Abstract

During the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, domestic violence came to be understood as a national emergency. In this paper, we ask how and why domestic violence was constructed as a crisis specific to the pandemic. Drawing from newspaper data, we show that the domestic violence victim came to embody the violation of gendered boundaries between “public” and “private” spheres. Representations of domestic violence centered on violence spilling over the boundaries of the home, infecting the home, or the home imploding. While theorists of crisis have focused on the central role of temporality in crisis construction, and especially the performative invocation of “new time,” we argue that crisis rhetoric often relies on anxiety about the transgression of spatial boundaries. Our spatial approach to crisis has two components. First, we argue that crisis framings often invoke the idea that seemingly distinct arenas of social life are becoming disorganized or blurred. And second, because thresholds between social spaces are coded as sacred during crisis, this spatial reordering is rendered dangerous, resulting in calls to resecure boundaries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

As historians have shown, fears about family violence in the U.S. have long been fixated on the “cultural image of home life as a harmonious, loving, and supportive environment” (Gordon, 1988:2).

According to the Alliance for Audited Media, a digital edition “… is defined as a product distributed via electronic/digital means that maintains the basic identity of the host publication either by maintain the same name/log or by identifying itself as ‘an edition of ________,’ but contains different editorial and/or advertising content.” In rare cases, an identical article was produced as a digital edition and print edition with different publication dates. For these cases, the article with the earlier publication date is included and the later publication date is excluded. The difference in dates was under 5 days.

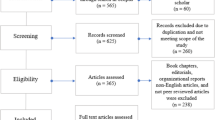

We excluded articles that did not have any correlation between group one and two words, but we included articles in which groups one and two had a relationship within the article. We followed this method for other niche articles in which words from group two were unrelated to a case mentioning words in group one, but we were liberal in including articles to capture an initial, broad collection of data.

In the academic and policy literatures, experts questioned the validity of quantitative data about domestic violence, especially police data, and expressed uncertainty about whether domestic violence was increasing and if it was, for whom and for how long. This is, in part, because what constitutes violence is itself contested (Merry, 2016) and it is further unclear if domestic violence statistics are actually capturing victimization rates, help-seeking behaviors, or third-party reporting trends (Piquero et al., 2021).

It matters that studies based on administrative data such as police calls were most commonly cited in newspapers during the first few months of the pandemic. Most research reports using police data reported an increase in domestic violence prevalence when compared to pre-pandemic times ( Piquero et al., 2021; Mendie et al., 2022; Boserup et al., 2020) with some studies indicating increases anywhere from 7.5% (Leslie & Wilson, 2020) to 22% (McLay, 2022). Most findings that reference hotline contact volume, on the other hand, indicate that domestic violence prevalence did increase during the pandemic, but only after shelter-in-place orders were lifted (Leigh et al., 2022; Wood et al., 2020; NNEDV, 2021). The National Domestic Violence Hotline (2022) reported the highest contact volume in the organization’s history in February 2022. Only studies using police data found evidence for domestic violence spiking during the pandemic’s “initial shock” (Henke & Hsu, 2022) or during the first months of the pandemic (Leslie & Wilson, 2020; Piquero et al., 2020).

Most survey data that measured survivors’ experiences during the pandemic found that domestic violence increased or worsened among those experiencing other forms of social marginality before and during the pandemic. These studies indicated that domestic violence during COVID was more prevalent or more severe among: those subjected to unemployment and pandemic-related job loss (Davis et al., 2021; Peitzmeier et al., 2022; Wake & Kandula, 2022; McNeil et al., 2022) and economic, housing, and food instability (Peitzmeier et al., 2022; McNeil et al., 2022); essential workers (Peitzmeier et al., 2022); people who stayed home all day (Henke & Hsu, 2022; Hsu & Henke, 2020), or were housewives or married (Wake & Kandula, 2022); those who were pregnant (Peitzmeier et al., 2022; Bueso-Izquierdo et al., 2022), lived with children (UN Women & Women Count, 2021), or had a toddler (Peitzmeier et al., 2022); people with mental illness and drug abuse habits (Wake & Kandula, 2022; McNeil et al., 2022) or impacted by the COVID-19 virus (Davis et al., 2021; Peitzmeier et al., 2022; McNeil et al., 2022); and LGBTQ + people (Peitzmeier et al., 2022; McCool-Meyers et al., 2022).

