Abstract

COVID-19 caused a great burden on the healthcare system and led to lockdown measures across the globe. These measures are likely to influence crime rates, but a comprehensive overview on the impact of COVID-19 on crime rates is lacking. The aim of the current study was to systematically review evidence on the impact of COVID-19 measures on crime rates across the globe. We conducted a systematic search in several databases to identify eligible studies up until 6–12-2021. A total of 46 studies were identified, reporting on 99 crime rates about robberies (n = 12), property crime (n = 15), drug crime (n = 5), fraud (n = 5), physical violence (n = 15), sexual violence (n = 11), homicides (n = 12), cybercrime (n = 3), domestic violence (n = 3), intimate partner violence (n = 14), and other crimes (n = 4). Overall, studies showed that most types of crime temporarily declined during COVID-19 measures. Homicides and cybercrime were an exception to this rule and did not show significant changes following COVID-19 restrictions. Studies on domestic violence often found increased crime rates, and this was particularly true for studies based on call data rather than crime records. Studies on intimate partner violence reported mixed results. We found an immediate impact of COVID-19 restrictions on almost all crime rates except for homicides, cybercrimes and intimate partner violence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the spring of 2020, the Coronavirus Disease-2019 (COVID-19) reached most countries across the globe and caused a great burden on society, in particular on the healthcare system and economy. To reduce the spread of the virus and its strain on the healthcare system, many governments quickly imposed (lockdown) measures including stay-at-home orders, travel bans, physical distancing, closed schools, and restricted private and public gatherings. These measures proved to be effective in slowing down the virus (Talic et al., 2021), but also had a huge impact on daily life (Helsingen et al., 2020; Marroquin et al., 2020; O'Donnell & Greene, 2021; Olff et al., 2021; Tull et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2022).

Early on, reviews suggested that COVID-19 measures could increase specific crime rates such as domestic violence and intimate partner violence (e.g., Bradbury-Jones & Isham, 2020; Ertan et al., 2020; Kaukinen, 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic and restrictions heightened risk factors for domestic violence and intimate partner violence such as unemployment, financial insecurity, and stress (Bradbury-Jones & Isham, 2020; Morgan & Boxall, 2020). Moreover, since people were confined to their home, it might be difficult to seek help or for others to notice the abuse taking place. These heightened risk factors are also known to influence crimes such as property crime (Lin, 2008; Speziale, 2014). On the other hand, the COVID-19 restrictions have been shown to reduce daily movement and increase time spent at home (e.g., Borkowski et al., 2021; Cheung & Gunby, 2022), both potentially lowering the opportunity for crimes such as theft and robbery (Caminha et al., 2017; Cheung & Gunby, 2022).

There are at least three crime related theories that are relevant in the context of COVID-19. Firstly, routine activities theory explains crimes by a motivated offender, suitable target and lack of capable guardianship and stresses that crime is influenced by routine activities such as work, family and social life (Cohen & Felson, 1979). Since COVID-19 restrictions limit (social) interactions thereby reducing capable guardianship in a family setting, one might expect an increase in crimes committed in family settings while crimes in public settings might decrease related to the reduced interactions in public settings.. Moreover, since COVID-19 restrictions reduce mobility and increase the use of online communication, suitable targets are increasingly found online rather than offline and one might expect an increase in online and a decrease in offline crimes.. Secondly, rational choice theory explains crimes by information which leads to beliefs about opportunities and outcomes of crimes, resulting in a rational choice to commit crimes (Karstedt, 1994). According to this theory, crimes with a high reward and low perceived risk and effort such as non-residential burglaries (i.e. burglaries of buildings not used for people to live in) will increase during COVID-19 restrictions. Moreover, the social restriction measures might have led to a lower perceived risk of domestic violence since it was more difficult for the victim to seek help without the perpetrator knowing. This might result in increased domestic violence.

Thirdly, the general strain theory posits that people commit crimes to alleviate strain and stress (Agnew, 1992). It distinguishes objective strain (generally experienced as stressful such hospitalization due to COVID-19) from subjective strain (personally stressful such as stay-at-home orders which might be extremely stressful for some but less stressful for others). General strain theory also distinguishes three types of events eliciting strain: introduction of negative stimuli, removal of positive stimuli and inability to attain one’s goals. It emphasizes the role of coping with strain (where criminal behaviour can be considered a behavioural maladaptive coping strategy) and similar to rational choice theory the role of costs of crime. Following this theory, one would expect that COVID-19 and COVID-19 restrictions (e.g., lockdowns) lead to increased strain especially related to inability to attain goals (e.g., a bartender might not be able to attain his/her goal of supporting his/her family due to loss of work) and reduced coping capabilities (e.g., less social support due to lockdown) and therefore increased crime specifically crime with low perceived costs such as theft, non-residential burglaries and domestic violence. (Eriksson & Mazerolle, 2013). Generally, routine activities theory and – to some extend—rational choice theory stress the importance of opportunity to commit crimes which is reduced for most crimes due to COVID-19 restrictions, while general strain theory emphasises individual predictors (strain) of crime which are likely increased due to COVID-19 (restrictions). Hence, based on routine activities and rational choice theory COVID-19 restrictions are expected to reduce most crime rates except for online crimes and domestic violence which might both increase due to increased opportunity. Based on general strain theory, we expect an increase in crime rates with low costs such as domestic violence driven by increased strain.

Many studies across the globe have evaluated the impact of COVID-19 (measures) including lockdowns, social distancing, stay-at-home orders, working from home orders and restricted gatherings on crime rates and patterns. Moreover, several reviews on the impact of COVID-19 on specific crime rates have been published (Kourti et al., 2023; McNeil et al., 2023; Regalado et al., 2022). These reviews increased awareness into the potential impact of COVID-19 measures on crime rates. However, they often did not include systematic search strategies and only focused on a small subset of studies (e.g., at the start of the pandemic or one specific crime rate). Hence, most crime rates have not been systematically reviewed, precluding overall conclusions about crime rates and patterns. Moreover, it has not been evaluated whether change in crime rates due to COVID-19 differs based on study characteristics such as country or data source. If COVID-19 measures truly impact crime rates for example by reducing daily movements, we would expect a larger impact on crime rates in countries with more stringent COVID-19 measures (and thus more reduced daily movement) compared to countries with less stringent measures. Additionally, some data sources like police records might be influenced by limited resources to record crime rates due to the enforcement of (lockdown) measures and therefore underrepresent crime rates (White & Fradella, 2020). Other data sources like hospital data usually assess trauma as a proportion of all trauma cases in a specific period and might overrepresent crime rates since overall trauma cases seem to have been decreased during COVID-19 (Pikoulis et al., 2020).

