Abstract

Until 1996, mobility costs for football players in Europe were high. Clubs retained rights to players when their contracts expired and were able to prevent free agents from signing with new clubs. In a 1995 verdict known as the “Bosman Ruling," the European Court of Justice determined that the rules governing player transfers between clubs violated the Treaty of Rome provision of labor mobility across European Union countries and must be revised, reducing the requirements players must meet to change clubs. This paper makes two contributions. First, it estimates a gravity model of bilateral player migration flows and stocks using a Poisson Pseudo Maximum Likelihood estimator, obtaining results similar to international trade: players are more likely to move to a league that is closer to their native country, one where their native language is spoken, and one where their compatriots also compete. Second, it finds that the measured effect of distance on depressing migration flows fell by about one-third of its pre-Bosman level after the 1995 ECJ ruling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in OPENICPSR at https://www.openicpsr.org/openicpsr/project/112661/version/V1/view.

Notes

This is in contrast to the evolution of the effects of distance on merchandise trade flows, which Disdier and Head (2008) show decreased until 1970, but remained roughly stable thereafter.

The ruling in the Bosman case was legally decided by a player’s right to migrate freely within the various member states, with R. F. C. Liège’s refusal to grant Bosman his desired transfer after his contract expired interpreted as a barrier to migration. In paragraph 96 of their decision, the ECJ stated “Provisions which preclude or deter a national of a Member State from leaving his country of origin in order to exercise his right to freedom of movement therefore constitute an obstacle to that freedom even if they apply without regard to the nationality of the workers concerned..." Therefore, it did not matter that R. F. C. Liège’s refusal to allow Bosman to sign for US Dunkerque was independent of his Belgian nationality. Simply being Belgian entitled him to the right to play for any other team in the European Union since he was out of contract. As a result, the rule change forbidding transfer fees for free agents was entirely scrapped, enabling free agents to transfer between any two clubs with no required transfer fee, even if those clubs were in the same country.

Unlike some professional sports leagues where players have contracts with those leagues and teams are able to trade those contracts, European football transfers require the 1) the buying and selling teams coming to an agreement on the transfer fee and 2) the transferring player to agree to terms with the new team. If the player does not wish to move, he can continue with his original contract and original team.

The leagues included are the top divisions in Austria, Belgium, Denmark, England, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland.

However, as is common in professional sports, career duration is highly variable across players. Roughly one-third of players in the dataset appear for only a single year. One of the causes of this churning is that the composition of teams within a league changes each year due to the promotion (relegation) of teams from the second (first) division to the first (second) that did well (poorly) in the prior year. The teams that are relegated (promoted) generally bring a majority of their players down (up) to the next division with them, and, as a result, those players exit (enter) the sample. Players will also drop out of the dataset if they move to a league that is outside of these fourteen countries. However, if and when they return to one of these fourteen countries, they reappear in the data. On the other end of the longevity spectrum, 14% of players appear in at least nine separate years.

The exceptions to this are Denmark, Sweden, and Norway where the more extreme weather precludes grass sports during the winter months. In those countries where summers are more mild, the leagues begin in the spring and conclude in the fall.

The data is further complicated because players who move in January (or late in the summer transfer window) may appear as members of more than one team within the same season. For example, American goalkeeper Kasey Keller played for the English team Tottenham at the beginning of the 2004–2005 season. At the end of the summer transfer window, he was loaned (a temporary agreement whereby a player who has a contract with one team plays for a short spell with another, a tool often used by teams to get youth players experience, but also the way in which US Dunkerque attempted to sign Jean-Marc Bosman) to Southampton. He played for Southampton for the remainder of the fall but then signed with German team Borussia Mönchengladbach in January of 2005. As a result, Keller appears in the data three times for the 2004–2005 season. Observations for some countries, but not all, contain the number of games in which the player participates. If the coverage across countries were accurate, I would keep the observation for the team for which the player makes the most appearances. However, for some countries such as France, the number of games played is unrecorded. By keeping the observation for which the most games are played, countries like France for which that data is missing would be dropped disproportionately relative to other countries. In order to maintain as representative of a sample as possible, while also reducing the number of observations for each player-year pair to one, \(x-1\) observations for each player-year pair that is observed \(x>1\) times are randomly dropped.