A survey conducted in Michigan during the first several months of the pandemic, however, shows that rates of domestic violence did not change, but severity of existing abuse increased for marginalized people (Peitzmeier et al., 2022).

Since poor and working-class women and women of color (arguably the most chronically burned-out parental figures) have historically engaged in “public” reproductive labor, this proposed solution continues to rely on these women’s labor to maintain a lived sense of the public-private divide as real for middle-class families (Collins, 1990; Parreñas, 2000; Duffy, 2007). Indeed, when it comes to poor and/or racialized families’ “private sphere” crises, dissolving and disregarding the boundary between public and private life is often seen as protective (Roberts, 2022). For example, these families’ private lives are subjected to sometimes chronic surveillance by state actors, such as Child Protective Service officers (Smith & Roane, 2023). As such, the public-private divide is a classed and racialized ideology that can only be lived as separate by some (see New York Times, December 29, 2020).

References

Berlant, L. (2007). Slow death (sovereignty, obesity, lateral agency). Critical Inquiry, 33(4), 754–780.

Bettinger-Lopez, C., & Bro, A. (2020). A double pandemic: Domestic Violence in the age of COVID-19. Council on Foreign Affairs. https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/double-pandemic-domestic-violence-age-covid-19.

Boserup, B., McKenney, M., & Elkbuli, A. (2020). Alarming trends in US Domestic Violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 38(12), 2753–2755.

Braun, R. (2022). Bloodlines: National Border crossings and Antisemitism in Weimar Germany. American Sociological Review, 87(2), 202–236.

Bueso-Izquierdo, N., Daughtery, J. C., Puente, A. E., & Caparros-Gonzalez, R. A. (2022). Intimate partner Violence and pregnancy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Gender Studies, 31(5), 573–583.

Collins, P. H. (1990). Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. Routledge.

Davis, M., Gilbar, O., & Padilla-Medina, D. M. (2021). Intimate Partner Violence victimization and perpetration among U.S. adults during the Earliest Stage of the COVID-19 pandemic. Violence and Victims 36(5).

Decoteau, C. L. (2023). Emergency: COVID-19 and the Uneven Valuation of Life. American Sociological Association Coser Lecture. Philadelphia, PA. 20 August 2023.

Douglas, M. (1966). Purity and Danger: An analysis of concepts of Pollution and Taboo. Routledge.

Dow, D. M. (2019). Mothering while black: Boundaries and burdens of Middle-Class parenthood. University of California Press.

Doyle, K., Durrence, A., & Passi, S. (2020). Survivors Know Best: How to Disrupt Intimate Partner Violence during COVID-19 and Beyond. FreeFrom. https://www.freefrom.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Survivors-Know-Best.pdf.

Duffy, M. (2007). Doing the dirty work: Gender, race, and Reproductive Labor in historical perspective. Gender & Society, 21(3), 313–336.

Evans, M. L., Lindauer, M., & Farrell, M. E. (2020). A pandemic within a pandemic — intimate Partner Violence during Covid-19. New England Journal of Medicine, 383, 2302–2304.

Fox, G. L., Benson, M. D., DeMaris, A. A., & Van Wyk, J. (2002). Economic distress and intimate Violence: Testing family stress and resources theories. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64(3), 793–807.

Glenn, E. N. (1999). The Social Construction and institutionalization of gender and race. In J. Lorber, & B. B. Hess (Eds.), Revisioning gender (pp. 3–43). Myra Marx Ferree.

Gordon, L. (1988). Heroes of their own lives: The politics and History of Family Violence. University of Illinois Press.

Hagen, R., & Elliott, R. (2021). Disasters, continuity, and the pathological normal. Sociologica, 15(1), 1–9.

Hall, S., Critcher, C., Jefferson, T., Clarke, J., & Roberts, B. (1978). [2017] policing the Crisis: Mugging, the state and law and order. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Heilman, M., & Calarco, J. (2022). Home is where it happens: A visual essay on pandemic parenting for employed mothers. Visual Studies: 1–4.

Henke, A., & Hsu, L. (2022). COVID-19 and Domestic Violence: Economics or isolation? Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 43, 296–309.

Hsu, L., & Henke, A. (2020). COVID-19, staying at home, and Domestic Violence. Review of Economics of the Household, 19(2021), 145–155.

