Abstract

The article examines how higher education institutions respond to ambiguous governance instruments. A key focus is how ambiguity is tackled in the interpretation and implementation processes. Building on theoretical perspectives from institutional analysis of organisations, an empirical point of departure is the analysis of ten higher education institutions in Norway and their response on the introduction of development agreements. The findings point out two important dimensions in analysing implementation processes: focusing on the change dynamics and the degree of internal integration. In combination, these point towards distinct patterns in organisational responses to ambiguous policy instruments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As many other public organisations, higher education institutions (HEI) in many countries are facing increasingly unstable environments with more frequent changes in governance arrangements. Several studies show that during the last thirty or so decades, governance of higher education has been fundamentally transformed (Ferlie et al., 2008; Musselin, 2021), and nation states put considerable effort into finding effective approaches to steering the sector. More recently, there is also an increasing acknowledgement that the one-size-fits-all funding and steering approaches that emphasise competition as a means to create diversity do not sufficiently cater for the desired differentiation and diversity in higher education systems (Meek, 1991; Sivertsen, 2023). As a solution, a number of different initiatives have been tested, including both new types of governance instruments that emphasise differentiation and dialogue, and policy development processes that involve the sector and stakeholders (Elken, 2023). While stakeholder involvement and dialogue represent a means to manage more specialised and complex knowledge in governance processes (Ansell & Gash, 2008), it may also increase ambiguity of governance arrangements (Elken, 2023), as different stakeholders may think differently about the instrument (Fowler, 2021). Potential cost and pitfalls of ambiguity of instruments are well documented, but ambiguity may also be strategically beneficial to public organisations (Davis & Stazyk, 2014), as it allows flexibility to adapt the governance instrument to often complex, volatile, and uncertain circumstances at the institutional level (Fowler, 2021; Van der Wal, 2017). Yet, what does increased ambiguity of governance instruments mean for implementation processes?

Implementation analysis has in studies of higher education been labelled as the “missing link” in analysis of higher education policy (Gornitzka et al., 2005). In broad terms, one can distinguish between top-down and bottom-up approaches to analysing policy implementation (Sabatier, 1986) — where the former emphasises consistency between policy goals and implementation processes, and latter tend to emphasise the importance of contextual flexibility on a micro level for implementation processes (Matland, 1995). Policy processes include inherent ambiguity — and the commonplace wisdom is that implemented policies in most instances differ from the adopted policies (Eaton Baier et al., 1986). In other words, implementation is inherently “an exercise in coping with ambiguity” (Fowler, 2021), and different degrees of ambiguity lead to different implementation processes (Matland, 1995). While some of these studies would emphasise degrees of ambiguity as an important determining factor, questions can be raised about the variation concerning implementation processes where we can in the outset identify considerable ambiguity.

This article takes a predominantly bottom-up approach and investigates how higher education institutions manage this ambiguity through an analysis of the implementation of performance contracts as a steering instrument in Norway. With this in mind, the research question for the article is: how do organisations respond to ambiguous steering instruments?

Performance contracts have been introduced as a means to develop more effective and diversified steering practices. Countries like the Netherlands, Denmark, Ireland, Scotland, and Canada have been experimenting with various contractual arrangements in the last two decades (Benneworth et al., 2011; De Boer et al., 2015). Contracts represent a formalised agreement between individual institutions and authorities, stipulating pre-determined goals to be achieved over a specified period of time. They have been employed as a governance tool across with emphasis on quality, effectiveness, dialogue, accountability, and profiling (De Boer et al., 2015). A specific element in Norway was that the higher education institutions were invited to be involved in the design and development of both the contracts as a policy instrument and the specific goals within various contracts adding ambiguity to the instrument (Elken, 2023; Elken & Borlaug, 2020). As such, the contracts represent a governance instrument which not only can result in unintended outcomes, but the development process seemed to incorporate and assume potentially ambiguous interpretations.

To analyse the policy implementation, we employ a bottom-up approach (Gornitzka et al., 2005), where we draw upon insights from organisational institutionalism on organisational responses to uncertainty and ambiguity in their environment, adapt such insights to the changing governance context, and have iteratively worked with empirical data. The empirical data underpinning this work consists of interviews and document sources. In the next sections, we first contextualise the study in the changing governance patterns, then provide the analytical framing of the paper building upon organisational theory, after which we give a description of methodology and empirical context for the analysis. We then present our results categorised into specific patterns of change in our empirical case, and identify specific dimensions that may be relevant for analysis of implementation processes in higher education more generally.

Performance contracts and changing approaches to governaning higher education

Organisational behaviour of HEI takes place in a specific governance context which has strengthened organisational aspects (Ramirez, 2010). During the last two-three decades, reforms in European higher education have emphasised deregulation, new steering modes, and increased autonomy (Shattock, 2014). This has been accompanied by stronger accountability mechanisms and emphasis on performance measures in both steering structures and funding mechanisms (Hicks, 2012; Ramirez, 2010). Yet, since the turn of the millennium, there has also been a new shift, and the change assumptions in public sector have transformed as deregulation and market dependence have not delivered (Peters, 2001). Contemporary steering ideas are thus marked by a sense of duality — on the one hand, there have been reforms emphasising institutional autonomy and de-regulation; on the other hand, in many countries, the state has re-entered as a more active player. Rather than merely being engaged in setting general targets, a stronger emphasis on bilateral dialogue emerges. System differentiation is in this context a desired goal.

