Abstract

The type of mood or tense marking that causes counterfactuality inferences—as figuring prominently, but far from exclusively, in counterfactual conditionals—has not yet received a comprehensive and compositional analysis. Focusing on four languages, the paper presents under-appreciated facts and a novel theory where the mood serves to activate alternatives to modal operators, particularly one: the identity operator, often giving rise to counterfactual implicatures.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The aim of this paper is to show that what I will call counterfactual mood in two Germanic and two Slavic languages—German, Norwegian, Czech, Russian—calls for a treatment where the mood operates on a generalized modal and contrasts it with the ‘null modal’, and to offer such a treatment.

Loosely, what I mean by counterfactual mood is mood or tense marking that causes the clause it appears in to imply the negative of some type t constituent, or more briefly, to license an inference of counterfactuality. The term ‘X-marking’ as used by von Fintel and Iatridou (2023) has a roughly matching intended reference (see Sect. 2.2), so I also use that, along with ‘X mood’ or just ‘X’.

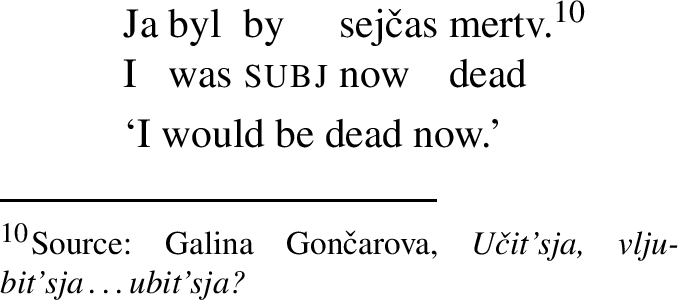

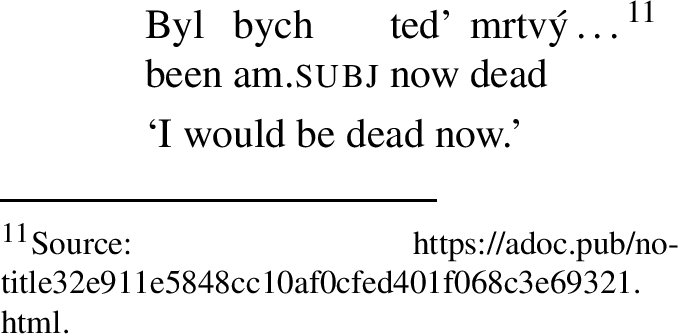

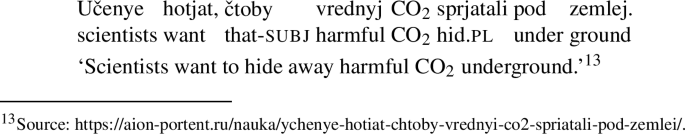

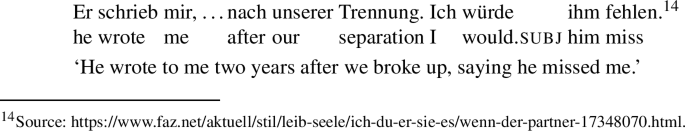

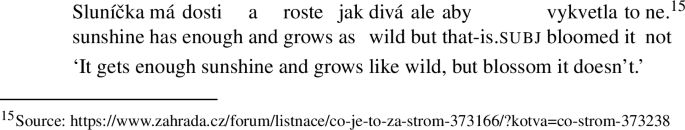

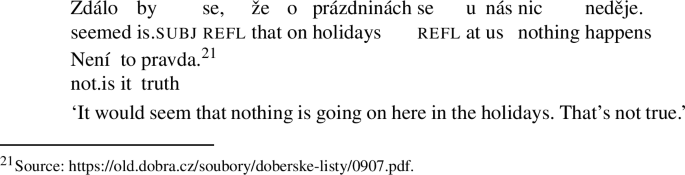

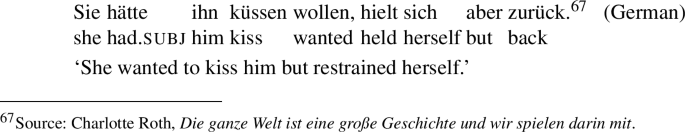

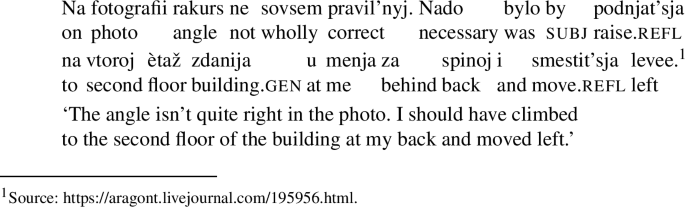

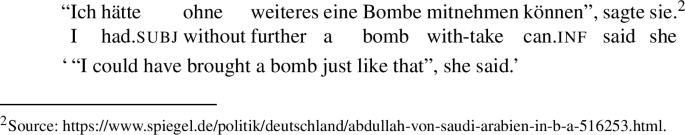

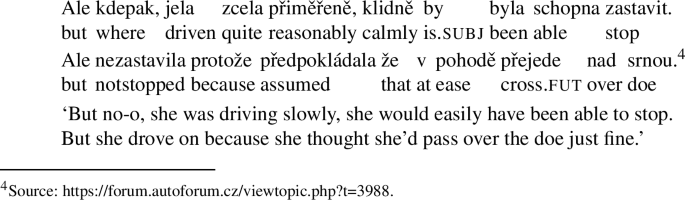

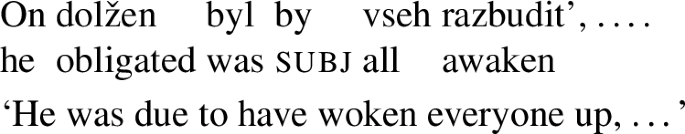

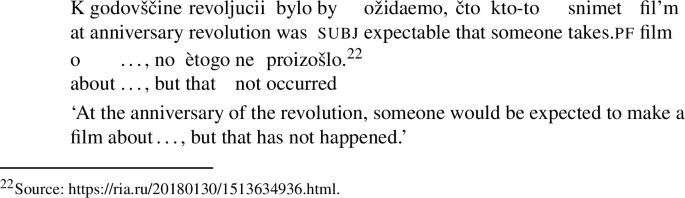

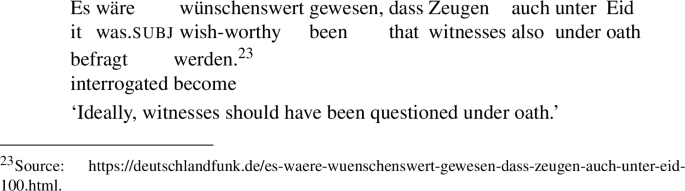

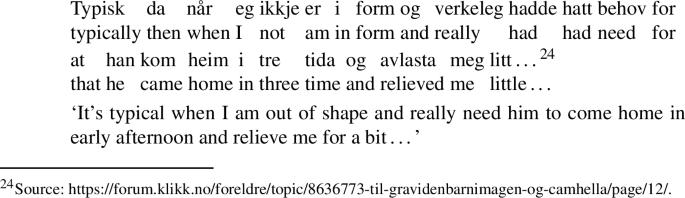

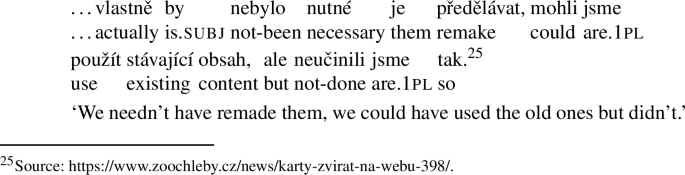

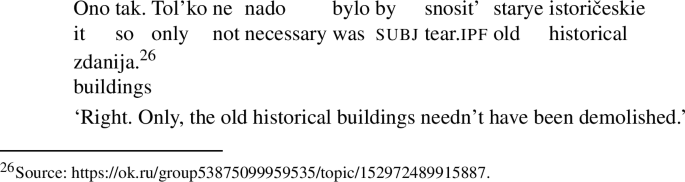

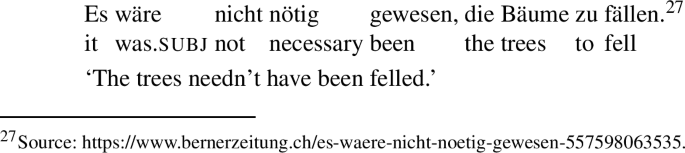

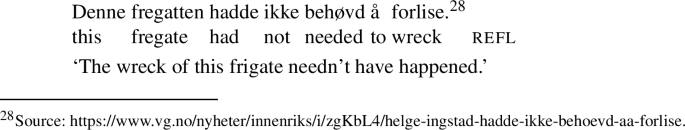

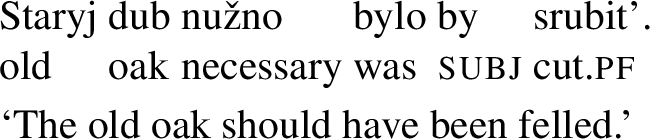

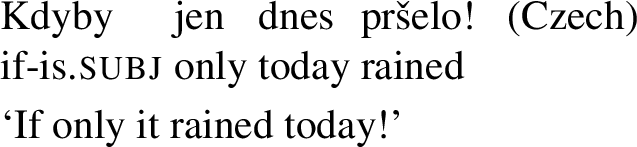

Some illustrations are in order. Although conditionals are a core context for it, counterfactual mood is also often found in overtly modalized sentences without a conditional structure. Below are four examples, from Russian, German, Norwegian and Czech, respectively, with necessity (1)–(3) and possibility modals (2)–(4) and with teleological (1)–(3), metaphysical (2) and dispositional (4) modal flavors.

-

(1)

-

(2)

-

(3)

-

(4)

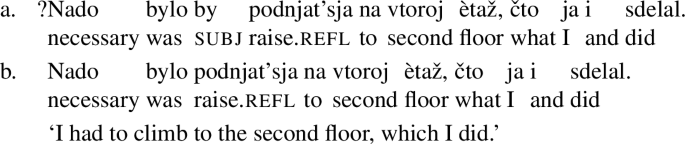

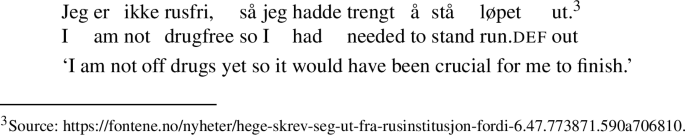

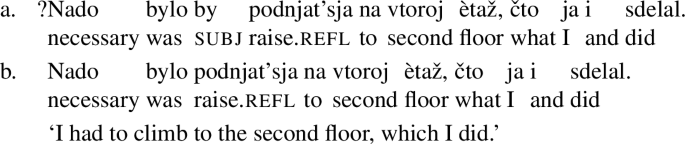

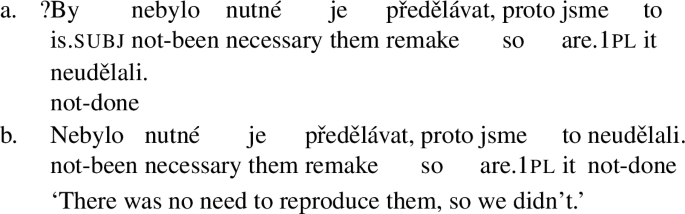

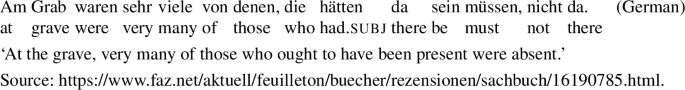

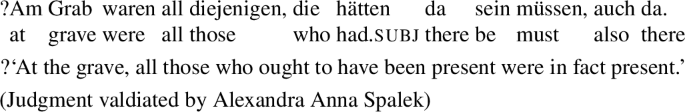

In each case here, with certain caveats (see below), the modalized sentence licenses the inference that the prejacent is false. For one thing, the broader contexts make it clear that, for instance, I did not climb to the second floor of the building, et cetera. To be sure, that does not yet show that the sentences license those inferences. But secondly, speakers of each language report that unlike the sentences without the X marking (coming from (1), say, by removing the subjunctive marker by), (1)–(4) are or can be incompatible with continuations like ‘…which I did’. Sentences like (1-a) are thus read as potentially contradictory while sentences like (1-b) are not:

-

(1)

Two caveats are in order. First, for speakers of Russian and partly of Czech, (1-a) or sentences patterned on it are not unconditionally odd; some Czech speakers report that the continuation—at any rate if it contains a word like taky ‘too’—can cancel a counterfactual inference they would otherwise draw from the first sentence half, and for speakers of Russian, this half can have a past futurate reading without any counterfactual implication.Footnote 1 Second, a counterfactual inference will only be drawn when the speaker can be assumed to know whether the modal’s prejacent is true.

Bearing these qualifications in mind, a common denominator seems to emerge despite the variation in morphology and in forces and flavors of modality across (1) through (4): a use of subjunctive mood or past tense that can, and will in the right circumstances, make modalized sentences convey a counterfactual meaning.

There are various approaches to such a use, particularly targeting conditionals, but on all existing proposals that are formally explicit (see Sect. 4), the X mood, whether it spells out as a subjunctive or as a ‘fake’ past tense, or as a combination, is taken to operate on a proposition or to introduce a presupposition, or both, or it is taken to convey an antipresupposition. They all, therefore, are faced with at least one major challenge, from one or both of these two observations:

-

(1)

The mood marking is sometimes not in the clause expressing the proposition that the counterfactual inference concerns but in a matrix clause.

-

(2)

The counterfactual inference sometimes turns into a factuality inference, essentially in negative contexts.

1 is challenging for any theory that lets the mood operate on a proposition, and 2 is for any theory that ascribes a presupposition to it.

The theory I propose does neither. Set within the framework of alternatives and exhaustification advanced by Chierchia (2013), it can be summarized like this:

-

The mood operates on meanings of modals, monadic propositional operations,and its ordinary semantic value is the identity function on such arguments.

-

At the same time, it activates alternatives: its alternative semantic value contains the function that maps any propositional operation to the identity operation.

