Abstract

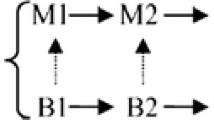

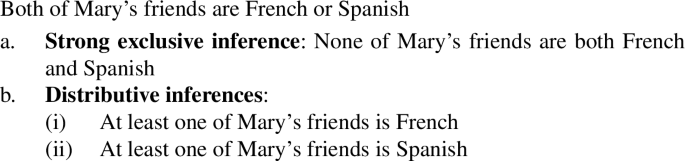

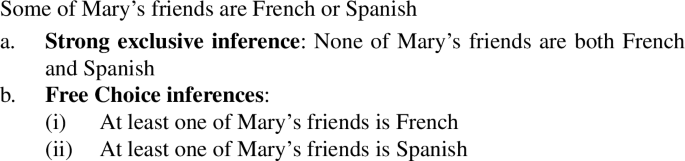

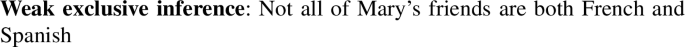

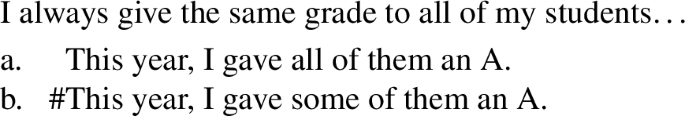

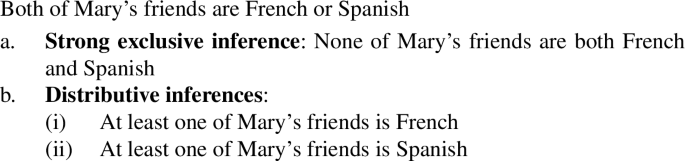

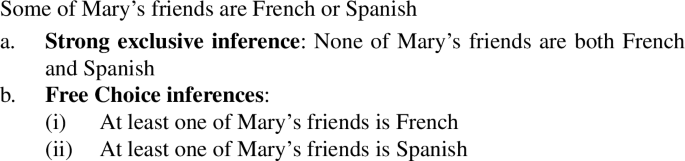

Denić (2018, 2019, To appear) observes that the availability of distributive inferences—for sentences with disjunction embedded in the scope of a universal quantifier—depends on the size of the domain quantified over as it relates to the number of disjuncts. Based on her observations, she argues that probabilistic considerations play a role in the computation of implicatures. In this paper we explore a different possibility. We argue for a modification of Denić’s generalization, and provide an explanation that is based on intricate logical computations but is blind to probabilities. The explanation is based on the observation that when the domain size is no larger than the number of disjuncts, universal and existential alternatives are equivalent if distributive inferences are obtained. We argue that under such conditions a general ban on ‘fatal competition’ (Magri 2009a,b, Spector 2014) is activated, thereby predicting distributive inferences to be unavailable.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

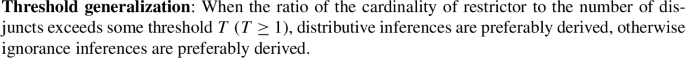

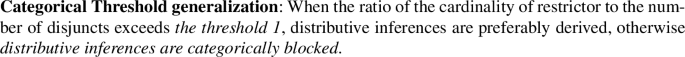

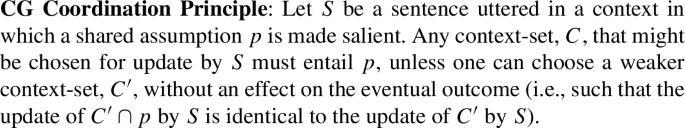

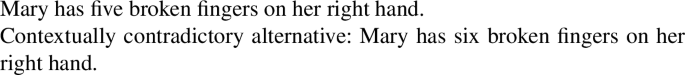

In Denić (To appear) she considers another generalization which is compatible with her observations:

-

(i)

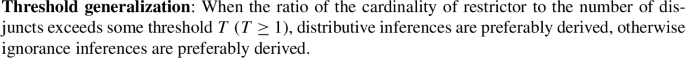

Since the objections we bring up against the generalization in (2) apply to the Threshold generalization just the same, we ignore the differences between them. Note that the generalization we argue for, in (5), bears some resemblance to the Threshold generalization, and our arguments for the generalization in (5) can also be understood as arguments for the following modified Threshold generalization (which is virtually equivalent to (5)):

-

(i)

-

(i)

Following the notation in (2), we use |D| and n throughout the paper to refer to the cardinality of the quantificational domain and the number of disjuncts, respectively.

The source of such an “ignorance inference” is something we return to in Sect. 6.3. For now, we can think of it as the inference that the speaker is ignorant about all alternatives that are not settled by her utterance—that she doesn’t know whether both her children live in Europe, whether they both live in the US, or whether some live in the US and some live in Europe. Ignorance inferences should be generated only when it is relevant where the children live; it seems reasonable that whenever sentences such as (4-a) and (4-b) are uttered the question where the children live would indeed be taken to be relevant. We think that this can be explained when thinking about possible QUDs, but we do not go into this for lack of space.

An alternative perspective on the infelicity of (6-a) and (7-a) is provided by the Logical Integrity generalization proposed by Anvari (2018), according to which a sentence S is infelicitous if it has an alternative which is contextually but not logically entailed by S. Because (6-a) and (7-a) contextually but not logically entail their DIs (before implicature computation), Logical Integrity captures their infelicity. However, Logical Integrity does not expect the absence of DIs when n ≥ |D| in general, and as a result cannot explain the categorical contrast in (4). See Bar-Lev (2023) for further discussion of Logical Integrity in the context of Denić’s data.

For that, one needs to look at the syntactic structure of the sentence as assumed already in Horn (1972), but very clearly articulated in Katzir (2007). There are many ways to see that this is the case, but one very obvious illustration comes from pairs of sentences that have identical basic meanings (before SIs are computed) and yet are associated with different SIs, e.g., some students passed the test and some or all students passed the test. See Chierchia et al. (2012) for an account.

We use the notation \(A \Rightarrow _{L} B\) when A logically entails B, and \(A \Rightarrow _{C} B\) when A contextually entails B (i.e., when B is true in all worlds in the context set where A is true).

Crnič et al. (2015) propose a way to derive DIs without the negation of ∀xPx and of ∀xQx. Their derivation is, however, dependent on the stipulation that the existential alternatives are not formal ones (or that they are pruned), which, as we have argued above, is difficult to reconcile with facts about intervention effects (or symmetry breaking). We achieve the same result without the stipulation. Furthermore, as we discuss in the following sections, our explanation for the CDG crucially rely on the assumption that existential alternatives are necessary for the derivation of DIs; this account is then incompatible with Crnič et al.’s proposal.

