Abstract

This paper investigates the role of managerial biases in the real effects of limits to arbitrage. In a natural experiment setting with Regulation SHO, we find that the lifting of short sale constraints leads to a significant decrease in CEO confidence for pilot firms, and this result is more pronounced for pilot firms with financial constraints and stronger corporate governance. We further find that the real effects of Regulation SHO documented in the literature are primarily driven by CEOs with low confidence. Diffident CEOs of the pilot firms tend to decrease corporate investments, reduce earnings management, and improve social performance and employee relations following the removal of short sale constraints. Overall, we identify CEO confidence as a behavioral channel through which capital market frictions influence corporate decisions and CEO investments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The Regulation SHO was introduced by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) on July 28, 2004. Under this pilot program, the SEC randomly selected pilot stocks, which were composed of every third stock from the Russell 3000 constituents ranked by trading volume. These pilot stocks were exempt from two short-sale price tests: the uptick rule for NYSE-listed stocks and the bid test for NASDAQ National Market stocks. The pilot program was implemented from May 2, 2005, through July 7, 2007. See Securities Exchange Act Releases No. 34-50103 (https://www.sec.gov/rules/final/34-50103.pdf) and No. 50104 (https://www.sec.gov/rules/other/34-50104.htm) for more detail.

The experimental psychology literature finds significant variations in individuals’ confidence levels depending on task difficulty (Lichtenstein and Fischhoff 1977; Moore and Healy 2008), information (Oskamp 1965), and domains of the questions asked (Klayman et al. 1999). It is also found that overconfidence is affected by gender (Barber and Odean 2001) and history/culture (Koellinger et al. 2007).

The literature presents two scenarios on how removing short sale constraints leads to decreases in stock prices. First, given that the presence of short sale constraints leads to overpricing by hindering the incorporation of bad news into stock prices (Miller 1977; Hong and Stein 2003), lifting such restrictions provides a chance for the equity market to correct overpricing and improve price efficiency. Second, in contrast to these “desirable” price declines, there could be an unintended negative impact of removed short sale constraints. If short sale constraints play a role as a safeguard to protect firm value from bear raiders, who aim to push down a firm’s stock price even below its fundamental value through intensive shorting, removing short sale constraints will destabilize stock prices.

An alternative explanation for Hypothesis 1 from the perspective of firms’ boards would be that overconfident managers may be less likely to be selected as CEOs when short sale constraints are removed. This is somewhat consistent with a theoretical model developed by Goel and Thakor (2008). They claim that overconfident CEOs, due to their strong belief in the precision of their signal, tend to produce less accurate information. This leads the boards to avoid confident managers as CEOs following the enactment of the Sarbanes–Oxley Act, which imposes stringent penalties on misreporting. A similar logic applies to the case of Regulation SHO, where the boards may shift their preference towards less confident CEOs since the behavior of overconfident CEOs, such as overinvestment or production of less precise information, can be easily targeted by short sellers.

The 67% moneyness is calibrated with a risk aversion of three in a constant relative risk-aversion utility setting (Hall and Murphy 2002), and the original measure requires detailed information about CEO stock options, such as strike prices and remaining durations, which is not publicly available. Malmendier and Tate (2005, 2008) show that their results are robust to different thresholds in a range of 50–150%. Meanwhile, the main cutoff point used by Campbell et al. (2011) is 100%.

Malmendier and Tate (2005) first identify CEOs who at least twice during the sample period hold stock options that are at least 67% in-the-money during the fifth year after the option grant. From this subset of CEOs, they classify as overconfident those who fail to exercise the options during or before the fifth year at least twice during their tenure.

The confidence group includes “confident,” “confidence,” “overconfident,” “overconfidence,” “optimistic,” “optimism,” “overoptimistic,” and “overoptimism,” while the non-confidence group includes “pessimistic,” “pessimism,” “overpessimistic,” “reliable,” “cautious,” “conservative,” “practical,” “frugal,” and “steady”.

There are variations in using CEOs’ net stock purchases among existing studies. Campbell et al. (2011) identify overconfident CEOs if CEOs’ net purchases are in the top quintile of a given year’s net stock purchases and increase their ownership by at least 10% of the stock ownership. Kolasinski and Li (2013) classify CEOs as overconfident when they purchase shares and lose money from those purchases. This approach, however, might lead to misclassification since CEOs who indeed increase firm value could be classified as non-confident.

