Abstract

The maldistribution of family physicians challenges equitable primary care access in Canada. The Theory of Social Attachment suggests that preferential selection and distributed training interventions have potential in influencing physician disposition. However, evaluations of these approaches have focused predominantly on rural underservedness, with little research considering physician disposition in other underserved communities. Accordingly, this study investigated the association between the locations from which medical graduates apply to medical school, their undergraduate preclerkship, clerkship, residency experiences, and practice as indexed across an array of markers of underservedness. We built association models concerning the practice location of 347 family physicians who graduated from McMaster University’s MD Program between 2010 and 2015. Postal code data of medical graduates’ residence during secondary school, pre-clerkship, clerkship, residency and eventual practice locations were coded according to five Statistics Canada indices related to primary care underservedness: relative rurality, employment rate, proportion of visible minorities, proportion of Indigenous peoples, and neighbourhood socioeconomic status. Univariate and multivariable logistic regression models were then developed for each dependent variable (i.e., practice location expressed in terms of each index). Residency training locations were significantly associated with practice locations across all indices. The place of secondary school education also yielded significant relationships to practice location when indexed by employment rate and relative rurality. Education interventions that leverage residency training locations may be particularly influential in promoting family physician practice location. The findings are interpreted with respect to how investment in education policies can promote physician practice in underserved communities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Available

These data are not available for use by other researchers.

References

Asada, Y., & Kephart, G. (2007). Equity in health services use and intensity of use in Canada. BMC Health Services Research, 7(1), 1–12.

Association of Faculties of Medicine Canada (2018). Applicants to MD programs in Canadian faculties of medicine. Association of Faculties of Medicine Canada. Retrieved from https://afmc.ca/sites/default/files/pdf/CMES/CMES2018-Complete_EN.pdf.

Associations between education policies and the geographic disposition of family physicians: A retrospective observational study of McMaster University education data.

Bade, E., Baumgardner, D., & Brill, J. (2009). The central city site: An urban underserved family medicine training track. Family Medicine, 41(1), 34–38.

Barer, M. L., Wood, L. C., & Schneider, D. G. (1999). Toward improved access to medical services for relatively underserved populations: Canadian approaches, foreign lessons.

Boelen, C. (2011). Global consensus on the social accountability of medical schools. Sante Publique, 23(3), 247–250.

Bowlby, J. (1979). The making and breaking of affectional bonds. Lecture 7. J. Bowlby: The Making and Breaking of Affectional Bonds, London (Tavistock Publications) 1979, pp. 126–143.

Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base. Routledge.

Canadian Institute for Health Information (2012). Disparities in primary health care experiences among Canadians with ambulatory care sensitive conditions. Canadian Institute for Health Information. Retrieved from https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/PHC_Experiences_AiB2012_E.pdf.

Canadian Institute of Health Information (2018). Canadian Institute of Health Information. Retrieved from https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/cphi-toolkit-area-level-measurement-pccf-2018-en-web.pdf.

Cantor, J. C., Miles, E. L., Baker, L. C., & Barker, D. C. (1996). Physician service to the underserved: Implications for affirmative action in medical education. Inquiry : A Journal Of Medical Care Organization, Provision And Financing, 167–180.

Chan, B. T., Degani, N., Crichton, T., Pong, R. W., Rourke, J. T., Goertzen, J., & McCready, B. (2005). Factors influencing family physicians to enter rural practice: Does rural or urban background make a difference? Canadian Family Physician, 51(9), 1246–1247.

Clarke, J. (2016). Difficulty accessing health care services in Canada. Statistics Canada. Retrieved from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/82-624-x/2016001/article/14683-eng.pdf?st=X0M0-F4i.

Continelli, T., McGinnis, S., & Holmes, T. (2010). The effect of local primary care physician supply on the utilization of preventive health services in the United States. Health & Place, 16(5), 942–951.

Crooks, V. A., & Schuurman, N. (2012). Interpreting the results of a modified gravity model: Examining access to primary health care physicians in five canadian provinces and territories. BMC Health Services Research, 12(1), 1–13.

Dunlop, S., Coyte, P. C., & McIsaac, W. (2000). Socio-economic status and the utilisation of physicians’ services: Results from the Canadian National Population Health Survey. Social Science & Medicine, 51(1), 123–133.

