Abstract

This article presents initiatives undertaken by the Department of Global Health and Social Medicine (GHSM) at King’s College London (KCL), exploring avenues to decolonise higher education institutions (HEI). HEI must integrate anti-racism agendas, challenge the European-centric academic knowledge domination, and dismantle power asymmetries. During the academic year 2021, GHSM executed (1) a gap analysis of undergraduate modules, (2) a course on decolonising research methods taught by global scholars to 40 Global South and North university students who completed pre- and post-course surveys, and (3) semi-structured interviews with 11 academics, and a focus group with four students exploring decolonising HEI; findings were thematically analysed. (1) Gap analysis revealed a tokenistic use of Black and minority ethnic and women authors across modules’ readings. (2) The post-course survey showed that 68% strongly agreed the course enhanced their decolonisation knowledge. (3) The thematic analysis identified themes: (1) Decolonisation is about challenging colonial legacies, racism, and knowledge production norms. (2) Decolonisation is about care, inclusivity, and compensation. (3) A decolonised curriculum should embed an anti-racism agenda, reflexive pedagogies, and life experiences involving students and communities. (4) HEI are colonial, exclusionary constructs that should shift to transformative and collaborative ways of thinking and knowing. (5) To decolonise research, we must rethink the hierarchy of knowledge production and dissemination and the politics of North-South research collaborations. Decolonising HEI must be placed within a human rights framework. HEI should integrate anti-racism agendas, give prominence to indigenous and marginalised histories and ways of knowing, and create a non-hierarchical educational environment, with students leading the decolonisation process.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The twenty-first century has seen resurgent and insurgent decolonisation at a global level. Movements such as “Why is my curriculum so White” (Peters, 2018), “Rhodes must fall” (Chaudhuri, 2016), and “Black lives matter” (Francis & Wright-Rigueur, 2021) ignited calls for decolonising higher education institutions (HEI) and “intellectual decolonisation” by challenging the colonial legacy within academia including curricula, pedagogies, classrooms, research methods, and knowledge production (Bhambra et al., 2020; Gopal, 2021; Hlatshwayo, 2021; Moosavi, 2020, p. 332; Peters, 2018; Phoenix, 2020; Tuck & Yang, 2021).

In this article, we seek to contribute to broader decolonisation projects across the globe by discussing our efforts towards a decolonised HEI. We first reflect on the contested term decolonisation, followed by an overview of the decolonisation efforts in HEI in the United Kingdom (UK). We then present a few of our decolonisation initiatives in the Department of Global Health and Social Medicine (GHSM) at King’s College London (KCL) in the UK. Our initiatives include (1) a gap analysis exercise of undergraduate core modules, (2) a pilot course on decolonising research methods, (3) interviews with academics and a focus group with GHSM students on decolonising HEI, (4) a workshop with GHSM students and academics on decolonising curriculum and research methods, and (5) a public symposium on decolonising knowledge production. Due to the limited word count, this article focuses on the first three initiatives. The projects were funded by KCL and conducted by members of the GHSM Anti-racism Steering Group (ARSG), founded in 2020 following students’ request to recognise racism and address the Black and Minority Ethnic (BME)Footnote 1 student attainment gap.

Positionality statement

This article is written from the position and experience of academics and students affiliated with universities primarily in the Global North, except for HK, an Arab Muslim woman who studied in the USA and UK and currently resides in the occupied Palestinian territory. NT is a Palestinian-British Muslim woman. EJ is a Black British Nigerian woman. MAJ is a Black African woman. OGTV is a multi-ethnic Mexican gay man.

It is vital to highlight that reflexivity has been at the core of our work; we acknowledge that our desire to decolonise risks compliance or maintenance of colonial, neo-colonial, and post-colonial monolithic global discursive asymmetry of power structure (Abdelnour & Abu Moghli, 2021; Chakraborty et al., 2017). While we feel uncomfortable using the divisive Global North (GN) and South (GS) terminology, we aim to show that we actively reach out to voices missing from our curriculum. We endeavour to challenge our unconscious biases and confront the West colonial past and “how its legacy continues to create inequities and injustices in the world we live in today” (Wong et al., 2020, p. 3).

Our work is informed by critical race theory (CRT), an analytical framework that addresses racial inequities in societies. CRT’s five tenets are (1) counter-storytelling that “legitimizes the racial and subordinate experiences of marginalized groups”; (2) the permanence of racism, where “racism controls the political, social, and economic realms of society”; (3) whiteness where whites have the right of usage, enjoyment, disposition, and exclusion; (4) interest conversion where whites are the main beneficiaries of civil rights legislations; and (5) the critique of liberalism linked to “colour blindness, the neutrality of the law, and equal opportunity for all” (Hiraldo, 2010, p. 54). CRT helps to understand the systemic racism that embeds in our societies and “the manner in which supposedly race-neutral institutions, systems, policies, and practices maintain white supremacy” (Crenshaw et al., 1995 in Kelly et al., 2020, p. 1372).

The roots of decolonising higher education

“Decolonisation” is a contested term that has a multiplicity of heterogeneous definitions, interpretations, aims, perspectives, and approaches, encapsulating different political, economic, cultural, philosophical, and epistemic dimensions, tracing 500 years of history (Adefila et al., 2022; Bhambra et al., 2018; Hayes et al., 2021; Bhambra et al., 2020; Pete, 2018; Von Bismarck, 2012).

It is essential first to understand colonisation and its legacies, characterisations, forms, and practices (Adefila et al., 2022). The Peruvian thinker Aníbal Quijano developed the concepts of “coloniality of power” and “coloniality of knowledge” and defined “Eurocentered colonialism” as the direct colonial domination Europeans practised over the political, social, and cultural dimensions of the conquered across the globe (Quijano, 2007, p. 168). Quijano described four interrelated domains forming the “colonial matrix of power,” where Eurocentered colonialism controlled (a) colonies’ economy through land appropriation, exploitation of labour, and control of natural resources; (b) authority through institutions and army; (c) gender and sexuality by dominating family and education; and (d) subjectivity and knowledge by dictating epistemology and formation of subjectivity (Mignolo, 2007; Quijano, 2000, 2007).

While direct political colonialism diminished, the specific colonial structure of power created systems of social discrimination, where colonisers were ranked at the top of social and economic structures, impeding the cultural production of the dominated by repressing “modes of knowing, of producing knowledge, of producing perspectives, images, and systems of images, symbols, modes of signification, over the resources, patterns, and instruments of formalized and objectivised expression, intellectual or visual” (Quijano, 2007, p. 169).

There is no consensus on defining decolonisation and what it entails (Gopal, 2021; Von Bismarck, 2012). Mignolo, for example, argues that “the major and vital move is to delink from the “colonial matrix of power” (Mignolo, 2018; Nanibush, 2018). While Fanon sees decolonisation as a violent process where the colonised liberate themselves politically and psychically (Fanon, 1971 in Etherington, 2016), Adébísí, in turn, asserts the vitality of understanding the contextual-based evolutions of decolonisation’s theories and sees that decolonisation “seeks the abolition of the ongoing and evolving structures of violent exploitation including the epistemologies that keep them in place” (2023, p. 15).

The varied discourses of decolonisation were rooted in colonised countries challenging imperialism during the colonial era (Mignolo, 2011; Zembylas, 2018). Although “intellectual decolonisation” gained prominence in the GN since 2014/15 (Moosavi, 2020, p. 332), decolonising movements emerged in the early twentieth century when Black and Asian anti-colonial and liberation scholars in India and Africa called for intellectual resistance for freedom and independence from British rule, to challenge the domination of Euro-centric thoughts (Arday and Mirza, 2018). Scholars from across the globe have significantly contributed to decolonial thinking, such as the French West Indian psychiatrist Franz Fanon (1925–1961), the Jamaican British feminist Una Marson (1905–1960), the Malaysian intellectual Syed Hussein Alatas (1928–2007), the Nigerian intellectual Claude Ake (1939–1996), and the Palestinian-American Edward Said (1935–2003).

