Abstract

Introduction

Unwanted exposure (UE) to sexual content may have important consequences on children/adolescents’ psychosexual development. Our objective was to analyze UE to online pornography, parental filter use, type of sexual contents seen, emotional/behavioral reactions, and UE as positive/traumatic experience in Spanish adolescents and to examine these experiences and reactions depending on the type of sexual content.

Methods

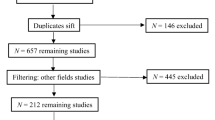

In 2020, 500 Spanish teenagers (13–18 years) completed an ad hoc questionnaire for the evaluation of different dimensions involved in UE to sexual contents, such as those mentioned in the study objectives.

Results

A high frequency of UE (88.2%) is observed. Regarding the kind of scenes, naked people, straight porn, and people showing genitals are the most unexpectedly seen. Adolescents used to react to the UE closing the window and deleting sexual materials. A greater predominance of negative emotions was revealed, and another noteworthy result is related to the role played by type of sexual content and gender. Gay scenes and being woman increased the probability of living the experience as non-positive, and being woman and viewing naked people/BDSM scenes/under-age sex were associated with reactions of rejection.

Conclusions

This study contributes significantly to the knowledge of UE to online pornography in adolescents. It provides valuable information about the role played by the type of sexual content seen and the gender in the diverse reactions/experiences derived from the UE to pornography.

Policy Implications

This topic, that is, involuntary exposure to online sexual material in adolescents, should be included in affective-sexual education and prevention programs at early ages, so that children/adolescents are already trained in healthy sexuality when facing this type of content for the first time. These programs, adjusted to the reality of our adolescents, will minimize the negative impact that UE may have on their psychosexual development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Use of the Internet

Use of the Internet has become increasingly significant not only in adults but also in children and adolescents’ lives. The rates are even higher among this latter group. Recent data revealed that 91% of children aged 5–10 years use the Internet, and this percentage increases to 93–98% at the age of 10–16 years (Childwise, 2017; Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE), 2020). Likewise, the time spent by males on the Internet is higher than that reported by females (Ballester-Arnal et al., 2017a). There is no doubt about the central role played by new information and communication technologies (ICT) in people’s lives and how the Internet has turned into a core and essential tool changing the way people communicate and exchange information and offering diverse advantages (Best et al., 2014; Brown & Bobkowski, 2011; Mifsud, 2009). Adolescents are one of the greatest beneficiaries of an appropriate use of ICT and the Internet, which have been incorporated as natural/habitual means of communication, entertaining as well as learning opportunities (Mitchell et al., 2007). However, not only a wealth of opportunities and benefits is provided by the Internet but also some potential dangers, making adolescents particularly vulnerable on account on their generalized use of the Internet (9.5 out of 10 adolescents use the Internet) (Madigan et al., 2018) along with the growing time spent in the virtual digital world (DeMarco et al., 2017). Among the potential risks associated with Internet use (e.g., meeting dangerous people online, falling victim to harassment and bullying) (Best et al., 2014; Finkelhor et al., 2000; Ybarra & Mitchell, 2004), the ease with which they can seek out pornographic material at an early age (Ballester-Arnal et al., 2016, 2021, 2023) and the unwanted exposure (UE) to online sexually explicit material are also included (Ey & Cupit, 2011; Hornor, 2020; Kloess et al., 2014; Livingstone et al., 2011).

Unwanted Exposure to Sexual Material

UE to sexual material can be defined as “without seeking or expecting sexual material, being exposed to pictures of naked people or people having sex when doing online searches, surfing the Web, and opening e-mail or e-mail links” (Mitchell et al., 2003, p. 337). Moreover, the UE may also take place through the interaction with other Internet users considering that there has not been a previous choice on that exposure; that is, the person has not chosen to be exposed to sexual content (Bryant, 2009). Thus, as a whole, the term UE could refer to all those situations in which people receive unwanted sexual solicitations, are harassed online, or exposed to sexual content inadvertently (Wolak et al., 2007).

In this regard, it is worth mentioning that the worry about this phenomenon and the possible harms (immediate or short term perceived) derived from being exposed to online pornography have become widespread, above all taking into account that UE may have a greater impact on adolescents than wanted exposure has (Wolak et al., 2007). Although this is a controversial issue that needs further evidence on the possible beneficial or harmful effects of cybersex, the concern increases according to recent data on the number of youths who are exposed to online pornography that they did not wish to see. These numbers range between 23 and 80% (Ballester-Arnal et al., 2016; Bernstein et al., 2022; Flood & Hamilton, 2003; Hardy et al., 2013; Mitchell et al., 2003, 2007) showing a prevalent phenomenon and being the adolescents aged 15–17 years the most involuntarily exposed.

It has not been easy to determine the general trend in UE data so far, and even some studies carried out on this topic offer contradictory results. On the one hand, an upward trend over time seems to be found by some authors (Mitchell et al., 2007; Wolak et al., 2007), whereas other studies show a decline in UE to sexual material (Jones et al., 2012; Mitchell et al., 2014). Considering this information, there seems to be some variability between contexts, and the different content control policies on the Internet in different countries could play a relevant role. Despite these contradictions, there is no doubt that many adolescents are unexpectedly exposed to online pornography every year (Collins et al., 2017; Wolak et al., 2006). These data are especially relevant when considering that UE may be a negative experience for adolescents (Ševčíková et al., 2015) and even have negative effects on their psychosexual development (Peter & Valkenburg, 2008), because of an insufficient developmental readiness and/or a lack of cognitive capacity and intrapsychic or cultural scripts to properly understand the global situation they have seen unexpectedly (Collins et al., 2017; Finkelhor et al., 2000; Ševčíková et al., 2015; Wolak et al., 2007). In addition to this, it is also necessary to consider another relevant concept in this context, such as risk attenuation, understood as “the adolescent’s inability to use critical thinking and decision-making skills to discern more risky from less risky behavior” (Delmonico & Griffin, 2008; pp. 435). Some adolescents lack the ability to decipher risk needed to discern online interactions as well as contents in a safe and healthy way, and this deficiency in deciphering risk raises great concerns in light of the potential dangers (Paat & Markham, 2021). All of these, without forgetting the importance of the sexual content seen as well, which is most often unrealistic and biased (Maes & Vandenbosch, 2022), and therefore may have detrimental implications for some adolescent’s sexual attitudes and behaviors although more knowledge about the processes that underlie the relation between pornography use and sexual attitudes and behaviors, such as sexual aggression, are necessary (Peter & Valkenburg, 2016).

