Abstract

Purpose of the Review

Short-term and durable mechanical circulatory support (MCS) devices represent life-saving interventions for patients with cardiogenic shock and end-stage heart failure. This review will cover the epidemiology, risk factors, and treatment of stroke in this patient population.

Recent Findings

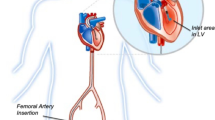

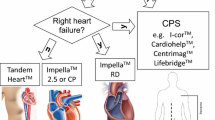

Short-term devices such as intra-aortic balloon pump, Impella, TandemHeart, and Venoatrial Extracorporal Membrane Oxygenation, as well as durable continuous-flow left ventricular assist devices (LVADs), improve cardiac output and blood flow to the vital organs. However, MCS use is associated with high rates of complications, including ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes which carry a high risk for death and disability. Improvements in MCS technology have reduced but not eliminated the risk of stroke. Mitigation strategies focus on careful management of anti-thrombotic therapies. While data on therapeutic options for stroke are limited, several case series reported favorable outcomes with thrombectomy for ischemic stroke patients with large vessel occlusions, as well as with reversal of anticoagulation for those with hemorrhagic stroke.

Summary

Stroke in patients treated with MCS is associated with high morbidity and mortality. Preventive strategies are targeted based on the specific form of MCS. Improvements in the design of the newest generation device have reduced the risk of ischemic stroke, though hemorrhagic stroke remains a serious complication.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of special importance •• Of outstanding importance

Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2016 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133(4):e38-60.

Kohno H, Matsumiya G, Sawa Y, et al. The Jarvik 2000 left ventricular assist device as a bridge to transplantation: Japanese Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2018;37(1):71–8.

Mehra MR, Naka Y, Uriel N, et al. A fully magnetically levitated circulatory pump for advanced heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(5):440–50.

Mehra MR, Goldstein DJ, Uriel N, et al. Two-year outcomes with a magnetically levitated cardiac pump in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(15):1386–95.

Rose EA, Gelijns AC, Moskowitz AJ, et al. Long-term use of a left ventricular assist device for end-stage heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(20):1435–43.

•• Mehra MR, Goldstein DJ, Cleveland JC, et al. Five-year outcomes in patients with fully magnetically levitated vs axial-flow left ventricular assist devices in the MOMENTUM 3 Randomized Trial. JAMA. 2022;328(12):1233–42. This manuscript highlights the 5 -year outcomes comparing the Heartmate 3 to Heartmate II, with improved survival and lower risk of stroke in the Heartmate3 device.

Tsukui H, Abla A, Teuteberg JJ, et al. Cerebrovascular accidents in patients with a ventricular assist device. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;134(1):114–23.

Yuan N, Arnaoutakis GJ, George TJ, et al. The spectrum of complications following left ventricular assist device placement. J Card Surg. 2012;27(5):630–8.

Kato TS, Schulze PC, Yang J, et al. Pre-operative and post-operative risk factors associated with neurologic complications in patients with advanced heart failure supported by a left ventricular assist device. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2012;31(1):1–8.

Kirklin JK, Naftel DC, Pagani FD, et al. Sixth INTERMACS annual report: a 10,000-patient database. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014;33(6):555–64.

Kirklin JK, Naftel DC, Kormos RL, et al. Fifth INTERMACS annual report: risk factor analysis from more than 6,000 mechanical circulatory support patients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32(2):141–56.

Starling RC, Estep JD, Horstmanshof DA, et al. Risk assessment and comparative effectiveness of left ventricular assist device and medical management in ambulatory heart failure patients: the ROADMAP Study 2-year results. JACC Heart Fail. 2017;5(7):518–27.

Stone GW, Ohman EM, Miller MF, et al. Contemporary utilization and outcomes of intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation in acute myocardial infarction: the benchmark registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41(11):1940–5.

Huckaby LV, Seese LM, Mathier MA, Hickey GW, Kilic A. Intra-aortic balloon pump bridging to heart transplantation: impact of the 2018 allocation change. Circ Heart Fail. 2020;13(8):e006971.

