Abstract

A growing share of mortgages display some financial assistance from sellers, or seller contributions, leading to an inflated transaction price thus distorting the loan-to-value ratio (LTV). Our study finds that such loans have sharply increased rates of delinquency, even after accounting for this LTV distortion effect. Further, when contributions are more likely to have been requested by the buyers, instead of the sellers bringing them to the bargaining table, the association with delinquency is clearest. These contributions signal buyers’ potential liquidity constraints which may make them more vulnerable to financial shocks after origination, thus more likely to enter delinquency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

Data used in this research paper is Fannie Mae proprietary information and is not publicly available.

Notes

It should be noted that such distinction may not be as straightforward, since borrowers can choose to pay more points to reduce interest rate or pick the smaller closing cost option through a slightly higher rate, while the lenders’ profit are likely not affected. This choice reflects borrowers’ liquidity constraints and their expected tenures in a property.

Per regulation policy, sellers are usually prohibited from giving the potential buyers downpayment funds, but they can provide some gift assistance in term of the closing cost, so long as it falls within the limits set by the lender.

In 2015 the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) combined relevant mortgage disclosure regulations into a single Closing Disclosure. Information from this form is captured in a new common industry dataset called the Uniform Closing Dataset.

The HUD-1 form was used to itemize the services and fees charged to the buyer and to the seller by the lender, prior to the introduction of CFPB’s Closing Disclosure in 2015.

See Sect. 3.7 for a comparison of the impact of seller contribution on loan performance based on the measures from these alternative data sources.

Maximum IPC amount for investor properties is 2%, regardless of LTV, for more details see: https://www.fanniemae.com/content/guide/selling/b3/4.1/02.html.

Note that the model includes FICO scores below 620. Although a borrower with a FICO score in this range would typically not be able to obtain a conforming loan in the current environment, these scores were more common in the pre-Great Recession years.

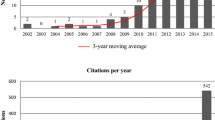

We present the full set of yearly coefficient estimates in Appendix (Table 9). We observe that for the 2006–2007 year pair, there is a more notable difference in the coefficient estimates across these two years than for any other year pair. That being said, for ease of exposition, the figures present results by year-pair samples.

These fees include those charged for: underwriting; appraisal; escrow; discount points; prepaid interest; mortgage insurance; rate lock; processing; credit report; loan origination; or loan application.

References

Asabere, P. K., & Hoffman, F. E. (1997). Discount point concessions and the value of homes with conventional versus nonconventional mortgage financing. The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 15(3), 261–270.

Beracha, E. (2009). Capitalization of seller-paid concessions near the recent peak of the housing bubble. Journal of Housing Research, 18(2), 143–150.

Bian, X., Lin, Z., & Liu, Y. (2018). Bargaining, mortgage financing, and housing prices. Journal of Real Estate Research, 40(3), 419–452.

Campbell, J. Y., & Cocco, J. F. (2015). A model of mortgage default. The Journal of Finance, 70(4), 1495–1554.

Campbell, T. S., & Dietrich, J. K. (1983). The determinants of default on insured conventional residential mortgage loans. The Journal of Finance, 38(5), 1569–1581.

Cotterman, R. F. 1992. Final Report: Seller Financing of Temporary Buydowns. US Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Ferreira, E. J., & Stacy Sirmans, G. (1989). Selling price, financing premiums, and days on the market. The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 2(3), 209–222.

Foote, C. L., Gerardi, K., & Willen, P. S. (2008). Negative equity and foreclosure: Theory and evidence. Journal of Urban Economics, 64(2), 234–245.

Hayunga, D. K. (2018). Sales concessions in the US housing market. The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 56(1), 33–75.

Johnson, K., Anderson, R., & Webb, J. (2000). The capitalization of seller paid concessions. Journal of Real Estate Research, 19(3), 287–300.

McFarlane, A. 2012. The Impact of Limiting Sellers Concessions to Closing Costs. Cityscape, pp.211–224.

Quercia, R. G., & Stegman, M. A. (1992). Residential mortgage default: A review of the literature. Journal of Housing Research, 3(2), 341.

Soyeh, K., Wiley, J., & Johnson, K. (2014). Do buyer incentives work for houses during a real estate downturn? The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 48(2), 380–396.

Von Furstenberg, G. M. (1969). Default risk on FHA-insured home mortgages as a function of the terms of financing: A quantitative analysis. The Journal of Finance, 24(3), 459–477.

Winkler, D. T., & Gordon, B. L. (2015). Seller-paid concessions from 2004 to 2012: Implications for house selling price and days on the market. Journal of Real Estate Research, 37(4), 537–562.

Woodward, S.E. 2008. A study of closing costs for FHA mortgages. US Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Michael LaCour-Little for valuable feedback on this paper. The authors are solely responsible for the contents, findings, and views expressed in this paper, which do not necessarily reflect the opinions of their respective employers. Any errors are our own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Carroll, F., Mota, N., Wu, W. et al. Seller Contributions and Mortgage Performance. J Real Estate Finan Econ (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-023-09968-7

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-023-09968-7