Abstract

Cancer registries encompass a broad array of functions that underpin cancer control efforts. Despite education being fundamental to improving patient outcomes, little is known regarding the educational value of cancer registries. This review will evaluate the educational value of cancer registries for key stakeholders as reported within published literature and identify opportunities for enhancing their educational value. Four databases (Ovid Medline, Embase, CINAHL and Web of Science) were searched using a predefined search strategy in keeping with the PRISMA statement. Data was extracted and synthesised in narrative format. Themes and frequency of discussion of educational content were explored using thematic content analysis. From 952 titles, ten eligible studies were identified, highlighting six stakeholder groups. Educational outcomes were identified relating to clinicians (6/10), researchers (5/10), patients (4/10), public health organisations (3/10), medical students (1/10) and the public (1/10). Cancer registries were found to educationally benefit key stakeholders despite educational value not being a key focus of any study. Deliberate efforts to harness the educational value of cancer registries should be considered to enable data-driven quality improvement, with the vast amount of data promising ample educational benefit.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the global burden of cancer predicted to continue growing at a rapid rate [1], cancer registries have increasingly become recognised as essential tools that underpin effective cancer care [2]. Cancer registries are information systems designed for the collection, storage, management and analysis of data relating to patients diagnosed with cancer [3]. Since their establishment in the early 1900s, advancements in data management and medical technology have spurred the continued evolution of cancer registries, expanding their scope of application far beyond their early conceptualisation as ‘back room’ databases for cancer quantification [4]. Beyond providing comprehensive epidemiological surveillance, cancer registries also generate research that informs the development of cancer control strategies adopted by hospitals, non-governmental and governmental health institutions [5].

The function of cancer registries does vary depending on the type of registry. Hospital-based registries focus on improving patient care at that specific service, whilst population-based registries generate more broadly applicable conclusions for a defined geographical population [6]. Cancer registries also extend transnationally to investigate international patterns of prevalence and survival discrepancies, with the aim of informing the development of health policy to reduce global cancer inequalities [7]. The steady increase in cancer registries highlights their increasing recognition as an indispensable component of successful local, national and international cancer control efforts [8].

Despite their steady proliferation, cancer registries face challenges. Data quality is a fundamental determinant of the reliability of registry data output and significant effort has been directed towards developing methods for assessing data comparability, validity, timeliness and completeness as parameters of data quality [9, 10]. Confidentiality also poses a challenge in balancing respect for the data privacy against data accessibility and public health benefit, and efforts to reconcile ethical considerations are ongoing [11, 12]. The extent to which registry data entry should be legally mandated is also a point of contention. In Australia, mandatory reporting applies only to the screening, diagnosis and mortality of particular cancers [13]. However, comprehensive data on staging at the time of diagnosis, treatment and recurrence is needed across all cancers [14]. To build a representative evidence base, a wider scope of geographic coverage by registries logically seems superior; however, whether this additional coverage conveys sufficient benefit to justify the additional resources required remains unclear [15]. Evidence-based recommendations regarding optimal registry design and establishment are also lacking [16], reflecting the independent, organic and often haphazard process of cancer registry proliferation [17]. Detailed exploration of these issues is beyond the scope of this study, yet they demonstrate some of the nuances within cancer registries that are important to elucidate in reaching a considered and holistic perspective to strengthen educational outcomes.

Although published literature is an area where cancer registries have been studied extensively, currently, there is limited research specifically characterising their educational value. Assessing the educational value of cancer registries is critical, as education is fundamental in driving registry-derived decision-making and hence maximising the value of cancer registries.

The overall aims and objectives of this study were as follows:

-

1.

To outline the characteristics of cancer registries in surgical oncology

-

2.

To describe the educational value of surgical cancer registries for clinicians, trainees, patients, researchers, public health organisations, medical students and the public as reported within published literature

-

3.

To describe potential strategies to improve the educational value of cancer registries

Methods

The systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [18]. Local institutional ethical approval was not sought as all included data was obtained from previously published studies. This study was prospectively registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO: CRD42022334752).

Search Strategy and Eligibility

A formal systematic search was conducted in the Ovid Medline (1946 – 17 June 2022), Embase (1947 – 17 June 2022), CINAHL (1937 – 20 June 2022) and Web of Science (1900 – 20 June 2022) databases to identify relevant titles. The screening of studies was performed by two independent reviewers (JL and HT) using a predetermined search strategy designed by senior authors (see supplementary appendix 1). Manual cross-referencing of reference lists from previously included articles and included trials was also undertaken. Manual removal of duplicate studies was performed before all titles were screened. Retrieved studies were reviewed to ensure inclusion criteria were met for the primary outcome at a minimum, with discordances in opinion resolved through open consultation with a third author (HM).

