Abstract

The Netherlands reformed its disability insurance (DI) scheme in 2006. Reintegration incentives for employers became stronger, access to DI benefits became more difficult, and benefits became less generous. Using administrative data on all individuals who fell sick shortly before and after the reform, we study the impact of the reform on labor participation of individuals who fell sick and their spouses. Difference-in-differences estimates show, among other things, that the reform led to an increase of labor participation of the individuals who fell sick only if these individuals had a permanent job, whereas spouses responded to the DI reform in other cases, where the individuals reporting sick had a temporary job or were unemployed. More generally, the spouses respond when the sick individual’s labor market position is weak and the individual him- or herself has trouble finding or retaining employment. The effects are persistent during the 10 years after the reform. The effect on the spouse can be seen as an “added worker effect,” where additional earnings of the spouse compensate for the sick individual’s income loss so that both partners share the burden of a more stringent DI scheme. Comparing individuals reporting sick with and without partner provides further support for the notion that the responses of couples to the reform are joint decisions of the two partners.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

A large and growing strand of the literature analyzes income complementarities in the household as an insurance mechanism. The “added worker effect” hypothesis suggests that married women respond to a negative shock on their husbands’ earnings due to unemployment by increasing their hours of paid work (Lundberg, 1985). Most studies find no or a small added worker effect (Bredtmann et al., 2018; Cammeraat et al., 2023; García-Gómez et al., 2012; Halla et al., 2020; Jolly & Theodoropoulos, 2023; Maloney, 1987, 1991; Spletzer, 1997). One explanation is that the affected partner is insured through social insurance so that the spouse does not need to respond (Cullen & Gruber, 2000; Bentolila & Ichino, 2008). Couples may also self-insure through savings and run down their wealth in response to a negative income shock (Blundell et al., 2016). Similarly, the wife’s response may be small if the husband’s unemployment only leads to a transitory reduction in earnings (Cullen & Gruber, 2000; Bredtmann et al., 2018) or if the husband’s unemployment is anticipated by the household and the expected income loss already led to adjustments in household consumption and labor supply. In addition, the wife’s response will depend on the magnitude of the expected loss in lifetime income (Cullen & Gruber, 2000; Stephens, 2002; Bredtmann et al., 2018). An alternative explanation is that the wife’s employment prospects may be affected by the factors causing the husband’s unemployment (Cullen & Gruber, 2000).

Some recent studies, however, do find a notable added worker effect. Ayhan (2018) finds that the probability of a woman participating in the labor force increases by up to 28% in response to her husband’s unemployment, although only for two quarters. Schøne and Strøm (2021) find that the rise in wives’ labor supply compensates around one third of the loss in husbands’ earnings. Moreover, Blundell et al. (2016) show that of the total amount of consumption insured against permanent shocks to the husband’s wage, about 63% comes from family labor supply.

In this paper we investigate the existence of an added worker effect in the context of a DI reform that limited DI eligibility. The DI context is interesting for several reasons. First, the number of DI recipients is large and growing in many countries, creating an important challenge for social security funding (OECD, 2018). Moreover, workers who lose income due to the reform have health problems limiting their possibilities to work and recover the income loss themselves—and the income loss is more likely to be permanent than in case of unemployment, which is often temporary. Finally, the reform weakens protection from social insurance, raising the need for self-insurance of the household, for example through a spousal response. Indeed, Bredtmann et al. (2018) show that added worker effects are larger in countries with less protection from social insurance schemes.

In the Netherlands, the share of people receiving DI benefits in the insured population reached about 11%, with almost one million DI recipients in 2002 (Koning & Lindeboom, 2015). To reduce this number and promote work resumption, successive governments implemented several DI reforms. In 2006, the Work and Income According to Labor Capacity Act (WIA) came into effect, replacing the (transitional) Disability Insurance Act (WAO) as the final element of these reforms. WIA introduced major changes in both the DI scheme and the sickness insurance (SI) scheme preceding it, making it much more difficult to become eligible for and to stay on DI benefits. WIA introduced stricter entry criteria for DI and stronger incentives for work resumption, both for employees and employers.

Kantarcı et al. (2023) analyzed the effects of the WIA reform on labor participation and benefit receipt among long-term sick individuals (with and without partner) who report sick, i.e., are unable to perform their work because of occupational or nonoccupational illness or injury.Footnote 1 They found that the reform from transitional WAO to WIA substantially reduced the probability of DI receipt during the first 10 years after the reform. They also found a rise in labor participation and in unemployment benefits receipt that adds up to almost half of the fall in DI receipt. The labor participation response was particularly strong for those who had a permanent contract when they fell sick and had more possibilities to go back to work than those who had a temporary contract or were unemployed. Since couples can pool income risk, spousal labor supply can be an insurance mechanism to compensate for the loss of DI benefits, particularly if the individual who fell sick does not manage to go back to work. Such a spousal response might be dampened if the spouse needs to provide care to the sick individual, not allowing her or him to do (more) paid work.

The current paper therefore focuses on whether spouses also responded to the reform—and how such a response varied depending on the labor market position of the individual who fell sick. Taking a difference-in-differences approach, we analyze the reform effects on both the individuals who fell sick and their spouses, focusing on heterogeneity of the effects: for individuals with a weaker initial labor market position, i.e., fewer opportunities to go back to work after recovery, there is a larger need for the spouse to compensate for the more stringent rules of the new DI system. Sick individuals who had a permanent work contract at the time of reporting sick increased labor participation, and indeed we find that their spouses did not respond. On the other hand, the fact that sick individuals who had a temporary work contract did not manage to increase labor participation, induced a substantial rise in their spouses labor participation. Similarly, if sick individuals had a weaker labor market position in the sense that they worked in a sector with a low vacancy rate or earned a low wage, the sick individuals themselves hardly responded but their spouses’ labor participation rose substantially. These effects are persistent over a period of 10 years after reporting sick. Findings for other outcomes (earnings, UI benefits) confirm that the spouse’s response is larger in case of a weaker labor market position of the sick individual.

Finally, we compare the reform effects of sick individuals who have a spouse with the effects on those who do not have a spouse. If there is no spouse who could compensate the loss of household income, the reform raises labor participation of sick individuals with a weak labor market position much more than if there is a spouse. This is in line with our main finding that in couples, the negative income effect of the DI reform is shared by the two partners—single sick individuals cannot rely on their partner and make a greater effort themselves to resume work.

Our findings add to the limited evidence for the added worker effect, but also contribute to the literature on the impact of DI reforms. This literature analyses the effects of changes in screening process and eligibility criteria (Karlström et al., 2008; De Jong et al., 2011; Staubli, 2011; Moore, 2015; Autor et al., 2016; Hullegie & Koning, 2018; Godard et al., 2022), benefit generosity (Gruber, 2000; Campolieti, 2004; Marie & Vall Castello, 2012; Mullen & Staubli, 2016; Deuchert & Eugster, 2019), and return-to-work incentives (Kostøl & Mogstad, 2014; Koning & van Sonsbeek, 2017; Ruh & Staubli, 2019; Zaresani, 2018, 2020). It also studies welfare effects (Low & Pistaferri, 2015; Deshpande, 2016; Fevang et al., 2017; Haller et al., 2023). None of these studies consider spillover effects on the spouse. Our findings suggest that for a complete evaluation of the DI reform, it is important to consider such spillover effects on both labor participation and the adequacy of household income.