In systems with strong state control, differentiation was initially the result of centralised planning, by assigning different tasks to different institutions (Clark, 1983). In the context of deregulation, the expectation is that institutions themselves would develop unique profiles (Enders & de Boer, 2009). Yet, institutional pressures can instead result in “academic drift” where institutions end up becoming more similar (Teichler, 2006). This is strengthened by funding systems that create incentives for institutions to compete for the same funding (Whitley et al., 2010), following the same criteria for performance and excellence. As a result, some governments have taken more active measures to steer institutional profiles (Laudel & Weyer, 2014). This does not mean a simple return to state control. Instead, several countries in Europe have been experimenting with various forms of contractual arrangements between the state and individual institutions (Benneworth et al., 2011; De Boer et al., 2015; Gornitzka et al., 2004; Jongbloed & de Boer, 2020). The design of agreements plays an important role for their potential impact (De Boer et al., 2015; Jongbloed & de Boer, 2020).

A key characteristic of performance contracts is that the measures of goal achievement may be both summative and formative. The hitherto regime of performance indicators has primarily emphasised summative evaluations of performance. Such forms of assessments are used by some agreements. However, performance agreements also include an opportunity to shift attention to formative evaluations and can thus also include goals that focus on processes or efforts. This is referred to as the difference between hard and soft contracts (De Boer et al., 2015). Moreover, performance contracts may also involve the sector in target-setting, inviting for a more participatory and dialogue-oriented governance. Altogether one could argue that these elements can also strengthen ambiguity — e.g. in terms of performance evaluation and multiple interpretations among different actors.

Analytical framing of organisational responses to policy initiatives

Our starting point to analysis of policy implementation is in a bottom-up perspective where specific contextual and organisational characteristics become emphasised. Specific policy and governance initiatives are usually aimed at introducing some kind of change within the organisation. Higher education institutions are highly institutionalised organisations where introducing both fundamental and rapid change may be challenging. Policies represent a specific kind of change pressure. These are environmental demands that organisations usually cannot completely ignore. Such initiatives also represent environmental demands that are not necessarily institutional in nature, as would for example be the case in the widely used model by Oliver, (1991), who conceptualised responses to institutional pressures towards conformity. In the following, we outline different possible theoretical paths for understanding change processes.

We build on two main sets of arguments concerning how organisations may respond to complex and unclear policy expectations. A simple explanation would be that organisations respond to policies simply by adopting them in some manner. Yet, this adoption can lead to different outcomes, depending on the scope of change proposed. If there is a high level of complementarity, this essentially results in limited changes (Greenwood et al., 2011); in other words, if the organisations already do what they perceive the policy initiative to bring about, not much changes. This may for example take place when some types of changes are unevenly present in the system and it is desirable to facilitate such changes in the whole sector, or, when formal policy “catches up” with developments within the sector. While this may indeed be the case in some instances, we may expect that often, the purpose of policy initiatives is to bring about some kind of change.

When policy initiatives are expected to bring about change, two distinct patterns can be outlined. First, limited complementarity between external demands and existing internal situation may result in decoupling (and potentially recoupling) processes (Bromley & Powell, 2012). Second, organisations may also respond to unclear demands from the environment by aiming to translate the external demands to fit their internal processes (Czarniawska & Joergers, 1996).

In our first line of reasoning, institutional analysis of organisations, by for example Meyer & Rowan, (1977), emphasises how environmental demands lead to construction of formal structures, and how these may become decoupled from work processes within organisations. A key driver for organisations to adapt to such demands is to maintain legitimacy, to showcase to both internal and external actors that the organisation is responding “adequately” and “properly,” which in turn can reduce potential turbulence (ibid). As demands multiply and complexity increases, adopting them may not always be straight forward. A core to Meyer and Rowans argument then is that in order to manage the contradictions that emerge, organisations can engage in decoupling between formal structure and work processes (ibid). Essentially, this is a form of window dressing concerning implementation process. It is this decoupling process that can explain persistent variation in implementation processes. In more recent literature, this form of decoupling is also referred to as decoupling between policy and practice, or as symbolic adoption (Bromley et al., 2012; Bromley & Powell, 2012). It is likely to take place when adoption is motivated by legitimacy and there is weak internal reinforcement. The latter may be a result of a poor fit between external demands and internal priorities, goals, and identities; lack of external reinforcement; and internal constituents who have sufficient power to reject external pressures (Bromley & Powell, 2012). For analysis of policy implementation, we can expect that a policy initiative would not be the first of its kind, and as a result, any policy initiative meets organisational complexity by default. We can also expect that for many higher education institutions, there are incentives to (at least seem to) “behave properly” in relation to specific policy initiatives even if these are unclear, whether implicitly as this is proper behaviour (for public institutions), or to avoid sanctions if these are present. This does not mean that decoupling would be a permanent state of affairs; organisations can over time engage in “re-coupling” external demands to internal practices (Hallett, 2010). This is particularly decisive when the sheer scope of external demands is extensive or shifting, and meanings may have to be renegotiated. When policy initiatives are unclear, this can also open for an opportunity to renegotiate meaning.