-

Through exhaustification at some type t level, the alternative here—usually the argument proposition of the mood-modified modal—gets its negation added to the ordinary semantic value as a ‘grammatical’ implicature of counterfactuality.

-

However, if exhaustification applies to a negative context, the alternative is itself negative, resulting in an implicature of factuality.

The first two points state, by stipulation, the semantics of the counterfactual mood—its ordinary and alternative semantic values. That much is new, but the rest is old: the latter two points follow from the meaning of the mood in conjunction with the general theory of alternatives and exhaustification.

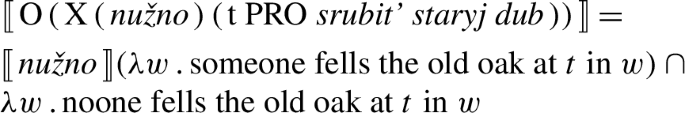

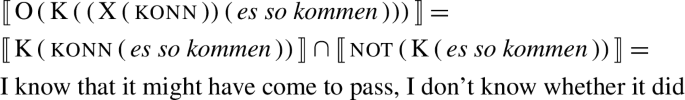

The third point sets out, in a nutshell, how the counterfactuality inference comes about: once activated, alternatives must be factored into meaning, and with the O (for ‘only’) exhaustifier, also called Exh, this operation results in an added conjunct not ϕ where ϕ is usually the argument of the modified modal. Schematically:

-

(5)

.

Note that mood(modal) and ϕ can be expressed in two different clauses, the former in a matrix and the latter in a constituent clause; this explains observation 1 above: the mood can be marked ‘upstairs’ while the counter-fact is expressed ‘downstairs’. Note, too, that if, say, a negation intervenes between o and o(mood(modal)(ϕ)), the added conjunct will not be not ϕ but not(not ϕ), that is, ϕ; this, the fourth point, explains observation 2—the mood can cause a factuality inference.

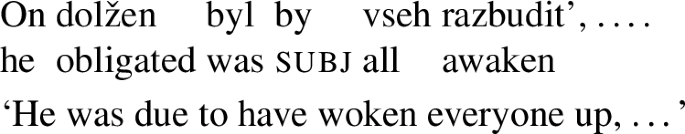

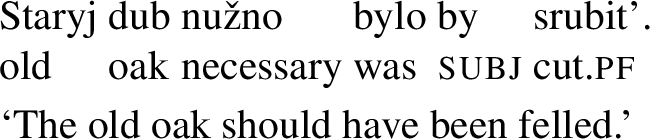

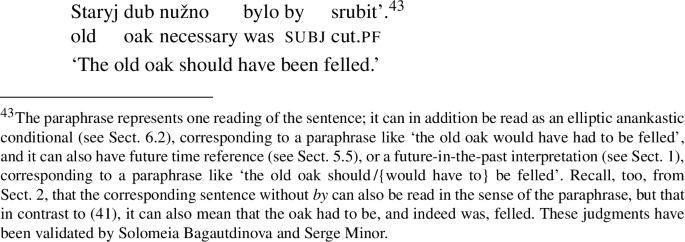

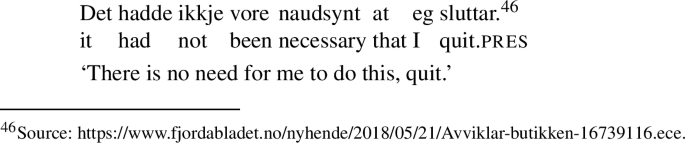

As a simple instance of the schema (5), consider the Russian sentence (6), cited by Dobrušina (2016, p. 146f.) and replicable in Czech, German and Norwegian:

-

(6)

According to Dobrušina, in contrast to the sentence without the subjunctive particle by, (6) entails on ne razbudil ih—‘he failed to awaken them’. With reference to (5), mood = by, modal = dolžen ‘due’, and ϕ= on vseh razbudil ‘he woke everyone up’. o, finally, is assumed to be covertly present in a position at the top level of (6) and to contribute the negation of the alternative—ϕ—to the meaning of the sentence.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 brings preliminary clarifications in two key regards: first, regarding the formal means of signaling counterfactuality in the four languages in focus and their functions beyond signaling counterfactuality, second, regarding the signs by which to tell the counterfactual mood of a language from other uses of the same formal machinery, and a working definition.

The evidence underlying observations 1 and 2 is presented in Sect. 3, and in Sect. 4, this evidence is shown to constitute, in one way or the other, challenges to previously proposed accounts of the counterfactual mood. The alternative, novel account is developed in Sect. 5 and shown to produce precise predictions for the problem cases from Sect. 3, and in Sect. 6, predictions for counterfactuals are explored and shown to be adequate as well. Section 7 addresses some challenges to the theory and brings conclusions.

2 Counterfactual mood: preliminaries

The four languages Czech, Russian, German and Norwegian were selected for study because they show a spread in how counterfactual mood is expressed and in how the same expression can also be used to express a non-counterfactual mood. These variations are described in Sect. 2.1.

It is also useful to have as accurate a sense as possible of what a counterfactual mood is and of what distinguishes it from other uses of subjunctive or ‘fake past’ in one or the other of the four languages. Section 2.2 brings a discussion of how to single it out, coalescing into a working definition.

2.1 Mood in the four languages, forms and functions

The following overview of the morphology of counterfactual mood and of its place in the functional field of mood across the four languages is based, in particular, on three monographs: Bech (1951) (in regard to Czech), Fabricius-Hansen et al. (2018) (in regard to German), and Dobrušina (2016) (in regard to Russian).

2.1.1 Forms

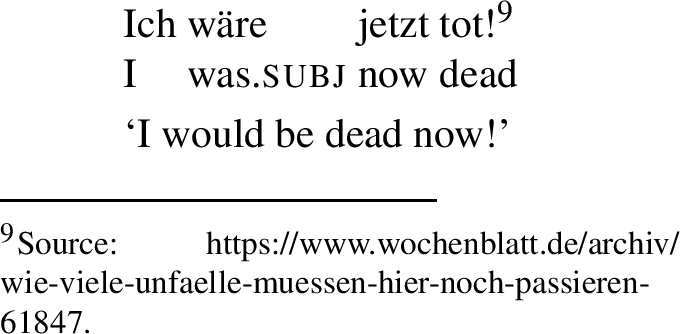

Morphologically, Norwegian stands out among the four languages in that it has no subjunctive, leaving auxiliaries and fake tenses, such as pluperfects in both present and past time contexts, as the regular means of encoding counterfactual inferences. German, Russian and Czech have subjunctives which can encode counterfactuality, but the subjunctive manifests itself differently in the three languages:

-

in German, as the umlaut stem of one of several auxiliaries or a few main verbs,

-

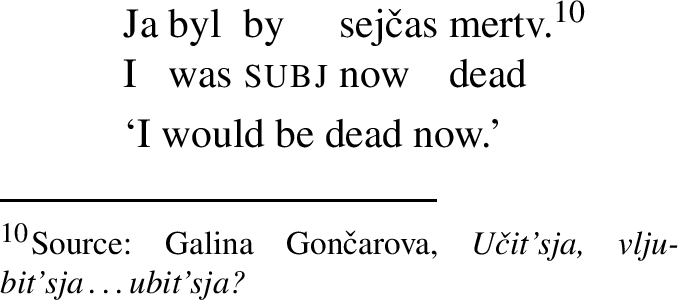

in Russian, as the particle by, which can cliticize to the ‘that’ complementizer čto,

-

in Czech, as the by(-) stem of the auxiliary být ‘be’, which combines with perfect participles and can help form the declarative clause complementizer aby(-) or the conditional clause complementizer kdyby(-) (see Hana 2007, p. 81).

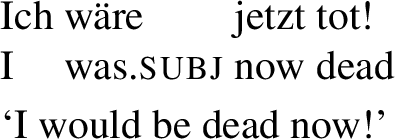

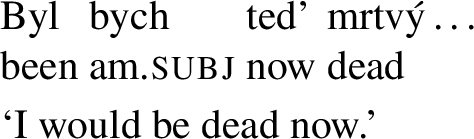

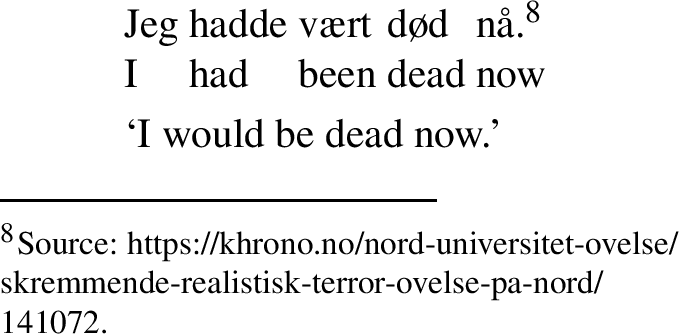

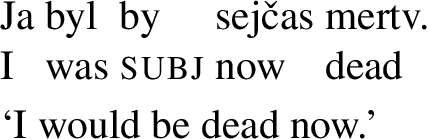

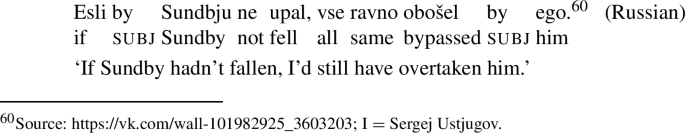

(7)–(10), in Norwegian, German, Russian and Czech, respectively, may illustrate:Footnote 2,Footnote 3

-

(7)

-

(8)

-

(9)

-

(10)

As far as the counterfactual use is concerned, this subjunctive marking is regularly accompanied by some form of past tense which may well be ‘fake’ (Iatridou 2000). In Russian and Czech, past forms of verbs, simple in Russian, periphrastic in Czech, are used in past and present contexts,Footnote 4 in German, past (or past perfect) forms are used in present contexts and past perfect forms are used in past contexts.

2.1.2 Functions

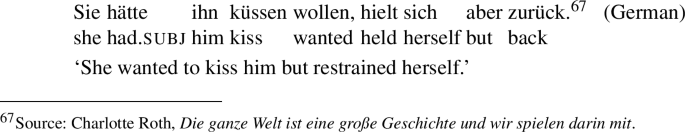

The subjunctive-cum-fake-past forms found in Czech, German and Russian are not uniform functionally but serve other functions than marking counterfactual mood as well. Notably, these other functions are different in the three languages:

-

In Czech and in Russian, the subjunctive is prominently used in purpose clauses and in ‘purpose-like’ complement clauses (Dobrušina 2016, p. 263ff.; Sočanac 2017). These uses are closely akin to the ‘intensional’ subjunctive in Romance languages (Stowell 1993; Quer 1997). They are often described in terms of matrix predicates ‘licensing’ or ‘selecting for’ subjunctive complements, for example, Czech chtít or Russian hotet’ ‘want’, as in (11) below.

-

In German, there is instead a prominent use of the subjunctive in reported speech (Fabricius-Hansen et al. 2018, p. 105ff.), exemplified in (12) below.

-

All three languages exhibit a ‘polarity subjunctive’ usage closely akin to the uses of Romance subjunctives designated by this term (Stowell 1993; Quer 1997)—see Bech (1951, p. 45ff.), Dobrušina (2016, p. 242ff.), Kagan (2013, p. 133ff.), Fabricius-Hansen et al. (2018, p. 62ff.), Sæbø (2023)—and exemplified in the Czech sentence (13) below.

-

(11)

-

(12)

-

(13)

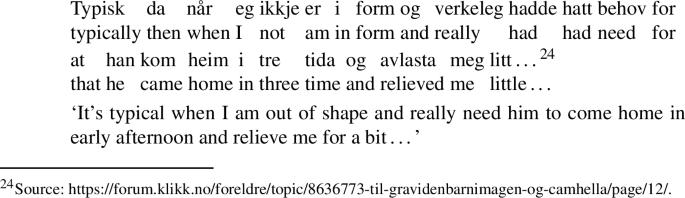

In Norwegian, fake past tenses generally signal counterfactuality.

2.1.3 Form - function association

It is clear from the preceding that there is no one-to-one association between forms and functions as regards counterfactual mood and its marking in a given language. The relation may best be thought of in terms of a many-to-many mapping between bundles of features (such as X and present) and bundles of formal elements (such as subjunctive and preterite) which can be their exponents. The Norwegian pluperfect, say, maps to past-and-past, to X and present, or to X and past.

According to this way of thinking, there is counterfactual marking, X-marking, on the one hand, and there is counterfactual mood, X, on the other hand; the former consists of language-specific formal elements which can also mark other things, and the latter is a language-invariant, interpretable feature, to be assigned an interpretation in Sect. 5.2 (see Sect. 5.4 for a more elaborate outline of its syntax). Sometimes the term ‘morpheme’ is used for X in the same sense as ‘feature’.

The term ‘(counterfactual) mood’ is here used in the sense of such a feature, not as a name for a language-dependent morphology. It may be questionable to use the term in this way, not least in regard to a subjunctive-less language like Norwegian. The reason I still do so is twofold: first, because in each of the four languages which has a morphological subjunctive mood, the X feature has it as an exponent; second, because counterfactuality is one kind of meaning which has traditionally often been associated with subjunctive mood.

As for the other kinds of meaning that can be marked by subjunctive forms in Czech, German and Russian, reviewed in Sect. 2.1.2, the analysis of the X mood that is proposed in Sect. 5 cannot be expected to extend to those functions. The working assumption is that subjunctive markings are ambiguous, but properly arguing for this assumption lies beyond the scope of the present paper.

2.2 Delineation and a working definition

What I mean by counterfactual mood is something relatively strong: standardly, it causes the sentence to license the inference that a constituent sentence is false. The term ‘irrealis’ has been used in roughly this sense (see, e.g., Csipak 2015, p. 19ff.), but for the most part it is, particularly in the typological literature, used in a much wider sense, more or less synonymously with markings of non-veridicality; see the discussion in, e.g., Mithun (1995). In the present context, by contrast, what is at issue is what von Prince et al. (2022) call the counterfactual domain of irrealis.

Against this background, I will presently delineate the notion of counterfactual mood and supply some clues for recognizing it when it appears.