At the intersection of the literature on the added worker effect and the impact of DI reforms are a few studies that analyze spousal labor supply responses when sick individuals receive DI benefits or eligibility rules for DI benefits change. Results of Duggan et al. (2010) suggest that reform in the US disability program for veterans increasing enrollment, somewhat reduced their wives’ labor supply. Borghans et al. (2014) studied the impact of reassessing existing Dutch DI recipients and new applicants younger than 45 years based on new DI eligibility criteria. They found that affected individuals increased their earnings and social support income, but they found no significant effect on spousal earnings. Autor et al. (2019) analyzed the consequences of DI receipt for labor supply and consumption decisions in Norway. They showed that DI denial has little impact on income and consumption of married couples since spousal earnings and benefit substitution counteract the effect of denial of DI benefits. García-Mandicó et al. (2021) analyzed the impact of reassessment of earnings capacity under more stringent rules introduced in 2004. They found that earnings responses of the DI recipient and the spouse together almost fully compensate for the cut in DI benefits.

Our study differs from these studies in several respects. First, the DI reform in 2006 differs from the reforms studied earlier, restricting access to DI for a large group of workers, and therefore possibly leading to a stronger need for a spousal response. Moreover, due to the administrative nature of our data, we have enough statistical power to analyze heterogeneity in the response. This allows us to show that job security, employment opportunities, and earnings level of the sick spouse are important for the reform effects on both spouses. We also show that the added worker effect is evident for both wives and husbands whereas earlier studies focus on wives’ responses to husbands’ income shocks. Moreover, unlike earlier studies, we also compare with singles, which helps to validate our finding that partners share the burden of the more stringent disability scheme after the reform.

This paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 explains the 2006 reform. Section 3 describes the data and the study sample. Section 4 gives descriptive evidence on the impact of the reform on spousal labor supply. Section 5 presents the empirical approach used to identify the effect of the reform. Section 6 discusses the results for couples and Section 7 compares with the reform effects on singles. Section 8 conducts some checks on the identifying assumptions. Section 9 concludes.

2 Disability insurance in the Netherlands and the 2006 reform

The current Dutch system of sickness and disability insurance (named WIA) protects against earnings loss due to incapacity for work and consists of a sickness scheme (SI) for the short term and a succeeding disability scheme for the long term. An individual working for an employer or receiving unemployment benefits (UI) who cannot work due to a health issue, reports sick and enters SI. While on SI, the development of the health condition and whether reintegration obligations are met are monitored by a certified company doctor from a private occupational health and safety firm. While the employer’s responsibility lasts for the entire 2-year period of sickness in case of a permanent contract, it lasts only until the contract ends in case of a temporary contract. Moreover, for workers employed through temporary work agencies, the contract ends as soon as the worker reports sick.

For workers with a permanent contract who report sick, the employer is obliged to pay at least 70% of the pre-sickness wage for a period of at most 2 years.Footnote 2 Workers with a temporary contract, those employed through a temporary work agency, and those who are entitled to UI have no employer to continue the wage payment and they are eligible to a sickness benefit of 70% of the pre-sickness wage from the Employment Insurance Agency. In fact, the Employment Insurance Agency takes over the role of the employer, both in paying benefits and facilitating reintegration.

Only after 2 years, a worker on SI can apply for the public DI benefit. Uniquely in the world, the Dutch DI scheme covers all causes of sickness, both occupational and nonoccupational. During assessment for DI, a formal diagnosis is made and work limitations are determined. The loss of earnings is determined by comparing the pre-sickness wage to the potential wage accounting for the health condition of the sick worker defined as the median of the highest wages the sick worker could still earn in three jobs judged suitable. These jobs are selected from a representative sample of jobs in the Dutch labor market matching the job capabilities and limitations of the sick worker. The loss of earnings as a percentage of the pre-sickness wage is called the disability grade. A minimum disability grade of 35% is required to qualify for DI benefits; a disability grade of 80% or more defines full disability and implies the individual qualifies for full DI benefits. The public disability scheme is funded by employer’s contributions, mostly flat rate, but partially also differentiated by DI risk (“experience rating”).

Preceding the current scheme, the Disability Insurance Act (WAO) was introduced in 1967 to provide compulsory public insurance against loss of earnings due to long-term work incapacity, independent of the cause of the disability. It implied a period of at most 1 year on SI and a minimum disability grade of 15% for DI benefit eligibility. During the late 1970s and 1980s the number of DI beneficiaries rose rapidly to levels far beyond earlier expectations. Entry to the scheme was relatively easy because few reintegration incentives existed during sickness and DI applications were often accepted in case of doubt. Moreover, exit from the scheme was neither incentivized nor closely monitored. As a result, there was a substantial share of hidden unemployment in the DI scheme (Koning & van Vuuren, 2007).

Although major amendments were implemented in 1993, the WAO preserved its main features until 2006. The annual inflow rate into WAO rose to 1.5% of the insured working population in 2001, leading to further reforms. In April 2002 the “Gatekeeper Protocol” was introduced, in which clear and concrete mutual obligations of employers and sick employees for reintegration during the sickness period were specified. A “transitional WAO” s scheme was introduced on October 1, 2004, for people who reported sick between October 1, 2003, and January 1, 2004, making entry criteria stricter. In particular, it adapted a broader definition of the work that the applicant could still do. For example, a sick part-time worker was now supposed to be able to accept a full-time job given the limitations of sickness, and a sick worker who did not speak Dutch was supposed to learn the language to qualify for jobs requiring understanding the Dutch language. As a result, the estimated wage loss due to disability was reduced, making it harder to reach the minimum disability grade to qualify for DI or to reach a higher disability grade (with a higher benefit).

The current Work and Income According to Labor Capacity Act (WIA) was introduced in 2006 for people who reported sick from January 1, 2004, onwards. It introduced major changes in both sickness and disability schemes, stimulating work resumption. It reduced the annual inflow rate into DI to 0.5% of the insured working population during the first 6 years after its introduction (Koning & Lindeboom, 2015).

WIA extended the duration of the sickness scheme from 1 to 2 years, implying an extension of two main incentives: first, the employer is obliged to compensate the employee for 70% of the wage loss during the additional year in the sickness scheme, creating a strong incentive for the employer to facilitate work resumption. Second, the Gatekeeper protocol was extended to a second year of sickness, strengthening the employers’ sickness monitoring obligations (Hullegie & Koning, 2018).

WIA kept the stricter DI eligibility criteria of the transitional WAO scheme with the broader definition of what work can still be done. It introduced three other changes. First, the minimum disability grade for entering the scheme rose from 15 to 35%—workers with limited disability are expected to resume working (with adaptations of their work if necessary) or apply for UI. Second, it introduced a work resumption program providing strong financial incentives for partially disabled people to utilize their remaining work capacity. Third, experience rating for employers was extended from 5 to 10 years, implying that employers incurring disability costs are penalized with higher DI premiums for up to 5 additional years. At the same time experience rating was restricted to temporarily or partially disabled workers but abolished for permanently and fully disabled workers. Targeting the former group made experience rating more effective since the partially or temporary disabled have better prospects of reintegration. Experience rating was limited to permanent work contracts until 2013 and extended to temporary contracts afterwards. Figure 4 in Appendix A presents a timeline of changes in the DI scheme starting from the introduction of the WAO in 1967 until the extension of experience rating to temporary contracts in 2013.

For the income of the sick individuals during sickness and disability periods, potential implications of the WIA reform are as follows. In the first year of sickness, wages are not affected by the reform. However, employers may already do more for reintegration in the first year of sickness if they anticipate the cost of the additional year of wage payments. These stronger employer incentives may induce sick individuals to return to work, especially in combination with the requirements of the Gatekeeper protocol. On the other hand, reintegration incentives for employees might have become weaker in the first year since employees are no longer subject to a DI assessment after 1 year of sickness.