Decolonising higher education

Neo-liberalised HEI are considered spaces that intensify “the logics and rationalities of coloniality,” built upon a “violent monologue” denying and violating the “knowing-be-ing” of other races (Motta, 2018, p. 25). Decolonising HEI requires “confronting the white occupation of academic knowledge and unsettling its grip over mundane as well as high stakes decisions” (Zeus Leonardo in Arday and Mirza, 2018, p. 3), besides the need for “congruent social processes that support human rights and inclusive knowledge generation” (Kennedy et al., 2023, p.1). Oppression and marginalisation practices, such as sexism, racism, and Islamophobia, are reproduced through educational processes (Osler, 2016). Therefore, decolonising HEI must embed human rights principles, including universality, indivisibility, equality and non-discrimination, participation, and accountability (UN Sustainable Development Group, 2023). Adébísí (2023, p. 33) asserts that “[D]iversifying the face of coercive power is not the same as dismantling it,” confirming the need to interrogate the “entanglement between knowledge and power, across space–time, as well as the evolution of resistance to this entanglement.” While there is no consensus on how a decolonised HEI looks, GN and GS HEI started movements to decolonise curricula, pedagogic practices, and institutional cultures.

HEI increasingly recognise they are key sites where coloniality occurs and Western knowledge is “produced, consecrated, institutionalised and naturalised” (Bhambra et al., 2018, p. 5). Discussions around curriculum involve three levels: explicit, hidden, and null curriculum (Le Grange, 2016). The explicit curriculum is what is presented to students, such as reading lists, assessments, and modules’ frameworks. The hidden curriculum is the underlying “unspoken or implicit values, behaviors, and norms” that shape the dominant university culture (Alsubaie, 2015, p. 125). The null curriculum is what is missing from the curriculum (Le Grange, 2016). It is essential for decolonising initiatives to address all curriculum levels.

Scholars also highlighted three concepts to consider when designing decolonised curricula and pedagogic practice: (1) epistemic silences that marginalise indigenous/local cultures, (2) negation that excludes non-Western theories and impose Western ideals, and (3) grand erasure that erase the experiences of most people around the world (Gaio et al., 2023, p. 4). Centring voices of the sufferers of inequity in curricula improves the learning experiences and strengthens the epistemological power of Black, indigenous, and GS students (Ahmed-Landeryou, 2023, p. 4).

Several UK HEI embarked on efforts to decolonise curricula, for example, SOAS (2018) “Decolonisation Toolkit,” UCL (2018) “Inclusive Curriculum Health Check,” Kingston University London (2020) “Inclusive Curriculum Framework,” and the University of Brighton (2019) “Decolonising the Curriculum: Teaching and Learning about Race Equality.” Most of these efforts do not explicitly explain how they developed their frameworks from evidence; hence, Ahmed-Landeryou (2023) conducted a scoping review to guide decolonising curricula. Ahmed-Landeryou introduced an evidence-informed framework highlighting key themes, such as the need to teach and learn about race inequality, introduce innovative assessments, secure leadership commitment and investment, make structural changes, involve students in change-making, and create meaningful outcome measures.

Although decolonisation is not exclusively about diversifying reading lists (i.e., the explicit curriculum), it is often the first step HEI employ. Evaluating reading lists often focuses on who are the dominant voices in disciplines, which voices are (intentionally) excluded, and what counts as legitimate knowledge. For instance, an evaluation by Schucan Bird and Pitman (2020) found an equal proportion of women and men authors within social science-based reading lists in one UK university. However, over 90% of authors were identified as “non-BME,” and 99% were affiliated with GN institutions. On the science-based reading lists, 70% of authors were men, 65% were identified as White, and 90% were based in GN.

Barriers to diversifying reading lists and decolonising curriculum efforts are contextual and structural, including rigid institutional policies, lack of leadership support, lack of access to resources including knowledge, funding and personnel, difficulty in identifying pure local or indigenous knowledge, academics feeling overwhelmed, overworked, and underpaid, and lack of recognising power dynamics around issues of gender, race, immigration status, and class (Loyola-Hernández & Gosal, 2022; Shahjahan et al., 2022). Laakso and Hallberg Adu (2023) presented specific challenges linked to decolonising curricula in Botswana, Ghana, Kenya, and Zimbabwe, including resources scarcity for research, lack of opportunities to publish research, difficulties in finding and producing textbooks with locally relevant perspectives, bureaucratic obstacles to accepting new course content, “the prevailing hegemonic structures of global academia and the subordinate position of African universities” (p. 13). Other scholars further highlighted limitations of “intellectual decolonisation,” such as ignoring GS decolonial theories, “reducing intellectual decolonisation to a simple task; essentialising and appropriating the GS; overlooking the multifaceted nature of marginalisation in academia; nativism; and tokenism” (Moosavi, 2020, p. 332).

Regarding decolonising research methods, indigenous scholar Smith describes conducting research with indigenous communities, placing their voices and epistemologies at the centre. Scholars argue for (re) gaining control over indigenous ways of knowing and being, critiquing traditional research approaches to indigenous life that historically addressed the concerns and interests of non-indigenous scholars, marginalised, oppressed, and dismissed non-Western knowledge production, and for creating new approaches of equal collaboration and participatory research, where power is located within the indigenous practices (Bishop, 2005; Datta, 2018; Denzin et al., 2008b; Keikelame & Swartz, 2019; Smith, 2021).

Our projects contribute to the literature and ongoing efforts toward decolonising curriculum and research methods. Next, we present our initiatives and findings. We conclude with the discussion and our outlook.

Methods

During the academic year 2021, GHSM embarked on several decolonisation initiatives:

-

(1)

A gap analysis exercise of all GHSM undergraduate (UG) core modules for 2020/2021.Footnote 2 We recruited three UG student research assistants who evaluated seven core modules, supervised by NT and another lecturer. The weekly reading list containing both core and recommended readings was exported to an Excel sheet, extracting the following information: the study location, author's ethnicity, gender, and institutional affiliation.

-

(2)

A 3-day intensive hybrid course on decolonising research methods, advertising the course on KCL social media platforms and across our global networks, including social media, and inviting experts on decolonisation from KCL and GN and GS institutions to teach the course. The lecturers were paid £100 honorarium. They came from Cape Town, Latin America, Colombia, The occupied Palestinian territory, Australia, New Zealand, and the UK. The course was led by NT and two research assistants, OGTV and HK. The team developed, implemented, and evaluated the course. A handbook was developed with the invited speakers (Supplementary Material 1). The invited speakers engaged in person and virtually with the attendees using different techniques to encourage interaction. Attendees had access to the recorded lectures (by speakers’ authorisation). The funded course was open to GHSM and partner universities’ students. Forty students attended the course: 23 from KCL, 12 from GS universities, five from GN universities, and three from GS non-government organisations. Sixteen participants completed the baseline questionnaire collecting demographic data, baseline knowledge, and course expectations. Twenty-five completed a post-course evaluation.

-

(3)

Semi-structured interviews discussing decolonising HEI with 11 academics and a focus group with four students (sample characteristics, Table 1). Interview participants included symposium and course presenters and GHSM academics who were approached via email. Focus group participants included GHSM students who were invited to partake by email and social media platforms. Although we invited all students, only four third year, non-white students joined the focus group. On reflection, we must increase the awareness of the colonisation’s effect on HEI among our students to encourage their engagement. Open-ended questions for interviews and the focus group explored motivations to join the research, the meaning of decolonisation, the vision of a decolonised HEI, decolonising the curriculum and research methods, and barriers to decolonisation (Topic guide, Supplementary Material 2). Interviews and the focus group were audio recorded and transcribed by MJ. NT applied thematic analysis, as Braun and Clarke (2006) described, while HK reviewed the codes and themes to increase validity. To strengthen validity and reflect decolonisation values, we invited participants to provide feedback on this article before submission.