Our second line of reasoning builds on the notion of translation, that is how ideas circulate and their organisational consequences (Czarniawska & Joergers, 1996). While much of the research has focused on the concept of imitation and why particular organisations may pick up specific ideas (Sahlin & Wedlin, 2013), this set of literature also provides a line of argumentation for understanding how external pressures/demands become edited and translated in the adoption process. A key argument is that by adopting new external demands, these would over time matter for organisational processes, but that the external demands themselves also become transformed in the process. The main emphasis is on imitation within fields where circulation and adoption of external impulses (“ideas”) are driven by a desire to emulate successful organisations. As Sahlin & Wedlin, (2013) argue, in the first step, the presentation of changes follows existing frames and classifications. As these likely vary in different institutions, the recontextualisation that takes place varies. This is referred to as “editing” — when both the content and the formulation can become altered. Also here, we can find arguments to how organisations may respond to unclear policy initiatives: different organisations represent different contexts, leading to differentiated responses and varied speed in implementation processes. Those organisations being first to implement certain measures may also influence implementation in subsequent organisations. This means that when initiatives are unclear at the outset, early implementers are given considerable leeway to shape them.

Based on these arguments, one can identify two key dimensions as the conceptual underpinning. First, the two main lines of reasoning provided above represent a continuum of varying degrees of changes within organisations as a result of external demands — in other words, the degree of change proposed by the policy initiative matters. Second, they also represent a continuum of varying degrees of shaping and editing the demands in the process of implementation.

Research context and data sources

Research context: introduction of performance contracts in Norway

Higher education in Norway consists of a predominantly public system of universities and university colleges. While the sector is formally still a binary system, both types of institutions are governed by the same legal act, and are a subject to similar governing approach by the ministry. Consolidation and differentiation of the higher education system as overarching themes have been a policy concern for several decades (Chou et al., 2023; Sivertsen, 2023). Since the 1990s, there have been two waves of mergers (in 1994 and from 2015 and onwards), and considerable academic drift has been present in the sector (Kyvik, 2002; Vukasovic et al., 2021). Governance of HEI in Norway is marked by a dual dynamics — while reforms enhance stronger formal autonomy, strong focus on accountability and evaluations also suggests considerable capacity for state control (Maassen et al., 2011).

In 2015, a public committee examining the funding system suggested to consider performance contracts as a means to introduce more differentiated funding system (Hægeland et al., 2015). Performance contracts (development agreements) were introduced as a pilot scheme from 2016 and extended to the whole sector. At the time, the Norwegian higher education sector included in 21 publicly owned institutions. In the first round of piloting in 2016, five higher education institutions were included, covering large and old universities, smaller universities, and smaller regional university colleges. The mixture was intended to obtain a diverse sample of piloting institutions. This was also the case for the five institutions included in the second round in 2017. The remaining 11 developed their agreements in 2018. In 2022, the agreements were renegotiated as a part of a wider restructuring of the steering system. Participation in the two pilots was voluntary, and the institutions who did also had expectations of providing input to the further process. Development of the individual agreements took about a year — through both bilateral discussions and plenary discussions. After the pilot, institutions have expressed that they have experienced autonomy in the process (Lackner, 2023). In the pilot version, the ministry also suggested some goals in politically important areas. The decision on whether to attach funding to the contracts remained undecided during the pilot, creating uncertainty.

Stated key purposes included quality and differentiation, profiles, and division of labour, as well as strategic support for the leadership. Still, the agreements were perceived rather differently in the sector, being an indication of their ambiguity. This was mainly the result of the very open process introduced by the ministry which in essence let institutions largely define themselves (within some very broad boundaries) not only how to implement the agreements (which was expected to be the jurisdiction of institutions) but also to define what kind of instrument this is (Elken, 2023). This resulted in multiple interpretations within the sector which is a starting point of the analysis in this article, and this will be followed up in our “Findings” section.

Data and methodology

To investigate how the piloting institutions responded to the instrument, we applied an abductive approach which builds on the premise of a cultivation of surprising empirical finding against a background of existing theories (Timmermans & Tavory, 2012). A theory informed qualitative approach based on document analysis and interviews allowed us to gain an in-depth account of different perspectives on and responses to the agreements as a steering instrument.

The data collection was carried out in spring/summer 2020. A total of 56 qualitative interviews with key informants were conducted. Of these, 48 interviews were carried out in the ten institutions who were part of the two first round of pilots of introducing the contracts, with four to six interviews per institution. The informants were purposefully selected key decision-makers, including mostly representatives for top leadership at these institutions, institutional boards (leaders/members), and some leaders on other levels (e.g. project/faculty) where this was relevant due to specific circumstances (e.g. specific priorities in the contracts). The interviews took up themes concerning the purposes, aims and form of agreements, their relationship to other steering instruments, and how the agreements had been taken up on institutional level. An additional eight interviews with similar themes (excluding organisational responses) were conducted at the ministry, including leadership and bureaucracy.

All interviews were transcribed and coded (NVivo) as thematic analysis. We first identified descriptions concerning the various elements of the process of introducing agreements in the system and on institutional level, and identified emerging explanatory factors from interviews that could explain different kinds of processes. Main overarching coding categories were as follows: Dialogue and contact with the ministry; the introduction of the agreement within the HEIs; the relation between the agreements, strategy, and other steering instruments; internal reactions and how the agreements were followed-up; goals, parameters, indicators, and the need for developing new types of data/information; reporting; perceived effects on diversification and differentiation; perceived effects on governance and steering and perceived effects on profiling.