As a matter of fact, counterfactual mood coincides reasonably well with what is traditionally called the ‘independent’ subjunctive (Bech 1951, p. 18f.; Dobrušina 2016, p. 29ff.; Fabricius-Hansen et al. 2018, pp. 34, 41), as opposed to uses of subjunctives which are conditioned by some certain kind of context, mostly a matrix clause predicate, where subjunctive may be the only possible mood, or where indicative and subjunctive are interchangeable. By contrast, when subjunctives occur independently, they make a difference: indicative can be substituted, but as a rule, the meaning will be affected.

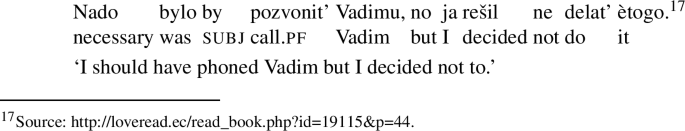

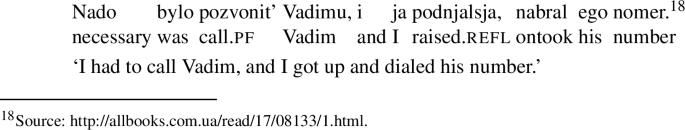

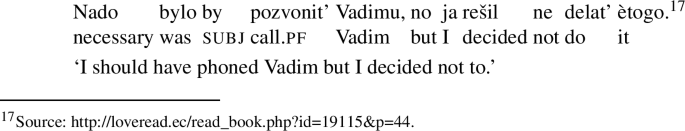

In what can be called standard cases, the difference made by the counterfactual mood is an added counterfactual implication concerning the argument proposition of a modal operator, where ‘modal operator’ can be taken in a wide sense, including conditional operators and propositional attitude predicates. This added implication can be illustrated for a narrow-sense modal operator by the Russian sentences (14) and (15), a near-minimal pair where only the first member features the subjunctive. (14) licenses the inference that I did not call Vadim, while (15) licenses the inference that I did call Vadim. And although the first clause in (15), without the particle by, is also compatible with a context in which no call was made, the first clause in (14), with the by particle, is only compatible with a context where no call was made.Footnote 5

-

(14)

-

(15)

Thus due to the mood, one can infer that the modal’s prejacent is contrary to fact. Note that the time reference is here past, and that the modality is of the root kind; in fact, non-future temporal reference and root modality can be considered typical features of standard cases of the counterfactual mood.

von Fintel and Iatridou (2023) focus on three environments for X-marking:

-

conditionals,

-

desire constructions,

-

necessity modal constructions.

All three of these environments involve modal operators in the wide sense, and so in principle, they all fall within the scope of the standard cases outlined above. (14) is a necessity modal construction, as are (1), (3) and (6); desire constructions are illustrated with (19) in Sect. 3.1 and discussed on the basis of (89) in Sect. 7.2; and conditionals are illustrated and treated in Sect. 6.

In connection with necessity modals, von Fintel and Iatridou (2023, p. 1492) note that in many languages, X-marking appears to make weak ones out of strong ones. This observation cannot readily be corroborated by data such as (1), (3), (6) or (14), or more generally based on Czech, German, Norwegian or Russian cases with past or present time reference. What is observable, and is discussed in Sect. 5.5, is a weakening of the counterfactual inference in cases with future time reference. Since the examples of weakened necessity offered by von Fintel and Iatridou (2023) are future-oriented, the two effects might be related. In any case, the present work does not aim to account for any necessity weakening effects, its main aim being to give an account of counterfactuality effects. Since these effects are relatively weak in future contexts, there is reason to consider such contexts as non-standard cases, along with three others where a counterfactuality effect is less clear or absent:

-

(1)

the case where the counterfactual inference switches to a factual inference in a negative context; see Sect. 3.2,

-

(2)

the case where the inference, be it counterfactual or factual, is overridden by a conflicting entailment or presupposition and fails to materialize,

-

(3)

the case where the speaker cannot be taken to have a belief about the truth value of the proposition, or where such a belief is not relevant.

That these cases are considered ‘non-standard’ does not mean that they are not to be accounted for: for 1, see the account in Sect. 5.3.2; for 2, see Sects. 5.3.2 and 6.3; for 3, see Sects. 5.1 and 5.5; and for future time cases, see Sect. 5.5.

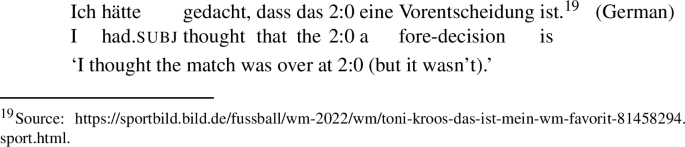

Returning to standard cases and the generalization over them made above, rendered in a concise form in the below working definition, it may be noted that much more falls under it than the three environments focused on by von Fintel and Iatridou (2023). In particular, alongside necessity modal constructions, we find possibility modal constructions, both with a wide range of root modal flavors; over and above desire constructions, we find a broad array of non-factive propositional attitudes, including—pace von Fintel and Iatridou (2023, p. 1498)—beliefs:

-

(16)

Across all these constructions and in conditionals, we find ‘standard cases of X’—i.e., of counterfactual mood—constituting the prime data to be accounted for:

-

One of the ways of marking X surveyed in Sect. 2.1.1 does in fact mark a standard case of X iff it causes the construction to license the inference that the argument proposition of the relevant modal operator is not true.

3 Two challenging observations

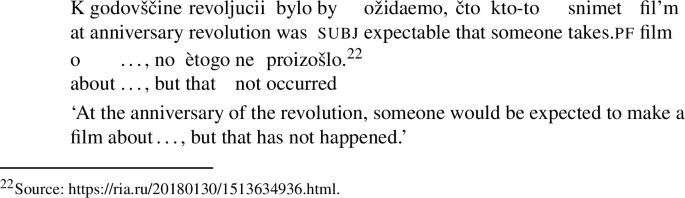

This section presents and discusses two facts about counterfactual mood marking in the four languages under consideration, facts which constitute major challenges to existing analyses of counterfactual mood. First, any theory that places the mood at a clausal level (the level of TP, say) and takes it to operate on propositions will be hard put to account for the fact that the marking often appears in a matrix (and sometimes only there) while the ‘counterfact’ is expressed in a complement clause. Second, any theory where the counterfactual inference is a presupposition faces a challenge in the fact that it can turn negative in contexts of negation.

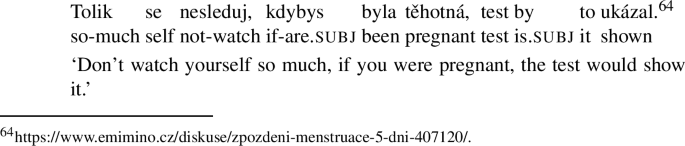

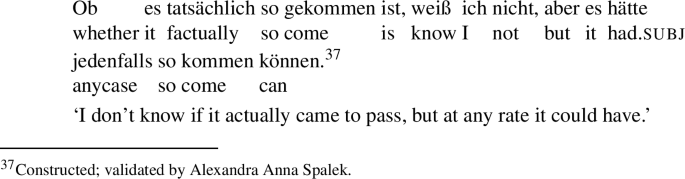

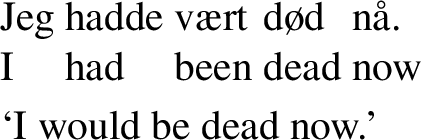

3.1 The mood in the matrix

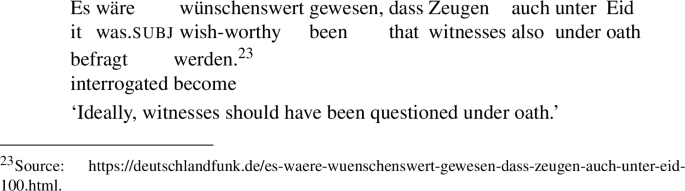

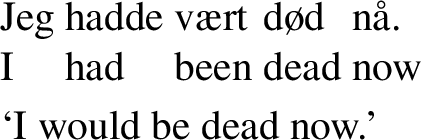

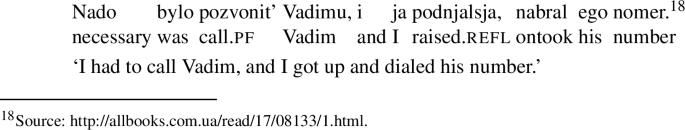

(17)–(20) all license a counterfactual inference, but this inference does not concern the proposition expressed in the clause where the subjunctive or fake past (perfect) occurs—it concerns the proposition expressed in a complement clause. Thus in the Czech example (17), it is the matrix clause that shows past subjunctive morphology—the constituent expressing the ‘counterfact’ shows present indicative morphology. The same holds true of the Russian (18) and the German (19). The Norwegian (20) has a fake past in the embedded clause, but the matrix has a fake past perfect.Footnote 6

-

(17)

-

(18)

-

(19)

-

(20)

This poses a problem for any theory that seeks to attach a counterfactual inference, however strong or weak and in whatever way, to a proposition taken as the mood’s argument. From such theories, one would expect a counterfactual inference for the matrix clause in each of the examples: such-and-such does not seem to be the case, is not to be expected, or wished, or is not something I need to be the case. And sure, a counterfactual inference is there, but it affects the subordinate clause.

It might be thought that there is a sense in which the content of the matrix is, in (18) and (19), implied to be false after all: any expectation, or wish, would be, as it were, thwarted, or vain, and so not truly entertained or worth entertaining—the counterfactuality of the embedded content could be seen as a consequence of that. But this reasoning can hardly be extended to (17) or (20), where the semblance and the need are real enough.

The fact that mood marking can be ‘upstairs’ while its effect is ‘downstairs’ does not necessarily pose a problem for approaches where the mood manipulates a modal or a modal’s restrictor (see Sect. 4). The reason is that in each case above, the downstairs proposition is the argument of a modal operator upstairs; if modal operators are arguments of the mood, it is natural that the mood is upstairs too.