One participant asked to be identified, but we must adhere to the ethical approval requirement of anonymity. Ethical approval was obtained through KCL minimal risk process. We were aware that some participants might have experienced kinds of oppression, such as racism or sexism. Hence, the participation was voluntary and anonymised; participants knew they could stop the interview if they felt uncomfortable. Interviewing the HEI management group would have enriched our findings. However, we were interested in exploring students’ and academic perspectives before conducting a future study with the management.

The findings

-

(1)

The findings of the undergraduate core module gap analysis

To explore the diversity and global representation in our reading materials, we addressed the following questions:

-

(a)

Who are we learning from?

-

(b)

How central are different gender and ethnic perspectives to our curriculum?

-

(c)

Which places are we learning about?

-

(d)

Who constitutes our experts?

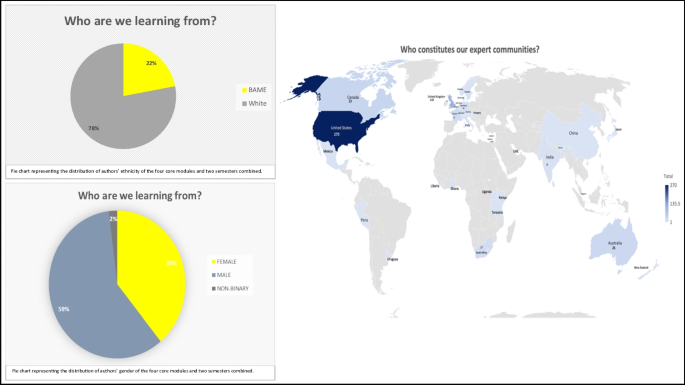

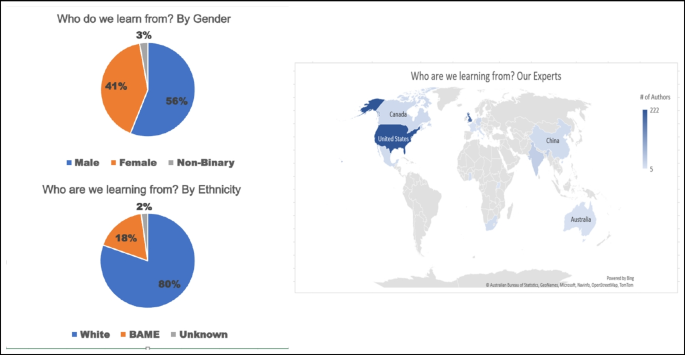

Our review highlighted four critical areas of concern. (1) A tokenistic use of BME, women, and declared non-binary authors across the modules’ readings. In the first year modules, there were 599 authors. 39% were women, 59% were men, and 2% declared non-binary. BME authors did not constitute above 30% of the total readings. In the second and third year modules, there were 546 authors. 41% were women, 56% were men, and 3% declared non-binary. (2) Most of the perspectives originated from men and non-BME authors. In the first year modules, 22% of authors were identified as BME and 78% as white. In the second and third year modules, 18% were identified as BME. Women only appeared as first authors in 36% of first year modules and 39% in the second and third years. Most of them were in recommended readings. Similarly, BME authors only appeared as first authors 21% of the time, mainly as authors of recommended readings. (3) Most learnings were about GN or GS from GN perspectives. In the first year modules, 64% of study locations were from North America or Europe, 2% were from Oceania, and 3% from South America. In the second and third years, 68% of study locations were from GS regions, 6% were from Europe, and less than 1% were from Oceania. (4) Authors were mainly from GN. For example, in the first year, 270 were from the USA, 118 were from the UK, 17 were from South Africa, and six were from India. In the second and third years, 220 were from the USA, 187 were from the UK, 37 were from India, and 15 were from South Africa (Figs. 1 and 2).

There were challenges while executing the gap exercise. Some decisions might have impacted the findings. For example, when recording the geographical locations of independent scholars versus those with institutional affiliations, we classified independent scholars according to their current geographical location (country and continent). Also, we acknowledge that delving into modules might give a different perspective than the reading list suggests. However, this was beyond the scope of the mapping exercise.

-

(2)

The findings of Decolonising Research Methods in Global Health and Social Medicine course

From 7th–9th of June 2022, 40 participants from diverse ethnic backgroundsFootnote 3 joined the course from 10:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. GMT. It aimed to bring various decolonising efforts and ongoing initiatives into the conversation to explore the limits of mainstream Western research methodologies and learn about indigenous research practices and methods. The lecturers presented qualitative and quantitative research case studies. Using the decolonisation lens, they discussed epistemologies of health, ethical research practices, reflexive research, and lessons learned from indigenous practices. OGTV simultaneously translated one lecture from Spanish to English. Four key themes emerged to promote an equitable research process: Recognising power dynamics, fostering collaborative research with indigenous researchers and participants, challenging dominant knowledge paradigms and embracing South-to-South epistemologies, and including indigenous concepts within ethical frameworks.

The pre-course survey compared to the post-course survey: 16 respondents completed the pre-course survey on SURVEY MONKEY. 75% showed unfamiliarity with indigenous or non-Western research methodology. Almost 88% have not received training in decolonising research methods, and their confidence in their knowledge was either not or a little confident. Respondents wanted to enhance their knowledge and skills in decolonising and conducting research more relevant to local communities. Twenty-five respondents completed the post-course survey. All respondents either agreed or strongly agreed the course was well delivered, the topics were comprehensive and clearly presented, and the supporting materials were helpful. 68% strongly agreed, and 28% agreed the course enhanced their decolonising research knowledge. 52% strongly agreed, and 40% agreed their understanding of the subjective experience of research participants increased. 64% strongly agreed, and 36% agreed they developed an awareness of the risks of using Western research methods when researching indigenous communities. All participants strongly agreed or agreed that the course made them aware of potential biases, risks, and oppression practices while conducting research, understand what emotional safety for researchers is, and be more aware of research ethics related to university settings. The majority strongly agreed or agreed that they developed more awareness of participatory and collaborative research, positionality as a researcher, and methodologies to redesign colonial space and create more ethical research.

In the post-course qualitative part of the survey, respondents mentioned the course widened their perspectives and provided new insights. One noted, “It made me more aware of the degree to which current research methodologies and approaches do not reflect the vast different types of communities and cultures.” Participants reflected on current research practices. One respondent said, “It sheds light on many ways research methodologies are colonised/../ and ways to decolonise them. It also highlighted/../ a hierarchy of knowledge, things I used to take for granted but are so unfair and unjust.” Another respondent wrote, “Throughout my undergraduate course, I was taught Western-style pedagogy. I had no idea about the indigenous perspective or ‘the researched’ perspectives. This course, however, helped me to unlearn this aspect”. One respondent mentioned that getting exposed to decolonising research provoked frustration. However, the course provided tools and possible action plans and clarified their position as researchers.

Participants considered the emphasis on diversity and the variable backgrounds of lecturers, participants, and topics a key strength. The course was described as a safe, collaborative, and engaging space that was eye-opening to participants. One respondent wrote: “This course enabled me to learn explicitly about positionality, critical reflexivity, reciprocity, respect and power relation/../. I am thankful to the organisers.” Another respondent wrote, “It was an amazing experience. This diversity makes me think critically. It gives light and confidence to us (GS) that we have also strong resources to do research. We are not dependent on the West at all.”

We faced a few challenges during the course. First, while the hybrid provision enhanced accessibility allowing participation from outside the UK, there were a few technical issues related to the Internet connection. Second, while lecturers endeavoured to encourage interaction, online participants were less interactive than in person. Third, while we intended this introductory pilot course to be intensive, participants preferred a longer duration. Finally, we acknowledge that using English as the primary communication language and enrolling English-fluent students is an exclusionary practice that does not fit the decolonial vision. We recognise that using native languages increases the sense of belonging in the classroom and student success (Wawrzynski & Garton, 2023). For future courses, we would foster student communication using indigenous languages, which effectively removes structures that perpetuate inequities (Schreiber & Yu, 2016).

-

(3)

The findings of semi-structured interviews and the focus group

We identified the following five themes and subthemes.

-

1.