The possibility of deriving DIs by recursive \(\mathit {\mathcal {E}xh}_{}\) given the set of alternatives in Fig. 2 is problematic for Denić’s view, where the set of alternatives in Fig. 2 can only lead to ignorance inferences about the DIs (and the derivation of DIs is contingent on having the restricted set of alternatives in Fig. 1). In order to maintain the picture she argues for, then, recursive exhaustification would have to be blocked.

Bar-Lev and Fox (2020) have argued that FCIs are derived through an Innocent Inclusion procedure (part of an alternative definition of \(\mathit {\mathcal {E}xh}_{}\)). This makes the application of a second \(\mathit {\mathcal {E}xh}_{}\) operator redundant for the derivation of FCIs, but not for the derivation of DIs. Since our main focus here is DIs, we do not rely on Innocent Inclusion, though our proposal is compatible with it. If we adopt Innocent Inclusion, recursive exhaustification can still apply and its consequences will be exactly identical to what one gets without Innocent Inclusion where DIs are involved.

In other words, we would like to take the availability of FCIs in the sentences in (18) to suggest that they are in principle available for any sentence in which disjunction takes scope under a non-singular existential quantifier. This means that if the inferences are unavailable in certain other cases (or simply dispreferred), this must be due to external factors (e.g., parsing preferences) that do not enter into the computation of SIs.

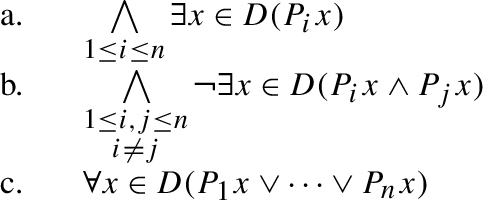

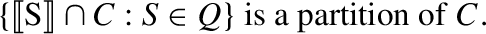

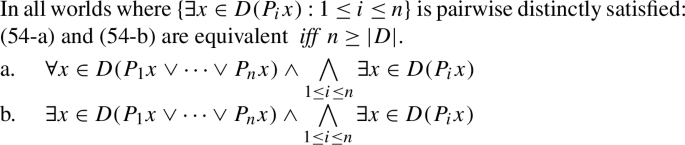

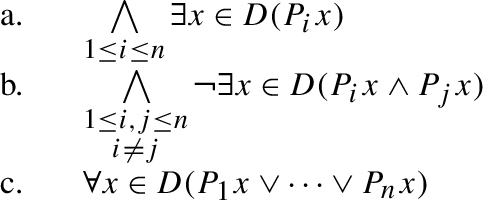

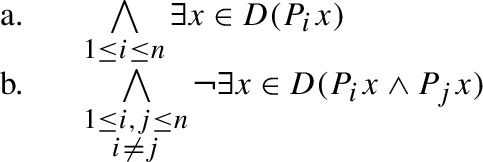

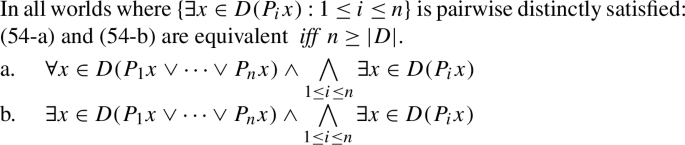

The entailment from (21-a) to (21-b) is again trivial. To show that the entailment goes in the other direction when n ≥ |D|, it is enough to show that in such a case the conjunction of (i-a) and (i-b) entails (i-c).

-

(i)

Note that (i-a) and (i-b) together entail that for every predicate \(P_{i}\), there is an individual in D which satisfies \(P_{i}\) and satisfies no other predicate. From this it follows that there are at least n individuals x in D for which \(P_{1}x \lor \cdots \lor P_{n}x\) is true. Now if (and only if) n ≥ |D|, (i-c) follows. The same holds if (i-b) is replaced with the weaker Distinctness assumption we introduce in Appendix A.

-

(i)

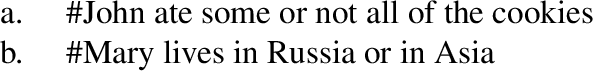

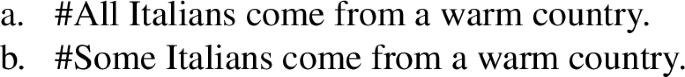

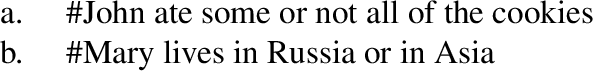

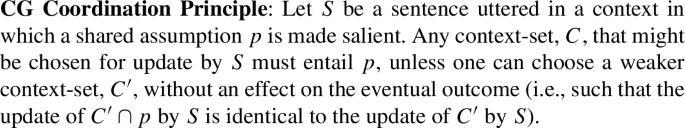

Some speakers report the intuition that (23-a) is not as bad as (23-b), and Magri (2011) discusses cases similar to (23) where the (a) variant is perfectly acceptable (see also Singh 2009, Spector 2014 for relevant ideas, observations and further challenges). In Appendix B, we sketch a way of dealing with these observations that is compatible with our proposal.

The accounts entertained in the literature for these cases of fatal competition presuppose that (23-a) and (23-b) are necessarily alternatives of each other. We note that this is not the case under all theories of alternatives. For example, Fox and Katzir (2011) argue that alternatives can only be derived by substitutions within a focused phrase. If this is the case, we would expect the sentences to improve when the subject is not dominated by a focus-marked constituent. We are not sure that this is the case (though see Singh 2009). In any event, the issue does not arise for our account of the CDG. For that account it is sufficient to look at the set of alternatives that are needed for deriving DIs and this, as we argue in Sect. 3, requires the entire set of alternatives in Fig. 2.

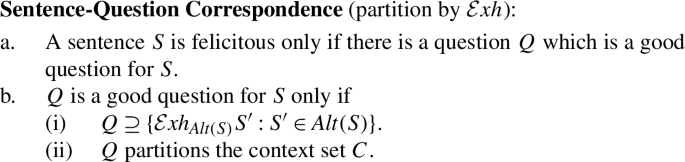

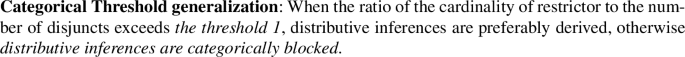

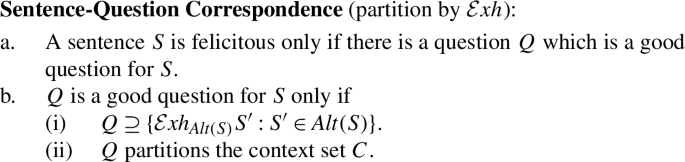

Note that our definitions are meant to block a situation in which two alternatives in Q are contextually equivalent. Such a situation would not be blocked if (25) is eliminated and (24-b-ii) is simply replaced by the following:

-

(i)

Thanks to Amir Anvari for pointing this out to us.

-

(i)

This is of course related to the fact that Rooth’s requirement demands that the focus value of S be a super set of the congruent question, which might be restated as the demand that the focus value of the sentence, after pruning, be identical to the question.