We further coded central documents. For the institutions, these included the agreements themselves, but also strategy documents on institutional level and other documentation about implementation where this existed. These were primarily used to establish a timeline of events and the match between goals in the contracts and those in existing strategic documents.

Based on the analysis of the interviews and the documents, we developed two sets of thick descriptions. First, we produced an elaborate outline of the process on the system level. Second, we developed a case report for all ten institutions we examined. The case report included basic organisational description, their input to the national process, and a description of the local implementation process. Our analysis here primarily builds on the segments on local implementation, while the national developments are used as background data.

Through these two stages of analysing the data, distinct patterns of change were identified. Notably, this was an iterative process going back to the theory and confronting it with our empirical material (Timmermans & Tavory, 2012). We observed in this process that the HEIs in our empirical material responded and translated the agreement in different and sometimes unexpected ways, which further generated a need for developing new analytical constructs.

This methodological and analytical approach has some limitations. First, we have only interviewed the top leadership at the institutions, including the board of governors, and thus, we omitted the perspectives of staff and potential further implications or lack of implications of the agreements at lower levels which may have given additional insights. Second, we have collected data in ten institutions, who were the early adopters. However, these were also the institutions that met the greatest degree of ambiguity concerning the instrument (Elken & Borlaug, 2020).

In the following we will first, based on our analysis, describe four key aspects which we found decisive for the process of implementing the agreements. Thereafter, we outline four distinct patterns of responses to the development agreements as a steering instrument.

Findings

Key aspects decisive for the implementation process

In the iterative process of analysing the data, four key aspects were found decisive for how the agreements were interpreted and implemented within the institutions.

First, there were high levels of variation in how the interviewees, both in the ministry and at the institutions, perceived the purpose of the agreements. This offered the opportunity for action and for translating and editing the role and strength of the agreements as well as different parts of the agreements towards certain needs, especially by the leadership at the institutions. Hence, the perceptions of the role and purpose of the agreements became important for how they were implemented at the institution.

The second aspect was the design of the goals in the agreements and the extent to which they were characterised by being summative- and/or process-oriented. Institutions had developed reasonably different interpretations of appropriate goals. Data indicated that process-oriented goals have larger impact on the translation process as they require more editing compared to summative goals that are more easily retrieved among existing indicators in the sector.

A third aspect was who defines the goals of the agreement. Institutions had limited ownership over the goals that were imposed/suggested by the ministry. This resulted in reduced legitimacy of the agreements. At institutions where there was a perceived lack of ownership to the goals, there were fewer attempts for more in-depth translation and integration, and the agreements had a limited impact on the overall steering within the institutions.

Here, the fourth aspect — the role of leadership of the institution also played a crucial role. If leaders remained protective and buffered the agreements, this also limited the potential of the agreements and their perceived legitimacy. One of the selling points from the ministry had been that the agreements could function internally as support to leadership at the institutions, and from our analysis, it became clear that leaders had a substantial role in bringing this forward within the organisation and being facilitators for more integrative approaches with more substantive translation to local context.

The emphasis of these four aspects varied across the institutions which contributed to considerable heterogeneity in how the agreements were implemented.

Approaches to respond to development agreements

Based on the above and our analytical starting point, we have distilled the different observed changes into four implementation patterns. Practices of both decoupling and translation could be observed. Not only did the institutions have different responses to the agreements, but on occasion different parts of the agreements were followed up differently. Hence, the proposed patterns of change do not represent one institution. Rather, all our ten cases were a hybrid of two or more of the change patterns outlined below, but most had their primary emphasis on one of the them. Building on our theoretical starting point, the patterns cover the degree of change introduced in implementation and degrees of local translation. We have further refined these into two key dimensions: First, whether the new instrument created frictions when meeting existing local circumstances, in this manner representing a challenge to existing normative templates, or whether the instrument fit into existing frame of reference. In essence, this concerns also the degree of conflict and contestation in implementation (see, e.g. Matland, 1995). Second, the extent to which the local implementation process involved translation to a local context and an attempt to integrate this new set of goals into existing goal structure. It is particularly the integrative attempts that seemed to matter.

Avoiding frictions by sticking to what is there, but no integrative attempts

In many of the institutions, the agreements were perceived to have limited internal consequences. This was not because of strategic avoidance, it was merely perceived that the agreements brought nothing new, so the impression was that the institutions were already doing what the agreements were demanding, representing a form of implementation where attempted change was largely buffered. This was either the result of the goals of the agreements overlapping very strongly with existing institutional goals or goals stipulated in other parts of the steering system. As described by one interviewee:

This is what makes it challenging, it is a too large overlap, and it is therefore not appropriate to operate with different steering systems – we have development agreements, the national steering goals, our strategy and the operationalisation of this in terms of plans of action on different areas and within different faculties, and so on… (leadership)

Some informants reported that the overlap of goals was intended as it gave the impression of integration, which was the way to manage uncertainty. The result in practice, however, was that the agreements instead ended up having limited impact and added value for the institutions. As described by another leadership representative: “Why should we have an additional document called development agreement, it should be sufficient with the strategy.”