Dussault, G., & Franceschini, M. C. (2006). Not enough there, too many here: Understanding geographical imbalances in the distribution of the health workforce. Human Resources for Health, 4(1), 1–16.

Eley, D. S., Synnott, R., Baker, P. G., & Chater, A. B. (2012). A decade of Australian Rural Clinical School graduates–where are they and why? Rural and Remote Health, 12(1), 138–147.

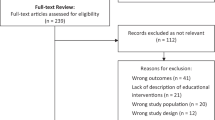

Elma, A., Nasser, M., Yang, L., Chang, I., Bakker, D., & Grierson, L. (2022). Medical education interventions influencing physician distribution into underserved communities: A scoping review. Human Resources for Health, 20(1), 1–14.

Ferguson, W. J., Cashman, S. B., Savageau, J. A., & Lasser, D. H. (2009). Family medicine residency characteristics associated with practice in a health professions shortage area. Family Medicine, 41(6), 405–410.

Gilliland, J. A., Shah, T. I., Clark, A., Sibbald, S., & Seabrook, J. A. (2019). A geospatial approach to understanding inequalities in accessibility to primary care among vulnerable populations. PloS One, 14(1), e0210113.

Goodfellow, A., Ulloa, J. G., Dowling, P. T., Talamantes, E., Chheda, S., Bone, C., & Moreno, G. (2016). Predictors of primary care physician practice location in underserved urban and rural areas in the United States: A systematic literature review. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 91(9), 1313.

Government of Canada (2012). Health Human Resource Strategy. Government of Canada. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/health-care-system/health-human-resources/strategy.html.

Gray, J. D., Steeves, L. C., & Blackburn, J. W. (1994). The Dalhousie University experience of training residents in many small communities. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 69(10), 847–851.

Grierson, L., & Vanstone, M. (2021). The allocation of Medical School Spaces in Canada by Province and Territory: The need for evidence-based Health Workforce Policy. Healthcare Policy, 16(3), 106.

Grobler, L., Marais, B. J., & Mabunda, S. (2015). Interventions for increasing the proportion of health professionals practising in rural and other underserved areas. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (6).

Hay, C., Pacey, M., Bains, N., & Ardal, S. (2010). Understanding the unattached population in Ontario: Evidence from the Primary Care Access Survey (PCAS). Healthcare Policy, 6(2), 33.

Health Canada (2008). Overview of the Cost of Training Health Professionals. Government of Canada. Retrieved from https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2009/sc-hc/H29-1-2009E.pdf.

Health Canada. Social Accountability: A vision for Canadian medical schools. (2001). Government of Canada. Retrieved from https://www.afmc.ca/future-of-medical-education-in-canada/medical-doctor-project/pdf/sa_vision_canadian_medical_schools_en.pdf.

Heng, D., Pong, R. W., Chan, B. T., & Degani, N. (2007). Graduates of northern Ontario family medicine residency programs practise where they train. Canadian Journal of Rural Medicine, 12(3), 146.

Henry, J. A., Edwards, B. J., & Crotty, B. (2009). Why do medical graduates choose rural careers? Rural and Remote Health, 9(1), 1–13.

Hogenbirk, J. C., Timony, P. E., French, M. G., Strasser, R., Pong, R. W., Cervin, C., & Graves, L. (2016). Milestones on the social accountability journey: Family medicine practice locations of Northern Ontario School of Medicine graduates. Canadian Family Physician, 62(3), e138–e145.

Huang, Y., Meyer, P., & Jin, L. (2018). Neighborhood socioeconomic characteristics, healthcare spatial access, and emergency department visits for ambulatory care sensitive conditions for elderly. Preventive Medicine Reports, 12, 101–105.

Hughes, S., Zweifler, J., Schafer, S., Smith, M. A., Athwal, S., & Blossom, H. J. (2005). High school census tract information predicts practice in rural and minority communities. The Journal of Rural Health, 21(3), 228–232.

Hussein, M., Roux, D., A. V., & Field, R. I. (2016). Neighborhood socioeconomic status and primary health care: Usual points of access and temporal trends in a major US urban area. Journal of Urban Health, 93(6), 1027–1045.

