cambridge University Press.

Aligica, P. D., & Peter, J. B. (2009). Challenging institutional analysis and development: The Bloomington School. Routledge.

Araral, E. (2014). Ostrom, Hardin and the commons: A critical appreciation and a revisionist view. Environmental Science & Policy, 36(February), 11–23.

Benson, B. L. (1989). Enforcement of private property rights in primitive societies: Law without government. Journal of Libertarian Studies, 9(1), 1–26.

Bergstrom, T., Blume, L., & Varian, H. (1986). On the private provision of public goods. Journal of Public Economics, 29(1), 25–49.

Berman, H. J. (2013). Law and language: Effective symbols of community. Edited by John R. Witte. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Boettke, P. J., & Peter, T. L. (2003). Is the transition to the market too important to be left to the market? Economic Affairs, 23(1), 33–39.

Boettke, P. J., Coyne, C. J., Peter, T., & Leeson (2015). Institutional stickiness and the new development economics. In Culture and economic action, edited by Laura E. Grube and Virgil H. Storr, Edward Elgar Publishing. 123–46.

Boudreaux, K., & Paul Dragos Aligica. (2007). Paths to property: Approaches to institutional change in international development. Hobart Papers 162. Institute of Economics Affairs.

Brennan, G., & Kliemt, H. (2022). Politics as exchange? Homo Oeconomicus.

Brousseau, E., & Glachant, J. M. (2014). The manufacturing of markets: Legal, political and economic dynamics. Cambridge University Press.

Bryan, B. (2000). Property as ontology: On Aboriginal and English understandings of ownership. Canadian Journal of Law & Jurisprudence, 13(1), 3–31.

Buchanan, J. M. (1975). The Limits of Liberty: Between Anarchy and Leviathan. University of Chicago Press.

Clay, K. (1997). Trade without law: Private-order institutions in Mexican California. The Journal of Law Economics and Organization, 13(1), 202–231.

Coase, R. H. (1988). The firm, the market and the law. University of Chicago Press.

Cole, D. H. (2017). Laws, norms, and the institutional analysis and development framework. Journal of Institutional Economics, 13(4), 829–847.

Cole, D. H., Epstein, G., & McGinnis, M. (2019). The utility of combining the IAD and SES frameworks. International Journal of the Commons 13(1).

Cornes, R., & Todd Sandler. (1996). The Theory of Externalities, Public Goods, and Club Goods. Cambridge University Press.

Davis, G., & Ostrom, E. (1991). A public economy approach to education: Choice and co-production. International Political Science Review, 12(4), 313–335.

Dekker, E. (2016). The Viennese students of civilization: The meaning and context of Austrian economics reconsidered. Cambridge University Press.

Dekker, E., & Kuchař, P. (2016). Exemplary goods: The product as economic variable. Schmollers Jahrbuch, 136, 237–255.

Dekker, E., & Kuchař, P. (2019). Lachmann and Shackle: On the joint production of interpretation Instruments. Research in the History and Methodology of Economic Thought, 37B, 25–42.

Dekker, E., & Kuchař, P. (2021a). Governing markets as knowledge commons. Cambridge University Press.

Dekker, E., & Kuchař, P. (2021b). The Ostrom workshop: artisanship and knowledge commons. Revue d’Économie Politique, 131(4), 637–664.

Demsetz, H. (1967). Toward a theory of property rights. The American Economic Review, 57(2), 347–359.

Ellickson, R. C. (1991). Order without law: How neighbors settle disputes. Harvard University Press.

Ferree, K. E., Honig, L., Lust, E., & Phillips, M. L. (2022). Land and legibility: When do citizens expect secure property rights in weak states? American Political Science Review, 1–17.

Fraser, C. D. (1996). On the Provision of Excludable Public Goods. Journal of Public Economics, 60(1), 111–130.

Frischmann, B. M. (2012). Infrastructure: The social value of shared resources. Oxford University Press.

