Introduction

The growth in worldwide mobility in the age of globalisation has induced an increasing number of countries to enact measures ensuring extra-territorial political citizenship and to remove barriers to political participation for expatriates and their progeny retaining native or ancestral nationality (Bauböck Reference Bauböck2005; IDEA 2007). Since the 1990s, the number of countries granting voting rights to non-resident citizens has expanded considerably (Lafleur Reference Lafleur2013; Caramani and Grotz Reference Caramani and Grotz2015; Turcu and Urbatsch Reference Turcu and Urbatsch2015); there are nearly 150 countries currently allowing citizens living abroad to vote in homeland elections (Regalia Reference Regalia, Battiston, Luconi and Valbruzzi2022, 71). Italy joined this group between 2000 and 2001, when the constitutional laws no. 1 of 17 January 2000 and no. 1 of 23 January 2001, as well as law no. 459 of 27 December 2001, granted Italian citizens residing abroad both postal voting rights and a parliamentary representation of their own.Footnote 1 Since 2001, postal voting no longer requires the voter to go in person to the polling station of last residence in Italy on election day. Consequently, external participation in Italian elections has increased dramatically, from about 100,000 voters in 2001 to over 1 million in 2022 (Agosta Reference Agosta2006, 466–467; Chiaramonte Reference Chiaramonte2023, 77–78).

Turnout among eligible Italian voters residing abroad is the dimension of their voting behaviour that this article addresses. This essay, therefore, does not examine partisan choices in casting ballots, but it analyses electoral participation and discusses the factors affecting it. Since the first implementation of the new rules (2003 for referenda, 2006 for parliamentary elections), Italy's external turnout has been relatively high by international standards (Ciornei and Østergaard-Nielsen Reference Ciornei and Østergaard-Nielsen2020; Østergaard-Nielsen and Camatarri Reference Østergaard-Nielsen and Camatarri2022), with an average of 20 per cent in the former and 30 per cent in the latter in recent years. Yet, excluding the relatively high but short-lived level of electoral engagement in the period 2006–8 (reaching about 40 per cent in parliamentary elections), the turnout rate in the constituency abroad has steadily declined in the past 15 years or so (Piccio Reference Piccio2020, 920–921). A downward trend in electoral participation has occurred among domestic voters too (D'Alimonte and Emanuele Reference D'Alimonte and Emanuele2023; Tronconi and Tuorto Reference Tronconi and Tuorto2023). Interestingly, the turnout ratio between overseas and domestic constituencies has remained stable around the 0.41 mark for parliamentary elections since 2013. This suggests that if the gulf in participation between voters in Italy and those who live abroad is likely to persist, such a gap has not become any wider or narrower in the last three parliamentary elections.

The all-time-low turnout rate of the 2022 Italian parliamentary elections has renewed interest among scholars seeking to examine voting and non-voting determinants and voter/non-voter characteristics (e.g. Tronconi and Tuorto Reference Tronconi and Tuorto2023; Bordignon and Salvarani Reference Bordignon, Salvarani, Bordignon, Ceccarini and Newell2023), albeit research into the external dimension of such factors and profiles is still notably scant. Yet, Italy offers a stimulating case to analyse transnational politics due to the size, structure, and geographical distribution of its abroad constituencyFootnote 2 as well as its advanced model of external voting and parliamentary representation (e.g. Tintori Reference Tintori2012b; Lafleur Reference Lafleur2013; De Lazzari Reference De Lazzari2019; Piccio Reference Piccio2020; Camatarri Reference Camatarri2021; Battiston, Luconi and Valbruzzi Reference Battiston, Luconi and Valbruzzi2022; Østergaard-Nielsen and Camatarri Reference Østergaard-Nielsen and Camatarri2022; Desantis Reference Desantis2023). Still, scholars have rarely, and by and large only recently, paid close attention to issues relating to the external turnout of Italian voters, e.g. the setting up and managing of the electoral roll abroad and the mailing of paper ballots (Tarantino Reference Tarantino2007), the gap between overseas and domestic turnout (Battiston and Luconi Reference Battiston and Luconi2020), the disparity in turnout rates within the constituency abroad (Vignati Reference Vignati, Battiston, Luconi and Valbruzzi2022), the determinants of external voting, especially from the perspective of the Southern American subdivision (Bertagna Reference Bertagna, Battiston and Luconi2018; Vignati Reference Vignati, Battiston, Luconi and Valbruzzi2022), voter apathy as in the case of recently emigrated young Italians and young voters of Italian descent (Caltabiano and Gianturco Reference Caltabiano and Gianturco2005), and the high percentage of external votes invalidated during the vote counting process (Tarli Barbieri Reference Tarli Barbieri, D'Alimonte and Chiaramonte2007; Desantis Reference Desantis2022).

Overall, past studies have hinted at different factors being potentially responsible for increasing or decreasing the Italian external turnout rate, but the lack of qualitative research in the existing scholarly literature is an objective limitation for making further reflections. In general terms, barriers of a political but also of an administrative, institutional and financial nature are among the main causes that prevent voters residing abroad from casting their ballots (IDEA 2007). Specifically, macro-level factors favouring abstention among external voters include the geographical distribution of seats, lack of systems that provide for on-the-spot voting, lack of access to information, and pre-registration operations, to name just a few. Some other factors may increase turnout, such as the presence of emigrant institutions or geographical proximity between the home and host countries, whereas individual voter characteristics such as country of birth and length of residence abroad may have a demobilising effect (van Haute and Kernalegenn Reference van Haute and Kernalegenn2023, 375).

Single-country case studies point to a set of factors favouring or inhibiting external turnout. In her study of transnational political engagement of Finnish emigrants, Peltoniemi (Reference Peltoniemi2018) found that distance to polling station, interest in politics, length of residency abroad and socio-demographic characteristics such as age and education significantly influenced an emigrant's probability of voting. She posited that transnational political engagement for Finnish emigrants was ultimately a zero-sum relationship: increased engagement in one country led to decreased involvement in the other. The case of French citizens abroad, to take another example, suggests that different factors matter but depended on the voting modality voters chose to adopt. In the study by Dandoy and Kernalegenn (Reference Dandoy and Kernalegenn2021), ballot box voter turnout was affected by the characteristics of electoral districts (e.g. community size, proximity to France geographically and historically, party competition, etc.), whereas internet voter turnout was majorly impacted by the country of residence's economic and infrastructure development (voter turnout was likely to be higher in large and developed countries).