In the current study, we systematically review evidence for the impact of COVID-19 on crime rates. Specifically, we review the impact on robberies, property crime, drug crime, fraud, physical violence, sexual violence, homicides, cybercrime, domestic violence, IPV, COVID-19-related violence, nature crime, elderly abuse, and traffic crime. We evaluate the impact of COVID-19 in three ways. Firstly, we evaluate changes in crime rates during COVID-19 in general compared to pre-COVID times. Secondly, we evaluate changes in crime rates due to imposing restrictions during COVID-19 such as stay-at-home orders, travel bans, social distancing etc. Thirdly, we evaluate changes in crime rates due to relaxing COVID-19 restrictions.

Method

Search Strategies

We conducted systematic searches up to the 6th of December 2021 in PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, Emcare, PsycINFO, Academic Search premier, Criminal Justice Abstracts, WHO Covid Database, COVID-19 Evidence, Social Services Abstracts and Sociological Abstracts. The searches were based on (MeSH) terms for: a) crimes, b) COVID-19 and c) COVID-19 measures. See Appendix 1 for the full search strategy. We included both individual studies and reviews, because we adopted a umbrella review approach when multiple reviews were published about a crime rate. Titles and abstracts of identified studies were screened independently by two authors (CH and BW) for inclusion and exclusion criteria using web-tool Rayyan (Ouzzani et al., 2016) until the researchers reached satisfactory agreement (Cohen’s Kappa > 0.7). Discrepancies were resolved through discussion. For the first 250 titles and abstracts, interrater reliability was not satisfactory (Cohen’s Kappa = 0.67, agreement = 83%). After discussing discrepancies and reaching consensus on the screening procedure, the interrater reliability was satisfactory for the following 500 titles and abstracts (Cohen’s Kappa = 0.73, agreement = 90%). The remaining titles and abstracts were screened by one of the two authors. Thereafter, full-texts of eligible studies were screened by two authors with the same procedure. The interrater reliability for the first 90 full-texts was not satisfactory (Cohen’s Kappa = 0.69, agreement = 85%), but it was for the next 90 full-texts (Cohen’s Kappa = 0.89, agreement = 95%). The remaining full-texts were screened by one of the two authors. The design of this review was pre-registered at Prospero (ID number CRD42021288748).

Inclusion Criteria

We included individual studies, systematic reviews and meta-analyses including individual studies with data collected during COVID-19 which a) measured a change in crime rate during COVID-19 (so included a comparison pre-COVID) b) included at least 25 participants; c) were written in English, Dutch, French, German, or Spanish. When we identified at least two systematic reviews/meta-analyses on a specific crime rate, we excluded individual papers and used an umbrella review approach to summarize the reviews and meta-analyses. We excluded non-systematic reviews and we only included one study per crime rate per data source from a specific city. We first prioritized studies which reported about multiple cities over studies reporting about a single city and secondly we prioritized studies including most recent data.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Data was extracted by one author (BW) and checked by another author (CH). Study quality was assessed by the two authors independently using the NIH risk of bias tool for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies and the NIH risk of bias tool for systematic reviews and meta-analyses depending on the study design (NIH, 2013). Studies were rated poor, fair, or good. Discrepancies between researchers were resolved through discussion. We extracted information about the study (design, population, location, inclusion and exclusion criteria, data source, sample size, and measurements, whether comparisons pre-post COVID-19 and/or pre-post COVID-19 lockdown were made, period of data collection, and measurements), study sample demographics (gender and age), crime (type of crime) and analysis (type of analysis, covariates, and outcomes). With regard to the data source, we included data from crime-records (usually provided by the police), hospital data about the type of violence which induced the injury (usually based on electronic health records), emergency call data for help (usually to 911, the police or another organization involved in domestic violence), and autopsy reports.

We categorized the outcomes of the analysis into three categories: COVID-19 (measures) led to a significant decrease in crime rates (-), had no significant impact on crime rates (-/ +), or led to a significant increase in crime rates ( +). We set p-value for significance at p < 0.05. When a single study reported on crime rates in multiple cities, we categorized the overall outcome of a study as a significant increase or decrease when at least 50% of the cities show an effect in this direction, and a maximum of 25% of the cities show an effect in the opposite direction. Otherwise, the results were categorized as not having significant impact on crime rates. When a single study reported the impact of COVID-19 (measures) on crime rates for several months into the lockdown separately, we categorized the overall outcome as a significant increase or decrease when at least 50% of the months showed an effect in this direction and a maximum of 25% of the months showed an effect in the opposite direction. Otherwise, the results were categorized as not having significant impact on crime rates. When a single study reported separately about an immediate impact of COVID-19 (measures) followed by a trend over time, we used both types of information and categorized the overall outcome as a significant increase or decrease when at least 50% of the data demonstrated an effect in this direction and a maximum of 25% of the data demonstrated an effect in the opposite direction. Otherwise, the results were categorized as not having significant impact on crime rates.

Results

Study Selection

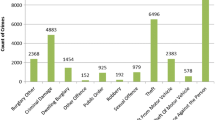

We identified 4,799 studies (1,726 after removal of duplicates; see Fig. 1 for flowdiagram). We excluded 1,318 records based on title and abstract screening. We could not retrieve 11 reports and thus assessed 397 full-texts for eligibility. Of these, 351 full-texts were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. The remaining 46 studies were included in this review. For domestic violence we found several systematic reviews and therefore we excluded individual studies on domestic violence from the current review. For physical violence we found one systematic review using hospital data and therefore individual studies using hospital data for physical violence were excluded from the current review. For all other types of crimes, we did not identify multiple systematic reviews and therefore reviewed individual studies. See Table 1 for study characteristics and outcomes of all included studies. Note that there is some overlap between crimes (i.e., sexual assault of an intimate partner both meets criteria for intimate partner violence and sexual violence). Figure 2 summarizes the findings on changes in crimes rates after COVID-19 restrictions are imposed.

