Abstract

Living up to the expectations of the JIBS Decade Award, Goerzen, Asmussen, and Nielsen’s 2013 paper not only introduced the literature on global cities to the international business (IB) community but continues to be generative. In their “Retrospective and a Looking Forward” paper 10 years later, the authors highlight megatrends about people, places and things, and new contexts and alternative perspectives, and they encourage further new ways of thinking about global cities and IB. This commentary expands upon their framework of three overlapping circles of global issues, global organizations, and global locations, by drawing especially from recent experiences in the U.S. and research in economic geography and allied fields. Facing global issues of climate change, human rights, health, housing, and the impacts of digital technologies on work, cities offer prospects of responding to these challenges, a context for multinational enterprises (MNEs) to consider. Against the backdrop of large-scale global migrations of unskilled, mostly contract, workers to global cities in developed economies, recruitment agencies and advocacy groups for migrants are global organizations as important as MNEs. Finally, the fluidity of physical boundaries, as illustrated by city-regions, world regions beyond traditional Western-centric perspectives, and intra-national variations, is key to analyzing global locations.

Résumé

À la hauteur des attentes du JIBS Decade Award, l'article de Goerzen, Asmussen et Nielsen de 2013 a non seulement introduit la littérature sur les villes mondiales dans la communauté des affaires internationales (International Business - IB), mais continue d'être génératif. Dix ans plus tard, dans leur article intitulé "Retrospective and a Looking Forward", les auteurs mettent en évidence les mégatendances concernant les personnes, les lieux et les choses, ainsi que les nouveaux contextes et les perspectives alternatives, et ils encouragent de nouvelles façons de penser les villes mondiales et le domaine de l’IB. Ce commentaire développe leur cadre théorique de trois cercles superposés de défis mondiaux, d'organisations mondiales et de localisations mondiales, en s'appuyant notamment sur des expériences récentes aux États-Unis et les recherches en géographie économique et dans d'autres domaines connexes. Face aux enjeux mondiaux du changement climatique, des droits de l'homme, de la santé, du logement et de l'impact des technologies numériques sur le travail, les villes offrent des perspectives de réponse à ces défis, un contexte que les entreprises multinationales (Multinational Enterprises - MNEs) doivent prendre en considération. Dans le contexte des migrations mondiales à grande échelle de travailleurs non qualifiés, principalement contractuels, vers les villes mondiales des économies développées, les agences de recrutement et les groupes de défense des migrants sont des organisations mondiales aussi importantes que les MNEs. Enfin, la fluidité des frontières physiques, illustrée par les villes-régions, les régions du monde au-delà des perspectives traditionnelles centrées sur l’Occident et les variations intra-nationales, constitue un élément clé de l'analyse des localisations mondiales.

Resumen

Cumpliendo las expectativas del Premio JIBS de la Década, el artículo de Goerzen, Asmussen y Nielsen de 2013 no solo introduce la literatura sobre ciudades globales en la comunidad de Negocios Internacionales (IB por sus iniciales en inglés), sino que sigue siendo enriquecedor. En su artículo “Retrospectiva y una mirada al futuro”, diez años después, los autores destacan las megatendencias sobre las personas, los lugares y las cosas, así como los nuevos contextos y las perspectivas alternativas, y animan a adoptar nuevas formas de pensar sobre las ciudades globales y los negocios internacionales. Este comentario amplía su marco de tres círculos superpuestos de asuntos globales, organizaciones globales y lugares globales, basándose especialmente en experiencias recientes en Estados Unidos y en la investigación en geografía económica y campos afines. Frente a los problemas globales del cambio climático, los derechos humanos, la salud, la vivienda y las repercusiones de las tecnologías digitales en el trabajo, las ciudades ofrecen perspectivas de respuesta a estos retos, un contexto que las empresas multinacionales (MNEs por sus iniciales en inglés) deben considerar. Sobre el trasfondo de las migraciones mundiales a gran escala de trabajadores no cualificados, en su mano de obra, a las ciudades globales de las economías desarrolladas, las agencias de contratación y los grupos de defensa de los migrantes son organizaciones mundiales tan importantes como las empresas multinacionales. Por último, la fluidez de las fronteras físicas, como ilustran las ciudades-región, las regiones del mundo más allá de las perspectivas occidentales-céntricas tradicionales y las variaciones intranacionales, es clave para analizar las ubicaciones globales.

Resumo

Fazendo jus à expectativa do Prêmio JIBS da década, o artigo de 2013 de Goerzen, Asmussen e Nielsen não só introduziu a literatura sobre cidades globais à comunidade de Negócios Internacionais (IB), mas continua a ser multiplicativo. No seu artigo “Retrospective and a Looking Forward”, dez anos mais tarde, os autores destacam megatendências sobre pessoas, lugares e coisas, e novos contextos e perspectivas alternativas, e incentivam novas formas de pensar sobre cidades globais e IB. Este comentário expande seu modelo de três círculos sobrepostos de questões globais, organizações globais e locais globais, recorrendo especialmente a recentes experiências nos EUA e à pesquisa em geografia econômica e campos afins. Enfrentando questões globais de alterações climáticas, direitos humanos, saúde, habitação e os impactos de tecnologias digitais no trabalho, cidades oferecem perspectivas de resposta a estes desafios, um contexto a ser considerado por empresas multinacionais (MNEs). No contexto de globais migrações de trabalhadores não qualificados em grande escala, na sua maioria contratados, para cidades globais em economias desenvolvidas, agências de recrutamento e grupos de defesa de migrantes são organizações globais tão importantes quanto MNEs. Finalmente, a fluidez de fronteiras físicas, ilustrada por cidades-regiões, por regiões mundiais que vão além de perspectivas tradicionais centradas no ocidente e pelas variações intranacionais, é fundamental para a análise de locais globais.