Decolonisation is about challenging colonial legacies, racism, and knowledge production norms. Participants were aware of the heterogeneity and ambiguity of the meaning of decolonisation; however, they agreed decolonisation entails challenging colonial legacies, racism, and knowledge production norms. Student B questioned using the term decolonisation as they saw it as a way for “Western countries to enforce their ideologies” to avoid facing racism; the student thinks that “using the term decolonisation/../is steering away from the word racism.” Similarly, interviewee 9 described the language of decolonising as “ambiguous” and questioned how it relates to the anti-racism project, “we have power imbalances too, between junior and senior researchers, we have power imbalances between genders, and sometimes the colonial lens doesn’t help us address that problem/…/the legacies are there, and I see them, and it’s important to trace them through and to make them visible. But then there are a lot of power problems and silencing mechanisms that cannot be captured in the colonial terms that I still want to get at.” For interviewee 6, “There is somehow lines blur between anti-racism and decolonising and I'm not sure to what extent they're separate, overlap or the same.” Participants acknowledged histories of white domination and underscored that decolonisation is about challenging white supremacy through structural changes. Interviewee 2 asserted the need to “subvert the dominance of white culture and power.” Interviewee 8 confirmed the necessity to “dismantle the colonial gaze while simultaneously elevating the local systems, institutions, and processes.” Interviewee 11 emphasised the need for a “structural shift” by acknowledging “historiographical, residual, and also emergent complexities that we have to deal with” and “a strive towards translation and exchange of ideas and be mindful of kind of genealogies of these ideas and comparative relations that they come to generate,” and, as Interviewee 7 mentioned, by striving “towards translation and exchange of ideas.” Interviewee 8 discussed structural changes, such as publishing within the African publishing system to “decentralise knowledge production, [and] move from Eurocentric domains.”

-

2.

Decolonisation is about care, inclusivity, and compensation. Some participants saw decolonisation as a form of social justice to care for others and be inclusive to all humanity. Interviewee 4 clarified, “It [decolonising] is embedded in a true sense of care.” Participants explained the importance of diversifying knowledge and the inclusion of indigenous voices. Interviewee 1 explained, “Decolonising by default requires us to include the voices of indigenous people and for them to be real people, not just in books and in our curriculum. It requires us to link up with the rest of the world differently.” Inclusivity involves conversation, as interviewee 11 emphasised that “decolonisation is about conversation/../it’s not about silencing; just putting something that has been silenced in the foreground and then silencing what has been in the foreground, putting that in the background, I think that’s a dead end.” For Student D, inclusivity means taking away all forms of “discrimination, racial discrimination, segregation, and division.” For others, decolonisation is about empowering, recompense, compensation, giving back land, and reparation. As Interviewee 6 said, decolonisation is about giving back “land,” “authority,” “sovereignty,” “history,” “artefacts,” and “money” and “paying reparations.” Similarly, Student A said, “I think we’ve gone past the point of giving people a seat at the table, and we would need to build a whole new table and replace the ones that we/../as in colonial institutions and powers have broken and taken away.”

-

3.

A decolonised curriculum should embed an anti-racism agenda, reflexive pedagogies, and life experiences involving students and communities. When discussing decolonising the curriculum, five subthemes were recognised:

Embed anti-racism agenda

Participants highlighted the importance of having an anti-racism lens embedded within the curriculum. Interviewee 2 stated that decolonising curriculum should be about “consciousness-raising” and thinking about power structures. Interviewee 6 believed that “anti-racist agenda/../feeds into the decolonising agenda.” Interviewee 1 wanted to allow students to critique authors’ writings “from a racialised perspective,” acknowledging the source of our knowledge and emphasising that one way “in which colonisation exists is through the presentation of knowledge from the GS as if it has been derived solely from the GN.” Student A wanted the teaching about race to be compulsory, highlighting a lack of white students’ presence in modules addressing racism, “we only have one white person in our class now, so it's good because it’s a safe space, but it's bad because it’s just preaching to the choir, the people who should be learning about all of the history and context behind racism and especially its intersections with health are not there.”

Diversify perspectives

Participants confirmed the necessity to include diverse knowledge and perspectives when teaching the curriculum, emphasising that decolonisation efforts should not only focus on the tokenistic act of diversifying the reading list but also reflect on the content and history of knowledge. Interviewee 7 confirmed that “geographical diversity of reading material is a cop-out answer.” Interviewee 3 highlighted that when designing a curriculum, we need to think “about who writes it and whose perspective is it” and clarify to students the rationale of having a specific reading list. Student D believed that decolonisation should look at “what kind of knowledge is shared” and learn about the colonial past to be “more truthful, more accurate, and more representative of the history.” Student C confirmed the need for “diverse readings that are, for example, by authors from more diverse backgrounds and academics who are probably not from like the West.” Interviewee 11 asserted that all knowledge is valuable and warned against demolishing the current curriculum: “Just because something of political or historical context has been overlooked and oppressed doesn't mean that paper is suddenly not valuable.”

Embrace reflexivity

Participants confirmed that reflexivity must be at the core of curriculum decolonisation, where students and staff reflect on their positionalities, biases, and histories, paving the way for including all kinds of knowledge. Interviewee 7 called for “commitment to critically reflect on how colonialism continues to pervade the global health field,” including our disciplines, research, teaching, and higher education. Interviewee 9 believed that reflexivity through “pointing out your own limitations and constraints and failings is actually the road of creating spaces for others to speak.” Interviewee 4 suggested reflecting on the reasons for teaching particular subjects, their relevance to the local community, and responsiveness to multicultural students. Interviewee 6 reflected on extracting indigenous methods to decolonise curriculum: “To what extent are we just extracting methods that really fit very nicely our sort of modernisation of the curriculum? They just fit very nicely into what we're trying to do anyway. How practical that we can now take it again from the GS and extract and apply it here in order to improve our own sort of pedagogical practice.” Positionality was a key concept to participants, as Interviewee 6 confirmed the need to “acknowledge where we are from and the privileges that this brings [and] the limitations.” Interviewee 5 asserted that students and staff must embrace reflexivity “to think about their own positionality, their own power, their own practice.” Interviewee 10 said, “I always say at the beginning of my class, it’s uncomfortable for me /../ We don’t have someone to teach you this who is Black, who has that experience. So, I have a choice of not teaching you/../ or doing so as a white man.”

Incorporate life experiences and communities

Participants highlighted that the curriculum should link to life experiences and communities (Interviewees 2, 3, 4, 5). Interviewee 2 pointed to including pedagogies with a “real-world element to it,” leading to an action embedded within communities and mutual learning between students and academics. Interviewee 3 highlighted the usefulness of connecting to indigenous movements to guide the decolonising process. Interviewee 5 mentioned that students must speak to communities and indigenous people and learn from them, “It could be really amazing to have people who are much more embodied and community practice-oriented talking about decolonising /../ breaking the structures we’re in, the patriarchal colonial imperial structure as they understand it and reconfiguring ourselves as humans.” Interviewee 4 asserted that community should be at the heart of a decolonised HEI where community members sit on university boards to understand “what an ordinary man/../ understands about decolonising.”

Engage students

Participants confirmed students’ role is vital in decolonising the curriculum as they should reflect on the curriculum and their learning experience and be active agents of change. Interviewee 8 wanted students to reflect on the colonial legacies and “be able /../ to name our own intersections, our position, where we come from.” Interviewee 6 asserted the need to teach the history of our disciplines “to make students fully aware that they are entering into a colonial system/../ they are becoming part of it /../ it is their responsibility how they carry that knowledge.” Interviewee 9 encourages students to reflect and be proactive: “I would invite the students to actually create spaces where they can challenge my way of knowing, where they can bring their own interests and priorities to say what we should be talking about.” Interviewee 6 highlighted the need to learn from GS students about their countries, histories, challenges, social structures, and norms.

-

4.