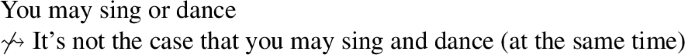

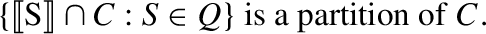

Fulfilling the requirement in (26) is both necessary and sufficient for fulfilling the one in (24). It is necessary because if Q partitions C and Alt(S) is a subset of Q, then Alt(S) must partition some subset of C. It is sufficient because if Alt(S) is a partition of some subset of C, then we can construct Q by adding a sentence to Alt(S) namely the negation of all sentences in Alt(S); constructed this way, Q is guaranteed to partition C.

In some cases \(\mathit {\mathcal {E}xh}_{}\) alone is not enough to derive a partition; see our discussion in Sect. 6.3.

This appears to make the wrong prediction that the scalar implicature for some will be obligatory, as we’ve abstracted away from pruning. This apparent prediction can be avoided independently of assumptions about pruning if we move to partition by \(\mathit {\mathcal {E}xh}_{}\) along the lines of Fox (2018). See Appendix A.

This wrong prediction can also be avoided by pruning or by a move to partition by \(\mathit {\mathcal {E}xh}_{}\), as we discuss in Appendix A.

There might also be cases which require pruning of all of the disjunctive alternatives, a possibility compatible with our proposal in Appendix A.

Applying a single \(\mathit {\mathcal {E}xh}_{}\) operator below K as well will also derive a partition.

This assumption in fact follows from Sentence-Question Correspondence as stated in (24); things become more complicated if Sentence-Question Correspondence applies to the output of pruning rather than to the set of formal alternatives, as we entertain in (45) (though as we discuss in Appendix A, assuming that pruning affects Question-Sentence correspondence is not at all necessary).

As far as we can tell, Denić (To appear) makes a parallel gradable prediction.

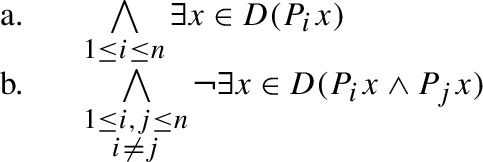

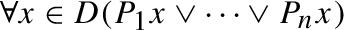

In order to demonstrate that (35) is predicted, we need to show that whenever m ≤ n the universal alternative (ii) follows from the DIs in (i-a) together with the strong exclusive inferences in (i-b). As we established, whenever this entailment goes through we predict DIs to be blocked.

-

(i)

-

(i)

Consider two arbitrary disjuncts \(P_{i}\) and \(P_{j}\) (where 1 ≤ i,j ≤ n). Given the DIs in (i-a) together with the exclusive inferences in (i-b), there must be at least one individual that satisfies \(P_{i}\) but not \(P_{j}\) (and vice versa). In other words, there can be no two predicates \(P_{i}, P_{j}\) such that the set of R-based equivalence classes containing individuals who satisfy \(P_{i}\) is the same as the set of R-based equivalence classes of individuals who satisfy \(P_{j}\). As a result, the number \(m'\) of R-based equivalence classes with individuals who satisfy at least one predicate is greater than or equal to the number of predicates n (i.e., \(n \leq m'\)). And of course the number \(m'\) of R-based equivalence classes with individuals who satisfy at least one predicate is smaller than or equal to the number of all R-based equivalence classes (i.e., \(m' \leq m\)). Now if the number of predicates n is greater than or equal to the number of all R-based equivalence classes m (i.e., m ≤ n), it follows that \(m=m'\) (because \(n \leq m'\), \(m' \leq m\), and m ≤ n). That is, every individual in every R-based equivalence class must satisfy at least one predicate. And if that’s the case, the universal alternative in (ii) follows. As in fn. 12, the same holds if (i-b) is replaced with the weaker Distinctness assumption we introduce in Appendix A.

-

(i)

Nothing changes, of course, if Mark was presupposed to be a roommate of Bill’s instead of Sally and Jane. In such a context too, we would have two equivalence classes. Thanks to Brian Buccola for pointing this out.

An alternative explanation for the unacceptability of (40) comes from work by Bassi et al. (2021) and Del Pinal et al. (To appear) (or the slightly modified version in Fox 2020), who argue that the contribution of \(\mathit {\mathcal {E}xh}_{}\) is presuppositional. If DIs are presuppositions, then whenever they are satisfied (40) is a contextual tautology.

Chemla and Romoli (2015) argue that probabilities are relevant for theories of SIs, but their claim is compatible with a modular view in which probabilistic considerations only enter at the level of ambiguity resolution, as we assume below.

As we did before, we ignore here the possibility of alternative pruning (in particular pruning of the alternative ∃x(Px∧Qx)); nothing substantial hinges on this.

Menéndez-Benito’s problem doesn’t only arise with modal quantification. For instance, (i) is odd if all the boxes that contain ice cream also contain cake, and vice versa.

-

(i)

-

(i)

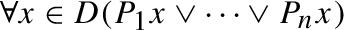

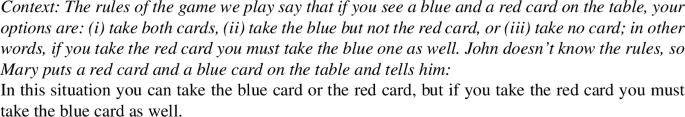

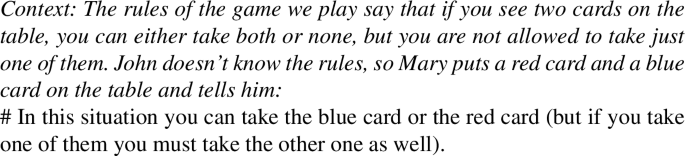

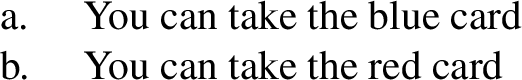

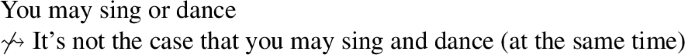

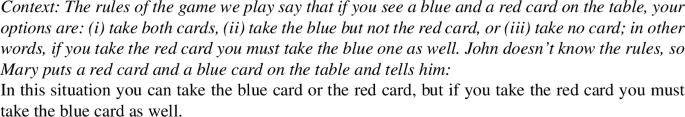

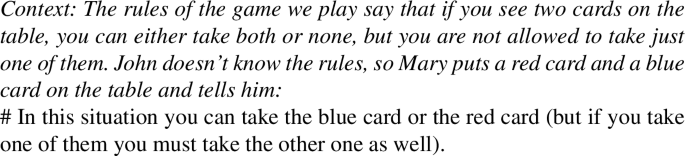

One may think that the unacceptability of (50) comes from exclusion of a conjunctive alternative—resulting in the inference that you cannot take both the blue card and the red card (at the same time); this inference has however been shown to be optional (as mentioned above), as in the following example (Simons 2005):

-

(i)

Moreover, one can see that exclusion of a conjunctive alternative is not what is at stake by considering minor variations on the same scenario where the rules permit the player to take both cards but also permit the player to take just one of the two cards (see fn. 35).