摘要

Goerzen、Asmussen和Nielsen2013年发表的论文没有辜负JIBS十年奖的期望, 不仅向国际商业(IB)社区介绍了关于全球城市的文献, 而且继续具有生产力。十年后,在他们的论文“回顾与展望”中, 作者强调了关于人、地方和事物的大趋势, 以及新情境和替代视角, 并鼓励有关全球城市和IB进一步的新思维方式。这篇评论通过特别借鉴美国最近的经验以及经济地理学和相关领域的研究, 扩展了他们关于全球问题、全球组织和全球位置的三重叠圈框架。面对气候变化、人权、健康、住房和数字技术对工作的影响等全球问题, 城市提供了应对这些挑战的前景, 这是跨国企业 (MNE) 需要考虑的情境。在非技术工人(主要是合同工)大规模全球迁移到发达经济体里的全球城市的背景下, 移民招聘机构和倡导团体是与MNE一样重要的全球组织。最后, 正如城市区域、超越传统的西方中心论的世界区域和国家内部差异所示, 物理边界的流动性是分析全球位置的关键。

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

For the past 27 years, annually the Journal of International Business Studies (JIBS) has awarded the Decade Award to honor the most influential article published in the journal 10 years prior. The Decade Award is an excellent concept, as it calls attention to the lasting impact of research. In addition, the special session at the Academy of International Business Annual Meeting dedicated to the JIBS Decade Award is a wonderful opportunity for the award’s authors to reflect on changes in the previous 10 years and share how they look forward to the future about the pertinent research. The Academy of Management also gives out Decade Awards, through four of its six journals. Another professional organization that regularly honors publications with Decade Awards is the International Studies Association, whose Best Book of the Decade Award is given to the best book published in international studies over the last decade.

Yet, and interestingly, it appears that Decade Awards is not a common practice to recognize influential publications among many other professional academic organizations. While it is not clear why this is so, it may be that one of the reasons is that it is difficult to measure influence. Quantitative metrics like citation indices are helpful, but only to a certain extent. Perhaps more important is a qualitative perspective of influence. More precisely, how do we know things are different after the publication of the work?

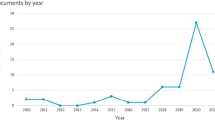

The paper “Global cities and multinational enterprise location strategy” by Goerzen, Asmussen, and Nielsen (2013), is an outstanding example that clears both the quantitative and qualitative bars of influence with flying colors. As pointed out in their retrospective paper, “Global Cities: Retrospective and a Look Forward” (Goerzen et al., 2024), the 2013 paper generated three times as many citations between 2018 and 2022 compared to 2013–2017, signifying its generative impact on international business (IB) research that is beyond the short term. This generativity is a function of the qualitative influence of the paper, namely, it has introduced new perspectives, new ways of thinking, and above all new interdisciplinary approaches that enrich research across disciplinary borders. In particular, the paper challenges IB researchers to learn about and engage the literature in economic geography and allied fields such as urban studies and political economy, especially works on global cities. Prior to the 2013 paper, IB research largely ignored the city as a unit of analysis, let alone global cities. The Decade Award paper single-handedly put global cities on the IB and management research agenda, as indicated by the sharp increase in IB publications on global cities in the past 10 years. The scale of impact is therefore field-wide, making the paper fully deserving of the Decade Award.

Goerzen et al. (2013) connect the liability of foreignness (LOF) with multinational enterprises’ (MNEs) locational choice. LOR primarily refers to complexity, uncertainty and discrimination: complexity of operations arises from distance-related challenges such as travel, coordination and time-zone difference; uncertainty is due to lack of familiarity within the local environment; and discrimination stems from economic nationalism and lack of legitimacy of foreign firms. To MNEs, these are all additional costs associated with doing business abroad. Through an econometric analysis of Japanese MNEs, the authors conclude that “while demand-driven market seeking and market-serving activities, such as sales and distribution, are more likely to locate in global cities, supply-driven efficiency-seeking and asset seeking activities, such as production and R&D, are more likely to be located outside the global cities, either in the metropolitan areas surrounding these cities, or in the peripheral rural areas.” Their overall argument is that global cities’ distinct properties, in particular global interconnectedness, cosmopolitanism, and abundance of advanced producer services, help MNEs overcome the costs of overseas operations.

In their retrospective paper, Goerzen et al. (2024) bring us up to date in the connections between LOF and global cities, by highlighting the megatrends about people, places, and things that are shaping global cities. In JIBS and other IB and management journals, these megatrends have also gained increasing attention. Megatrends about people include shifts in demography and social concerns, such as migration, global competition for talent and labor, rising awareness of social injustices, and political engagement to address well-being and other issues. Regarding places, the authors highlight the changing natural environment, especially degradation of the natural environment and diminishing environmental resources, as well as responses that aim at promoting sustainable development and reducing the environmental impacts of urban activities. In JIBS, for example, Global Sustainability has been added as a subdomain of IB (Tung, 2023). As for things, a major megatrend is the rise of digital technologies, enabling improved technological capabilities, wider applications, falling costs, and the rise of smart cities. This is once again reflected in the expanding scope of JIBS, which has added Industry 4.0 as another subdomain that merits research attention (Tung, 2023). In other words, the contexts for cities, including global cities, have changed. Future research ought to consider these new contexts.