Higher education institutions are colonial, exclusionary constructs that should shift to transformative and collaborative ways of thinking and knowing

When discussing barriers and vision to decolonise HEI, we identified five subthemes:

HEI are colonial, exclusionary constructs

Participants agreed that the most significant barrier to decolonising HEI is their colonial structures and rigid ways of knowing dominated by white Eurocentric thoughts. Interviewee 1 described the education system as a “capitalist model,” part of the “racism agenda,” that adopts “masculinist norms” building on “patriarchal controlling structures /../ with a very narrowly defined concept of knowing/../ which doesn't create that many opportunities for new ideas.” Interviewee 7 said most university disciplines “have their foundations in very white Eurocentric scholarly traditions.” Student C also said that “these institutions being formed on colonial bases is something that really hinders the [decolonisation] process.” Interviewee 2 believed that some HEI structures are “oppressive/../rooted in colonising practices/.. and linked to prioritising certain people’s knowledge” while excluding others. Interviewee 2 also mentioned barriers such as “universities being a business,” “the university hierarchy,” and “the race pay gap.” Interviewee 6 talked about the nationalistic nature of HEI and the “bureaucratic political hurdles” that hinder decolonisation and enmeshment with GS institutions, “We work in highly structured institutions that have been developed during colonial times, and we’re only able to function the way they functioned because of these sorts of colonial ties, right? This is how we gained global knowledge. This is how disciplines like anthropology emerged/../. it’s along these colonial trajectories. This is how we came to know the world. Of course, there’s history before that, but still. And so, I think our institutions don’t really permit enmeshment because they’re very nationalistic.”

Attitudes towards decolonisation

Several attitudes were identified as barriers, such as shallow engagement with the decolonisation discourse, fear of change, and lack of time and funds. Student A highlighted the need to move from creating “a buzzword” or, as the Notetaker Student said, “a tick box exercise” where universities measure their diversity by the number of BME-hired people. Others talked about the apprehension and resistance to change, which Student C described as “a major hindrance.” Interviewee 1 talked about resistance to change: “We’re at the mercy of people at the political level who have a vested interest in maintaining the hegemony that has been established because if we were to get radical transformation, it would also mean that the people in power are no longer in power.” Interviewee 2 talked about some academics working on decolonisation to build careers rather than making a change. Interviewee 7 mentioned “the lack of rewarding.” Interviewee 1 pointed to insufficient time available to staff to work on decolonisation, the lack of funds, and “defaulting on the racialized people to do the hard craft,” primarily women, as Interviewee 5 indicated.

Collaboration with global south

Participants discussed the unequal nature of working with GS institutions; they envisioned a decolonised HEI with equal collaborative opportunities. Interviewee 11 said that we are an “elite institution” in a “powerful country” and must engage with GS institutions “on a much more equal ground.” Interviewee 9 talked about practising the concept of “mutuality” in partnerships and institutionalising humility by creating a “space of mutuality /../ where you have equity and equitable relationships at the bottom of everything/../ the fact that you’re not the expert while being fully aware that you have the resources, the funding, the building, the branding power.” Interviewee 6 wanted institutions to provide fellowships and exchange with GS scholars “but according to the terms of those ones needing and wanting to extract whatever it is that they want to extract. That has to be financed by us as a form of reparation and trying to make good in terms of what we have done so horribly wrong in the past.” Interviewee 5 wanted to see more GN and GS staff exchanges to learn from others.

Academics’ diversity

Academics’ diversity and making space for talented people of colour were mentioned as essential steps towards decolonising HEI. Interviewee 7 explained that the high fee is a barrier for BME students to join universities, hence the lack of BME scholars. Interviewee 6 highlighted, “Right now, we’re looking like the snowy white tops/../it becomes very white on top/../ that needs to change.” For Interviewee 10, a decolonised HEI “would have more Black and minority ethnic people in positions of power and authority.” Students also recognised the lack of diversity in HEI. Student B questioned, “Where do most of our lecturers come from? Where do they get their degrees, who can get into those institutions, and what hinders other people from getting into those institutions or getting to that level of education? Is it socioeconomic factors? Is it their location?” Similarly, student A also commented on the lack of academic diversity, “we’re going to an institution with a large colonial history, a very capitalist outlook on the world, and the professors, especially the older ones, have the same outlook so obviously they’re going to have their biases as they teach which will anyone would, but it would be nice to have a diverse amount of biases when teaching rather than the status quo.”

Fostering decolonisation

Participants acknowledged the importance of forwarding the decolonisation agenda within universities. They suggested creating informal spaces for debate and discussions. Interviewee 1 suggested having “sufficient pockets” in every university focusing on decolonisation and “to incrementally reduce some of the fear [of change].” Interviewee 4 confirmed the difficulty in changing existing attitudes and behaviours but recommended that a debate on decolonising should be fostered everywhere, “We need to talk about it more and exchange ideas and understand ourselves.” Similarly, Interviewee 8 envisioned conversations about decoloniality to be open and taken seriously by HEI. Interviewee 9 talked about creating safe spaces to challenge systems of oppression: “brave spaces/../where it’s about how can I safely challenge what’s around me. So how can I find the courage to call out the things that need to be called out?” Interviewee 2 called for free access to learning opportunities on decolonisation. Finally, participants praised some efforts on decolonisation in UK HEI, such as courses, students’ movements, collaborative projects, and inviting GS guest lecturers.

-

5.

To decolonise research, we must rethink the hierarchy of knowledge production and dissemination and the politics of North-South research collaborations

When discussing decolonising research, we identified the following seven subthemes:

Research as a colonial construct

Participants shared their views on the colonial roots of current research practices and criticised the assumption that global health should focus on GS. They acknowledged the colonial history of disciplines like Anthropology. Two interviewees (5,7) shared their concerns as white researchers conducting research in GS and wanted to see GS researchers doing this kind of research. Interviewee 7 said, “There is something inherently problematic about me as a white researcher based in a UK-based university, to go to places like Uganda trying to understand people and practices in these contexts/../ I would wish that there were Ugandan researchers who, if they think these are important projects or important things to look at, would be the ones doing that kind of research.” Others viewed research as a collaborative endeavour. Interviewee 6 believed that research is “a global convention” and a collaborative process where researchers across the globe have contributed to and shaped over time through “engaging in a global discourse by refining them [research techniques].” Interviewee 11 said that “there are things that should be dismantled and things that should be left to be improved” and explained that indigenous approaches and “modern scientific tradition” should be “genuinely collaborative.”

The knowledge we value

Participants highlighted the lack of value research communities hold for indigenous knowledge and the need to address the knowledge hierarchy. Interviewee 1 highlighted the link between racism and sickness, explaining that while for many years people of colour indicated racism made them sick, it was not until researchers from GN confirmed this link, “We now kind of place more value on it/../we need to/../be open to reviewing what we consider to be the hierarchy in the gold standard and why and actually what is excluded in that process.” Interviewee 4 called for the “need to look at different methods and how we incorporate those African or indigenous methods in our research.” She criticised the Eurocentric review mechanism for not valuing non-Western methods and mentioned “storytelling” as an indigenous method that could be used in research. Interviewee 10 called to rethink what “valuable knowledge is” and criticised “the dominance of English in academia.” Interviewee 4 highlighted issues with journal reviewers regarding the marginalisation of non-English languages and the domination of the English language: “Why should it only be English, if a person writes in Arabic that can be translated in English and then put the other one you know in the bracket so that the person who understands that can read that in context and understand what the person was saying.” Interviewee 7 highlighted authorship problems and the need to support and fund GS researchers, mentioning that 80% of research articles are produced in GN.

New ways of dissemination

Participants acknowledged the limitations of current research dissemination practices and suggested new ways to communicate research to communities. Interviewee 2 suggested that “decolonised research should be outside journals because a journal does not feel like an accessible way to get knowledge.” He wanted to see research that is not only written in English and that “happens outside of the universities, in the context of community organisations /../ through a collaboration with other parts of the world.” Similarly, Interviewee 3 saw new ways of dissemination outside universities, like exhibitions, where researchers present “findings to the public, inviting local people” and showing the research benefits to society. Interviewee 4 discussed using community channels to disseminate research findings, such as “community radio stations,” drama, music, stories and arts. Interviewee 8 wanted participants to present research and tell their stories.

