Abstract

This paper endogenizes pro-entrepreneurship policies in a model where voters choose the strength of these policies and entrepreneurs generate social returns which benefit the median voter. In the model, incumbent firms who are harmed by the greater competition that this policy promotes can push back in two ways: via corruption and persuasion. Specifically, they can bribe elected politicians to break their campaign promises; and they can allocate some of their rents to corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives that also benefit voters. The model predicts that corruption which weakens pro-entrepreneurship policy can be completely neutralized by a forward-looking median voter—without removing the incentive among incumbent firms to bribe politicians. In this way, endogenizing entrepreneurship policy can destroy any relationship between corruption and entrepreneurship. Corporate social responsibility initiatives modify this prediction, which provides a novel rationale for CSR that appears to be new to the literature as well.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The theoretical analysis in this article is also likely to be less applicable to developing countries, for two major reasons. First, many (though not all) developing countries suffer from weak institutions, and lack robust democracies allowing the general public to vote for and determine public entrepreneurship policy. My model in contrast applies to a setting where voters determine entrepreneurship policy, and respond to corporate and political corruption through the ballot box. Second, positive spillovers from entrepreneurship to the general public are generally less pronounced in developing countries, where unproductive and self-serving business ownership is common (Morck & Yeung, 2004); where most productive entrepreneurship is of the necessity type (Acs et al., 2008); and where entrepreneurs typically operate a long way behind the technological frontier (Acemoglu et al., 2006). In contrast, a central assumption in my model is positive spillovers from entrepreneurship.

An alternative modeling assumption would be to make \(\lambda\) heterogeneous instead of \(\gamma\), e.g., to reflect the fact that some voters benefit more from some entrepreneurial innovations than others (e.g., workers in incumbents who are disrupted by innovations gain less than workers in the firms introducing the innovations). This modeling choice would change neither the logic of the model nor the key results that follow.

This is also a parsimonious way of representing inter-temporal issues like policy deviations harming P’s re-election prospects in subsequent elections.

We assume that the constitution punishes politicians caught accepting bribes, but shows leniency towards the incumbent firm offering the bribes. Asymmetric punishment of this kind can be more effective than symmetric punishments where both parties have incentives to collude to make detection more difficult.

For details, see https://www.transparency.org/en/news/how-cpi-scores-are-calculated.

References

Acemoglu, D. (2008). Oligarchic versus demographic societies. Journal of the European Economic Association, 6(1), 1–44.

Acemoglu, D., Aghion, P., & Zilibotti, F. (2006). Distance to frontier, selection, and economic growth. Journal of the European Economic Association, 4(1), 37–74.

Acs, Z. J., & Audretsch, D. B. (1988). Innovation in large and small firms: An empirical analysis. American Economic Review, 78, 678–90.

Acs, Z. J., Desai, S., & Hessels, J. (2008). Entrepreneurship, economic development and institutions. Small Business Economics, 31, 219–34.

Audretsch, D. B. (2007). The Entrepreneurial Society. New York: Oxford University Press.

Audretsch, D. B., & Moog, P. (2022). Democracy and entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 46(2), 368–92.

Audretsch, D. B., Belitski, M., Chowdhury, F., & Desai, S. (2021). Necessity or opportunity? Government size, tax policy, corruption, and implications for entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 58(4), 2025–42.

Bardhan, P. (1997). Corruption and evidence: A review of issues. Journal of Economic Literature, 35, 1320–46.

Baumol, W. J. (1990). Entrepreneurship: Productive, unproductive, and destructive. Journal of Political Economy, 98, 893–921.

Becker, G. S. (1983). A theory of competition among pressure groups for political influence. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 98(3), 371–400.

Belitski, M., Chowdhury, F., & Desai, S. (2016). Taxes, corruption, and entry. Small Business Economics, 47, 201–16.

Champeyrache, C. (2018). Destructive entrepreneurship: The cost of the mafia for the legal economy. Journal of Economic Issues, 52(1), 157–72.

Chowdhury, F., Audretsch, D. B., & Belitski, M. (2019). Institutions and entrepreneurship quality. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 43(1), 51–81.

Davis, S. J., & Henrekson, M. (1997). Industrial policy, employer size and economic performance in Sweden. In R. B. Freeman, R. Topel, & B. Swedenborg (Eds.), The welfare state in transition. Chicago IL: University of Chicago Press.