Robberies

Nine individual studies on robberies (e.g., street robberies, vehicle robberies, robbery against residence), reported on 11 results from seven countries based on crime records, and a large study reported on results from around the world (24 cities). Most studies reported on data from western countries (8 results) and most studies corrected for seasonal components (7 results). The results from all studies showed a significant decrease in robberies due to COVID-19 restrictions (n = 12). The global study found that this decrease was related to the stringency of the restrictions. Another study found that relaxing restrictions led to increases in robberies, while one study found no relationship between relaxing restrictions and robberies.

Property Crime

Twelve individual studies on property crime (e.g., burglaries, theft of vehicle, theft from person, shoplifting) reported on 14 results from 10 countries based on crime records, and a large study reported on results from around the world (20 cities). Most studies reported on data from western countries (10 results) and corrected for seasonal components (11 results). Findings on the relationship between COVID-19 in general and property crime were mixed for most studies (n = 2) while only one study reported a decrease in property crime. Of the studies that considered property crime in relation to COVID-19 restrictions, the majority reported a decrease in property crime (n = 9), while only a few studies reported mixed results (n = 3). This decrease was followed by an increase after relaxing restrictions for most studies (n = 2), while only one study reported no association. Note that mixed results were related to the type of property crime: residential burglaries generally decreased while non-residential burglaries increased, thus amounting to a mixed result. The global study also found that COVID-19 restrictions were related to a decrease in property crime and that this was related to the stringency of the restrictions.

Drug Crime

Five individual studies on drug crime (e.g., drug trafficking, possession of drugs) reported on five results from four countries based on crime records. All studies reported on data from western countries and corrected for seasonal components. One study found a decrease in drug crimes during COVID-19. Most studies found a decrease in drug crimes in relation to the introduction of COVID-19 restrictions (n = 3), while one study found mixed results and one study reported an increase in drug crime. After relaxation of restrictions, drug crime normalized. The study reporting an increase in drug crime included data from 15 districts in Queensland, Australia (Andresen & Hodgkinson, 2020) while the others studies report data from multiple cities from the US and UK. Queensland faced a long and strict lockdown during COVID-19 and many people lost their mining job in this area due to the drop in costs of coal and COVID-19 restrictions placed on mining workers. This might have led to enormous strain in this area and self-medicating behaviours such as drug use. Divergent findings might also be explained by the type of drug crime, since some studies found a decrease in drugs trafficking but not in the possession of drugs. Moreover, some studies found an immediate increase in drugs offenses directly after COVID-19 restrictions were imposed followed by a drop in drug crimes.

Fraud

Five individual studies on fraud (e.g., online fraud, scams, fraud by phone) reported on five results from five countries based on crime records and call data. Three studies reported on data from western countries, one on data from Mexico and one on data from China. All studies corrected for seasonal components. Most studies showed a decrease in fraud in response to COVID-19 restrictions (n = 3), while one study reported an increase, and one study reported no association. The study reporting an increase included data from the UK (Kemp et al., 2021), while the others studies reported data from China, Mexico and Australia. Kemp et al. (2021) specifically found the increase in fraud for individuals and less so for fraud reported by organizations. Other studies did not report about this distinction. Studies on the relationship between fraud and relaxations in restrictions mostly found no association (n = 2) while one study reported an increase.

Physical Violence

Eleven individual studies on physical violence (e.g., assault, battery, gun assault, physical abuse) reported on 13 results from seven countries based on crime records and call data. We also included a systematic review summarizing hospital data and one large study reporting on results from around the world (23 cities). The majority of the studies reported on data from western countries (10 results) and corrected for seasonal components (10 results). Individual studies on the change in physical violence during COVID-19 were inconclusive and showed mixed results (n = 2) or an increase in physical violence (n = 1). Note that all these studies only included data from the US. Most studies found a decrease in physical violence due to implementation of COVID-19 restrictions (n = 9) followed by an increase in physical violence after relaxing restrictions (n = 3). Only a few studies found no association between physical violence and the implementation of COVID-19 restrictions (n = 3 of which 2 based on data from the US). The global study reported a decrease in physical violence, but this effect was unrelated to the stringency of the restrictions. In contrast, hospital data did not show an effect of COVID-19 on physical violence. Most studies based on hospital data reported no change (n = 14), and some studies reported an increase (n = 8) or decrease (n = 6) in physical violence. Note that all studies which observed an increase in physical violence based on hospital data reported on data from the US.

Sexual Violence

Eight studies on sexual violence (e.g., rape, sexual assault) reported on 11 results from eight countries based on crime records and hospital data. Most studies reported on data from western countries (7 results) and corrected for seasonal components (6 results). Studies conclusively showed a decrease in sexual violence during COVID-19 in general (n = 4) and a decrease in sexual violence during COVID-19 restrictions (n = 8), while only one study reported mixed results.

Homicides

Nine individual studies on homicides (e.g., murder, manslaughter) reported on 11 results from eight countries based on crime records and autopsy reports. Most studies reported on data from western countries (7 results) and corrected for seasonal components (6 results). We also included a large study reporting on results across the globe (21 cities). Most studies reported no relationship between COVID-19 and homicides (n = 3) while only one study reported a decrease. Similarly, most studies found no significant relationship between the implementation of COVID-19 restrictions and homicides (n = 7) while only one study reported a decrease. No studies found an association between the relaxation of COVID-19 restrictions and homicides. The global study also found no significant relationship between COVID-19 restrictions and homicides.

Cybercrime

Three individual studies on cybercrime reported on three results from three countries western countries based on crime records. Two of these studies corrected for seasonal components. Study results on the relationship between COVID-19 (restrictions) and cybercrime were inconsistent: two studies found no association while one study reported an increase. One study assessed the relationship between cybercrime and relaxations in COVID-19 restrictions and found no association.