Possible Effects Derived from Exposure to Online Sexual Material

Some authors list among the effects derived from the exposure to online sexual content in the media, changes in the sexual attitudes and behaviors (Harris & Christina, 2002), which could be explained within the framework of Bandura’s social cognitive theory. Much social learning takes place, intentionally but also unintentionally, through models in the immediate environment (Bandura, 2002, 2009). Therefore, this learning of human values, attitudes, behaviors, etcetera, could be extended to what is seen on the Internet, since it is not unreasonable to consider it as an immediate environment.

The cited framework may explain some of the consequences that the viewing of online pornography, in this case accidental, may have on adolescents. The scientific literature reviewed indicates that in the long term, and especially among children, UE could encourage sexual values and beliefs related, for example, to a greater acceptance of casual sex and perceptions that sex is more frequent or prevalent (Ward, 2016), objectification of sexual partners (Rissel et al., 2017), violent sexual behaviors (Foubert et al., 2019), unhealthy attitudes about sexual consent (Rothman et al., 2020), sexual concerns, sexual promiscuity, excessively early age of onset in sexual relations, intense emotional reactions, poor self-concept, and even in the short term, feelings of disgust, repulsion, shame, and shock (Aisbett, 2001).

However, this is a controversial issue since the negative effects are debatable, short term, or unknown in extent, and more studies on the possible beneficial or harmful effects of cybersex are necessary, given the number of adolescents inadvertently exposed to online pornography. This study will try to expand on the previous findings by examining current data about UE to online pornography at early ages in Spain, given the important knowledge gap about this in our context. Although a recent study conducted in Spain (Ballester-Arnal et al., 2023) indicates that 97.3% of adolescents (under 18 years old) report having consumed pornography, there are no studies that focus on involuntary exposure at these ages. We have only found one study in the reviewed literature but carried out with adults (González-Ortega & Orgaz-Baz, 2013), with the consequent risk of memory biases. Furthermore, this research has the following specific objectives: it will explore not only (1) the prevalence of exposure, (2) the type of sexual content seen, and the (3) emotional/behavioral reactions, but also and for the first time, other related and relevant variables such as (4) parental filter use, (5) UE as positive or traumatic experience, and at a more in-depth level of analysis will examine (6) emotional and behavioral reactions depending on the type of sexual content.

Our hypothesis are the following: (1) a high percentage of teenagers will have the experience of unwanted online exposure to pornographic contents (UE); (2) the most viewed types of online sex scenes will be naked people, genitals, and erotic/sexual manga; (3) the most frequent reactions after UE will be closing the web page and deleting the Internet history as well as more negative emotions will be observed; (4) a poor parental control is expected; (5) UE will not be a clearly traumatic experience; and (6) different emotional and behavioral reactions will be found depending on the type of sexual content.

Method

Participants

The final sample was made up of 500 teenagers, 256 men (51.2%), and 244 women (48.8%), with an age range of 13–18 years (\(\overline{X}\) = 15.05; SD = 1.05). According to their sexual orientation, 96.8% identified themselves as heterosexual; 2.7% as homosexual; and only 0.5% as bisexual. Our participants were studying in four different high schools in the Spanish Mediterranean coast. The 38.7% were in the third, 32.3% in fourth, only 5% in fifth grade, and 24% were attending a vocational training course. The 89.6% were from Spain, and the rest were immigrants (7.2% were from Romania and 3.2% from 8 different countries, representing each one less than 1%).

Measures

An ad hoc questionnaire was designed to explore the UE to sexually explicit material. This questionnaire was composed of 12 items, using multiple response formats (Likert, yes/no, multiple choice, etcetera), which allowed to explore different factors for the UE. In this research the items used were:

-

1.

Age of the first UE.

-

2.

Parental control: “Do your parents use any type of Internet content control software to protect you from this type of situation?” (Yes/no).

-

3.

UE frequency: “How many times have you involuntarily encountered sexual material on the Internet?” (Never–many times).

-

4.

Type of scenes observed: naked people; straight porn; people showing their genitals; same-sex sexual scenes; erotic or sexual manga; sexual scenes with two or more people; sexual practices involving bondage, discipline, sadism, masochism scenes (BDSM); violent acts; sex with under-age (adolescents/children); scat and piss porn; sexual scenes between people and animals (Multiple choice).

-

5.

The way to unintentionally access sexual material online: while surfing the Internet or another person (known or unknown) presented this content to the adolescent (Multiple choice).

-

6.

Behavioral reactions to the UE: “How did you react when you encountered such material?” Reactions such as rejections or being interested in this material have been registered (e.g., closing immediately the web page, deleting the Internet history, notifying an adult about what have happened, resending those scenes to a friend or peers, keeping seeing porn scenes when they appeared, or having a quick look at them) (Multiple choice).

-

7.

Emotional reactions to the UE: “During such exposure to sexual material, what did you feel?” It has been included the possibility of describing the experience in a negative or positive way (e.g., shame, shock, confusion, disgust, concern, interest, excitation, surprise, anger, fear, guilt, or sadness) (Multiple choice).

-

8.

Traumatic experience: “Has been the experience traumatic for you?” (Yes/no). With this item, it is intended to find out whether the global experience is evaluated as traumatic.

-

9.

Pleasure experience: “Has this experience brought you something positive and as a consequence your sex life is better?” (Yes/no).