In the second year of sickness, WIA requires that the employer replaces (at least) 70% of the former wage. In WAO, DI and UI benefits together replaced 70% of the former wage. From the third year onwards, a potential fall in income is due to lower or a complete loss of DI benefits. As described above, this owes to the stricter eligibility criteria for DI, financial incentives for work resumption, and extended and more targeted reintegration incentives of experience rating. Note that these implications of the reform assume that the sick individual has a stable work contract with an employer. Employees with weak employer relationships or those who are unemployed will lack the reform incentives and may struggle to resume work and cope with the negative income shock of the reform. They may seek alternative welfare benefits, or rely on the income of their spouse.

3 Data

We use unique administrative data from the Employee Insurance Agency on all individuals who fell sick in the fourth quarter of 2003 or the first quarter of 2004, and therefore could become eligible to either the transitional WAO or the WIA scheme. We observe the beginning and ending dates of their sickness, their gender, date of birth, and sector of economic activity. They either earned a wage or receive UI at the time they report sick—other groups cannot enter the sickness scheme. For wage earners, we observe whether they had a permanent contract, a temporary contract, or a contract through a temporary work agency at the time they reported sick. We link these individuals to administrative data on themselves and their partners (married or cohabiting) from Statistics Netherlands (CBS), with monthly information on wages and benefits (including DI and UI) from January 1999 to February 2014.

The initial data set has 171,281 individuals reporting sick. To select the estimation sample, we drop individuals who participate in the special disability schemes for the self-employed or for young people, since the rules and incentives for them are quite different. We also drop individuals who already received DI when they reported sick. We drop individuals in same-sex partnerships and only keep couples if their cohabitation started before reporting sick. We drop individuals whose spouse also reported sick between October 2003 and March 2004. Finally, we only keep those who spent more than 90 days in sickness leave, since employers only have to report sickness cases if they last longer than 90 days.Footnote 3 We divide the sample into a “control group” of individuals (and their spouses) who fell sick in the fourth quarter of 2003 and were insured under the transitional WAO scheme and a “treatment group” of individuals (and their spouses) who reported sick in the first quarter of 2004 and were insured under the WIA scheme. We will not consider individuals who reported sick before October 1, 2003, and fall under the old WAO scheme and refer to the transitional WAO group as WAO group from now on.

Based on the available data on wages and social security benefits, we define the following outcome variables: dummies that indicate labor participation and UI receipt, and the monthly amounts of wages and UI benefits. We transform earnings and benefit amounts as the natural logarithm of the amount plus 1, accounting for the skewed distribution and the zero values. During participation in the sickness scheme, the observed wage combines two types of payments: earnings (for the part of work capacity that is still used) and compensation for lost earnings due to sickness benefits paid by the employer. We do not observe the separate amounts. Since we measure labor participation as positive earnings, this implies that we cannot determine whether or not sick people are working when in the sickness scheme. We therefore discard the first 2 years after individuals reported sick in most of our analysis. After the first 2 years, SI expires for everyone and measuring labor force participation is no longer problematic.

4 Time trends and other descriptive statistics

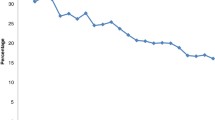

Figure 1 shows the labor participation rates and fractions of DI and UI recipients in control and treatment groups over the observation period.Footnote 4 For the individuals in our data who all reported sick, DI benefit receipt increases sharply when they become eligible for DI benefits and continues to increase during the remaining years of the observation period. The WIA group is 3 pp less likely to receive DI benefits than the control group (13.5% versus 10.5%) and the difference between the two groups remains stable till the end of the observation period. This shows that the reform effectively limited access to DI benefits. For the spouses of sick people, DI receipt is stable and not affected by the reform (as expected).

For individuals who reported sick, the probability of working shows a strong time trend that is common to both groups. It increases until the date individuals report sick, reflecting that individuals can enter the sickness scheme only if they are working or receive UI. Before this, they can have another labor force status. The probability of working falls sharply during the first few years of sickness and continues to fall throughout the remaining years. The difference between WAO and WIA groups is small and insignificant before individuals fall sick, but notable and significant after that, suggesting that the reform increased labor participation of those who fell sick. For spouses, the probability of working shows a less pronounced decreasing pattern. The difference between groups is smaller before than after treatment, which would be in line with a positive spillover effect, but these differences are not significant.

For sick individuals in both groups, the use of UI falls sharply right after reporting sick, since those who are unemployed replace UI with sickness benefits. UI use rebounds and increases during the remaining months of the sickness scheme, since many individuals recover and replace their sickness benefit with UI. UI use peaks when individuals can apply for DI, since rejected DI applicants turn to UI when the sickness period ends. UI use falls during the disability period because UI is temporary with a maximum of 38 months. The difference between the control and treatment groups is sizable and statistically significant during the disability period, suggesting that the DI reform increased UI use among those who reported sick. UI use among the spouses is fairly constant over time. The difference between control and treatment groups is insignificant, both pre- and post-treatment.

Table 1a presents sample means of some background characteristics when reporting sick for both groups, as well as outcomes before and after reporting sick. It also presents tests for equality of the means in control and treatment groups (“balancing tests”). Panel (a) shows that, in both groups, the average age is about 43 and there are more men than women. The majority held a permanent work contract when they fell sick; the others had a temporary contract or a contract through a temporary work agency, or were unemployed. Column 3 shows that there are small but significant differences between the treatment and control group. These possibly reflect labor market trends. Our identification strategy (difference-in-differences) accounts for such differences.

Columns 3 and 6 in panel (b) present mean differences in outcomes during the pre- and post-treatment periods for treatment and control group. The fraction of sick individuals receiving disability benefits falls due to the reform, as expected. In line with Fig. 1, the difference is larger post- than pre-treatment for all outcomes, again suggesting that the reform has increased labor participation, average earnings, UI receipt, and the average amount of UI benefits.

Table 1b reproduces Table 1a for the spouses. Spouses in the treatment group are slightly older than in the control group. Couples in the treatment group have cohabited somewhat longer pre-treatment but not post-treatment. Columns 3 and 6 in panel (b) show that the difference in labor participation between groups is larger post-treatment than pre-treatment, which, again, might suggest that the reform increased labor participation for the spouses. The mean differences in other outcomes are small and insignificant, both pre- and post-treatment.

5 Identification strategy

We use a difference-in-differences approach to identify the causal effect of the WIA reform on each outcome variable yit, either concerning the sick individual or the spouse. The first difference is across groups. Those who reported sick in the first quarter of 2004 (treatment or WIA group) face different eligibility criteria and incentives to work or claim benefits than individuals who reported sick in the fourth quarter of 2003 (control or WAO group). The second difference refers to event time: before and after reporting sick.

We start the DiD comparison using the following baseline regression model:

Here i indexes the sick individual or the spouse. t indexes the month of event time: Values –57 to –1 indicate the months before reporting sick, 0 is the month when first reporting sick, and 1–119 are the months after reporting sick. (For some outcomes yit, we do not use observations during the sickness period due to measurement issues; see Section 3). λs(i, t) is a monthly calendar time effect—s(i, t) indexes the calendar month (from January 1999 until February 2014; January 1999 is chosen as the base month) for individual i at a given month of event time t. αi is an individual-specific, time-invariant fixed effect that is potentially correlated with the control variables. εit represents an idiosyncratic (unobserved) shock, assumed to be uncorrelated with all the explanatory variables.

Treatedi is a dummy variable for the treatment (WIA) group.Footnote 5Postt is an event time dummy with value 1 from the start of the sickness period. The individual effects capture differences between the two groups other than the reform effect. Under the identifying assumption that treatment and control group would have followed the same trend if there would not have been a reform, the coefficient γ on the interaction term Treatedi × Postt captures the effect of the reform, the parameter of interest.Footnote 6

To disentangle the effect of the WIA reform in the short and long run, and test for the common trend assumption, we consider the following extended model:

Instead of Postt which refers to the entire period after falling sick, this model has separate dummies for each year, after and before falling sick. dlt indicates the lth year from the time the individual reports sick. Year − 1 is chosen as the base year. The coefficients on the interaction terms of treatment and these year dummies are the estimated treatment effects.Footnote 7 For the years before reporting sick, they provide a test of the common trend assumption. For the period after reporting sick they reflect the dynamic effects of the reform. In this setup, treatment and control groups are compared over event time t, i.e., the months before and after the individual reported sick. The calendar time dummies λs(i, t) on the other hand capture the (common) calendar time trend.