There is a small but growing body of work that seeks to expand our knowledge of external turnout and the determinants of external voting beyond single-country case studies. For instance, a large study by Burgess and Tyburski (Reference Burgess and Tyburski2020) argued that political party mobilisation had a positive effect on extraterritorial voter turnout despite obstacles to overseas mobilisation and long-distance participation. In some instances, mobilising potential external voters produced spillover effects well beyond electoral outcomes. Findings by Ciornei and Østergaard-Nielsen (Reference Ciornei and Østergaard-Nielsen2020) highlighted the importance of the existence of host–home country linkages on transnational turnout, especially for emigrants from developing nations residing in countries with solid democratic institutions. Szulecki et al. stressed the need to locate determinants of external voting instead of looking for ‘monocausal explanations or even for the most important factor among many’ (2021, 1004). External voters’ desire, mobilisation and ability to vote, Szulecki et al. argued, interact with country of residence, country of origin and transnational factors. The authors concluded that the motivation of external voters to vote may be influenced not only by objectively measured factors, such as country of residence or origin, but also by subjective factors and perceptions of the legitimacy of external voting.

The aim of this article is twofold. First, we expand our still limited empirical knowledge of factors influencing Italian external turnout by utilising survey data collected among Italian voters living abroad (n = 1,368). Specifically, we will be exploring individual (micro-)level factors (i.e. who votes and who does not, and why), which have so far been largely overlooked in the literature, and indirectly macro-level ones, by means of exploring the respondents’ opinions of voting reform proposals that may incentivise voting (adoption of electronic voting) or restrict the voter base but potentially increase the turnout (on demand vs. automatic registration). Second, we situate our survey findings and reflections against the broader transnational turnout and migration studies literature, thus enhancing the scholarly discussion on transnational politics. The main research questions asked in this study are as follows: (1) Do voter characteristics influence turnout in parliamentary elections and referenda among external Italian voters, and, if so, how?; (2) Which factors are potentially responsible for increasing or decreasing the Italian external turnout rate?; and (3) Do external voters support voting reform proposals that may in principle increase voter turnout?

Some voter characteristics are known to augment the desire to participate in elections, hence positively influence external turnout rates; for instance, voters born in the country of origin are more likely to vote in homeland elections than voters born in the country of residence (e.g. Mügge et al. Reference Mügge, Kranendonk, Vermeulen and Aydemir2021). Conversely, ‘cultural’ distance from the country of origin may discourage mobilisation to vote, hence adversely affect participation in homeland elections and politics. Non-resident citizens who are not proficient in the language in which homeland debates and elections are held may not meaningfully exercise their external voting rights, or exercise them at all, as their political engagement is language dependent (Bonotti and De Lazzari Reference Bonotti and De Lazzari2023). Voter characteristics notwithstanding, location-independent voting methods such as proxy, postal or email are likely to increase voter participation (Szulecki et al. Reference Szulecki, Bertelli and Erdal2021). Following these arguments, we hypothesise the following: (H1) External voters born in Italy are more likely to participate in homeland elections than those born abroad; (H2) ‘Cultural’ distance from the country of origin may diminish the likelihood to vote; and (H3) External voters are likely to support voting reform proposals that may increase voter participation.

The next section places Italy's introduction and implementation of external voting within a historical context, highlighting the initial expectations in terms of mobilisation and participation as well as the anxieties generated by the shortcomings of the new legislation. The third section focuses on turnout in overseas constituencies, paying specific attention to the differences among different geographic subdivisions and types of communities. The remaining sections test our hypotheses by probing the survey data collected among Italian citizens abroad.

Italian external voting and its shortcomings for political participation and representation

In 1921, Camillo Pellizzi, a Fascist intellectual lecturing in London, complained that, notwithstanding their steadfast patriotism, he and his fellow expatriates were forcibly excluded from their motherland's political life because they were unable to travel back to Italy to vote on election day (Salvati Reference Salvati2021, 97–98). His grievance highlighted a few issues involving Italian migrants’ political rights that the liberal regime would bequeath to the postwar Republic. On the one hand, expatriates never lost the suffrage, providing that they retained their Italian citizenship, but they had to return to their native country to cast their ballots there. On the other, claims for actual opportunities to vote in Italian elections seemed to come primarily from rightist migrants. The misperception that conservative Italians in foreign countries were more likely to mobilise politically delayed the implementation of external voting rights for decades after the establishment of the Republic (Colucci Reference Colucci, Bevilacqua, De Clementi and Franzina2002, 600–601, 606). It was hardly by chance that, after decades of postponements, Italy eventually enacted postal voting for migrants during Silvio Berlusconi's conservative government and that the leading sponsor of the provision was Mirko Tremaglia, an unrepentant associate of Benito Mussolini's former Social Republic (Choate Reference Choate2007, 728–729).

Pellizzi's criticism also demonstrates the long history of overseas Italian citizens’ call for appropriate means to exert the suffrage. Indeed, the campaign for external voting rights began even earlier, during the first and second conference of Italians abroad in 1908 and 1911 (Napolitano and Di Stefano Reference Napolitano and Di Stefano1969, 3), and it gained momentum in the postwar decades as emigration from Italy resumed after its pause following the Fascist regime's 1927 anti-expatriation policies and the military conflict. A new conference of overseas Italians claimed again external voting rights as early as 1946, in view of the elections of a constitutional convention (Italiani nel Mondo 1946). At the height of the Cold War, the Communist Party, too, was somewhat interested in the emigrants’ actual enfranchisement as it chartered ‘red trains’ to bring tens of thousands of expatriates working in nearby European nations to the polls in Italy on election day (Betti Reference Betti1972). Efforts to secure external voting rights also involved Italians in countries that were no longer major destinations for the outflow from the peninsula after the Second World War, such as the United States and Uruguay (LaGamba Reference LaGamba1978, 7; Sergi Reference Sergi2014, 185).

Against this backdrop, one would reasonably have expected Italians abroad to seize the chance of voting by mail to participate in homeland elections in large numbers over time. This, however, has not been what has actually happened. Both the set of procedures enacting postal voting and the specific characteristics of the current potential electorate have affected the trend in turnout for overseas Italian citizens.