In addition, looking ahead to the future, the authors call for “Generative IB research,” which they place at the intersection of three overlapping circles in a Venn diagram. These three circles represent global issues, global organizations, and global locations, a framework for them to consider new perspectives for research on global cities and IB. Rather than focusing on LOF, which continues to be an important topic in IB and consideration for MNEs, this commentary adopts the framework in the retrospective paper, with the goal of motivating continued generativity. In short, this commentary aims at highlighting and expanding on some of the megatrends, new contexts, and alternative perspectives identified in the retrospective paper, and drawing especially from recent experiences in the U.S. and research from economic geography and allied fields.

Global issues

For the global issues circle in the Venn diagram, the authors cite themes such as social justice and human rights, environmental stewardship, individual well-being, and digitalization. These are indeed among the most urgent global challenges, which are manifested across geographic scales: the neighborhood, the city, the region, and the globe. Social justice, for example, involves how marginalized groups are treated in different parts of the city but also systemic racism and discrimination around the world. All the same, cities have significant roles to play as sources and sites of challenges and hopefully as problem-solvers as well.

Issues of social justice and human rights are by no means new. Unfortunately, it is often the case that little attention is paid to these issues until and unless dramatic events, usually involving violence, take place. One of those turning points was the cold-blooded murder of George Floyd in May 2020 in Minneapolis. Floyd was just one of many Black people in the U.S. who died because of police brutality, but the 9 min during which a police officer’s knee was pressed against his neck until he suffocated to death was caught on camera for the world to see. Perhaps because of the video, but also reflecting the megatrend of rising awareness of social injustices, Floyd’s murder sparked the largest racial justice protests in the U.S. since the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s. However, the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement went far beyond the borders of the U.S. – it inspired a global reckoning with racism as Floyd's death became a symbol of the intolerance and injustice people face at home. The BLM protests in the U.S. have been joined by anti-racist protesters all over the world, from Cape Town to Seoul, from London to Mexico City, and from Bangkok to Sydney, not only lending their support to BLM protests in solidarity with Black Americans, but also drawing global attention to their deeply rooted struggles against systemic racism in their own societies.

The Paris Agreement, adopted in 2015 with the goal of holding the increase in the global average temperature to below 2°C above pre-industrial levels, is still the most referred to international standard to be met, but this standard is now widely understood to be insufficient. That July 2023 is the planet’s hottest month on record speaks volumes about the need for urgent actions, by not only countries but cities. Indeed, Goerzen et al. (2024) highlight the role of global cities in environmental stewardship, citing the “clear ascendance of global cities as leaders in … [addressing] climate change.” A good example is the C40 network of mayors, from nearly 100 cities across the world, many of which are global cities, that aims at driving urban action that reduces greenhouse gas emissions and climate risks. This is an existential threat to humankind for which cities around the world should address with urgency not just individually but collectively and quickly.

Cities are also where issues about people’s well-being in terms of health, mental health, housing, and work are raised. The COVID-19 pandemic exposed the vulnerability of large cities to health threats. Hamidi, Sabouri, and Ewing (2020) report that metropolitan population is one of the most significant predictors of COVID-19 infection rates in the U.S.; larger metropolitan areas have higher infection and higher mortality rates. What’s more, they found that connectivity matters more than density in the spread of the pandemic, referring to both connectivity within the metropolitan areas as well as exchanges across borders such as tourists and businesspersons. This has special implications for global cities because they are not only large in size but are highly connected with the world. In addition, Lai and Huang (2022) show that even though large cities possibly possess more superior heath care systems, they are more vulnerable than smaller ones due to the enormous pressure on their health care systems. These studies provide convincing explanations for why, of all U.S. cities, New York City has the highest rate of confirmed deaths due to COVID-19. Approaches to address the pandemic have varied widely across cities and countries. While complete lockdowns have been used in some cities, Lai and Huang (2022) point out that radical and indiscriminate responses are a double-edged sword; although these measures appear to be useful in slowing down the spread, they would seriously disrupt personal livelihoods, urban development, and even long-term socioeconomic robustness of the nation.

Homelessness is an increasingly challenging phenomenon in U.S. cities as well as many parts of North America. The Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority reported in 2020 that about 25 percent of all homeless adults in Los Angeles County suffer from severe mental illnesses such as psychotic disorders and schizophrenia, and a 2022 study by the RAND Corporation found that 54% of the unhoused in Los Angeles reported having a mental health condition (Harter & Scauzillo, 2023).

Finally, cities, especially their downtowns, are experiencing an exodus of office workers who can and want to work remotely. Remote or hybrid work was rare before the pandemic but became a welcome option by necessity and facilitated by digital technologies during the pandemic. The emptying of downtown San Francisco, in particular, has been widely reported (e.g., Dougherty & Goldberg, 2022). This is a legacy of the “forced experiment for employment, shopping, workplace and residence choice, and community, of the lockdown” during the pandemic (Florida et al., 2023: 1511). As the pandemic subsides, however, employees asked to return to the workplace may be reluctant to do so, and some may resign, a factor of the “Great Resignation” in the U.S. (Tessema et al., 2022: 161). However, the departure from cities also is rooted in the “New Urban Crisis” that cities in the 21st century face, including unaffordability, segregation, inequality, among others (Florida, 2017). In this light, while employees’ expectations of and demand for remote and hybrid work are made possible by the pandemic-forced experiment and digital technologies, they also reflect employees’ advocacy for their well-being.