In Section 6.3, we allow for heterogeneous reform effects depending on the labor market status at the time the individuals reported sick. In particular, we hypothesize that the effects depend on how easy it is for the sick individuals to go back to work (either to their old job or to a new one). In Section 7, we also apply the same model to individuals without a spouse who reported sick. This is to investigate whether the sick individuals behave differently if there is a spouse who can potentially respond to the reform by increasing labor supply and household income.

To control for observed differences between treatment and control individuals before reporting sick, we apply entropy balancing following Hainmueller (2012). In particular, individuals are weighted to adjust inequalities in representation with respect to the first moment of the covariate distributions. As covariates, we consider their gender and birth year, as well as all outcomes of the sick individuals and their spouses before the first group reported sick. Regressions of Eqs. (1) and (2) are estimated based on the constructed weights.Footnote 8 The weights are regenerated in each subsample when analyzing heterogenous treatment effects. To check whether, after entropy balancing, the common trend assumption is satisfied pre-treatment and to analyze several other threats to our identification strategy, we perform additional analyses and robustness checks in Section 8.

6 The effect of the reform on labor participation of sick individuals and their spouses

We first present the effects for the whole post-treatment period (Eq. (1)), then analyze the short- and long-run effects of the reform (Eq. (2)), and finally check for heterogeneous effects. In the main text, we focus on the reform from transitional WAO (often referred to as WAO for convenience) and WIA. To further substantiate our main conclusion about the added worker effects, we repeated some of the analysis for the reform from (original) WAO to transitional WAO 3 months earlier. These results are presented in Appendix E.

6.1 Baseline effects

Table 2 presents the baseline DiD estimates of the reform effects on labor participation and benefit receipt. For the sick individuals, the reform decreased the probability of DI receipt by 3.1 percentage points (pp) on average during the post-treatment period (excluding the first 2 years). It increased the probability of working by 1 pp and UI receipt by 0.8 pp.Footnote 9 The reform induced the spouses of the sick individuals to raise their labor participation by 0.5 pp, one sixth of the drop in DI receipt of the individuals who reported sick, but this effect is significant at the 10% level only.

The center panel of Table 2 shows the DiD estimates of the reform effects on monthly wages and benefits (in log of the amount plus 1). The reform reduced monthly DI benefits of individuals reporting sick by 20.3% and increased monthly earnings by 7.6% and monthly unemployment benefits by 5.6%. Moreover, it increased earnings of spouses by 3.6%, but this increase is not statistically significant.

The lower panel of Table 2 presents the DiD estimates of the reform effects for monthly total income (in log of the amount plus 1), pooling monthly wages and social security benefits (DI, UI and social assistance). It presents the total income of sick individuals and their spouses at the individual level, but also total income of the couple. On average, the reform did not significantly affect total income of sick individuals, their spouses, or their household. The first suggests that in most cases, sick individuals are able to compensate lost disability benefits by increasing earnings and income from UI. This may explain why the spouses’ income increase is not that large (or significant) either—there is not much need for a spousal response. In the heterogeneity analysis in Section 6.3, however, we will find that this aggregate result is mainly due to groups of individuals reporting sick who relatively easily can go back to work and increase their earnings. The aggregate findings fail to show that for individuals reporting sick and who are less likely to compensate lost disability benefits by responding themselves, spousal earnings do respond.

6.2 Dynamic effects

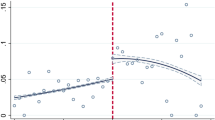

Figure 2 presents the estimates of the reform effects separately for 10 years of the post-treatment period. For individuals reporting sick, the reform reduced DI receipt by about 3 pp from the third year after reporting sick, when both the treatment and the control group can apply for DI. (Note that the large effect of the reform on labor participation during the first year of the sickness scheme is hard to interpret, due to the measurement issue explained in Section 3.) The effect on labor participation then falls to about 1 pp and remains fairly stable. For UI receipt, the large negative effect in the second year of the sickness scheme is due to the fact that individuals insured under WIA are still entitled to sickness wage payment if there is an employer, or the sickness benefit if there is no employer. From the third post-treatment year onwards, however, the reform has a positive effect on UI receipt. It falls over time and becomes insignificant from year 8 after reporting sick.Footnote 10 In each year after reporting sick, the effect of the reform on spousal labor participation is about 0.5 pp, but this is never significant. Moreover, in line with the exploratory analysis in Section 4, the reform has no significant effect on spouses’ UI receipt.

6.3 Heterogeneous effects

Analyzing wives’ labor supply responses to an exogenous shock to husband’s job earnings in Austria, Halla et al. (2020) find that the added worker effect for wives is almost negligible if computed for their full sample. To understand the reasons for this and to identify impediments to the intrahousehold insurance mechanism, they investigate heterogeneity in responses for different types of households and find significant added worker effects for several subgroups. Similarly, as shown in Table 2, we also found a small added worker effect for the sample as a whole. This finding, however, may mask interesting heterogenous effects.

Existing studies on the added worker effect discuss a variety of factors that could induce wives to respond to a negative shock on their husbands’ earnings. Some consider the nature of the income shock and argue that spouses would respond if the income shock is permanent, unanticipated, or if its magnitude is large (Cullen & Gruber, 2000; Stephens, 2002; Blundell et al., 2016; Bredtmann et al., 2018; Fadlon & Nielsen, 2021). Others consider that lack of self-insurance through savings or formal insurance through social support programs, high earnings potential of the wife, and existence of job opportunities for wives may encourage wives to respond (Cullen & Gruber, 2000; Bentolila & Ichino, 2008; Blundell et al., 2016; Halla et al., 2020).

Our heterogeneity analysis starts from the notion that the need for a spousal response in order to maintain family income depends on the extent to which the individual reporting sick is unable to respond him- or herself. We hypothesize that when the labor market position of a sick worker facing the reform is weak, the sick individual’s response will be weaker and the spousal response will be stronger. The heterogeneity analyses we perform essentially distinguish in three different ways among groups of individuals reporting sick that differ in their chances to go back to work. We explore three indicators of a weak labor market position: employment status just before reporting sick (permanent job, temporary job, or unemployed), earnings level before reporting sick, and the sectoral vacancy rate in the year of reporting sick.Footnote 11Figures 5–7 in Appendix B present the dynamic effects by employment status, vacancy rate, and earnings quartile for sick people with a spouse and their spouses, and also sick people without a spouse (discussed in Section 7). The pre-reform (left hand) parts of these figures show negligible and insignificant pre-reform effects, supporting the common trend assumption for each subgroup.

6.3.1 Employment status just before reporting sick

If sick individuals have temporary work contracts, they may not be able to go back to their job after recovery or find another job. Similarly, workers who reported sick while unemployed may have trouble finding a job when their sickness benefit expires. Furthermore, stimulating employers to increase labor market participation has been a key element of Dutch labor market reforms throughout the years. The WIA reform in particular introduced strong reintegration incentives for employers (see Section 2), but these incentives do not apply uniformly to all workers: Employer incentives for temporary workers only last for the duration of the employment contract. Moreover, temporary work agencies do not face incentives for their sick employees during sickness, since their sickness benefits are paid by the Employee Insurance Agency. Unemployed individuals obviously do not benefit from positive effects of employer incentives either. On the other hand, employers of employees with a permanent contract are fully incentivized due to continued wage payments and experience rating, which applied only to permanent work contracts until 2013. Prinz and Ravesteijn (2020) found that the extension of experience rating to temporary workers reduced DI receipt by 12.7 pp and increased labor participation by 2.5 pp among workers with temporary contracts relative to those with permanent contracts. In summary, there are several reasons why those who had a temporary contract or were unemployed when falling sick have more problems to go back to paid work after recovery and more often have to cope with a negative income shock due the reform. They may then also more often have to rely on their spouse’s income, and their spouse may respond more strongly if DI benefits are lost due to the reform.