Estep JD, Cordero-Reyes AM, Bhimaraj A, et al. Percutaneous placement of an intra-aortic balloon pump in the left axillary/subclavian position provides safe, ambulatory long-term support as bridge to heart transplantation. JACC Heart Fail. 2013;1(5):382–8.

Russo MJ, Jeevanandam V, Stepney J, et al. Intra-aortic balloon pump inserted through the subclavian artery: a minimally invasive approach to mechanical support in the ambulatory end-stage heart failure patient. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;144(4):951–5.

Lauten A, Engstrom AE, Jung C, et al. Response to letter regarding article. Percutaneous left-ventricular support with the Impella-2.5-assist device in acute cardiogenic shock results of the Impella-EUROSHOCK registry. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6(4):e56.

Ouweneel DM, Eriksen E, Sjauw KD, et al. Percutaneous mechanical circulatory support versus intra-aortic balloon pump in cardiogenic shock after acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(3):278–87.

Doersch KM, Tong CW, Gongora E, Konda S, Sareyyupoglu B. Temporary left ventricular assist device through an axillary access is a promising approach to improve outcomes in refractory cardiogenic shock patients. ASAIO J. 2015;61(3):253–8.

Ramzy D, Anderson M, Batsides G, et al. Early outcomes of the first 200 US patients treated with Impella 5.5: a novel temporary left ventricular assist device. Innovations (Phila). 2021;16(4):365–372.

Geller BJ, Sinha SS, Kapur NK, et al. Escalating and de-escalating temporary mechanical circulatory support in cardiogenic shock: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2022;146(6):e50–68.

Cheng R, Hachamovitch R, Kittleson M, et al. Complications of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for treatment of cardiogenic shock and cardiac arrest: a meta-analysis of 1,866 adult patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;97(2):610–6.

Le Guennec L, Cholet C, Huang F, et al. Ischemic and hemorrhagic brain injury during venoarterial-extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Ann Intensive Care. 2018;8(1):129.

• Cho SM, Canner J, Caturegli G, et al. Risk factors of ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes during venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: analysis of data from the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Registry. Crit Care Med. 2021;49(1):91–101. This study describes the main risk factors for ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke in patients treated with ECMO. The risk factors for ischemic stroke were low pre-treatment pH, high pO2, circuit failure, and renal replacement therapy.

Cevasco MR, Li B, Han J, et al. Adverse event profile associated with prolonged use of CentriMag ventricular assist device for refractory cardiogenic shock. ASAIO J. 2019;65(8):806–11.

Mohite PN, Zych B, Popov AF, et al. CentriMag short-term ventricular assist as a bridge to solution in patients with advanced heart failure: use beyond 30 days. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;44(5):e310-315.

Worku B, Pak SW, van Patten D, et al. The CentriMag ventricular assist device in acute heart failure refractory to medical management. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2012;31(6):611–7.

Alli OO, Singh IM, Holmes DR Jr, Pulido JN, Park SJ, Rihal CS. Percutaneous left ventricular assist device with TandemHeart for high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention: the Mayo Clinic experience. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;80(5):728–34.

Schwartz BG, Ludeman DJ, Mayeda GS, Kloner RA, Economides C, Burstein S. Treating refractory cardiogenic shock with the tandemheart and Impella devices: a single center experience. Cardiol Res. 2012;3(2):54–66.

Roy SK, Howard EW, Panza JA, Cooper HA. Clinical implications of thrombocytopenia among patients undergoing intra-aortic balloon pump counterpulsation in the coronary care unit. Clin Cardiol. 2010;33(1):30–5.

Takano AM, Iwata H, Miyosawa K, et al. Reduced number of platelets during intra-aortic balloon pumping counterpulsation predicts higher cardiovascular mortality after device removal in association with systemic inflammation. Int Heart J. 2020;61(1):89–95.

Roka-Moiia Y, Li M, Ivich A, Muslmani S, Kern KB, Slepian MJ. Impella 5.5 versus Centrimag: a head-to-head comparison of device hemocompatibility. ASAIO J. 2020;66(10):1142–1151.

Hassett CE, Cho SM, Hasan S, et al. Ischemic stroke and intracranial hemorrhages during Impella cardiac support. ASAIO J. 2020;66(8):e105–9.