Looking into the agreements in such instances, the goals were rather generic and thus poorly integrated to local steering priorities. One example was the aim to “enhance the amount of external research funding.” This is a continuous goal for all institutions and was already incentivised in the performance-based funding of institutions. As such, the goal does not represent any challenge to existing goal structures or priorities. These types of goals as well as indicators for following up were rather common, and we observed that nearly all institutions had included formulations like this, but some considerably more than others. Generic goals in such agreements would to a limited extent contribute to differentiation and diversification in the higher education system. The goals were also often summative and not process-oriented. They did not challenge existing priorities within the organisation and thus created little friction.

In some of the cases, this form of response was associated with change only being symbolic, while others also viewed this as being a case of slow adoption, opening up to attempts for more integration at a later stage.

In terms of indicators, this is a matter of maturation, I think. We started the work. We have a development agreement, we thought we had the right areas, but now we see that for the agreement to mean something in the organisation, they [the indicators] need to be not so spineless, that is, they must be more operationalised and integrated into the existing goal hierarchy. (leadership)

For the time being, implementation is viewed as a limited change and further work with integration was viewed as unnecessary. This suggests that while high degree of complementarity could be seen to imply limited changes (Greenwood et al., 2011), lack of explicit integrative attempts can nevertheless create gaps and problems.

Agreements as a new set of goals, disconnected from other goals

The agreements in some institutions did bring in new goals and priorities but remained isolated from the organisation’s strategic processes, following the traditional argument of decoupling. Changes were primarily implemented to assure legitimacy on a national arena. Goals formulated by the ministry to which the institutions had limited ownership are one typical example here. The goals became a new layer, resulting in added complexity locally. If integrative attempts were not made, there was limited prioritisation, and internal goal structure became overwhelming. As one leader noted: “We cannot see the wood for the trees.” Informants further described how there were too many goals and a need to report to different stakeholders.

A result of this was limited linkages between the contracts and local strategic work. It was primarily the administrative staff that got the responsibility for reporting as part of the institution’s annual reporting. The lack of integration into the existing local steering led to a limited impact of the agreement as a steering instrument within the institution, both in terms of strategic and operative steering. One leader illustrated this: “So, I feel to a large extent, that what we do now is only an administrative exercise. We report on the development agreement in the annual reporting […] it does not get a lot of attention from the leadership.” As the agreements became an administrative matter, limited local translation took place.

This disconnection was also related to the leadership views on the potentials of the agreement for steering. One leader also expressed a worry for the institutions’ autonomy:

…and this is what is problematic, it is the institutions autonomy. It is ok that we have to report to our owner, and it is ok with a dialogue. But the universities are by law autonomous and have academic freedom within the laws and economic frames and if we get too many of these types of extra steering mechanisms, it will be perceived as a retrenchment of the autonomy.

The emphasis on both autonomy and that the strategy is a sufficient steering instrument, limited the perceptions of the agreement as an instrument for internal steering, and further contributed to a decoupling strategy.

Agreements as a way to prioritise within existing goal structure

Moving towards more integrative attempts, some institutions to a larger extent translated and integrated the agreements into their local processes. Here, the agreements had primarily a local strategic role, to focus some aspects of the strategy. This did not mean the agreements were always visible locally, but leadership saw this as an opportunity to set direction in their dialogue with for example institutional boards. While strategies have a long-time horizon and overarching nature, the agreement had more short-term and specific goals to deliver upon, the informants claimed. For some, it was also important to underline that this was an agreement between the institution and the ministry, to add power to the role of the agreements within the institution. As such, the agreement amplified the institution’s strategy and gave the leadership a legitimacy to act as it served as a prioritisation mechanism. As described by one of the leaders: “I think the most important is that we use this to strengthen or develop the existing steering and strategy work. It creates an extra pressure within the organisation to set the direction the way we think is important.” Another leader also supported and emphasised the agreement’s role as a prioritisation device and as a means to amplify the effect of their own strategy: “It is a bit like, sure.., strategy, what is that really about.. it is easier for us to say that we have an agreement with the ministry, we will be measured on this, so this we have to deliver on. Incentives and goals, they have an effect, people comply with them. So, the agreement will reinforce our own strategy.” Visible in both of these quotes is that the contracts were more integrated to local circumstances and had undergone some degree of editing. Yet, they also illustrate that the contracts did not challenge existing normative templates; they assisted with prioritisation within existing set of goals and priorities.

The agreements could also function as a mechanism for simplifying the work of institutional boards, as some board members embraced the agreements and saw them as a focusing tool. One board member noted that: “When we discussed strategic matters, we hooked them onto the agreements.” The agreements further served as a mechanism for understanding the importance of strategy and creating cohesion within the board, described by another board member: “The agreement strengthens the opportunity to get an understanding of strategic leadership, and that we are a team, we [the board] get a greater team spirit”

While few, there were also examples where the agreements were followed up with organisational infrastructure and re-allocation of funding because of prioritisations. One example was the establishment of an internal project on digitalisation. In these instances, there was a tight coupling between the strategy and the agreements where the latter was used to set the strategy into action.