In short, while global cities face many global challenges, they also offer prospects for generating responses to these challenges. To MNEs, locating in global cities abroad may alleviate the LOF because of their international interconnectedness, advanced producer services, and cosmopolitan environment, as illustrated powerfully in the Decade Award paper, but this strategy also increasingly must consider these cities’ other and evolving properties. While it is yet unclear in what ways global issues described above – social justice, human rights, environmental stewardship, individual well-being, and digitalization – among others, affect LOF, what is clear is that globalization as manifested via these issues shapes global cities. Research on global cities, and therefore IB, needs to consider these global issues.

The discussion in this section thus far has focused on some of the most challenging global issues, as manifestations of megatrends, that face MNEs. The other side of the coin is what can and should MNEs do about that. While this question does not constitute the core of this commentary, it is worth mentioning that some studies have indeed highlighted MNEs as change agents. For example, taking an economic geographic perspective and using the terms transnational corporations (TNCs) interchangeably with MNEs, Yeung (2009) argues that they are modern institutions of capitalism and as such are active and dynamic agents creating and sustaining agglomeration. Surely economies of agglomeration underpin the creation of global cities, but in Yeung’s view TNCs’ impact is felt across scales, “from the urban to the regional and the global” (p. 2020). Mitchell (2010) examines multinational corporations (MNCs) as a social change agent that affects the host country, in particular its level of environmentalism. One motivating factor is the host country’s quest for legitimacy in the global business environment (Kwok & Tadesse, 2006). MNEs from emerging economics can also be change agents, as shown by Bhaumik, Driffield, Gaur, Mickiewicz and Vaaler (2019) that they help upgrade corporate governance in the respective home countries, thus shaping governance practices such as property rights and rule of law. MNEs as agents of social change would indeed be a fruitful area of research. A recent article in JIBS shows convincingly that IB research does not yet leverage the international experience of MNEs to broaden its agenda beyond firm or team performance to including equality, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) (Fitzsimmons et al., 2023). On a more positive note, the authors point to the intersection of IB and EDI research as a potentially productive opportunity to lead societal change.

Global organizations

For the “Global Organizations” circle, Goerzen et al. (2024) have listed MNEs, regulators, noncredit financial organizations (NFOs), public–private partnerships (PPPs), trade associations, and coalitions as examples, highlighting a range of organizations in addition to MNEs that play a role in global cities. They also introduce the notions that “globalization and the future of MNE management goes beyond the world of high-level managers, their massive corporations, and the skilled technocrats and their organizations” and that “globalization also includes low level administrators who answer the phone, custodians who empty the garbage, and the caregivers who watch over the kids while their top flight parents are at work…many of whom are from disadvantaged groups.”

By calling attention to a large range of staff and workers who support managers and skilled personnel, Goerzen et al. (2024) emphasize globalization and global cities as products of processes rather than a static given. It is not just high-level and skilled workers that global cities need, they also need a large number of unskilled and low-level workers. When these workers are in short supply, global cities turn to other countries. In other words, cities compete globally not only for talent, human capital, and expatriates, but all kinds of workers across the entire skill spectrum. Indeed, migration is one of the megatrends that the authors have highlighted; it is not an exaggeration to say that globalization and global cities would not exist without migration.

Wealthier economies in East and Southeast Asia, for example, use the guest-worker approach to manage migration of foreign workers. Large numbers of migrant workers from the Philippines, Indonesia, Thailand, and Sri Lanka are employed in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Singapore, where wage increases over the past decades have resulted in shortages of low-skilled labor in domestic work, restaurants, and low-end services. At the same time, many developing economies welcome the opportunity to export their excess unskilled workers, both women and men, in order to relieve unemployment pressures, generate remittances, and manage labor surpluses and their potentially disruptive political effect. In labor-exporting countries such as Mexico, El Salvador, Indonesia, the Philippines, Turkey, Morocco, Jordan, and Yemen, remittances account for a significant proportion of the national economy. In addition to augmenting household income and sustaining livelihood, remittances are also conducive to increasing capital availability and new business creation in the sending country (Vaaler, 2011). Organized recruitment by sending countries is integral to this migration system. For example, the Philippines has maintained a well-oiled and successful recruitment system, by monitoring the labor markets in destination countries, and liaising and enforcing contracts between foreign employers and Filipino workers. By doing so, the Philippines has enabled a sustained flow of remittances from migrant workers abroad, which account for 10% of the country’s gross domestic product (Akçay, 2022). In this light, global organizations also include recruitment agencies and government organizations that match employers with employees across international borders, which help shape the spatial pattern and volume of international migration. Analyzing the Philippine migration industry for migrant domestic workers, Debonneville (2021: 18) argues that recruitment agencies operate based on both “the economic logic of profit and the political moral logic of protection,” and that these two logics go hand-in-hand in order to remain competitive in the global domestic labor market.

While guest-worker programs are designed for short-term employment, in reality migrant workers may have their contracts renewed many times and end up staying in destination cities for an extended period of time. Some domestic workers in Hong Kong, who are hired when parents need caregiving support for their young children, stay as a helper in the family for decades. These workers make it possible for middle-class families to contribute to maintaining Hong Kong as a global city through their skilled and professional work. At the same time, issues of human and labor rights of these workers need to be addressed. Studies have highlighted the context of housework that has made migrant women domestic workers vulnerable to abuses, such as long working hours, lack of accommodation, incomplete rest days, deprivation of hygiene needs, nonpayment or underpayment, and even psychological and sexual abuses (Cheng, 1996; Ullah, 2015). In response, advocacy organizations and NGOs have led efforts to protect the rights, interests, and well-being of migrant workers (e.g., Amalia, 2020). Like recruitment agencies, these organizations can also be thought of as global organizations because their focus is on international migrants.