Leigh, J. K., Peña, L. D., Anurudran, A., & Pai, A. (2022). ‘Are you safe to talk?’: Perspectives of Service providers on experiences of Domestic Violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Family Violence.

Leslie, E., & Wilson, R. (2020). Sheltering in place and domestic violence: Evidence from calls for service during COVID-19. Journal of Public Economics. 189(2020): 104241.

MacKinnon, C. A. (1989). Toward a Feminist Theory of the state. Harvard University Press.

Mallett, S. (2004). Understanding home: A critical review of the literature. The Sociological Review, 52(1), 62–89.

McCool-Myers, M., Kozlowski, D., Jean, V., Cordes, S., Gold, H., & Goedken, P. (2022). The COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on sexual and reproductive health in Georgia, USA: An exploration of behaviors, contraceptive care, and partner abuse. Contraception 113(2022): 30–36.

McLay, M. M. (2022). When ‘Shelter-in-place’ isn’t Shelter that’s safe: A Rapid Analysis of Domestic Violence Case differences during the COVID-19 pandemic and stay-at-home orders. Journal of Family Violence, 37, 861–870.

McNeil, A., Hicks, L., Yalcinoz-Ucan, B., & Browne, D. T. (2022). Prevalence & correlates of intimate Partner Violence during COVID-19: A Rapid Review. Journal of Family Violence.

Mendie, E., Raufu, A., Ben Edet, E., & Famakin-Johnson, O. (2022). Nowhere to Run. Impact of Family Violence Incidents during COVID-19 Lockdown in Texas. Journal of Family Strengths 21(1): Art. 3.

Merry, S. E. (2016). The seductions of quantification: Measuring Human rights, gender Violence, and sex trafficking. The University of Chicago Press.

Mohler, G., Bertozzi, A. L., Carter, J., Short, M. B., Sledge, D., Tita, G. E., Uchida, C. D., & Brantingham, P. J. (2020). Impact of social distancing during COVID-19 pandemic on crime in Los Angeles and Indianapolis. Journal of Criminal Justice 68 (101692).

Nash, J. C. (2021). Birthing black mothers. Duke University Press.

National Domestic Violence Hotline [NDVH] (2020). COVID-19 Special Report. https://www.thehotline.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2020/06/2005-TheHotline-COVID19-report_final.pdf.

National Domestic Violence Hotline [NDVH] (2022). National Domestic Violence Hotline Welcomes President’s Proposed Budget. https://www.thehotline.org/news/national-domestic-violence-hotline-welcomes-presidents-proposed-budget/.

National Network to End Domestic Violence [NNEDV] (2021). Tech Abuse in the Pandemic and Beyond: Reflections from the Field. https://www.ojp.gov/library/publications/tech-abuse-pandemic-beyond-reflections field#:~:text = Tech%20Abuse%20in%20the%20Pandemic%20%26%20Beyond%3A%20Reflections%20from%20the%20Field,-NCJ%20Number&text = This%20report%20presents%20findings%20and,during%20the.

Parreñas, R. S. (2000). Migrant Filipina Domestic Workers and the International Division of Reproductive Labor. Gender & Society, 14(4), 560–580.

Pateman, C. (1983). Feminist critiques of the Public/Private dichotomy. In S. I. Benn, & G. F. Gaus (Eds.), Public and Private in Social Life (pp. 281–303). St. Martin’s Press.

Peitzmeier, S. M., Fedina, L., Ashwell, L., Herrenkohl, T. I., & Tolman, R. (2022). Increases in intimate Partner Violence during COVID-19: Prevalence and correlates. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 0(0), 1–31.

Piquero, A. R., Riddell, J. R., Bishopp, S. A., Narvey, C., Reid, J. A., & Piquero, N. L. (2020). Staying home, staying safe? A short-term analysis of COVID-19 on Dallas Domestic Violence. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 45, 601–635.

Piquero, A. R., Jennings, W. G., Jemison, E., Kaukinen, C., & Knaul, F. M. (2021). Domestic Violence during the COVID-19 pandemic - evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Criminal Justice, 74, 101806.

Polletta, F., & Chen, P. C. B. (2013). Gender and public talk: Accounting for women’s variable participation in the public sphere. Sociological Theory, 31(4), 291–317.

Povinelli, E. A. (2011). Economies of Abandonment: Social belonging and endurance in late Liberalism. Duke University Press.