-

(i)

Menéndez-Benito (2010) herself assumes a stronger requirement than Distinctness according to which the FC inferences essentially are ∃x(Px∧¬Qx)∧∃x(Qx∧¬Px). Her stronger requirement however rules out the following example, which to us seems fine.

-

(i)

-

(i)

Of course, one would like to know where distinctness comes from. One possibility relies on Singh (2008). Singh argues for the following constraint:

-

(i)

As evidence he presents the following examples:

-

(i)

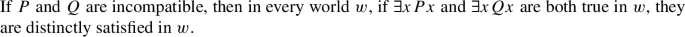

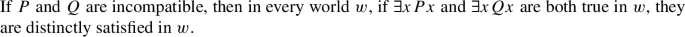

Note that Incompatibility implies Distinctness:

-

(i)

Incompatibility, as stated, will not immediately explain the original data Menéndez-Benito (2010) was concerned with, which does not involve disjunction, but rather Free Choice Items.

-

(i)

Note that exhaustifying over a simple disjunction of the form p∨q would require pruning the alternatives p and q, since otherwise exhaustification does not lead to a partition and (55) is violated.

One might think that DIs don’t need \(\mathit {\mathcal {E}xh}_{}\) for their derivation when they are contextually entailed by the prejacent, as is the case in (58). Two objections can be brought up against this possibility: (i) the deviant examples in (6-a) and (6-b) share the same property, so the reason these examples are infelicitous while (58) is fine will remain a mystery; (ii) the fact that (58) becomes infelicitous when |D| = n, as in (59), will also remain a mystery.

-

(i)

-

(i)

This bears some resemblance to the ideas in Schlenker (2012), developed to argue against the kind of blindness to CG crucial for our purposes (defended in Fox and Hackl 2006; Magri 2009a,b, and subsequent work). Note, though, that the correlation between level of entrenchment and acceptability observed by Spector is not expected in Schlenker’s architecture.

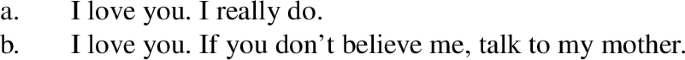

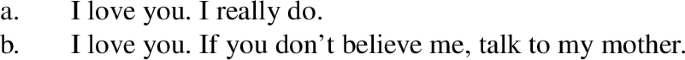

Under simple-minded renditions of Stalnaker’s model of assertion, the context-set is always updated as a consequence of assertion, from which it follows that once an assertion, A, entails HA, the speaker can no longer behave as if HA is not part of the CG. But this is obviously too strong, for various reasons, for example the observation that further assertions can be used to convince the addressee to accept A and add it to the CG. Consider, e.g.:

-

(i)

-

(i)

Much like the reduction of friction brings us closer to the idealized predictions about motion in a frictionless plane.

References

Alonso-Ovalle, Luis. 2005. Distributing the disjuncts over the modal space. In North East Linguistic Society (NELS), eds. L. Bateman and C. Ussery. Vol. 35, 1–12.

Anvari, Amir. 2022. Atoms and oddness. Talk given at Rutgers University, April 1, 2022.

Anvari, Amir. 2018. Logical integrity: From maximize presupposition! To mismatching implicatures. Unpublished manuscript.

Bar-Lev, Moshe E. 2023. Obligatory implicatures and the relevance of contradictions. Manuscript, TAU.

Bar-Lev, Moshe E., and Danny Fox. 2020. Free choice, simplification, and innocent inclusion. Natural Language Semantics 28: 175–223. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-020-09162-y.

Bar-Lev, Moshe E., and Danny Fox. 2016. On the global calculation of embedded implicatures. Poster presented at MIT Workshop on Exhaustivity.

Bassi, Itai, Guillermo Del Pinal, and Uli Sauerland. 2021. Presuppositional exhaustification. Semantics and Pragmatics 14: 11. https://doi.org/10.3765/sp.14.11.

Buccola, Brian, and Andreas Haida. 2019. Obligatory irrelevance and the computation of ignorance inferences. Journal of Semantics 36(4): 583–616. https://doi.org/10.1093/jos/ffz013.

Chemla, Emmanuel. 2009. Similarity: Towards a unified account of scalar implicatures, free choice permission and presupposition projection. Unpublished manuscript.

Chemla, Emmanuel, and Jacopo Romoli. 2015. The role of probability in the accessibility of scalar inferences. Unpublished manuscript.

Chemla, Emmanuel, and Benjamin Spector. 2011. Experimental evidence for embedded scalar implicatures. Journal of Semantics 28(3): 359–400. https://doi.org/10.1093/jos/ffq023.

Chierchia, Gennaro. 2004. Scalar implicatures, polarity phenomena, and the syntax/pragmatics interface. In Structures and beyond: The cartography of syntactic structures, ed. Adriana Belletti. Vol. 3, 39–103. Oxford: OUP.

Chierchia, Gennaro, Danny Fox, and Benjamin Spector. 2012. Scalar implicature as a grammatical phenomenon. In Semantics: An international handbook of natural language meaning, eds. Claudia Maienborn, Klaus von Heusinger, and Paul Portner. Vol. 3, 2297–2331. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110253382.2297.

Chomsky, Noam. 1995. Bare phrase structure. In Government and binding theory and the minimalist program, ed. Gert Webelhuth, 385–439. New York: Wiley.

Cremers, Alexandre, Ethan G. Wilcox, and Benjamin Spector. 2022. Exhaustivity and anti-exhaustivity in the RSA framework: Testing the effect of prior beliefs. Manuscript, Vilnius University, Harvard University, and Institut Jean Nicod. https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.2202.07023.

Crnič, Luka, Emmanuel Chemla, and Danny Fox. 2015. Scalar implicatures of embedded disjunction. Natural Language Semantics 23(4): 271–305. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-015-9116-x.

Del Pinal, Guillermo, Itai Bassi, and Uli Sauerland. To appear. Free choice and presuppositional exhaustification. Semantics and Pragmatics.

Denić, Milica. 2018. A new case of pragmatically deviant embedded disjunctions. In Semantics and linguistic theory, eds. Sireemas Maspong, Brynhildur Stefánsdóttir, Katherine Blake and Forrest Davis. Vol. 28, 454–473.

Denić, Milica. 2019. Langage et logique: Les cas des éléments à polarité négative et des implicatures scalaires. PhD dissertation, Université Paris Sciences et Lettres, École Normale Supérieure.

Denić, Milica. To appear. Probabilities and logic in implicature computation: Two puzzles with embedded disjunction. Semantics and Pragmatics.

Eckardt, Regine. 2007. Licensing or. In Presupposition and implicature in compositional semantics, eds. Uli Sauerland and Penka Stateva, 34–70. London: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230210752_3.