The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries constitute another popular destination of international migration. Since the late 2000s, the oil-producing GCC states have seen a rapid influx of migrant workers, and today they all have a predominant foreign population. In the late 2010s, expatriates accounted for 70% of the labor force in Saudi Arabia and 80% of the labor force in the UAE (Aarthi & Sahu, 2021). Most foreign workers are from India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan, hold private-sector jobs, and their stay is monitored by private sponsors rather than an elaborate recruitment system. However, the private sponsorship system is fraught with issues of exploitation and abuse, ranging from “confiscation of passports to severe restrictions placed on workers’ movement, nonpayment of wages, strenuous work, and unsafe conditions” (Aarthi & Sahu, 2021: 420), leading to pressure from international organizations like ILO and Human Rights Watch on the GCC states to reform their labor migration policies. These organizations are therefore part of the megatrends that define globalization in the present day. Barnard, Deeds, Mudambi and Vaaler (2019) have highlighted “a new kind of organization dedicated specifically to serving migrant communities abroad and coordinating their activities in support of economic, political, and social development back home.” They point out that IB executives ought to consider how investment projects affect the livelihoods of host-country citizens at home and abroad. In other words, MNEs are also influenced by organizations working on behalf of migrants that are also multinational in their mission and activities.

The discussion of globalization and global organizations by Goerzen et al. (2024) seeks to be inclusive and goes far beyond MNEs whose primary focus is economic performance. It also recognizes megatrends such as migration that shape global cities. In this light, global organizations that are relevant to research on global cities and IB should include not only those directly related to LOF in a traditional sense, i.e., costs of doing business, but also those that help shape global flows of people and their rights and well-being. To be sure, MNEs are not independent of the observed megatrends. Some of these megatrends have created new opportunities, such as MNEs recruiting and training migrants and refugees in their attempt to compete for global labor (Barnard et al., 2019).

Global locations

While the findings in Goerzen et al. (2013) may still hold true 10 years later, the focus of their retrospective (Goerzen et al., 2024) appears to be beyond which economic activities are within and which are outside the physical boundaries of global cities. Rather, they commented on what happens in cities and what cities represent. This perspective situates global cities in the context of globalization and as “a subject and not the object of inquiry” (Goerzen et al., 2024). They quote German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, that “cities are the place where ideas, concepts and solutions are made.” They also suggest that space and place be viewed as a subject and not the object of inquiry, that one should consider “alternative contexts of space and place” that are “subject to forces that yield vastly different realities,” and that “this goes to the heart of the notion of ‘othering’ discussed by Beugelsdijk (2022).”

This new line of thinking can be unpacked into two themes: alternative units of analysis; and alternative contexts of space and place. Both have been the foci of geographers’ approach toward global cities and of recent research on urbanization. The research on global city-regions, for example, expands the unit of analysis from a city to including the region within which the city is situated. Scott, Agnew, Soja and Storper (2001:11) argue for thinking about “how city-regions increasingly function as essential spatial nodes of the global economy and as distinctive political actors on the world stage.” Beyond just the economic, they advocate for a concept also in political, territorial, and social terms, and as such conclude that “the city in the narrow sense is less an appropriate or viable unit of local social organization than city-regions or regional networks of cities” (p. 11). They also observe that “[w]hereas most metropolitan regions in the past were focused mainly on one or perhaps two clearly defined central cities, the city-regions of today are becoming increasingly polycentric or multiclustered agglomerations” (p. 18), citing the Pearl River Delta as an example. A “super mega city-region” in southern China, Pearl River Delta consists of the anchor cities of Guangzhou and Shenzhen, each with population above 10 million, and seven other cities in the Guangdong province, all “consolidated into a cluster of urban settlements that [are] connected by dense flows of people and information” (Yeh & Chen, 2020: 640). The more recent blueprint by China’s central government to extend the Pearl River Delta to including Hong Kong and Macau, forming the Greater Bay Area, further boosts this polycentric city-region’s population to over 70 million and aims at accelerating connectivity such as transportation and information infrastructure (Li et al., 2022). In a recent article, Scott (2022: 116) points out that “city-regions are widely distributed across all five continents.” Data from 1955 to 2015 show that “More and more of the world’s population is accommodated in cities of all sizes, but an increasingly large proportion of the total urbanized population is contained in the very biggest centers” (p. 116). As for city-regions and MNEs, Lorenzen et al. (2020) suggest that the predominant location of MNEs in core cities may exacerbate the catchment area’s decline, because the international connectedness that these enterprises create may adversely affect local connectedness. Yet, they caution that the concept of city-regions has not yet received much attention in IB research and that this limits the advance of MNE theory.

Geographers’ shifting their unit of analysis from global cities to global city-regions reflects also how context is key to their understanding of place. Scott (2022: 116) highlights a “recent decisive shift in patterns of urban growth from Europe and North America to other parts of the world, and above all to Asia and Africa.” According to Agnew (1987: 43), “Place is defined as the geographical context or locality in which agency interpellates social structure.” As a political geographer, he focuses on political behavior: “Consequently, political behaviour is viewed as the product of agency as structured by the historically constituted social contexts in which people live their lives – in a word, places” (p. 43). In other words, it is people who define the context, and therefore, the place. Human geographers have long written about “sense of place,” which Zaheer and Nachum (2011: 99) describe as “an individual or group’s interpretations of and relationships with a place, which infuses a particular location with distinct meaning and value.” They further argue that for a location to become a source of value for an MNE, a deep sense of place is essential in order for the firm to recognize, transform and incorporate location resources. One way in which to develop sense of place is through engagement with local customers and suppliers. In other words, the value of a location is not the same for all firms.