The 2000–1 provisions offered Italy an opportunity to reach out to its so-called diaspora and to create a political space across national borders linking voters at home and overseas (Lafleur Reference Lafleur2013). The constituency abroad is not an Italian peculiarity (Hutcheson and Arrighi Reference Hutcheson and Arrighi2015). Italy's model, however, makes a few constitutionalists frown due to lack of legitimacy on the grounds that political representation should be somehow connected to the territory of the state (Tarli Barbieri Reference Tarli Barbieri2022, 151). The reserved seats for residents abroad were apparently conceived as a sort of electoral ‘compensation’ (Montacutelli Reference Montacutelli2003, 101) for the Italian state's earlier alleged neglect of its migrants despite the latter's ‘hardships and sacrifices’ (Tremaglia Reference Tremaglia2006, 130). Yet, the real purpose of that mechanism was not to accommodate the expatriates’ call for political representation, but to prevent Italians abroad from having a significant influence on the outcome of their homeland's elections (Vaccara Reference Vaccara and Mignone2008, 86–88). Lawmakers feared that, in view of the nation's mass exodus, enfranchised Italian citizens from, for example, a Neapolitan background in the world would outnumber the eligible voters residing in Naples and could, therefore, shape the city's delegation to parliament. Expatriates were consequently confined to a symbolic representation (Tintori Reference Tintori and Licata2013, 174), especially because the ratio between eligible voters and the number of members of parliament penalises citizens abroad. In the 2022 elections, for example, there was one deputy for every 115,300 eligible voters living in Italy and one for every 395,332 residing overseas (Ministero dell'Interno 2022a). Furthermore, taken as a whole, seats abroad account for roughly only 2 per cent of the total number of deputies and senators, as opposed to percentages spanning from 3.6 per cent in France to 8.3 per cent in Tunisia in the lower chambers, for example (Balduzzi and Prodi Reference Balduzzi and Prodi2020).

Italians abroad seem conscious that the mechanics to enjoy their external rights cripple their actual political clout. Turnout in the overseas constituency has undergone a steady decline since 2006, the year of the first implementation of the postal vote, dropping from 38.9 per cent to 26.4 per cent in 2022 in the elections for the Chamber of Deputies and from 39.6 per cent to 26.1 per cent in those for the Senate. The only increase – though quite limited – took place between 2006 and 2008, when participation rose to 39.6 per cent in the vote for the Chamber and to 40.3 per cent in that for the Senate. Such a growth occurred in the wake of the 2006 election of four progressive overseas senators who had enabled Romano Prodi to form a new centrist government and to replace Berlusconi and his conservative coalition as premier (Novella Reference Novella2006). In 2006, therefore, the overseas vote did count because Italians abroad made a difference. That awareness, however, stimulated only a short-lived mobilisation because in all the subsequent elections the political choices of the voters in the world were irrelevant to the creation of a majority in the Italian parliament.

The so-called Lupi amendment has further limited political representation for Italians overseas. This 2017 change to the rules regulating the qualifications to stand for parliament in the constituency abroad enabled candidates living in Italy to run for overseas seats and to represent expatriates (Alberico Reference Alberico2018, 9–12). A letter to La Voce di New York called the Lupi amendment an ‘immoral atrocity for democracy’ and ‘an actual betrayal of Italians abroad’ because it potentially infringed their representation and benefited politicians who had never lived outside Italy's borders (Bernabucci Reference Bernabucci2017). That theoretical hypothesis became real in 2018, when Francesca Alderisi, a Rome-based host for RAI International television programmes, was elected to the Senate on the ticket of Forza Italia in the Northern and Central America subdivision (Pozzi Reference Pozzi2018). Likewise, four years later, Andrea Crisanti – a virologist living and working in Padua, who had gained significant popularity during the COVID-19 pandemic – won a senatorial seat for the Democratic Party in the European subdivision (Ferro Reference Ferro2022).

The enforcement of external voting rights for Italian nationals involves other shortcomings. Citizens living abroad are not placed on an equal footing. The opportunity for postal voting applies only to those residing in countries where, at the sole discretion of the Italian government, suffrage can be freely and secretly exerted. Furthermore, absentee ballots can be mailed only in states that have signed agreements with Italy to that purpose. In the 2022 elections, 19 countries were excluded (Ministero dell'Interno 2022b).

Compliance with material procedures has also interfered with the actual representation of voters abroad. Expatriates have frequently complained about delays and miscarriages concerning the receipt of packages with the ballots that Italian consulates are required by law to mail to registered voters in their respective districts and that recipients must return by the Thursday preceding the election day to be counted. Such grievances continued to be filed as late as 2022, more than two decades after the enactment of the 2000–1 reform (Pesce Reference Pesce2022; Rinaldi Reference Rinaldi2022). Shipping ballots by mail also makes it difficult to ascertain whether they are marked by the legitimate addressees. Adriano Cario's loss of his seat in the Senate because more than 2,000 ballots in his favour from South America bore the same handwriting in the 2018 elections highlighted the risks of a system that entrusts political representation to the mail (Llorente Reference Llorente2021).

Against this backdrop, it is hardly surprising that most Italians abroad are rather sceptical with regard to the effectiveness of the postal vote to express their electoral choices. According to a recent survey, for instance, four in five would replace the current procedures with electronic voting (this is discussed in more detail below; see also Battiston Reference Battiston, Battiston, Luconi and Valbruzzi2022, 178–181). Nonetheless, in spite of Italy's efforts to exploit external voting rights as a means to establish or consolidate transnational ties with its nationals overseas, a few do not seem to be interested in this project at all. As one of them remarked about the attitude of the Italian community in Porto Alegre during the campaign for the 2022 parliamentary elections, which overlapped with the race for president of Brazil, ‘We discuss about Lula and Bolsonaro here; Italy is distant’ (Nastasi Reference Nastasi2022, 37). Lack of identification with Italy affects primarily present-day brain-drain migrants who either consider themselves less as Italian nationals than as citizens of the world, or who even reveal hostility towards their native country, on the grounds that Italy at least indirectly forced them to move abroad to improve their professional lives or to achieve a better education (Cucchiarato Reference Cucchiarato2010). To many of them, the ruling class of their motherland is generally ‘unfit’ and there is an ‘abyssal distance’ between it and reality, which hardly stimulates their involvement in Italian politics (Ziniti Reference Ziniti2022).

The turnout in the Italian constituency abroad

From the mid- to the late 2000s, Italian voters abroad participated in relatively high numbers in homeland elections, but since then the turnout has recorded a declining trend in percentage points. In contrast, the number of eligible external voters has boomed. By enacting postal voting for citizens residing abroad both temporarily (though with certain conditions) and permanently, including for those who reclaimed Italian citizenship through jus sanguinis legislation and those born abroad, the Italian external voting model has effectively allowed the largest possible number of external voters to be included in the electoral rolls. In just under two decades, the number of external voters has doubled, from 2.3 million (2003) to 4.7 million (2022), due to ongoing emigration, the effects of citizenship by descent legislation,Footnote 3 and natural growth. To appreciate this remarkable growth, one should consider the negative demographic trend affecting the domestic voter cohort, which declined from 47.1 million to 46.1 million during the same period.

