Abstract

Enterprises play a vital role in emergency management, but few studies have considered the strategy choices behind such participation or the collaborative relationship with the government. This study contended that enterprises have at least three strategies regarding emergency management: non-participation, short-term participation, and long-term participation. We constructed a two-stage evolutionary game model to explore the behavioral evolution rules and evolutionary stability strategies of the government and enterprises, and employed numerical simulation to analyze how various factors influence the strategy selection of the government and enterprises. The results show that if and only if the utility value of participation is greater than 0, an enterprise will participate in emergency management. The evolutionary game then enters the second stage, during which system stability is affected by a synergistic relationship between participation cost, reputation benefit, and government subsidies, and by an incremental relationship between emergency management benefit, government subsidies, and emergency training cost. This study provides a new theoretical perspective for research on collaborative emergency management, and the results provide important references for promoting the performance of collaborative emergency management.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The mounting frequency and intensity of various emergencies are placing increased pressure on emergency management (Bosomworth et al. 2017), and the traditional government-centered system struggles to respond effectively. To improve the market mechanism and give full play to its efficiency, professionalism, and competitiveness, market participation in emergency management is imperative (Nan et al. 2022). In many countries, enterprises, non-profit organizations, and residents have played an important role in such work. The general trend of emergency management worldwide has been to advocate collaboration between governments, social organizations, enterprises, and the residents (Kong and Sun 2021; Fan et al. 2022).

Collaborative emergency management (CEM) has been defined as joint activity of two or more stakeholders that work together in pursuit of greater public good. It aims to eliminate wasted resources and efforts via communication, coordination, and interoperability (Kapucu et al. 2010). With the complexity of emergencies continues to increase, the success of emergency management becomes increasingly depending on effective collaboration (Oh et al. 2014). The September 11 attacks in 2001 and Hurricane Katrina in 2005 have been followed by a significant increase in the role of social forces in emergency management (Lv 2017). In particular, private enterprises have made great contributions by enhancing their advantages in capital, technology, and equipment. For example, Walmart and Home Depot implemented effective relief efforts in responding to Hurricane Katrina, combining proactivity with logistic expertise (Wang et al. 2014). During the Covid-19 pandemic, Meituan provided people with many kinds of food, necessities, medicines, epidemic prevention and disinfection supplies, and other errand services, thereby deploying its professional capabilities to provide necessary guarantees for people’s live (Zhang 2021). According to the 2020 Meituan Delivery Action Report against COVID-19, Meituan’s order volume reached 3.96 million during the lockdown of Wuhan, with 54.1% of Meituan riders delivering orders to hospitals. Meituan took the lead in launching a “contactless delivery” service, which played an important role in avoiding contact infection. Each enterprise has unique advantages, and the strong “joint force” they can form is increasingly important when dealing with emergencies, effectively mitigating inadequacies of government provision in emergency management.

The above illustrates that enterprises have become an important actor in emergency management. Government failures in emergency response and the greater efficiency of the private sector further reflect enterprises’ important functions (Linnenluecke and McKnight 2017). However, enterprises participating in emergency management continue to self-organize, rather than being included in the government response system (Zhang and Tong 2015). Previous studies have focused mostly on the emergency management capability of public organizations, such as the government and schools (Shi 2012; Shah et al. 2018), while giving little attention to private organizations. In particular, the greater efficiency of enterprises’ participation in emergency management through the market mechanism has scarcely been explored. Therefore, this study aimed to analyze the strategy choices and game relationship between local governments and private enterprises, and to explore what incentives promote CEM performance. Our findings will have important theoretical and practical significance for promoting the establishment of a sustainable, effective CEM system and improving capabilities.

2 Literature Review

This section introduces related works about CEM and evolutionary game theory, discusses gaps in the literature, and explains why we used evolutionary game method and system dynamics (SD) simulation in this study.

2.1 Related Works on Collaborative Emergency Management (CEM)

Due to the increasing frequency and severity of large-scale disasters worldwide, since the beginning of the twenty-first century, particularly following the September 11 attacks in 2001, multi-agent CEM for cross-border and major crises has become a hot topic among scholars (Ansell et al. 2010; Hart 2013). Multi-agent collaboration in emergency management has three main aspects: collaboration between the government, the market, and social organizations (Diehlmann et al. 2021); collaboration between governments at different levels and in different regions (vertical and horizontal) (Li 2017); and collaboration between different functional agencies at the same government level (Bennett 2018). Previous studies focused mainly on the synergistic relationship between government emergency management departments and social organizations. For example, Tau et al. (2017) analyzed the CEM between different countries in the Southern African Development Community (SADC). Olszewski and Siebeneck (2021) discussed the nature of CEM between different levels of government in the United States, and proposed a framework visualizing collaboration as a trust-building and outcome cycle. Chen et al. (2019b) revealed the functions of social organizations in natural hazard-related disasters’ emergency relief, and analyzed their role orientation in the emergency management network. Elsewhere, the role of emerging technologies in promoting CEM capabilities has also attracted widespread scholarly attention. For example, Wang and Chen (2022) clarified the possibility of using blockchain technology to improve the efficiency of multi-agent CEM with respect to information sharing, supervision, and reward/punishment. Xiong and Xue (2023) analyzed the feasibility of using blockchain to improve the performance of emergency material collaborative transportation. Gupta et al. (2022) put forward an evidence-based framework that emphasizes the role of artificial intelligence and cloud-based collaboration platforms in emergency management.

In terms of enterprises’ participation in emergency management, previous studies have mainly focused on enterprises’ own emergency management capability and role. For example, Li et al. (2021) explored the effect of personal initiative on enterprise emergency management capability, seeking an evidential basis for proposing effective measures to improve emergency management ability. Ai and Zhang (2019) studied the storage and distribution problem of maritime emergency supplies under the CEM of the government and enterprises using a two-stage optimization location model. Xie et al. (2022) studied the decision-making and cooperation problems for emergency medical supplies considering corporate social responsibility with the government, manufacturers, and retailers. However, few scholars have examined how enterprises can participate more effectively, or the CEM relationship between enterprises, governments, and other participants such as social organizations and residents.

2.2 Evolutionary Game Theory

Evolutionary games have occupied an increasing share of game theory literature in recent years. Evolutionary game is a combination of game theory and dynamic evolutionary process analysis, originated from the study of biological evolutionary process in theory of evolution. In an evolutionary game involving any form of strategic interaction, higher payoff strategies tend to replace lower payoff strategies over time, but there is some inertia, and players do not systematically attempt to influence other players’ future decisions. Friedman (1998) indicated that like the traditional game, an evolutionary game model must have a game framework, including hypothesis, structure, and rules of the game, and the evolutionary game process is always carried out under such a framework.