Kevin Wasko, M. A. (2014). Medical practice in rural Saskatchewan: Factors in physician recruitment and retention. Canadian Journal of Rural Medicine, 19(3), 93.

Khan, R., Apramian, T., Kang, J. H., Gustafson, J., & Sibbald, S. (2020). Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of canadian medical students: A cross-sectional study. BMC Medical Education, 20(1), 1–8.

Khandor, E., Mason, K., Chambers, C., Rossiter, K., Cowan, L., & Hwang, S. W. (2011). Access to primary health care among homeless adults in Toronto, Canada: Results from the Street Health survey. Open Medicine, 5(2), e94.

Landry, M., Schofield, A., Bordage, R., & Bélanger, M. (2011). Improving the recruitment and retention of doctors by training medical students locally. Medical Education, 45(11), 1121–1129.

Law, M., Wilson, K., Eyles, J., Elliott, S., Jerrett, M., Moffat, T., & Luginaah, I. (2005). Meeting health need, accessing health care: The role of neighbourhood. Health & Place, 11(4), 367–377.

Lee, J., Walus, A., Billing, R., & Hillier, L. M. (2016). The role of distributed education in recruitment and retention of family physicians. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 92(1090), 436–440.

Liaw, W., Bazemore, A., Xierali, I., Walden, J., Diller, P., & Morikawa, M. J. (2013). The Association between Global Health Training and Underserved Care. Family Medicine, 45(4), 263–267.

Lu, D. J., Hakes, J., Bai, M., Tolhurst, H., & Dickinson, J. A. (2008). Rural intentions: Factors affecting the career choices of family medicine graduates. Canadian Family Physician, 54(7), 1016–1017.

Mathews, M., & Edwards, A. C. (2004). Having a regular doctor: Rural, semiurban and urban differences in Newfoundland. Canadian Journal of Rural Medicine, 9(3), 166–172.

Mathews, M., Rourke, J. T., & Park, A. (2008). The contribution of Memorial University’s medical school to rural physician supply. Canadian Journal of Rural Medicine, 13(1), 15–21.

Mathews, M., Ryan, D., & Samarasena, A. (2015). Work locations in 2014 of medical graduates of Memorial University of Newfoundland: A cross-sectional study. Canadian Medical Association Open Access Journal, 3(2), E217–E222.

McDonald, J. T., & Conde, H. (2010). Does geography matter? The health service use and unmet health care needs of older Canadians. Canadian Journal on Aging/La Revue canadienne du vieillissement, 29(1), 23–37.

McGrail, M. R., Humphreys, J. S., & Joyce, C. M. (2011). Nature of association between rural background and practice location: A comparison of general practitioners and specialists. BMC Health Services Research, 11(1), 1–8.

McMaster University, Undergraduate MD Program. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://mdprogram.mcmaster.ca/md-program.

Morris, C. G., Johnson, B., Kim, S., & Chen, F. (2008). Training family physicians in community health centers: A health workforce solution. Family Medicine, 40(4), 271.

Myhre, D. L., & Hohman, S. (2012). Going the distance: Early results of a distributed medical education initiative for Royal College residencies in Canada. Rural and Remote Health, 12(4), 1–7.

OPHRDC. Ontario Physician Registry Methodology. The Ontario physician Human Resources Data Centre. Retrieved from https://www.ophrdc.org/physician-reports/the-ontario-physician-registry-background/.

Petrany, S. M., & Gress, T. (2013). Comparison of academic and practice outcomes of rural and traditional track graduates of a family medicine residency program. Academic Medicine, 88(6), 819–823.

Playford, D., Ngo, H., Gupta, S., & Puddey, I. B. (2017). Opting for rural practice: The influence of medical student origin, intention and immersion experience. Medical Journal of Australia, 207(4), 154–158.

Pong, R. W., & Pitblado, J. R. (2005). & Canadian Institute for Health Information. Geographic distribution of physicians in Canada: Beyond how many and where. Canadian Institute for Health Information. Retrieved from https://www.deslibris.ca/ID/219728.

Pong, R. W., Chan, B. T., Crichton, T., & Goertzen, J. (2007). Big cities and bright lights: Rural-and northern-trained physicians in urban practice. Canadian Journal of Rural Medicine, 12(3), 153.