Procedure

This study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University from which the research was conducted. The questionnaire was administered in the classroom in pencil format. A psychologist, who was a member of our research group, assured the individual performance of the survey and resolved any possible doubt. Participants were assured at all times that their answers were voluntary and anonymous, thereby guaranteeing their privacy.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were performed with 26 SPSS software. First, descriptive and frequency analyses about sociodemographic were done to explore characteristics of the sample. We also analyzed the type of images and videos observed and the behaviors caused by those visualizations. Finally, multinomial binary logistic regressions were done using positive/traumatic experiences and the behavioral and emotional reactions as dependent variable (DV) and the different types of images/videos and age and gender as independent variable (IV). Those analyses were performed with the intention of discovering the role of each IV in the regression models. For the regression analysis, backward elimination (Wald) was chosen. Nagelkerke coefficient of determination was selected as proportion of variance explained. For all analysis, the significance level used was α = 0.05.

Results

Unexpected Exposure Frequency and Ways of Access

The 88.2% of the participants referred to have unwittingly seen some sexual videos or images. The mean of the first unwanted exposure was 12.06 years (SD = 1.80). Analyzing the last year, 50% of the participants had unexpectedly seen some pornographic material at least three times. Regarding the frequency in which X-rated material has been involuntarily appeared in teenager’s computers/mobile phones, 70% admitted to have seen this type of videos, and more than 20% have seen it very often, which is an indicator of the high amount of pornographic material that can be accidentally visualized on the Internet. Only 11.8% referred that they have never seen that kind of materials on their computers.

Those high frequencies are not out of the ordinary, taking into account that the 85.9% of the families with children did not use a parental control system against pornography, which is an open door for porn publicity or spam advertising.

From those adolescents who have been unwittingly exposed to sexual material online, most of them have accessed this material while surfing the Internet: 60.3% thought it was another type of web page; 44.7% unintentionally clicked on a pop-up or advertisement; and 29.6% mistyped a web page address and accessed sexual material. At about one third of the exposed participants have received e-mails with sexual material (31.3%) or a link to a web page with sexual material (29.3%) from a person they know. To a lesser extent (14.6%), they have received e-mails or links from an unknown person. It should be noted that in moderate but not negligible percentages, adolescents have also received sexual requests through the Internet from both known (17.2%) and unknown (18.7%) people.

Frequency of the Different Kinds of Scenes Observed

In relation to the frequency of the images evaluated in this research, more than 60% of the sample have seen naked people, between 45 and 50% affirmed that they have watched straight porn and genitals on the screen, and finally, more than 38% visualized erotic/sexual manga. Although less frequently, sexual scenes with two or more people (e.g., threesomes or orgies) are common enough (more than 20% of our sample have seen it). Similarly, sexual practices involving bondage, discipline, sadism, masochism, etc. scenes (BDSM) have been visualized by around 15% on the sample. Furthermore, other kinds of scenes, as violent acts, sex with under-age, and scat and piss porn, were not as frequent as the others scenes, even though they have been watched by the 5% of the sample.

Behavioral Reactions Frequencies

Regarding the behavioral reactions when the scenes described in the last paragraph were seen, more than a half of the sample closed immediately the web page, while 36.3% even deleted the Internet history, in order to erase all pornographic marks in the computer/mobile phone. Behaviors as notifying an adult about what have happened or resending those scenes to a friend/peer were less common in our sample (3%). Nonetheless, 14% of the adolescents have kept seeing porn scenes when they appeared, and 24% have also seen those images, although briefly.

Emotional Reaction Frequencies

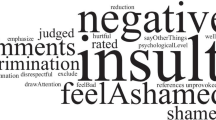

Regarding the participants’ emotional reactions after seeing X-rated material, it should be noted that reactions as shame, shock, and confusion were all of them experimented by around 20% of the sample, indicating how unexpected were those scenes for teenagers. Likewise, cataloging the displayed scenes as disgusting (35%) or concerning (11.5%) was not uncommon in our sample. However, reactions such as experimenting interest or excitation were shown by more than 17% of participants. Similarly, it is remarkable the surprise reaction experienced by almost half of the participants that have seen porn scenes. Finally, reactions as anger, fear, guilt, or sadness were experienced by less than 8% of the teenagers.

Unexpected Exposure and Experienced Consequences

If we look at the percentage of participants who have involuntarily seen pornographic material, the 94.8% do not consider to have lived that experience as traumatic. That is to say, just the 5.2% of our sample has lived that moment such as traumatic.

Likewise, 26% of the participants who have involuntarily seen porn admitted that, as a consequence of this visualization, their sexual life is currently better.

Perceived Experiences Depending on the Type of Visualized Scenes

Different binary logistic regression models were carried out to know what kind of sexual scenes had positive consequences or, conversely, had a negative effect on the participants (Table 1). For the positive experience model, Hosmer and Lemeshow statistic shows that it has a good overall fit (χ2 = 11.671, 8 df, p = 0.167), being a statistically significant model (χ2 = 68.635, 6 df, p < 0.001).

The traumatic experience model is also significant (χ2 = 7.689, 2 df, p = 0.021), with a good overall fit (χ2 = 0.218, 1 df, p = 0.641).

We will carefully explain how to interpret these two models, with the intention that readers could do the same with the other models shown below.

For positive experiences, except sex with teenagers, all variables are significant. Genitals variable has the lower OR, which means that the adolescents who involuntarily visualized genitals have a OR 2.302 times more likely to live that moment as a positive experience, in comparison with teenagers who have not seen that scenes. In other words, these people have a 69.71% (2.302/(2.302 + 1)) more probability of living that moment as a positive time, as long as the other variables of the model are not taken into account. On the other hand, gay porn and gender have a negative coefficient, so the OR will be reinterpreted. The interpretation of these variables is as follows: teenagers who have involuntarily observed gay scenes have a OR 2.667 times lower of living positively that scene; or they have a 72.73% (2.667/(1 + 2.667)) less probability of living that moment positively, if the other variables are constant to zero. Furthermore, if people who visualize gay images or videos are women, there is a 95.28% ((2.667 × 7.576)/(2.667 × 7.576 + 1)) of probability of living that moment as non-positive. In OR, this would be a 20.21 (2.667 × 7.576) times less likely to live that moment as a positive experience, if the other variables are not taken into account.