Agreements as a steering template

In the most integrated version, the agreements represented a new way to think about local steering, and there were active steps to integrate the changes. Not only did the agreements have an impact in terms of priorities, leadership also used them to transform internal steering practice. While most institutions in Norway operate with internal goal management systems (Frølich, 2005), there is variety in how this is practiced. In instances where a generic annual plan was perceived inappropriate, the principal idea of agreements was copied internally. The change put more emphasis on bilateral dialogue between institutional leadership and the faculties, and allowed for different of goals between faculties. Many of the goals were process-oriented, allowing for setting some directions. One leader explained: “The document lays the foundation for a long-term dialogue on development goals with each of the faculties.” These localdevelopment plans were not unequivocally accepted in the organisation and created some tensions as they represented a new internal steering instrument. This was explained by one informant as: “As between the university and the ministry, we [the faculty] may use the development plan to tighten the screw a bit extra on matters we would like to work on more systematically. It has to relate to the annual plans and strategy, of course, but it may function as a disciplinary mechanism in certain environments, we emphasise that this is in a plan developed together with the rectorate.” Another leader claimed: “So, now the faculties have a ‘ghost’ hanging over their head which they may use in their dialogue with their departments.” This basically suggests the departments could also strategically reinforce their own priorities by referring to leadership, similar to the arguments that the ministry had used when introducing the contracts nationally. An element of this was the worry that the agreements could lead to stronger internal steering, emphasised by some of the informants. Nevertheless, this form of local implementation suggested that the agreements were thus no longer only an external structural demand but also a normative template for “good steering” internally at the institution.

Summing up

These four patterns of implementing the agreements indicate that the four key aspects vary on a range from low to high. For instance, limited integrative attempts implied summative goals (low on process-oriented), low degree of ownership over the goals and perceiving the role of the agreements in steering of the institution as low alongside leadership not using the agreement. On the reverse side, where the agreements were used as a steering template, these four aspects are all characterised by being highly present.

Discussion

From our analysis of the implementation of development agreements, we can relate these to our central conceptions concerning scope of change. The first concerned that the agreements in principle supplemented the existing performance-based and steering system, thus not representing change as such. The other concerned the view that the agreements did bring something new on the table and the institutions could use them to act strategically both internally and externally. Where the former would imply that the agreements did not challenge existing normative templates within the organisations, the latter represented a challenge.

These two conceptions co-existed in the system and resulted in different ways in which the agreements were coupled with internal steering mechanisms. Here, ambiguity was feeding into these parallel conceptions, as it allowed both interpretations to prevail (cf. Fowler, 2021). One question remaining is whether agreements were perceived as not bringing in anything new because they were perceived as illegitimate, or vice versa. Nevertheless, these co-existing conceptions allow us to engage in some more general reflections about implementation patterns.

Overall, we observed that there has been an uptake of the steering instrument, but this varied, and there was considerable variation in how the instrument was integrated within the organisation. Only a small number of the institutions among our ten actively engaged in decoupling as their primary response. However, it was also obvious that when the agreements served as a focusing or strategising tool for leadership priorities, and the content of the agreement was perceived as legitimate by leadership, the types of goals were also more process-oriented.

The analysis reveals that when responding to such instruments as change drivers, we can further refine our analytical starting point. Our starting point here was that in most public systems of higher education, institutions usually need to comply with public policy initiatives (or at least seem to do so). While our starting expectations put focus on the scope of change, our data indicates that it also concerns the degree to which the introduced change operates within existing normative templates, i.e. whether the proposed change operates within existing ways of doing things or whether the proposed change represents a more fundamental challenge potentially introducing frictions into the organisation (cf. Greenwood et al., 2011). In other words, this concerns the extent to which instruments bring in new impulses that challenge current organisational practices, priorities and ways of doing things, or not. One could expect that ambiguity would mean that decoupling would emerge, but our data also suggests that it can be related to different translations.

The other dimension we initially focused on translation, can further be refined as integration, that is, whether the instruments are implemented in isolation in a manner where it remains decoupled from other internal processes, or whether there is an attempt to also integrate them into the overall governing practice of the institution — either as a tool to prioritise, or as a template for steering practice.

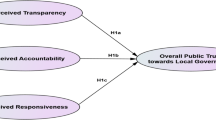

Based on those two dimensions, we can identify four patterns of implementation.

We have labelled the first pattern “buffered implementation” (Fig. 1). Here, the implementation processes are marked by an instrumental compliance-oriented logic, where ambiguity in this instance can create uncertainty. A means to comply is to make sure the proposed instrument wont challenge status quo at all. While the strategy allows for a way to buffer undesirable changes, it will over time increase complexity when demands multiply and compliance remains necessary. In contrast, in situations where new normative templates are at play, one can expect decoupling to emerge to a larger extent, into what we label as “symbolic implementation.” Ambiguity can be expected to enhance the need to “box in” the implementation process locally and engaging in window dressing.

On the integrative side, the first pattern we have labelled as “integrative implementation.” Here, instruments would be integrated locally — yet the integration would remain within existing normative templates. While it could be the case that priorities are made, there is no substantive challenge to existing priorities and practices and a need to renegotiate meanings. Finally, when implementation both challenges existing status quo in a substantive manner and is focused on integration, we can observe “interpretive implementation,” where ambiguity allows for local interpretation and translation processes.

It should be mentioned that the heuristic is not normative in nature, where focus on interpretive implementation processes is desirable and buffered implementation is undesirable — different variations can emerge and be necessary depending on circumstances. The empirical case here also provided some possible insights into what matters for the various patterns identified here. For example, acknowledgement of internal complexity over simplistic assumptions, leadership engagement, and local ownership seem to point towards more integrative approaches. Moreover, a stronger administrative and academic divide is related to less integrative approaches. In contexts where the proposed change is ambiguous, it is nevertheless important to have some clarity over goals, as lack of clarity can also weaken ownership.