Fox, Danny. 2007. Free choice and the theory of scalar implicatures. In Presupposition and implicature in compositional semantics, eds. Uli Sauerland and Penka Stateva, 71–120. London: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230210752_4.

Fox, Danny. 2018. Partition by exhaustification: Comments on Dayal 1996. In Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung 22, eds. Uli Sauerland and Stephanie Solt, Vol. 1 of ZASPiL 60, 403–434. Berlin: Leibniz-Centre General Linguistics.

Fox, Danny. 2016. On why ignorance might be part of literal meaning—Commentary on Marie Christine Meyer. Talk given at the MIT workshop on exhaustivity.

Fox, Danny. 2020. Pointwise exhaustification and the semantics of question embedding. Manuscript, MIT.

Fox, Danny, and Martin Hackl. 2006. The universal density of measurement. Linguistics and Philosophy 29(5): 537–586. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-006-9004-4.

Fox, Danny, and Roni Katzir. 2011. On the characterization of alternatives. Natural Language Semantics 19(1): 87–107. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-010-9065-3.

Fox, Danny, and Roni Katzir. 2021. Notes on iterated rationality models of scalar implicatures. Journal of Semantics 38(4): 571–600. https://doi.org/10.1093/jos/ffab015.

Horn, Laurence R. 1972. On the semantic properties of logical operators in English. PhD dissertation, UCLA.

Kamp, Hans. 1974. Free choice permission. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society 74(1): 57–74. https://doi.org/10.1093/aristotelian/74.1.57.

Katzir, Roni. 2007. Structurally-defined alternatives. Linguistics and Philosophy 30(6): 669–690. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-008-9029-y.

Katzir, Roni. 2014. On the roles of markedness and contradiction in the use of alternatives. In Pragmatics, semantics and the case of scalar implicatures, ed. Salvatore Pistoia Reda, 40–71. London: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137333285_3.

Katzir, Roni, and Raj Singh. 2015. Economy of structure and information: Oddness, questions, and answers. In Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung, eds. Eva Csipak and Hedde Zeijlstra. Vol. 19, 302–319.

Klinedinst, Nathan Winter. 2007. Plurality and possibility. PhD dissertation, UCLA.

Kratzer, Angelika, and Junko Shimoyama. 2002. Indeterminate pronouns: The view from Japanese. In The third Tokyo conference on psycholinguistics, ed. Yukio Otsu, 1–25. Tokyo: Hituzi Syobo.

Lassiter, Daniel. 2012. Presuppositions, provisos, and probability. Semantics and Pragmatics 5: 1–37. https://doi.org/10.3765/SP.5.2.

Lewis, David. 1988. Relevant implication. Theoria 54(3): 161–174. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-2567.1988.tb00716.x.

Magri, Giorgio. 2009b. A theory of individual-level predicates based on blind mandatory scalar implicatures. Natural Language Semantics 17(3): 245–297. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-009-9042-x.

Magri, Giorgio. 2011. Another argument for embedded scalar implicatures based on oddness in downward entailing environments. Semantics and Pragmatics 4(6): 1–51. https://doi.org/10.3765/sp.4.6.

Magri, Giorgio. 2009a. A theory of individual-level predicates based on blind mandatory implicatures: Constraint promotion for optimality theory. PhD dissertation, MIT.

Menéndez-Benito, Paula. 2010. On universal free choice items. Natural Language Semantics 18(1): 33–64.

Meyer, Marie-Christine. 2013. Ignorance and grammar. PhD dissertation, MIT.

Romoli, Jacopo. 2012. Soft but strong. Neg-raising, soft triggers, and exhaustification. PhD dissertation, Harvard University.

Rooth, Mats. 1992. A theory of focus interpretation. Natural Language Semantics 1: 75–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02342617.

Sauerland, Uli. 2004a. On embedded implicatures. Journal of Cognitive Science 5(1): 107–137.

Sauerland, Uli. 2004b. Scalar implicatures in complex sentences. Linguistics and Philosophy 27(3): 367–391. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:LING.0000023378.71748.db.

Schlenker, Philippe. 2012. Maximize presupposition and Gricean reasoning. Natural Language Semantics 20(4): 391–429. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-012-9085-2.

Simons, Mandy. 2005. Dividing things up: The semantics of or and the modal/or interaction. Natural Language Semantics 13(3): 271–316. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-004-2900-7.

Singh, Raj. 2008. On the interpretation of disjunction: Asymmetric, incremental, and eager for inconsistency. Linguistics and Philosophy 31(2): 245–260.

Singh, Raj. 2009. ‘Maximize presupposition!’ and informationally encapsulated implicatures. In Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung, eds. Arndt Riester and Torgrim Solstad. Vol. 13, 513–526.

Spector, Benjamin. 2014. Scalar implicatures, blindness and common knowledge: Comments on Magri (2011). In Pragmatics, semantics and the case of scalar implicatures, ed. Salvatore Pistoia Reda, 146–169. London: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137333285_6.

Spector, Benjamin. 2006. Aspects de la pragmatique des opérateurs logiques. PhD dissertation, Paris 7.

van Rooij, Robert. 2002. Relevance only. In Proceedings of Edilog 2002.

von Wright, Georg Henrik. 1968. An essay in deontic logic and the general theory of action. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Acknowledgements

For helpful discussions and comments we thank Amir Anvari, Luka Crnič, Milica Denić, Roni Katzir, Benjamin Spector, the audience at the LINGUAE Seminar in Paris, as well as NALS editor Clemens Mayr, and especially Brian Buccola and an anonymous reviewer for very helpful suggestions. We also wish to acknowledge Keny Chatain’s Exh package (https://github.com/KenyC/Exh). His code was very helpful to us in understanding the consequences of various conjectures we made as we developed our proposal.

Funding

Moshe Bar-Lev was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Cukier-Goldstein-Goren Center for Mind and Language.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

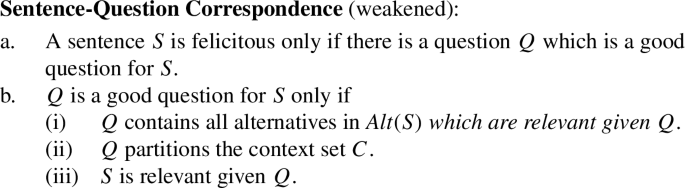

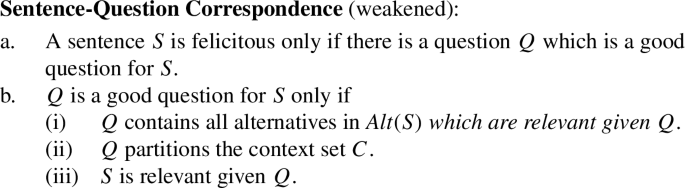

Appendix A: Pruning

In Sect. 6, we identified the question a sentence addresses with a superset of its set of formal alternatives. However, as is known since Horn (1972), some formal alternatives of a sentence can sometimes be ignored (‘pruned’), depending on the context. As we see below, the picture we drew in this paper becomes more complicated once we allow for pruning to shrink the set of alternatives against which Question-Sentence Correspondence is evaluated.