Saeed O, Jakobleff WA, Forest SJ, et al. Hemolysis and nonhemorrhagic stroke during venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2019;108(3):756–63.

Acharya P, Jakobleff WA, Forest SJ, et al. Fibrinogen albumin ratio and ischemic stroke during venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. ASAIO J. 2020;66(3):277–82.

Cavayas YA, Munshi L, Del Sorbo L, Fan E. The early change in PaCO2 after extracorporeal membrane oxygenation initiation is associated with neurological complications. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(12):1525–35.

Shou BL, Ong CS, Zhou AL, et al. Arterial carbon dioxide and acute brain injury in venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. ASAIO J. 2022.

Shou BL, Wilcox C, Florissi I, et al. Early low pulse pressure in VA-ECMO is associated with acute brain injury. Neurocrit Care. 2022.

Hogan M, Berger JS. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT): review of incidence, diagnosis, and management. Vasc Med. 2020;25(2):160–73.

Sokolovic M, Pratt AK, Vukicevic V, Sarumi M, Johnson LS, Shah NS. Platelet count trends and prevalence of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia in a cohort of extracorporeal membrane oxygenator patients. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(11):e1031–7.

Kelly J, Malloy R, Knowles D. Comparison of anticoagulated versus non-anticoagulated patients with intra-aortic balloon pumps. Thromb J. 2021;19(1):46.

Burzotta F, Trani C, Doshi SN, et al. Impella ventricular support in clinical practice: collaborative viewpoint from a European expert user group. Int J Cardiol. 2015;201:684–91.

Jennings DL, Nemerovski CW, Kalus JS. Effective anticoagulation for a percutaneous ventricular assist device using a heparin-based purge solution. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47(10):1364–7.

Seyfarth M, Sibbing D, Bauer I, et al. A randomized clinical trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of a percutaneous left ventricular assist device versus intra-aortic balloon pumping for treatment of cardiogenic shock caused by myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(19):1584–8.

Nishikawa M, Willey J, Takayama H, et al. Stroke patterns and cannulation strategy during veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane support. J Artif Organs. 2022;25(3):231–7.

Omar HR, Mirsaeidi M, Shumac J, Enten G, Mangar D, Camporesi EM. Incidence and predictors of ischemic cerebrovascular stroke among patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support. J Crit Care. 2016;32:48–51.

Lee Y, Weeks PA. Effectiveness of protocol guided heparin anticoagulation in patients with the TandemHeart percutaneous ventricular assist device. ASAIO J. 2015;61(2):207–8.

Le Guennec L, Schmidt M, Clarencon F, et al. Mechanical thrombectomy in acute ischemic stroke patients under venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Neurointerv Surg. 2020;12(5):486–8.

Ziser A, Adir Y, Lavon H, Shupak A. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for massive arterial air embolism during cardiac operations. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;117(4):818–21.

John R, Panch S, Hrabe J, et al. Activation of endothelial and coagulation systems in left ventricular assist device recipients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88(4):1171–9.

Kirklin JK, Naftel DC, Myers SL, Pagani FD, Colombo PC. Quantifying the impact from stroke during support with continuous flow ventricular assist devices: an STS INTERMACS analysis. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2020;39(8):782–94.

Kirklin JK, Pagani FD, Kormos RL, et al. Eighth annual INTERMACS report: special focus on framing the impact of adverse events. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2017;36(10):1080–6.

Izzy S, Rubin DB, Ahmed FS, et al. Cerebrovascular accidents during mechanical circulatory support: new predictors of ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes and outcome. Stroke. 2018;49(5):1197–203.

Milano CA, Rogers JG, Tatooles AJ, et al. HVAD: the ENDURANCE Supplemental Trial. JACC Heart Fail. 2018;6(9):792–802.

Teuteberg JJ, Slaughter MS, Rogers JG, et al. The HVAD left ventricular assist device: risk factors for neurological events and risk mitigation strategies. JACC Heart Fail. 2015;3(10):818–28.