Concluding remarks

While literature on higher education is still ripe with analysis of the consequences of new public management and marketisation in governing of higher education, the policy trajectories in Europe are mixed (Maassen et al., 2011), and also include an increased focus on re-regulation (Capano & Pritoni, 2020). Recent shifts in analysis of public governance also hint of possible changes that may become more relevant for higher education over time. For example, research on collaborative governance (Ansell & Gash, 2008; Ansell & Torfing, 2015; Bingham, 2011) is one avenue where new, more networked, and more participatory forms of governance have become pronounced. Also, in higher education, some of this has started to manifest in Europe. In quality assurance, there is a shift away from hard regulative accreditation-oriented regimes towards more risk-based, dialogue oriented, and differentiated forms of quality assurance (Elken & Stensaker, 2022).

This article provides a starting point to discuss how universities respond to ambiguous governance instruments, and the local implementation processes that emerge. The study adopted a bottom-up approach to implementation. Through a study of how ten higher education institutions implemented the pilot of development agreements in Norway, we identified four implementation patterns — including both decoupling-oriented and translation-oriented approaches. With this as a starting point, the article assumes that ambiguity matters in implementation processes (Fowler, 2021; Matland, 1995), and it can both be a resource in the implementation process, while it also shapes the implementation processes. It is a resource when some leeway concerning various local translations is relevant, but it can also lead to very different local interpretation processes which can undermine implementation processes.

With this in mind, we proposed a heuristic building on two core dimensions — the degree to which changes introduce new normative templates and the degree of integration within the organisation. In each of those, ambiguity plays an integral, but different, role. We hope the heuristic provided in this article can provide one starting point for further discussions and a starting point to explore implementation processes where multiple interpretations are not a finding but a basic expectation of implementation processes.

References

Ansell, C., & Gash, A. (2008). Collaborative governance in theory and practice. Journal of public administration research and theory, 18(4), 543–571.

Ansell, C., & Torfing, J. (2015). How does collaborative governance scale? Policy & Politics, 43(3), 315–329.

Benneworth, P., de Boer, H., Cremonini, L., Jongbloed, B., Leisyte, L., Vossensteyn, H., & De Weert, E. (2011). Quality-related funding, performance agreements and profiling in higher education: An international comparative study. CHEPS.

Bingham, L. B. (2011). Collaborative governance. In M. Bevir (Ed.), The SAGE handbook of governance (pp. 386–401). Sage.

Bromley, P., Hwang, H., & Powell, W. W. (2012). Decoupling revisited: Common pressures, divergent strategies in the US nonprofit sector. M@n@gement, 15(5), 469–501.

Bromley, P., & Powell, W. W. (2012). From smoke and mirrors to walking the talk: Decoupling in the contemporary world. The Academy of Management Annals, 6(1), 483–530.

Capano, G., & Pritoni, A. (2020). What really happens in higher education governance? Trajectories of adopted policy instruments in higher education over time in 16 European countries. Higher Education, 80(5), 989–1010. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00529-y

Chou, M.-H., Elken, M., & Jungblut, J. (2023). Policy framing in higher education in Western Europe: (Some) Uses and (many) promises. In J. Jungblut, M. Maltais, E. Ness, & D. Rexe (Eds.), The politics of HE policy in North America and Western Europe. Springer.

Clark, B. R. (1983). Higher education systems: Academic organization in cross-national perspective. University of California Press.

Czarniawska, B., & Joergers, B. (1996). Travel of Ideas. In B. Czarniawska & G. Sevón (Eds.), Translating organizational change (pp. 13–47). De Gruyter.

Davis, R. S., & Stazyk, E. C. (2014). Developing and testing a new goal taxonomy: Accounting for the complexity of ambiguity and political support. Journal of public administration research and theory, 25(3), 751–775. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muu015

De Boer, H., Jongbloed, B., Benneworth, P., Cremonini, L., Kolster, R., Kottmann, A., et al. (2015). Performance-based funding and performance agreements in fourteen higher education systems. CHEPS.

Eaton Baier, V., March, J. G., & Saetren, H. (1986). Implementation and ambiguity. Scandinavian Journal of Management Studies, 2(3), 197–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/0281-7527(86)90016-2

Elken, M. (2023). Collaborative design of governance instruments in higher education. Studies in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2023.2258905

Elken, M., & Borlaug, S. B. (2020). Utviklingsavtaler i norsk høyere utdanning: En evaluering av pilotordningen. NIFU.

Elken, M., & Stensaker, B. (2023). Bounded innovation or agency drift? Developments in European higher education quality assurance. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 48(3), 321–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2022.2078476

Enders, J., & de Boer, H. (2009). The mission impossible of the European university: Institutional confusion and institutional diversity. In A. Amaral, G. Neave, C. Musselin, & P. Maassen (Eds.), European Integration and the Governance of Higher Education and Research (Vol. 26, pp. 159–178). Springer.

Ferlie, E., Musselin, C., & Andresani, G. (2008). The steering of higher education systems: A public management perspective. Higher Education, 56(3), 325–348. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-008-9125-5

Fowler, L. (2021). How to implement policy: Coping with ambiguity and uncertainty. Public Administration, 99(3), 581–597. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12702

Frølich, N. (2005). Implementation of new public management in Norwegian Universities. European Journal of Education, 40(2), 223–234.