“EU" here denotes the set of countries whose top division is covered in the data. The overlap with European Union membership is not perfect but very close: most of these fourteen countries are EU members for the duration of the sample (the exceptions being Norway and Switzerland, whose citizens nonetheless enjoy the freedom of mobility within the EU through the Schengen Agreement, along with Austria prior to 1995, Portugal prior to 1986, Spain prior to 1986, and Sweden prior to 1995), whereas almost all countries whose leagues are not covered are not members, with few exceptions for the last years of the sample (such as Bulgaria joining in 2007 and Cyprus joining in 2004).

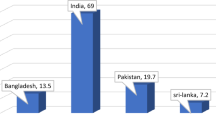

In addition to the fourteen countries whose leagues are covered, the remaining four countries are Argentina (1.7%), Brazil (3.8%), Ireland (1.0%), and Yugoslavia (3.4%). Yugoslavia broke up into Croatia, Slovenia, Macedonia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, and Montenegro in 1992, at which point each player in the dataset had already been born. Therefore, players who now identify as any of these nationalities are classified as Yugoslavian.

Note the roughly geographic arrangement in countries moving down the vertical axis or right along the horizontal axis: the labels begin on the Iberian peninsula, move across the English Channel through the Benelux countries, through central Europe, then Scandinavia, and then out to the most geographically distant of the included leagues: Greece.

CEPII does not contain bilateral distance measures for Yugoslavia. Instead, bilateral distances for Yugoslavia are replaced with the modern values for Bosnia and Herzegovina due to that country’s central location within the former bloc.

A similar issue emerges here with regards to measuring population shares of the countries that were established upon the dissolution of Yugoslavia. The share of “Yugoslavians" living in Germany in 2006, for example, is calculated as the number of Croatian, Slovenians, Macedonians, Bosnians, Herzegovinians, Serbians, and Montenegrans living in Germany in that year divided by the German population. Conversely, the share of Germans living in “Yugolsavia" in 2006 is calculated as the number of Germans living in any of the countries that previously constituted Yugoslavia, divided by the sum of their populations.

See Helpman et al. (2008) for a description of a sparse trade matrix characterized by many zeros. Using a sample of 158 countries, they find that roughly 50% of country pairs do not trade at all with one another in a given year, with these zero flows occurring disproportionately between smaller countries. Baldwin and Harrigan (2011) provide a theoretical justification for zero flows.

The number of teams per league varies from a low of 10 to a high of 22. The size of the average roster increases over time, with most teams employing around 30 players in a given year by the end of the sample.

With regard to prestige, the top teams in each country in one season compete in European-wide tournaments the following season. If a league’s teams do particularly well in a given year, the exposure that comes along with that success might increase the relative attractiveness of that league and desirability of playing there.

For example, consider trade between the United States and two partner countries: Spain and Australia. Because Spain is embedded on the European continent and has an abundance of nearby neighbors with which its residents can trade, whereas Australia is an isolated landmass with few surrounding neighbors, including multilateral resistance in a model of US trade would generate larger trade flows with Australia relative to Spain compared to a model in which it is absent.

Because of league restructuring, it would be insufficient to include just origin and league country fixed effects. For example, Denmark began the sample with 16 teams in its domestic league. It experienced two episodes of downsizing, resulting in only 10 teams participating from 1991 until 1995. Beginning in 2006, the league expanded back up to 12 teams. Including only league country fixed effects does not account for the changes in demand for players that resulted from these contractions and expansions. These time-varying country-specific fixed effects also control for the heterogeneous evolution of average wages across countries.