We exclude transactions related to option exercises and private transactions.

Starting with the annual constituent list of the 2004 Russell 3000 index, we exclude firms that were not listed on three stock exchanges (NYSE, AMEX, and NASDAQ) and that went public or had spinoffs after April 30, 2004. We thank FTSE Russell for providing us with the historical constituent lists of the Russell 3000 index.

Moreover, we are not able to look into daily or weekly changes in CEO confidence around the announcement due to the unavailability of high-frequency confidence data. See Sect. 6.4 for more detailed discussion of the announcement effect.

Our results remain intact when we include these firms.

The number of observations varies depending on the missing values of the variables for each analysis.

All variance inflation factors (VIFs) among the variables included in the baseline regression are also lower than 2.5, confirming the absence of multicollinearity in the sample.

Pilot is absorbed by firm fixed effects, and During and Post are subsumed by year fixed effects.

Given the possibility that the timing of the stock option exercise could be affected by market conditions, the inclusion of bullish years, such as 2005 and 2006, in the pilot period might result in low levels of CEO confidence. To verify that our main findings are not driven by changes in CEOs’ stock option exercise behavior depending on market conditions, we include year fixed effects in Eq. (2), which control for time trends in CEO confidence and transitory factors such as macroeconomic conditions. In addition, we perform robustness tests in Sect. 6.1 using alternative, non-option-based confidence measures, such as the measures based on media and insider net purchases, respectively. The results remain robust to the use of year fixed effects and alternative confidence measures. We perform an additional test to see if reduced CEO confidence during the pilot period is attributed to positive market conditions in 2005 and 2006. For this analysis, two variables are added to Eq. (2): (1) Boom, which is a dummy variable for the years 2005 and 2006, and (2) Boom × Treatment, which is the interaction term between Boom and Treatment. The coefficient on Treatment is significantly negative, while both coefficients on Boom and Boom × Treatment are not statistically significant. The results demonstrate that our finding of decreased confidence during the pilot period is not the manifestation of a significant change in CEOs’ stock option exercise behavior due to favorable market conditions.

0.061/0.45 ≈ 0.136.

When we add board-specific variables to the baseline regressions in columns (1)–(5) of Table 2, the coefficient on board size (Bsize) is in general positive but statistically insignificant, while the coefficient on the percentage of independent board directors (Pind) is significantly negative. The results suggest that CEO confidence decreases with strong corporate governance proxied by more independent board directors or small board size, although the results are mixed in terms of sign and significance.

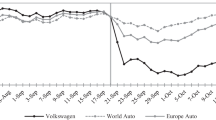

Grullon et al. (2015) find decreases in pilot firms’ cumulative abnormal returns around the announcement of the pilot program, especially for small firms.

The results are unaltered when we repeat the tests with shorter-term returns, such as 20- or 30-day CARs ([ −10, + 10] and [ −10, + 20]), or with alternative benchmark returns such as CRSP equal- and value-weighted returns.

The DGTW benchmarks are available via http://terpconnect.umd.edu/~wermers/ftpsite/Dgtw/coverpage.htm.

Considering the potential impact of the 2007–2008 financial crisis on CEO confidence, we repeat the analysis with Crisis, which is an indicator variable for the years 2007 and 2008, and Post-treatment × Crisis, which is a three-way interaction term between Pilot, Post, and Crisis. As a result, the negative coefficient on Treatment remains robust after controlling for the crisis, while the coefficient on Post-treatment × Crisis is not statistically significant. This shows that our main results are not contaminated by the inclusion of the crisis period.

We define small board size as a proxy for strong corporate governance, since many prior studies document that board size is negatively associated with firm performance (Lipton and Lorsch 1992; Jensen 1993; Yermack 1996; Eisenberg et al. 1998). However, the results with board size should be interpreted with caution, because there is no consensus on the optimal board size. Some studies argue that the relation between board size and firm performance is sensitive to test methods as well as measures (Mak and Li 2001; Bhagat and Black 2002).

