Abstract

There is a limited number of studies examining the influence of birth complications on the length of the subsequent interpregnancy interval (IPI). This study aimed to study the association between different pregnancy complications at first pregnancy and subsequent IPI. All women with their first and second pregnancies were gathered from the National Medical Birth Register for years 2004–2018. A logistic regression model was used to assess the association between the pregnancy complication (gestational hypertension, gestational diabetes (GDM), preterm birth, perinatal mortality, shoulder dystocia) in the first pregnancy and subsequent length of the IPI. IPIs with a length in the lower quartal were considered short IPIs, and length in the upper quartal as long IPIs. Adjusted odds ratios (aOR) with 95% CIs were compared between the groups. A total of 52,709 women with short IPI, 105,604 women with normal IPI, and 52,889 women with long IPI were included. Women with gestational hypertension had higher odds for long IPI (aOR 1.12, CI 1.06–1.19), GDM had higher odds for short IPI (aOR 1.09, CI 1.09–1.13), preterm delivery had higher odds for short and long IPI (aOR 1.12, CI 1.07–1.17 for both), and perinatal mortality had higher odds for short IPI (aOR 8.05, CI 6.97–9.32) and lower odds for long IPI (aOR 1.13, CI 0.93–1.38). Women with gestational hypertension and preterm birth had higher odds for long IPI, and women with diagnosed GDM and perinatal mortality had higher odds for short IPI. We found no evidence of a difference in the length of the IPI for women with shoulder dystocia. More research on the reasons behind the subsequent long and short IPI is warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The effects of different interpregnancy intervals (IPI), usually stratified to long and short IPIs on subsequent pregnancy outcomes, have been raided as a possible factor affecting pregnancy outcomes during the last decades. Short IPIs, often occurring after adverse pregnancy outcomes, such as stillbirths have been studied [1, 2]. Both short and long IPIs are known to be associated with pregnancy complications, such as gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), gestational hypertension, preterm birth, or perinatal mortality [3, 4]. Multiple studies have assessed the influence of IPI on subsequent pregnancies and its complications. In a recent meta-analysis by Wang et al., [3] short IPI was associated with increased risk for preterm birth, low birth weight, and offspring death [4,5,6]. Moreover, long IPI is known to increase the risk of recurrent pre-eclampsia [4].

Most studies have examined the impact of the length of IPI on the health of both the child and the mother. An interesting study from Australia in 2023 was the first to study this topic with a new perspective [7]. This study investigated the effects of different pregnancy outcomes in the first pregnancy to the subsequent length of the IPI using a large dataset of over 250,000 women [7]. This study found that women with preeclampsia and gestational hypertension in the first pregnancy had slightly longer subsequent IPIs than mothers whose pregnancies were not complicated by these conditions. Otherwise, the knowledge of what influences the length of IPI is very limited [7].

The hypothesis has been that pregnancy complications like gestational diabetes and pre-eclampsia may prolong the subsequent IPI due to the need for health recovery, lifestyle changes, emotional factors, healthcare provider recommendations, and potential fertility considerations, impacting the timing of the next conception. Managing and stabilizing health conditions before attempting another pregnancy is often recommended. The body may need time to recover from the physiological stress it experienced during the first pregnancy. Waiting between pregnancies can help reduce the chances of recurrence and improve overall maternal and fetal outcomes in subsequent pregnancies. This study aimed to study the association between different pregnancy complications at first pregnancy and the length of subsequent IPI.

Materials and Methods

In this retrospective nationwide register-based cohort study, data from the National Medical Birth Register (MBR), maintained by the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare, were used to evaluate the association between different pregnancy complications and the subsequent length of the IPI. The MBR has high quality and coverage, the current coverage being nearly 100% [8, 9]. The study period was from 1 January 2004 to 31 December 2018. The MBR contains data on pregnancies, delivery statistics, and the perinatal outcomes of all births with a birthweight ≥ 500 g or a gestational age ≥ 22 + 0 weeks.

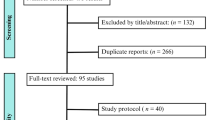

During 2004–2018, a total of 843,466 pregnancies were registered in Finland. We selected all women with first and second pregnancies during our study period from the MBR. Third or later pregnancies of the women included in this study were removed from the data (n = 420,951). Also, women with multiple pregnancies in the first pregnancy (n = 1112) were excluded from the data, as this influences heavily the IPI. Therefore, the remaining study sample consisted of 211,202 women with first and second pregnancies. The IPIs from the day of giving birth in the first pregnancy and the beginning of the second pregnancy for these women were calculated, and the association between pregnancy complications (gestational hypertension, GDM, preterm birth, perinatal mortality, shoulder dystocia) in the first pregnancy and the length of the subsequent IPI was evaluated. In Finland, GDM is diagnosed in the second trimester with a 2 h 75 g oral glucose tolerance test. Preterm birth includes neonates born with gestational age less than 37 + 0 weeks. Perinatal mortality includes neonates who die before the mother gives birth or during the first 7 days after giving birth. The beginning date of the pregnancy was calculated using the date of giving birth and the length of the pregnancy registered in the MBR. The forming of the study sample is shown as a flowchart in Figure 1.