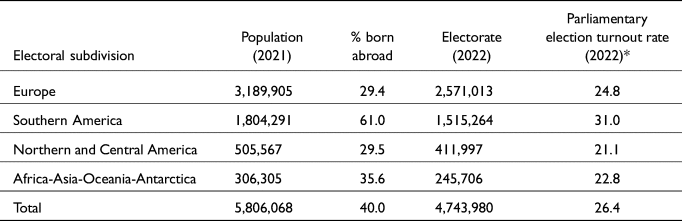

The twin phenomena of declining turnout and growing voter base have characterised only in part the Italian constituency abroad. The geographical distribution and composition of voters are two other defining features of this cohort. Where Italian external voters are mostly concentrated by subdivision or country of residence is ascribable by and large to past European and transatlantic migrations: 54 per cent of voters live in Europe and 40 per cent in the Americas. But it also illustrates where Italian citizenship by descent was most requested (see the higher percentage of those born abroad in the Southern America subdivision in Table 1). The subdivisional differences of the external turnout point to diverse types of voting participation. Limitations notwithstanding,Footnote 4 the turnout rate can be a useful tool for mapping levels of electoral engagement within the overseas constituency, rather than between the overseas and domestic constituencies.

Table 1. Italians living abroad, selected data

Source: Authors’ own compilation based on Italian government data and other sources. Specifically, for the Italian abroad population data (at 31 December 2021), see Gazzetta Ufficiale no. 32, 8 February 2022. For the percentage of the population born abroad (at 31 December 2021), see Licata (Reference Licata2022, 419–423) – please note that Central America is grouped together with the Southern, not Northern, America subdivision. For the electorate and parliamentary election turnout data (25 September 2022), see the Eligendo portal of the Ministry of the Interior (https://elezioni.interno.gov.it/).

*Chamber of Deputies data only.

A reading of the turnout rate of the constituency abroad by subdivision indicates, for instance, the existence of a noticeable disparity in participation between Southern America, the second largest subdivision, and the remaining areas (Figure 1). Particularly striking is the turnout gap between the two subdivisions on the American continent, reaching its maximum in 2008 (14.7 percentage points) and its minimum a decade later in 2018 (2.6 percentage points). Since 2022, this gap between Southern and Northern/Central America has been widening again (9.9 percentage points). If a ‘substantial homogeneity’ was achieved in 2018 among all four subdivisions (Vignati Reference Vignati, Battiston, Luconi and Valbruzzi2022, 89), the participation rate in the 2022 parliamentary election was a case of déjà vu, with Southern America bucking the trend.

Figure 1. Turnout rate of the constituency abroad by subdivision, Italian parliamentary elections, 2006–22, Chamber of Deputies

Source: Authors’ own compilation based on data from the Ministry of the Interior (https://elezioni.interno.gov.it/).

The gap between participation in referenda and parliamentary elections, held earlier or later for comparison purposes, is much less pronounced among voters residing abroad than among domestic voters, pointing to the existence of a small but highly engaged core of Italian external voters (Vignati Reference Vignati, Battiston, Luconi and Valbruzzi2022), especially in the Southern America subdivision. A disparity in participation, again, between the Southern America subdivision and the other three subdivisions is also evident in the external turnout at referenda, especially from 2003 to 2011, and since 2022 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Turnout rate of the constituency abroad by subdivision, Italian referenda, 2003–22

Source: Authors’ own compilation based on data from the Ministry of the Interior (https://elezioni.interno.gov.it/). Note: 2016a (April referendum); 2016b (December referendum).

The peculiarity of the turnout rate in Southern America is even more salient if one considers that this subdivision, unlike the other three, is made up mainly of Italian citizens by descent – namely, those born abroad, some of whom have never set foot in Italy or mastered the Italian language (Tintori Reference Tintori2011, 176–177). For some scholars, the high turnout recorded in some countries in South America may not express a genuine desire to participate in homeland politics, but rather a quid pro quo in the hope of obtaining economic benefits, implying instances of exchange votes (Tarantino Reference Tarantino2007, 52; Tintori Reference Tintori2011, 177–179). For others, this idiosyncrasy is only apparently a paradox. A number of factors – including compulsory voting traditions in Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay, along with the unfounded fear that non-voting will result in cancellation from the Anagrafe degli italiani residenti all'estero (AIRE, Registry of Italians Residing Abroad) – may play a part in bringing out voters, but the main drive is to be found instead in the mobilisation by local political parties such as the Movimento associativo italiani all'estero (MAIE, Associative Movement of Italians Abroad) and the Unione sudamericana emigrati italiani (USEI, South American Union of Italian Emigrants) (Bertagna Reference Bertagna, Battiston and Luconi2018). If voters born in the country of residence are said to be less likely to vote in homeland elections than voters born in the country of origin (e.g. Mügge et al. Reference Mügge, Kranendonk, Vermeulen and Aydemir2021), the case of Italians in the Southern American subdivision supports the argument put forward by Burgess and Tyburski (Reference Burgess and Tyburski2020) on the positive effect on voter turnout of political party mobilisation, which in the case of the abovementioned subdivision is a direct expression of local Italian ethnic associations and clubs.

Another way to map the external turnout, other than by subdivision, is by the size of voter communities. According to 2022 data, 11 countries accounted for 84 per cent of Italian voters living abroad and each was home to over 100,000 voters. A further 11 per cent lived in 19 countries, with a voter population comprised between 10,000 and 100,000. The remaining 5 per cent were scattered in more than 100 countries and territories, where voters in each totalled fewer than 10,000. Turnout data for parliamentary elections indicate that small communities perform consistently better than larger ones (see Figure 3). On average, during the period 2006–22, small communities recorded turnout levels of 13.7 percentage points and 15.2 percentage points higher than medium-size (10,000 to 100,000) and large (above 100,000) communities of voters respectively.

Figure 3. Turnout rate of the constituency abroad by size of voter community, Italian parliamentary elections, 2006–22, Chamber of Deputies

Source: Authors’ own compilation based on data from the Ministry of the Interior (https://elezioni.interno.gov.it/). Note: Countries and territories of the constituency abroad have been grouped into three categories based on the number of registered voters: (1) under 10,000; (2) 10,000–100,000; and (3) over 100,000.

The greater level of participation uncovered at the periphery of the external electorate appears to support empirical studies that have found a higher degree of transnational mobilisation in smaller emigrant communities (Ciornei and Østergaard-Nielsen Reference Ciornei and Østergaard-Nielsen2020). The make-up of the electorate and local dynamics could partly further explain the propensity to higher turnouts of small communities, as the case studies of the Italian voter communities in the Dominican Republic and Norway, for instance, tend to suggest (Puliga Reference Puliga, Battiston and Luconi2018; Miscali Reference Miscali2021).