In the second model, and in relation to traumatic experiences, only zoophilia is a significant variable. If we want to interpret entirely this second model, the following logistic regression equation should be used, taking into account all model variables.

In this equation, we have to introduce all variables in order to avoid forecasting errors. Therefore, the equation for a boy who visualizes a zoophilia scene and, furthermore, with human genitals included in that scene, would be as follows:

Thus, the probability of that adolescent to live traumatically that scene is around 13.3%.

Behavioral Reactions Depending on the Observed Scenes

It was also interesting to know what behavioral reaction each sexual scene raised. For that purpose, logistic regression models were carried out (Table 2). All models presented here have a good overall fit (p > 0.05), being all of them statistically significant (p < 0.05).

In the first model, quick look (QL), all variables except teenagers are significant. The biggest positive OR is for genitals’ variable, which means that teenagers who had visualized those images or videos have a 2.356 times more likely to a quick look, if the constant and other variables in the model are not taken into account. Conversely, gender has a negative coefficient, which means that women have a 62.68% less probability of having a quick look, in comparison with men.

For the look at (LO) model, women have the bigger OR, so they have a 93.6% less probability than men of looking at straight porn, zoophilia images, or under-age sex. On the other hand, zoophilia has the smaller OR, given that under-age sex is not a significant variable. Finally, teenagers observe an 81% more when straight porn is displayed on the computer.

About closing the browser window (CW), women have an 80.83% (4.218/(1 + 4.218)) probability of closing the window if the sexual scenes of the model appear on the screen. Conversely, if BDSM or gay porn appears, it seems that the window is not closed so quickly.

If zoophilia scenes appear in the delete history (DH) model, adolescents try to delete the browser history, concretely a 76.46% (3.248/(1 + 3.248)) more probability to delete it than scenes where do not appear sex with animals. Similarly, browser history is also deleted if naked people scenes have appeared on the computer, although with a low probability (68.4%).

When zoophilia or under-age sex scenes appear, teenagers have more probability of notifying to an adult what have happened, concretely 89% and 87%, respectively. Age variable refers to the first time that adolescents have involuntarily seen some sexual scenes. Its negative coefficient means that, when they see those images or videos for the first time, each year that they get older the OR is 2.364 times less likely to notify an adult, if the other variables are equal to zero.

For the last model, resend (RS), zoophilia and orgy variables are significant. If logistic regression equation is represented for adolescents who have seen zoophilia scenes but they have not seen an orgy, the equation would be as follows:

These teenagers have a 10.1% of probability to resend that material.

Emotional Reactions Depending on the Observed Scenes

Table 3 shows eight different emotions experimented by adolescents when specific sexual scenes are visualized. All models are statistically significant (p < 0.05), with a good overall fit (p > 0.05).

In the first model (concern), naked people and scat/piss porn are significant variables. Adolescents who have visualized scat/piss scenes have an OR 3.317 more likely to be concerned than teenagers that have not seen this scene. Corresponding OR for the naked people variable is 2.093. In this model, gay porn is not a significant variable.

In the disgust model, women have 84.8% more probability than men to feel a great aversion in front of porn scenes. Besides, if that porn scene represents gay sex, women have an OR 1.804 more likely to feel revulsion.

Regarding the surprise model, seeing genitals is surprising for adolescents (66.5%), but not as much as seeing naked people (68.82%). Finally, the gender of the participants is not a significant variable, so there are no significant differences between women and men.

About interest/distraction model, women have 84.7% (5.555/(5.555 + 1)) less probability than men to be interested in the screen. Violence variable is not significant, but if it were, it would reduce an 89.97% the porn scenes interest, if the other variables in the model were zero. BDSM scenes stir up an OR 2.989 times bigger than scenes where this material does not appear. It is worth considering that straight porn is interesting for adolescents, concretely 72% more interesting than scenes were straight porn does not appear, as long as the other variables of the model are equal to zero.

With respect to excitement model, men are who experiment more sexual exaltation (OR = 18.518), especially if genitals, orgies, and straight porn are showed. By contrast, gay porn is not a significant variable (p = 0.059).

The fact of being ashamed is particularly high in women, especially when violent sex scenes are visualized. If we want to know women probability of being ashamed by violent sexual scenes, Eq. 1 should be applied:

Thus, women probability of being ashamed is 70.7%. However, if violent scenes are visualized by men, the equation would be as follows:

In this case, boy’s probability of being ashamed is 43.5%.

If the shock model is analyzed, people who have seen scat/piss porn have an OR 2.947 times more likely to be shocked by that material. Sexual activity with teenagers is not a significant variable in this model. However, women have an OR 2.307 times more likely to be shocked by porn scenes if the other variables are zero. Viewing genitals is also a significant variable in this model.

Finally, only straight porn variable is significant for the confusion model. However, as its coefficient is negative, it means that this type of scenes does not create confusion in adolescents. In OR terms, to visualize heterosexual porn scenes has an OR 2 times less likely to create confusion in teenagers. The other variables (gender, manga, and orgy) are not significant for this model.

Discussion

Our study yielded noteworthy results regarding the current reality of the UE to online pornography in Spanish adolescents. Most of the adolescents assessed have encountered UE to online pornographic material (88.2%). These data are consistent with previous studies that indicated an UE prevalence at around 80% (Castro-Calvo et al., 2015; Flood & Hamilton, 2003; Gil-Juliá et al., 2018, 2019), but in contrast to much more modest data obtained from studies carried out in contexts with more restrictive access to illegal online content than the access found in Europe and Australia (Bernstein et al., 2022; Buljan-Flander et al., 2009; Flood, 2007; Flood & Hamilton, 2003). These frequencies are hardly surprising in light of the poor parental control system against pornography used by families with children in our study and in previous ones (Mitchell et al., 2005; Symons et al., 2017).