Colombo PC, Mehra MR, Goldstein DJ, et al. comprehensive analysis of stroke in the long-term cohort of the MOMENTUM 3 Study. Circulation. 2019;139(2):155–68.

Fried J, Garan AR, Shames S, et al. Aortic root thrombosis in patients supported with continuous-flow left ventricular assist devices. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2018.

Chivukula VK, Beckman JA, Prisco AR, et al. Left ventricular assist device inflow cannula angle and thrombosis risk. Circ Heart Fail. 2018;11(4):e004325.

Cho SM, Moazami N, Frontera JA. Stroke and intracranial hemorrhage in HeartMate II and HeartWare left ventricular assist devices: a systematic review. Neurocrit Care. 2017;27(1):17–25.

Boehme AK, Pamboukian SV, George JF, et al. Anticoagulation control in patients with ventricular assist devices. ASAIO J. 2017;63(6):759–65.

Starling RC, Moazami N, Silvestry SC, et al. Unexpected abrupt increase in left ventricular assist device thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(1):33–40.

Rogers JG. Changing the carburetor without changing the plugs: the intersection of stock car racing with mechanically assisted circulation. JACC Heart Fail. 2015;3(9):712–4.

Frontera JA, Starling R, Cho SM, et al. Risk factors, mortality, and timing of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke with left ventricular assist devices. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2017;36(6):673–83.

John R, Naka Y, Park SJ, et al. Impact of concurrent surgical valve procedures in patients receiving continuous-flow devices. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;147(2):581–589; discussion 589.

Deshmukh A, Bhatia A, Sayer GT, et al. Left atrial appendage occlusion with left ventricular assist device decreases thromboembolic events. Ann Thorac Surg. 2019;107(4):1181–6.

Cho SM, Moazami N, Katz S, Bhimraj A, Shrestha NK, Frontera JA. Stroke risk following infection in patients with continuous-flow left ventricular assist device. Neurocrit Care. 2019;31(1):72–80.

Aggarwal A, Gupta A, Kumar S, et al. Are blood stream infections associated with an increased risk of hemorrhagic stroke in patients with a left ventricular assist device? ASAIO J. 2012;58(5):509–13.

Willey JZ, Boehme AK, Castagna F, et al. Hypertension and stroke in patients with left ventricular assist devices (LVADs). Curr Hypertens Rep. 2016;18(2):12.

Tabit CE, Chen P, Kim GH, et al. Elevated angiopoietin-2 level in patients with continuous-flow left ventricular assist devices leads to altered angiogenesis and is associated with higher nonsurgical bleeding. Circulation. 2016;134(2):141–52.

Murase S, Okazaki S, Yoshioka D, et al. Abnormalities of brain imaging in patients after left ventricular assist device support following explantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2020;39(3):220–7.

Willey JZ, Demmer RT, Takayama H, Colombo PC, Lazar RM. Cerebrovascular disease in the era of left ventricular assist devices with continuous flow: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014;33(9):878–87.

Mehra MR, Crandall DL, Gustafsson F, et al. Aspirin and left ventricular assist devices: rationale and design for the international randomized, placebo-controlled, non-inferiority ARIES HM3 trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2021;23(7):1226–37.

Netuka I, Ivak P, Tucanova Z, et al. Evaluation of low-intensity anti-coagulation with a fully magnetically levitated centrifugal-flow circulatory pump-the MAGENTUM 1 study. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2018;37(5):579–86.

• Eisen HJ, Flack JM, Atluri P, et al. Management of hypertension in patients with ventricular assist devices: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Heart Fail. 2022;15(5):e000074. This study provides an overview of the data surrounding risks associated with hypertension in patients with an LVAD, and appropriate strategies to treat hypertension.

Feldman D, Pamboukian SV, Teuteberg JJ, et al. The 2013 International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation Guidelines for mechanical circulatory support: executive summary. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32(2):157–87.

Potapov EV, Antonides C, Crespo-Leiro MG, et al. 2019 EACTS Expert Consensus on long-term mechanical circulatory support. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2019;56(2):230–70.

Castagna F, Stohr EJ, Pinsino A, et al. The unique blood pressures and pulsatility of LVAD patients: current challenges and future opportunities. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2017;19(10):85.