Gornitzka, Å., Kyvik, S., & Stensaker, B. (2005). Implementation analysis in higher education. In Å. Gornitzka, M. Kogan, & A. Amaral (Eds.), Reform and change in higher education: Analysing policy implementation (pp. 35–56). Springer.

Gornitzka, Å., Stensaker, B., Smeby, J. C., & De Boer, H. (2004). Contract arrangements in the Nordic countries—Solving the efficiency/effectiveness dilemma? Higher Education in Europe, 29(1), 87–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/03797720410001673319

Greenwood, R., Raynard, M., Kodeih, F., Micelotta, E. R., & Lounsbury, M. (2011). Institutional complexity and organizational responses. The Academy of Management Annals, 5(1), 317–371.

Hallett, T. (2010). The myth incarnate: Recoupling processes, turmoil, and inhabited institutions in an urban elementary school. American Sociological Review, 75(1), 52–74.

Hicks, D. (2012). Performance-based university research funding systems. Research Policy, 41(2), 251–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2011.09.007

Hægeland, T., Ervik, A. O., Hansen, H. F., Hervik, A., Lommerud, K. E., Ringdal, O., ... Stensaker, B. (2015). Finansiering for kvalitet, mangfold og samspill - Nytt finansieringssystem for universiteter og høyskoler. Ministry of Education and Research. Available at: https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/0d3aa576467f4eeeb7f7af25a26d607a/finansieringuh_rapport.pdf

Jongbloed, B., & de Boer, H. (2020). Performance agreements in Denmark, Ontario and the Netherlands. University of Twente, CHEPS.

Kyvik, S. (2002). The merger of non-university colleges in Norway. Higher Education, 44(1), 53–72.

Lackner, E. J. (2023). Agreements between the state and higher education institutions – How do they matter for institutional autonomy? Studies in Higher Education, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2023.2258901

Laudel, G., & Weyer, E. (2014). Where have all the scientists gone? Building research profiles at Dutch universities and its consequences for research. In Organizational transformation and scientific change: The impact of institutional restructuring on universities and intellectual innovation. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Matland, R. E. (1995). Synthesizing the implementation literature: The ambiguity-conflict model of policy implementation. Journal of public administration research and theory, 5(2), 145–174. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a037242

Meek, V. L. (1991). The transformation of Australian higher education from binary to unitary system. Higher Education, 21(4), 461–494. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00134985

Meyer, J. W., & Rowan, B. (1977). Institutional organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. American journal of sociology, 83, 340–363.

Musselin, C. (2021). University governance in meso and macro perspectives. Annual review of sociology, 47, 305–325.

Maassen, P., Moen, E., & Stensaker, B. (2011). Reforming higher education in the Netherlands and Norway: The role of the state and national modes of governance. Policy Studies, 32(5), 479–495. https://doi.org/10.1080/01442872.2011.566721

Oliver, C. (1991). Strategic responses to institutional processes. The Academy of Management Review, 16(1), 145–179 Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/258610

Peters, B. G. (2001). The future of governing: Four emerging models (2nd, rev. ed.). University Press of Kansas.

Ramirez, F. (2010). Accounting for excellence: Transforming universities into organizational actors. In V. Rust, L. Portnoi, & S. Bagely (Eds.), Higher education, policy, and the global competition phenomenon. Palgrave Macmillan.

Sabatier, P. A. (1986). Top-down and bottom-up approaches to implementation research: A critical analysis and suggested synthesis. Journal of Public Policy, 6(1), 21–48.

Sahlin, K., & Wedlin, L. (2013). Circulating ideas: Imitation, translation and editing. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, K. Sahlin, & R. Suddaby (Eds.), The SAGE handbook in organizational institutionalism (pp. 218–242). SAGE.

Shattock, M. (Ed.). (2014). International trends in university governance. Autonomy, self-government and the distribution of authority. Routledge.

Sivertsen, G. (2023). Performance-based research funding and its impacts on research organizations. In B. Lepori, B. Jongbloed, & D. Hicks (Eds.), Handbook of Public Funding of Research (pp. 90–106). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Teichler, U. (2006). Changing structures of the higher education systems: The increasing complexity of underlying forces. Higher Education Policy, 19(4), 447–461. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.hep.8300133

Timmermans, S., & Tavory, I. (2012). Theory construction in qualitative research: From grounded theory to abductive analysis. Sociological Theory, 30(3), 167–186.

Van der Wal, Z. (2017). The 21st century public manager. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Vukasovic, M., Frølich, N., Bleiklie, I., Elken, M., & Michelsen, S. (2021). Policy processes shaping the Norwegian Structural Reform. NIFU.

Whitley, R., Gläser, J., & Engwall, L. (2010) Reconfiguring knowledge production: Changing authority relationships in the sciences and their consequences for intellectual innovation, Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199590193.001.0001

Funding

The empirical data collection for this project was conducted in the framework of an evaluation of the pilot scheme, funded by the Ministry of Education and Research in Norway. The research was carried out autonomously and independently.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Elken, M., Borlaug, S.B. Implementation of ambiguous governance instruments in higher education. High Educ (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-023-01161-2

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-023-01161-2