We separately estimate the reform effects for individuals who were wage earners with a permanent contract, wage earners with a temporary contract, or unemployed just before they started receiving sickness benefits. Since changing jobs takes time and involves adjustment costs (Zaresani, 2020), this makes selection into employment situation before falling sick due to the onset of the health problem very unlikely. On the other hand, as suggested by Koning and Lindeboom (2015), employers might respond to the reform by hiring fewer high-risk workers on a permanent basis. While this might play a role in the longer run, the data suggest that this issue is not relevant for the cohorts under study that fall sick just before and just after the reform. In fact, Table 1a shows that the post-reform WIA group has slightly more people with a permanent contract and fewer with a temporary contract than the pre-reform WAO group, the opposite of what selection would predict. Our results therefore are unlikely to be biased by different selection into temporary and permanent jobs for the pre- and post-reform groups.

The upper panel of Table 3 presents the results, which are largely in line with the hypotheses formulated above. Due to the reform, DI receipt fell substantially for all groups, and the largest fall is for the unemployed, who have no employer that can help them resume work. This increases their chances of remaining in the sickness scheme and facing the stricter requirements of WIA to enter DI.

The reform only increased labor participation among those who reported sick when they had a permanent work contract, even though the fall in DI receipt is larger for the other two groups. It suggests that the reform’s work resumption incentives induced employers to reintegrate their permanent employees, but were not effective for temporary contracts or unemployed workers. For the unemployed, the longer sickness period may also lead to more human capital loss or a stronger scarring effect, reducing the prospects of finding a job (Arulampalam, 2001; Arulampalam et al., 2001). Moreover, their incentives to resume work quickly may be reduced by the additional year they can spend in the sickness scheme.

The reform increased UI receipt for all sick individuals, irrespective of their work status. The increase is largest for the unemployed, where UI is usually the primary source of income. The effect for those on a temporary contract is larger than for those on a permanent contract—the former have lower and less stable earnings, and seek additional income from UI if the reform blocks access to DI benefits.

Since sick individuals with a permanent work contract often resume work and increase earnings themselves, their spouses less often need to compensate, and indeed, the labor participation response of the spouses in this group is small and insignificant. On the other hand, the spouses of sick individuals on a temporary contract increased labor participation and earnings significantly and Fig. 5 in Appendix B shows that this effect is persistent.Footnote 12 Since sick individuals with a temporary contract struggle to resume working, this confirms that their spouses increase labor participation and earnings to compensate for the lost disability benefits and lack of labor income. This added worker effect on labor participation is particularly large—81% of the drop in DI receipt. The spouses of sick individuals who were unemployed also increase their labor participation by a notable amount of 1 pp, but this estimate is less precise and not significant.

The signs and significance levels of the estimated effects of the reform on earnings and benefit amounts in the upper panel of Table 4 are in line with the estimated effects on labor participation and benefit receipt. The upper right panel of Table 4 presents the effects of the reform on total income (in log of the amount plus 1) of sick individuals and their spouses at the individual and the household level. Individual income of sick individuals who had a temporary contract or were unemployed fell significantly due to the reform. However, due to the positive responses of their spouses, household income does not change significantly, confirming that spouses’ responses help to smooth household income. This result is in line with the findings of Blundell et al. (2016) based on a structural family labor supply model where households self-insure through spousal labor supply in case of a negative income shock. For sick individuals with a permanent contract, total income did not change significantly at either the individual or the household level.

6.3.2 Pre-sickness earnings

If sick individuals earn low wages (regardless of their sickness), spouses may respond more strongly for different reasons. Low-wage earners tend to have smaller savings or wealth to draw on during sickness to smooth their consumption path. They also tend to work in jobs where prospects of recovery from ill health are limited. If as a result the income shock becomes permanent, spouses may exhibit stronger responses. Furthermore, the likelihood of receiving DI benefits depends on the wage earned before reporting sick (Section 2). For people with low earnings, the income decline due to disability is often limited. As a result, low-wage earners are much more likely to be denied DI benefits than higher wage earners (OCTAS, 2023). The workforce hit by the DI reform therefore includes many low-wage earners who are more likely to rely on a spousal response to maintain household income. The pre-sickness earnings measure we use is the average of the individual’s earnings during the 5 years before they reported sick (where data is available). The center panel of Table 3 presents the estimation results by pre-sickness earnings quartile. Sick individuals in lower earnings quartiles increased their UI receipt somewhat more, in line with the argument that they struggle more to find suitable jobs where they can utilize their remaining work capacity and more often have to rely on income from UI. For the lowest two quartiles, we find that spouses notably increase their labor participation, a response which is more than half (52%) of the drop in DI receipt of the sick partner. For the higher quartiles, however, no spousal response is observed. These results are in line with the results based on employment status in the preceding subsection—both suggest that spousal responses are stronger for sick individuals in a weaker labor market position. Figure 6 in Appendix B suggests that the pattern is persistent over time, but the precision of the estimates is limited.

6.3.3 Vacancies in the sector

For sick individuals who have limited employment opportunities and hence a higher risk of unemployment, responding to the work incentives of the DI reform can be more difficult and spousal labor supply responses can be stronger. We consider the sectoral vacancy rate (the number of open vacancies per one thousand jobs) as an indicator of employment opportunities.Footnote 13 We distinguish two groups: individuals who at the time of reporting sick worked in sectors with vacancy rates below (e.g., construction, manufacturing, transport, public sector) or above the average vacancy rate (e.g., agriculture, trade, financial services, catering).

The lower panels of Tables 3 and 4 present the results. If sick individuals work in a sector with a vacancy rate below the average, their spouses increase labor participation by 0.9 pp, a sizable extensive margin added worker effect of 23% of the drop in DI receipt by the sick partner who has limited employment opportunities him or herself. In contrast, if sick individuals work in a sector where the vacancy rate is above the average, the reform raises their own labor participation by 1 pp while their spouses do not respond significantly. Again, these results confirm that the added worker effect is a more powerful insurance mechanism when the labor market position of the sick individual affected by the reform is weak.

7 Comparing with the reform effects on sick individuals without a spouse

The results in the preceding section suggest that spouses increased their labor participation to compensate for lost disability benefits of their sick partners, particularly if the sick individuals cannot increase their own earnings. Here we compare the reform effects on labor participation of sick individuals with and without a spouse. Since only sick individuals with a spouse can compensate the loss of household income through spousal labor supply, they might less often make the effort to go back to work than singles do, particularly if their labor market position is weak. Figure 10 in Online Appendix A compares labor participation and benefit receipt of sick people with and without a spouse of control and treatment groups. It suggests that indeed, the positive reform effect on labor participation is substantially larger for the sick individuals without a spouse. Figures for wages and benefit amounts lead to the same conclusions (not shown).

Table 12 in Online Appendix A presents summary statistics for sick people without a spouse. As before, the (small) differences between the treatment and control groups will be taken into account by our empirical strategy. Comparing with Table 1a, singles tend to be younger and more often female than sick people with a partner. They are also less likely to have a permanent contract at the time of reporting sick, which suggests it might be important to allow for heterogeneity by labor market conditions.