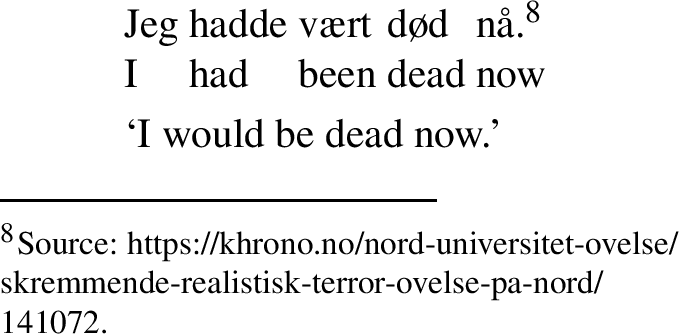

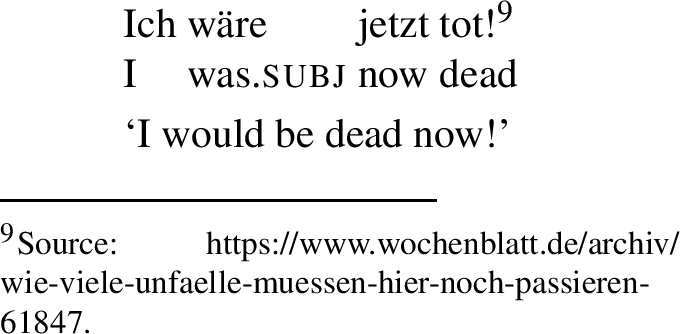

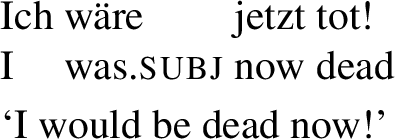

3.2 Counterfactual inferences turn into factual inferences

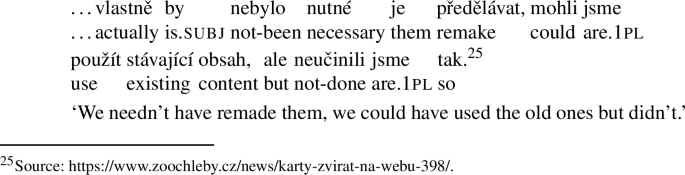

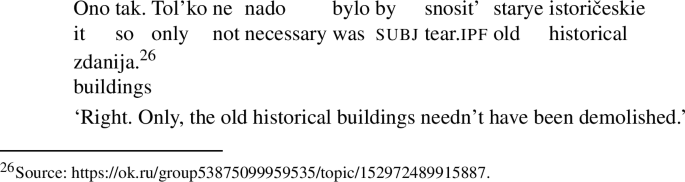

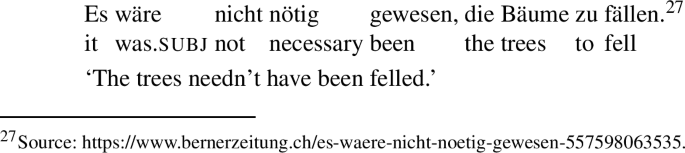

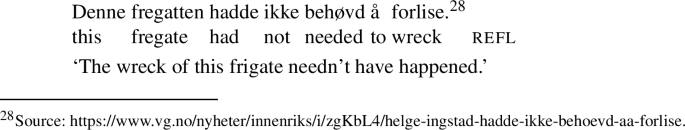

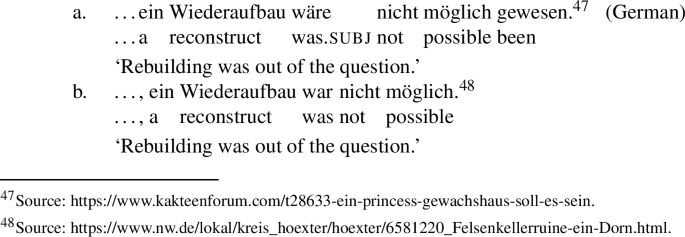

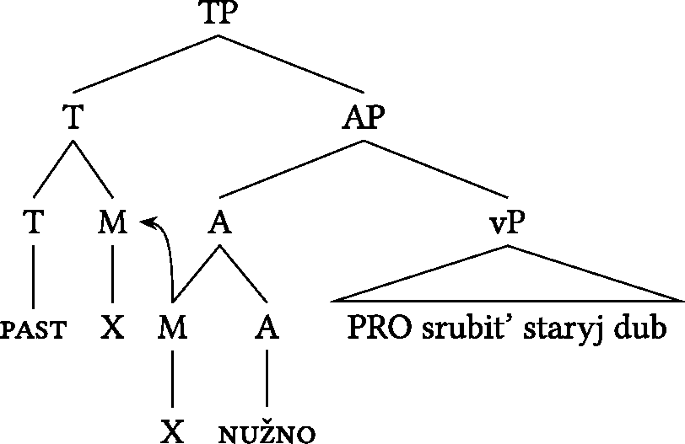

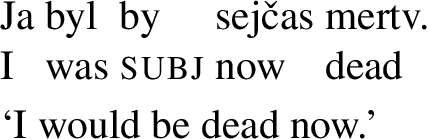

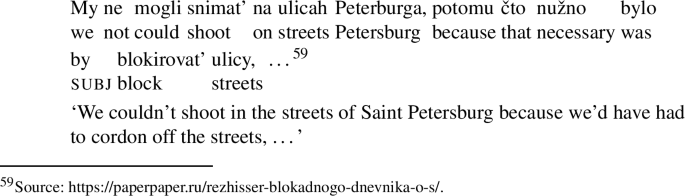

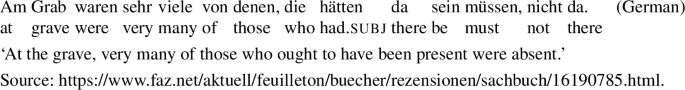

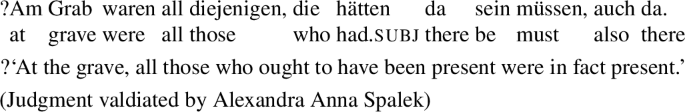

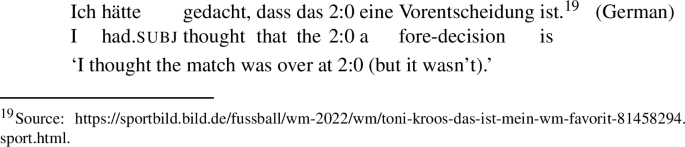

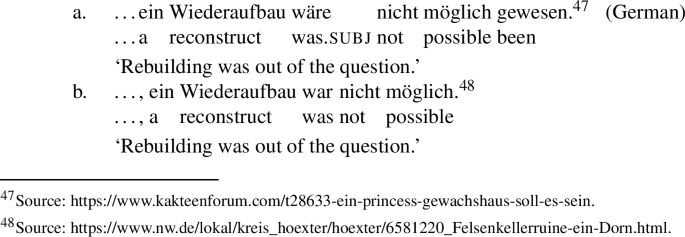

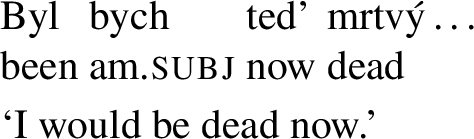

In negative contexts, mood-made counterfactuality inferences are switched around to become factuality inferences. This effect can be observed in the following cases, in Czech, Russian, German and Norwegian, respectively, with necessity modals where the wider contexts show that the modal bases are circumstantial and the ordering sources are teleological (in (21)–(23)) or metaphysical (in (24)):

-

(21)

-

(22)

-

(23)

-

(24)

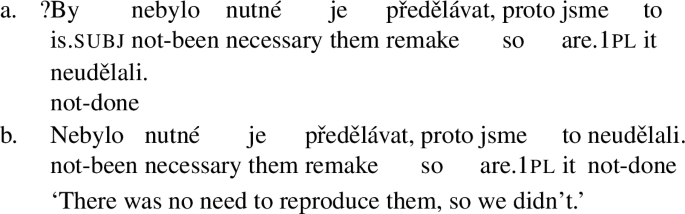

Consultants report that in contrast to the corresponding non-X-marked sentences, (21) through (24) are incompatible with continuations like ‘…, so we didn’t’, thus—with the same caveats as noted in connection with cases like (1-a) in Sect. 1—sentences like (22-a) are felt to be contradictory, while ones like (22-b) are not:Footnote 7

-

(22)

The corresponding non-negative sentences will license counterfactual inferences.Footnote 8 This shows that the inference associated with the X mood is sensitive to negation. That is problematic for any analysis which ascribes a counterfactual presupposition to the mood, as any presupposition would be inert to a negation, projecting past it. A treatment in terms of implicatures is a better fit for these data; see Sect. 5.3.2.

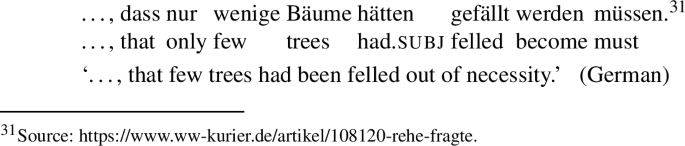

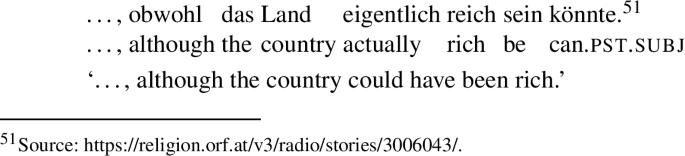

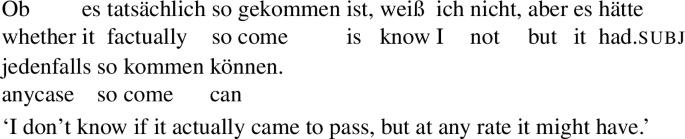

The observation that counterfactual inferences turn factual in negative contexts can be generalized to say that downward entailing inferences in upward entailing contexts turn upward entailing in downward entailing contexts. Consider (26).

-

(26)

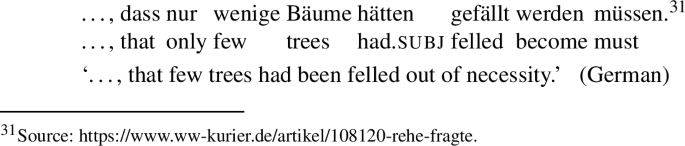

The context is a story on a controversy over the logging of trees along a bike trail, argued to have been necessary for safety reasons because many trees were rotting, but also criticized as excessive because a lot of stumps showed no evidence of rot. (26) is a downward entailing context which licenses an upward entailing inference: that not just a few trees were felled, but many.

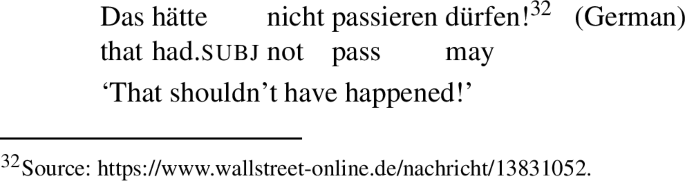

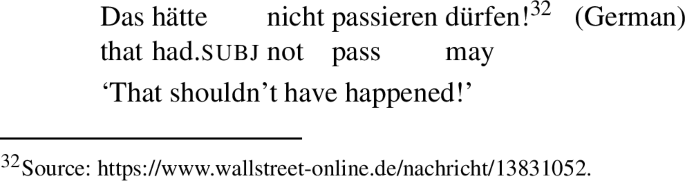

It may seem conspicuous that all five of the above examples involve necessity modals. Indeed, when possibility modals have realistic conversational backgrounds (as when the ordering source is empty), factual inferences will contradict the main, at-issue content of the sentence—as p will contradict ¬◊p—and fail to materialize. However, when a possibility modal has a normative or teleological ordering source, a factual inference will be consistent with the negative sentence and will surface—as in (27), which licenses the inference that an event of the type referred to by the pronoun das ‘that’ has in fact occurred.

-

(27)

The theory laid out in Sect. 5 brings out why factuality inferences fail to surface when they would conflict with the main content of the negated sentence: there are no ‘innocently excludable alternatives’ to be (doubly) negated.

4 Previous proposals and their problems

Let us now examine how existing analyses are equipped to deal with the facts that have been identified. All of them face challenges: some, because the mood is taken to operate on propositions; others, because it is taken to trigger a presuppositon or an antipresupposition; others yet, because they leave it unclear how a counterfactual inference can arise.

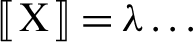

It may be noted that many proposals are tailor-made for English ‘subjunctive’ conditionals, and also that few are worked out in formal and compositional terms, as definitions of the meaning of the X mood which could be written on this form:

-

(28)

Still, as shown below, some proposals which have been made for conditionals can be generalized to fit other contexts too, and some which have not been articulated formally may lend themselves to such an articulation.

4.1 The argument is a proposition

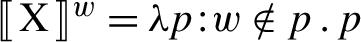

There are two lines of analysis where the X mood operates on a proposition. In one line, the mood denotes a partial identity function, undefined for propositions that contain the world of evaluation—alternatively, as the case may be, for propositions that intersect with the context set, or the epistemic state of the speaker, or the like. In the simplest case, this line of analysis can be formalized as in (29):

-

(29)

The definition of counterfactual mood provided by Grosz (2012, p. 168) in his work on optative clauses is representative here: MoodCF introduces the presupposition that p, the argument proposition, has no overlap with the speaker’s epistemic state. On a similar note, in work on Spanish, Vallejo (2017, p. 51) equips the ‘modal past’ with the presupposition that the world of evaluation is not among the topic worlds, the intersection between the argument proposition and the modal base worlds.

On the other line of analysis, the mood will output the proposition that differs from the input by being undefined or false at, in the simplest case, the index world:

-

(30)

The definition of the English simple past (ESP) provided by von Prince (2019, p. 593), building on Iatridou (2000), may serve as an example: ESP takes a relation between worlds and times and restricts it so that (i) the times are prior to the utterance time or (ii) the worlds differ from the utterance world. This latter ‘world case’ amounts to filtering out the actual world from the argument proposition.Footnote 9

On either line, the assumption that the mood has a proposition as its argument makes any analysis poorly equipped to explain the fact—established in Sect. 3.1—that a counterfactual inference can concern a proposition expressed in a clause under the clause where the mood is situated. The reason: any counterfactual inference will be predicted for the argument proposition of the mood, in these cases, the proposition expressed in the super-, not the subordinate clause.

4.2 The upshot is a presupposition

That challenge does not face lines of analysis where the X mood takes other things than propositions as arguments, such as worlds or propositional operations. Quite a few proposals are of this kind, at least once they are made compositionally precise. Most, however, are faced with another challenge: they tend to model the meaning contribution of the mood as a presupposition, thus predicting a projection pattern in conflict with the facts from Sect. 3.2.

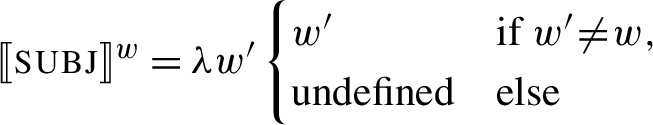

On a common view of ‘subjunctive conditionals’, they are counterfactuals and “presuppose that their antecedent is false” (von Fintel 1998, p. 29); Lakoff (1970, p. 177) is one example. Schlenker (2005, p. 279) offers an ingenious implementation of this idea, letting the English ‘subjunctive’ apply to a world and introduce the presupposition that this world differs from (or ‘is more remote than’) the world of evaluation.Footnote 10

-

(31)

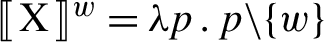

This analysis is based in the analysis of conditionals proposed by Schlenker (2004), where an if clause denotes a possible world, the closest to the world of evaluation where the antecedent is true; when \(w^{\prime }\) is that world, (31) amounts to presupposing that the antecedent is not true in the world of evaluation.

The assumption that the antecedent is presupposed to be false has been argued to be too strong, and weaker presuppositions have been proposed by Schulz (2014) and Mackay (2019), building on von Fintel (1998).Footnote 11

(32) is a compositional formulation of this latter proposal. The X mood operates on a binary propositional operation, adding the presupposition that C, the context set, is a proper subset of the intersection over \(f_{w}\), the modal base.

-

(32)

In other words, the modal base for the modal which serves as a conditional operator extends beyond the context set—which is a version of the ‘domain widening view’ advocated by von Fintel and Iatridou (2023, p. 1476ff.).

Both von Fintel (1998) and Mackay (2019) only have conditionals in mind, and (32) is tailored to dyadic modal meanings as arguments of the mood, but it is fully possible to modify (32) to cover the case of monadic modal meanings:

-

(33)

In any case, however, the assumption that the mood introduces a presupposition, be it strong or weak, makes any of the analyses considered here an unpromising point of departure for a general theory of counterfactual mood. The reason is that we would expect the presupposition to persist in a presupposition hole context like a negative context—and as we have seen in Sect. 3.2, a counterfactual inference can change its sign in such a context, from counter- to factuality.

An analogous challenge faces the approach that appeals to antipresupposition. Leahy (2018), building on Stalnaker (1975), attributes to indicative conditionals the presupposition that the antecedent is epistemically possible and derives its reverse as a ‘presuppositional implicature’ for subjunctive conditionals. Though there may be good reason to view counterfactual inferences as antipresuppositions, since the projection behavior is commonly assumed to mimic that of presuppositions proper (see Bade 2021), the choice hardly matters for the facts set out in Sect. 3.2.

4.3 Taking stock

The explicit analyses of the X mood that have now been reviewed, if only cursorily in some cases, exhaust the field of what is currently on the market. This means that every existing explicit analysis makes mood a function from propositions or it models its meaning as a(n) (anti)presupposition, or both, and either property places it at a disadvantage if it is to account for cases like those focused on in Sect. 3.

A word of caution is in order. Most of the proposals are meant for conditionals, and their failure to generalize to cases like those considered in Sect. 3, with unary modals or propositional attitudes, cannot be held against them. But the bottom line is that none of them can be readily and successfully extended to such cases.

It is also notable that several proposals—like those made by von Prince (2019) or Mackay (2019)—do not themselves predict counterfactual inferences; when in evidence, those must be derived by some auxiliary mechanism (von Prince 2019, p. 603 thus attributes counterfactuality to a Quantity implicature). This is not accidental; in the face of conditionals that do not license such inferences (see Sect. 6.3), it has seemed prudent not to make too strong predictions.