These alarming data raise the issue about how family and law should better prevent and tackle this situation in order to protect adolescents. In this regard, some technological, psychoeducational, and legal considerations are provided by previous research (Dombrowski et al., 2004), not to mention the important need to provide more support to parents on how they can implement control strategies (Symons et al., 2017), which may be especially relevant in times of pandemics, such as COVID-19, in which a significant increase in online pornography has been observed (Ballester-Arnal et al., 2020).

Regarding the kind of scenes found on the Internet unexpectedly, naked people, straight porn, and people showing genitals are the most seen. Although to a lesser extent it is also worth considering that scenes of BDSM, sexual violence, and sexual activity with under-age children were included among the content seen by adolescents, to mention some content that would be illegal. These same contents were also found in a previous study with even higher percentages (Sabina et al., 2008).

When it comes to the behavioral reactions derived from the UE, the most frequent reactions after finding the online sexual material were closing immediately the web page and deleting the Internet history, coinciding with previous studies (Castro-Calvo et al., 2015). However, these data also showed some teenager’s interest in sex and pornography given that in noteworthy percentages the adolescents kept seeing porn scenes or saw them for a short while when they appeared. This is in line with research on voluntary exposure to online pornography that indicated sexual online activities among 22–90% of adolescents from diverse European countries and the USA (Ballester-Arnal et al., 2016, 2017b, 2021, 2023; Beyens & Eggermont, 2014; Maas et al., 2017; Ševčíková & Daneback, 2014; Skoog et al., 2009).

As far as emotional reactions are concerned, a greater predominance of more negative emotions was revealed after UE, especially, surprise, disgust, confusion, shock, and shame. A similar tendency to experience negative emotions when facing UE to online pornography was also found in previous studies, particularly among younger children (Flood, 2010). Nevertheless, despite the raising of negative emotional reactions, this experience as a whole not only was not traumatic, but also was even considered as positive. These data are consistent with those obtained by previous research that also found online pornography assessed as positive and with interesting learnings for more than half of the adolescents (Ballester-Arnal et al., 2014), and as a way to improve sexual health and identity, particularly of women, who live in more traditional and restrictive cultures (Giménez-García et al., 2020). Likewise, in relation to the positive outcomes of online pornography, it would be interesting to consider whether the positive evaluation of some sexual content could generally be linked to content of low intensity, which in addition to reveal the lack of an effective sexual education, would not be expected to cause emotional or other damages in adolescents, even when it comes to UE.

Analyzing in-depth the experiences and reactions cited above allowed us to find significant results depending on the type of scenes. It is worth considering that no previous studies about this issue have been found in the reviewed literature, which has included studies carried out worldwide.

The multinomial binary logistic regressions showed that the visualization of scenes with genitals, orgies, and zoophilia is lived as a positive experience. Moreover, gay porn and gender were also significant but with a negative coefficient. Thus, gay scenes and being woman increased the probability of living that experience as non-positive. These results may be explained by the higher percentage of heterosexual participants in our study.

Regarding perceiving the experience as traumatic, scenes with zoophilia content had also higher odds. These data are consistent with other research that found sexual activity with people and animals’ scenes having a high impact for adolescents (González-Ortega & Orgaz-Baz, 2013).

Regarding the behavioral reactions after UE, our study also provides noteworthy results depending on the observed scenes. To sum up the information related to behavioral reactions, some scenes seemed to be more associated with behavioral reactions of rejection, that is, to close the window, delete the Internet history, and notify to an adult. In this regard, viewing naked people had higher odds of deleting the history and closing the window. It is also noteworthy the role of BDSM scenes which were associated with closing the window. Likewise, under-age sex had higher odds of notifying to an adult. On the other hand, straight porn scenes were associated with behaviors of interest; that is, this kind of scene had higher odds of having a quick look and looking at the scene. Regarding sex with animal’s scenes, the results were controversial. These scenes were associated with both rejection and interest behavioral reactions. That is because this material was associated with both positive and traumatic experiences as it has been explained a few lines above. Although in both models this variable was significant, the OR in the traumatic experience model was higher than in the positive model. Thus, it could be concluded that visualizing sex with animals had a more traumatic than a positive effect. Other two important variables when considering the behavioral reactions are the gender and the age. Being a woman was more associated with behaviors of rejection (e.g., closing the window), as well as this variable had lower odds of looking at these materials.

Considering these results, the gender seems to be a relevant variable. It influences the living of the experience as positive or traumatic as well as the behavioral reaction derived from the viewing of porn unexpectedly, being the women who more frequently show rejection behavioral reactions and experience the UE as traumatic. These findings are in line with those obtained in previous studies that explored the role of gender (Castro-Calvo el at., 2015; Livingstone et al., 2011; Martellozzo et al., 2017). These data could also be influenced by the fact that the pornography viewed may have degrading overtones towards women — an aspect studied so far only in men (Skorska et al., 2018) — specially, heterosexual pornography, which may explain that many women reject this type of pornography regardless of their orientation (Giménez-García et al., 2021). These data are of great value insofar as can be reflected that this issue may not be about female prudishness, but rather empathy towards those affected by abuse, which their male peers should also feel to a greater extent than the results show. Again, this would also evidence a lack of effective education in the affective and sexual sphere.

On the other hand, the age of the adolescents seemed to be more associated with behavioral reactions of interest such as having a quick look. In this same way, getting older was associated with lower likelihood of notifying it to an adult. This is another important variable to the extent that is showing the increasing interest in sexual online activities during adolescence and youth also stated by previous authors (Ballester-Arnal et al., 2016; Maes & Vandenbosch, 2022).