Pong, R. W., DesMeules, M., Heng, D., Lagacé, C., Guernsey, J. R., Kazanjian, A., & Luo, W. (2011). Patterns of health services utilization in rural Canada. Chronic Diseases and Injuries in Canada, 31, 1–36.

Puddey, I. B., Playford, D. E., & Mercer, A. (2017). Impact of medical student origins on the likelihood of ultimately practicing in areas of low vs high socio-economic status. BMC Medical Education, 17(1), 1–13.

Quinn, K. J., Kane, K. Y., Stevermer, J. J., Webb, W. D., Porter, J. L., Williamson, H. A. Jr., & Hosokawa, M. C. (2011). Influencing residency choice and practice location through a longitudinal rural pipeline program. Academic Medicine, 86(11), 1397–1406.

Rabinowitz, H. K., Diamond, J. J., Veloski, J. J., & Gayle, J. A. (2000). The impact of multiple predictors on generalist physicians’ care of underserved populations. American Journal of Public Health, 90(8), 1225.

Rabinowitz, H. K., Diamond, J. J., Markham, F. W., & Rabinowitz, C. (2005). Long-term retention of graduates from a program to increase the supply of rural family physicians. Academic Medicine, 80(8), 728–732.

Rabinowitz, H. K., Diamond, J. J., Markham, F. W., & Santana, A. J. (2012). The relationship between entering medical students’ backgrounds and career plans and their rural practice outcomes three decades later. Academic Medicine, 87(4), 493–497.

Reed, A. J., Schmitz, D., Baker, E., Girvan, J., & McDonald, T. (2017). Assessment of factors for recruiting and retaining medical students to rural communities using the Community Apgar Questionnaire. Family Medicine, 49(2), 132–136.

Richards, H. M., Farmer, J., & Selvaraj, S. (2005). Sustaining the rural primary healthcare workforce: Survey of healthcare professionals in the scottish highlands. Rural and Remote Health, 5(1), 1–14.

Robinson, M., & Slaney, G. M. (2013). Choice or chance! The influence of decentralised training on GP retention in the Bogong region of Victoria and New South Wales. Rural and Remote Health, 13(1), 127–138.

Roy, V., Hurley, K., Plumb, E., Castellan, C., & McManus, P. (2015). Urban underserved program. Family Medicine, 47(5), 373–377.

Scott’s Directories. Canadian Medical Directory and Database. Scott’s Directories. Retrieved from https://www.scottsdirectories.com/canadian-directories/canadian-medical-directory/.

Shah, B. R., Gunraj, N., & Hux, J. E. (2003). Markers of access to and quality of primary care for aboriginal people in Ontario, Canada. American Journal of Public Health, 93(5), 798–802.

Shah, T. I., Bell, S., & Wilson, K. (2016). Spatial accessibility to health care services: Identifying under-serviced neighbourhoods in canadian urban areas. PloS One, 11(12), e0168208.

Shah, T. I., Milosavljevic, S., & Bath, B. (2017). Determining geographic accessibility of family physician and nurse practitioner services in relation to the distribution of seniors within two canadian Prairie provinces. Social Science & Medicine, 194, 96–104.

Shah, T. I., Clark, A. F., Seabrook, J. A., Sibbald, S., & Gilliland, J. A. (2020). Geographic accessibility to primary care providers: Comparing rural and urban areas in Southwestern Ontario. The Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe canadien, 64(1), 65–78.

Sibley, L. M., & Weiner, J. P. (2011). An evaluation of access to health care services along the rural-urban continuum in Canada. BMC Health Services Research, 11(1), 1–11.

Smucny, J., Beatty, P., Grant, W., Dennison, T., & Wolff, L. T. (2005). An evaluation of the rural medical education program of the State University of New York Upstate Medical University, 1990–2003. Academic Medicine, 80(8), 733–738.

StataCorp. (2013). Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station. StataCorp LP.

Statistics Canada (2012). Summary table of peer groups and principal characteristics. Statistics Canada. Retrieved from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-221-x/2012001/regions/hrt4-eng.htm.

Statistics Canada (2015). Access to a regular medical doctor. Government of Canada. Retrieved from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-625-x/2015001/article/14177-eng.htm.

Statistics Canada (2015). Variable definitions. Statistics Canada. Retrieved from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-402-x/2015001/regions/app-ann/ap-anA-eng.htm.