Reflexivity

Participants placed reflexivity at the core of decolonising research practices, promoting reflection on who is doing the research, their biases, motivations, and backgrounds. Interviewee 1 talked about identifying the “hegemony” when conducting research and the impact of who is doing the research, “what do we privilege, what do we study, who do we have as researchers and to actually understand the conscious and unconscious processes that occur in the research practice.” Interviewee 7 confirmed the need to “critically reflect on our own knowledge production and how we know what we know and allow ourselves to be challenged.” Interviewee 11 believed that “there is value in multiplicity” and that the inherited research practices are not necessarily perpetuating coloniality; the interviewee emphasised that when conducting empirical research, “the question to ask is what potentially could be colonial through this research and what should be avoided to become decolonised.”

Equitable South-North collaboration

Participants confirmed that equal South-North collaboration is key to decolonising research with emphasis on recognising that funders influence and limit models of collecting information. Interviewee 3 highlighted that Western funders would keep dominating the research agenda unless the GS governments have the financial independence to do research. “The finance one is a huge one/../ [it] has to change because a lot of these studies are funded by the United States. So, it’s very difficult. So, unless the governments themselves are going to be, I want to run my study, I want to do this by myself. But then you have to have the financial independence to do that.” Interviewee 6 spoke about the imbalance of power dynamics due to funding “often comes with strings attached” where GN researchers lead research, money is not handed directly to GS researchers, research reflects GN interests, and is not co-designed with GS researchers. Interviewee 6 continued, “If these power dynamics are not changed and /../dismantled, we cannot have any form of equitable research.” Interviewee 8 also discussed global power discourses regarding knowledge production and spoke about the importance of equal pay, equal relationships between GN and GS researchers, and the need to support GS researchers. Interviewee 10 believed big institutions in wealthy, predominantly white countries should support researchers in GS countries rather than doing research with them or on them. Interviewee 6 also talked about researchers’ exchange: “I feel increasingly uncomfortable that researchers from the GN think that they should be the ones exploring life in the GS. Although I would have to say I would find it quite interesting if more researchers from the GS would come to the GN and actually study us and hold a mirror up. That hasn’t happened to the same degree. So, there is a big knowledge gap.”

Partnership with the researched

Participants highlighted the importance of shifting control over data and partnering with the researched. Interviewee 3 confirmed the need to partner with people “by investigating critical issues that indigenous people identify and giving them more control over the data/../ who has access to the data and what they choose to do with it.” Similarly, Interviewee 4 called for involving people in research “so that people must understand the research is/../ about working together /../ to address their issue of concern, not the issue of the researcher.” Interviewee 5 spoke about the need to be “humble” and “critical of our research” and “what you owe to people when you do research.” Interviewee 6 also asserted that researchers need to engage with communities “to understand how it is that they generate knowledge /../ and the question is also who has the right to extract that knowledge and for what purpose.” For Interviewee 8, a decolonised research “speaks to local systems and processes. It is research that responds to realities, and I understand that makes it difficult because we are obsessed with coming up with standards and systems and processes/../But I think when you are doing research in spaces that are different in terms of culture, ethnicity and geography, everything. I think what should define your research is the expectations of that culture, that system or that process and how things are done in that space.”

New approach to ethics

Participants wanted to see less rigid, Western-informed ethical procedures and more reflexive, collaborative, ethical processes responsive to communities’ needs and norms. Interviewee 4 wanted to have community members on the ethics review boards. Interviewee 5 envisioned a less formal ethical process with constant reflexivity and collective conversation among researchers. Interviewee 8 called for rethinking the ethical research norms by reflecting on ethical dilemmas, such as compensating research participants for their time by paying them, as he believed that “taking them away from their income [is] unethical in itself.” Interviewee 5 highlighted the importance of engaging with the researched and exploring “whether they see any of those processes within their own frameworks.” Interviewee 6 discussed co-producing research knowledge and ownership: “Ownership of the data needs to be shared, moving away from the extraction model.” While acknowledging the need to avoid harm, she, for example, questioned the value of anonymising participants: “If you anonymise everything and your data sets and then aggregate and disaggregate, the individual’s story gets lost. So, it’s difficult for the person to know what part of that study they actually owned. So, there is something to be said about anonymity.”

Discussion

Decolonising initiatives must question how Euro-centric knowledge is embedded in HEI and its hegemony over knowledge production compared to non-Western indigenous knowledge systems. This article presented our GHSM decolonising initiatives: (1) a gap analysis exercise of UG core modules, (2) a pilot course on decolonising research methods, and (3) interviews with academics and a focus group with students on decolonising HEI. Our initiatives contribute to the knowledge and efforts to decolonise HEI (Chaudhuri, 2016; Francis & Wright-Rigueur, 2021; Peters, 2018).

First, like Schucan Bird and Pitman’s (2020), our gap analysis exercise exposed our mainly white, biased curriculum towards GN scholars and research. Second, the pilot course expanded the horizons of our participants’ knowledge of decolonisation and indigenous research approaches. Finally, we identified the following themes by analysing our interviews and focus group: (1) Decolonisation is about challenging colonial legacies, racism, and knowledge production norms. (2) Decolonisation is about care, inclusivity, and compensation. (3) A decolonised curriculum should embrace anti-racisms agenda, reflexive pedagogies, and life experiences involving students and communities. (4) Higher education institutions are colonial, exclusionary constructs and should shift to transformative and collaborative ways of thinking and knowing. (5) To decolonise research, we must rethink the hierarchy of knowledge production and dissemination and the politics of North–South research collaborations.

Our research identified contextual and structural barriers to decolonise the curriculum: the colonial, exclusionary nature of the university’s construct, the colonial root of some disciplines; the apprehension and fear of, or resistance to change exhibited by some university staff; the lack of mechanisms to face power asymmetry and create equal collaboration opportunities between GN and GS institutions, the lack of academics’ diversity, and shortage of fund, time, space, and avenues to foster decolonisation in universities. These findings agree with other studies (Loyola-Hernández & Gosal, 2022; Shahjahan et al., 2022).

To decolonise the curriculum, our participants highlighted that an anti-racist agenda must be at the core of the HEI vision. This includes changing structures and policies to ensure diversity of staff; creating equal opportunities for people from different backgrounds; addressing the power imbalance at all levels, i.e., staff to staff, staff to students, students to students, and GN to GS; adopting reflexive pedagogies where colonial legacies are problematised and challenged; creating spaces for silenced voices to be heard and for indigenous and non-Western knowledge to be acknowledged and incorporated in learning; connecting learning to diverse communities and histories and ways of knowledge; and empowering students to lead the HEI decolonisation. Our findings reflect the themes proposed by Ahmed-Landeryou’s scoping review (2023) to guide decolonising curricula. Participants talked about explicitly diversifying reading lists. They criticised a university culture shaped by colonial practices. They pointed to missing voices, marginalisation of groups, domination of Western ideals and structures, and the grand erasure of non-Western experiences. Hence, reflecting the three curriculum levels (Le Grange, 2016) and Gaio et al.’s (2023) concepts in designing curriculum.

To decolonise research, our participants expressed a struggle with the inherited disciplinary practices rooted in colonial systems. They suggested steps to shift to a decolonised research through (1) rethinking the knowledge production and dissemination hierarchy, such as supporting publishing in non-Western journals in native languages; (2) changing the politics of North-South research collaborations by creating funded opportunities for GS researchers to conduct research in the GN; (3) partnership with people, so more participatory research and power shifting to the researched rather than the researchers and funding bodies; and (4) be reflexive of positionality and what Western ethical bodies consider ethical research practices versus what is relevant to different cultures and communities. These findings agree with the decolonising research literature (Bishop, 2005; Datta, 2018; Denzin et al., 2008a, b; Keikelame & Swartz, 2019; Smith, 2021).