Recent research articulates alternative contexts even more explicitly by focusing empirically on regions of the world that were previously only peripheral to, if at all included, in research on global cities. Robinson and Roy (2016) criticize urban theory for focusing heavily on the North Atlantic and for neglecting the diversity and shifting geographies of global urbanization. Instead, Robinson (2016: 187) advocates “building theory from different contexts,” a comparative approach “which can help to develop new understandings of the expanding and diverse world of cities and urbanization processes.” In the edited book New Global Cities in Latin America and Asia: Welcome to the Twenty-First Century, Pablo Baisotti (2022: 3) observes that “… the overwhelming majority of cities in Latin America and Asia have global characteristics, although they were not initially established as economic and financial nodes, unlike those of the First World.” Similarly, research on MNEs’ location choice has tended to focus on firms from developed economies. At the same time, Li et al. (2018) observe that 30% of the Fortune Global 500 firms are from emerging economies and that in 2015 40% of industry leaders were firms from emerging markets. Their research suggests that the “idiosyncrasies of the environments from which MNEs originate leave a stamp on their subsequent international behaviour” (p. 1099). For example, Taiwan-based MNEs tend to favor China for R&D activities due to geographical and linguistic proximity, factors that do not appear as important for MNEs from developed economies.

Chubarov and Brooker (2013) argue that despite the rapid growth of the Chinese economy since the 1980s and the emergence of a number of large cities that draw in capital, labor and multinational firms and characterized by their competing claims of becoming global cities, research on global cities has tended to focus on case studies from the Global North. Taking the point about China’s rapid globalization and urbanization further, Smart and Curran’s (2023) chapter in the edited volume, China Urbanizing: Impacts and Transitions, showcases “smart urbanism” as indicative of new roads of urbanization created by China that are to be followed by other countries. The volume’s editors, Wu and Gao (2023: 4), further elaborate on the concept of provincialization: “to provincialize is to decenter perspectives that have allowed theories situated in the context of a particular world region (Europe/North America) to be seen as universal.” Focusing more broadly on Asia, Yeung, and Lin (2003) have long called for new and broader theories of economic geography that can better theorize dynamic economic changes and geographic processes that are observed in regions beyond the Anglo-American context. They highlight the notion of economic geographies of Asia “theorizing back” (p. 121), built on theoretical insights drawn from research on Asia such as the developmental state, social capital, and transnationalism, among others.

Other geographers, urban planners and researchers have also called for decentering research on urbanization and cities. For example, in China’s Urban Space: Development under Market Socialism (McGee et al., 2007) have made a powerful case that the Chinese experience can help revise assumptions of urbanization, by illustrating that urbanization involves multiple tracks rather than a linear progression from the urban core, and that processes such as rescaling and repositioning of urban and rural areas are as important as, if not more important than, the form of urbanization. In the article “China’s landed urbanization: State power reshuffling, land commodification, and municipal finance in the growth of metropolises,” Lin (2014) calls for theories of planetary urbanization to seriously and fully embrace the Global South. Also focusing on China, Smith (2022: 1558) concludes that the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is “first and foremost, a network of cities connected through global infrastructure.” Wang, Mirsardin, Sun and Yang (2021) show that the BRI is part of China’s integration with global production networks and has enhanced the internationalization of China’s MNEs. Wu (2020: 180) highlights the processes of emerging urbanism. He observes that China provides a useful perspective to understand the emergence of cities, because despite the prominence of state-led or policy-driven urbanization initiatives, “the development is not fully planned but rather contingent upon agencies and histories.” He argues that local institutions and structures, such as those that govern household registration (hukou) and land, are indispensable factors. For example, although hukou has been considered a barrier to urban settlement of rural migrants, many Chinese cities – except the very large ones – have relaxed hukou restrictions in order to attract migrants to stay, while at the same time rural migrants may desire to hold on to their rural hukou because they are reluctant to give up access to farmland and social ties to rural communities (Chen & Fan, 2016; Tan, 2023). In other words, decisions that ultimately govern urban development are often contingent upon local variants of policies, both urban and rural.

Interestingly, the Decade Award paper starts with the question of locational choice, but Goerzen et al. (2024) highlights alternative units of analysis and place. In other words, the geography of locational choice has become more fluid, both in terms of physical boundaries and world regions. While nation states continue to be major units of analysis, it is important to also pay attention to intra-national variations (Tung, 2008; Tung & Stahl, 2018). The U.S. Department of State, for example, has created a new position of Special Representative for City and State Diplomacy in 2022, signifying the importance of subnational units and variations in public diplomacy. Within nations, global cities constitute key locational choices for MNEs, but at the same time the boundaries that matter may not be where a city begins and where it ends. Global cities are highly varied, contextualized, and imbedded in regions. They are also found across the world. These empirical observations are more than sufficient to generate much more attention on research on global cities and IB, in order to fill the gaps that have been identified. As Tung (2023: 7) emphasizes in her editorial, “it is imperative that JIBS progress beyond its Western-centric phase to a more inclusive and global view of intellectual rigor and excellence.”

Conclusion

Goerzen et al.’s (2024) “Global Cities: Retrospective and a Look Forward” is not only a response to changes since the publication of their 2013 Decade Award paper, but also a good example of generative research. This commentary is a product of this process of generativity, as it has attempted to respond to and expand the authors’ proposed framework for the future of IB research, marked by the three overlapping circles of global issues, global organizations, and global locations, all placing research on global cities and IB in the evolving and alternative contexts of globalization.