Those who do not vote: a description of Italian non-voters abroad

As we have seen in the previous section, turnout in the overseas constituency has shown different trends across the four subdivisions, although a downward homogenising pattern can be observed. Thus far, however, we have conducted an ecological analysis, relying on voting (and non-voting) data within and across specific electoral districts. To explore the socio-demographic characteristics of non-voters abroad (and, in the next section, their motivations for electoral participation or abstention), we will use data from an online survey conducted shortly after the 2020 constitutional referendum, which, in addition to residents of Italy, involved about 4.5 million Italians of voting age living abroad.

Specifically, the survey was administered in the form of a questionnaire to Italian citizens self-identified as residents abroad and eligible to vote between 22 September and 23 December 2020. The key criteria for inclusion in the survey were to be eligible to vote in Italian parliamentary elections and referenda (that is, to be Italian citizens regardless of place of birth or of holding multiple citizenships), to be of voting age, and to reside abroad. The respondents came from a non-probability sampling conducted online. To be precise, we adopted a so-called snowball sampling design (Corbetta Reference Corbetta2003), through the identification of several groups (mainly online) of Italian citizens not resident in Italy who contributed to the dissemination and circulation of the survey. This was necessary as the electoral roll of voters abroad, whose database is made up of AIRE and consular records, is not publicly available.

To disseminate the survey as widely as possible and recruit a diverse range of potential respondents, we adopted the following strategy. The survey link was published in over 300 Facebook groups of Italians abroad (typically, groups titled Italiani in … [‘Italians in …’]), including groups of descendants of Italians. Only groups that were deemed active – namely, showing recent wall posting activity – and that had at least 100 group members were selected. The survey was also disseminated among organisations of Italians abroad or institutions associated with Italian migrant communities, some of which agreed to post and/or share the link, as well as to a list of contacts built up over several years of engagement with the representatives of Italian political parties abroad and Italian organisations across the world. To guarantee an adequate geographical distribution of respondents, the survey link was distributed among Facebook groups, organisations and contacts located in cities, regions and countries from all four electoral subdivisions. Additionally, the survey questionnaire was made available in five foreign languages besides Italian – English, French, German, Portoguese and Spanish – to incentivise the participation of Italian voters with limited or no Italian language skills. A total of 1,587 respondents took part in the survey, of whom 89.1 per cent reported being enrolled in AIRE. After eliminating incomplete responses, the number of questionnaires useful for our analysis was 1,368.

Notably, this interview collection process, especially when carried out online, is not immune from the risk of selection bias (Bethlehem Reference Bethlehem2010). Indeed, certain categories or groups of people (e.g., in our case, older individuals and those less technologically equipped) are under-represented, while more educated people and younger generations, who are arguably more au fait with the latest internet technologies, are over-represented within the sample.Footnote 5

That said, due to the sampling methods used in this survey, the respondents as a whole cannot be considered representative of the entire population of Italians living abroad. However, given the predominantly exploratory nature of this study – and, moreover, in an area still little touched by research conducted using surveys and where electoral data, as far as Italians living abroad are concerned, are still insufficient or missing – the probabilistic nature of the sampling should not be considered an insurmountable obstacle. Once the limitations arising from such a sample design are recognised, analyses of the data obtained from the survey can offer valuable information on the characteristics of Italians abroad, their preferences and the quality of political representation.

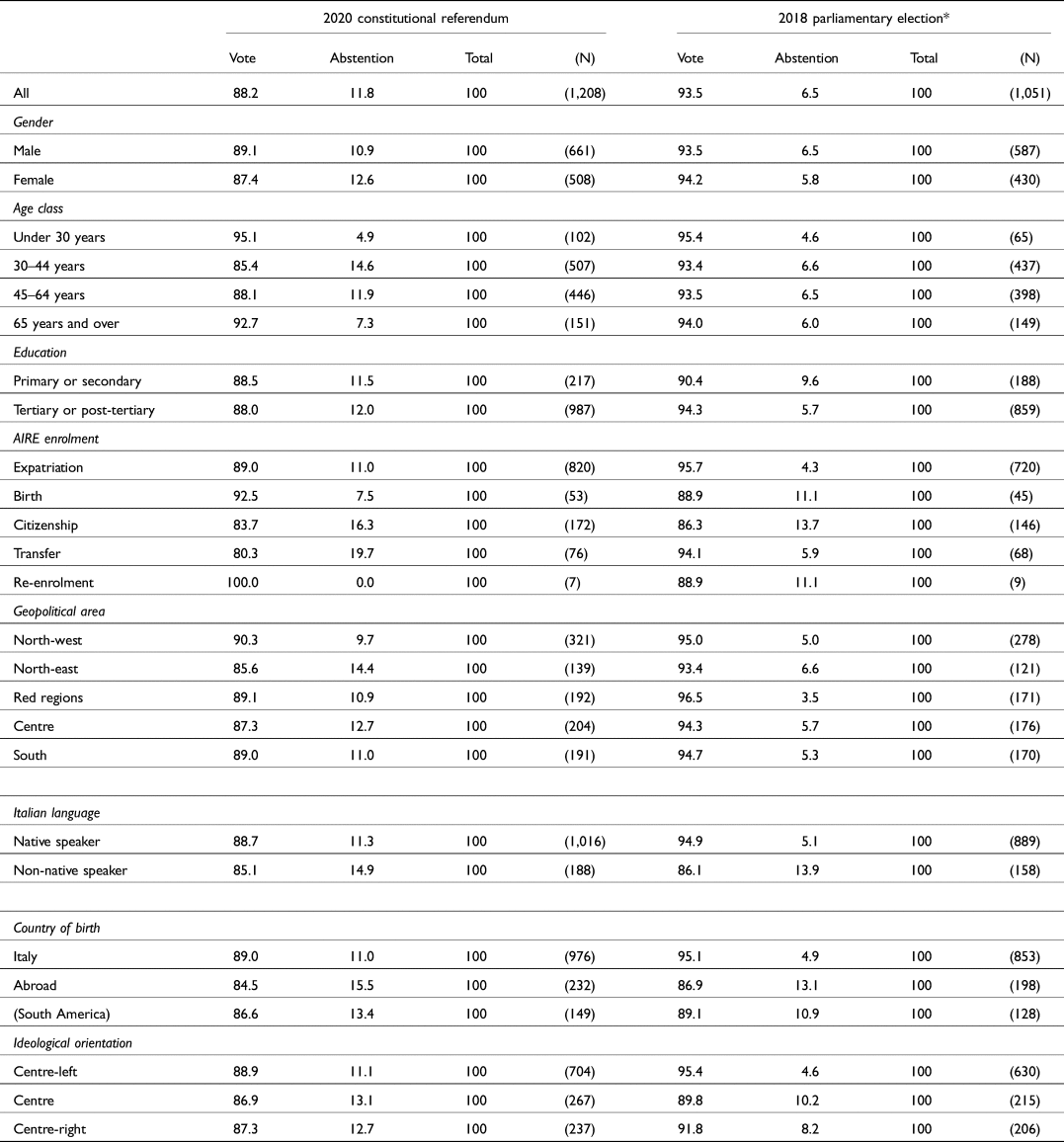

Going into the details of our analysis, in Table 2 we examine the propensity to vote (or not to vote) based on certain socio-demographic characteristics of respondents within the realm of Italians abroad. Specifically, we asked respondents whether they had participated in two recent elections – the 2020 constitutional referendum (regarding the reduction in the number of parliamentarians) and the parliamentary election in 2018.