Domestic Violence

We were able to review two out of the three systematic reviews on domestic violence (the third did not allow for a review as it was unclear what data was the basis for the conclusions; Green et al., 2021). Piquero et al. (2021) reported an overall increase in domestic violence during COVID-19 with a medium effect size (d = 0.66) based on 18 studies. The majority of the included studies were based on data from the US, some included data from the same city, and most studies were not published at time of review. Interestingly, all types of data sources were combined in one analysis (e.g., call data, crime records and hospital data). Three out of the four studies who reported the largest increase in domestic violence reported on call data about domestic violence. In the second systematic review, Kourti et al. (2021) reported that calls related to domestic violence had increased during COVID-19 (three studies reported an increase and one a decrease) while data based on crime records was inconclusive (three studies reported an increase, two studies reported a decrease and three studies reported no significant change). Included studies were based on data from countries across the globe (although western countries were overrepresented).

Intimate Partner Violence

Fourteen studies on intimate partner violence (e.g., physical violence against an intimate partner or sexual violence against an intimate partner), reported on 14 results from 11 countries based on crime records, call data, hospital data, or cross-sectional studies. Most studies reported on data from western countries (8 results). Only three studies corrected for seasonal components. In looking at the five studies pertaining to rates of intimate partner violence during COVID-19 in general, most studies reported a decrease (n = 3 of which one based on a cross-sectional sample, one based on crime records, and one based on hospital data) while only 1 study reported mixed results (based on phone data) and one study reported no change (based on cross-sectional data). However, studies reporting on the change in intimate partner violence due to the implementation of COVID-19 restrictions were mixed: several studies reported an increase (n = 5 of which four based on a (usually small) cross-sectional sample and one based on call data), decrease (n = 3 of which two based on a small cross-sectional sample and one based on crime records) or no change (n = 2 of which one based on a cross-sectional sample and one based on crime records).

Other Crimes

We included one individual study on COVID-19-related crimes, which found that during COVID-19 the majority of the healthcare workers (> 70%) reported an increase in violence during work. Moreover, we included one individual study on crime related to nature which found no change in wildlife crime after COVID-19 restrictions were imposed. We also included one individual study on elderly abuse which found an increase in elderly abuse during COVID-19. Finally, we included one study on traffic crimes which reported a decrease in traffic crimes after COVID-19 restrictions were imposed. Note that most of these studies (except for traffic crimes) did not correct for seasonal components.

Discussion

The current review aimed to systematically examine studies on the impact of COVID-19 and COVID-19 lockdown measures on crime rates. We identified 46 studies with crime data from cities across the globe. COVID-19 affected almost all types of crimes except for homicides. Most crimes clearly decreased due to COVID-19 (measures) including sexual violence, robberies, property crime, fraud, drug crime, physical violence, and traffic crimes. Usually, a decreased crime rate due to COVID-19 restrictions was followed by an increase when restrictions were released. For cybercrimes and intimate partner violence, results were mixed. For domestic violence, results indicate that there has been an increase during COVID-19 but this seems to be mostly based on call data while evidence from crime records is mixed. We conclude that COVID-19 temporarily decreased crimes in the public domain with homicides as important exception.

We found consistent evidence for the decrease in crimes in the public domain in response to COVID-19 (restrictions). Most studies corrected for seasonal and annual changes in crime rates and the study quality was generally good. Note that for property crimes, residential property crimes decreased while non-residential property crimes often increased. Since COVID-19 measures often included staying at home, non-residential properties were easier targets for criminals. For drug crimes, some studies reported an immediate increase followed by a decrease due to COVID-19 restrictions. Most findings were based on data from western countries, Mexico, and Brazil. Most findings were not clearly different across regions except for physical violence. For physical violence, studies reporting on data from the US often reported an increase in violence or no change while studies reporting on data from other countries consistently reported a decrease in physical violence. This might be related to the racial conflicts and civil unrest related to the presidential elections in the US at that time. Generally, crime rates returned to pre-pandemic states when restrictions were alleviated. Thus, our findings indicate that these crime rates are affected by reduced opportunities due to restrictions that reduce mobility. These findings align with rational choice theory, deterrence theory, and to some extend to routine activities theory (Becker, 1968; Cohen & Felson, 1979; Karstedt, 1994). The reduction in crime rates seems to be specific (e.g., non-residential burglary is not affected by reduced mobility and thus not reduced), fast (immediate effects after lockdown measures were found) and universal (studies across the globe reported similar trends). Furthermore, stringency of lockdown measures and alleviation of restrictions were related to the crime rates pointing towards an effect of reduced opportunity rather than long-lasting changes.

We found an increase in domestic violence during COVID-19, potentially driven by call data rather than crime rates. On the one hand, crime rates might underestimate the incidence of domestic violence during COVID-19 because the COVID-19 lockdown measures might have complicated contact between victims and the police. On the other hand, studies reporting on call data often cannot discriminate domestic violence well from other issues (e.g., mental health issues), and given the impact of COVID-19 on (mental) health, this might also explain the increase in call data (Kourti et al., 2021). Alternatively, COVID-19 might also have worsened the situation in homes where domestic violence was already present thereby increasing the intensity and/or severity of the violence, leading to more calls but not more reported crimes. Future studies are needed to follow-up on the discrepancy between call data and crime rates. Note that previous meta-analyses generally had low quality, included many unpublished studies, and often it was not clear whether these studies corrected for seasonal effects. Since domestic violence usually increases in spring, ignoring seasonal trends might overestimate the effect of COVID-19 on the domestic violence (Leslie & Wilson, 2020).

We found mixed evidence for changes in intimate partner violence due to COVID-19 (measures). Although many studies have been published about intimate partner violence, the study quality was relatively low, and many studies only included cross-sectional data without corrections for seasonal or annual effects. This finding is in contrast with the general strain theory which posits that COVID-19 would increase strain and thereby also intimate partner violence.