Statistics

The continuous variables were interpreted as means with standard deviations (sd) or as medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) based on the distribution of the data. The categorical variables are presented as absolute numbers and percentages. A logistic regression model was used to assess the association between the pregnancy complication (gestational hypertension, GDM, preterm birth, perinatal mortality, shoulder dystocia) in the first pregnancy and the subsequent length of the IPI between the first and the second pregnancy. Women were divided into short, normal, and long IPIs based on the distribution of the IPI in the study population. Women with IPI length of the IPI in the lower quartal (< 25%) were considered women with short IPIs, women with IPI length in the upper quartal (< 75%) were considered women with long IPIs, and women with IPIs between these as women with normal IPI, which was used as a reference outcome in the logistic regression analyses. The odds for short IPI and the odds for long IPI compared to normal IPI were analyzed separately after each pregnancy complication. Adjusted odds ratios (aOR) with 95% CIs were compared between the groups. The model was adjusted for other background factors, that might have effects on the length of the IPI, such as maternal age, maternal smoking status, and maternal BMI. Also, as cesarean section (CS) is not a causal confounding factor but might have an effect on the length of the IPI [10], we performed an additional analysis with only women with vaginal delivery included. The results of this study are reported according to STROBE guidelines [11]. Statistical analysis was performed using R version 4.0.3.

Ethics

All methods were carried out by Finnish regulations. The Ethical Committee of Tampere University Hospital waived the ethical committee evaluation of all retrospective studies utilizing routinely collected healthcare data, and this decision is based on the law of medical research 488/1999 and the law of patient rights 785/1992. By the Finnish regulations (The law of secondary use of routinely collected healthcare data 552/2019), no informed written consent was required because of the retrospective register-based study design, and the patients were not contacted. Permission for the use of this data was granted by Findata after the evaluation of the study protocol (Permission number: THL/1756/14.02.00/2020).

Results

A total of 211,202 women with first and second pregnancies during our study periods were included in this study. The mean age of women included during the first pregnancy was 27.0 years (sd 4.7). The median IPI among these women was 1.66 years (IQR 1.53). The lower quartile of the IPI was < 1.07 years and the upper quartile was > 2.61 years. Therefore, IPIs under 1.07 years were considered short IPIs, and IPIs longer than 2.61 years were considered long IPIs. During the first pregnancy, a total of 1.8% of women had gestational hypertension, 9.3% had diagnosed GDM, 4.9% had a preterm birth, 0.5% of the neonates died before giving birth or during the first week, and 0.2% of the neonates had shoulder dystocia (Table 1).

(1.07–2.61 years)A total of 52,709 women with short IPI, 105,604 women with normal IPI, and 52,889 women with long IPI were found in the MBR. Women with normal IPI had the lowest proportion of smokers during the first pregnancy (13.1%) when compared to women with short IPI (17.2%) and long IPI (21.1%). During the first pregnancy, women with all IPI lengths had a similar proportion of gestational hypertension (3.0–3.2%) and shoulder dystocia (0.2–0.3%). Women with short IPI had the highest proportion of GDM (10.0%, CI 9.7–10.3%), and women with long IPI had the lowest proportion of GDM (8.7%). Women with normal IPI had the lowest proportion of preterm births (4.5). Short IPI occurred more commonly after neonatal mortality in the first pregnancy (1.4%) (Table 2).

Women with gestational hypertension had higher odds for long IPI (aOR 1.12, CI 1.06–1.19), women with diagnosed GDM had higher odds for short IPI (aOR 1.09, CI 1.09–1.13), and women with preterm delivery had higher odds for short (aOR 1.12, CI 1.07–1.17) and long IPI (aOR 1.12, CI 1.07–1.17). In addition, women with perinatal mortality had notably higher odds for short IPI (aOR 8.05, CI 6.97–9.32) and lower odds for long IPI (aOR 0.30, CI 0.24–0.37). When only women with vaginal delivery were included, similar results as with all pregnancies were observed. However, women with vaginal delivery and gestational hypertension had no longer higher odds for long IPI (aOR 1.10, CI 0.92–1.25) (Table 3).

Discussion

The main findings of this study were that women with gestational hypertension and preterm birth had higher odds for long IPI, and women with diagnosed GDM and perinatal mortality had higher odds for short IPI. We found no evidence of a difference in long or short IPI after shoulder dystocia.