Table 5 presents the DiD estimates of the reform effects for sick people without a spouse, and reproduces the baseline estimates for sick people with a spouse from Table 2.Footnote 14 The estimates confirm that the reform increases the probability of working post-treatment by 1.2 pp more among sick people without a spouse than for sick individuals in couples. Compared to the effects on DI receipt, the effects on labor participation are almost twice as large for singles than for partnered individuals: 61% vs. 32%. Together with the earlier finding that spouses increase their labor participation in response to the reform (Table 2), this suggests that in couples, the response to the disability reform is shared by both partners: Spousal labor supply is a substitute for sick individuals’ own labor supply. The reform effects for earnings and benefits are in line with this. For example, sick people without a spouse increase their earnings by 15.8% in response to the reform, whereas for sick people with a spouse the increase in earnings is only 7.6%.

As in Section 6, we consider the possibility that the reform effects depend on the time since the individual fell sick, see Fig. 8 in Appendix B. The time patterns of the effects on labor participation are similar for sick people with and without a spouse, but substantially larger for sick people without a spouse, also in the long run. The time patterns of the effects on DI and UI receipt are also similar to those with and without a spouse—persistent and significant throughout the entire post-treatment period. Similar time patterns are found for the effects on wage and benefit amounts (not shown).

In Section 6.3 we analyzed heterogeneity in labor supply responses to the DI reform to better understand how couples make joint labor supply decisions. We conducted a heterogeneity analysis for singles and compare with individuals in couples in Table 6.Footnote 15 Like before, we focus on heterogeneity in terms of labor market position when falling sick, characterized by type of contract (top panel), earnings level (middle panel), or vacancy rate in the sector (bottom panel). First, the effects of the reform on the chances to receive disability benefits after the sickness period are negative and similar for individuals in couples and singles in all cases. The point estimates tend to be somewhat larger for singles, but the differences with partnered individuals are not significant, even though individuals in couples and singles may also differ in other characteristics. The most interesting part in the table is the middle column. Individuals with a relatively strong labor market position (permanent contract, high earnings, or low vacancy rate sector) respond themselves, irrespective of whether there is a spouse or not. In particular, the responses for singles and non-singles with a permanent contract are remarkably similar, even though the two groups may differ in many other characteristics. This group has relatively good chances to go back to work and does not need to rely on a partner (if there is one). On the other hand, the sick individuals that more often struggle to go back to work (temporary workers, for example) respond much more if they are single than if they have a partner. It suggests that in these cases, it is easier for couples if the partner of the sick individual responds, whereas for singles this option does not exist, and the individual makes a larger effort to go back to work. The effects on UI receipt never differ significantly between sick individuals with and without a spouse.

Similar results are obtained for monthly earnings and benefits (Table 7). The main difference between sick individuals with and without a spouse is the response in earnings for those on a temporary contract or in the lower pre-sickness earnings groups: it is much larger for singles, who cannot compensate the loss in household income through spousal earnings. There is not much difference between the reform effects on labor participation in the sectors with lower and higher vacancy rates, suggesting the vacancy rate is not a strong indicator of the opportunities to go back to work.

Figures 5–7 in Appendix B present the dynamic effects by employment status, vacancy rate, and earnings quartile for all groups: sick people with a spouse, their spouses, and sick people without a spouse. They are in line with the main findings. In groups where spouses respond, sick individuals without spouse also respond, confirming that in couples both partners share the burden of a more stringent DI scheme. The estimated effects at individual event years are not always significant at the 5% level, however.

8 Checking the identifying assumptions

8.1 Is the pre-treatment time trend common to control and treatment groups?

Our main identifying assumption is that, conditional on observables, control and treatment groups share the same time trend in the potential outcome variables before and after individuals report sick and face the reform incentives or not. The assumption is testable during the pre-treatment period. Figure 1 already suggested that control and treatment groups, both for sick individuals and their spouses, share very similar time trends until individuals fall sick, supporting this identifying assumption. For a formal test, we use Eq. (2). Statistically insignificant estimates on the treatment and annual dummy interactions during the pre-treatment period provide evidence supporting the assumption. Year − 1 is chosen as the base for comparison. Figure 2 plots the estimates for sick individuals (left hand panel) and their spouses (right-hand panel). For both groups and all outcomes, the estimates are insignificant throughout the pre-treatment period. They are also jointly insignificant, with p values of at least 70%. The estimates are also (individually and jointly) insignificant for wages and benefit amounts, and in all subgroup analyses of heterogenous treatment effects—see Online Appendix B.

8.2 Placebo test: is a treatment effect absent in a non-reform year?

The effects we find could be not due to the reform but due to, for example, some seasonal effect that leads to different changes in labor market position for those who fell sick before and after January 1, 2004 (the control and treatment groups, respectively). To confirm that the effects we find are indeed due to the reform, we performed the same DiD estimation (Eq. (1)) comparing the groups who reported sick 1 year later (last quarter of 2004 and first quarter of 2005). Both groups fall under the new WIA regime so there should not be any reform effects. Table 8 in Appendix C shows that, indeed, for both the sick individuals and their spouses, estimated treatment effects are close to 0 for all outcomes, and insignificant at (at least) the 10% level.

8.3 Are the results robust to a regression discontinuity approach?

An alternative identification strategy is a regression discontinuity (RD) approach, using the date of falling sick as the running variable (since the reform applies to those who reported sick as of January 1, 2004). In Online Appendix C we present the results. Both identification strategies lead to the same qualitative conclusions for all outcomes and to similar relative sizes of the effects across sick individuals with and without a spouse and for spouses. On the other hand, the RD estimates are typically much larger than the DiD estimates. A possible explanation is that individuals who report sick just before and just after January 1 are different, due to the Christmas holidays. For example, workers in specific sectors or professions may continue working during the last weeks of the calendar year, whereas others do not. If the difference affects levels but not trends, this is accounted for in the DiD estimates but not in the RD estimates.

8.4 Do individuals self-select into the old or new disability scheme?

Reporting sick before or after January 1, 2004, determines eligibility for either WAO or WIA, implying that individuals with adverse health shocks in 2003 might select themselves into the WAO or WIA scheme from the time the reform is announced. In particular, the government presented a sketch of its reform plans on September 15, 2003, announcing that the sickness period would be extended from 1 to 2 years and that a stricter DI law would be introduced for individuals reporting sick as of January 1, 2004. The transitional WAO reform was announced on March 12, 2004, and details of the WIA reform were announced on August 18, 2004. Following the first announcement in September 2003, individuals could report sick during the last quarter of 2003 instead of after January 1, 2004, to enter the more lenient WAO scheme instead of WIA. In principle, they also might want to postpone their sickness claim until January 2004, to get an additional year of sickness benefits. This seems unlikely since the sickness benefit can fall from 100% of the former wage in the first year to 70% in the second year, generally making income while on sickness benefits lower than if on DI or UI (cf. Section 2). If individuals strategically choose the disability regime, our results could be biased.

We argue that such self-selection is unlikely. Figure 3 shows how many individuals reported sick in the last quarter of 2003 and first quarter of 2004. The distribution is fairly uniform and does not suggest any particular pattern. It certainly does not suggest that many individuals report sick in the last quarter of 2003 instead of early 2004. On the contrary, if anything, there are more sick reports in January 2004, after the stricter WIA scheme was introduced. The relatively low number of workers reporting sick in December 2003 is probably due to a seasonal employment pattern in absence from work, implying that few people report sick during the Christmas and New Year holidays. This is confirmed by the numbers reporting sick 1 year after the reform, also presented in Fig. 3. This distribution is very similar to that the year before when the reform was introduced.