Inclusion criteria:

-

1.

Studies focusing on cancer registries as the primary intervention

-

2.

Explicit discussion of educational value that facilitates learning, improved decision-making, or quality improvement for the key stakeholders as an outcome where educational value is defined as any registry-based intervention that facilitates learning, decision making or quality improvement.

Exclusion criteria:

-

1.

Studies assessing cancer registries that did not detail an educational perspective

-

2.

Studies not published in the English language

-

3.

Conference abstracts and proceedings

-

4.

Studies without full-text manuscripts

Data Extraction

Data extraction was also performed by two independent reviewers (JL and HT). Information relating to baseline study characteristics, cancer registry characteristics and educational outcomes was extracted. Baseline study characteristics included author, year, journal, country, study period, study design and article perspective. Cancer registry characteristics included registry name, governing organisation, location, date of establishment, registry type, patient group or focus group, registry inclusion and exclusion criteria, study sample size and the overall registry purpose.

Methodological Quality

The quality of included studies was assessed using the Medical Education Research Quality Index (MERSQI) [19, 20] and is included in supplementary appendix 2. The critical appraisal was completed by two reviewers independently (JL and HT), and a third reviewer (HM) was asked to arbitrate in cases of discrepancies in opinion.

Qualitative Content Analysis

To reveal educational themes discussed by the authors of the included studies, textual thematic analysis was performed on the discussion sections of the publications. Thematic analysis was performed following the principles of Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six-step process of thematic analysis [21]. Using NVIVO 12 (QSR International, Burlington, MA), the text was auto-coded to explore themes. These themes were then used as a reference for an iterative review of the full text to complete thematic coding. Themes were then refined and analysed to identify the content and frequency of themes.

Results

Study Selection

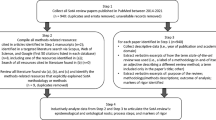

The systematic search strategy identified a total of 946 studies, of which 91 duplicate studies were manually removed. The remaining 855 studies were screened for relevance against titles and abstracts, leaving 24 studies for which full-text reports were sought. Full-text reports were retrieved for 16 studies before 8 studies were excluded: incorrect outcome (n = 4), non-English (n = 3) and not utilizing cancer registry as an intervention (n = 1). Citation searching yielded 6 further studies, and after 6 full-text reports were assessed for eligibility, 2 were included. Overall, 10 studies fulfilled our inclusion criteria and are presented in this systematic review (Fig. 1). Due to heterogeneity in the study method and result, findings are presented as narrative synthesis and meta-analysis was not appropriate.

Study Characteristics

The characteristics of the included studies have been summarised in Table 1. The studies were all published between 1989 and 2022. Publications came from four countries — USA [22,23,24,25,26], Australia [27,28,29], Canada [30] and the UK [17]. Five studies were observational [23,24,25,26, 28], whilst the remaining five studies were narrative reviews [17, 22, 27, 29, 30]. Six studies were written from a clinician perspective [22,23,24,25, 28, 29], two from a population health perspective [17, 27], one from a nursing perspective [26], and one from a genetic counsellor’s perspective [30].

Methodological Quality

In accordance with the Medical Education Research Quality Index (MERSQI) [19, 20], the methodological quality of the included papers has been tabulated in Appendix 2. The average MERSQI score across the studies was 9.7, suggesting overall low methodological quality. All studies dealt with outcomes such as satisfaction, attitudes, perceptions, opinions, and general facts, and all but four studies [17, 23, 24, 28] generated data that was an assessment by study participants, rather than objective data.

Cancer Registry Characteristics

The characteristics of the cancer registries are presented in Table 2. The establishment dates of the cancer registries ranged from 1980 to 2011. Four papers referenced a single specific cancer registry [22,23,24, 26], two referenced multiple specific registries [28, 30] and four involved general discussion without focusing on any specific registry [17, 25, 27, 29]. Of the papers discussing specific registries, one registry was based at a single institution [23], three spanned multiple institutions [22, 28, 30], one was state-based [24] and one was nationally-based [26]. Three studies referenced registries focusing only on a single cancer type [22, 24, 28], and three studies referenced registries that included multiple cancer types [23, 25, 29]. Patient sample sizes ranged from 30 to 12,341.