To avoid look-ahead bias, we use cumulative ranks up to year t of the pilot period. For 2006 data, for example, \({HtoL}_{i,t}\) (\({LtoH}_{i,t}\)) is an indicator that equals one when firm i is in the top (bottom) tercile of CEO confidence during 2001, 2002, and 2003, and in the bottom (top) tercile during 2005 and 2006, and zero otherwise. The coefficients on \({HtoL}_{i,t}\) and \({LtoH}_{i,t}\) are subsumed by firm fixed effects in our estimation.

We further examine if such decreased investments driven by underconfident CEOs reinforce firm stability proxied by ROA and TobinQ during the post-pilot period. For this analysis, we sort the data into 2 × 2 portfolios based on CEO confidence and corporate investments during the pilot period and report the means of firm stability estimates over the post-pilot period for each double-sorted group. In unreported results, we do not find evidence that reduced investments driven by low levels of confidence during the pilot period improve firm stability during the post-pilot period.

We use year fixed effects to control for time-varying differences in Tables 4 and 5. When we repeat the analysis with time-varying effects allowed, the investment results in Table 4 remain intact in terms of magnitude and significance. The earnings management results in Table 5 are also robust in terms of magnitude but show less significance. These results are available upon request.

As explained in Sect. 4.1, the original Holder67 measure requires data detailing strike prices and remaining option durations. We employ a modified version of Holder67 instead, which can be computed from the ExecuComp data.

Malmendier et al. (2011) consider CEOs overconfident if the confidence level exceeds the 67% threshold with a remaining duration of five years. For our robustness tests, we estimate Holder67 as an indicator that equals one if CEO confidence exceeds 67% for two consecutive years, and zero otherwise. The results are unchanged.

Changes in CEO confidence would depend on the relative magnitudes of changes in the average value per option and the stock price.

We also generate an indicator that equals one if the net number of confidence articles is positive, and zero otherwise. In unreported results, the coefficient on Treatment is negative but statistically insignificant.

The test results could be spurious because the pilot program was announced in July 2004.

References

Adams R, Keloharju M, Knüpfer S (2018) Are CEOs born leaders? Lessons from traits of a million individuals. J Financ Econ 130:392–408

Ahmed AS, Duellman S (2013) Managerial overconfidence and accounting conservatism. J Account Res 51:1–30

Banerjee S, Humphery-Jenner M, Nanda VK (2015) Restraining overconfident CEOs through improved governance: evidence from the Sarbanes-Oxley Act. Rev Financ Stud 28:2812–2858

Banerjee S, Dai L, Humphery-Jenner M, Nanda VK (2020) Governance, board inattention, and the appointment of overconfident CEOs. J Bank Financ 113:105733

Barber BM, Odean T (2001) Boys will be boys: gender, overconfidence, and common stock investment. Q J Econ 116:261–292

Battalio R, Schultz P (2006) Options and the bubble. J Financ 61:2071–2102

Battalio R, Mehran H, Schultz P (2012) Market declines: what is accomplished by banning short-selling? Curr Issues Econ Financ 18:1–7

Bebchuk LA, Cohen A, Ferrell A (2009) What matters in corporate governance? Rev Financ Stud 22:783–827

Beber A, Pagano M (2013) Short-selling bans around the world: evidence from the 2007–09 crisis. J Financ 68:343–381

Ben-David I, Graham JR, Harvey CR (2013) Managerial miscalibration. Q J Econ 128:1547–1584

Ben-David I, Graham JR, Harvey CR (2007) Managerial overconfidence and corporate policies. NBER Working Paper No. 13711.

Bhagat S, Black B (2002) The non-correlation between board independence and long-term performance. J Corp Law 27:231–243

Billett MT, Qian Y (2008) Are overconfident CEOs born or made? Evidence of self-attribution bias from frequent acquirers. Manage Sci 54:1037–1051

Blejer MI, Feldman EV, Feltenstein A (1997) Exogenous shocks, deposit runs, and bank soundness: a macroeconomic framework. IMF Working Paper.