As far as emotional reactions are concerned, naked people and piss/scat porn (pornography involving urine and feces) had higher odds of experiencing concern. Gay porn scenes and gender (being a woman) were associated with disgust. Viewing naked people was also associated with feelings of surprise, and the same is true for viewing genitals. Regarding shame, viewing violence scenes and being woman had higher odds of experiencing this emotional reaction. When it comes to experiencing shock, viewing genitals and piss/scat porn had higher odds. Likewise, the gender (being a woman) increased the likelihood of shock. With regard to more positive emotional reactions, BDSM and straight porn showed higher odds of experiencing interest and distraction. Again, straight porn, as well as genitals, and orgy scenes were associated with excitement. It is also worth considering that gender (being a woman) had lower odds of experiencing positive emotional reactions, both interest and excitement.

Once again, the gender raised as a key variable in the reactions derived from UE but in this case in the emotions that online pornography aroused in adolescents. These data are consistent with those studies that showed higher likelihood of experiencing disgust, embarrassment, shame, and worry in women and more positive emotions in men (González-Ortega & Orgaz-Baz, 2013; Sabina et al., 2008).

It is important to bear in mind that we found no studies that explore the role of the content seen in the different experiences and reactions derived from the UE to online pornography, making it difficult to compare our results, which in turn enhances the value of this study given the diverse consequences and impact that viewing different types of sexual content online may have.

Finally, it should be noted that the results obtained are noteworthy and open a path to more in-depth research into UE, as well as the detection of deficiencies in the affective-sexual education of adolescents and young people.

These findings should be considered in light of some limitations. First, the study was conducted with participants living in Spain although some of them came from other countries and cultural differences may have affected the findings. Second, despite guaranteeing participants complete confidentiality and anonymity, it is difficult to rule out that bias due to social desirability could have influenced certain responses, especially taking into account that this research focused on a complex topic and some adolescents might have found it difficult to share their experiences. Third, the information collected is retrospective, and we know that reporting what is remembered when asked about past experiences is always subject to certain distortions and memory bias may appear remembering only that information with the most notable impact or the greatest intensity. However, we ask adolescents — unlike other studies that ask adults — so recall biases may be minimal because we are asking them about recent experiences over time. At the same time, we assume the risk that they may not be telling the truth given that parental control is rather scarce, and they could be looking for this material and not admit it.

These limitations notwithstanding, the current study demonstrates strengths in the findings and contributes significantly to the knowledge of UE to online pornography in adolescents. Particularly, this is the first study in Spain to ask adolescents directly about this issue. It provides greater information about the role played by different variables such as the type of sexual content seen and the gender in the diverse reactions and experiences derived from the exposure to pornography unexpectedly. This topic should be included in affective-sexual education and prevention programs at early ages, so that children/adolescents are already trained in healthy sexuality when facing this type of content for the first time. These programs, adjusted to the reality of our adolescents, will try to minimize the negative impact that UE may have on their psychosexual development.

Likewise, future research focusing on the positive experience derived from the exposure to online sexual content is required, which may shed greater light on this important topic, as well as more information on the possible positive or negative long-term effects of this UE. Research has been mainly focused on whether or not the exposure to these materials is traumatic in the short term. Nevertheless, more data on possible differences in the medium and long term are needed in relation to how those people who have been exposed (or not) early to this type of materials behave or experience their sexuality.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Aisbett, K. (2001). The Internet at home: A report on Internet use in the home. Australian Broadcasting Authority.

Ballester-Arnal, R., Castro-Calvo, J., García-Barba, M., Ruiz-Palomino, E., & Gil-Llario, M. D. (2021). Problematic and non-problematic engagement in online sexual activities across the lifespan. Computers in Human Behavior, 120, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106774

Ballester-Arnal, R., Castro-Calvo, J., Gil-Llario, M. D., & Gil-Juliá, B. (2017a). Cybersex addiction: A study on Spanish college students. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 43(6), 567–585. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2016.1208700

Ballester-Arnal, R., Castro-Calvo, J., Gil-Llario, M. D., Giménez-García, C., & Ceccato, R. (2014). Exposición involuntaria: Impacto en usuarios y no usuarios de cibersexo. [Unwanted exposure: Impact on cybersex users and non-users]. International Journal of Developmental and Educational Psychology, 1, 517–526.

Ballester-Arnal, R., García-Barba, M., Castro-Calvo, J., Giménez-García, C., & Gil-Llario, M. D. (2023). Pornography consumption in people of different age groups: An analysis based on gender, contents, and consequences. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 20, 766–779. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-022-00720-z

Ballester-Arnal, R., Gil-Llario, M. D., Giménez-García, C., Castro-Calvo, J., & Cardenas-López, G. (2017b). Sexuality in the Internet era: Expressions of Hispanic adolescent and young people. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 24(3), 140–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/10720162.2017.1329041

Ballester-Arnal, R., Giménez-García, C., Gil-Llario, M. D., & Castro-Calvo, J. (2016). Cybersex in the “Net generation”: Online sexual activities among Spanish adolescents. Computers in Human Behavior, 57, 261–266.

Ballester-Arnal, R., Nebot-García, J. E., Ruiz-Palomino, E., Giménez-García, C., & Gil-Llario, M. D. (2020). “INSIDE” project on sexual health in Spain: Sexual life during the lockdown caused by COVID-19. Sexuality Research and Social Policy. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-020-00506-1

Bandura, A. (2002). Social cognitive theory of mass communication. In J. Bryant & D. Zillmann (Eds.), Media effects: Advance in theory and research (pp. 121–153). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Bandura, A. (2009). Social cognitive theory of mass communication. In J. Bryant & M.B. Oliver (Eds.), Media effects. Advances in theory and research (pp. 94–124). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Bernstein, S., Warburton, W., Bussey, K., & Sweller, N. (2022). Mind the gap: Internet pornography exposure, influence and problematic viewing amongst emerging adults. Sexuality Research and Social Policy. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-022-00698-8

Best, P., Manktelow, R., & Taylor, B. (2014). Online communication, social media and adolescent wellbeing: A systematic narrative review. Children and Youth Services Review, 41, 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.03.001

Beyens, I., & Eggermont, S. (2014). Prevalence and predictors of text-based and visually explicit cybersex among adolescents. Young, 22, 43–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/0973258613512923

Brown, J. D., & Bobkowski, P. S. (2011). Older and newer media: Patterns of use and effects on adolescents’ health and well-being. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21(1), 95–113. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00717.x

Bryant, C. (2009). Adolescence, pornography and harm. Trends & Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice, 368, 1–6.