Evolutionary game has become a classical method for studying the multi-agent collaborative governance mechanism, and is widely used in research on the formation and evolution process of social habits, rules, and institutions (Liu et al. 2015; Semasinghe et al. 2015). In the field of organizational cooperation, evolutionary game theory has been widely used to various problems, such as industry-university-research cooperation (Cao and Li 2020), market-supervision cooperation (Lu et al. 2018), environmental governance cooperation (Chen et al. 2019a), public goods game (Wang et al. 2013), and sustainable humanitarian supply chains (Li et al. 2019). It is also widely applied in the research of CEM involving multiple stakeholders. For example, Du and Qian (2016) used evolutionary game theory to explore the interactions between government and non-profit organizations in emergency mobilization within China. Shao et al. (2022) established an evolutionary game model for the collaborative governance of construction waste with multi-agent participation, and integrated system dynamics (SD) to simulate and analyze the system’s strategy selection. Fan et al. (2021) analyzed interactions among the behavioral strategies of government, community, and citizens amid public health emergencies by combining evolutionary game method and SD. Liu et al. (2021) examined the cooperation relationship between government and social organizations in emergency management by adopting evolutionary game theory and simulation analysis. Evidently, as an effective method to study the dynamic problems of complex systems, SD simulation is often combined with evolutionary game theory to better explore the strategy evolution mechanisms of multiple stakeholders in the CEM system.

Although the importance of enterprise participation in emergency management has been widely recognized, there is little research on how they effectively collaborate with the government. Most game studies on CEM have focused on the cooperation between local governments, or between governments and social organizations, while few have investigated collaboration between governments and enterprises. Research on collaborative governance of emergencies between the government and enterprises mainly analyzed the challenges of enterprise participation in emergency management in a theoretical framework, or illustrated the importance of their participation through case studies. For example, Puliga and Ponta (2021) investigated the fast innovation reactions of different enterprises (including Isinnova, Grafica, Campari Group, Caracol, Ellamp, Distillerie Silvio Carta, and Mares) to the Covid-19 emergency; their findings show that with the ability to rapidly reconfigure process and innovation, these enterprises have made important contributions to early recovery from Covid-19 by providing needed supplies. Therefore, this study explored the strategy choices and influencing factors of enterprises and governments in CEM using the combination of evolutionary game theory and SD simulation. This method should better explain the interaction between collaborating governments and enterprises.

3 Methods

Evolutionary game theory posits that players are subject to bounded rationality, and uses the concept of natural selection (rather than profit maximization) for economic analysis. At the beginning of the game, both players of the game cannot determine their optimal strategies, but find the optimal strategy combination through continuous imitation, trial, and error and learning, finally reach a stable state (Levine and Pesendorfer 2007). One of the key concepts in evolutionary game theory is evolutionary stable strategy (ESS), which is when the vast majority of individuals in the population choose a certain strategy; the group that chooses the mutation strategy cannot invade the group that contains the vast majority of individuals as it includes fewer individuals (Wang et al. 2022).

When analyzing multi-variable nonlinear complex systems, SD can not only solve the modeling problem of complex systems, but also perform quantitative coordination and optimization of the relationships among system elements under the overall framework. System dynamics model describes the causality and feedback relationship between system elements through a casual flow diagram (Fan et al. 2021), and carries out simulation experiments by establishing computer-based models. Specifically, based on evolutionary game modeling, this study used a SD model to simulate the evolutionary game process and the dynamic equilibrium results of CEM between governments and enterprises, and analyze the effect of various factors on the ESS.

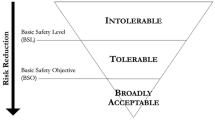

Nearly all previous studies are based on a binary opposition perspective, such as “(not) governance,” “(not) participation,” “(not) incentive,” and “(not) coordination.” In practice, however, enterprises have at least three strategies of non-participation, short-term participation, and long-term participation with respect to emergency management, while governments also have at least three strategies of non-incentive, short-term incentive, and long-term incentive. In other words, the classical evolutionary game method in existing studies cannot appropriately describe enterprise strategy choice regarding emergency management. Furthermore, in a traditional evolutionary game, the matrix is usually static, and all players select their respective strategies concurrently, making it difficult to explain some social and economic phenomena with successive decision making in real society. The two-stage game model is an effective method to analyze multi-agent interaction, multi-element collaboration, and multi-stage progression. In the emergency management process, the enterprises have priority in choosing whether or not they will participate; accordingly, the choice behavior of both players has the order of priority, but the game players can see one another’s choices before choosing their own strategies. Therefore, in the game of emergency management between the government and enterprises, it is more appropriate to use a two-stage game method. Based on previous studies involving two-stage games (Petrosyan et al. 2016; Gao et al. 2017; Tang et al. 2021), we constructed a two-stage evolutionary game framework for emergency management (Fig. 1), seeking to provide explanatory ideas for the evolution of government-enterprise CEM.

As shown in Fig. 1, during the process of two-stage evolutionary game, player 1 makes decisions first, i and j refer to two strategies of player 1 in the first stage. If player 1 adopts strategy i, the original benefit of player 1 and player 2 remains unchanged, which are Π1 and Π2 respectively, and then the game ends. If player 1 selects strategy j, the game enters the second stage. In this stage, player 1 has two strategies, p and q, player 2 has two strategies, m and n, and the evolutionary game system has four strategy combinations: (p, m), (p, n), (q, m), and (q, n); and the benefit of player 1 and player 2 in each situation is (Πp, Πm), (Πp, Πn), (Πq, Πm), and (Πq, Πn), respectively. In addition, the benefit of both sides is affected by the strategies of the other side, and they find their own optimal strategies in the process of constant gaming, and finally reach a stable state.

4 Construction of a Two-Stage Evolutionary Game Model

This section details the construction of a two-stage evolutionary game model for CEM between the government and enterprises, calculates the system’s ESS, and tests the model stability.