Boehmer E, Jones CM, Zhang X (2013) Shackling short sellers: the 2008 shorting ban. Rev Financ Stud 26:1363–1400

Bouwman C (2014) Managerial optimism and earnings smoothing. J Bank Financ 41:283–303

Brockman P, Luo J, Xu L (2020) The impact of short-selling pressure on corporate employee relations. J Corp Financ 64:101677

Cadman BD, Rusticus TO, Sunder J (2013) Stock option grant vesting terms: economic and financial reporting determinants. Rev Acc Stud 18:1159–1190

Campbell TC, Gallmeyer M, Johnson SA, Rutherford J, Stanley BW (2011) CEO optimism and force turnover. J Financ Econ 101:695–712

Chen Y, Ofosu E, Veeraraghavan M, Zolotoy L (2023) Does CEO overconfidence affect workplace safety? J Corp Financ 82:102430

Chu Y, Hirshleifer DA, Ma L (2020) The causal effect of limits to arbitrage on asset pricing anomalies. J Financ 75:2631–2672

Cochran PL, Wood RA (1984) Corporate social responsibility and financial performance. Acad Manag J 27:42–56

Crane AD, Crotty K, Michenaud S, Naranjo PL (2019) The causal effects of short-selling bans: evidence from eligibility thresholds. Rev Asset Pric Stud 9:137–170

Daniel K, Grinblatt M, Titman S, Wermers R (1997) Measuring mutual fund performance with characteristic-based benchmarks. J Financ 52:1035–1058

Daniel K, Hirshleifer D, Subrahmanyam A (1998) Investor psychology and security market under- and overreactions. J Financ 53:1839–1885

De Angelis D, Grullon G, Michenaud S (2017) The effects of short-selling threats on incentive contracts: evidence from an experiment. Rev Financ Stud 30:1627–1659

Dechow PM, Sloan RG, Sweeney AP (1995) Detecting earnings management. Account Rev 70:193–225

Deng X, Gupta VK, Lipson ML, Mortal S (2022) Short-sale constraints and corporate investment. J Financ Quant Anal. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022109022000849

Diether K, Lee K, Werner L (2009) It’s SHO time! Short-sale price tests and market quality. J Financ 64:37–73

Eisenberg T, Sundgren S, Wells M (1998) Larger board size and decreasing firm value in small firms. J Financ Econ 48:35–54

Fang VW, Huang AH, Karpoff JM (2016) Short selling and earnings management: a controlled experiment. J Financ 71:1251–1294

Gao L, He J, Wu J (2022) Standing out from the crowd via CSR engagement: evidence from non-fundamental-driven price pressure. J Finan Quant Anal. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022109023000686

Gervais S, Odean T (2001) Learning to be overconfident. Rev Financ Stud 14:1–27

Gilchrist S, Himmelberg C, Huberman G (2005) Do stock price bubbles influence corporate investment? J Monet Econ 52:805–827

Goel A, Thakor AV (2008) Overconfidence, CEO selection, and corporate governance. J Financ 63:2737–2784

Gompers PA, Ishii JL, Metrick A (2003) Corporate governance and equity prices. Q J Econ 118:107–155

Graham JR, Harvey CR, Puri M (2013) Managerial attitudes and corporate actions. J Financ Econ 109:103–121

Grullon G, Michenaud S, Weston JP (2015) The real effects of short-selling constraints. Rev Financ Stud 28:1737–1767

Hall BJ, Murphy KJ (2000) Optimal exercise prices for executive stock options. Am Econ Rev 90:209–214

Hall BJ, Murphy KJ (2002) Stock options for undiversified executives. J Account Econ 33:3–42

Harrison JM, Kreps DM (1978) Speculative investor behavior in a stock market with heterogeneous expectations. Q J Econ 92:323–336

He J, Tian X (2016) Do short sellers exacerbate or mitigate managerial myopia? Evidence from patenting activities. Working Paper.

Hilary G, Menzly L (2006) Does past success lead analysts to become overconfident? Manage Sci 52:489–500

Hirshleifer D, Low A, Teoh SH (2012) Are overconfident CEOs better innovators? J Financ 67:1457–1498

Hong H, Stein JC (2003) Difference of opinion, short-sales constraints and market crashes. Rev Financ Stud 16:487–525

Hribar P, Yang H (2016) CEO overconfidence and management forecasting. Contemp Account Res 33:204–227

Hsieh TS, Bedard JC, Johnstone KM (2014) CEO overconfidence and earnings management during shifting regulatory regimes. J Bus Financ Acc 41:1243–1268

Humphery-Jenner M, Lisic LL, Nanda V, Silveri SD (2016) Executive overconfidence and compensation structure. J Financ Econ 119:533–558