Table 2. Electoral participation in the constituency abroad in the 2020 constitutional referendum and 2018 parliamentary election, by socio-demographic characteristics (% values)

Source: Authors’ own compilation based on data provided by the Italians abroad 2020 post-election survey. Note: To reconstruct the geopolitical area, respondents were asked to indicate the region of last residence. Respondents who were not born in Italy or had not resided there for at least five years were excluded from the count. The division of Italian regions into the five geopolitical areas is as follows: north-west (Valle d'Aosta, Piedmont, Liguria, Lombardy); north-east (Veneto, Trentino Alto-Adige, Friuli Venezia-Giulia); ‘red regions’ (Emilia-Romagna, Tuscany, Marche, Umbria); centre (Lazio, Abruzzo, Sardinia); south (Molise, Campania, Basilicata, Puglia, Calabria, Sicily). Left–right political orientation derives from respondents’ self-placement on a ten-point scale. The answers have then been collapsed into three categories: centre-left (1–4); centre (5–6); centre-right (7–10).

*Chamber of Deputies data only.

The first finding to be noted, as is also the case in similar studies using survey data (Selb and Munzert Reference Selb and Munzert2013; DeBell et al. Reference DeBell, Krosnick, Gera, Yeager and McDonald2020), is the overestimation of turnout: in surveys, people are less likely to declare their abstention and, accordingly, a turnout gap is produced ranging from 10 to 20 percentage points. While aware of this aspect, here we are mainly interested in investigating the set of characteristics of those who claim not to have taken part in the electoral process, in order to draw an identikit of the abstentionist among Italian citizens abroad. As can be seen, our analysis of individual data also reveals a turnout gap between voting in parliamentary elections and in popular referenda. In particular, the latter are considered – as happens in Italy and elsewhere – as ‘second-order elections’ (Reif and Schmitt Reference Reif and Schmitt1980), so the incentives for participation are lower. In the two elections considered here, the non-voting percentage halves between the 2020 referendum (11.8 per cent) and the 2018 elections (6.5 per cent). Thus, in this case, a similarity between the electorate residing in Italy and those living abroad is confirmed.

As for the relationship between gender and voting, the data included in Table 2 indicate only a slightly higher propensity to vote among men (by about one and a half percentage points in the 2020 constitutional referendum), in line with the main theories on political participation and social centrality/marginality (Tuorto Reference Tuorto2022). What is more, such a small difference is in line with the data pertaining to the Italian context, where gender gap in relation to abstention has been progressively shrinking (Tuorto Reference Tuorto, Bellucci and Segatti2011). It is also interesting to note that no significant differences emerge when considering the age of Italian voters abroad. However, it is the under-30s and those aged 65 and over who were the most active in the 2020 constitutional referendum and the 2018 parliamentary elections. Due to the nature of our sample (within which highly educated voters largely prevail), no noteworthy differences in education emerge for the 2020 referendum, while they do emerge in the case of the 2018 parliamentary elections. In the latter case, there is an abstention gap of nearly 4 percentage points between voters with primary or secondary education and those with tertiary or higher education (9.6 per cent and 5.7 per cent, respectively).

So far, we have highlighted some similarities between non-voters in Italy and non-voters living abroad. However, there is one aspect where the two constituencies (domestic and external) clearly diverge. This is specifically linked to subcultural territorial traditions on civic engagement and electoral participation (Putnam Reference Putnam1994; Diamanti Reference Diamanti2009). Indeed, while abstentionism in Italy is less pronounced in the so-called ‘red regions’ (Emilia-Romagna, Tuscany, Umbria and Marche – heirs of the social-communist subculture) or in the regions of northern Italy, in the overseas constituency these influences disappear. In other words, the respondents’ region of birth (and, therefore, their geopolitical zone of reference) does not seem to have any impact on the propensity to vote. Thus, the spatial effect on voting seems to work only (and remain) at the local level and does not turn into a structural, long-term characteristic of individual voters.

What really matters in the case of Italians abroad are, instead, two characteristics that bring them closer, on a cultural level (lato sensu), to their country of origin: on the one hand, being born in Italy and, on the other hand, being a native speaker of Italian. Arguably, these two characteristics help to explain the different degrees of abstentionism among Italians living abroad. In fact, among those who are Italian native speakers, abstention in the 2020 referendum decreases by 3.6 percentage points, while in the 2018 general election the gap is even greater, touching nearly 9 percentage points. A similar trend is also found when taking into consideration the country of birth (in Italy or abroad) of the respondents: in the 2018 general elections, almost three times as many non-voters abroad were not born in Italy compared with those who were born in Italy (13.1 per cent and 4.9 per cent, respectively).

As mentioned, the link to one's country of origin seems to explain, better than any other demographic variables (such as gender or age), the different propensity of respondents towards abstention. The closer or more recent the link, the greater the predisposition to go to the polls. Incidentally, if gender and age are crucial variables explaining voting behaviour (and its change across time) of Italian ‘domestic voters’ (Bellucci and Segatti Reference Bellucci and Segatti2011), for those living abroad the impact of these socio-demographic variables is virtually negligible. We can further observe this aspect by also taking into consideration the different motivations for Italians abroad to register with AIRE. In particular, as can be seen, it is above all the expatriate community (more prevalent in the European constituency and often possessing a native level of Italian) that had a greater propensity to vote in the 2018 parliamentary election: in this case, the non-voting proportion is limited to 4.3 per cent, while it reaches the highest level (13.7 per cent) among voters whose Italian citizenship was granted by descent.