4.1 Game Scenario

From the rational choice perspective, collaboration between the government and enterprises is premised on both sides recognizing the possibility of benefit. On the one hand, the government plays a key role in effectively promoting enterprises’ participation in emergency management, whether by formulating preferential tax policies or providing subsidies (Luo et al. 2022). Its aims in this endeavor are to improve emergency management capability, quickly and effectively respond to various emergencies, reduce disaster losses, maximize the protection of people’s lives and property, and maintain social security and stability. On the other hand, enterprises’ participation in emergency management can provide enormous social benefit by reducing pressure on the government, while also enhancing their corporate image (Hamann et al. 2020). For example, Lüttenberg et al. (2022) indicated that enterprises’ involvement in emergency management is general highly valued by consumers, leading to increase willingness to choose their products and services. In addition, active participation in emergency management is also an important part of corporate social responsibility (Johnson et al. 2011). Studies have shown that fulfilling social responsibility obligations can also lead to growth and sustainability of an enterprise’s business. Li et al. (2023) indicated that during Covid-19, enterprises involved in emergency hospital construction and donations had higher excess return rates.

Enterprises’ participation strategies are also affected by participation cost and stakeholder behaviors (Zhang and Kong 2022).First, participating in emergency management inevitably involves extra cost, and as a limited rational subject, if the cost of participating is greater than the benefit, the enterprise will not choose to participate. Second, the government plays an important role in promoting enterprises’ participation in emergency management (Luo et al. 2022). Government subsidies can reduce the cost of participation, and thereby improve the willingness of enterprises to participate in emergency management. However, as the subject of bounded rationality, the government will choose different incentive strategies according to different participation strategies of enterprises to maximize the performance of emergency management. The differences in motivation and preference of the government and enterprises make it difficult for them to construct long-term collaborative relationships in emergency management.

Furthermore, in the CEM of the government and enterprises, the latter retain the right to choose whether to participate, and only if they do so can the CEM mechanism be produced. In the process of collaboration, the evolution of the government and enterprise strategies has a mutually promoting mechanism, and both sides seek the optimal strategy combination through continuous evolution, imitation, and learning, eventually reaching a stable state. Therefore, in this study the collaborative relationships were explored based on the perspective of evolutionary game theory, aiming at seeking effective measures to improve the performance of CEM between the government and enterprises.

4.2 Assumptions and Parameters

Our proposed model is based on the following assumptions:

-

(1)

There are only two players in the evolutionary game system—local government and private enterprises (referred to as “government” and “enterprises”).

-

(2)

Both the government and enterprises are bounded rational. Due to information asymmetry, they have limited abilities in rational cognition, analytical reasoning, and decision making.

-

(3)

The government will always adopt active emergency management strategies toward social stability, security, and sustainable development.

-

(4)

Enterprises are free to choose whether or not to participate in emergency management, respectively defined as “participation” and “non-participation.” The game will enter the second stage if and only if the enterprise chooses the “participation” strategy in the first stage.

-

(5)

In the second stage, enterprises have two strategies: “short-term participation” and “long-term participation.” Short-term participation refers to the temporary and random participation behavior of enterprises in emergency management, which often occurs in the emergency rescue stage (Yang and Zhang 2018). Long-term participation first refers to the enterprises’ participation in the whole process of emergency management, including prevention, preparation, response, and recovery. In addition, long-term participation means that enterprises formally become partners of the government and effectively integrate with the government’s emergency forces. Long-term participation of enterprises will contribute more to emergency management, but it also means more cost. Correspondingly, the government also has two strategies to encourage enterprise participation in emergency management: “short-term incentive” and “long-term incentive.” Compared with short-term incentive, long-term incentive means that the government provides emergency training to enterprises participating in emergency management to improve their participation efficiency. In addition, long-term incentive aims to reduce the participation cost of enterprises through government subsidies, thereby enhance their willingness and capabilities to continue to participate. The parameters of this evolutionary game model are defined and described in Table 1.

4.3 Construction and Analysis of the Two-Stage Evolutionary Game Model

According to the two-stage evolutionary game framework presented in Fig. 1 and the special nature of emergency management, this study took the government and enterprises as the players in dynamic and static games between the two sides and constructed a pay-off matrix of two-stage evolutionary game with collaborative relationships in emergency management (Fig. 2).

4.3.1 Analysis of the First Stage

Whether enterprises should participate in emergency management is no longer a question. The real question is what roles enterprises should play and how to improve emergency management capabilities by establishing effective public-private collaboration mechanisms. Therefore, we analyzed the motivation of enterprises to participate and its influencing factors in the first stage of this evolutionary game model. In the process of emergency management, enterprises have the option of priority, the participation of enterprises can be regarded as event A, and the probability that event A occurs is x. Then \(P\left( A \right) = x, \, P\left( {\overline{A}} \right) = 1 - x\).

Previous studies have shown that enterprise participation in emergency management results from many influencing and decisive factors (Lu and Zhu 2022; Luo et al. 2022; Zhang and Kong 2022). First, according to the theory of planned behavior (Luiza et al. 2020), some influencing factors enhance enterprises’ willingness to participate, thus indirectly affecting their strategy choices regarding participation. Specifically, influencing factors comprise internal enterprise factors and external environmental factors. The former includes emergency resources, experience, and capabilities possessed by enterprises themselves, while the latter are external, particularly participation policies, emergency culture, and other participants. As an economic stakeholder of limited rationality, enterprises do not inevitably participate in emergency management even if their willingness to do so improves. The interaction mechanism of influencing factors on enterprises’ participation strategies is represented by the dotted line in Fig. 3.

Evolution stability in stage 1. \(\mathcal{U}\left(\upomega , \fancyscript{c}\right)=\upomega -\fancyscript{c}\) refers to the utility function of enterprises in the first stage, \(\upomega \) refers to the extra benefit of enterprises’ participation in emergency management, \(\fancyscript{c}\) refers to the extra cost of enterprises’ participation.

Second, decisive factors include extra benefit (\(\omega\)) and cost (c) of participation for enterprises, which have a more significant and direct impact on their decision on whether to participate (Shi et al. 2023). Therefore, whether enterprises participate in emergency management depends ultimately on the utility function of participation, which can be expressed as \({\mathcal{U}}\left( {\omega , c} \right) = \omega - c\). If and only if \({\mathcal{U}}\left( {\omega , c} \right) = \omega - c > 0,{\text{ then }}c = 1\), and the enterprise will choose participation strategy, with the evolutionary game then entering the second stage. Otherwise, \(x = 0,\) and the enterprise chooses not to participate because the cost outweighs the benefit; correspondingly, the government will choose the non-incentive strategy (Fig. 3).

4.3.2 Analysis of the Second Stage

Incentives from the government have a significant impact on enterprise participation in emergency management (Luo et al. 2022). They include a series of targeted policies, providing participation conveniences, and benefit such as financial rewards and technical or policy support, which are conductive to enterprises’ own economic development. Therefore, the second stage focuses mainly on sustainable collaboration between the government and enterprises in emergency management, considering the choice of government incentives and the choice of enterprises’ participation strategy, and exploring their behavior evolution rules and stability strategies.