Jensen MC (1993) The modern industrial revolution, exit, and the failure of internal control systems. J Financ 48:831–880

Jones J (1991) Earnings management during import relief investigations. J Account Res 29:193–228

Jones C, Lamont O (2002) Short sales constraints and stock returns. J Financ Econ 66:207–239

Kaplan SN, Zingales L (1997) Do investment-cash flow sensitivities provide useful measures of financing constraints? Q J Econ 112:169–215

Klayman J, Soll JB, Gonzalez-Vallejo C, Barlas S (1999) Overconfidence: it depends on how, what, and whom you ask. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 79:216–247

Koellinger P, Minniti M, Schade C (2007) “I think I can, I think I can”: overconfidence and entrepreneurial behavior. J Econ Psychol 28:502–527

Kolasinski AC, Li X (2013) Can strong boards and trading their own firm’s stock help CEOs make better decisions? Evidence from acquisitions by overconfident CEOs. J Financ Quant Anal 48:1173–1206

Lambert RA, Larcker DF, Verrecchia RE (1991) Portfolio considerations in valuing executive stock options. J Account Res 29:129–149

Lee JM, Hwang BH, Chen H (2017) Are founder CEOs more overconfident than professional CEOs? Evidence from S&P 1500 companies. Strateg Manag J 38:751–769

Lee JM, Park JC, Chen G (2023) A cognitive perspective on real options investment: CEO overconfidence. Strateg Manag J 44:1084–1110

Lichtenstein S, Fischhoff B (1977) Do those who know more also know more about how much they know? Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 20:159–183

Lipton M, Lorsch J (1992) A modest proposal for improved corporate governance. Bus Lawyer 48:59–77

Mak YT, Li Y (2001) Determinants of corporate ownership and board structure: evidence from Singapore. J Corp Finan 7:235–256

Malmendier U, Nagel S (2011) Depression babies: do macroeconomic experiences affect risk taking? Q J Econ 126:373–416

Malmendier U, Tate M (2005) CEO overconfidence and corporate investment. J Financ 60:2661–2700

Malmendier U, Tate M (2008) Who makes acquisitions? CEO overconfidence and the market’s reaction. J Financ Econ 89:20–43

Malmendier U, Tate M, Yan J (2011) Overconfidence and early-life experiences: the effect of managerial traits on corporate financial policies. J Financ 66:1687–1733

Marsh IW, Payne R (2012) Banning short sales and market quality: the UK’s experience. J Bank Financ 36:1975–1986

Massa M, Zhang B, Zhang H (2015) The invisible hand of short selling: does short selling discipline earnings management? Rev Financ Stud 28:1701–1736

McCarthy S, Oliver B, Song S (2017) Corporate social responsibility and CEO confidence. J Bank Financ 75:280–291

McWilliams A, Siegel D (2000) Corporate social responsibility and financial performance: correlation or misspecification? Strateg Manag J 21:603–609

Miller E (1977) Risk, uncertainty, and divergence of opinion. J Financ 32:1151–1168

Moore DA, Healy PJ (2008) The trouble with overconfidence. Psychol Rev 115:502–517

Murphy KJ (1999) Executive compensation. In: Ashenfelter O, Card D (eds) Handbook of labor economics, vol 3. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 2485–2563

Ofek E, Richardson M (2003) DotCom mania: the rise and fall of internet stock prices. J Financ 58:1113–1138

Oskamp S (1965) Overconfidence in case-study judgments. J Consult Psychol 29:261–265

Praet P, Vuchelen J (1988) Exogenous shocks and consumer confidence in four major European countries. Appl Econ 20:561–567

Roll R (1986) The hubris hypothesis of corporate takeovers. J Bus 59:197–216

Schrand CM, Zechman S (2012) Executive overconfidence and the slippery slope to financial misreporting. J Account Econ 53:311–329

Securities and Exchange Commission’s Office of Economic Analysis (2007) Economic analysis of the short sale price restrictions under the Regulation SHO pilot.