Reed, I. A. (2015). Deep Culture in Action: Resignification, synecdoche, and metanarrative in the moral panic of the Salem Witch trials. Theory and Society, 44(1), 65–94.

Reed, I. A. (2016). Between Structural Breakdown and Crisis Action: Interpretation in the Whiskey Rebellion and the Salem Witch trials. Critical Historical Studies, 3(1), 27–64.

Richie, B. E. (2012). Arrested justice: Black women, Violence, and America’s prison nation. New York University Press.

Ritchie, A. J. (2017). Invisible no more: Police Violence against black women and women of color. Beacon press.

Roberts, D. (2022). Torn apart: How the child welfare system destroys black families—and how abolition can build a safer world. Basic Books.

Roitman, J. (2013). Anti-crisis. Duke University Press.

Saguy, A. C. (2013). What’s wrong with Fat? Oxford University Press.

Savelsberg, J. (2015). Representing Mass Violence: Conflicting responses to Human Rights Violations in Darfur. University of California Press.

Sendroiu, I. (2022a). From reductive to generative crisis: Businesspeople using polysemous justifications to make sense of COVID-19. American Journal of Cultural Sociology, 11(1), 50–76.

Sendroiu, I. (2022b). All the old illusions: On guessing at being in Crisis. Sociological Theory, 40(4), 297–321.

Sendroiu, I. (2023). Events and crises: Toward a conceptual clarification. American Behavioral Scientist 1–28.

Sewell, W. H. (1996). Historical events as transformations of structures: Inventing revolution at the Bastille. Theory & Society, 25(6), 841–881.

Shariati, A., & Guerette, R. T. (2022). Findings from a natural experiment on the impact of covid-19 residential quarantines on Domestic Violence patterns in New Orleans. Journal of Family Violence 1–12.

Smith, D. Y., & Roane, A. (2023). Child removal fears and black mothers’ medical decision-making. Contexts, 22(1), 18–23.

Sontag, S. (1977). Illness as Metaphor. Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

Strings, S. (2015). Obese black women as social dead weight: Reinventing the diseased black woman. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 41(1), 107–130.

Strings, S. (2019). Fearing the black body: The racial origins of fat phobia. New York University Press.

Swidler, A. (1986). Culture in action: Symbols and strategies. American Sociological Review, 51(2), 273–286.

Tavory, I., & Wagner-Pacifici, R. (2022). Climate change as an event. Poetics, 93, 101600.

Treichler, P. (1987). AIDS, Homophobia, and Biomedical Discourse: An epidemic of signification. Cultural Studies, 1(3), 263–305.

United Nations Women [UN Women] and Women Count (2021). Measuring the Shadow Pandemic: Violence Against Women During COVID-19https://data.unwomen.org/publications/vaw-rga.

Wagner-Pacifici, R. (2017). What is an event? University of Chicago Press.

Wagner-Pacifici, R. (2021). “What is an Event and Are We in One?“ Sociologica 15(1): 11–20.

Wake, A. D., & Kandula, U. R. (2022). The global prevalence and its associated factors toward Domestic Violence against women and children during COVID-19 pandemic—‘The shadow pandemic’: A review of cross-sectional studies. Women’s Health, 18, 1–13.

Walby, S. (2021). The COVID Pandemic and Social Theory: Social Democracy and public health in the crisis. European Journal of Social Theory, 24(1), 22–43.

Wood, L., Schrag, R. V., Baumler, E., Hairston, D., Guillot-Wright, S., Torres, E., & Temple, J. R. (2020). On the Front lines of the COVID-19 pandemic: Occupational experiences of the intimate Partner Violence and Sexual Assault workforce. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(11–12), NP9345–NP9366.

Xu, X., & Reed, I. A. (2023). Modernity and the Politics of Newness: Unraveling New Time in the Chinese Cultural Revolution, 1966 to 1968. Sociological Theory 1–26.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ann Swidler and Ryan Hagen for their excellent feedback on an earlier version of this paper, presented at the American Sociological Association meetings in 2022. Many thanks also to members of the Social Theory Workshop at the University of Michigan for their thoughtful comments and critiques.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Science Foundation (Award 2116415).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Sweet, P.L., Glenn, M.C. & Caponi, J. The domestic violence victim as COVID crisis figure. Theor Soc 53, 119–142 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-023-09533-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-023-09533-4