Under the premise of bounded rationality, the evolutionary game of CEM between the government and enterprises is a process of mutual learning and dynamic self-adaptation. Therefore, we used the replicated dynamic equation to simulate their decision-making process. The benefit of the enterprises choosing the long-term participation strategy is \({E}_{E1}\):

The benefit of the enterprises choosing the short-term participation strategy is \({E}_{E2}\):

Then the average expected revenue is recorded as \({E}_{E}\):

The replicated dynamic equation of enterprises choosing the long-term participation strategy is:

The benefit of the government choosing the long-term incentive strategy is \({E}_{G1}\):

The benefit of the government choosing the short-term incentive strategy is \({E}_{G2}\):

Then the average expected revenue is recorded as \({E}_{G}\):

The replicated dynamic equation of the government choosing the long-term incentive strategy is:

Therefore, the two-dimensional dynamic system of the evolutionary game of CEM between the government and enterprise is:

Let \({{d_{y} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{d_{y} } {d_{t} }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {d_{t} }} = 0, \, {{d_{z} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{d_{z} } {d_{t} }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {d_{t} }} = 0\) then on the plane \({\mathcal{N}} = \left\{ {\left( { z,y} \right); \, 0 \le z,y \le 1} \right\}\), this system has five equilibrium points: (0, 0), (0, 1), (1, 0), (1, 1), and (\(y_{t}^{*}\),\(z_{t}^{*}\)). Among them:

The stability of the equilibrium point in the differential system can be calculated by analyzing the local stability of the Jacobi matrix:

Then the determinant of the Jacobi matrix can be calculated as follows:

Next, the trace of the Jacobi matrix can be calculated thus:

According to the evolutionary game theory, if \(\mathcal{D}\fancyscript{e}\fancyscript{t}\left(\mathcal{J}\right)>0\) and \(\mathcal{T}\fancyscript{r}\left(\mathcal{J}\right)<0\) are satisfied at equilibrium points of the replicated dynamic equations, they constitute ESS of the system. For each equilibrium point, the determinant and trace of the system are shown in Table 2.

According to the above hypothesis, as well as the determinant and trace of equilibrium points in Table 2, the local stability of this evolutionary game system can be judged. Specifically:

-

(1)

If \(\alpha \rho +\theta \fancyscript{r}+{\mathcal{C}}_{E1}-{\mathcal{C}}_{E2}<0\) and \(\mathrm{\kappa \rho }-\fancyscript{d}<0\), then (0, 0) is ESS of the system.

-

(2)

If \(\alpha \rho +\theta \fancyscript{r}+{\mathcal{C}}_{E1}-{\mathcal{C}}_{E2}+\mathcal{S}<0\mathrm{ and }\kappa \rho -\fancyscript{d}>0\), then (1, 0) is ESS of the system.

-

(3)

If \(\alpha \rho +\theta \fancyscript{r}+{\mathcal{C}}_{E1}-{\mathcal{C}}_{E2}>0\) and \(\kappa \rho -\fancyscript{d}-\mathcal{S}<0\), then (0, 1) is ESS of the system.

-

(4)

If \(\alpha \rho +\theta \fancyscript{r}+{\mathcal{C}}_{E1}-{\mathcal{C}}_{E2}+\mathcal{S}>0\) and \(\kappa \rho -\fancyscript{d}-\mathcal{S}>0\), then (1, 1) is ESS of the system.

-

(5)

In any case, the equilibrium point (\({\fancyscript{y}}_{\fancyscript{t}}^{*}\),\({\fancyscript{z}}_{\fancyscript{t}}^{*}\)) cannot be an ESS of the system; and if \({\fancyscript{z}}_{\fancyscript{t}}^{*}{\fancyscript{y}}_{\fancyscript{t}}^{*}\left(1-{\fancyscript{z}}_{\fancyscript{t}}^{*}\right)\left(1-{\fancyscript{y}}_{\fancyscript{t}}^{*}\right){\mathcal{S}}^{2}<0\), then (\({\fancyscript{y}}_{\fancyscript{t}}^{*}\),\({\fancyscript{z}}_{\fancyscript{t}}^{*}\)) is saddle point of the system.

4.3.3 Model Stability Test

The replicated dynamic equation needs to meet stability requirements to ensure it will not significantly change due to slight shifts in parameters. We therefore tested stability before numerical analysis using the stability analysis method suggested by Wei et al. (2012) and Sun et al. (2023): the sensitivity index is calculated by changing 10% of key factors; and if the sensitivity index is less than 1, the model is stable. The sensitivity index is calculated as follows:

where t denotes time; \({S}_{p}\) refers to the sensitivity of system state P to parameter U; \({P}_{t}\) represents the system state at time t; \({U}_{t}\) is the value of the system parameter at time t; \(d{P}_{t}\) and \(d{U}_{t}\) respectively denote the values of changes in system state P and parameter U at time t; n is the number of sensitivity test points, and n = 2. We tested the sensitivity of some key model parameters (including \(\alpha ,\) \(\theta , { \mathcal{C}}_{E1}, { \mathcal{C}}_{E2},\upkappa ,\uprho , \fancyscript{d}, \fancyscript{r}, and \mathcal{S}\)) by changing the value of each by +10% and −10% respectively. As shown by the results in Fig. 4, all the sensitivity indices are less than 1, which indicates that the model passed the stability test.

5 Numerical Analysis

This section analyzes the system’s evolution path under different situations by adopting SD simulation methods, as well as the effects of cost difference, government subsidies, reputation benefit, and training cost on the evolutionary game paths of long-term participation and short-term participation, thereby further exploring the collaboration mechanism between enterprises and governments.

5.1 Numerical Analysis Under Different Situations

To show the dynamic evolution process of enterprise and government strategy selection more intuitively, we adopted numerical simulation in this study, using MATLAB to simulate the dynamic evolution trajectory from initial point to equilibrium point in several situations. The simulation results are shown in Fig. 5.