Educational Outcomes

Educational outcomes are presented in supplementary appendix 3. There were six key stakeholder groups for which educational outcomes were identified — clinicians, medical students, patients, researchers, public health organisations and the public. Clinicians were the most frequently referenced group to derive educational value from registries, reported in six studies [22, 23, 25, 26, 29, 30]. Five studies referenced education for researchers [17, 22, 23, 28, 29], four studies referenced patient education [23, 24, 29, 30], three studies referenced education for public health organisations [27, 29, 30], one study referenced medical students’ education [25] and one study referenced educating the public [27].

Clinicians

Cancer registries conferred educational benefit for clinicians relating to continuing medical education and quality improvement. Chen et al. [23] demonstrated that registry-derived clinical benchmarks promote data-driven quality assurance in radiation oncology via documentation of adherence to specific best-practice treatment pathways. Jiagge et al. [22] demonstrated that an international registry facilitated the creation of a reciprocal educational exchange program between institutions, which included training in biopsy and immunohistochemistry techniques. Joishy et al. [25] highlighted how registries can facilitate clinical benchmarking, allowing clinicians to compare their own data with national and international standards to identify areas for improvement. Rothenmund et al. [30] found that hereditary colorectal cancer registries could be used to develop standardised surveillance protocols, providing a foundation for quality control and ongoing evaluation of service results.

Researchers

There were no studies that directly demonstrated educational value for researchers. However, there was evidence that registries provided a repository of data that could catalyse research output whilst reducing resource burden. This in turn could lead to educational benefits by providing a platform for education in registry research. Chen et al. [23] found that the development of their radiation-oncology-specific registry supported 54 independent, investigator-initiated research studies, of which 50 were presented as abstracts at scientific meetings, and 23 were published in peer-reviewed journals. MacCallum et al. [28] found that although multi-institutional clinical colorectal cancer registries generated a significant body of outcomes research that could positively affect value, efficiency, effectiveness and resource allocation in cancer management, the output was low in proportion to the size of the data sets and the resources required to maintain them.

Patients

Cancer registries conferred educational value for patients by harnessing data to develop educational materials. Auffenberg et al. [24] found that a web-based platform developed from a registry for men with localised prostate cancer generated individualised and evidence-based prostate cancer treatment predictions based on demographic and clinicopathologic features, which complemented existing medical consultation to reduce decisional uncertainty. Rothenmund et al. [30] found that hereditary colorectal cancer registries provided direct education to patients and at-risk relatives and functioned as a platform for streamlined contact of patients for research involvement to further propagate educational outcomes.

Public Health Organisations

For public health organisations, cancer registries provide data and research that informs short- and long-term policy development, as well as optimal resource allocation. Parkin et al. [17] found that population-based cancer registry data enables an appraisal of current cancer burden and cancer control, which provides a framework for action and target-setting. For example, cancer registry data was used to assess the link between lung cancer and smoking, facilitating the development of targeted and evidence-based anti-smoking campaigns aimed at providing health education to effect behavioural change.

Medical Students

Joishy et al. [25] found that exposure to cancer registries during clinical rotations and medical student participation in data entry may enhance knowledge of cancer-related signs and symptoms, whilst also reinforcing the value of accuracy in data entry. Exposure to the scientific nature of information-gathering required for registries also represented a valuable and transferrable skill for medical students.

Public

Burton et al. [27] demonstrated that research derived from registry data can contribute to the development of public health campaigns and thus preventative health education for the public.

Thematic Analysis

Thematic content analysis of the author’s discussion of each publication did not feature a discussion of educational interventions as a major theme. Major themes were data, patient-based application of cancer registry data, clinical applications of cancer registries and research. Secondary themes of discussion related to physician involvement in cancer registries, registry/database structure and quality improvement efforts. Within-text analysis of ‘education’ showed 8 results, with the key emphasis on patient self-education based on registry information. Synonym searching did not reveal additional themes relating to educational value or the development of educational interventions.

Discussion

This review of published literature has identified that cancer registries have potential educational value for many associated stakeholders, especially clinicians, researchers, patients, and public health organisations. However, explicit utilisation of a cancer registry for educational purposes is rare. Educational value is defined in this study as the use of registry data to improve knowledge across these key stakeholder groups. Frameworks for understanding educational value feature throughout educational literature, with Kirkpatrick’s level of evidence model as one example [31]. In this framework educational value of an intervention is assessed by its impact on attitudes, knowledge, skills, behaviour, practices or patient outcomes. This outcome-centred approach to assessing educational value is practically applicable as it highlights the tangible, assessable aspects of cancer registry impact.