Melitz and Toubal (2014) estimate that sharing a common language increases bilateral trade volumes by 67%. For goods trade, two countries sharing a common language may be less important if the trading parties can use English as the lingua franca A businessperson from Germany will likely be able to communicate with a Chinese colleague by speaking English, and therefore trade flows between countries that do not share an official language are not dampened too severely. For an American consumer to purchase and enjoy an iPhone assembled in and imported from China, speaking or understanding Chinese is not required. However, for a football player in the public eye who might be expected to speak to the press in a non-native language, not being able to communicate effectively might serve as a strong deterrent to making that move. For an Argentine deciding between offers to play in France or Spain, approximately equidistant to his native country, Spain might be more attractive due to his ability to more easily communicate and fit in culturally.

Although the fourteen countries whose leagues are featured constitute less than 10% of all countries in the dataset, 77% of players are native to those 14 countries.

References

Agrawal D, Foremny D (2019) Relocation of the rich: migration in response to top tax rate changes from Spanish reforms. Rev Econ Stat 101(2):214–232

Anderson J, van Wincoop E (2003) Gravity with Gravitas: a solution to the border puzzle. Am Econ Rev 93(1):170–192

Baldwin R, Harrigan J (2011) Zeros, quality, and space: trade theory and trade evidence. Am Econ J Microecon 3(2):60–88

Binder J, Findlay M (2012) The effects of the Bosman ruling on national and club teams in Europe. J Sports Econ 13(2):107–129. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527002511400278

Correia S, Guimarães P, Zylkin T (2019a) PPMLHDFE: fast poisson estimation with high-dimensional fixed effects. Mimeo, Federal Reserve Board

Correia S, Guimarães P, Zylkin T (2019b) Verifying the existence of maximum likelihood estimates for generalized linear models. Mimeo, Federal Reserve Board

Disdier A-C, Head K (2008) The puzzling persistence of the distance effect on bilateral trade. Rev Econ Stat 90(1):37–48

Fally T (2015) Structural gravity and fixed effects. J Int Econ 97(1):76–85

Frick B (2009) Globalization and factor mobility: the impact of the “Bosman-Ruling’’ on player migration in professional soccer. J Sports Econ 10(1):88–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527002508327399

Glennon B, Morales F, Carnahan S, Hernandez E (2022) Does employing skilled immigrants enhance competitive performance? Evidence from European Football Clubs. NBER Working Paper 29446

Helpman E, Melitz M, Rubinstein Y (2008) Estimating trade flows: trading partners and trading volumes. Q J Econ 123(2):441–487

Judgment of 15 December 1995, Union Royale Belge des Soci‘et‘es de Football Association ASBL vs. Jean-Marc Bosman, C-415/93, EU:C:1995:463, paragraph 114

Kleven H, Landais C, Saez E (2013) Taxation and international migration of superstars: evidence from the European Football Market. Am Econ Rev 103(5):1892–1924

Marcén M (2016) The Bosman ruling and the presence of native football players in their home league: the Spanish case. Eur J Law Econ 42:209–235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-016-9541-4

Mayer T, Zignago S (2011) Notes of CEPII’s distances measures: The GeoDist database. CEPII Working Paper 2011-25

Melitz J, Toubal F (2014) Native language, spoken language, translation and trade. J Int Econ 93(2):351–363

Özden Ç, Parsons C, Schiff M, Walmsley T (2011) Where on earth is everybody? The evolution of global bilateral migration 1960–2000. World Bank Econ Rev 25(1):12–56

Santos Silva J, Tenreyro S (2006) The log of gravity. Rev Econ Stat 88(4):641–658

Santos Silva J, Tenreyro S (2011) Further simulation evidence on the performance of the Poisson pseudo-maximum likelihood estimator. Econ Lett 112:220–222

United Nations Department of Economics and Social Affairs (2017) 2017 International Migration Report: Highlights

Vasilakis C (2017) Does talent migration increase inequality? A quantitative assessment in football labour market. J Econ Dyn Control 85:150–166

Acknowledgements

The author thanks participants at the JMU Microeconomics workshop, those who offered comments at the Southern Economics Association Annual Meeting, and two helpful referees. All errors are my own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The author has no competing interests to state nor funding sources for this project to report.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Hamilton, B. Gravity in the Beautiful Game: Labor Market Liberalization and Footballer Migration. Open Econ Rev (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-023-09733-6

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-023-09733-6