Finally, regarding the relationship between ideological orientations and abstention, in Table 2 we divided respondents according to their self-placement on the traditional left–right scale. While not too marked differences emerge between the three groups of respondents (centre-left, centre and centre-right), abstention is lower among the two most ‘extreme’ categories (centre-left and centre-right), both in the 2018 parliamentary election and in the 2020 referendum. It is voters in the centre of the political space, without a marked ideological connotation, who show higher levels of abstention: 13.1 per cent in the referendum and 10.2 per cent in the parliamentary election.

Why people do not vote: exploring the motivations for voting abstention abroad

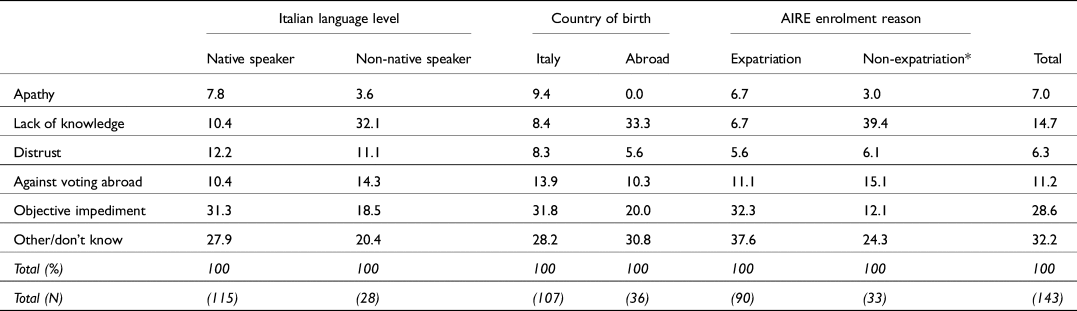

To explore the motivations of voters abroad behind voting abstention, respondents in the survey were asked to indicate the main reason for their decision not to vote. In addition to the residual (‘Other’) category of those who did not respond or gave other minor motives, five main reasons for abstention can be identified, which we summarised with the following labels: (1) apathy; (2) lack of knowledge; (3) distrust; (4) against voting abroad; and (5) objective impediment (see Table 3). In the latter category, answers are included that relate to both a physical impediment (e.g. for COVID-related reasons) and an objective impediment, such as failure to deliver (on time) the ballot envelope. In this regard, it is important to note that nearly 70 per cent among those who indicated an impediment traced that impediment to the manner or timing of delivery of the envelope containing the ballot(s), as far as the 2020 constitutional referendum was concerned.

Table 3. Reasons for not voting in the 2020 constitutional referendum by selected characteristics (% values)

Source: Authors’ own compilation based on data provided by the Italians abroad 2020 post-election survey. Note: The wording of the question regarding the 2020 constitutional referendum was: ‘If you did not vote (or do not remember having voted), what was your main reason?’ In addition to the option of not casting a vote, respondents were offered a shortlist of answer choices: 1. [Apathy] ‘I am not interested in Italian elections and/or referenda’; 2. [Lack of knowledge] ‘I lacked the necessary knowledge to participate in Italian elections and/or referenda’; 3. [Distrust] ‘I felt my vote would not make a difference’; 4. [Against voting abroad] ‘I should not have been granted the right to vote in Italian elections and/or referenda in the first place’; 5. [Objective impediment] This includes answers related to both a physical impediment (e.g. for COVID-related reasons) and an objective impediment; [Other] A residual category including those who did not respond or gave other minor reasons.

*This category includes those enrolled in AIRE by birth and citizenship but excludes those enrolled by transfer and re-enrolment.

The picture that emerges from the data analysis reveals a clear distinction between ‘emigrant voters’ – i.e. those born in Italy, native speakers of Italian and enrolled in AIRE for expatriation – and ‘descendant voters’ – i.e. those born abroad, with a non-native level of knowledge of Italian and registered with AIRE for reasons unrelated to expatriation (this category includes only those enrolled by birth and citizenship). In the first group (emigrants/expatriates), the main reason behind non-voting is that of objective impediment (always greater than 30 per cent), mainly related to a delay in receiving the envelope with the ballot or temporary absence from the registered address. Instead, among descendent voters who show less attachment to Italy and its language, the main reason for not voting (higher than 30 per cent) lies in the lack of knowledge about national politics and the choices at the centre of the electoral competition (in this case the binary choice of voting ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to constitutional amendments).

As for other reasons explaining abstentionism, opposition to the right to vote for Italians abroad concerns, overall, 11.2 per cent of non-voters and tends to be higher within the group of descendent voters. In contrast, reasons that have to do with political apathy or distrust of one's own ability to influence decisions in the Italian political system reach, overall, 14 per cent of responses and are prevalent among expatriates, perhaps also as a form of protest or detachment towards the country they emigrated from.

What do voters abroad think of electronic voting and on-demand proposals?

As we have just seen, in many cases the main reason for non-voting abroad was related to the quality and effectiveness of the electoral process, not only at the counting stage but also at the stage of receiving the ballot paper. Moreover, since we are dealing with a population that can be very mobile (this is especially the case of the more recent expatriates), the chances that the electoral envelope is mailed to the wrong address abroad remain high. To minimise issues of this nature, which negatively affect the electoral integrity of overseas voting, scholars and politicians have proposed, at least on an experimental basis, the adoption of electronic voting, taking advantage of new digital technologies.Footnote 6 At the same time, to avoid delays or frauds in both the initial and final stages of the electoral process, it has been proposed to reserve the right to vote for Italians living abroad only to those who expressly request it. As far as these two proposals are concerned (electronic voting and voting on demand), we surveyed the opinion of our respondents and cross-referenced the data with a set of socio-demographic characteristics (see Table 4).

Table 4. Opinion of Italians abroad on the possibility of voting only on demand and electronic voting, by socio-demographic characteristics (% values)

Source: Authors’ own compilation based on data provided by the Italians abroad 2020 post-election survey. Note: The wording of the two questions was: ‘Do you agree with the following propositions? [Very much; Somewhat; A little; Not at all]: a) Only Italian citizens living abroad who apply for it can exercise their right to vote; b) Italian citizens abroad are allowed to vote electronically.’ The original four-point Likert scale was collapsed into a two-category scale (agree vs. disagree). For the details of the socio-demographic variables, see Table 2.

Our respondents are overwhelmingly in favour of the introduction of e-voting. Indeed, more than 80 per cent of the sample supports this proposal, showing a level of support even greater than that of those Italians voting in Italy (Valbruzzi Reference Valbruzzi2023). Moreover, in contrast to what might have been expected, it is mainly the older generations (45 years and older) who are most supportive of introducing electronic voting, while younger people (perhaps precisely because of their greater awareness of the perils of online voting) show more scepticism. In terms of both gender and education level, no significant differences emerge regarding the possibility of e-voting, while in terms of reasons for enrolling in AIRE, it is mainly expatriates and those enrolled by birth who are most keen on the proposal of electronic voting. It should be noted that even in this case it is mainly native-speaker Italians who are most in favour of the electronic voting solution.