-

Situation (a): When \(\alpha \rho +\theta \fancyscript{r}<{\mathcal{C}}_{E2}-{\mathcal{C}}_{E1}\), \(\mathrm{\kappa \rho }<\fancyscript{d}\), and \(\alpha =0.2, \theta =0.3, {\mathcal{C}}_{E1}=10, {\mathcal{C}}_{E2}=16, \kappa =0.4, \rho =5, \fancyscript{d}=4, \fancyscript{r}=10, \mathcal{S}=1,\) the evolution step of the system is shown in Fig. 5a. In this situation, the incremental benefit for the government to pay for training an enterprise in emergency management is disproportionate to the training cost when pursuing a long-term incentive strategy. Consequently, the government is unwilling to pay training cost for enterprises and tends to pursue a short-term incentive strategy. Meanwhile, the sum of incremental emergency management benefit and reputation benefit for enterprises from long-term participation is outweighed by the extra cost paid. Therefore, as bounded rational stakeholders, enterprises will choose the short-term participation strategy to maximize self-interest. Finally, the evolution result of the system converges to (0, 0), and the ESS is {short-term participation, short-term incentive}.

-

Situation (b): When \(\alpha \rho +\theta \fancyscript{r}+\mathcal{S}<{{\mathcal{C}}_{E2}-\mathcal{C}}_{E1}, \kappa \rho >\fancyscript{d}\), and \(\alpha =0.5, \theta =0.5, {\mathcal{C}}_{E1}=10, {\mathcal{C}}_{E2}=17, \kappa =0.6, \rho =5, \fancyscript{d}=2, \fancyscript{r}=10, \mathcal{S}=2,\) the evolution step of the system is shown in Fig. 5b. Under this situation, the sum of the increase of emergency management benefit, reputation benefit, and government subsidies obtained by choosing long-term participation strategy is outweighed by the incremental cost of participation. Consequently, enterprises will choose short-term participation strategy. For the government, the incremental benefit of enterprises supporting emergency management after training exceeds the training cost paid by the government. Therefore, the government will choose the long-term incentive strategy, and the evolution result of the system finally converges to (0, 1). In this situation, the ESS is {short-term participation, long-term incentive}.

-

Situation (c): When \(\alpha \rho +\theta \fancyscript{r}>{\mathcal{C}}_{E2}-{\mathcal{C}}_{E1}\), \(\kappa \rho <\fancyscript{d}+\mathcal{S}\), and \(\alpha =0.4, \theta =0.3, {\mathcal{C}}_{E1}=10, {\mathcal{C}}_{E2}=18, \kappa =0.7, \rho =5, \fancyscript{d}=2, \fancyscript{r}=10, \mathcal{S}=2,\) the evolution step of the system is shown in Fig. 5c. In this situation, the sum of emergency management benefit and reputation benefit exceeds the incremental cost of participation, leading enterprises to choose long-term participation strategy regardless of which incentive strategy is pursued by the government. For the government, however, the subsidies and emergency management training cost paid to enterprises pursuing long-term participation exceed the incremental benefit for emergency management brought by trained enterprises. Therefore, government will pursue the short-term incentive strategy, and the evolution result of the system finally converges to (1, 0). In this situation, the ESS is {long-term participation, short-term incentive}.

-

Situation (d): When \(\alpha \rho +\theta \fancyscript{r}+\mathcal{S}>{{\mathcal{C}}_{E2}-\mathcal{C}}_{E1}\), \(\kappa \rho >\fancyscript{d}+\mathcal{S}\), and \(\alpha =0.5, \theta =0.6, {\mathcal{C}}_{E1}=10, {\mathcal{C}}_{E2}=16, \kappa =0.8, \rho =5, \fancyscript{d}=1, \fancyscript{r}=10, \mathcal{S}=1,\) the evolution step of the system is shown in Fig. 5d. This situation entails that the incremental benefit of enterprises’ participation in emergency management exceeds the training cost and subsidies paid by the government. Consequently, whichever strategy enterprises choose, the government will pursue long-term incentive strategy. For enterprises, the sum of incremental emergency management benefit, reputation benefit, and government subsidies exceeds the extra cost of pursuing long-term participation. Therefore, enterprises will choose the long-term participation strategy, and the evolution result of the system finally converges to (1, 1), the ESS under this situation is {long-term participation, long-term incentive}.

5.2 Numerical Analysis of Parameter Variation

With the initial probability unchanged, we analyzed the effect of each parameter on the evolutionary game path. The results of the numerical analysis are shown in Fig. 6.

5.2.1 Effect of Enterprise Participation Cost on Evolution Results

Other parameters are: \(\alpha =0.6, \theta =0.4,\upkappa =0.6,\uprho =5, \fancyscript{d}=6, \fancyscript{r}=10, \mathcal{S}=15.\) The initial probability is \({\fancyscript{z}}_{0}=0.5 \mathrm{and }{\fancyscript{y}}_{0}=0.5\); the incremental cost of enterprises choosing long-term versus short-term participation is \(\Delta \fancyscript{c}={{\mathcal{C}}_{E2}-\mathcal{C}}_{E1}\), varying between [0, 10]; and the evolution result of the system is shown in Fig. 6a. The result of the numerical analysis shows that if \(0\le\Delta \fancyscript{c}\le 6\), an enterprise’s ESS converges to long-term participation, and the evolution speed decreases as \(\Delta \fancyscript{c}\) rises; if \(\Delta \fancyscript{c}\ge 8\), then the enterprises’ ESS converges to short-term participation, and the evolution speed increases as \(\Delta \fancyscript{c}\) rises. Compared with short-term participation, enterprises are willing to adopt long-term participation strategy when the cost increment of long-term participation is small. On the contrary, as the cost increment of long-term participation increases gradually, enterprises will adopt short-term participation strategy.

5.2.2 Effect of Reputation Benefit on Evolution Results

Other parameters are: \(\alpha =0.6, \theta =0.4,\upkappa =0.6,\uprho =5, \fancyscript{d}=6, {{\mathcal{C}}_{E2}=20, \mathcal{C}}_{E1}=10, \mathcal{S}=15\). The initial probability is \({\fancyscript{z}}_{0}=0.5 \mathrm{and }{\fancyscript{y}}_{0}=0.5\); the value of the reputation benefit \(\fancyscript{r}\) obtained by enterprises for participating in emergency management varies within the range [0, 20], and the evolution result of the system is shown in Fig. 6b. The result shows that if \(0\le \fancyscript{r}\le 15\), the enterprise’s ESS converges to short-term participation, and the evolution speed decreases as \(\fancyscript{r}\) rises; If \(\fancyscript{r}\ge 20\), the enterprise’s ESS converges to long-term participation, and the evolution speed increases as \(\fancyscript{r}\) rises. This indicates that increasing reputation benefit incentivize enterprises to pursue long-term participation; otherwise, they will adopt the short-term participation strategy. In other words, reputation benefit has a positive impact on enterprises’ strategy choice.