We consistently found no change in homicides due to COVID-19 (measures). Homicides are often committed in the context of organized crime or gang-violence (National Gang Center; Vichi et al., 2020) and it has been suggested that members of such criminal organizations might not adhere to COVID-19 measures. Institutional reports and international media reports indicate that criminal organizations tried to retain or increase their criminal activities during COVID-19 (Aziani et al., 2021). In line with deterrence theory (Becker, 1968) the economic benefit of organized crimes might outweigh the risk of a COVID-19 infection or a fine for violating COVID-19 measures. Note that more than a quarter (~ 29%) of all homicides are committed by intimate partners or other family members (Cooper & Smith, 2011), so although call data indicated that domestic violence increased, this did not result in more homicides.

We did not observe changes in cybercrimes due to COVID-19 (measures), while routine activities theory suggests that crime would shift from an offline to an online setting. COVID-19 restrictions forced people to stay at home, possibly increasing online activity and increasing opportunities for cybercrimes. A recent study, however, found that online activities related to a high chance of victimization such as online shopping or dark web use were not significantly increased during COVID-19 (Hawdon et al., 2020). Thus, opportunity for cybercrimes might not have been increased. In line, people reported increased use of protection software against cybercrimes during COVID-19 such as virus software which is known to reduce the chance of cybercrimes (Hawdon et al., 2020).

We did not identify significant changes in nature crimes, we found that both elderly abuse and violence against healthcare workers was increased during COVID-19. We only identified a few studies on these crime rates so more research is needed to draw conclusions.

Together, our results clearly show the importance of opportunity for crimes and show that several theories on criminal behaviour are useful for explaining changes in crime rates during COVID-19 such as routine activities, rational choice, and deterrence theory. This has important implications for strategies to reduce criminal behaviour. For example, opportunity to commit crimes might be reduced through nudging (manipulating contextual cues; Sharma & Kilgatton, 2015). In a recent pilot study potential victims of theft from insecure vehicles were nudged to leave their vehicle more secure (Roach et al., 2017). Moreover, increasing the (perceived) probability of being apprehended and punished for crimes might also be effective in reducing criminal behaviour. For example, random breathing tests have been shown to be highly effective in reducing alcohol-related driver fatalities (Davey & Freeman, 2011). Note that such interventions should have a long duration to avoid a short-term effect followed by a return to normal levels. However, some predictions that can be made based on general crime theories are not supported by the data. Although we found a shift within a similar type of crime (i.e., from residential to non-residential property crimes), we found no shift from offline to online crimes. Previous studies indicated that criminal careers are usually clearly non-specialized (Gottfredson & Hirschi, 2016; Piquero et al., 2012) so it is remarkable that reductions in crime rates in an area with reduced opportunity were not clearly followed by increased crime rates in other areas. This might be (partly) explained by measures governments took to mitigate the impact of COVID-19. For example, in many countries governments launched campaigns to prevent domestic violence including social media campaigns, online support, more funding for alternative accommodations and the use of code words (Brink et al., 2021).

The current study is the first systematic review of changes in a broad range of crime rates during COVID-19. We used a systematic search strategy with two independent raters and we coded the quality of the included studies. This study also has some limitations. Firstly, most included studies reported data from western countries and especially the US has been overrepresented in research on crime rates. This might also relate to the availability of data on crime rates which is generally less in developing countries. Secondly, we were unable to check for publication bias since we did not include pooled effect sizes. Given the large number of studies in response to COVID-19, null findings may not have been published and therefore effects may have been overestimated. Thirdly, we only included published studies until the 6th of December 2021 and therefore we may have missed relevant unpublished literature by this date. Fourthly, most included studies used data from crime records with limited information about potential individual predictors of crimes such as COVID-19 related stressors/strains which might explain increased crime rates on an individual level. We recommend future studies to further examine individual predictors of crime during COVID-19.

Conclusion

COVID-19 has been referred to as the largest criminological experiment in history (Stickle & Felson, 2020). In line with general expectations from routine activities and rational choice theory, most crime rates decreased due to reduced opportunities, but quickly returned to pre-pandemic rates after COVID-19 measures were alleviated. Homicide was an exception, possibly related to the organized nature of the offence. Note that we do not know which COVID-19 measures were most important in reducing crime and how this effect was established since many of the COVID-19 measures might have led to reduced crime in various ways (e.g., closure of shops, home confinement, restrictions on (public) transport etc. might al have contributed to reduced crime via reduced mobility but also via other pathways such as reduced alcohol consumption in public areas). In contrast to expectations from routine activities theory, deterrence theory, and general strain theory, we did not find evidence for a shift from offline to online crime. Similarly, we did not find clear indications that reduction in crime rates in public places led to consistent increases in crime rates in a private context (intimate partner violence and domestic violence). For both intimate partner violence and domestic violence, more research is needed to (a) determine whether these crime rates were increased due to COVID-19 while correcting for seasonal and annual effects for call data and crime record data separately and (b) further investigate any increase in crime rates with respect to persistency after COVID-19 measures were alleviated. Our findings imply that reducing the opportunity to commit crimes is an effective strategy. In any future situation where restrictions are imposed which reduce mobility, policy makers can overall expect reduced crime rates. However, tailored preventative actions should be considered for crime rates which are potentially increased such as domestic violence (e.g., code words, media campaigns) and non-residential property crimes (e.g., better security measures). To conclude, we found that COVID-19 restrictions had a major impact on most crime rates across the globe. The findings may inform policy and future research on crime rates and assist in the anticipation of the impact of changes in COVID-19 restrictions on crime rates.