Conversely, our respondents are split on the second proposal (regarding the possibility of voting only upon prior request): 48.3 per cent in favour and 51.7 per cent against. In this case, a gender gap is evident, in that male respondents appear to be more in favour than female respondents (51.3 per cent vs. 44.3 per cent) of the proposal of a right to vote abroad exercisable only upon request. While in terms of age no clear pattern emerges, it should be noted that more educated respondents are the ones least in favour of a right to vote that can be activated at the request of the person concerned, while those with middle or lower educational qualifications have a more positive opinion (52.2 per cent).

However, the largest discrepancies are found by taking into consideration the respondents’ country of birth. In fact, native-born Italians tend to be more supportive of the right to vote that can be activated on demand than those born abroad (49.1 per cent vs. 44.9 per cent); this result – as discussed above – may stem from a greater attachment to the former's country of origin.

Lastly, it is important to point out that it is mainly those respondents who define themselves as centre-left, in ideological terms, who are clearly more opposed to the hypothesis of vote on demand (56.5 per cent), while among those who declare themselves as centre or centre-right, opinions in favour of reforming the voting of Italians abroad prevail (58.4 per cent and 51.1 per cent, respectively).

Conclusion

By removing external voting hurdles and endowing its citizens abroad with parliamentary representation some two decades ago, Italy joined the growing list of countries that have experienced a wave of further democratisation (Caramani and Grotz Reference Caramani and Grotz2015). The road to external voting rights and political representation has been a notoriously difficult one. Ideological juxtapositions, controversies over constitutional legitimacy, and fears of vote rigging or tipping scenarios had delayed the process of reforming external voting procedures for decades. Once introduced, the Italian model of external voting has nonetheless allowed millions of Italians abroad to effectively engage in homeland elections and to vote in 18 external MPs to Rome's parliament (now 12, after a referendum to reduce the overall number of Italy's members of parliament by about one-third was passed in 2020). However, the shortcomings of the model – from vote mechanics to vote reliability to marginal political clout – have acted as a powerful deterrent to higher levels of electoral participation. One way to measure this is by examining the patterns and determinants of external voter turnout. The latter provides a telling clue, not so much when compared with the domestic turnout (external voters’ participation in elections is typically lower than in-country voters), but in terms of trend over time and across elections. What the Italian model of external voting has recorded over the last decade and a half is a constant and growing disaffection towards voting overall.

The purpose of this study was to expand our limited empirical knowledge of factors influencing Italian external turnout by utilising survey data collected among Italian voters living abroad, thus enhancing the scholarly discussion on transnational politics. Data from our online survey suggest that voting dynamics among citizens abroad resemble, to some extent, those occurring among voters in Italy, especially when it comes to socio-demographic variables (e.g. education). Conversely, noteworthy points of difference between the two cohorts (external and domestic) quickly emerge when other variables are taken into account. Unlike Italians in Italy, the external voters’ region of birth (i.e. their original geopolitical zone of reference) plays a negligible role in their propensity to vote. In other words, there is no ‘red regions’ factor, usually associated with a higher propensity to vote, present among voters abroad. On the other hand, characteristics that typically define Italian external voters, such as country of birth (whether born in Italy or abroad) and command of the Italian language (mother-tongue speakers vs. non-mother-tongue speakers) do really affect voter participation. In broad terms, those born in Italy and native speakers of Italian are more likely to vote than abstain from voting. When analysing the reasons for not voting, country of birth and Italian language skills are, again, important factors that may encourage or discourage voting, suggesting that hypotheses 1 and 2 could be confirmed. These factors are also useful tools when gauging the opinion about proposals such as the introduction of e-voting or the possibility of voting upon enrolment in the electoral roll, in place of the current system of default enrolment. External voters are likely to support voting for some reform proposals that may increase voter participation, such as e-voting, but remain ambivalent about others, suggesting that hypothesis 3 could be partially confirmed.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and valuable suggestions.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Simone Battiston is senior lecturer in history and politics in the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences at the Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne, Australia. His research examines different aspects of postwar Italian emigration, with a particular attention to the Australian context: external voting behaviour, history and memory of radical migrants, and migrant media history. His publications include Immigrants Turned Activists: Italians in 1970s Melbourne (Kibworth Beauchamp, UK: Troubador Publishing, 2012), Autopsia di un diritto politico: Il voto degli italiani all'estero nelle elezioni del 2018 (Turin: Accademia University Press, 2018, co-edited with S. Luconi) and Cittadini oltre confine: Storia, opinioni e rappresentanza degli italiani all'estero (Bologna: Il Mulino, 2022, co-edited with S. Luconi and M. Valbruzzi). He is an executive member of the Australian Migration History Network (AMHN). He also serves as book review editor for Altreitalie.

Stefano Luconi teaches US History in the Department of Historical and Geographical Sciences and the Ancient World at the University of Padua in Italy. He specialises in Italian migration to the United States with specific attention to Italian Americans’ political experience and transformations of their ethnic identity. On these topics he wrote From Paesani to White Ethnics: The Italian Experience in Philadelphia (Albany: SUNY Press, 2001) and The Italian-American Vote in Providence, Rhode Island, 1916–1948 (Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2004). His most recent volumes include La ‘nazione indispensabile’: Storia degli Stati Uniti dalle origini a Trump (Florence: Le Monnier, 2020) and L'anima nera degli Stati Uniti: Gli afro-americani e il difficile cammino verso l'eguaglianza, 1619-2023 (Padua: Cleup, 2023). He serves on the editorial boards of Altreitalie, Forum Italicum and The Italian American Review.

Marco Valbruzzi is Assistant Professor at the University of Naples Federico II and adjunct instructor at the Gonzaga University in Florence. His research interests focus on the transformations of both party organisations and party systems in Western Europe. He has co-edited (with R. Vignati) Il vicolo cieco: Le elezioni del 4 marzo 2018 (Bologna: Il Mulino, 2018) and, with S. Battiston and S. Luconi, Cittadini oltre confine: Storia, opinioni e rappresentanza degli italiani all'estero (Bologna: Il Mulino, 2022). His most recent book, with D. Campus, is Collective Leadership and Divided Power in West European Parties (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015). His works have appeared in European Journal of Political Research, Journal of Modern Italian Studies, Contemporary Italian Politics, South European Society & Politics, Italian Political Science Review, Revista Española de Ciencia Política and Romanian Political Science Review.