A recent study published in 2023, to the best of our knowledge the first study assessing the effects of pregnancy complications on the subsequent IPI, found out that women with pre-eclampsia and gestational hypertension had slightly longer subsequent IPIs than mothers whose pregnancies were not complicated by these conditions [7]. In addition, this study found no evidence of a difference in IPIs following a diagnosed GDM [7]. However, the lack of confounding in this study might possibly have affected the results, as their data did not include background variables, such as pre-pregnancy BMI, or the smoking status of the mother, which are included in our analysis. Also, including only vaginal deliveries in this study showed no higher odds for long IPI among women with gestational hypertension, meaning that CS as a mode of delivery is most likely a major factor in increasing the length of the IPI among women with gestational hypertension. Based on our results, women with gestational hypertension had also higher odds for long-term IPI, which is in line with the results of this previous study. Interestingly, also preterm birth was associated with longer subsequent IPI. One possible explanation for this could be that they may prioritize allowing more time between pregnancies to reduce the risk of another preterm birth, as previous preterm birth is known to be a major risk factor for another preterm birth [12]. Also, neonates born very preterm (gestational age < 32 weeks) have truly long hospitalization and more challenging childhood. According to previous literature, medication use, hospital readmission, and clinic visits occurred frequently in these children during the first 3 years and were commonly due to respiratory conditions [13]. This might also be one factor contributing to a longer IPI. In addition, pregnancy complications are known to increase the incidence of fear of childbirth, which is known to decrease the subsequent birth rate in Finland, which might be a contributing factor to longer IPI [14, 15].

The odds for short IPI were markedly higher and the odds for long IPI were markedly lower among women with neonatal mortality in the first pregnancy in our study. Women who experience neonatal mortality in their first pregnancy may opt for shorter IPIs due to emotional resilience or because they have a heightened sense of urgency to try again. Biological factors, societal expectations, and the need for emotional healing might also influence this decision. In addition, women with GDM and preterm delivery had higher odds for short IPI in our study. However, the exact reason for this remains unknown, but the increased risk for complications and neonatal mortality among these women [16] might have had effects on the increased odds for short IPI. Previous studies have revealed that a mother’s age, socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, and marital status are among the factors either delaying or shortening IP [17,18,19]. Despite these, the literature behind the effects of non-background factors, such as pregnancy complications, is truly lacking, and therefore, this topic requires further research. Also, the exact reason behind these variations of IPIs after different outcomes is only speculative and cannot be identified in our data. Therefore, future studies utilizing, e.g., more specific questionnaires could be used to study the etiology of this topic.

The strength of our study is that the register data used in our study are routinely collected nationally in structured forms with consistent instructions, which ensures good coverage (over 99%) and reduces possible reporting and selection biases. Our data consisted of a total of 481 497 women with 843,466 pregnancies, which allows us to analyze a large sample size. Also, the study period was nearly 15 years, which is much longer than that of most previous studies. In addition, the latest study concluded that their study was not able to take some of the confounding variables, such as smoking and pre-pregnancy BMI, into account,[7] which are included in our study. The main limitation of our study is the missing clinical information on patients, meaning that the majority of comorbidities for the women remain unknown. Also, women with CS most likely have an incidence of GDM (fetal macrosomia is more common) or pre-eclampsia, meaning that excluding women with CS may cause imprecisions in terms of these complications.

Conclusion

Women with gestational hypertension and preterm birth had higher odds for long IPI, and women with diagnosed GDM and perinatal mortality had higher odds for short IPI. We found no evidence of a difference in the length of the IPI for women with shoulder dystocia. These results are in line with the results of the previous study, but due to limitations of this study, such as retrospective study design and missing clinical information on patients, more research on this topic is required using more specific datasets; e.g., questionnaires on women with adverse pregnancy outcomes are required.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Findata, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of Findata (url Findata.fi, email info@Findata.fi). The corresponding author (email matias.vaajala@tuni.fi) can be contacted for the data with a reasonable request.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CS :

-

Cesarean section

- GDM :

-

Gestational diabetes

- IPI :

-

Interpregnancy interval

- MBR :

-

The National Medical Birth Register

References

Kangatharan C, Labram S, Bhattacharya S. Interpregnancy interval following miscarriage and adverse pregnancy outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2017;23(2):221–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmw043.

Tessema GA, Håberg SE, Pereira G, Regan AK, Dunne J, Magnus MC. Interpregnancy interval and adverse pregnancy outcomes among pregnancies following miscarriages or induced abortions in Norway (2008–2016): a cohort study. PLOS Med. 2022;19(11):e1004129. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1004129.

Wang Y, Zeng C, Chen Y, et al. Short interpregnancy interval can lead to adverse pregnancy outcomes: a meta-analysis. Front Med. 2022;9:922053. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.922053.