Our findings concur with scholars calling for a decolonised HEI to confront the domination of white academic knowledge and power asymmetry (Adébísí, 2023; Zeus Leonardo in Arday and Mirza, 2018), placing the process within a human rights framework (Kennedy et al., 2023; Osler, 2016). Our findings speak to the tenets of CRT (Hiraldo, 2010): our participants envision a decolonised HEI where (1) experiences of marginalised groups are foregrounded, (2) an anti-racist agenda is adopted across all levels, (3) exclusionary white practices are challenged, (4) legislations are changed to benefit all people from all backgrounds, and (5) spaces are created to challenge colonial legacies.

Moving forward, we endeavour to be guided by our findings and others in the field. Addressing the identified limitations of “intellectual decolonisation” (Moosavi, 2020, p. 332), we plan to (1) incorporate decolonial theories and ways of knowing from the GS in our curricula. This is achieved through funding we gained from KCL to recruit a GHSM student to assist in creating a publicly accessible online archive. We have embarked on building the archive with GS collaborators and input from students and educators to help global health scholars in their decolonising efforts; (2) move away from a ticking box exercise to a process of continuous evaluation and reflection on curriculum, pedagogies, research practices, and positionality; this is achieved through an open dialogue with students and staff and one to one support to educators and researchers; (3) address marginalisation in academia through our efforts in the ARSG in collaboration with the Equality Diversity Inclusion Committee and other initiatives at KCL to foster spaces for conversation about race and inequity among staff and students, across all levels; and (4) actively seek funding to equally collaborate with GS researchers.

We agree with scholars that “Decolonization is not a metonym for social justice” (Tuck & Yang, 2021, p. 21) and “certainly not a substitute for material reparations” (Gopal, 2021, p. 880). We, however, believe that to understand race-based hierarchies embedded within HEI and to achieve social justice and racial equity in HEI, we must reveal the harm created by constructing white as a supreme race and document the “intellectual decolonisation” efforts to dismantle the power asymmetry and challenge the domination of Euro-centric thoughts. Hence, we document our efforts on decolonisation. We do not claim to be experts in decolonising HEI. However, by writing about our initiatives, we seek to build our knowledge and provide examples for others on the same journey. In the pursuit of decolonisation, it is essential that future curricula illuminate historical injustices where indigenous people are generators of knowledge and not just subjects for research and foster a more inclusive, ethically informed and just education. We acknowledge that systematic, structural colonial legacies are ingrained in our societies and that the journey to make changes is difficult. We also know our limitations in securing funding to continue our work and gain the institution’s full support. However, we believe collective efforts and determination to evolve would improve race inequities among future generations.

Conclusion

HEI must adopt strategies that are transformative, representative of, and responsive to the needs of their students’ cohorts and communities. Decolonising HEI must be placed within a human rights framework. A decolonised HEI would integrate anti-racism agendas; dismantle power asymmetries; challenge the European-centric academic knowledge domination; give prominence to indigenous and marginalised histories, theories, worldviews, and ways of knowing; foster multi-directional learning; create a non-hierarchical educational environment; and, most importantly, equip and allow students to lead the decolonisation process.

Data availability

The online archive that we mentioned in the conclusion has been designed and launched: https://globalhealtharchive2.wordpress.com/

Notes

We follow King’s College London guidelines which define ethnicity through the category of ‘BME’, encompassing six ethnic categories (White, Chinese, Black, Asian, other and mixed, unknown).

The modules that were analysed: Introduction to Social Medicine, Introduction to Global Health, Foundations in Social Science Theory, Research Practice and Design Studio. Key Concepts in Social Medicine, Key Concepts in Global Health, and Contemporary Crisis in Global Health and Social Medicine.

The countries represented at the course (in alphabetical order) were Argentina, Australia, Bangladesh, Belgium, Bermuda, Brazil, Canada, China, Colombia, Czech Republic, Ethiopia, Ghana, Greece, India, Indonesia, Lebanon, Malaysia, Mexico, Nepal, Netherlands, New Zealand, the occupied Palestinian territory, Philippines, Rwanda, South Africa, Spain, Tanzania, United Kingdom, United States, and Zimbabwe.

References

Abdelnour, S., & Abu Moghli, M. (2021). Researching violent contexts: A call for political reflexivity. Organization, 13505084211030646. https://doi.org/10.1177/13505084211030

Adébísí, F. (2023). Theories of decolonisation; or, to break all the tables and create the world necessary for us all to survive. Decolonisation and Legal Knowledge: Reflections on Power and Possibility, 14. https://doi.org/10.51952/9781529219401.ch001

Adefila, A., Teixeira, R. V., Morini, L., Garcia, M. L. T., Delboni, T. M. Z. G. F., Spolander, G., & Khalil-Babatunde, M. (2022). Higher education decolonisation: Whose voices and their geographical locations? Globalisation, Societies and Education, 20(3), 262–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2021.1887724

Ahmed-Landeryou, M. (2023). Developing an evidence-Informed decolonising curriculum wheel—A reflective piece. Equity in Education & Society, 27526461231154014. https://doi.org/10.1177/27526461231154014

Alsubaie, M. A. (2015). Hidden curriculum as one of current issue of curriculum. Journal of Education and Practice, 6(33), 125–128.

Arday, J., & Mirza, H. S. (Eds.). (2018). Dismantling race in higher education: Racism, whiteness and decolonising the academy. London: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-60261-5

Bhambra, G. K., Nişancıoğlu, K., & Gebrial, D. (2020). Decolonising the university in 2020. Identities, 27(4), 509–516. https://doi.org/10.1080/1070289X.2020.1753415

Bhambra, G. K., Gebrial, D., & Nişancıoğlu, K. (2018). Decolinising the university (p. 5). PlutoPress.

Bishop, R. (2005). Freeing ourselves from neo-colonial domination in research: A Kaupapa Māori approach to creating knowledge. In N. K. Denzin, ed. & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of Qualitative Research (3rd ed., pp. 109–138). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Chakraborty, K., Saha, B., & Jammulamadaka, N. (2017). Where silence speaks-insights from Third World NGOs. Critical Perspectives on International Business, 13(1), 38–53. https://doi.org/10.1108/cpoib-03-2015-0012

Chaudhuri, A. (2016). The real meaning of Rhodes must fall. The Guardian, 16, 16.

Crenshaw, K., Gotanda, N., & Peller, G. (1995). Critical race theory: The key writings that formed the movement. The New Press.

Datta, R. (2018). Decolonizing both researcher and research and its effectiveness in Indigenous research. Research Ethics, 14(2), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747016117733296

Denzin, N. K., Lincoln, Y. S., & Smith, L. T. (Eds.). (2008a). Handbook of critical and indigenous methodologies. Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483385686

Denzin, N. K., Lincoln, Y. S., & Smith, L. T. (2008b). Introduction: Critical methodologies and indigenous inquiry. Handbook of critical and indigenous methodologies, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483385686

Etherington, B. (2016). An answer to the question: What is decolonization? Frantz Fanon’s the wretched of the earth and Jean-Paul Sartre’s critique of dialectical reason. Modern Intellectual History, 13(1), 151–178. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1479244314000523

Fanon, F. (1971). The Wretched of the Earth [1961], trans. Constance Farrington.

Francis, M. M., & Wright-Rigueur, L. (2021). Black Lives Matter in historical perspective. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 17, 441–458. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-122120-100052

Gaio, A., Joffe, A., Hernández-Acosta, J. J., & Dragićević Šešić, M. (2023). Decolonising the cultural policy and management curriculum–reflections from practice. Cultural Trends, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/09548963.2023.2168515

Gopal, P. (2021). On decolonisation and the university. Textual Practice, 35(6), 873–899. https://doi.org/10.1080/0950236X.2021.1929561

Hayes, A., Luckett, K., & Misiaszek, G. (2021). Possibilities and complexities of decolonising higher education: Critical perspectives on praxis. Teaching in Higher Education, 26(7–8), 887–901. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2021.1971384

Hiraldo, P. (2010). The role of critical race theory in higher education. The vermont connection, 31(1), 7. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/tvc/vol31/iss1/7. Accessed 20 May 2022

Hlatshwayo, M. N. (2021). The ruptures in our rainbow: Reflections on teaching and learning during# RhodesMustFall. Critical Studies in Teaching and Learning (CriSTaL), 9(2), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.14426/cristal.v9i2.492

Keikelame, M. J., & Swartz, L. (2019). Decolonising research methodologies: Lessons from a qualitative research project, cape town, South Africa. Global Health Action, 12(1), 1561175. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2018.1561175

Kelly, S., Jérémie-Brink, G., Chambers, A. L., & Smith-Bynum, M. A. (2020). The Black Lives Matter movement: A call to action for couple and family therapists. Family Process, 59(4), 1374–1388. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12614

Kennedy, A., McGowan, K., & El-Hussein, M. (2023). Indigenous elders’ wisdom and dominionization in higher education: Barriers and facilitators to decolonisation and reconciliation. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 27(1), 89–106.