Desai, S., Eklund, J. E., & Lappi, E. (2020). Entry regulation and persistence of profits in incumbent firms. Review of Industrial Organization, 57(3), 537–58.

Dutta, N., & Sobel, R. (2016). Does corruption ever help entrepreneurship? Small Business Economics, 47, 179–99.

Farè, L., Audretsch, D. B. & Dejardin, M. (2023). Does democracy foster entrepreneurship?. Small Business Economics, In: press.

Fogel, K., Hawk, A., Morck, R., Yeung, B., et al. (2006). Institutional obstacles to entrepreneurship. In M. Casson (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of entrepreneurship (pp. 540–79). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gehrig, T., & Stenbacka, R. (2007). Information sharing and lending market competition with switching costs and poaching. European Economic Review, 51, 77–99.

Gennaioli, C., & Tavoni, M. (2016). Clean or dirty energy: Evidence of corruption in the renewable energy sector. Public Choice, 166, 261–90.

Gohmann, S. F. (2016). Why are there so few breweries in the South? Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 40(5), 1071–92.

Guerriero, M. (2019). The labor share of income around the world: Evidence from a panel dataset. Labor Income Share in Asia (pp. 39–79). Singapore: Springer.

Haltiwanger, J., Jarmin, R., & Miranda, J. (2013). Who creates jobs? Small versus large versus young. Review of Economics and Statistics, 95(2), 347–61.

Henrekson, M. (2005). Entrepreneurship: A weak link in the welfare state? Industrial & Corporate Change, 14, 437–67.

Holmes, T. J., & Schmitz, J. A. (2001). A gain from trade: From unproductive to productive entrepreneurship. Journal of Monetary Economics, 47, 417–46.

Hottenrott, H., & Richstein, R. (2020). Start-up subsidies: Does the policy instrument matter? Research Policy, 49(1), 103888.

Itskhoki, O., & Moll, B. (2019). Optimal development policies with financial frictions. Econometrica, 87(1), 139–73.

Klein, P. G., Holmes, R. M., Jr., Foss, N., Terjesen, S., & Pepe, J. (2022). Capitalism, cronyism, and management scholarship: A call for clarity. Academy of Management Perspectives, 36(1), 6–29.

Lucas, R. E. (1978). On the size distribution of business firms. Bell Journal of Economics, 9, 508–23.

McChesney, F. S. (1987). Rent extraction and rent creation in the economic theory of regulation. Journal of Legal Studies, 16(1), 101–18.

Morck, R., & Yeung, B. (2004). Family control and the rent-seeking society. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 28(4), 391–409.

Murphy, K. M., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. (1993). Why is rent-seeking so costly to growth? American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings, 83, 409–14.

Olson, M. (1971). The logic of collective action: Public goods and the theory of groups. Second Printing, Harvard University Press.

Parker, S. C., et al. (2007). Policy-makers beware! In D. B. Audretsch (Ed.), The international handbook of entrepreneurship policy research. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Parker, S. C. (2018). The economics of entrepreneurship (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pástor, L., & Veronesi, P. (2020). Political cycles and stock returns. Journal of Political Economy, 128(11), 4011–45.

Peltzman, S. (1976). Toward a more general theory of regulation. Journal of Law and Economics, 19(2), 211–40.

Perotti, E., & Volpin, P. (2005). Lobbying on entry, CEPR Discussion Paper 4519. London

Persson, T. (1998). Economic policy and special interest politics. Economic Journal, 108(447), 310–27.

Rajan, R., & Zingales, L. (2003). The great reversal: The politics of financial development in the 20th century. Journal of Financial Economics, 69, 5–50.

Snyder, J. M., Jr. (1990). Campaign contributions as investments: The US House of Representatives, 1980–1986. Journal of Political Economy, 98(6), 1195–1227.

Stigler, G. J. (1971). The theory of economic regulation. Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science, 2(1), 3–21.

Takii, K. (2008). Fiscal policy and entrepreneurship. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 65, 592–608.

Thomson, R., et al. (2017). The fulfillment of parties’ election pledges: A comparative study on the impact of power sharing. American Journal of Political Science, 61(3), 527–542.