Cormick G, Betrán AP, Ciapponi A, Hall DR, Hofmeyr GJ, calcium and Pre-eclampsia Study Group. Inter-pregnancy interval and risk of recurrent pre-eclampsia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Health. 2016;13(1):83. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-016-0197-x.

Schummers L, Hutcheon JA, Hernandez-Diaz S, et al. Association of short interpregnancy interval with pregnancy outcomes according to maternal age. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(12):1661–70. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4696.

Hanley GE, Hutcheon JA, Kinniburgh BA, Lee L. Interpregnancy interval and adverse pregnancy outcomes: an analysis of successive pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(3):408–15. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000001891.

Gebremedhin AT, Regan AK, Håberg SE, Luke Marinovich M, Tessema GA, Pereira G. The influence of birth outcomes and pregnancy complications on interpregnancy interval: a quantile regression analysis. Ann Epidemiol. 2023;85:108–112.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2023.05.011.

Gissler M, Shelley J. Quality of data on subsequent events in a routine Medical Birth Register. Med Inform Internet Med. 2002;27(1):33–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/14639230110119234.

Gissler M, Teperi J, Hemminki E, Meriläinen J. Data quality after restructuring a national medical registry. Scand J Soc Med. 2016;23(1):75–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/140349489502300113.

Kawakita T, Franco S, Ghofranian A, Thomas A, Landy HJ. Association between long interpregnancy intervals and cesarean delivery due to arrest disorders. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2020;2(3):100103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100103.

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(4):344–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008.

Tingleff T, Vikanes Å, Räisänen S, Sandvik L, Murzakanova G, Laine K. Risk of preterm birth in relation to history of preterm birth: a population-based registry study of 213 335 women in Norway. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2022;129(6):900–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.17013.

Siffel C, Hirst AK, Sarda SP, et al. The clinical burden of extremely preterm birth in a large medical records database in the United States: complications, medication use, and healthcare resource utilization. J Matern-Fetal Neonatal Med Off J Eur Assoc Perinat Med Fed Asia Ocean Perinat Soc Int Soc Perinat Obstet. 2022;35(26):10271–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2022.2122035.

Vaajala M, Liukkonen R, Kuitunen I, Ponkilainen V, Mattila VM, Kekki M. Factors associated with fear of childbirth in a subsequent pregnancy: a nationwide case–control analysis in Finland. BMC Womens Health. 2023;23(1):34. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-023-02185-7.

Vaajala M, Liukkonen R, Ponkilainen V, Mattila VM, Kekki M, Kuitunen I. Birth rate among women with fear of childbirth: a nationwide register-based cohort study in Finland. Ann Epidemiol. 2023;79:44–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2023.01.011.

Jain U, Singhal K, Jain S, Jain D. Risk factor for gestational diabetes mellitus and impact of gestational diabetes mellitus on maternal and fetal health during the antenatal period. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2021;10(9):3455–61. https://doi.org/10.18203/2320-1770.ijrcog20213169.

Kaharuza FM, Sabroe S, Basso O. Choice and chance: determinants of short interpregnancy intervals in Denmark. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80(6):532–8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11380289/. Accessed 17 Sept 2023.

CheslackPostava K, Winter AS. Short and long interpregnancy intervals: correlates and variations by pregnancy timing among U.S women. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2015;47(1):19–26.

Gemmill A, Lindberg LD. Short interpregnancy intervals in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(1):64–71. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182955e58.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Tampere University (including Tampere University Hospital).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MV and JT wrote the initial manuscript. IK and MV undertook the study design. VM supervised the study. Each author commented on the manuscript during the process and confirmed the final version to be submitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

All methods were carried out in accordance with Finnish regulations. The Ethical Committee of Tampere University Hospital waived the ethical committee evaluation of all retrospective studies utilizing routinely collected healthcare data, and this decision is based on the law of medical research 488/1999 and the law of patient rights 785/1992. In accordance with Finnish regulations (the law of secondary use of routinely collected healthcare data 552/2019), no ethical informed written consent was required because of the retrospective register-based study design, and the patients were not contacted. Both the National Medical Birth Register (MBR) and the Care Register for Health Care have the same unique pseudonymized identification number for each patient. Permission for the use of this data was granted by Findata after the evaluation of the study protocol (permission number: THL/1756/14.02.00/2020).

Consent for Publication

All participants have consented to publication, at the time of consent to participate.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vaajala, M., Tarkiainen, J., Mattila, V.M. et al. The Association Between Pregnancy Complications and Subsequent Interpregnancy Interval: a Nationwide Register-Based Quantile Logistic Regression Analysis. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 5, 281 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42399-023-01625-7

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42399-023-01625-7