5.2.3 Effect of Government Subsidies on Evolution Results

Other parameters are: \(\alpha =0.6, \theta =0.4,\upkappa =0.6,\uprho =15, \fancyscript{d}=6, {{\mathcal{C}}_{E2}=20, \mathcal{C}}_{E1}=10, \fancyscript{r}=10\). The initial probability is \({\fancyscript{z}}_{0}=0.5 \mathrm{and }{\fancyscript{y}}_{0}=0.5\); the value of government subsidies \(\mathcal{S}\) varies within the range [0, 10]; and the evolution result of the system is shown in Fig. 6c. The result shows that if \(0\le \mathcal{S}\le 2\), the government’s ESS converges to long-term participation, and the evolution speed decreases as \(\mathcal{S}\) rises; If \(\mathcal{S}\ge 4\), the government’s ESS converges to short-term participation, and the evolution speed increases as \(\mathcal{S}\) rises. For enterprises, their ESS converges to long-term participation, and the evolution speed increase as \(\mathcal{S}\) rises (Fig. 6d). The results indicate that as the government subsidies increase, the government tends toward pursuing the short-term incentive strategy. On the contrary, government subsidies have positive effect on enterprises’ participation strategy, and the more subsidies provided by the government, the less time it takes for enterprises to converge to long-term participation.

5.2.4 Effect of Training Cost on Evolution Results

Other parameters are: \(\alpha =0.6, \theta =0.4,\upkappa =0.6,\uprho =5, {{\mathcal{C}}_{E2}=20, \mathcal{C}}_{E1}=10, \fancyscript{r}=10, \mathcal{S}=15\). The initial probability is \({\fancyscript{z}}_{0}=0.5\, \mathrm{and }\, {\fancyscript{y}}_{0}=0.5\); training cost \(\fancyscript{d}\) paid by the government varies within the range [0.5, 3]; and the evolution result of the system is shown in Fig. 6e. Some cases in this situation converge slowly or fail to converge to a stable state. Therefore, to show the long-term trend, evolution time \(\fancyscript{t}\) is extended to [0, 50], and the evolution result of the system is again shown in Fig. 6e. The results indicate that if \(\fancyscript{d}\ge 2\), the government’s ESS converges to short-term incentive strategy; If \(0.5\le \fancyscript{d}\le 1.5\), there is less stability in whether the government chooses to pay the emergency management training cost for enterprises.

6 Conclusion and Future Prospects

With the complexity and impact of various emergencies worldwide continuing to increase, enterprise participation has become an indispensable part of effective response to emergencies. However, the performance of enterprises participating in emergency management needs to be further improved. Considering the challenges of enterprise participation and government incentives, this study constructed a two-stage evolutionary game model based on stakeholders’ bounded rationality to analyze the behavioral evolution characteristics of both participants in the emergency management system, and analyzed the system’s evolution path under different situations using SD simulation, thereby exploring the collaboration mechanism between the government and enterprises. We found that although enterprise participation in emergency management is affected by both influencing and decisive factors, their final decision depends on the utility function \(\mathcal{U}\left(\omega , \fancyscript{c}\right)\): if and only if \(\mathcal{U}\left(\omega , \fancyscript{c}\right)=\omega -\fancyscript{c}>0,\) an enterprise will choose the participation strategy and enter the emergency management system, initiating the second stage of the evolutionary game.

The simulation results reveal that in the second stage, there are two situations in which the government will choose long-term incentive strategy: the first is that although the enterprises adopt short-term participation strategy, the incremental benefit of enterprises supporting emergency management after training exceeds the training cost paid by the government; the second is that the enterprises adopt long-term participation strategy, and the incremental benefit of enterprise participation in emergency management exceeds the training cost and subsidies paid by the government. Correspondingly, there are also two situations in which the enterprises will choose long-term participation strategy: the first is that although the government adopt short-term incentive strategy, the sum of emergency management benefit and reputation benefit exceeds the incremental cost of long-term participation; the second is that the government adopt long-term incentive strategy, and the sum of incremental emergency management benefit, reputation benefit, and government subsidies exceeds the extra cost of pursuing long-term participation.

In addition, if other factors remain unchanged and the cost increment of long-term participation is low, the enterprises’ ESS converges to long-term participation, whereas as emergency management cost increases, enterprises tend to opt for short-term participation. With the increase of reputation benefit, enterprises will turn their ESS from short-term participation into long-term participation. In other words, reputation benefit has a positive impact on enterprises’ strategy choice. Similarly, government subsidies such as tax reduction and preferential policies incentivize enterprises to pursue a long-term participation strategy. If other factors remain unchanged, the increase in government subsidies will increase the evolution speed of enterprises’ ESS converging to long-term participation, but the ESS of the government simultaneously converges to short-term incentive. Finally, when the cost of emergency management training is low, there is less stability in whether the government chooses to pay the training cost for enterprises, but as the training cost rises, the ESS of the government quickly converges to short-term incentive.

Overall, if and only if the ESS of the system converges to {long-term participation, long-term incentive}, the benefit of CEM for both the government and enterprises outweigh the extra cost they paid. Therefore, the most important thing is that the government should adopt effective measures to promote the continuous participation of enterprises in emergency management. First, the government can provide continuous financial subsidies and promotion incentive for enterprises’ participation. Financial subsidies such as tax breaks can directly reduce the cost of enterprise participation, promotion incentive such as honor system can improve the reputation benefit of enterprise participation, and both financial subsidies and promotion incentive can promote continuous participation behavior of enterprises in emergency management. Second, the government also needs to optimize the communication mechanisms between itself and enterprises, and provide diversified participation channels and information support for enterprises. This can not only reduce the cost of coordination for both the government and enterprises in CEM, but also improve the benefit of CEM between the government and enterprises, so as to establish long-term collaborative relationships in emergency management. Third, the government should also provide systematic emergency training for enterprises to improve their capabilities to participate in emergency management, thereby giving full play to the advantages and potential of enterprise participation. For enterprises, since corporate social responsibility can positively and significantly influence sustainable competitive advantages (Wang et al. 2023), they should strengthen their emergency capabilities in daily operation and management from the perspective of corporate social responsibility, establish a good collaborative relationship with the government, and participate in the whole process of emergency management. In this way, the participation of enterprises can bring more benefit to themselves and the society.