But the challenge is then to account for the inferences that sometimes do arise. von Fintel and Iatridou (2023), who advocate a weak meaning—X marking signals that the modal base goes beyond the default domain—without committing to how this meaning is encoded, present “the derivation of the counterfactual inference” as an open issue. Quite by contrast, the analysis proposed in the next section derives the counterfactual inference by default, and the cases that have motivated the weak analyses come out as instances of exceptions that are built into the theory.

5 The novel move: the mood modifies modals

This section sets out an account of counterfactual mood that meets the challenges identified in Sect. 3. It is rather different from any existing account, yet it shares features with two of the approaches to this or similar morphemes surveyed above, firstly, regarding the scope and secondly, regarding the effect of the mood:

-

It develops further the outlook of von Fintel and Iatridou (2023) on X-marking to let the mood operate on the meaning of any modal,

-

it has in common with the view of von Prince (2019) on the modal past tense that the mood is taken to give rise to an implicature.

Section 5.1 lays some groundwork for the account in relatively informal terms, Sect. 5.2 supplies formal definitions and the derivation of a simple paradigm case, and Sect. 5.3 shows how the two ‘problem cases’ considered in Sect. 3 are not problematic but predictable on this account. Sections 5.4 through 5.6 offer thoughts on (i) the morphosyntax of the mood, (ii) the robustness of the implicature, and (iii) the possible positions for the exhaustification operator.

5.1 Counterfactual inferences as implicatures

The leading idea is that the mood activates alternatives to the modal it operates on, particularly one: the ‘null modal’, denoting the identity function over propositions; exhaustification with respect to this alternative results in an implicature which co-incides with the counterfactual inference.

The status of this inference is thus as a conversational implicature, specifically, within the ‘grammatical theory’ of such implicatures (see e.g., Chierchia et al. 2012). This has clear advantages, as a range of observations made about the inference can thereby receive an explanation; an overview is given in Sects. 5.1.1 through 5.1.4.

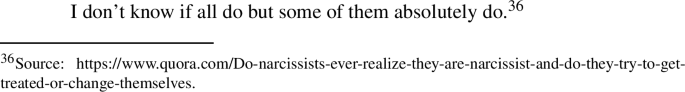

5.1.1 Cancelation

As noted in Sect. 1, an X-marked sentence may on its own have a counterfactual implication, yet for some speakers, a continuation that contradicts that implication is still felicitous, at least if it includes a signal of awareness—like ‘in fact’ or ‘too’—that the second sentence goes against what has been implied by the first sentence. This is consistent with a notion of the counterfactual inference as a conversational implicature, as such inferences are generally viewed as cancelable, and cancelation is typically accompanied by signals like ‘in fact’ (see Mayol and Castroviejo 2013).

5.1.2 The well-informed speaker

As was also noted in Sect. 1, some report that the counterfactual inference is not licensed if the speaker of the sentence may be ignorant of whether it is true or not. Such a dependence on what has been labeled the Opinionated Speaker assumption is a prominent hallmark of conversational implicatures. (34) illustrates its relevance for scalar implicatures, and the German example (35) shows that it is also relevant for the counterfactual inference:

-

(34)

-

(35)

In both cases, the first sentence states that the speaker is ignorant about the truth or falsity of the putative inference, which does not then come about. The observed weaker counterfactual inference in sentences with future reference (see Sect. 2.2) can be thought of in similar terms—more about this in Sect. 5.5.

5.1.3 Reinforceability

Another hallmark of conversational implicatures, particularly scalar implicatures, is that they can be, and often are, reaffirmed in the immediately subsequent discourse. Such a continuation is regularly accompanied by an adversative marker.

The counterfactual inferences under consideration share this property too. (36) illustrates it in connection with a scalar implicature, and the German example (37) demonstrates how a counterfactual inference can show a parallel behavior:

-

(36)

-

(37)

It may seem paradoxical that a contrast is marked, with but or aber or the like, between a sentence licensing a certain inference and the sentence expressing that very inference. But this is in fact the pattern we find whenever a scalar implicature is made explicit in a continuation—as it is in (36). And under an alternative-based, anti-additivity analysis of adversative markers (see Sæbø 2003; Umbach 2004), such markers are predicted to be felicitous in just such contexts as (36) or (37).

5.1.4 Excludability

Sometimes, the counterfactual inference is missing even though the speaker can be assumed to be well-informed. Under an analysis of it as an implicature, this effect can be attributed to the circumstance that the crucial alternative is not excludable. In the grammatical theory of implicatures, exhaustification excludes alternatives to a proposition provided they do not include it, as that would lead to a contradiction (see (50) in Sect. 5.2). Relevant cases are discussed in Sects. 5.3.2 and 6.3.

We have seen that counterfactual inferences behave like bona fide implicatures with respect to four criteria. As we see below, though, one property, concerning the alternatives behind these implicatures, sets them some way apart.

5.1.5 Alternativeness and scalarity

The grammatical theory of implicatures has mainly been used for computing scalar implicatures where alternatives are activated by scalar items; at propositional level, the relations between the items and their alternatives play out as logical inclusion. This is not an essential feature of the theory, however; implicatures based on non-logical scales or not on scales at all can be derived by the same method.

So can counterfactual inferences under the account proposed here, where the X item activates one alternative: the function that maps any propositional operation, any modal’s meaning, that is, to the identity function on propositions, the meaning, we might say, of the null modal. The relation holding between this alternative and the meaning of X, the identity function on modals’ meanings, does not make for a difference in logical strength at a propositional level. It comes down to the relation between the proposition that some proposition ϕ is, say, a possibility, and ϕ itself; the latter is not in general stronger or weaker than the former.

It is illustrative to compare (36), which involves a scalar item, with (37), which features X: while the proposition expressed in (36), that many of them are poultry, is weaker than the alternative proposition that all of them are poultry, the proposition expressed in (37), that the perpetrator ought to have known, is neither weaker nor stronger than the alternative proposition that he did know. The general rule is, after all, that counterfactual inferences and the sentences they are drawn from are logically independent of each other.

This distinguishes the proposal made here from the otherwise similar proposal made by Romoli (2015) to account for so-called soft presuppositions (Abusch 2010) in terms of implicatures. Soft presupposition triggers are assumed to be associated with alternatives, and the alternative ascribed to a factive verb like know is λϕλx ϕ, the ‘null’ propositional attitude, as one might call it. Here, a parallel can be seen to the assumption that the alternative to an X marked modal is λϕ ϕ, the ‘null’ modal. But also a contrast, insofar as they know that ϕ is arguably logically stronger than ϕ, while it is necessary that ϕ is not in the general case stronger or weaker than ϕ.

Thus the notion of alternativeness in play here is not in a logical sense a scalar notion. Technically, it has no need to be, as long as alternatives can be encoded in a morpheme like X. But substantially, too, it is a reasonable notion inasmuch as, in the words of Repp and Spalek (2021), we “juxtapose different worlds”:

In a counterfactual, the alternativeness is intuitively …prominent because the actual world (usually) is assumed to be false and the non-factual worlds are the worlds ‘of interest.’

In fact, a case could be made for a non-logical scale where the null modal, in effect the actual world, ranks higher than a full modal, a quantifier over possible worlds, making what is actually the case conceptually stronger than what could or should have been the case. I revisit this issue in Sect. 7.3.

In any case, we should note that modals have their own scalar alternatives, in that possibility modals are essentially existential quantifiers over worlds, whereas necessity modals are essentially universal quantifiers over worlds. This gives rise to implicatures which can coexist with those stemming from X, as (38) shows.

-

(38)

The first half of this German sentence occasions two implicatures. One is based on the possibility modal möglich and its scalar alternatives and says that the prejacent was no more than possible; in particular, it was not necessary.Footnote 12 The other is based on the subjunctive mood and says that the prejacent was not actualized.

The exact way in which it comes about will be specified presently.

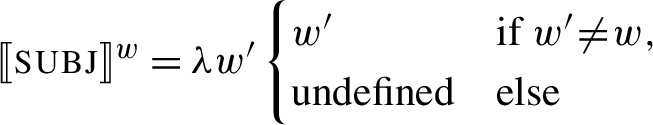

5.2 Definitions and a case study

Taking a cue from von Fintel and Iatridou (2023), I represent the counterfactual mood across the four languages under consideration by an uppercase X, neutrally as to whether it is articulated with mood or tense morphology, or with both.

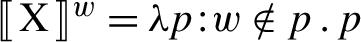

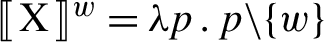

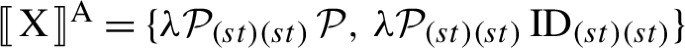

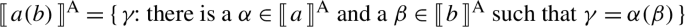

In the framework of alternatives and exhaustification developed and advanced by Chierchia (2006), Fox (2007), Chierchia et al. (2012), Chierchia (2013) and others, meanings have two separate dimensions: the ordinary semantic value (or OSV, 〚 ⋅ 〛) and the alternative semantic value (or ASV, \([\!\![\, \cdot \, ]\!\!]^{\mathrm{A}}\)), a set of alternatives to the former.

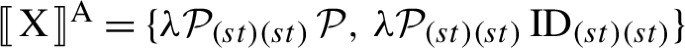

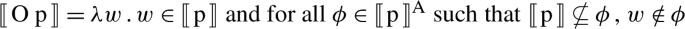

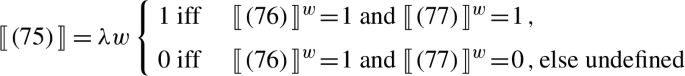

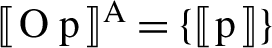

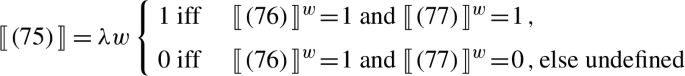

To start with, here are the definitions of the two semantic values of X:Footnote 13

-

(39)

-

(40)

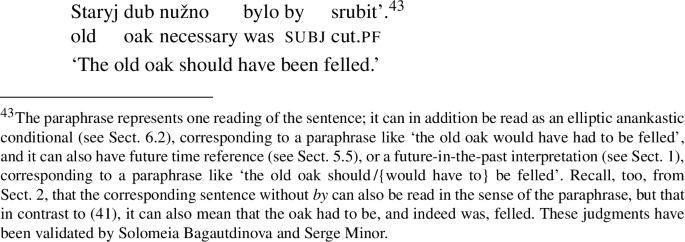

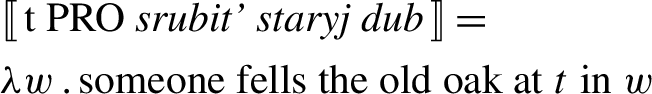

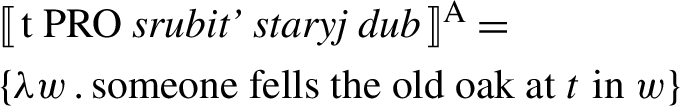

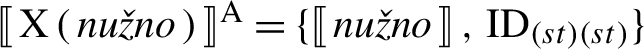

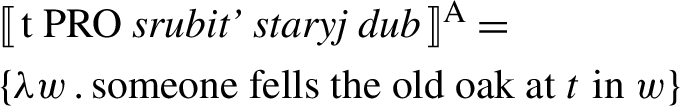

The ASV contains the OSV and the mapping from any operation over propositions to the identity operation. Let us focus on a simple Russian sentence, (41):

-

(41)

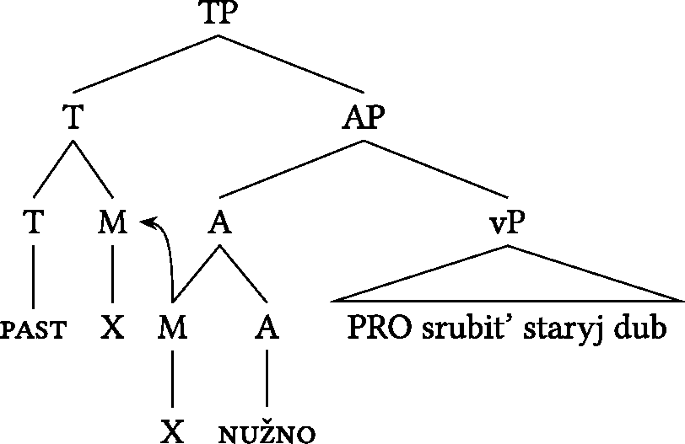

There is a counterfactual inference here: the old oak has not been, or was not, felled. Let us now build the meaning of the sentence in accordance with the rudimentary Logical Form in (42) to see how this entailment is derived.

O is the name of the covert exhaustification operator attaching at clausal level, and its sister’s two daughters are,

-

on the one hand, the join of the necessity modal nužno and the mood X,

-

and on the other, the prejacent infinitival clause:

-

(42)

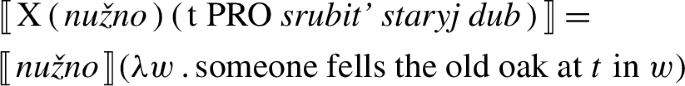

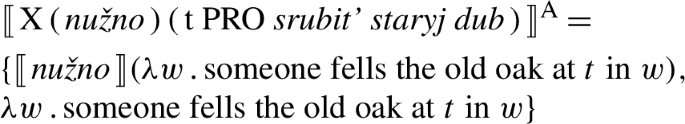

First, since the ordinary semantic value of the mood X is the identity function over propositional operations, the ordinary semantic value of the merge of the mood and its argument nužno ‘necessary’ equals this argument:

-

(43)

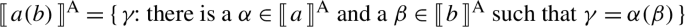

Second, to calculate the alternative semantic value (ASV) of that merge, we need the rule of Pointwise Function Application (Chierchia 2013, p. 138):

-

(44)

Using this, since the ASV of nužno itself is just the singleton set containing its OSV, there being no distinct alternatives, we obtain (45):

-

(45)

Let us now say that the ordinary and alternative semantic values of the infinitival complement of X ( nužno ), with an indefinite PRO subject and—for simplicity—a free variable t referring to a contextually given past time t, are the proposition in (46) and the singleton set containing that proposition in (47).Footnote 14

-

(46)

-

(47)

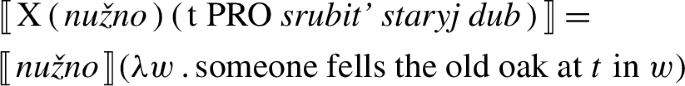

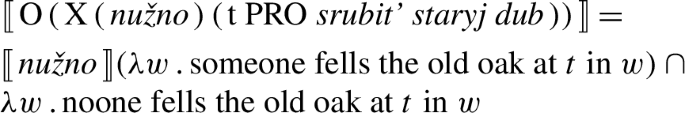

The next to last move in the composition of the meaning of (41) is the interpretation of the merge of X ( nužno ) and its argument, given in (48)—the OSV, a proposition—and (49)—the ASV, a set of two propositions.