Buljan-Flander, G., Cosic, I., & Profaca, B. (2009). Exposure of children to sexual content on the Internet in Croatia. Child Abuse & Neglect, 33, 849–856.

Castro-Calvo, J., Gómez-Martínez, S., Gil-Juliá, B., Giménez-García, C., & Ballester-Arnal, R. (2015). Jóvenes y sexo en la red. Reacción ante la exposición involuntaria a material sexual. [Young people and sex on the net. Reaction to involuntary exposure to sexual material]. Agora Salut, 1, 187–198.

Childwise. (2017). Monitor report 2017: Children’s media use and purchasing. Retrieved December 10, 2022, from www.childwise.co.uk/reports.html#monitorreport

Collins, R. L., Strasburger, V. C., Brown, J. D., Donnerstein, E., Lenhart, A., & Ward, L. M. (2017). Sexual media and childhood well-being and health. Pediatrics, 140, S162–S166. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1758X

Delmonico, D. L., & Griffin, E. J. (2008). Cybersex and the E-teen: What marriage and family therapists should know. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 34(4), 431–444. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2008.00086.x

DeMarco, J. N., Cheevers, C., Davidson, J., Bogaerts, S., Pace, U., Aiken, M., Caretti, V., Schimmenti, A., & Bifulco, A. (2017). Digital dangers and cyber-victimisation: A study of European adolescent online risky behaviour for sexual exploitation. Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 14(1), 104–112.

Dombrowski, S. C., LeMasney, J. W., Ahia, C. E., & Dickson, S. A. (2004). Protecting children from online sexual predators: Technological, psychoeducational, and legal considerations. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 35(1), 65–73. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.35.1.65

Ey, L.-A., & Cupit, C. G. (2011). Exploring young children’s understanding of risks associated with Internet usage and their concepts of management strategies. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 9, 53–65.

Finkelhor, D., Mitchell, K. J., & Wolak, J. (2000). Online victimization: A report on the nation’s youth. National Center for Missing & Exploited Children Bulletin (#6-00-020).

Flood, M. (2007). Exposure to pornography among youth in Australia. Journal of Sociology, 43(1), 45–60.

Flood, M. (2010). The harms of pornography exposure among children and young people. Child Abuse Review, 18, 384–400.

Flood, M., & Hamilton, C. (2003). Youth and pornography in Australia: Evidence on the extent of exposure and likely effects. The Australia Institute.

Foubert, J. D., Blanchard, W., Houston, M., & Williams, R. R. (2019). Pornography and sexual violence. In: W. O'Donohue, & P. Schew (Eds.), Handbook of Sexual Assault and Sexual Assault Prevention (pp. 109–127). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-23645-8_7

Gil-Juliá, B., Castro-Calvo, J., Martínez-Gómez, N., Cervigón-Carrasco, V., & Gil-Llario, M. D. (2019). Reacción emocional ante la exposición involuntaria a cibersexo en adolescentes: Factores moduladores. [Emotional reaction to involuntary exposure to cybersex in adolescents: Modulating factors]. International Journal of Developmental and Educational Psychology, 1, 413–422.

Gil-Juliá, B., Castro-Calvo, J., Ruiz-Palomino, E., García-Barba, M., & Ballester-Arnal, R. (2018). Consecuencias de la exposición involuntaria a material sexual en adolescentes. [Consequences of unintentional exposure to sexual material in adolescents]. International Journal of Developmental and Educational Psychology, 1, 33–44.

Giménez-García, C., Nebot-García, J. E., Ruiz-Palomino, E., García-Barba, M., & Ballester-Arnal, R. (2021). Spanish women and pornography based on different sexual orientation: An analysis of consumption, arousal, and discomfort by sexual orientation and age. Sexuality Research and Social Policy. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-021-00617-3

Giménez-García, C., Ruiz-Palomino, E., Gil-Llario, M. D., & Ballester-Arnal, R. (2020). Online sexual activities in Hispanic women: A chance for non-heterosexual women? Journal of Psychopathology and Clinical Psychology, 25(1), 41–47. https://doi.org/10.5944/rppc.25399

González-Ortega, E., & Orgaz-Baz, B. (2013). Minors’ exposure to online pornography: Prevalence, motivations, contents and effects. Anales De Psicología, 29, 319–327.

Hardy, S. A., Steelman, M. A., Coyne, S. M., & Ridge, R. D. (2013). Adolescent religiousness as a protective factor against pornography use. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 34, 131–139.

Harris, R. J., & Christina, L. S. (2002). Effects of sex in media. In J. Bryant & D. Zillmann (Eds.), Media Effects Advance in Theory and Research (pp. 43–67). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Hornor, G. (2020). Child and adolescent pornography exposure. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 34(2), 191–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedhc.2019.10.001

Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). (2020). Encuesta sobre Equipamiento y Uso de Tecnologías de la Información y Comunicación en los hogares. Retrieved December 7, 2022, from http://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/es/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_C&cid=1254736176741&menu=ultiDatos&idp=1254735976608

Jones, L. M., Mitchell, K. J., & Finkelhor, D. (2012). Trends in youth Internet victimization: Findings from three youth Internet safety surveys 2000–2010. Journal of Adolescent Health, 50, 179–186.

Kloess, J. A., Beech, A. R., & Harkins, L. (2014). Online child sexual exploitation. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 15, 126–139.

Livingstone, S., Haddon, L., Görzig, A., & Ólafsson, K. (2011). Risks and safety on the internet: The perspective of European children. Full Findings. EU Kids Online.