References

Abrams, D. S. (2021). COVID and crime: An early empirical look. Journal of Public Economics, 194, 104344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104344

Abujilban, S., Mrayan, L., Hamaideh, S., Obeisat, S., & Damra, J. (2022). Intimate partner violence against pregnant jordanian women at the time of COVID-19 pandemic’s quarantine. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(5–6), Np2442–Np2464. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260520984259

Agnew, R. (1992). Foundation for a general strain theory of crime and delinquency. Criminology, 30(1), 47–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.1992.tb01093.x

Aguero, J. M. (2021). COVID-19 and the rise of intimate partner violence. World Development, 137, 105217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105217

Andresen, M. A., & Hodgkinson, T. (2020). Somehow I always end up alone: COVID-19, social isolation and crime in Queensland Australia. Crime Science, 9(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40163-020-00135-4

Arenas-Arroyo, E., Fernandez-Kranz, D., & Nollenberger, N. (2021). Intimate partner violence under forced cohabitation and economic stress: Evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Public Economics, 194, 104350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104350

Ashby, M. P. J. (2020). Initial evidence on the relationship between the coronavirus pandemic and crime in the United States. Crime Science, 9(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40163-020-00117-6

Aziani, A., Bertoni, G. A., Jofre, M., & Riccardi, M. (2021). COVID-19 and organized crime: Strategies employed by criminal groups to increase their profits and power in the first months of the pandemic. Trends in Organized Crime. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12117-021-09434-x

Becker, G. S. (1968). Crime and punishment: An economic approach. In The economic dimensions of crime (pp. 13-68). Springer

Beiter, K., Hayden, E., Phillippi, S., Conrad, E., & Hunt, J. (2021). Violent trauma as an indirect impact of the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review of hospital reported trauma. American Journal of Surgery, 222(5), 922–932. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2021.05.004

Borkowski, P., Jazdzewska-Gutta, M., & Szmelter-Jarosz, A. (2021). Lockdowned: Everyday mobility changes in response to COVID-19. Journal of Transport Geography, 90, 102906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2020.102906

Bradbury-Jones, C., & Isham, L. (2020). The pandemic paradox: The consequences of COVID-19 on domestic violence. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29(13–14), 2047–2049. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15296

Brink, J., Cullen, P., Beek, K., & Peters, S. A. E. (2021). Intimate partner violence during the COVID-19 pandemic in Western and Southern European countries. European Journal of Public Health, 31(5), 1067-+. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckab093

Buil-Gil, D., Zeng, Y. Y., & Kemp, S. (2021). Offline crime bounces back to pre-COVID levels, cyber stays high: interrupted time-series analysis in Northern Ireland. Crime Science, 10(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40163-021-00162-9

Byard, R. W. (2021). Geographic variability in homicide rates following the COVID-19 pandemic. Forensic Science Medicine and Pathology, 17(3), 419–421. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12024-021-00370-4

Calderon-Anyosa, R. J. C., & Kaufman, J. S. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 lockdown policy on homicide, suicide, and motor vehicle deaths in Peru. Preventive Medicine, 143, 106331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106331

Caminha, C., Furtado, V., Pequeno, T. H. C., Ponte, C., Melo, H. P. M., Oliveira, E. A., & Andrade, J. S. (2017). Human mobility in large cities as a proxy for crime. PLoS One, 12(2), e0171609. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0171609

Campedelli, G. M., Aziani, A., & Favarin, S. (2021). Exploring the immediate effects of COVID-19 containment policies on crime: An empirical analysis of the short-term aftermath in Los Angeles. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 46(5), 704–727. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-020-09578-6

Capinha, M., Guinote, H., & Rijo, D. (2022). Intimate partner violence reports during the COVID-19 pandemic first year in Portuguese urban areas: A brief report. Journal of Family Violence, 37(6), 871–880. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-021-00332-y

Ceccato, V., Kahn, T., Herrmann, C., & Ostlund, A. (2022). Pandemic restrictions and spatiotemporal crime patterns in New York, Sao Paulo, and Stockholm. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 38(1), 120–149. https://doi.org/10.1177/10439862211038471

Chang, E. S., & Levy, B. R. (2021). High prevalence of elder abuse during the COVID-19 pandemic: Risk and resilience factors. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 29(11), 1152–1159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2021.01.007

Chen, P., Kurland, J., Piquero, A., & Borrion, H. (2021). Measuring the impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on crime in a medium-sized city in China. Journal of Experimental Criminology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-021-09486-7

Cheung, L., & Gunby, P. (2022). Crime and mobility during the COVID-19 lockdown: A preliminary empirical exploration. New Zealand Economic Papers, 56(1), 106–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/00779954.2020.1870535

Cohen, L. E., & Felson, M. (1979). Social-change and crime rate trends - routine activity approach. American Sociological Review, 44(4), 588–608. https://doi.org/10.2307/2094589

Cooper, A., & Smith, E. L. (2011). Homicide trends in the United States, 1980–2008. https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/htus8008.pdf. Accessed 02–01–2023

Davey, J. D., & Freeman, J. E. (2011). Improving road safety through deterrence-based initiatives: A review of research. Sultan Qaboos University Medical Journal, 11(1), 29–37.

de la Miyar, J. R. B., Hoehn-Velasco, L., & Silverio-Murillo, A. (2021). The U-shaped crime recovery during COVID-19: evidence from national crime rates in Mexico. Crime Science, 10(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40163-021-00147-8

Dogan, G., Carroll, R., & Demirci, G. M. (2021). 911 4 COVID-19: Analyzing Impact of COVID-19 on 911 Call Behavior. 2021 10th International Conference on Software and Computer Applications.

Doğan, M. (2021). Physical, psychosocial, occupational problems and protection behaviors experienced by pre-hospital emergency healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Contemporary Medicine, 11(2), 174–179.

Ebert, C., & Steinert, J. I. (2021). Prevalence and risk factors of violence against women and children during COVID-19, Germany. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 99(6), 429–438. https://doi.org/10.2471/Blt.20.270983

El-Nimr, N. A., Mamdouh, H. M., Ramadan, A., El Saeh, H. M., & Shata, Z. N. (2021). Intimate partner violence among Arab women before and during the COVID-19 lockdown. Journal of the Egyptian Public Health Association, 96(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42506-021-00077-y

Ertan, D., El-Hage, W., Thierree, S., Javelot, H., & Hingray, C. (2020). COVID-19: urgency for distancing from domestic violence. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1800245. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2020.1800245

Estevez-Soto, P. R. (2021). Crime and COVID-19: effect of changes in routine activities in Mexico City. Crime Science, 10(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40163-021-00151-y

Gosangi, B., Park, H., Thomas, R., Gujrathi, R., Bay, C. P., Raja, A. S., Seltzer, S. E., Balcom, M. C., McDonald, M. L., Orgill, D. P., Harris, M. B., Boland, G. W., Rexrode, K., & Khurana, B. (2021). Exacerbation of physical intimate partner violence during COVID-19 pandemic. Radiology, 298(1), E38–E45. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2020202866