-

(48)

-

(49)

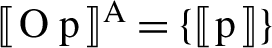

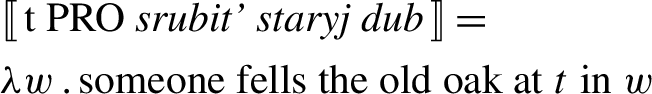

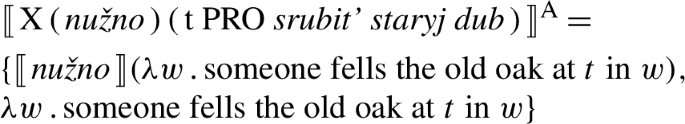

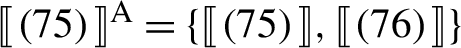

In a last step before the sentence meaning is finished, the activated alternatives in (49) will have to be factored into meaning through exhaustification; more exactly, it will be necessary for an exhaustification operator (called Exh or O, for ‘only’) to exhaustify the meaning in (48) with respect to the alternatives. The exhaustification amounts to adding a condition to (48) saying that its distinct alternative is not true. The definitions of the contribution of the exhaustifier O to OSVs and to ASVs (alternatives are reset once they are factored into OSVs through O) given in (50) and (51) are based on Chierchia (2013, p. 138), but the notation is adapted.

-

(50)

-

(51)

Now we can compute the final OSV of (41). Since exactly one of the two alternatives ϕ in \([\!\![\, \text{p} \, ]\!\!]^{\mathrm{A}} = \) (49) fails to include 〚 p 〛= (48), namely, the proposition that someone did fell the old oak, this proposition is subtracted from—or, put differently, its complement is intersected with—〚 p 〛= (48), resulting in (52):

-

(52)

In other words, the counterfactual inference that no one felled the old oak is now an entailment, an integrated truth condition.

In due course, we will see how this entailment becomes a factuality entailment when a negation comes between the exhaustifier and the mood (Sect. 5.3.2), and how it is blocked when it would conflict with the original ordinary semantic value or with an additive presupposition (Sects. 5.3.2 and 6.3). I also discuss how it is weakened or fails to come about under uncertainty (Sect. 5.5).

5.3 The two problem cases

The two phenomena which cause particular difficulties for existing approaches, as set out in Sect. 3, are straightforwardly accounted for by the given analysis.

5.3.1 The mood sits right

The circumstance that the mood can be marked in a matrix while the non-actuality entailment concerns a subordinate clause does not present a problem because the mood is not a ‘spinal’ category and does not apply to a proposition; it applies to a modal and triggers a counterfactual implicature concerning the modal’s argument, which can perfectly well be expressed in a subordinate CP.

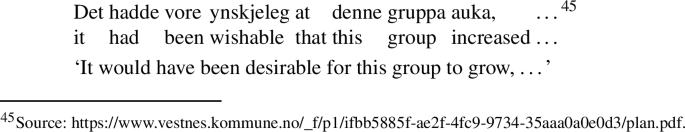

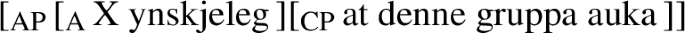

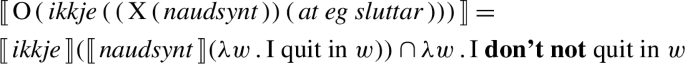

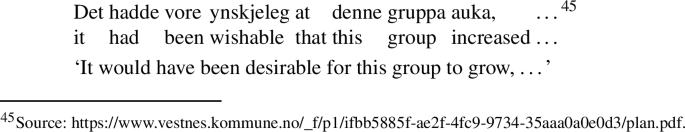

As indeed it is in the Norwegian example (53), with the LF sketched in (54): the mood modifies the modal ynskjeleg and the result takes a ‘that’ clause complement.

-

(53)

-

(54)

It may be noted that there is a fake past marking in the subordinate clause as well, though not a past perfect marking as in the matrix clause; like the X marking in ‘if’ clauses, this can be viewed as an uninterpretable concord marking (see Sect. 6.1).

5.3.2 Exhaustification over negation

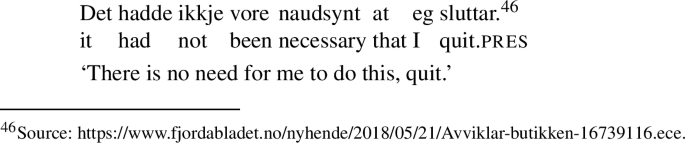

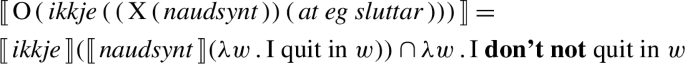

Like the sentences (21)–(24) discussed in Sect. 3.2, the Norwegian sentence (55) licenses a factuality inference for the complement clause: ‘I quit.’

-

(55)

This is immediately predicted by the present analysis on the reasonable assumption that the negation merges right above the mood-modified modal but right below O; once it has, the distinct alternative is not the modal’s prejacent but its negation, and in this way, the negative inference that would otherwise be there turns positive:

-

(56)

Note that this result persists if the standard assertional exhaustifier O is exchanged for the presuppositional exhaustifier proposed by Del Pinal (2021) and Bassi et al. (2021), as this exhaustifier will also scope over the negation in the cases in question, hence the fact that the implicature, qua presupposition, can project past a negation will not make a difference.

On the other hand, as noted in Sect. 3.2, X fails to license factuality inferences under negation when it attaches to possibility modals with empty ordering sources, and we can now see why: the definition of the ordinary semantic value of O in (50) restricts the exclusion of alternatives ϕ to propositions that do not include 〚 p 〛, and when 〚 p 〛 is that in view of the circumstances, something is not possible, ϕ will be that this something is not the case, which indeed includes 〚 p 〛, consequently, ϕ is not excluded, and X has no effect.

And in fact, there is hardly any detectable difference in meaning between (57-a), with past perfect subjunctive, and its past indicative counterpart (57-b).

-

(57)

5.4 A note on the syntax of the mood

Recall from Sect. 2.1.1 that the counterfactual mood is marked in various ways across Czech, Russian, German and Norwegian, often with a combination of mood (subjunctive) and tense (past or pluperfect) marking, where mood marking may be verbal inflection or a particle or clitic, and sometimes with tense marking alone. This morphological realization must somehow be enabled in the syntax, and while there are several ways to go about it (see, e.g., Harizanov and Gribanova 2019 for a discussion of the general issues), I adopt a simple version of head movement, where X merges internally into T.

(58) supplies an illustration of the syntax of the Russian paradigm example (41), elaborating on the rudimentary structure in (42) but omitting the insertion of O.Footnote 15

-

(41)

-

(58)

Here, the mood (M) feature X adjoins to T, and as a result, the material dominated by T—the temporal feature past and X—can spell out as bylo and by, i.e., the past (neuter) form of the copula and the subjunctive particle, at Phonetic Form.Footnote 16 As far as Logical Form is concerned, however, this adjunction operation is vacuous.

A consequence of this view is that the past tense form as such is ‘polysemous’; with by, it is temporally neutral and just as much an exponent of pres as of past.

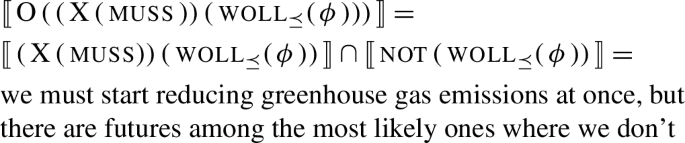

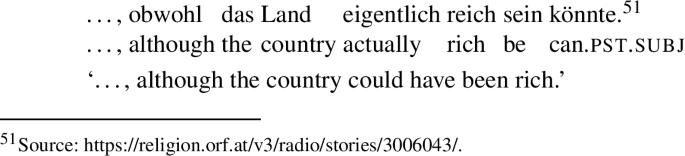

The German case (59) is a bit different insofar as the mood comes to expression in an umlaut, past tense form of a verb, the modal auxiliary können ‘can’, ‘may’:

-

(59)

The form könnte thus spells out no less than three elements:

-

the mood (X),

-

the tense (pres), and

-

the finite modal auxiliary verb’s root (konn).

(60) may illustrate a complex V dominating konn; X adjoins to T hosting pres, enabling a spellout as the word form könnte (note the right-branching structure).

-

(60)

.

In Czech and Norwegian, the T material will regularly have a complex articulation, in Czech in the form of a subjunctive backward-shifting auxiliary and a participle, in Norwegian in the form of a backward-shifting auxiliary and a past participle or a past tense modal auxiliary and a perfect infinitive. These complex past / past perfect forms are not per se temporal morphemes; rather, the pluperfect in Norwegian, say, either expones a plain past-under-past or a time-neutral (pres / past) X.

5.5 The robustness of the counterfactual implicature

Alternative-based implicatures are more or less strongly communicated, or robust. In principle, particularly if the alternatives are not at-issue, they can be ‘canceled’, ‘suppressed’ or ‘suspended’— in terms of the grammatical theory, the exhaustifier O can be missing, or alternatives can remain inactive (Chierchia et al. 2012, p. 2317).

5.5.1 The active alternative and the opinionated speaker

With regard to the counterfactual inference as an implicature, the picture is mixed. On the one hand, it seems relatively robust, at least as far as active alternatives are concerned. It is a rare situation where the truth value of the prejacent of a modal is not somehow under consideration, along with that of the modality. This is maybe understandable given that the alternative is introduced by a morpheme which has no other job, and which always has a competitor in its own absence.

Moreover, it has recently been suggested (see, e.g., Gotzner and Romoli 2022) that implicatures are less robust when they require lexical substitutions than when they are constituents which are ‘already there’ in the sentence. And the alternative to the X marked modalized sentence is indeed ‘already there’ as a constituent in the sentence and does not have to be retrieved from the lexicon.

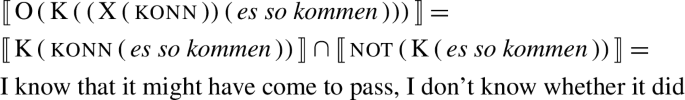

On the other hand, as noted in Sect. 5.1.2, the counterfactual inference relies on opinionatedness in the same way as scalar implicatures do: it will not be drawn unless the speaker can be taken to have an opinion on the truth of the alternatives. While Chierchia et al. (2012, p. 2317) suggest, concerning scalar implicatures, that this factor enters into a choice between representations containing or not containing O, the exhaustification operator, Meyer (2013, p. 113) proposes that it corresponds to the relative scope between O and the covert doxastic operator K, where K > O gives us the scalar implicature but O > K just gives us the weak implicature that the speaker does not know the alternative to be true.

Whichever way one chooses to model the dependence of scalar implicatures on the well-informed speaker, it will extend to counterfactual implicatures. Let us, for concreteness, review (35) from Sect. 5.1.2 through the lens of Meyer’s theory:

-

(35)

The context motivates that the LF with K under O is the one to be chosen, with the interpretation defined here (where past temporal reference is abstracted away):

-

(61)

5.5.2 Counterfactuality and future

As noted in Sect. 2.2, the counterfactuality of the counterfactual inference, which is generally strong in cases with past or present time reference, is weaker and less categorical when future events are referenced. Dobrušina (2016, pp. 35, 13) thus writes: “In the strict sense of the word, in the case of reference to the future, one can only speak of a low probability that the situation occurs and not of counterfactuality.” Footnote 17 In the same spirit, Fabricius-Hansen et al. (2018, p. 56) note: “When the modal …refers to the present, the subjunctive has a lesser effect than when it refers to the past.” Footnote 18

It is tempting to try to subsume this effect under the opinionatedness criterion. The idea would be that speakers will tend to be less confident about eventualities that are in the future than about eventualities that are in the past or the present.

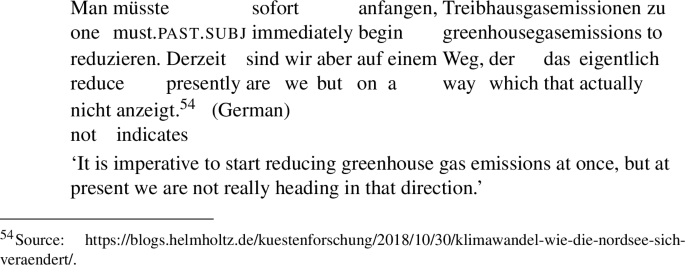

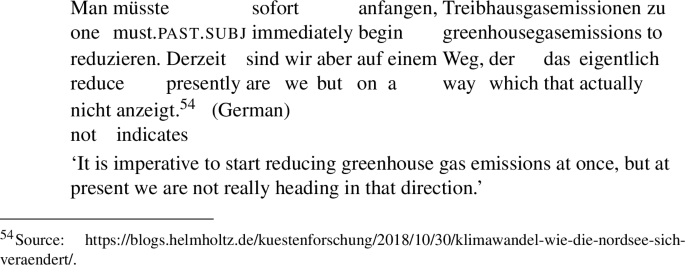

Let us first take a close look at a case in point:

-

(62)

The continuation to the modalized, mood marked sentence makes two points clear:

-

It cannot be excluded that greenhouse gas emission reductions begin immediately, that is, some continuation of the actual world is contained in the prejacent.

-

However, we are not on course for that—in other words, those continuations are not among those where events take their natural course, the ‘inertia worlds’—see Dowty (1979, p. 148) for a locus classicus of this notion.

Generalizing, it would seem that when the modalized sentence refers to the future, the counterfactual inference plays out as the negation of the prejacent relatively to the inertia worlds, the continuations where events take their natural course.