Colombo PC, Lanier GM, Orlanes K, Yuzefpolskaya M, Demmer RT. Usefulness of a standard automated blood pressure monitor in patients with continuous-flow left ventricular assist devices. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2015.

Lanier GM, Orlanes K, Hayashi Y, et al. Validity and reliability of a novel slow cuff-deflation system for noninvasive blood pressure monitoring in patients with continuous-flow left ventricular assist device. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6(5):1005–12.

McCullough M, Caraballo C, Ravindra NG, et al. Neurohormonal blockade and clinical outcomes in patients with heart failure supported by left ventricular assist devices. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(2):175–82.

Rettenmaier LA, Garg A, Limaye K, Leira EC, Adams HP, Shaban A. Management of ischemic stroke following left ventricular assist device. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2020;29(12):105384.

Yoshioka D, Okazaki S, Toda K, et al. Prevalence of cerebral microbleeds in patients with continuous-flow left ventricular assist devices. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(9).

Al-Mufti F, Bauerschmidt A, Claassen J, Meyers PM, Colombo PC, Willey JZ. Neuroendovascular interventions for acute ischemic strokes in patients supported with left ventricular assist devices: a single-center case series and review of the literature. World Neurosurg. 2016;88:199–204.

Ibeh C, Tirschwell DL, Mahr C, Creutzfeldt CJ. Medical and surgical management of left ventricular assist device-associated intracranial hemorrhage. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2021;30(10):106053.

Cho SM, Moazami N, Katz S, Starling R, Frontera JA. Reversal and resumption of antithrombotic therapy in LVAD-associated intracranial hemorrhage. Ann Thorac Surg. 2019;108(1):52–8.

Santos CD, Matos NL, Asleh R, et al. The dilemma of resuming antithrombotic therapy after intracranial hemorrhage in patients with left ventricular assist devices. Neurocrit Care. 2020;32(3):822–7.

Cho SM, Canner J, Chiarini G, et al. Modifiable risk factors and mortality from ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes in patients receiving venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: results from the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Registry. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(10):e897–905.

Thiele H, Zeymer U, Neumann FJ, et al. Intraaortic balloon support for myocardial infarction with cardiogenic shock. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(14):1287–96.

Tanaka A, Tuladhar SM, Onsager D, et al. The subclavian intraaortic balloon pump: a compelling bridge device for advanced heart failure. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;100(6):2151–2157; discussion 2157–2158.

O'Neill WW, Kleiman NS, Moses J, et al. A prospective, randomized clinical trial of hemodynamic support with Impella 2.5 versus intra-aortic balloon pump in patients undergoing high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention: the PROTECT II study. Circulation. 2012;126(14):1717–1727.

Ouweneel DM, de Brabander J, Karami M, et al. Real-life use of left ventricular circulatory support with Impella in cardiogenic shock after acute myocardial infarction: 12 years AMC experience. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2019;8(4):338–49.

Cho SM, Mehaffey JH, Meyers SL, et al. Cerebrovascular events in patients with centrifugal-flow left ventricular assist devices: propensity score-matched analysis from the Intermacs Registry. Circulation. 2021;144(10):763–72.

Xie A, Phan K, Tsai YC, Yan TD, Forrest P. Venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for cardiogenic shock and cardiac arrest: a meta-analysis. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2015;29(3):637–45.

Chang CH, Chen HC, Caffrey JL, et al. Survival analysis after extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in critically ill adults: a nationwide cohort study. Circulation. 2016;133(24):2423–33.

Acknowledgements

Joshua Z. Willey reports research funding from the National Institutes of Health (NS R01 121364).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Joshua Z. Willey reports royalties from UptoDate and the American College of Physicians; and consulting fees from Cardiovascular Research Foundation and Abbott Laboratories. Paolo C. Colombo reports consulting fees from Roche, and payment or honoraria from Abbott. The other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Bae, D.J., Willey, J.Z., Ibeh, C. et al. Stroke and Mechanical Circulatory Support in Adults. Curr Cardiol Rep 25, 1665–1675 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11886-023-01985-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11886-023-01985-5