Tollison, R. D. (2000). The rent-seeking insight. In: Public choice essays in honor of a maverick scholar: Gordon Tullock (pp. 13–28). Springer.

Tullock, G. (1967). The welfare costs of tariffs, monopolies, and theft. Economic Inquiry, 5(3), 224–32.

Tzur, A. (2019). Uber Über regulation? Regulatory change following the emergence of new technologies in the taxi market. Regulation & Governance, 13(3), 340–61.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendices

1.1 Appendix 1: Illustration with specific functional forms

To illustrate the model, consider the following specific functional forms:

The third equation specifies the distribution of X as Pareto, following Itskhoki and Moll (2019).

Using these functional forms, we obtain \({\hat{x}}=w/p\) and two reduced form simultaneous equations in p(z) and z(p), which are both positive, increasing and convex functions:

These can be solved for the structural equations

With these functional forms, the solution of the Nash bargaining game is

Consistent with Proposition 1, we obtain

with the other three derivatives identical to those in the text.

To illustrate Proposition 3, note that the solution when \(\theta >0\) is

with

since \(\eta >1\).

1.2 Appendix 2: Cross-country correlations

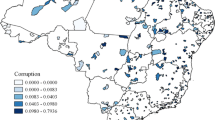

Corruption occurs when public officials are neither required to disclose their finances and potential conflicts of interest, nor face serious consequences, when using their public offices for private gain. These outcomes and facilitators are captured by Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), a harmonized index that facilitates international comparisons, where higher values indicate lower levels of lobbying and corruption.Footnote 5 Another corruption index is the World Governance Indicator, WGI, ’Control of Corruption, CC index, which is known to be highly correlated with the CPI Belitski et al., 2015; (Dutta & Sobel, 2016; Audretsch et al., 2021).

A harmonized cross-national measure of entrepreneurship is the index of total entrepreneurship activity (TEA). TEA is the percentage of adults aged 18–64 engaged in early-stage entrepreneurial activity at a given point in time. Data were taken from https://www.gemconsortium.org/file/open?fileId=50691. Figure 1 plots the CPI against TEA for 22 OECD countries for which data were available in 2019; Fig. 2 plots the WGI CC index against TEA for the same set of countries in the same year. Higher values of CPI and WGI indicate lower levels of corruption.

If corruption retards entrepreneurship we would expect to observe a positive empirical relationship between entrepreneurship and these two inverse corruption measures. However, Figures 1 and 2 show that if anything the opposite is the case. There is if anything a small negative relationship between CPI and TEA; but it is not statistically significant (in a double log regression, \({\hat{\beta }}=-0.09\), \(p=0.44\)). The same is true for the WGI CC index: the regression results also indicate a negatively signed and insignificant relationship (\({\hat{\beta }} =-0.09\), \(p=0.57\)). Moreover, in additional plots (not reported) similar results apply using an ’opportunity entrepreneurship’ variant of the TEA measure. Thus, among developed countries where democratic institutions are generally well entrenched, we see no evidence of a cross-country relationship between entrepreneurship and political corruption.

1.3 Appendix 3: Conditions for optimal \(\theta\)

Absent CSR, the incumbent makes profits of \(\Pi (1-z(p_m))\). With CSR, denote optimal policy by \(p^* \le p_m\) [see Proposition 3]. The marginal cost to an incumbent of expending a fraction \(\theta\) of profits on CSR is obviously \(\theta \Pi (1-z(p_m))\). The marginal benefit to them of CSR which replaces \(p_m\) with \(p^*\) is

Hence the incumbent’s objective function is

With choice variable \(\theta\), the Karush–Kuhn–Tucker conditions for a maximum are:

If \(\theta ^*>0\), the second order condition for a maximum is

A sufficient condition for this inequality to hold is \(\frac{d^2 p^*}{d\theta ^2}>0\). As noted at the end of "Appendix 1", this condition holds for the specific functional forms analyzed there. In general, however, a corner solution \(\theta ^*=0\) can arise if even a small profit share is too costly relative to the value of the policy change it induces via shifted voter choices. Then corporations do not find any CSR worthwhile, and complete policy neutralization can be expected.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Parker, S.C. Democracy, corruption, and endogenous entrepreneurship policy. Public Choice 198, 361–376 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-023-01133-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-023-01133-1