Frischmann, B. M., Madison, M. J., & Strandburg, K. J. (2014). Governing knowledge commons. Oxford University Press.

Garrick, D., Bark, R., Connor, J., & Banerjee, O. (2012). Environmental water governance in federal rivers: Opportunities and limits for subsidiarity in Australia’s Murray–Darling river. Water Policy, 14(6), 915–936.

Geloso, V., & Rouanet, L. (2023). Ethnogenesis and Statelessness. European Journal of Law and Economics.

Gradoz, J., Raphaël, & Raux (2021). Trolling in the deep: Managing transgressive content on online platforms as commons. In Governing markets as knowledge commons, edited by Erwin Dekker and Pavel Kuchař, Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. 217–37.

Graz, J. C., Andreas, & Nölke (2007). Transnational private governance and its limits. Routledge.

Greif, A. (1993). Contract enforceability and Economic Institutions in early trade: The Maghribi traders’ coalition. The American Economic Review, 525–548.

Hadfield, G. K. (2016). Rules for a flat world: Why humans invented law and how to reinvent it for a complex global economy. Oxford University Press.

Hardy, R. A., & Julia, R. N. (2016). Reputation in the internet black market: An empirical and theoretical analysis of the deep web. Journal of Institutional Economics, 12(3), 515–539.

Hayek, F. A. (1945). The use of knowledge in society. The American Economic Review, 35(4), 519–530.

Hayek, F. A. (2014). The results of human action but not of human design. In The market and other orders, edited by Bruce Caldwell, 293–303. The Collected Works of F.A. Hayek Volume XV. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hess, C., & Elinor Ostrom. (2006). Understanding knowledge as a commons from theory to practice. MIT Press.

Kealey, T., & Ricketts, M. (2021). The contribution good as the foundation of the Industrial Revolution. In Governing markets as knowledge commons, edited by Erwin Dekker and Pavel Kuchař, Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. 19–57.

Kramm, M. (2020). When a river becomes a person. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 21(4), 307–319.

Kuchař, P. (2016). Entrepreneurship and institutional change. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 26(2), 349–379.

Landes, W. M., & Posner, R. A. (1979). Adjudication as a private good. The Journal of Legal Studies, 8(2), 235–284.

Lavoie, D. (1986). The market as a procedure for the discovery and conveyance of inarticulate knowledge. Comparative Economic Studies, 28(1), 1–19.

Leeson, P. T. (2007a). Anarchy, monopoly, and predation. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics (JITE) / Zeitschrift Für Die Gesamte Staatswissenschaft, 163(3), 467–482.

Leeson, P. T. (2007b). Better off stateless: Somalia before and after government collapse. Journal of Comparative Economics, 35(4), 689–710.

Leeson, P. T. (2007c). Efficient anarchy. Public Choice, 130(1–2), 41–53.

Leeson, P. T. (2008a). How important is state enforcement for trade? American Law and Economics Review, 10(1), 61–89.

Leeson, P. T. (2008b). Social distance and self-enforcing exchange. The Journal of Legal Studies, 37(1), 161–188.

Leeson, P. T. (2014). Pirates, prisoners, and preliterates: Anarchic context and the private enforcement of Law. European Journal of Law and Economics, 37(3), 365–379.

Leeson, P. T., & Douglas Bruce Rogers. (2012). Organizing crime. Supreme Court Economic Review, 20(1), 89–123.

Leeson, P. T., & Harris, C. (2018). Wealth-destroying private property rights. World Development, 107, 1–9.

Leeson, P. T., & Peter, J. B. (2009). Two-tiered entrepreneurship and economic development. International Review of Law and Economics, 29(3), 252-259.

Lewis, P., & Runde, J. (2007). Subjectivism, social structure and the possibility of socio-economic order: The case of Ludwig Lachmann. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 62(2), 167–186.