One way to avoid these complications could be to simply assume that Sentence-Question Correspondence applies as stated in (24) (i.e., considering all formal alternatives), even when alternatives are pruned. This assumption, however, raises empirical questions; as we pointed out in Sect. 6 (fn. 21), an empirical issue arises whenever an implicature is not associated with a weak alternative because the strong alternative is taken to be irrelevant. There is a simple way to avoid this issue by assuming a version of (24) which is based on the idea of partition by exhaustification from Fox (2018), as in (44).

-

(44)

(44) does not require the set of alternatives of a sentence to be a partition of some subset of the context set, but rather merely requires that it be a set which would yield such a partition if exhaustification applied. As a result, it does not mandate applying \(\mathit {\mathcal {E}xh}_{}\), nor does it put any constraints on pruning if \(\mathit {\mathcal {E}xh}_{}\) does in fact apply.

While this looks like a reasonable choice to make, in this appendix we would like to consider the possibility that pruning does affect Sentence-Question Correspondence, and that it requires the set of alternatives which are left after pruning to be a partition of some subset of the context set. In Sect. A.1, we aim to show that our proposal can be maintained even if Sentence-Question Correspondence is affected by pruning, once an apparently unrelated issue with FCIs is taken into account. In Sect. A.2, we further suggest a pruning-based restatement of our proposal which aims to account for the felicity of some sentences which have contextually contradictory alternatives.

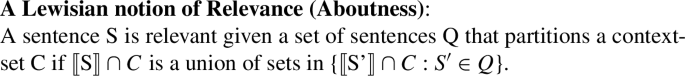

1.1 A.1 Pruning and distinctness

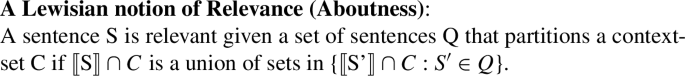

If Sentence-Question Correspondence is taken to be affected by pruning, then coming up with a specific theory of pruning becomes crucial. If pruning of any alternative is always possible, we can no longer rule out cases where some and all sentences are equivalent, as we will always be able to prune the equivalent alternative and avoid a violation of Sentence-Question Correspondence; and if pruning is never possible, then implicatures should always be obligatory, contrary to fact. So if Sentence-Question Correspondence applies after pruning, we need to weaken our constraint as in (45), which assumes that pruning is possible but limited to irrelevant alternatives, relying on Lewis’s (1988) notion of relevance in (46) (mainly following Magri 2009a,b, Fox and Katzir 2011):

-

(45)

-

(46)

Support for the assumption that (46) governs prunability comes from several sources. Magri argues (based on the data in (23)) that when two alternatives are contextually equivalent it’s impossible to prune one without the other, which is a consequence of (45) when relevance is defined as in (46). In the same spirit, Fox and Katzir argue that an alternative cannot be pruned when it’s in the Boolean closure of the set of alternatives which haven’t been pruned, which is also a consequence of (45) when relevance is defined as in (46).

Let us show first how this proposal explains the basic case of oddness discussed by Magri in (23). The contextual equivalence of some and all makes sure (just like in Magri 2009a,b) that the some alternative cannot be ignored once all is relevant. And as before, Q cannot contain both alternatives and still be a partition. Furthermore, (46) renders contradictions relevant (as noted by Lewis 1988), which is why \(\mathit {\mathcal {E}xh}_{}\)(some) (=some ∧¬ all) also cannot be ignored in this case (see Bar-Lev 2023 for elaboration on the effects of the relevance of contradictions on pruning).

The situation becomes more involved once we consider the case we are interested in, namely the disappearance of DIs when n ≥ |D|. First, since the universal and existential alternatives are not equivalent in this case before exhaustification applies, one might suspect that the existential alternative can be ignored so that it would not be able to block the derivation of DIs if n ≥ |D|. However, note that the existential alternative ∃x(Px∨Qx) is equivalent to the disjunction of the alternatives ∃xPx and ∃xQx. As mentioned above, relevance is closed under Boolean operations (conjunction, negation, and disjunction; see Fox and Katzir 2011); hence, it is impossible for ∃xPx and ∃xQx to be relevant without ∃x(Px∨Qx) being relevant as well (because ∃x(Px∨Qx)⇔∃xPx∨∃xQx). Since the relevance of ∃xPx and ∃xQx is a necessary ingredient for deriving DIs, it is impossible to derive DIs while pruning the existential alternative ∃x(Px∨Qx).

Second, in our discussion of the equivalence between (19) and (20), repeated in (47) and (48), we assumed that the strong exclusive inference in (47-a) is derived.

-

(47)

-

(48)

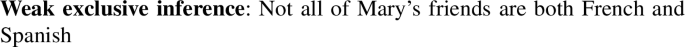

While there is evidence for the existence of the strong exclusive inference (see Chemla and Spector 2011), it is not very robust and is often not derived. Furthermore, the absence of DIs when n ≥ |D| does not seem to depend in any way on deriving the strong exclusive inference. However, the equivalence between (47) and (48) crucially relies on this inference. If (47-a) and (48-a) are replaced with the weak exclusive inference in (49), the equivalence no longer holds.

-

(49)

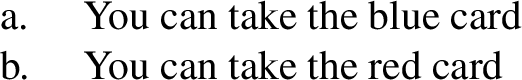

We’d like to suggest that this issue has to do with a known problem located elsewhere, namely that FCIs are stronger than the conjunction of the existential disjunctive alternatives. This issue has been brought up by Menéndez-Benito (2010). Consider the following example (Menéndez-Benito demonstrated the problem with her Canasta scenario using free choice items; here we replicate it with Free Choice disjunction instead):Footnote 31

-

(50)

The oddness of (50) is surprising since the sentence is true both on its ordinary meaning and its strengthened meaning. Specifically, the FCIs in (51) are true in the context:Footnote 32

-

(51)

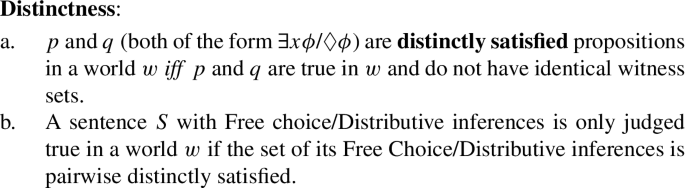

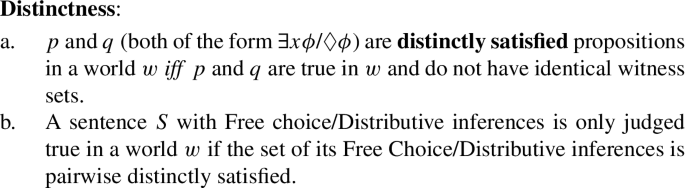

What seems to us to be the minimal assumption needed in order to capture the surprising oddness of (50) is the following:Footnote 33

-

(52)

(50) violates Distinctness: The set of worlds compatible with the rules where you take the blue card is the same as the set of worlds compatible with the rules where you take the red card.Footnote 34 Intuitively, in the case of (47) and (48), Distinctness requires that there would be one French friend (who is possibly also Spanish) and another Spanish friend (who is possibly also French). Under the distinctness assumption, (47) and (48) are equivalent even in the absence of the strong exclusive inference, since for (48-b) to be true there would have to be one French friend and another Spanish friend. But if that’s the case then (47-b) is true. More generally, the following holds:

-

(53)

Given Distinctness, then, our account of the CDG extends to cases which involve pruning (whatever may be the proper explanation for Distinctness; see fn. 36 for one possibility).