The literature of economic geography, urban studies, political economy, and allied fields can contribute to IB research in significant ways, and Goerzen et al. (2024) not only acknowledge that but also engage with the fundamental tenets of these subfields. In this commentary, I have highlighted a few observations and recent research from these subfields related to global issues, global organizations, and global locations. I have argued that global cities are both sites of and leaders to address global issues, rightly identified by Goerzen et al. (2024) to include social justice, human rights, environmental stewardship, individual well-being, and digitalization. For global organizations, I have drawn attention to international migrant workers who make it possible for citizens of destination cities to engage in work and activities that enable their cities to be global cities. Organizations that facilitate migrant workers’ recruitment may not resemble MNEs in their traditional sense, but they do conduct multinational business involving all aspects of the migration industry in multiple locations, marketing migrant workers, matching employees with employers, providing job training to workers, and much more, and are important drivers of globalization (Debonneville, 2021). Finally, I have referenced in particular geographers’ research to broaden the discussion of global locations, by highlighting global city-regions and alternative contexts beyond the Global North, contexts that have traditionally been peripheralized in globalization, global cities and urbanization research but are key to the future of pertinent theories.

While this commentary has not focused specifically on LOF, a cornerstone of the 2013 paper, it may be worth noting that the concept of “foreignness” is also a function of evolving and alternative contexts. The 2013 paper couched LOF in relation to the costs of doing business abroad, broken down into uncertainty, discrimination, and complexity. While this perspective continues to be useful for IB research, the geopolitical realities of the 2020s complicate the relationship between foreignness and being abroad. As an example, while Asian Americans have always struggled to be fully accepted as Americans, U.S.–China tensions since the Trump administration and since the pandemic have certainly exacerbated their sense of vulnerability in the U.S. Do Asian Americans have to address LOF without even going abroad?

If the 2013 paper has proved to be influential in both quantitative and qualitative terms, then the authors’ generative ability for IB and related research provides further support for their well-deserved Decade Award. Congratulations!

References

Aarthi, S. V., & Sahu, M. (2021). Migration policy in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states: A critical analysis. Contemporary Review of the Middle East, 8(4), 410–434.

Agnew, J. A. (1987). Place and politics: The geographical mediation of state and society. Allen and Unwin.

Akçay, S. (2022). Remittances and income inequality in the Philippines. Asian-Pacific Economic Literature, 36(1), 30–47.

Amalia, E. (2020). Sustaining transnational activism between Indonesia and Hong Kong. Asian and Pacific Migration Journal, 29(1), 12–29.

Baisotti, P. (Ed.). (2022). New global cities in Latin America and Asia: Welcome to the twenty-first century. University of Michigan Press.

Barnard, H., Deeds, D., Mudambi, R., & Vaaler, P. M. (2019). Migrants, migration policies, and international business research: Current trends and new directions. Journal of International Business Policy, 2(4), 275–288.

Beugelsdijk, S. (2022). Capitalizing on the uniqueness of international business: Towards a theory of place, space, and organization. Journal of International Business Studies, 53(9), 2050–2067.

Bhaumik, S., Driffield, N., Gaur, A., Mickiewicz, T., & Vaaler, P. (2019). Corporate governance and MNE strategies in emerging economies. Journal of World Business, 54(4), 234–243.

Chen, C., & Fan, C. C. (2016). China’s hukou puzzle: Why don’t rural migrants want urban hukou? China Review, 16(3), 9–39.

Cheng, S.-J.A. (1996). Migrant women domestic workers in Hong Kong, Singapore and Taiwan: A comparative analysis. Asian and Pacific Migration Journal, 5(1), 139–152.

Chubarov, I., & Brooker, D. (2013). Multiple pathways to global city formation: A functional approach and review of recent evidence in China. Cities, 35, 181–189.

Debonneville, J. (2021). An organizational approach to the Philippine migration industry: Recruiting, matching and tailoring migrant domestic workers. Comparative Migration Studies, 9(1), 12.

Dougherty, C., and E. Goldberg. (2022). What comes next for the most empty downtown in America. In New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/17/business/economy/california-san-francisco-empty-downtown.html.

Fitzsimmons, S., Özbilgin, M. F., Thomas, D. C., & Nkomo, S. (2023). Equality, diversity, and inclusion in international business: A review and research agenda. Journal of International Business Studies, 54(8), 1402–1422.

Florida, R. (2017). The new urban crisis: How our cities are increasing inequality, deepening segregation, and failing the middle class-and what we can do about it. Basic Books.

Florida, R., Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Storper, M. (2023). Critical commentary: Cities in a post-COVID world. Urban Studies, 60(8), 1509–1531.

Goerzen, A., Asmussen, C. G., & Nielsen, B. B. (2024). Global cities, the liability of foreignness, and theory on place and space in international business. Journal of International Business Studies (forthcoming).

Goerzen, A., Asmussen, C. G., & Nielsen, B. B. (2013). Global cities and multinational enterprise location strategy. Journal of International Business Studies, 44(5), 427–450.

Hamidi, S., Sabouri, S., & Ewing, R. (2020). Does density aggravate the COVID-19 pandemic? Journal of the American Planning Association, 86(4), 495–509.

Harter, C., & Scauzillo, S. (2023). LA is losing the battle against mental illness among its homeless. In Los Angeles Daily News. https://www.dailynews.com/2023/01/28/los-angeles-is-losing-the-battle-against-mental-illness-among-its-homeless/.