This could be modeled in terms of quantification over possible continuations in branching time (see for overviews, e.g., Stojanovič 2014; Cariani and Santorio 2018). One might say that generally, claims about what will be the case at a certain future time are not made indiscriminately for all possible branches, but more selectively, for the most likely ones (Kaufmann 2005) or the most normal ones (Copley 2009).

Following this line, the excludable alternative to the first half of (62) might not be that we start reducing emissions immediately but rather, roughly phrased, that we are on course for it, and the implicature would be that we are not on course for it, so it is possible but not probable. The difference could be encoded in an operator saying that its prejacent comes true in ‘expectable continuations’ (Krifka 2011).

There is a parallel here to the covert operator introduced by Meyer (2013), K, to model a difference between weak and strong scalar implicatures (see Sect. 5.5.1); a K scoping below the exhaustification operator O gives us the former. By the same token, a modal future operator like the one conjectured here would systematically scope below O and give rise to an implicature between the two extremes regarding strength, ignorance and counterfactuality: the prejacent is unlikely to come true.

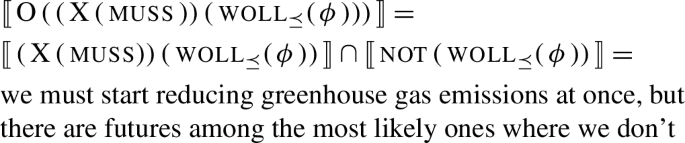

For concreteness, let us consider how (62) would be structured and interpreted in terms of O, the modal muss, and the operator woll⪯ from Kaufmann (2005, p. 256) (where ϕ abbreviates man Treibhausgasemissionen zu reduzieren sofort anfangen):

-

(63)

The parallel between K and woll⪯ is not perfect, but there is a significant common core, as in (61) and (63) alike, the effect of exhaustification is, as it were, cushioned by an operator with a universal force between the negation and the bare prejacent, between not and ϕ in (63). The upshot is that the attitude that is expressed to the truth value of this proposition is not plain disbelief but uncertainty or doubt.

Sketchy as these remarks are, I hope they lend some substance to the idea that the relatively weak counterfactuality inference in non-opinionatedness contexts on the one hand and in future contexts on the other are parts of the same picture.

5.6 The site of exhaustification

Most of the examples that have been considered have been simple sentences, or in any case, the exhaustification operator has been assumed to attach at the top level. That is hardly the only level for O to attach at, however. In addition, intermediate clausal levels and non-clausal type t levels both seem to be of potential relevance.

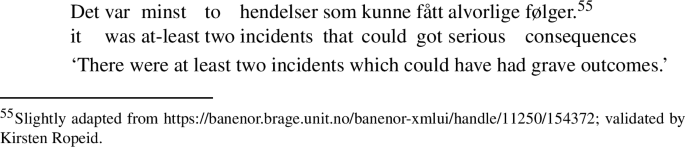

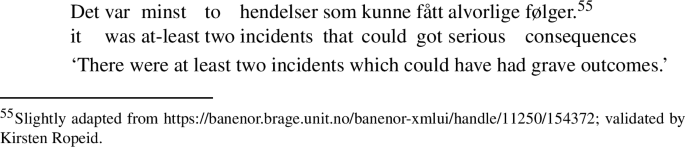

As an example of the former possibility, consider the Norwegian sentence (64). Here, the counterfactual implicature cannot plausibly be computed globally; rather, exhaustification must be assumed to take place in the relative clause:

-

(64)

The context states that there were six fatalities on railways in Norway in 2001. The counterfactual implicature would contradict this if it were computed at root level, as it would be that there were one or zero incidents with grave outcomes. What is evidently meant by (64) is that there were at least two incidents that could have had but didn’t have grave outcomes, a reading resulting from a local O insertion.Footnote 19

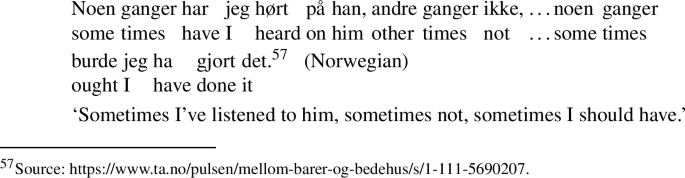

In fact, a clausal boundary is not essential for a scope-bearing element to scope over O on the most accessible reading of a sentence. (65) is a case in point:

-

(65)

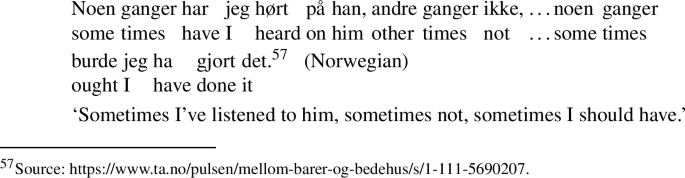

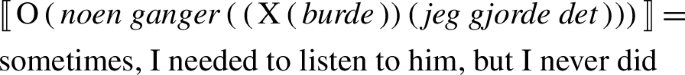

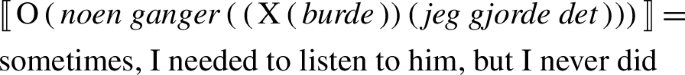

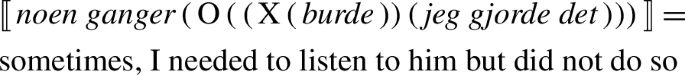

While in (64) there was a possibility modal with a metaphysical modal base and an empty ordering source, (65) contains a necessity modal with a teleological ordering source. The common denominator is that O insertion at root level will result in an implicature contradicting the context—in (65), that I’ve never listened to him:

-

(66)

The natural site for O to attach is just below the adverbial noen ganger ‘sometimes’, resulting in the reading that sometimes, I needed to listen to him but didn’t:

-

(67)

To be sure, there is more to be found out about under what conditions O can or must attach at what type t levels as far as alternatives induced by X are concerned, but it is safe to say that the flexibility which is afforded by the grammatical theory in this regard (see, e.g., Chierchia et al. 2012, p. 2318) is welcome.

6 Counterfactual conditionals

The counterfactual mood has been defined as an operator that operates on modals (see Sect. 5.2, in particular (39)). The notion of a modal is general: any expression with a denotation of type (st)t or, in the composition scheme adopted in Sect. 5.2 (see footnote 42), a meaning of type (st)(st), mapping a proposition to a truth value or to another proposition.

Such an expression may now be silent, more accurately, it may be that all that’s audible of it is an ‘if’ clause; then the ‘modal’ is, following Kratzer, a silent necessity operator whose modal base is restricted by that clause or, following Lewis, a binary conditional operator halfway saturated.

In any case, the upshot is a conditional, and if a counterfactual mood is present, it applies to the unary propositional operator, which in turn inputs the consequent. In consequence, this consequent will standardly be implicated to be counterfactual, while in principle, nothing will be implicated for the antecedent. However, jointly, the counterfactual implicature for the consequent and the whole conditional will—by modus tollens—entail that the antecedent is also counterfactual. It can happen, though, that a counterfactual implicature fails to get off the ground to begin with; this is the situation with ‘semifactuals’, where the alternative is ‘non-excludable’.

These and further issues are treated in more detail in the following sections.

6.1 A standard case

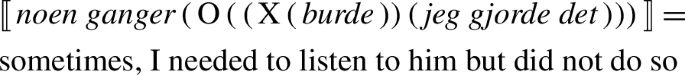

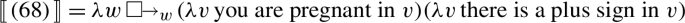

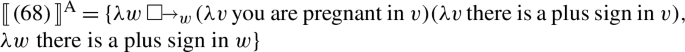

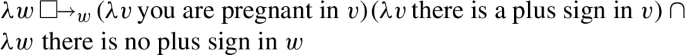

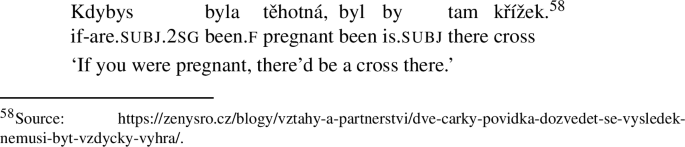

Consider the Czech sentence (68):

-

(68)

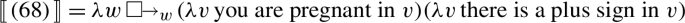

It can be assigned a fragmentary LF like (69), where the matrix TP level is omitted, broadly following Lewis (1973):

-

(69)

.

Note that the conditional operator  combines with X only after it has combined with the kdy ‘if’ clause, becoming a unary modal and a matching argument for X.

combines with X only after it has combined with the kdy ‘if’ clause, becoming a unary modal and a matching argument for X.

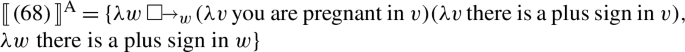

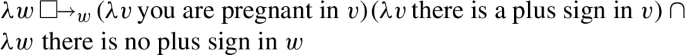

6.1.1 Consequent and antecedent

The ordinary semantic value (OSV) and the alternative semantic value (ASV) of (68) will be as outlined in (70) and (71):

-

(70)

-

(71)

When these are fed to the exhaustifier O, the ordinary semantic value becomes (72), where the second line is the counterfactual implicature:

-

(72)

In other words, the counterfactual mood effects the counterfactual implicature that there is in fact no plus sign to be seen on the pregnancy test. And by modus tollens, which is valid on every standard possible world analysis of conditionals, it follows that you are also not pregnant (see, though, Yalcin 2012 for a critical discussion).

That the counterfactuality of the antecedent is only indirectly predicted accords well with an argument put forth by Stalnaker (1975) against a presupposition that the antecedent is contrary to fact:

Consider the argument, The murderer used an ice-pick. But if the butler had done it, he wouldn’t have used an ice-pick. So the murderer must have been someone else. The subjunctive conditional premiss in this modus tollens argument cannot be counterfactual since if it were the speaker would be blatantly begging the question by presupposing, in giving his argument, that his conclusion was true.

While any theory where antecedent falsity is presupposed is indeed challenged by this argument, the hypothesis that antecedent falsity follows from the implicature of consequent falsity and the truth of the conditional as a whole is, on the contrary, strengthened by it, as the argument simply spells out that same sequitur.

6.1.2 Interpretable and uninterpretable X marking

Note that the X marking in the ‘if’ clause is not in a position to be interpretable, as there is no modal anywhere there. But thanks to the modus tollens effect just noted, it does not need to be interpreted, because the antecedent inherits, so to speak, the counterfactual inference from the consequent. Instead, the marking can, and must, be treated as a reflex of that in the consequent clause, as a case of ‘mood concord’.

More specifically, the interpretable (i ) - uninterpretable (u ) concord relationship between matrix and ‘if’ clause mood marking has an illustration in (73). The u X marking (-by-) inside the kdy- ‘if’ CP is c-commanded by the i X marking by- outside it and can therefore be ignored semantically.

-

(73)

.

6.2 Elliptical counterfactuals

A further argument in support of the proposal comes from sentences like (7), (8), (9) and (10), repeated here for convenience:

-

(7)

-

(8)

-

(9)

-

(10)

The only way to read these sentences is as concealed, or elliptical, counterfactuals, and this fact has a straightforward explanation under the proposed analysis.

Note that there is no modal of any kind in these sentences—no overt modal at any rate. However, the mood presupposes a modal of some kind because it needs one to apply to; hence, one must assume the covert presence of one. And the only kind of modal that can be covert, according to Kratzer (1978) and much later work, is the necessity modal that figures as the default operator in conditionals, where it is restricted by the antecedent—which in (7)–(10) is a zero pronoun. In this manner, the mood sets off a chain of interpretive moves ending in a complete counterfactual conditional construction—semantically if not syntactically.

Sometimes, though, an elliptical counterfactual is an overtly modalized clause. The Russian sentence (74) is a case in point.

-

(74)

It can then be difficult to tell whether the overt modal belongs to the consequent or is the modal that serves as conditional operator—in the terminology of von Fintel and Iatridou (2023), whether an ‘exo-X’ or an ‘endo-X’ reading obtains. On the one hand, the former case will surely occur, as there is no reason or means to exclude necessity modals from appearing in conditionals’ consequents. On the other hand, in an ‘anankastic’ sentence like (74), expressing a necessary condition (Sæbø 2020), it seems that the modal, nužno, is not affected by the counterfactual inference but rather is the modal the mood modifies, whether there is a covert modal on top of it (as argued by Condoravdi and Lauer 2016) or not.

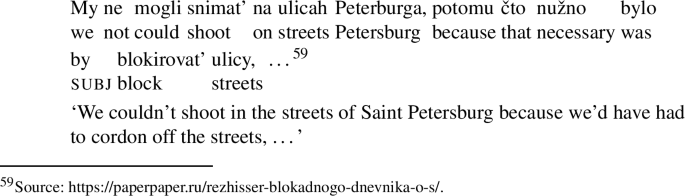

6.3 Semifactuals and Anderson cases

It has often been noted that consequents can stay untouched by any counterfactual inference from conditionals. This is particularly so with semifactuals, which contain a focus particle ‘even’ or an additive adverb ‘still’ associating with the ‘if’ clause, or more precisely, with the conditional operator including the ‘if’ clause, and triggering the presupposition of the same sentence under the substitution of the alternative—effectively, the actual world—for the associate.

The upshot is a factual presupposition for the consequent. That this blocks any counterfactual implicature originating in an X marking falls out naturally from the proposed analysis, once the definition of the exhaustification operator is modified to accommodate presuppositions. The key point is that the alternative whose exclusion is key to the counterfactual implicature turns out not to be excludable. Consider:

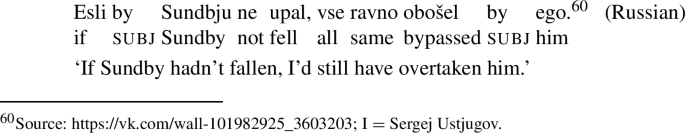

-

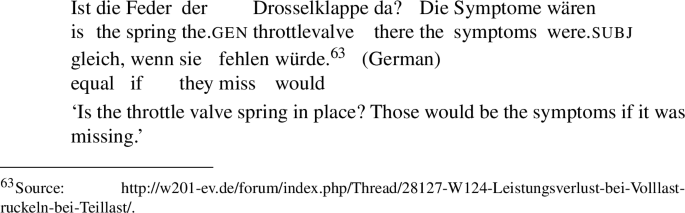

(75)

In (75), the additive adverbial vse ravno introduces the presupposition that Ustjugov overtook Sundby in the salient alternative to the relevant accessible worlds where Sundby didn’t fall. Let us say that this alternative is the world of evaluation, where Sundby did fall; (75) is thus only true or false if Ustjugov did overtake Sundby.