Gottfredson, M. R., & Hirschi, T. (2016). The criminal career perspective as an explanation of crime and a guide to crime control policy: The view from general theories of crime. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 53(3), 406–419. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022427815624041

Green, H., Fernandez, R., & MacPhail, C. (2021). The social determinants of health and health outcomes among adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Public Health Nursing, 38(6), 942–952. https://doi.org/10.1111/phn.12959

Hawdon, J., Parti, K., & Dearden, T. E. (2020). Cybercrime in America amid COVID-19: The initial results from a natural experiment. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 45(4), 546–562. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-020-09534-4

Helsingen, L. M., Refsum, E., Gjostein, D. K., Loberg, M., Bretthauer, M., Kalager, M., Emilsson, L., & Grp, C. E. R. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic in Norway and Sweden - threats, trust, and impact on daily life: a comparative survey. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1597. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09615-3

Hoehn-Velasco, L., Silverio-Murillo, A., & de la Miyar, J. R. B. (2021). The great crime recovery: Crimes against women during, and after, the COVID-19 lockdown in Mexico*. Economics & Human Biology, 41, 100991. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2021.100991

Karstedt, S., Clarke, R. V., & Felson, M. (1994). Advances in criminological theory, vol 5, routine activity and rational choice. Contemporary Sociology-a Journal of Reviews, 23(6), 859–860. https://doi.org/10.2307/2076087

Kaukinen, C. (2020). When stay-at-home orders leave victims unsafe at home: Exploring the risk and consequences of intimate partner violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 45(4), 668–679. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-020-09533-5

Kemp, S., Buil-Gil, D., Moneva, A., Miro-Llinares, F., & Diaz-Castano, N. (2021). Empty streets, busy internet: A time-series analysis of cybercrime and fraud trends during COVID-19. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 37(4), 480–501. https://doi.org/10.1177/10439862211027986

Koju, N. P., Kandel, R. C., Acharya, H. B., Dhakal, B. K., & Bhuju, D. R. (2021). COVID-19 lockdown frees wildlife to roam but increases poaching threats in Nepal. Ecology and Evolution, 11(14), 9198–9205. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.7778

Kourti, A., Stavridou, A., Panagouli, E., Psaltopoulou, T., Spiliopoulou, C., Tsolia, M., Sergentanis, T. N., & Tsitsika, A. (2021). Domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Trauma Violence & Abuse. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380211038690

Kourti, A., Stavridou, A., Panagouli, E., Psaltopoulou, T., Spiliopoulou, C., Tsolia, M., Sergentanis, T. N., & Tsitsika, A. (2023). Domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Trauma Violence & Abuse, 24(2), 719–745. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380211038690. 15248380211038690.

Langton, S., Dixon, A., & Farrell, G. (2021). Six months in: pandemic crime trends in England and Wales. Crime Science, 10(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40163-021-00142-z

Leslie, E., & Wilson, R. (2020). Sheltering in place and domestic violence: Evidence from calls for service during COVID-19. Journal of Public Economics, 189, 104241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104241

Lin, M. J. (2008). Does unemployment increase crime? Evidence from US data 1974–2000. Journal of Human Resources, 43(2), 413–436. https://doi.org/10.1353/jhr.2008.0022

Lopez, E., & Rosenfeld, R. (2021). Crime, quarantine, and the US coronavirus pandemic. Criminology & Public Policy, 20(3), 401–422. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12557

Mahmood, K. I., Shabu, S. A., Mamen, K. M., Hussain, S. S., Kako, D. A., Hinchliff, S., & Shabila, N. P. (2022). The impact of COVID-19 related lockdown on the prevalence of spousal violence against women in Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(13–14), Np11811–Np11835. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260521997929

Marroquin, B., Vine, V., & Morgan, R. (2020). Mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: Effects of stay-at-home policies, social distancing behavior, and social resources. Psychiatry Research, 293, 113419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113419

McNeil, A., Hicks, L., Yalcinoz-Ucan, B., & Browne, D. T. (2023). Prevalence & correlates of intimate partner violence During COVID-19: A rapid review. Journal of Family Violence, 38(2), 241–261. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-022-00386-6

Monteiro, J. D. M., de Carvalho, E. F., & Gomes, R. C. (2021). Crime and police activity during the COVID-19 pandemic in Rio de Janeiro. Brazil. Ciencia & Saude Coletiva, 26(10), 4703–4714. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-812320212610.09352021

Morgan, A., & Boxall, H. (2020). Social isolation, time spent at home, financial stress and domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice(609). <Go to ISI>://WOS:000582108900001.

Moslehi, S., Parasnis, J., Tani, M., & Vejayaratnam, J. (2021). Assaults during lockdown in New South Wales and Victoria. Australian Journal of Labour Economics, 24(2), 199–212.

Muldoon, K. A., Denize, K. M., Talarico, R., Fell, D. B., Sobiesiak, A., Heimerl, M., & Sampsel, K. (2021). COVID-19 pandemic and violence: rising risks and decreasing urgent care-seeking for sexual assault and domestic violence survivors. BMC Medicine, 19(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-020-01897-z

National Gang Center. National Youth Gang Survey Analysis. https://nationalgangcenter.ojp.gov/survey-analysis. Accessed 02–01–2023

NIH. (2013). Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-sectional Studies. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools. Accessed 02–01–2023

Nivette, A. E., Zahnow, R., Aguilar, R., Ahven, A., Amram, S., Ariel, B., Burbano, M. J. A., Astolfi, R., Baier, D., Bark, H. M., Beijers, J. E. H., Bergman, M., Breetzke, G., Concha-Eastman, I. A., Curtis-Ham, S., Davenport, R., Diaz, C., Fleitas, D., Gerell, M., . . . Eisner, M. P. (2021). A global analysis of the impact of COVID-19 stay-at-home restrictions on crime. Nature Human Behaviour, 5(7), 868–877. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01139-z

O'Donnell, M. L., & Greene, T. (2021). Understanding the mental health impacts of COVID-19 through a trauma lens. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1982502. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2021.1982502