Through two-stage evolutionary game modeling and simulation analysis of CEM between the government and enterprises, this study not only enriches the emergency management literature, but also provides a new theoretical perspective and methodological reference for future research on the multi-agent CEM mechanism. Meanwhile, the results provide important references for government measures promoting CEM performance through enterprise participation. However, this study also has some limitations that future research should address. First, while this study considers only enterprises and governments, CEM in practice also includes social organizations, citizens, media, and other stakeholders. Therefore, future research needs to comprehensively analyze collaboration relationship among multiple agents in the emergency management process. Second, as a complex system, the government-enterprise collaborative relationship in emergency management is affected by many factors that were given little attention in this study. Some influencing factors, such as relevant regulations and polices need to be further discussed in future research. In particular, the introduction of information and communication technology such as blockchain, 5G, and big data offers great potential to improve CEM capability with multi-agent participation. More studies are needed to further explore how the application of these technologies affects the game strategy choice of enterprises and governments for emergency management.

Change history

14 February 2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-024-00535-z

References

Ai, Y.F., and Q. Zhang. 2019. Optimization on cooperative government and enterprise supplies repertories for maritime emergency: A study case in China. Advances in Mechanical Engineering 11(5): Article 1687814019828576.

Ansell, C., A. Boin, and A. Keller. 2010. Managing transboundary crises: Identifying the building blocks of an effective response system. Journal of Contingencies & Crisis Management 18(4): 195–207.

Bennett, D. 2018. Emergency preparedness collaboration on Twitter. Journal of Emergency Management 16(3): 191–202.

Bosomworth, K., C. Owen, and S. Curnin. 2017. Addressing challenges for future strategic-level emergency management: Reframing, networking, and capacity-building. Disasters 41(2): 306–323.

Cao, X., and C.Y. Li. 2020. Evolutionary game simulation of knowledge transfer in industry-university-research cooperative network under different network scales. Scientific Reports 10(1): Article 4027.

Chen, Y.X., J. Zhang, P.R. Tadikamalla, and X.T. Gao. 2019a. The relationship among government, enterprise, and public in environmental governance from the perspective of multi-player evolutionary game. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16(18): Article 3351.

Chen, Y.X., J. Zhang, P.R. Tadikamalla, and L. Zhou. 2019b. The mechanism of social organization participation in natural hazards emergency relief: A case study based on the social network analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16(21): Article 4110.

Diehlmann, F., M. Lüettenberg, L. Verdonck, M. Wiens, A. Zienau, and F. Schultmann. 2021. Public-private collaborations in emergency logistics: A framework based on logistical and game-theoretical concepts. Safety Science 141: Article 105301.

Du, L.Y., and L. Qian. 2016. The government’s mobilization strategy following a disaster in the Chinese text: An evolutionary game theory analysis. Natural Hazards 80(3): 1411–1424.

Fan, B., Z.P. Li, and K.C. Desouza. 2022. Interagency collaboration within the city emergency management network: A case study of super ministry reform in China. Disasters 46(2): 371–400.

Fan, R.G., Y.B. Wang, and J.C. Lin. 2021. Study on multi-agent evolutionary game of emergency management of public health emergencies based on dynamic rewards and punishments. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18(16): Article 8278.

Friedman, D. 1998. On economic applications of evolutionary game theory. Journal of Evolutionary Economics 8: 15–43.

Gao, H.W., L. Petrosyan, H. Qiao, and A. Sedakov. 2017. Cooperation in two-stage games on undirected networks. Journal of Systems Science & Complexity 30(3): 680–693.

Gupta, S., S. Modgil, A. Kumar, U. Sivarajah, and Z. Irani. 2022. Artificial intelligence and cloud-based collaborative platforms for managing disaster, extreme weather and emergency operations. International Journal of Production Economics 254: Article 108642.

Hamann, R., L. Makaula, G. Ziervogel, C. Shearing, and A. Zhang. 2020. Strategic responses to grand challenges: Why and how corporations build community resilience. Journal of Business Ethics 161(4): 835–853.

Hart, P. 2013. After Fukushima: Reflections on risk and institutional learning in an era of mega-crises. Public Administration 91(1): 101–113.

Johnson, B.R., E. Connolly, and T.S. Carter. 2011. Corporate social responsibility: The role of fortune 100 companies in domestic and international natural disasters. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 18(6): 352–369.

Kapucu, N., T. Arslan, and F. Demiroz. 2010. Collaborative emergency management and national emergency management network. Disaster Prevention and Management 19(4): 452–468.

Kong, F., and S. Sun. 2021. Understanding the government responsibility and role of enterprises’ participation in disaster management in China. Sustainability 13(4): Article 1708.

Levine, D.K., and W. Pesendorfer. 2007. The evolution of cooperation through imitation. Games and Economic Behavior 58(2): 293–315.

Li, H.Y. 2017. Evolutionary game analysis of emergency management of the middle route of South-to-North water diversion project. Water Resources Management 31(9): 2777–2789.

Li, S., F. Xu, and Q.F. Yang. 2021. Research on the influence mechanism of personal initiative on enterprise emergency management ability. Frontiers in Psychology 12: Article 618034.

Li, C.D., F.S. Zhang, C.J. Cao, L. Yang, and T. Qu. 2019. Organizational coordination in sustainable humanitarian supply chain: An evolutionary game approach. Journal of Cleaner Production 219: 291–303.

Li, H.Y., X.L. Zhang, U. Khaliq, and F.U. Rehman. 2023. Emergency engineering reconstruction mode based on the perspective of professional donations. Frontiers in Psychology 14: Article 971552.

Linnenluecke, M.K., and B. McKnight. 2017. Community resilience to natural disasters: The role of disaster entrepreneurship. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy 11(1): 166–185.

Liu, J.D., C.Q. Dong, S. An, and Y.A. Guo. 2021. Research on the natural hazard emergency cooperation behavior between governments and social organizations based on the hybrid mechanism of incentive and linkage in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18(24): Article 13064.

Liu, D.H., X.Z. Xiao, H.Y. Li, and W.G. Wang. 2015. Historical evolution and benefit-cost explanation of periodical fluctuation in coal mine safety supervision: An evolutionary game analysis framework. European Journal of Operational Research 243(3): 974–984.

Lu, B.J., and L.L. Zhu. 2022. Public health events emergency management supervision strategy considering citizens’ and new media’s different ways of participation. Soft Computing 26(21): 11749–11769.

Lu, R.W., X.H. Wang, Y. Hao, and D. Li. 2018. Multiparty evolutionary game model in coal mine safety management and its application. Complexity 2018: Article 9620142.