Distribution of the number of individuals reporting sick, among those who reported sick in the last quarter of 2003 and first quarter of 2004 and participated, respectively, in the WAO and WIA, and those who reported sick in the last quarter of 2004 and first quarter of 2005 and participated in the WIA

In addition, self-selection would be plausible among people with mild impairments only, who would be able to manipulate the timing of their sick reporting. However, both pre- and post-reform, the same Gatekeeper protocol was in place, according to which after 6 weeks of sickness a first reintegration plan has to be submitted to the Employee Insurance Agency by the employer. Due to this formal screening, mild sickness cases tend to be denied sickness benefits already at this stage.

Finally, if some individuals manage to select themselves into one of the two DI schemes, they would probably do this around January 1, 2004, when the WIA reform came into effect. If we exclude individuals who reported sick within 2 weeks before or after this date, our DiD results in the heterogeneity analysis remain very similar—see Online Appendix D.

8.5 Do couples separate due to the reform?

We study the labor supply responses of couples to the DI reform who started cohabiting before reporting sick. Cohabitation can end during the post-treatment period due to the reform or other reasons. In this case the estimated treatment effect may not only reflect the labor supply responses to the DI reform. In the sample, we find no statistical difference between the fractions of couples whose cohabitation ends in the treatment and control groups during the post-treatment period, suggesting that the reform has no effect on cohabitation status—see Online Appendix E.

8.6 Can compositional differences drive heterogeneity in the reform effects?

In Section 6.3 we documented clear reform effects of spousal labor supply responses for individuals reporting sick with a weak labor market position. A threat to our identification strategy might be that the two groups, e.g. permanently and temporarily employed, could differ in other observable and unobservable characteristics, correlated with employment status. For example, individuals with a temporary contract tend to be younger than individuals with a permanent contract. For younger individuals, sickness may represent a larger or more unexpected shock, they might have limited eligibility for UI, and they might have accumulated less wealth to smooth the negative income shock, all of which may lead to a stronger spousal response among younger couples. To address this, we consider gender and age as main variables driving compositional differences across labor market groups. We weigh individuals across labor market groups to have similar distributions of gender and age of the spouse across these groups. We then estimate Eq. (1) within each labor market group using the re-weighted sample of that group. In other words, we control for compositional differences between control and treatment group, but also between the groups with different labor market status when reporting sick. In Appendix D we show that the estimated treatment effects in heterogenous labor market groups are robust to these compositional differences across these groups, suggesting that spousal responses indeed stem from weak labor market conditions.

9 Conclusion

We have analyzed the labor supply and earnings responses of individuals who reported sick and their spouses to a major reform of the Dutch disability insurance (DI) system that introduced stricter eligibility criteria for DI and stronger employer and employee incentives for work resumption. An advantage compared to earlier studies is that we use unique administrative data that include everyone who spent more than 3 months on sickness benefits, not only the individuals who entered disability after the sickness benefit period expired. We focus on the added worker effects on spouses: Since couples can pool income risk, spousal labor supply can be an important self-insurance mechanism to counterbalance the loss of income due to the reform. Based on a difference-in-differences identification strategy, we find clear evidence of an added worker effect for spouses of workers who report sick from a weak labor market position where work resumption is difficult. Compared to the reform effect on disability benefit receipt and work resumption of the sick individuals themselves, the effect on the spouse’s labor participation is substantial (about one sixth and one half, respectively). This finding is notable given that an earlier major DI reform (implemented in 1993) had no significant effect on spousal labor supply (Borghans et al., 2014). It implies that for a complete evaluation of the DI reform and its effects on labor participation as well as adequacy of household income, it is important to consider spillover effects on spouses.

The effect of the reform on spousal labor supply depends on the type of the employment contract of the sick individual when falling sick. People who had a permanent contract at the time they fell sick increased labor market participation by 1.6 pp due to the reform, while their spouses did not respond. On the other hand, people who had a temporary contract when they fell sick did not increase labor participation because of the reform, but their spouses increased labor participation by 2.5 pp. Furthermore, the spousal response is persistent during the 10 years following the start of sickness. Overall, the response at the couple level is sizable regardless in all cases, driven by either the response the sick partners, or the spouses. The effect of the reform also depends on the vacancy rate in the sector where the sick individual was working: if this vacancy rate was above the mean, they increased labor participation by 1 pp themselves while their spouses did not respond, but if the sectoral vacancy rate was below the mean, only the spouses increased labor participation, by a significant 0.9 pp. Finally, spouses increased labor participation more often if their sick partners were low wage earners. All these findings support the hypothesis that partners substitute for each other’s labor force participation and spouses respond more often if the labor market position of the sick individual is weaker. Comparing individuals reporting sick with and without partner provides additional evidence for this hypothesis.

Most of the earlier estimates of the added worker effect are small. Our findings add to the few recent studies that find economically meaningful added worker effects (Section 1). On average, the extensive margin added worker effect is 16%, as spouses’ labor participation increases by 0.5 pp in response to the 3.1 pp drop in DI receipt for sick partners due to the reform. The extensive margin added worker effect attains 81% for sick partners with temporary contracts and it attains 52% and 23% respectively for sick partners with low earnings and for sick partners working in a low vacancy sector. There are several reasons why the 2006 Dutch DI reform did lead to a substantial added worker effect. First, the reform often led to a permanent reduction of the income of the affected individual. In line with this, we find persistent responses of both the sick individuals and their spouses in the 10 years following sickness (Fig. 2). Second, the reform could not be anticipated so that couples could not adjust their consumption and labor supply before the reform took place. Third, as the DI reform limited DI entitlement, social protection has become weaker and the need for households’ self-insurance increased. These arguments apply particularly if the chances to resume work for the individual who fell sick are small, e.g., when the sick individual had a temporary work contract or was unemployed.

In this paper, we have focused on the WIA reform, replacing the final version of WAO (transitional WAO) by WIA. Using the same source of data and control and treatment groups that reported sick 3 months earlier, we checked our main findings by performing the same analysis for the reform that introduced the transitional WAO to replace the WAO system preceding this. In Appendix E, we reproduce Table 2 and Fig. 2 for the impact of this reform, comparing sick people who participated in the transitional WAO scheme to those who participated in the WAO scheme preceding this. We find a large participation response of the individuals reporting sick, but no added worker effect on the spouse. This is in line with our main findings since if the sick individuals can respond themselves, there is no need for a spousal response in order to maintain household income.

Data availability

Results are based on calculations by the authors using non-public microdata from Statistics Netherlands. Under certain conditions, these microdata are accessible for statistical and scientific research. For further information: microdata@cbs.nl.

Notes

This concerns all types of health problems, such as virus infections, mental health issues, headaches, stomachaches, back pain, etc.

Most employers pay the full amount during the first year of sickness.

Temporary work agencies have to report all sickness cases.

Similar figures for wages and benefit amounts (not shown) reveal very similar patterns.

Since this is time invariant, it is omitted in the fixed effects regression.

We cannot separately identify the effects of the different components of the reform, i.e. the extension of the sickness period, changes in financial incentives, and stricter eligibility criteria.

Here we also include observations for t = 0, …, 23.

Following Imbens (2004) and using propensity scores to construct weights leads to almost identical estimates.

This is qualitatively in line with what Kantarcı et al. (2023) found. The magnitude of the effect on DI receipt is different, mainly because we take everyone who has been sick for at least 90 days whereas Kantarcı et al. only consider those who have been sick for 180 days; see the sensitivity analysis in their Appendix B.

The literature on the added worker effect typically focuses on the wife’s response to shocks in the husband’s income. In contrast to García-Mandicó et al. (2021), who analyzed the impact of the change in reassessment rules in 2004, we found hardly any differences between the spousal effects for men and women.

The right-hand panel in this figure will be discussed in Section 7.

The sector where sick individuals are or were employed is available in the sickness data, and we determine the vacancy rate in each sector prior to and in the year of reporting sick using data from Statistics Netherlands.