Ojeahere, M. I., Kumswa, S. K., Adiukwu, F., Plang, J. P., & Taiwo, Y. F. (2022). Intimate partner violence and its mental health implications amid COVID-19 lockdown: Findings among Nigerian couples. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(17–18), Np15434–Np15454. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605211015213

Olff, M., Primasari, I., Qing, Y. L., Coimbra, B. M., Hovnanyan, A., Grace, E., Williamson, R. E., Hoeboer, C. M., & Consortium, G.-C. (2021). Mental health responses to COVID-19 around the world. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1929754. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2021.1929754

Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., & Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 5. ARTN 210. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

Pattojoshi, A., Sidana, A., Garg, S., Mishra, S. N., Singh, L. K., Goyal, N., & Tikka, S. K. (2021). Staying home is NOT ‘staying safe’: A rapid 8-day online survey on spousal violence against women during the COVID-19 lockdown in India. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 75(2), 64–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/pcn.13176

Payne, J. L., Morgan, A., & Piquero, A. R. (2022). COVID-19 and social distancing measures in Queensland, Australia, are associated with short-term decreases in recorded violent crime. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 18(1), 89–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-020-09441-y

Pikoulis, E., Solomos, Z., Riza, E., Puthoopparambir, S. J., Pikoulis, A., Karamagioli, E., & Puchner, K. P. (2020). Gathering evidence on the decreased emergency room visits during the coronavirus disease 19 pandemic. Public Health, 185, 42–43. https://doi.org/10.1010/j.puhe.2020.05.036

Piquero, A. R., Jennings, W. G., & Barnes, J. C. (2012). Violence in criminal careers: A review of the literature from a developmental life-course perspective. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 17(3), 171–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2012.02.008

Piquero, A. R., Jennings, W. G., Jemison, E., Kaukinen, C., & Knaul, F. M. (2021). Domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic-Evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Criminal Justice, 74, 101806. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2021.101806

Plasilova, L., Hula, M., Krejcova, L., & Klapilova, K. (2021). The COVID-19 pandemic and intimate partner violence against women in the Czech Republic: Incidence and associated factors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(19), 10502. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910502

Regalado, J., Timmer, A., & Jawaid, A. (2022). Crime and deviance during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sociology Compass, 16(4). ARTN e12974. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12974

Roach, J., Weir, K., Phillips, P., Gaskell, K., & Walton, M. (2017). Nudging down theft from insecure vehicles. A pilot study. International Journal of Police Science & Management, 19(1), 31–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461355716677876

Sakelliadis, E. I., Katsos, K. D., Zouzia, E. I., Spiliopoulou, C. A., & Tsiodras, S. (2020). Impact of Covid-19 lockdown on characteristics of autopsy cases in Greece. Comparison between 2019 and 2020. Forensic Science International, 313, 110365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2020.110365

Sarel, R. (2022). Crime and punishment in times of pandemics. European Journal of Law and Economics, 54(2), 155–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-021-09720-7

Sharma, D., & Kilgatton, S. (2015). Nudge; Don’t judge: Using nudge theory to deter shoplifters. 11th European Academy of Design Conference.

Shen, Y. C., Fu, R., & Noguchi, H. (2021). COVID-19’s lockdown and crime victimization: The state of emergency under the Abe administration. Asian Economic Policy Review, 16(2), 327–348. https://doi.org/10.1111/aepr.12339

Speziale, N. (2014). Does unemployment increase crime? Evidence from Italian provinces. Applied Economics Letters, 21(15), 1083–1089. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2014.909568

Stickle, B., & Felson, M. (2020). Crime rates in a pandemic: The largest criminological experiment in history. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 45(4), 525–536. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-020-09546-0

Talic, S., Shah, S., Wild, H., Gasevic, D., Maharaj, A., Ademi, Z., Li, X., Xu, W., Mesa-Eguiagaray, I., Rostron, J., Theodoratou, E., Zhang, X. M., Motee, A., Liew, D., & Ilic, D. (2021). Effectiveness of public health measures in reducing the incidence of covid-19, SARS-CoV-2 transmission, and covid-19 mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ-British Medical Journal, 375,e068302. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2021-068302

Tull, M. T., Edmonds, K. A., Scamaldo, K. M., Richmond, J. R., Rose, J. P., & Gratz, K. L. (2020). Psychological outcomes associated with stay-at-home orders and the perceived impact of COVID-19 on daily life. Psychiatry Research, 289, 113098. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113098

Vichi, M., Ghirini, S., Roma, P., Mandarelli, G., Pompili, M., & Ferracuti, S. (2020). Trends and patterns in homicides in Italy: A 34-year descriptive study. Forensic Science International, 307, 110141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2020.110141

Vives-Cases, C., La Parra-Casado, D., Estevez, J. F., Torrubiano-Dominguez, J., & Sanz-Barbero, B. (2021). Intimate partner violence against women during the COVID-19 lockdown in Spain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(9). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094698

Walsh, A. R., Sullivan, S., & Stephenson, R. (2022). Intimate partner violence experiences during COVID-19 among male couples. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(15–16), Np14166–Np14188. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605211005135

Wang, J. J. J., Fung, T., & Weatherburn, D. (2021). The impact of the COVID-19, social distancing, and movement restrictions on crime in NSW, Australia. Crime Science, 10(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40163-021-00160-x

White, M. D., & Fradella, H. F. (2020). Policing a pandemic: Stay-at-home orders and what they mean for the police. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 45(4), 702–717. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-020-09538-0

Zhang, S. X., Miller, S. O., Xu, W., Yin, A., Chen, B. Z., Delios, A., Dong, R. K., Chen, R. Z., McIntyre, R. S., Wan, X., Wang, S. H., & Chen, J. Y. (2022). Meta-analytic evidence of depression and anxiety in Eastern Europe during the COVID-19 pandemic. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 13(1), 2000132. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2021.2000132

Funding

This study is funded by NWO (NWA.1418.20.011). The funder had no role in the design of this study, data collection, analyses, interpretation of the data, or decision to submit results.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hoeboer, C.M., Kitselaar, W.M., Henrich, J.F. et al. The Impact of COVID-19 on Crime: a Systematic Review. Am J Crim Just 49, 274–303 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-023-09746-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-023-09746-4