Madison, M. J., Brett, M., Frischmann, M. R., Sanfilippo, & Katherine, J. S. (2022). Too much of a good thing? A governing knowledge commons review of abundance in context. Frontiers in Research Metrics and Analytics 7 (January).

McGinnis, M. D. (1999). Polycentricity and local public economies. University of Michigan Press.

McGinnis, M. D. (2011a). An introduction to IAD and the language of the Ostrom workshop: A simple guide to a complex framework. Policy Studies Journal, 39, 169–183.

McGinnis, M. D. (2011b). Networks of adjacent action situations in polycentric governance. Policy Studies Journal, 39(1), 51–78.

Menger, C. (2009). Investigations into the method of the social sciences. Mises Institute.

Murtazashvili, I., & Murtazashvili, J. (2015). Anarchy, self-governance, and legal titling. Public Choice, 162(3), 287–305.

Murtazashvili, I., & Murtazashvili, J. (2016). The origins of private property rights: States or customary organizations? Journal of Institutional Economics, 12(1), 105–128.

Murtazashvili, I., & Murtazashvili, J. (2019). The political economy of legal titling. The Review of Austrian Economics, 32(3), 251–268.

Murtazashvili, I., & Murtazashvili, J. (2020). Wealth-destroying states. Public Choice, 182(3), 353–371.

Murtazashvili, I., Murtazashvili, J., Weiss, M. B. H., & Madison, M. J. (2022). Blockchain networks as knowledge commons. International Journal of the Commons, 16(1), 108–119.

Ostrom, E. (1986). An agenda for the study of institutions. Public Choice 48(1).

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge University Press.

Ostrom, E. (2005). Understanding institutional diversity. Princeton University Press.

Ostrom, E. (2010). The institutional analysis and development framework and the commons. Cornell Law Review, 95(4), 807–815.

Radu, R. (2019). Negotiating internet governance. Oxford University Press.

Romero, M. R., & Virgil Henry Storr. (2023). Economic calculation and instruments of interpretation. The Review of Austrian Economics.

Scott, J. C. (1998). Seeing like a state. Yale University Press.

Storr, V. H. (2013). Understanding the culture of markets. Routledge.

Strandburg, K., Frischmann, B. M., & Madison, M. J. (2017). Governing medical knowledge commons. Cambridge University Press.

Stringham, E. P. (2015). Private governance: Creating order in economic and social life. Oxford University Press.

Talbot-Jones, J., & Bennett, J. (2019). Toward a property rights theory of legal rights for rivers. Ecological Economics, 164(October), 106352.

Taylor, C. (1995). Philosophical arguments. Harvard University Press.

Vachris, M., & Vachris, K. (2021). Entrepreneurship and governance in the Scotch whisky knowledge commons. In E. Dekker & P. Kuchař (Eds.), Governing markets as knowledge commons (pp. 195–216). Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Vicary, S. (1997). Joint production and the private provision of public goods. Journal of Public Economics, 63, 429–445.

Vogel, S. K. (2018). Marketcraft: How governments make markets work. Oxford University Press.

Wilson, B. J. (2020). The property species: Mine, yours, and the human mind. Oxford University Press.

Wilson, B. J. (2023). Property rights aren’t primary; ideas are. Journal of Institutional Economics, 19(2): 288–301.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Pavel Kuchař gratefully acknowledges the support of the Czech Science Foundation, grant nr. 22-28539 S.

We thank two anonymous referees for their insightful comments, as well as Ilia Murtazashvili for his editorial guidance. The paper benefitted from discussion at the 2022 Value-Based Approach to Economics Workshop in Venice as well as the feedback from the Philosophy, Politics, and Economics research group seminar at the Department of Political Economy at King’s College London, January 2023.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised to correct the second name, affiliation and e-mail address of second author.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dekker, E., Kuchař, P. Markets and knowledge commons: Is there a difference between private and community governance of markets?. Public Choice (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-023-01099-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-023-01099-0