Luiza, I., L.H. Matsunaga, C.C. Machado, H. Gunther, D. Hillesheim, C.E. Pimentel, J.C. Vargas, and E. D’Orsi. 2020. Psychological determinants of walking in a Brazilian sample: An application of the theory of planned behavior. Transportation Research Part F—Traffic Psychology and Behaviour 73: 391–398.

Luo, Y.M., Y.K. Zhang, and L. Yang. 2022. How to promote logistics enterprises to participate in reverse emergency logistics: A tripartite evolutionary game analysis. Sustainability 14(19): Article 12132.

Lüttenberg, M., A. Schwärzel, M. Klein, F. Diehlmann, M. Wiens, and F. Schultmann. 2022. The attitude of the population towards company engagement in public-private emergency collaborations and its risk perception: A survey. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 82: Article 103370.

Lv, X. 2017. Managing uncertainty in crisis: Exploring the impact of institutionalization on organizational sense-making. Berlin: Springer.

Nan, R., J. Wang, and W. Zhu. 2022. Market participation in vital emergent events management: Generative logic, risk spillover and counter-risk choices. Contemporary Finance & Economics 2: 28–40 (in Chinese).

Oh, N., A. Okada, and L. Comfort. 2014. Building collaborative emergency management systems in Northeast Asia: A comparative analysis of the roles of international agencies. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice 16(1): 94–111.

Olszewski, C., and L. Siebeneck. 2021. Emergency management collaboration: A review and new collaboration cycle. Journal of Emergency Management 19(1): 57–68.

Petrosyan, L.A., A.A. Sedakov, and A.O. Bochkarev. 2016. Two-stage network games. Automation and Remote Control 77(10): 1855–1866.

Puliga, G., and L. Ponta. 2021. COVID-19 firm’s fast innovation reaction analyzed through dynamic capabilities. R & D Management 52(2): 331–342.

Semasinghe, P., E. Hossain, and K. Zhu. 2015. An evolutionary game for distributed resource allocation in self-organizing small cells. IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing 14(2): 274–287.

Shah, A.A., J.Z. Ye, L. Pan, R. Ullah, S.I.A. Shah, S. Fahad, and S. Naz. 2018. Schools’ flood emergency preparedness in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province, Pakistan. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 9(2): 181–194.

Shao, Z., M. Li, C. Han, L. Meng, and Q. Wu. 2022. Simulation and cooperation mechanism of construction waste disposal based on evolutionary game. Chinese Journal of Management Science. https://doi.org/10.16381/j.cnki.issn1003-207x.2021.1728 (in Chinese).

Shi, P.J. 2012. On the role of government in integrated disaster risk governance—Based on practices in China. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 3(3): 139–146.

Shi, P.Z., Y. Hao, C.L. Sun, and L.J. Zhang. 2023. Evolutionary game and simulation analysis on management synergy in China’s coal emergency coordination. Frontiers in Environmental Science 11: Article 1062770.

Sun, Q.Q., H. Chen, R.Y. Long, and J.H. Yang. 2023. Who will pay for the “bicycle cemetery”? Evolutionary game analysis of recycling abandoned shared bicycles under dynamic reward and punishment. European Journal of Operational Research 305(2): 917–929.

Tang, Y., K.R. Hong, Y.C. Zou, and Y.W. Zhang. 2021. Equilibrium resolution mechanism for multidimensional conflicts in farmland expropriation based on a multistage Van Damme’s model. Mathematics 9: Article 1208.

Tau, M., D. Van Niekerk, and P. Becker. 2017. An institutional model for collaborative disaster risk management in the Southern African Development Community (SADC) region. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 7(4): 343–352.

Wang, Y.Q., and H. Chen. 2022. Blockchain: A potential technology to improve the performance of collaborative emergency management with multi-agent participation. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 72: Article 102867.

Wang, G., Y.C. Chao, Y. Cao, T.L. Jiang, W. Han, and Z.S. Chen. 2022. A comprehensive review of research works based on evolutionary game theory for sustainable energy development. Energy Reports 8: 114–136.

Wang, X.T., M. Hussain, S.F. Rasool, and H. Mohelska. 2023. Impact of corporate social responsibility on sustainable competitive advantages: The mediating role of corporate reputation. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-28192-7.

Wang, X.H., Y.F. Wu, L. Liang, and Z.M. Huang. 2014. Service outsourcing and disaster response methods in a relief supply chain. Annals of Operations Research 240(2): 471–487.

Wang, L., C.Y. Xia, and J. Wang. 2013. Coevolution of network structure and cooperation in the public goods game. Physica Scripta 87(5): Article 055001.

Wei, S.K., H. Yang, J.X. Song, K.C. Abbaspour, and Z.X. Xu. 2012. System dynamics simulation model for assessing socio-economic impacts of different levels of environmental flow allocation in the Weihe River Basin, China. European Journal of Operational Research 221: 248–262.

Xie, K.F., S.F. Zhu, and P. Gui. 2022. A game-theoretic approach for CSR emergency medical supply chain during COVID-19 crisis. Sustainability 14(3): Article 1315.

Xiong, L., and R.D. Xue. 2023. Evolutionary game analysis of collaborative transportation of emergency materials based on blockchain. International Journal of Logistics-Research and Application. https://doi.org/10.1080/13675567.2023.2173160.

Yang, A.H., and W. Zhang. 2018. Company orientation and community orientation: Understanding two different modes of enterprise in disaster governance. Journal of Risk, Disaster & Crisis Research 2: 167–192 (in Chinese).

Zhang, L. 2021. Research on emergency management guarantee for enterprises to participate in major public emergencies. Journal of Inner Mongolia University of Finance and Economics 19(6): 120–123 (in Chinese).

Zhang, M., and Z.J. Kong. 2022. A tripartite evolutionary game model of emergency supplies joint reserve among the government, enterprise and society. Computers & Industrial Engineering 169: Article 108132.

Zhang, H.B., and X. Tong. 2015. Changes in the structure of emergency management in China and a theoretical generalization. Social Science in China 3(58–84): 206 (in Chinese).

Funding

This work was supported by the Major Project of National Social Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 21&ZD166), the National Social Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 22VRC200), and the China Scholarship Council (CSC, Grant No. 202206420064).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The original version of this article has been revised: Figure 1 has been corrected.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Chen, H. & Gu, X. A Two-Stage Evolutionary Game Model for Collaborative Emergency Management Between Local Governments and Enterprises. Int J Disaster Risk Sci 14, 1029–1043 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-023-00531-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-023-00531-9