Stambaugh RF, Yu J, Yuan Y (2012) The short of it: investor sentiment and anomalies. J Financ Econ 104:288–302

Teoh SH, Welch I, Wazzan CP (1999) The effect of socially activist investment policies on the financial markets: evidence from the South African Boycott. J Bus 72:35–89

Whited TM, Wu G (2006) Financial constraints risk. Rev Financ Stud 19:531–559

Yermack D (1996) Higher market valuation of companies with a small board of directors. J Financ Econ 40:185–211

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors did not receive any funding for this study and have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We thank the editor Cheng-Few Lee and two anonymous referees for their useful comments and suggestions. We are also grateful for helpful comments from Xiaoting Hao, Steven Irlbeck, Jung Chul Park, Anjan Thakor, Chi Zhang, Linghui Zhou, and participants of the 2019 Eastern Finance Association Annual Meeting and the 2019 Financial Management Association Annual Meeting.

Appendices

Appendix

Variable definitions

Variables | Definition |

|---|---|

CEO confidence measures | |

Conf | The average value per option of CEOs’ vested in-the-money options (the value of all unexercised exercisable options (Execucomp: opt_unex_exer_est_val) divided by the number of options (Execucomp: opt_unex_exer_num)), scaled by the stock price at the end of a fiscal year (Compustat: prcc_f). See Banerjee et al. (2015) for more detail |

Conf_h | A dummy variable that equals one if a firm is in the top tercile of CEO confidence in a given year, and zero otherwise |

Conf_hʹ | A dummy variable that equals one if the confidence level is higher than 100%, and zero otherwise |

Conf_l | A dummy variable that equals one if a firm is in the bottom tercile of CEO confidence in a given year, and zero otherwise |

Conf_lʹ | A dummy variable that equals one if the confidence level is lower than 30% and zero, otherwise |

Holder30 | An indicator that equals one if a CEO’s confidence level equals at least 30%, and zero otherwise. See Campbell et al. (2011) and Malmendier et al. (2011) |

Holder67 | An indicator that equals one if a CEO’s confidence level equals at least 67%, and zero otherwise |

Holder100 | An indicator that equals one if a CEO’s confidence level equals at least 100%, and zero otherwise |

HtoL | An indicator that equals one if a firm is in the top tercile of CEO confidence during the pre-pilot period and in the bottom tercile up to year t of the pilot period, and zero otherwise |

HtoLʹ | An indicator that equals one if the confidence level is higher than 100% during the pre-pilot period and lower than 30% up to year t of the pilot period, and zero otherwise |

LtoH | An indicator that equals one if a firm is in the bottom tercile of CEO confidence during the pre-pilot period and in the top tercile up to year t of the pilot period, and zero otherwise |

LtoHʹ | An indicator that equals one if the confidence level is lower than 30% during the pre-pilot period and higher than 100% up to year t of the pilot period, and zero otherwise |

News | The net number of confidence news articles calculated as the number of articles containing confidence words minus the number of articles containing non-confidence words. See Sect. 4.1 for more detail |

∆News | Annual changes in the net number of confidence news articles |

NPR | Net purchase ratio calculated as the difference between the number of shares purchased by a given CEO and the number of shares sold, scaled by the sum of the shares traded by the CEO each year |

Firm and CEO characteristics | |

∆AT | Changes in total assets scaled by total assets at the beginning of the year |

Bsize | Board size measured as the natural logarithm of the total number of directors on the board |

CAPEX | Capital expenditures divided by year-end total assets |

CAPXRD | The sum of capital expenditures and R&D expenditures scaled by year-end total assets |

CF | Sum of net income before extraordinary items and depreciation and amortization expenses scaled by year-end total assets |

CEO_age | CEO age |

CEO_gen | An indicator that equals one if a CEO is male and zero, otherwise |

CEO_ten | CEO tenure measured by the number of years a CEO has held the current position |

CSR | The sum of net CSR scores in six categories (community, environment, diversity, employee relations, human rights, and product). The net CSR scores are calculated as the total number of strengths minus the total number of concerns in each category |

DA | Discretionary accruals calculated based on the Jones (1991) model. We first estimate the following regression model: \({\text{TAQ}}_{{\text{t}}} = {\upalpha } + {\upbeta }_{1} \times \frac{1}{{{\text{TAQ}}_{{{\text{t}} - 1}} }} + {\upbeta }_{2} \times \Delta {\text{SALES}}_{{\text{t}}} + {\upbeta }_{3} \times {\text{PPE}}_{{\text{t}}} + \varepsilon_{t}\) where \({\text{TAQ}}_{{\text{t}}} = \left( {\Delta {\text{current assets}} - \Delta {\text{current liabilities}} - \Delta {\text{cash and cash equivalents}} - \Delta {\text{short}}{-}{\text{term debt}} - {\text{depreciation and amortization}}} \right)/{\text{total assets}}\). Discretionary accruals are residual values obtained from the estimation |