Kwok, C. C. Y., & Tadesse, S. (2006). The MNC as an agent of change for host-country institutions: FDI and corruption. Journal of International Business Studies, 37(6), 767–785.

Lai, S.-K., & Huang, J.-Y. (2022). Why large cities are more vulnerable to the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Urban Management, 11(1), 1–5.

Li, C., Ng, M. K., Tang, Y., & Fung, T. (2022). From a ‘world factory’ to China’s Bay Area: A review of the outline of the development plan for the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area. Planning Theory & Practice, 23(2), 310–314.

Li, X., Quan, R., Stoian, M.-C., & Azar, G. (2018). Do MNEs from developed and emerging economies differ in their location choice of FDI? A 36-year review. International Business Review, 27(5), 1089–1103.

Lin, G. C. S. (2014). China’s landed urbanization: State power reshuffling, land commodification, and municipal finance in the growth of metropolises. Environment and Planning a: Economy and Space, 46(8), 1814–1835.

Lorenzen, M., Mudambi, R., & Schotter, A. (2020). International connectedness and local disconnectedness: MNE strategy, city-regions and disruption. Journal of International Business Studies, 51(8), 1199–1222.

McGee, T. G., Lin, G. C. S., Marton, A. M., Wang, M. Y. L., & Wu, J. P. (2007). China’s urban space: Development under market socialism. Routledge.

Mitchell, M. C. (2010). An institutional perspective of the MNC as a social change agent: the case of environmentalism. Journal of Global Responsibility, 1(2), 382–398.

Robinson, J. (2016). Comparative urbanism: New geographies and cultures of theorizing the urban. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 40(1), 187–199.

Robinson, J., & Roy, A. (2016). Debate on global urbanisms and the nature of urban theory. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 40(1), 181–186.

Scott, A. J. (2022). City-regions reconsidered. In P. Baisotti (Ed.), New global cities in Latin America and Asia: Welcome to the twenty-first century (pp. 114–149). University of Michigan Press.

Scott, A. J., Agnew, J., Soja, E. W., & Storper, M. (2001). Global city-regions. In A. J. Scott (Ed.), Global city regions: Trends, theory, policy (pp. 11–32). Oxford University Press.

Smart, A., & Curran, D. (2023). Prospects and social impact of big data-driven urban governance in China: Provincializing smart city research. In W. Wu & Q. Gao (Eds.), China urbanizing: Impacts and transitions (pp. 205–227). University of Pennsylvania Press.

Smith, N. R. (2022). Continental metropolitanization: Chongqing and the urban origins of China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Urban Geography, 43(10), 1544–1564.

Tan, K. C. (2023). China eases residential registration rules to boost growth. In Nikkei Asia. https://asia.nikkei.com/Economy/China-eases-residential-registration-rules-to-boost-growth

Tessema, M. T., Tesform, G., Faircloth, M. A., Tesfagiorgis, M., & Teckle, P. (2022). The “great resignation”: Causes, consequences, and creative HR management strategies. Journal of Human Resource and Sustainability Studies, 10, 161–178.

Tung, R. L. (2008). The cross-cultural research imperative: the need to balance cross-national and intra-national diversity. Journal of International Business Studies, 39(1), 41–46.

Tung, R. L. (2023). To make JIBS matter for a better world. Journal of International Business Studies, 54(1), 1–10.

Tung, R. L., & Stahl, G. K. (2018). The tortuous evolution of the role of culture in IB research: What we know, what we don’t know, and where we are headed. Journal of International Business Studies, 49(9), 1167–1189.

Ullah, A. A. (2015). Abuse and violence against foreign domestic workers: A case from Hong Kong. Regioninės Studijos, 2, 221–238.

Vaaler, P. M. (2011). Immigrant remittances and the venture investment environment of developing countries. Journal of International Business Studies, 42(9), 1121–1149.

Wang, J., Mirsardin, I., Sun, Y., & Yang, X. (2021). The internationalization of Chinese multinational enterprises under the Belt-and-Road Initiative. Strategic Change, 30(6), 509–515.

Wu, F. (2020). Emerging cities and urban theories: A Chinese perspective. In D. Pumain (Ed.), Theories and models of urbanization: geography, economics and computing sciences (pp. 171–182). Springer.

Wu, W., & Gao, Q. (Eds.). (2023). China urbanizing: Impacts and transitions. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Yeh, A.G.-O., & Chen, Z. (2020). From cities to super mega city regions in China in a new wave of urbanisation and economic transition: Issues and challenges. Urban Studies, 57(3), 636–654.

Yeung, H. W. (2009). Transnational corporations, global production networks, and urban and regional development: A geographer’s perspective on multinational enterprises and the global economy. Growth and Change, 40(2), 197–226.

Yeung, H. W., & Lin, G. C. S. (2003). Theorizing economic geographies of Asia. Economic Geography, 79(2), 107–128.

Zaheer, S., & Nachum, L. (2011). Sense of place: From location resources to MNE locational capital. Global Strategy Journal, 1(1–2), 96–108.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the UCLA Chancellor’s Office for financial support for the research; Anthony Goerzen, Christian Geisler Asmussen and Bo Bernhard Nielsen for their 2013 and 2024 papers; Kaz Asakawa and Jeremy Clegg for their insights; Rosalie Tung for her leadership and vision; and two anonymous referees for their comments and suggestions that helped improve the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Accepted by Rosalie L. Tung, Editor-in-Chief, 27 October 2023. This article has been with the author for one revision and was single-blind reviewed.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fan, C.C. Globalizing research on global cities and international business. J Int Bus Stud 55, 28–36 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-023-00670-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-023-00670-7