Kingston University London. (2020). Equality, diversity and inclusion. Inclusive Curriculum Framework, UK. Kingston University London. Available at. https://www.kingston.ac.uk/aboutkingstonuniversity/equality-diversity-and-inclusion/our-inclusive-curriculum/inclusive-curriculum-framework/. Accessed 10 Oct 2023.

Laakso, L., & Hallberg Adu, K. (2023). ‘The unofficial curriculum is where the real teaching takes place’: Faculty experiences of decolonising the curriculum in Africa. Higher Education, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-023-01000-4

Le Grange, L. (2016). Decolonising the university curriculum. South African Journal of Higher Education, 30(2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.20853/30-2-709

Loyola-Hernández, L., & Gosal, A. (2022) Impact of decolonising initiatives and practices in the Faculty of Environment. Report. University of Leeds. https://doi.org/10.48785/100/103

Mignolo, W. (2007). Introduction: Coloniality of power and de-colonial thinking. Cultural Studies, 21(2/3), 155–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380601162498

Mignolo, W. D. (2011). The Global South and world dis/order. Journal of Anthropological Research, 67(2), 165–188.

Mignolo, W. (2018). What does it mean to decolonize? In C. E. Walsh, & W. D. Mignolo (Eds.), On decoloniality: Concepts, analytics, praxis (1st ed., pp. 105–134). Duke University Press.

Moosavi, L. (2020). The decolonial bandwagon and the dangers of intellectual decolonisation. International Review of Sociology, 30(2), 332–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/03906701.2020.1776919

Motta, S. C. (2018). Feminizing and decolonizing higher education: Pedagogies of dignity in Colombia and Australia. In S. de Jong, R. Icaza, & O. U. Rutazibwa (Eds.), In Decolonization and feminisms in global teaching and learning (1st ed., pp. 25–42). Routledge.

Nanibush, W. (2018). Thinking and engaging with the decolonial: A conversation between Walter D. Mignolo and Wanda Nanibush. Afterall Journal, Retrieved April 2, 2023, from. https://www.afterall.org/article/thinking-and-engaging-with-the-decolonial-a-conversation-between-walterd-mignolo-and-wanda-nanibush. Accessed 2 Apr 2023

Osler, A. (2016). Human rights and schooling: An ethical framework for teaching for social justice. Teachers College Press.

Pete, S. (2018). Meschachakanis, a coyote narrative: Decolonising higher education. In G. K. Bhambra, D. Gebrial, & K. Nişancıoğlu (Eds.), Decolonising the university, (1st ed., pp. 173–189). Pluto Press.

Peters, M. A. (2018). Why is my curriculum white? A brief genealogy of resistance. In J. Arday, & H. S. Mirza (Eds.), Dismantling race in higher education, (1st ed., pp. 253–270.). Palgrave Macmillan.

Phoenix, A. (2020). ‘When black lives matter all lives will matter’ — A teacher and three students discuss the BLM movement. London Review of Education, 18(3), 519–523. https://doi.org/10.14324/LRE.18.3.14

Quijano, A. (2007). Coloniality and modernity/rationality. Cultural Studies, 21(2/3), 168–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380601164353

Quijano, A. (2000). Power, eurocentrism, and Latin America. Nepantla: Views from South, 1(3), 533–580. https://doi.org/10.1177/0268580900015002005

Schreiber, B., & Yu, D. (2016). Exploring student engagement practices at a South African university: Student engagement as reliable predictor of academic performance. South African Journal of Higher Education, 30(5), 157–175. https://doi.org/10.20853/30-5-593

Schucan Bird, K., & Pitman, L. (2020). How diverse is your reading list? Exploring issues of representation and decolonisation in the UK. Higher Education, 79(5), 903–920. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-00446-9

Shahjahan, R. A., Estera, A. L., Surla, K. L., & Edwards, K. T. (2022). “Decolonizing” curriculum and pedagogy: A comparative review across disciplines and global higher education contexts. Review of Educational Research, 92(1), 73–113. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543211042423

Smith, L. T. (2021). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples. Bloomsbury Publishing.

SOAS. (2018). Decolonising SOAS learning and teaching toolkit for programme and module convenors. London: SOAS. Available at: https://blogs.soas.ac.uk/decolonisingsoas/files/2018/10/Decolonising-SOAS-Learning-and-Teaching-Toolkit-AB.pdf. Accessed 12 Oct 2023

Tuck, E., & Yang, K. W. (2021). Decolonization is not a metaphor. Tabula Rasa, (38), 61–111.https://doi.org/10.25058/20112742.n38.04

UCL. (2018). Inclusive curriculum healthcheck. London, UK: UCL. Available at: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/teaching-learning/sites/teaching_learning/files/ucl_inclusive_curriculum_healthcheck_2018.pdf. Accessed 12 Oct 2023

UN Sustainable Development Group. (2023). Human rights-based approach. universal values principle one: Human rights-based approach. Available at: https://unsdg.un.org/2030-agenda/universal-values/human-rights-based-approach#:~:text=HRBA%20requires%20human%20rights%20principles,holders'%20to%20claim%20their%20rights. Accessed 9 Oct 2023

University of Brighton. (2019). Decolonising the curriculum: Teaching and learning about race equality. Available at: https://research.brighton.ac.uk/en/publications/decolonising-the-curriculum-teaching-and-learning-about-race-equa. Accessed 9 Oct 2023

Von Bismarck, H. (2012). Defining decolonization. The British Scholar Society, 27-28. https://www.helenevonbismarck.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Defining-Decolonization.pdf

Wawrzynski, M. R., & Garton, P. (2023). Language and the cocurriculum: The need for decolonizing out-of-classroom experiences. Higher Education, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-023-01016-w

Wong, S., Plowman, T., Nwibe, I., Hope, C., & Puri, D. (2020) decolonising-the-medical-curriculum-reading-list-2020. Retrieved May 3, 2023. From. https://decolonisingthemedicalcurriculum.wordpress.com/dtmc-reading-list/. Accessed 20 May 2022

Zembylas, M. (2018). Affect, race, and white discomfort in schooling: Decolonial strategies for ‘pedagogies of discomfort.’ Ethics and Education, 13(1), 86–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449642.2018.1428714

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the course participants for sharing their insights, experience, and valuable feedback on the course. We thank scholars who taught on the course; the research assistants who worked on the gap analysis, the pilot course, the symposium and the online Archive, all our interviewees, Prof. Hanna Kienzler for guiding our initiatives and her feedback on the article, and our Head of Department, prof. Anne Pollock, for supporting our initiatives.

Funding

Funding was received from King’s College London via

1. The Global Health and Social Medicine Department to conduct the gap analysis

2. The Faculty Education Fund 2022 for piloting a certificate course on ‘Decolonising Research Methods in Global Health and Social Medicine’.

3. Race Equity and Inclusive Education Fund (REIEF) Education and Students 2022 to conduct the gap analysis, the interviews, and focus group.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical standards

Ethical approval was obtained through KCL minimal risk process: Project ID: 28355.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Disclaimer

The funders have no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis and interpretation of data, and in writing the manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tamimi, N., Khalawi, H., Jallow, M.A. et al. Towards decolonising higher education: a case study from a UK university. High Educ (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-023-01144-3

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-023-01144-3