During | A dummy variable that equals one if the fiscal year is in the durg-pilot period (2005–2007), and zero otherwise |

E-Index | Bebchuk et al. (2009) entrenchment index constructed based on six provisions |

G-Index | Gompers et al. (2003) governance index constructed based on 24 governance provisions |

KZ Index | Kaplan and Zingales (KZ) financial constraints index calculated as -1.002 × Cash flow + 0.283 × Tobin’s Q + 3.189 × Leverage − 39.368 × Dividends − 1.315 × Cash holdings, where cash flows, dividends, and cash holdings are scaled by property, plant, and equipment (PPE) at the beginning of the fiscal year. See Kaplan and Zingales (1997) for more detail |

LCAR | An indicator that equals one if a firm is in the bottom CAR portfolio, and zero otherwise. For each industry, we sort data into terciles based on cumulative abnormal returns from day t-10 to day t + 120 around July 28, 2004, when the pilot program was announced. The industry is identified by the two-digit SIC code, and the abnormal return is computed as the difference between raw return and Daniel et al. (1997) benchmark return |

Leverage | Sum of long-term debt and debt in current liabilities scaled by the sum of long-term debt, debt in current liabilities, and total equity |

Market-to-Book | Market value of assets divided by the book value of assets. The market value of assets equals the sum of the market value of equity and the book value of total assets minus the book value of equity minus deferred tax liabilities, scaled by the book value of total assets |

MDA | Discretionary accruals calculated based on the modified Jones (1991) model (Dechow et al. 1995). These are residual values obtained from the estimation of the following regression model: \({\mathrm{TAQ}}_{\mathrm{t}}=\mathrm{\alpha }+{\upbeta }_{1}\times \frac{1}{{\mathrm{TAQ}}_{\mathrm{t}-1}}+{\upbeta }_{2}\times \left(\Delta {\mathrm{SALES}}_{\mathrm{t}}-\Delta {\mathrm{REC}}_{\mathrm{t}}\right)+{\upbeta }_{3}\times {\mathrm{PPE}}_{\mathrm{t}}+{\varepsilon }_{t}\) where \(\Delta {\mathrm{REC}}_{\mathrm{t}}\) is a change in receivables scaled by total assets |

Pilot | A dummy variable that equals one if a firm’s stock is selected as a pilot stock for Regulation SHO, and zero otherwise |

Pind | Percentage of independent directors on the board of directors |

Post | A dummy variable that equals one if the fiscal year is in the post-pilot period (2008–2010), and zero otherwise |

Post-treatment | A dummy variable that equals one if a given firm is listed as a pilot firm and its fiscal year is in the post-pilot period (2008–2010), and zero otherwise |

RD | Research and development expenditures scaled by year-end total assets. This is set to zero if missing |

Ret | Holding period return for a given year |

ROA | Operating income before depreciation and amortization divided by year-end total assets |

Size | Natural logarithm of total assets at the end of a fiscal year |

TobinQ | The ratio of market value of assets to book value of total assets |

Treatment | A dummy variable that equals one if a given firm is listed as a pilot firm and its fiscal year is in the during-pilot period (2005–2007), and zero otherwise |

Volatility | The standard deviation of daily returns for a given year |

WW Index | Whited and Wu (WW) financial constraints index calculated as − 0.091 × Cash flow − 0.062 × (indicator equal to one if the sum of common dividends and preferred dividends is positive, and zero otherwise) + 0.021 × Leverage − 0.044 × ln(total assets) + 0.102 × average industry sales growth estimated for each 3-digit SIC industry per year − 0.035 × Sales growth. See Whited and Wu (2006) for more detail |

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Jang, J., Lee, E. CEO confidence matters: the real effects of short sale constraints revisited. Rev Quant Finan Acc 62, 603–636 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-023-01215-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-023-01215-7

Keywords

- CEO confidence

- Short sale constraints

- Corporate investment

- Earnings management

- Corporate social responsibility