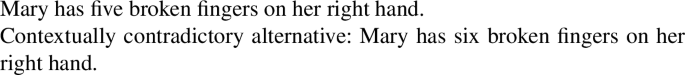

1.2 A.2 Felicity with contextually contradictory alternatives

As established, we predict that having contextual contradictions as alternatives should lead to infelicity. Note furthermore that this does not change once we allow for pruning to affect Sentence-Question Correspondence as in (45), since contradictions are always relevant and, as a result, cannot be pruned (Lewis 1988, Bar-Lev 2023). As noted in fn. 22, there are, however, felicitous sentences which have contextual contradictions as alternatives. Consider the following example brought up by Roni Katzir (p.c.):

-

(54)

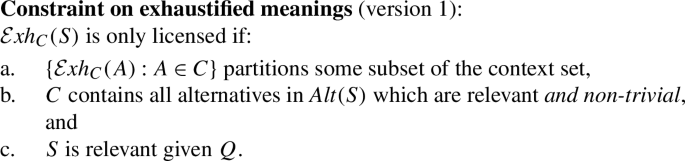

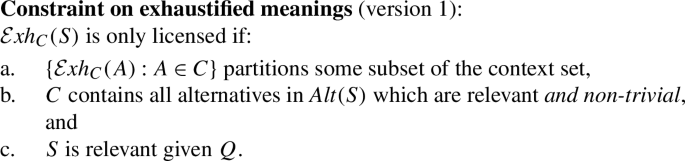

We acknowledge that this might be a serious problem for the perspective we proposed in this paper and suggest two tentative paths towards a solution. The first path latches on to a salient difference between the contextual contradictions leading to infelicity (or to blocking DIs) we discussed in this paper and (54), namely that in (54) the contextual contradiction is not the result of an application of \(\mathit {\mathcal {E}xh}_{}\). We could propose to exempt alternatives which are contextually trivial from the get go from even being considered. This, in turn, could be achieved by replacing the requirement to have Sentence-Question Correspondence (in any of its versions) with a constraint on exhaustified meanings, as follows:

-

(55)

This constraint requires that the pointwise application of \(\mathit {\mathcal {E}xh}_{}\) over the chosen set of alternatives be a partition, and that its domain must contain all relevant alternatives which are not trivial. (55) still explains the main facts we aim to capture in this paper if taken together with Magri’s assumption that applying \(\mathit {\mathcal {E}xh}_{}\) is obligatory. At the same time, it is compatible with the felicity of (54) because it allows pruning of alternatives that are contextually contradictory before exhaustification.Footnote 35

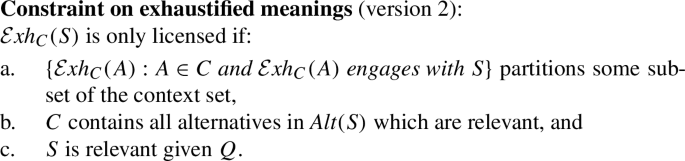

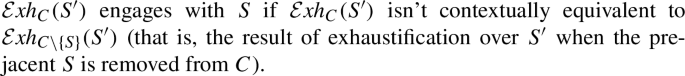

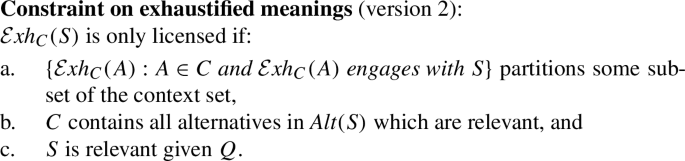

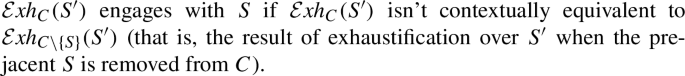

Our second alternative path towards a solution focuses on a less obvious property of (54), namely that the contradictory status of an (exhaustified) alternative does not follow in any way from the demands it imposes on the prejacent. This raises the following alternative.

-

(56)

-

(57)

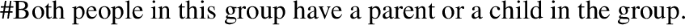

This weakening of the partition-demand can also capture an additional challenge to our proposal coming from the following example due to Bar-Lev (2023):

-

(58)

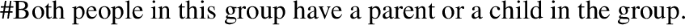

Bar-Lev points out that, just like the deviant examples brought up by Denić in (6-a) and (7-a), (58) is non-contradictory if DIs are derived and contradictory if ignorance inferences are derived (because (58) can only be true if there is at least one parent-child pair in the group, so one cannot believe (58) while being ignorant about the DIs). If it’s impossible to derive neither DIs nor ignorance inferences (as we assumed in this paper following Denić), one may conclude that (58) is fine because DIs can be derived.Footnote 36

However, Question-Answer correspondence predicts that the derivation of DIs should be blocked, because of alternatives like the one in (59); this alternative is a contextual contradiction in the case of (58), since it is impossible that there be a person in the group who has a parent in the group (∃xPx) without there being a person in the group who has a child in the group (∃xQx).

-

(59)

Note however that the version of the partition demand in (56) does not block the derivation of DIs here, since (59) remains a contradiction even when the prejacent is removed from the set of alternatives; in this case exhaustification of ∃xPx still entails the contextual contradiction ∃xPx∧¬∃xQx. In other words, this alternative does not engage with the prejacent and as a result does not need (by (56)) to be a member of the set that partitions a subset of the context set.

Appendix B: On the asymmetry between weak and strong alternatives

Consider again the two sentences in (23), repeated here in (60). We marked both sentences as infelicitous, following Magri (2009a,b) and Spector (2014). However, some speakers find that (60-a), although not entirely felicitous, is markedly better than (60-b).

-

(60)

This contrast intensifies in examples such as (61) (apparently due to Emmanuel Chemla, discussed in Singh 2009, Magri 2011, Schlenker 2012, Spector 2014), where the universal alternative is judged as entirely acceptable and the existential alternative is still infelicitous.