Maas, M. K., Bray, B. C., & Noll, J. G. (2017). A latent class analysis of online sexual experiences and offline sexual behaviors among female adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 28(3), 731–747. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12364

Madigan, S., Villani, V., Azzopardi, C., Laut, D., Smith, T., Temple, J. R., Browne, D., & Dimitropoulos, G. (2018). The prevalence of unwanted online sexual exposure and solicitation among youth: A meta-analysis. Journal of Adolescent Health, 63, 133–141.

Maes, C., & Vandenbosch, L. (2022). Adolescents’ use of sexually explicit Internet material over the course of 2019–2020 in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic: A three-wave panel study. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51, 105–121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-021-02122-5

Martellozzo, E., Monaghan, A., Adler, J. R., Davidson, J., Leyva, R., & Horvath, M. A. H. (2017). I wasn’t sure it was normal to watch it. A quantitative and qualitative examination of the impact of online pornography on the values, attitudes, beliefs and behaviours of children and young people. Middlesex University, NSPCC, OCC. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.3382393

Mifsud, E. (2009). Monográfico: Control parental-Uso de internet: riesgos y beneficios. Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte. Retrieved December 10, 2022, from http://recursostic.educacion.es/observatorio/web/eu/software/software-general/909-monografico-control-parental?start=1

Mitchell, K. J., Finkelhor, D., & Wolak, J. (2003). The exposure of youth to unwanted sexual material on the Internet: A national survey of risk, impact, and prevention. Youth & Society, 34, 330–358.

Mitchell, K. J., Finkelhor, D., & Wolak, J. (2005). Protecting youth online: Family use of filtering and blocking software. Child Abuse & Neglect, 29, 753–765.

Mitchell, K. J., Jones, L., Finkelhor, D., & Wolak, J. (2014). Trends in unwanted online experiences and sexting: Final report. Crimes Against Children Research Center. Retrieved December 7, 2022, from http://www.unh.edu/ccrc/pdf/Full%20Trends%20Report%20Feb%202014%20with%20tables.pdf

Mitchell, K. J., Wolak, J., & Finkelhor, D. (2007). Trends in youth reports of sexual solicitations, harassment and unwanted exposure to pornography on the Internet. Journal of Adolescent Health, 40, 116–126.

Paat, Y.-F., & Markham, C. (2021). Digital crime, trauma, and abuse: Internet safety and cyber risks for adolescents and emerging adults in the 21st century. Social Work in Mental Health, 19(1), 18–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332985.2020.1845281

Peter, J., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2008). Adolescents’ exposure to sexually explicit Internet material and sexual preoccupancy: A three-wave panel study. Media Psychology, 11(2), 207–234.

Peter, J., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2016). Adolescents and pornography: A review of 20 years of research. Journal of Sex Research, 53(4–5), 509–531. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2016.1143441

Rissel, C., Richters, J., de Visser, R. O., McKee, A., Yeung, A., & Caruana, T. (2017). A profile of pornography users in Australia: Findings from the second Australian study of health and relationships. Journal of Sex Research, 54, 227–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2016.1191597

Rothman, E. F., Daley, N., & Adler, J. (2020). A pornography literacy program for adolescents. American Journal of Public Health, 110, 154–156. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2019.305468

Sabina, C., Wolak, J., & Finkelhor, D. (2008). The nature and dynamics of internet pornography exposure for youth. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 11(6), 1–3.

Ševčíková, A., & Daneback, K. (2014). Online pornography use in adolescence: Age and gender differences. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 11, 674–686. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2014.926808

Ševčíková, A., Simon, L., Daneback, K., & Kvapilík, T. (2015). Bothersome exposure to online sexual content among adolescent girls. Youth & Society, 47(4), 486–501.

Skoog, T., Stattin, H., & Kerr, M. (2009). The role of pubertal timing in what adolescent boys do online. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 19(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00578.x

Skorska, M. N., Hodson, G., & Hoffarth, M. R. (2018). Experimental effects of degrading versus erotic pornography exposure in men on reactions toward women (objectification, sexism, discrimination). The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 27(3), 261–276. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjhs.2018-0001

Symons, K., Ponnet, K., Walrave, M., & Heirman, W. (2017). A qualitative study into parental mediation of adolescents’ internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 73, 423–432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.04.004

Ward, L. M. (2016). Media and sexualization: State of empirical research, 1995–2015. Journal of Sex Research, 53(4–5), 560–577. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2016.1142496

Wolak, J., Mitchell, K., & Finkelhor, D. (2006). Online victimization of youth: Five years later. National Center for Missing & Exploited Children Bulletin #07-06-025. Retrieved December 10, 2022, from https://www.unh.edu/ccrc/sites/default/files/media/2022-03/online-victimization-of-youth-five-years-later.pdf

Wolak, J., Mitchell, K., & Finkelhor, D. (2007). Unwanted and wanted exposure to online pornography in a national sample of youth Internet users. Pediatrics, 119(2), 247–257.

Ybarra, M. L., & Mitchell, K. J. (2004). Youth engaging in online harassment: Associations with caregiver-child relationships, internet use, and personal characteristics. Journal of Adolescence, 27(3), 319–336.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their thanks to A. Schmidt for performing language revision.

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. This work was supported by the project P1.1B2015-82, Jaume I University of Castellón.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.B.A. and M.D.G.L. contributed to the study design, obtaining funding, and study supervision. R.B.A., M.D.G.L., B.G.J., M.E.M., and C.G.G. participated in recruiting participants, collecting data, analysis/interpretation of data, and/or writing of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

The study procedures were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The Institutional Review Board of the Jaume I University approved the study.

Consent to Participate

All participants in the research were informed about the objectives of the study as well as about the anonymity and confidentiality of the responses. After being informed and having resolved any doubts, informed consent was obtained so that the participants could take part in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ballester-Arnal, R., Gil-Julia, B., Elipe-Miravet, M. et al. Experiences and Psychological Impact Derived from Unwanted Exposure to Online Pornography in Spanish Adolescents. Sex Res Soc Policy (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-023-00888-y

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-023-00888-y