Kirkpatrick’s framework can provide insight into the potential educational value of cancer registries across key stakeholder groups. Through synthesising the overall impact into categories based on this hierarchy, both the scope of the educational value and the avenues for the development of strategies to improve the educational value of cancer registries have been considered, summarised in supplementary appendix 4.

Educational activities that may be of value also differ across the key stakeholder groups. For clinicians, cancer registries facilitated a variety of educational benefits relating to continuing medical education. One recurring theme was that registry data can enhance clinician decision-making and effect tangible improvements in clinical practice, via the provision of best-practice research updates that encourage self-education. Registries also provide clinicians with comparative data, either against predetermined standards in the form of auditing or against other institutions in the form of clinical benchmarking. These comparisons promote data-driven quality assurance and accountability, whereby exploration of discrepancies in clinical outcomes can provide valuable education on clinical best practices.

For researchers, the educational benefits of cancer registries lay largely in streamlining multiple aspects of research, including study generation, patient recruitment, data collection, and collaboration between institutions. Registries were demonstrated to function as a rich repository of data capable of accelerating research efficiency and output. For patients, cancer registries provided direct educational material, facilitated access to research and clinical trial opportunities and provided rapid communication of updated treatment guidelines, ultimately empowering patients to be more involved in their own clinical decision-making. For public health organisations, registries provided a framework of data to guide policy development and optimise resource allocation. These findings were consistent with recent paradigm shifts reflecting the increasingly broad array of functions that cancer registries can fulfil.

The educational value in the context of cancer registries is important to consider as it can strengthen the outcomes already supported by registry data. The primary purpose of a cancer registry is to provide a data-driven source of information to improve patient outcomes. As highlighted using the example of outcome-based assessment of educational value through Kirkpatrick’s model, this can also be achieved through education. Despite this, education is currently not a priority use of registry data based on thematic analysis. While it is not a major theme, however the major themes presented by the authors of the publications included in this review can all be applied as an educational concept indirectly. This indicates the implicit educational feature of cancer registries rather than the explicit use of the data for educational purposes. This may in part be due to the challenges in assessing educational value, with greater emphasis placed on tangible data-driven outcomes, rather than the at times intangible educational outcomes. It is important to start to address this to fully harness the educational capabilities of cancer registries.

There were several limitations of our review including the small number of relevant studies and the heterogeneity of their study designs, which precluded meta-analysis. Given this heterogeneity, there is a range of external factors that could potentially bias the results of this review. This includes faculty recruitment, infrastructure investment and changes in workplace culture and methodological limitations of the included studies. All studies were published in high-income countries; hence, findings may not be generalizable nor representative of different sociocultural contexts where cancer registries may not be as established or resourced. Lastly, but importantly, the scope of this study only explored the educational value of cancer registries as found within published literature. Thus, a more comprehensive evaluation would necessitate consideration of other grey literature sources, such as annual reports or other documentation released by cancer registry organisations. These avenues represent promising future directions for further studies to better characterise educational value beyond what is found in the literature.

Ultimately, for current cancer registries, educational outcomes are often viewed as more of a coincidental but welcomed by-product, rather than a core objective. In the pursuit of improvement, education and learning hold a core role. If cancer registries are to maximise improvement, a deliberate and intentional focus on harnessing their educational value is paramount. Examining cancer registries through an educational lens permits a clearer focus on learning and continual improvement amongst all who interact with the registry, with the vast amount of data promising ample educational benefit.

References

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A et al (2021) Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 71(3):209–249

White MC, Babcock F, Hayes NS, Mariotto AB, Wong FL, Kohler BA, Weir HK (2017) The history and use of cancer registry data by public health cancer control programs in the United States. Cancer 123(Suppl 24):4969–4976. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30905

What is a Cancer Registry?: National Cancer Institute. https://seer.cancer.gov/registries/cancer_registry/index.html. Accessed 3 Jul 2022

Armstrong BK (1992) The role of the cancer registry in cancer control. Cancer Causes Control 3(6):569–579

Platz EA (2017) Reducing cancer burden in the population: an overview of epidemiologic evidence to support policies, systems, and environmental changes. Epidemiol Rev 39(1):1–10

Pop B, Fetica B, Blaga ML, Trifa AP, Achimas-Cadariu P, Vlad CI et al (2019) The role of medical registries, potential applications and limitations. Med Pharm Rep 92(1):7–14

Coleman MP, Forman D, Bryant H, Butler J, Rachet B, Maringe C et al (2011) Cancer survival in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and the UK, 1995-2007 (the International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership): an analysis of population-based cancer registry data. Lancet 377(9760):127–138