-

(61)

Our account of the CDG was crucially based on the assumption that both strong and weak alternatives are unacceptable in contexts where they are contextually equivalent (prior to exhaustification). If the account is right, the acceptability of (61-a) in a context where the first sentence in (61) is taken to be common ground (CG) is not expected.

We do not have a complete response to this problem and would like to simply express the hope that the ultimate resolution will be compatible with our proposal. Here we sketch a possible way of thinking about the problem that suggests to us that there might be reasons for optimism. Under our proposal, when the some and the all sentences are formal alternatives of each other and when they are contextually equivalent, both should be unacceptable. When things appear to deviate from this expectation, this, if we are right, must only be an appearance, one that occurs either because there is a parse of the relevant sentences where they are not formal alternatives of each other or because there is a way of thinking about the context where the alternatives are actually not contextually equivalent.

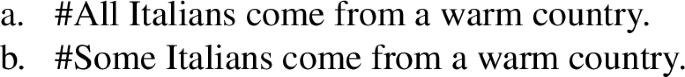

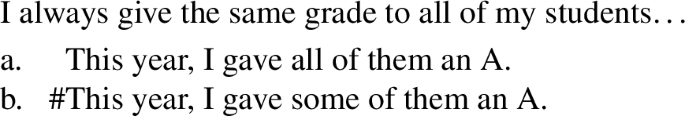

We pursue the latter possibility, building on an observation made by Spector about the nature of the distinction between (60) and (61) (see Singh 2009, who pursues the other possibility). Spector points out that the bit of the common ground that makes (60-a) and (60-b) contextually equivalent is deeply “entrenched”. Specifically, the belief that Italians all come from the same country is almost definitional, virtually on a par with the belief that bachelors are unmarried men. By contrast, the statement about the CG in (60) (that I always give the same grade to all of my students), although a possible characterization of the CG, is not as deeply entrenched.

Imagine, as suggested by Spector, that the contrast between the sentence with a universal and an existential quantifier weakens the more entrenched the homogeneity assumption (HA) is (the bit of common ground that makes the pre-exhaustified universal and existential alternatives contextually equivalent). To capture such a distinction in levels of entrenchment, one might be tempted to think of the CG as containing information about degrees of belief (as in, e.g., Lassiter 2012). Instead, we would like to continue to think of the CG in non-gradable terms: the more entrenched a bit of shared belief is, the more participants in the conversation are likely to take it as CG. In other words, what we would like to claim (following Spector) is that it could sometimes be difficult to ensure that some bit of information explicitly introduced is going to enter the CG. The introduction of information might make it clear that various participants in the conversation believe it to be true. It might even ensure that they all believe it to be true. But this does not necessarily ensure that they thereby fix on the idea that the utterance would be interpreted with this shared belief as CG, especially if exactly the same results could be achieved without taking this shared belief to be part of the CG.Footnote 37

2.1 B.1 All sentences sometimes acceptable despite the introduction of HA

We would like to suggest that the utterance in (61-a) is acceptable simply because we can understand it as one that is intended to be interpreted against a CG that does not already entail HA. Having a speaker assert HA (without a hearer protesting) might not be sufficient to ensure that HA enters the CG. A speaker might, still, intend for the (a) sentence to be interpreted against a weaker CG that does not entail HA, especially as this speaker can achieve exactly the same results without HA as CG; specifically, the speaker can expect to achieve a CG where HA is established as a consequence of the assertion. (Remember that the all sentence entails HA: saying that all students received an A entails that they all got the same grade.)Footnote 38

The remaining problem is to explain why the (b) sentence is unacceptable under the same circumstances, and why DIs are categorically blocked when |D| is not greater than the number of disjuncts.

2.2 B.2 Some sentences never acceptable with the introduction of HA

To understand why this strategy might not be available for the (b) sentence, it is useful to begin with the reasoning outlined in Magri’s work. Specifically, when (b) is uttered, we can assume with Magri that there is an obligatory \(\mathit {\mathcal {E}xh}_{}\) that is inserted at the clausal level (below K if Meyer’s approach to ignorance inferences is adopted). If the all alternative is not pruned, we will have a straightforward explanation for unacceptability: the resulting meaning will contradict a shared belief, namely HA, the belief that all of the students got the same grade. This will lead to an anomaly despite our assumption that the shared belief need not be part of the CG. So, a parse in which the all alternative is not pruned is unacceptable for trivial reasons.

The more challenging case is the parse in which the all alternative is pruned. In a context in which some and all are contextually equivalent, such a parse will be unavailable for the reasons articulated by Magri. (Specifically, pruning an alternative is only possible if the alternative is taken to be irrelevant given the topic of conversation. But this is impossible given that the some alternative is taken to be relevant and that relevance is taken to be closed under contextual equivalence.) But this reasoning is not obviously helpful, given our assumption that the CG need not entail HA (despite the fact that HA is introduced as a shared belief). We would like to suggest that there is nevertheless a potential difficulty with the utterance of the (b) sentence even when the all alternative is pruned.

We would like to suggest that in general speakers and hearers need to be able to coordinate on the goal of the assertion—the CG that the speaker intends to achieve with her final assertion (CG\(_{\text{goal}}\)). The difficulty we see with the utterance of the (b) sentence is related to this requirement. Does the speaker intend for CG\(_{\text{goal}}\) to be a CG that entails HA? If so, this would not be achieved by simple (Stalnakerian) update given the necessary assumption that HA is not part of the input context-set. If not, what kind of CG is the speaker interested in establishing? It is hard to see how the speaker and the hearer could coordinate on the goal of the assertion.

The situation with the all sentence is very different, as already mentioned. With the all sentence a decision to interpret the sentence against a CG that does not entail HA leads to exactly the same CG that would be reached if the sentence is interpreted against a CG that does entail HA, hence there is no difficult coordination problem to solve. This line of reasoning can be simplified with the following principle:

-

(62)

This line of reasoning accounts for the disappearance of the contrast in (61) and crucially for the observation that it is weakened the more entrenched HA is. Specifically, if we can’t conceive of a world in which HA is false, the relevant principles of grammar will reveal themselves. So the more entrenched HA is, the closer our observations will be to the idealized prediction.Footnote 39

2.3 B.3 Back to the CDG

What remains is to explain why the CDG feels like a categorical constraint. Here we would simply like to refer to the level of entrenchment involved. It is simply impossible to imagine possibilities in which the most basic laws of arithmetic do not hold true. And, as we’ve seen, imagining such possibilities would be necessary to make the all and the some alternatives not equivalent (when inferences about each other are ignored) when |D| is not greater than the number of the disjuncts. More specifically, it is simply impossible for the existential FC meaning to be true while the universal alternative is false: if one of my two children lives in Europe and one lives in North America, it is impossible (if two means two) that the universal alternative is false, that is, that I have a child who lives neither in Europe nor in North America.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Bar-Lev, M.E., Fox, D. On fatal competition and the nature of distributive inferences. Nat Lang Semantics 31, 315–348 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-023-09210-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-023-09210-3