Statistics Canada (2018). Health Region Peer groups – Working Paper. Statistics Canada. Available from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-622-x/82-622-x2018001-eng.htm.

Statistics Canada (2019). Postal Code Conversion File Plus (PCCF+) Version 7 C.

Statistics Canada (2021). Indigenous identity of person. Statistics Canada. Retrieved from https://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p3Var.pl?Function=DEC&Id=42927.

Statistics Canada (2021). Visible minority of person. Statistics Canada. Retrieved from https://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p3Var.pl?Function=DEC&Id=45152.

Statistics Canada. (2017). Postal Code Conversion file plus (PCCF +) version 6D, reference guide. Statistics Canada.

Strasser, R. P., Lanphear, J. H., McCready, W. G., Topps, M. H., Hunt, D. D., & Matte, M. C. (2009). Canada’s new medical school: The Northern Ontario School of Medicine: Social accountability through distributed community engaged learning. Academic Medicine, 84(10), 1459–1464.

Strasser, R., Hogenbirk, J. C., Lewenberg, M., Story, M., & Kevat, A. (2010). Starting rural, staying rural: How can we strengthen the pathway from rural upbringing to rural practice? Australian Journal of Rural Health, 18(6), 242–248.

Streeter, R. A., Snyder, J. E., Kepley, H., Stahl, A. L., Li, T., & Washko, M. M. (2020). The geographic alignment of primary care Health Professional shortage areas with markers for social determinants of health. PloS One, 15(4), e0231443.

Talbot, Y., Fuller-Thomson, E., Tudiver, F., Habib, Y., & McIsaac, W. J. (2001). Canadians without regular medical doctors. Who are they? Canadian Family Physician, 47(1), 58–64.

Tiagi, R. (2016). Access to and utilization of health care services among Canada’s immigrants. International Journal of Migration Health and Social Care, 12(2), 146–156.

Turpel-Lafond, M. E., & Johnson, H. (2021). In plain sight: Addressing indigenous-specific racism and discrimination in BC health care. BC Studies: The British Columbian Quarterly, 209, 7–17.

Walker, J. H., Dewitt, D. E., Pallant, J. F., & Cunningham, C. E. (2012). Rural origin plus a rural clinical school placement is a significant predictor of medical students’ intentions to practice rurally: A multi-university study. Rural and Remote Health, 12(1), 109–117.

Wang, L., Guruge, S., & Montana, G. (2019). Older immigrants’ access to primary health care in Canada: A scoping review. Canadian Journal on Aging/La Revue canadienne du vieillissement, 38(2), 193–209.

Wayne, S. J., Kalishman, S., Jerabek, R. N., Timm, C., & Cosgrove, E. (2010). Early predictors of physicians’ practice in medically underserved communities: A 12-year follow-up study of University of New Mexico School of Medicine graduates. Academic Medicine, 85(10), S13–S16.

Wenghofer, E. F., Hogenbirk, J. C., & Timony, P. E. (2017). Impact of the rural pipeline in medical education: Practice locations of recently graduated family physicians in Ontario. Human Resources for Health, 15(1), 1–6.

Woloschuk, W., & Tarrant, M. (2002). Does a rural educational experience influence students’ likelihood of rural practice? Impact of student background and gender. Medical Education, 36(3), 241–247.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Lynda Chryslar from the Ontario Physician Human Resources Data Centre and Geoff Barnum from the Canadian Post-MD Education Registry.

Funding

This work was funded by McMaster University’s 2020 Faculty of Health Sciences’ Education Scholarship Fund and the 2020 Hamilton Academic Family Medicine Associates Research Grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LG designed and supervised all aspects of this study. MMe conducted the data analysis. AE and MMa led the research data management and supported statistical analyses. LG led the writing of the manuscript. All authors (LG, MMe, AE, MMa, DB, NJ, MA, GA) participated in data analysis and interpretation and contributed to the critical revision of the paper, approved the final manuscript for publication, and have agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Grierson, L., Mercuri, M., Elma, A. et al. Associations between education policies and the geographic disposition of family physicians: a retrospective observational study of McMaster University education data. Adv in Health Sci Educ (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-023-10273-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-023-10273-4