-

(76)

-

(77)

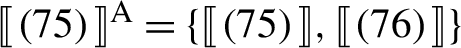

The OSV of (75) is thus as defined in (78), and its ASV is as defined in (79):

-

(78)

-

(79)

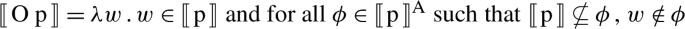

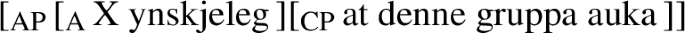

To see that the factual presupposition (76) overrides any counterfactual implicature for the same proposition, (50) must be replaced by a definition of the exhaustifier O where its argument is a partial  function and excludable alternatives are characterized in terms of sets of worlds where ϕ and p are true—(80):Footnote 20

function and excludable alternatives are characterized in terms of sets of worlds where ϕ and p are true—(80):Footnote 20

-

(80)

. \([\!\![\text{O p}]\!\!]^{w} = \begin{cases} 1 \text{ iff } & [\!\![\, \text{p} \, ]\!\!]^{w} \! = \! 1\text{ and }\phi ^{w} \! = 0\text{ for all } \phi \in [\!\![\, \text{p} \, ]\!\!]^{\mathrm{A}} \text{ such that} \\ & \lambda w^{\prime} [\!\![\, \text{p} \, ]\!\!]^{w^{\prime}} \! \! = \! 1 \nsubseteq \lambda w^{\prime \prime} \phi ^{w^{\prime \prime}} \! \! = \! 1 \, , \\ 0 \text{ iff } & [\!\![\, \text{p} \, ]\!\!]^{w} \! = 0\text{ and }\phi ^{w} \! = \! 1\text{ or }0 \text{ for all such }\phi \, , \text{or }\\ & [\!\![\, \text{p} \, ]\!\!]^{w} \! = 1\text{ and }\phi ^{w} \! = \! 1 \text{ or }0\text{ for all and 1 for some such }\phi \end{cases}\)

When O applies to (75), there will be no excludable alternatives, i.e., no \(\phi \in [\!\![\, \text{(75)} \, ]\!\!]^{\mathrm{A}} \) s.t. \(\lambda w^{\prime} [\!\![\, \text{(75)} \, ]\!\!]^{w^{ \prime}} \! \! = \! 1 \nsubseteq \lambda w^{\prime \prime} \phi ^{w^{ \prime \prime}} \! \! = \! 1 \), hence no counterfactual implicature will surface. For the only distinct alternative ϕ is (76), which must be true for p = (75) to be true, consequently, the worlds where ϕ is true will include the worlds where (75) is true, leaving O inert. Concretely, for p = (75), (80) reduces to (81), because two conjuncts are trivially true and one disjunct is trivially false:

-

(81)

. \([\!\![\,\text{O (75)} \,]\!\!]^{w} = \begin{cases} \ 1 \text{ iff } & [\!\![\, \text{(75)} \, ]\!\!]^{w} \! = \! 1 \, , \vspace{.1cm} \\ \ 0 \text{ iff } & [\!\![\, \text{(75)} \, ]\!\!]^{w} \! = 0 \end{cases}\)

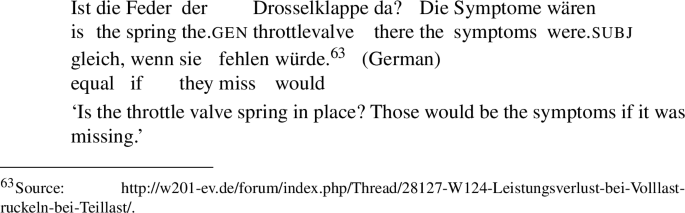

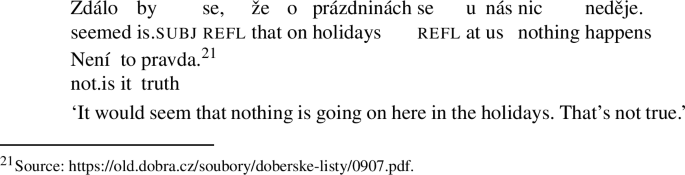

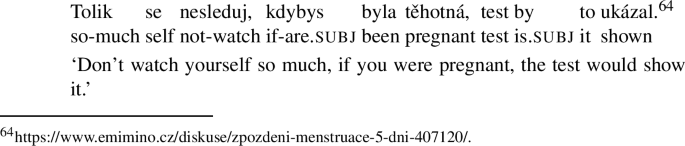

This reasoning carries over to cases where the consequent is evidently true, in the absence of additive particles or adverbials, including so-called ‘arsenic cases’ or ‘Anderson cases’, with reference to Anderson (1951): subjunctive conditionals used in support of the truth of the antecedent. Authentic examples are not easy to find, but (82) is one.Footnote 21

-

(82)

As in the examples constructed by Anderson, the consequent is an priori truth—a proposition true in every world of utterance: the symptoms of some engine are the same as they are in the world of utterance. As a subjunctive-activated alternative to the conditional, that proposition includes any set of worlds, hence the proviso built into (80)—\(\lambda w^{\prime} [\!\![\, \text{p} \, ]\!\!]^{w^{\prime}} \! \! = \! 1 \nsubseteq \lambda w^{\prime \prime} \phi ^{w^{\prime \prime}} \! \! = \! 1 \)—cannot be satisfied. Consequently, nothing about the truth or falsity of the consequent or antecedent can be concluded.

In connection with semifactuals, on the other hand, the antecedent is evidently always understood to be false. In the light of the theory at hand, this has nothing to do with mood, but everything to do with the presupposition, triggered by an overt or covert additive particle or adverb, that the consequent is true in the salient alternative to the closest possible worlds where the antecedent is true. Two assumptions ensure that the antecedent is presupposed to be false. One has already been made: the salient alternative to the worlds where the antecedent is true that are closest to the actual world is this same world. The second is that this world and those worlds are distinct; it follows that the actual world is not among the closest worlds where the antecedent is true, in other words, the antecedent is false in the actual world.

6.4 Argument conditionals

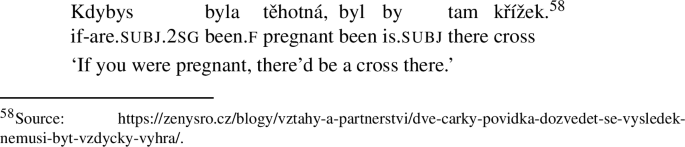

Conditionals whose consequents presuppose their antecedents, discussed by, among others, Fabricius-Hansen (1980), Onea (2015) and Schwabe (2016), are a challenge to the proposed analysis. Sentences like (83) are cases in point.

-

(83)

They are challenging because the predicted counterfactual implicature, denying the consequent, would seem to presuppose the antecedent; in the case at hand:

-

Antecedent: that you are pregnant

-

Consequent: that the test shows that you are pregnant

-

Counterfactual implicature: that the test does not show that you are pregnant

And that would conflict with the inference that the antecedent is counterfactual—the hearer is not pregnant.

This tension can be resolved by leaning on the theory of presupposition set out by Schlenker (2008). Here, pq (q with p as a presupposition) is semantically equal to p&q (p and q without p as a presupposition). The pragmatics is different, though: to observe the maxim “Be Articulate!”, p&pq is chosen over pq unless p is transparent, i.e., unless it is redundant given the context set and the local context.

Now p is indeed transparent when it is presupposed in a conditional consequent and identical to the antecedent. In this local context, therefore, pq is equal to p&q pragmatically and semantically, and (83) is equivalent with

-

(84)

. if you were pregnant, you’d be pregnant and the test would indicate it

where the presuppositional verb show is replaced by the non-presuppositional verb ‘indicate’ (granting that this may not be a perfect minimal ±presuppositional pair).

This move shields cases like (83) from any inconsistency and explains how the antecedent is inferred to be false although the consequent appears to presuppose it. To see this point clearly, observe that (84) has the structure of (85-a).

-

(85)

The counterfactual implicature—the negation of the consequent—therefore has the structure of (85-b), hence jointly, these two premises sustain the conclusion (85-c), the negation of the antecedent, as before, by modus tollens.

7 Discussion and conclusions

Sections 5 and 6 provide answers to many questions, but some have been left open, and some of the answers spur new questions. The present, final section addresses a few of these loose ends, suggesting ways to tie them up.

Others will have to remain loose for the time being. These are briefly reviewed towards the end of the section. Here a summary is also given of the questions that have been discussed and the answers that have been proposed.

7.1 A challenge: missing modals

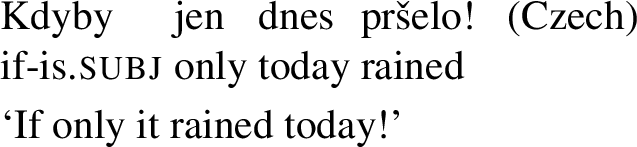

As defined, the X mood requires a modal, even if the modal is only covertly present, as so often in conditionals, elliptical or not. But there are a couple of constructions which are usually X-marked yet lack an overt modal and where it is not clear how to posit a covert one. One is the free-standing ‘if’ clause in the role of an optative, another is the equative, or similative, ‘as if’ construction.

7.1.1 Insubordinate conditional clauses

Insubordinate conditional clauses used as optatives are standardly X-marked. (86) is one of the examples cited by Grosz (2012):

-

(86)

Grosz (2012) argues against a description of these clauses as elliptical conditionals where the matrix is elided, and for an analysis with an exclamation operator which maps a proposition to an expressive meaning. It is difficult to see how to reconcile this theory with the theory of counterfactual mood that I have argued for.

The alternative is to assume the structure to include, after all, a covert necessity modal restricted by the ‘if’ clause, and a null pronominal consequent proposition. This is the line taken by Bech (1951), who considered a ‘latent’ consequent clause to be generally present with Czech insubordinate kdyby clauses:

Sometimes the kdyby clause is not connected with any superordinate clause. Then it must be decided what to interpolate according to the context.Footnote 22

For Bech, the optative flavor is a secondary effect which may or may not occur.

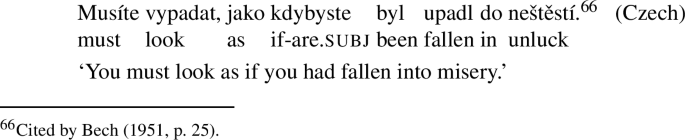

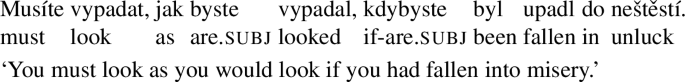

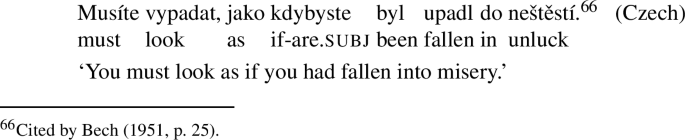

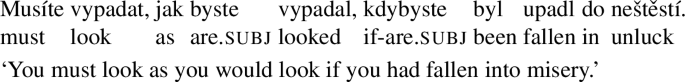

7.1.2 ‘As if’ clauses

Another class of X-marked ‘if’ clauses which appear not to be parts of conditionals are those that form adverbials with an equative particle: German als, Russian kak, Norwegian som, Czech jako, as in (87).

-

(87)

Again, recent work argues against positing a conditional modal for the ‘if’ clause to restrict or halfway saturate: Bledin and Srinivas (2019) describe English as if as an atomic complementizer whose mother CP adjoins to VP. And again, that argument has to be countered for the X-marking to be accounted for along the present lines. While that would lead us too far, it is interesting to note that here, too, Bech (1951, p. 25) assumes a ‘latent’ conditional consequent, so that (87) is equivalent with (88):

-

(88)

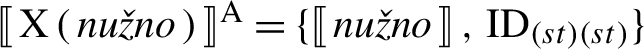

7.2 Propositional attitudes, a composition challenge

It has been assumed that the mood needs to compose with something of the logical type of a modal. This assumption faces a problem when what the modal evidently composes with does denote a function from propositions, only not to propositions or truth values but to functions from individuals (to propositions or truth values).

Thus the mood can, by all accounts, attach to a propositional attitude predicate. (16) in Sect. 2.2 was one case in point, and (89) is another.

-

(89)

The counterfactual inference concerns the control infinitive complement of wollen. This would follow if the mood could apply to the attitude verb after this verb has applied to the individual subject argument but before it applies to the proposition, but that runs counter to any conventional semantics for propositional attitudes.

There are three possible solutions to this dilemma:

-

(1)

Define another variant of 〚 X 〛, one that inputs functions from propositions to functions from individuals to propositions instead of propositions, and a corresponding variant of \([\!\![\, \text{X} \, ]\!\!]^{\mathrm{A}}\):

\([\!\![\, \text{X} \, ]\!\!]^{\mathrm{A}} = \{ \lambda P_{(st)(e\/(st))} \, P \, , \, \lambda P_{(st)(e\/(st))} \, \lambda p \lambda x \, p \}\)

-

(2)

Introduce another composition principle, additionally to functional application, etc., to take care of the composition of X and a propositional attitude predicate:

\([\!\![\, \alpha _{((st)(st))((st)(st))} \, \beta _{(st)(e\/(st))} \, ]\!\!]= \lambda p_{st} \lambda x_{e} \, [\!\![\, \alpha \, ]\!\!]( \lambda q_{st} \, [\!\![\, \beta \, ]\!\!]( q ) ( x ) ) (p)\)

-

(3)

LF raise the complement clause and attach X below that but above the associated variable binder—as in the rudimentary LF for (89) in (90),

-

1)

. [ [ she [ kiss he ] ] [ X [ \(\mu _{i} \) [ she [ woll \(\phi _{i} \) ] ] ] ] ]

where μ abstracts over the variable left by the raised complement clause kiss(he)(she) and thus creates the appropriate logical type for X to apply to.

-

1)