Das A (2009) Cancer registry databases: an overview of techniques of statistical analysis and impact on cancer epidemiology. Methods Mol Biol 471:31–49

Parkin DM, Bray F (2009) Evaluation of data quality in the cancer registry: principles and methods Part II. Completeness. Eur J Cancer 45(5):756–764

Bray F, Parkin DM (2009) Evaluation of data quality in the cancer registry: principles and methods. Part I: comparability, validity and timeliness. Eur J Cancer 45(5):747–755

McLaughlin RH, Clarke CA, Crawley LM, Glaser SL (2010) Are cancer registries unconstitutional? Soc Sci Med 70(9):1295–1300

Ingelfinger JR, Drazen JM (2004) Registry research and medical privacy. N Engl J Med 350(14):1452–1453

State Government of Victoria (2014) Improving Cancer Outcomes Act. Updated October 1, 2016. https://content.legislation.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/d02c56bb-ecc8-31be-b7d9-6ac1b7cdbb12_14-78aa002%20authorised.pdf. Accessed 28 Jun 2022

Cancer Australia AG. Improving Cancer Data 2022. https://www.canceraustralia.gov.au/research/data-and-statistics/cancer-data/improving-cancer-data. Accessed 11 Aug 2022

Thomas DB (2002) Alternatives to a national system of population-based state cancer registries. Am J Public Health 92(7):1064–1066

Wormald JS, Oberai T, Branford-White H, Johnson LJ (2020) Design and establishment of a cancer registry: a literature review. ANZ J Surg 90(7-8):1277–1282

Parkin DM (2006) The evolution of the population-based cancer registry. Nat Rev Cancer 6(8):603–612

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD et al (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Bmj 372:n71

Sullivan GM (2011) Deconstructing quality in education research. J Grad Med Educ 3(2):121–124

Cook DA, Reed DA (2015) Appraising the quality of medical education research methods: the Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale-Education. Acad Med 90(8):1067–1076

Kiger ME, Varpio L (2020) Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE Guide No. 131. Med Teach 42(8):846–854

Jiagge E, Bensenhaver JM, Oppong JK, Awuah B, Newman LA (2015) Global surgical oncology disease burden: addressing disparities via global surgery initiatives: the University of Michigan International Breast Cancer Registry. Ann Surg Oncol 22(3):734–740

Chen AM, Kupelian PA, Wang PC, Steinberg ML (2018) Development of a radiation oncology-specific prospective data registry for research and quality improvement: a clinical workflow-based solution. JCO Clin Cancer Inform 2:1–9

Auffenberg GB, Ghani KR, Ramani S, Usoro E, Denton B, Rogers C et al (2019) askMUSIC: Leveraging a clinical registry to develop a new machine learning model to inform patients of prostate cancer treatments chosen by similar men. Eur Urol 75(6):901–907

Joishy SK, Driscol JC (1989) The ailments of cancer registries: a proposal for remedial education. J Cancer Educ 4(1):17–31

Struth D (2017) Oncology Qualified Clinical Data Registry: a patient-centered, symptom-focused framework to guide quality improvement. Clin J Oncol Nurs 21(6):755–757

Burton RC (2002) Cancer control in Australia: into the 21(st) Century. Jpn J Clin Oncol 32(Suppl):S3–S9

MacCallum C, Skandarajah A, Gibbs P, Hayes I (2018) The value of clinical colorectal cancer registries in colorectal cancer research: a systematic review. JAMA Surg 153(9):841–849

Meiser B, Monnik M, Austin R, Nichols C, Cops E, Salmon L et al (2022) Stakeholder attitudes towards establishing a national genomics registry of inherited cancer predisposition: a qualitative study. J Community Genet 13(1):59–73

Rothenmund H, Singh H, Candas B, Chodirker BN, Serfas K, Aronson M et al (2013) Hereditary colorectal cancer registries in Canada: report from the Colorectal Cancer Association of Canada consensus meeting; Montreal, Quebec; October 28, 2011. Curr Oncol 20(5):273–278

Yardley S, Dornan T (2012) Kirkpatrick's levels and education 'evidence'. Med Educ 46(1):97–106

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization (JL, DP, AB, AH, PS and HM); methodology (JL, HCT, KL, and HM); investigation (JL, HCT, KL); writing — original draft preparation (JL, HCT, KL); writing — review and editing (JL, HCT, KL, CW, KLC, JM). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 26 kb)

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, J., Temperley, H.C., Larkins, K. et al. Evaluating the Educational Value of Cancer Registries — a Systematic Review and Thematic Analysis. J Canc Educ 39, 194–203 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-023-02394-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-023-02394-6