Figure 8 in Appendix B presents the estimates of pre-treatment effects for sick individuals without a spouse for all outcomes, supporting the common trend assumption.

As for the partnered sick individuals, we find similar effects for male and female singles (results not presented).

References

Arulampalam, W. (2001). Is unemployment really scarring? Effects of unemployment experiences on wages. The Economic Journal, 111, F585–F606.

Arulampalam, W., Gregg, P., & Gregory, M. (2001). Introduction: unemployment scarring. The Economic Journal, 111, F577–F584.

Autor, D., Kostøl, A., Mogstad, M., & Setzler, B. (2019). Disability benefits, consumption insurance, and household labor supply. American Economic Review, 109, 2613–2654.

Autor, D. H., Duggan, M., Greenberg, K., & Lyle, D. S. (2016). The impact of disability benefits on labor supply: Evidence from the VA’s disability compensation program. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 8, 31–68.

Ayhan, S. H. (2018). Married women’s added worker effect during the 2008 economic crisis–The case of Turkey. Review of Economics of the Household, 16, 767–790.

Bentolila, S., & Ichino, A. (2008). Unemployment and consumption near and far away from the Mediterranean. Journal of Population Economics, 21, 255–280.

Blundell, R., Pistaferri, L., & Saporta-Eksten, I. (2016). Consumption inequality and family labor supply. American Economic Review, 106, 387–435.

Borghans, L., Gielen, A. C., & Luttmer, E. F. P. (2014). Social support substitution and the earnings rebound: evidence from a regression discontinuity in disability insurance reform. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 6, 34–70.

Bredtmann, J., Otten, S., & Rulff, C. (2018). Husband’s unemployment and wife’s labor supply: the added worker effect across Europe. ILR Review, 71, 1201–1231.

Calonico, S., Cattaneo, M. D., & Titiunik, R. (2014). Robust data-driven inference in the regression-discontinuity design. The Stata Journal, 14, 909–946.

Cammeraat, E., Jongen, E., & Koning, P. (2023). The added-worker effect in the Netherlands before and during the great recession. Review of Economics of the Household, 21, 217–243.

Campolieti, M. (2004). Disability insurance benefits and labor supply: Some additional evidence. Journal of Labor Economics, 22, 863–889.

Cullen, J. B., & Gruber, J. (2000). Does unemployment insurance crowd out spousal labor supply? Journal of Labor Economics, 18, 546–572.

De Jong, P., Lindeboom, M., & van der Klaauw, B. (2011). Screening disability insurance applications. Journal of the European Economic Association, 9, 106–129.

Deshpande, M. (2016). The effect of disability payments on household earnings and income: Evidence from the SSI children’s program. Review of Economics and Statistics, 98, 638–654.

Deuchert, E., & Eugster, B. (2019). Income and substitution effects of a disability insurance reform. Journal of Public Economics, 170, 1–14.

Duggan, M., Rosenheck, R., & Singleton, P. (2010). Federal policy and the rise in disability enrollment: Evidence for the veterans affairs’ disability compensation program. The Journal of Law and Economics, 53, 379–398.

Fadlon, I., & Nielsen, T. H. (2021). Family labor supply responses to severe health shocks: evidence from Danish administrative records. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 13, 1–30.

Fevang, E., Hardoy, I., & Røed, K. (2017). Temporary disability and economic incentives. The Economic Journal, 127, 1410–1432.

García-Gómez, P., van Kippersluis, H., O’Donnell, O., & van Doorslaer, E. (2012). Long-term and spillover effects of health shocks on employment and income. The Journal of Human Resources, 48, 873–909.

García-Mandicó, S., García-Gómez, P., Gielen, A., & O’Donnell, O. (2021). The impact of social insurance on spousal labor supply: Evidence from cuts to disability benefits in the Netherlands. Mimeo, Erasmus University Rotterdam.

Godard, M., Koning, P., & Lindeboom, M. (2022). Application and award responses to stricter screening in disability insurance. The Journal of Human Resources, 57, 1120–11323R1.

Gruber, J. (2000). Disability insurance benefits and labor supply. Journal of Political Economy, 108, 1162–1183.

Hahn, J., Todd, P., & Van der Klaauw, W. (2001). Identification and estimation of treatment effects with a regression-discontinuity design. Econometrica, 69, 201–209.

Hainmueller, J. (2012). Entropy balancing for causal effects: a multivariate reweighting method to produce balanced samples in observational studies. Political Analysis, 20, 25–46.

Halla, M., Schmieder, J., & Weber, A. (2020). Job displacement, family dynamics, and spousal labor supply. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 12, 253–287.

Haller, A., Staubli, S., & Zweimüller, J. (2023). Designing disability insurance reforms: Tightening eligibility rules or reducing benefits. Econometrica Forthcoming.

Hullegie, P., & Koning, P. (2018). How disability insurance reforms change the consequences of health shocks on income and employment. Journal of Health Economics, 62, 134–146.

Imbens, G. W. (2004). Nonparametric estimation of average treatment effects under exogeneity: A review. Review of Economics and Statistics, 86, 4–29.

Imbens, G. W., & Lemieux, T. (2008). Regression discontinuity designs: A guide to practice. Journal of Econometrics, 142, 615–635.

Jolly, N. A., & Theodoropoulos, N. (2023). Health shocks and spousal labor supply: An international perspective. Journal of Population Economics, 36, 973–1004.

Kantarcı, T., van Sonsbeek, J.-M., & Zhang, Y. (2023). The heterogenous impact of stricter criteria for disability insurance. Health Economics, 31, 1898–1920.

Karlström, A., Palme, M., & Svensson, I. (2008). The employment effect of stricter rules for eligibility for DI: Evidence from a natural experiment in Sweden. Journal of Public Economics, 92, 2071–2082.

Koning, P., & Lindeboom, M. (2015). The rise and fall of disability insurance enrollment in the Netherlands. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 29, 151–172.

Koning, P., & van Sonsbeek, J.-M. (2017). Making disability work? The effects of financial incentives on partially disabled workers. Labour Economics, 47, 202–215.

Koning, P., & van Vuuren, D. (2007). Hidden unemployment in disability insurance. Labour, 21, 611–636.

Kostøl, A. R., & Mogstad, M. (2014). How financial incentives induce disability insurance recipients to return to work. American Economic Review, 104, 624–655.

Low, H., & Pistaferri, L. (2015). Disability insurance and the dynamics of the incentive insurance trade-off. American Economic Review, 105, 2986–3029.

Lundberg, S. (1985). The added worker effect. Journal of Labor Economics, 3, 11–37.

Maloney, T. (1987). Employment constraints and the labor supply of married women: A reexamination of the added worker effect. The Journal of Human Resources, 22, 51–61.

Maloney, T. (1991). Unobserved variables and the elusive added worker effect. Economica, 58, 173–187.

Marie, O., & Vall Castello, J. (2012). Measuring the (income) effect of disability insurance generosity on labour market participation. Journal of Public Economics, 96, 198–210.

Moore, T. J. (2015). The employment effects of terminating disability benefits. Journal of Public Economics, 124, 30–43.

Mullen, K. J., & Staubli, S. (2016). Disability benefit generosity and labor force withdrawal. Journal of Public Economics, 143, 49–63.

OCTAS. (2023). Beoordeling van het arbeidsongeschiktheidsstelsel. Tech. Rep. https://open.overheid.nl/documenten/0e1fea0f-78ce-4a06-ba7b-917f88c9ec37/file.

OECD. (2018). Public spending on incapacity. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Prinz, D. & Ravesteijn, B., (2020). Employer responsibility in disability insurance: Evidence from the Netherlands. Mimeo, Harvard University. https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/dprinz/files/employers_di_paper.pdf.