Abstract

In this paper, we analyse a sample of voluntarily published country-by-country reports (CbCRs) of 35 multinational enterprises (MNEs). We assess the value added and the limitations of qualitative and quantitative information provided in the reports based on a comparison to individual MNEs’ annual financial reports and aggregate CbCR data provided by the OECD. In terms of data quality, we find that the inclusion of intra-company dividends and equity-accounted profits are a minor concern on average but that for individual MNEs corrections might be substantial. Our sample MNEs seem to pay higher effective tax rates than the global average and many of them report relatively little profit in tax havens. We only find a very weak correlation of the location of profits and effective tax rates. This might indicate that more tax transparent MNEs avoid taxes less aggressively. However, our assessment of different tax risk indicators reveals important variations between companies.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The introduction of country-by-country reporting (CbCR) can be regarded as a major breakthrough for the internationally coordinated efforts to curb corporate tax base erosion and profit shifting. Country-by-Country Reports (CbCRs), prepared according to the minimum standards of OECD BEPS Action 13, provide a global picture of multinational enterprises’ (MNEs) tax payments, profits, and economic activities in each country where they operate and should allow tax administrations to better identify potential tax avoidance risks. The OECD has made aggregated country-by-country data available to the wider public, allowing researchers to refine global estimates of profit shifting (García-Bernardo & Janský, 2021) or evaluate the impacts of policy reforms such as the global corporate minimum tax (Barake et al., 2021). Data confidentiality has thus far limited more detailed analyses based on firm-level data including, e.g., Fuest et al. (2022a), Fuest et al. (2022b), and Bratta et al. (2021). The European Union has decided to make EU-wide public CbCR mandatory starting from the first financial year after 22 June 2024 (EU, 2021). Until then, most company-level CbCRs will remain confidential. However, an increasing number of MNEs voluntarily publish CbCRs and thereby provide more fiscal transparency.

In this paper, we analyse a sample of voluntarily published CbCRs of 35 MNEs along the following lines: First, what is the value added of CbCR and, more specifically, of these public micro CbCRs for the analysis of corporate tax avoidance, and what are the potential limitations? Second, what can these CbCRs tell us about individual MNEs’ tax aggressiveness, and can we observe general differences between MNEs voluntarily publishing CbCRs and the world average with regard to effective tax rates, use of tax havens and other tax risk indicators?

There is evidence from other voluntary disclosures—e.g., Kays (2022), Breuer et al. (2022) and Flagmeier et al. (2023), as discussed in the context of the CbCR voluntary publication by Hackett and Janský (2022)—that firms indeed act strategically with regard to voluntary disclosure. We might thus expect public CbCR to differ from confidential CbCRs for at least two reasons: First, MNEs face reputational risks when they are perceived as tax dodgers which might even involve negative stock market reactions (Müller et al., 2021; Rusina, 2020). We might thus expect that MNEs publishing their CbCR fear “name and shame” less than others either because they have nothing to hide or because they hide it too well to be discovered. Indeed, Adams et al. (2022), suggest that less tax-aggressive firms are more transparent about their tax activities. Second, public CbCRs address a bigger and potentially less informed audience than confidential CbCRs which mainly address tax auditors. This might favour a more careful reporting as the general public might more easily misinterpret inflated profits that arise due to double-counting of profits, for example.

We compare the voluntarily published reports to information obtained from MNEs’ consolidated financial accounts and to aggregate CbCR data provided by the OECD to highlight the general benefits of CbCR but also discuss some of their commonly understood limitations (e.g., a known data limitation includes the double-counting of dividends which is considered to be an issue in aggregate CbCR but less so in our sample of voluntarily published reports). We also assess to what extent profits of associates and joint ventures might bias tax risk indicators based on CbCR profits—another potential issue flagged by the OECD (2017)—and identify a few individual companies which explicitly correct for this. We explore the reasons individual MNEs provide for low effective tax rates (ETRs) and find they explain the frequently observed gap between financial profits and the actual tax base to a limited but non-systematic extent.

The additional qualitative information included in many voluntarily published CbCRs helps us to better understand MNEs’ use of tax havens and to assess a potential correlation between their global ETRs and their tax haven use. We provide an overview of high-risk activities our sample MNEs perform in tax havens and non-havens and compute additional tax risk indicators such as the share of profits reported in tax havens and the misalignment of profits and economic activity which may be partly explained by profit shifting activities.

We conclude that concerns raised with respect to data quality and interpretation are valid and that some degree of uncertainty remains attached to tax risk indicators based on CbCR data. Illustrating the sensitivity of results to data corrections, whenever possible, suggests that the adjustments are gradual and do not undermine the general qualitative conclusions drawn from the data. However, a few percentage points higher or lower ETRs might make a difference for individual companies. Some MNEs appear to be aware of this and correct their reports accordingly. This might contribute to establishing best practices and increasing data quality in the future.

Early publishers of CbCR seem to pay higher taxes than the global average and the sample majority reports a lower share of profits in tax havens. For the sample as a whole, we find a weak correlation of the location of profits and ETRs, which would be consistent with some tax-induced profit shifting. This correlation is not robust and relatively small compared to studies based on confidential CbCR. However, there is some heterogeneity in the sample: While the majority of sample MNEs score low on most tax risk indicators, five companies stand out in terms of identified tax risks.

In the tax avoidance literature, the use of data from confidential tax returns has emerged as the best practice on the research frontier, but these have been available—and used—only in particular countries, such as the USA (Dowd et al., 2017), the UK (Bilicka, 2019), South Africa (Reynolds & Wier, 2019), and Uganda (Koivisto et al., 2021). Researchers interested in better country coverage and international comparisons have exploited other resources, such as the private databases Orbis (Egger et al., 2009; Fuest & Riedel, 2012) and Compustat (Dyreng et al., 2017; Markle & Shackelford, 2012), official foreign direct investment statistics (Bolwijn et al., 2018; Janský & Palanský, 2019), and foreign affiliate statistics (Tørsløv et al., 2022). Despite increased research interest in recent years, no single data source has emerged as a clear solution to the enduring trade-off between the quality of confidential tax returns data and the need for comprehensive country coverage (Janský, 2023). Some of the most promising candidates for addressing this trade-off have been, and likely still are, the various types of CbCR data, which have become available in recent years and have been hailed as a potential panacea due to their expected positive impact on corporate behaviour, financial markets and development (Wójcik, 2015).

While the private CbCR standard studied in this paper covers the widest range of MNEs, previously implemented mandatory public CbCR standards only focused on specific industries. The longest-lasting one for the extractive industries may have had an effect (Johannesen & Larsen, 2016), but the data itself has not proven to be very useful (Stausholm et al., 2022). By comparison, a greater body of literature has focused on CbCRs in the financial industry. Banks and other financial institutions have been required to publish CbCRs since 2016 as part of the Capital Requirements Directive IV, and a number of papers have observed the effects of this new regulation (Dutt et al., 2019a, 2019b; Hugger, 2019; Joshi et al., 2020; Tuinsma et al., 2023) while an increasing number of papers have made use of the data to analyse taxation (Dutt et al. 2019b; Barake, 2022; Bouvatier et al., 2017; Brown et al., 2019; Fatica & Gregori, 2020; Janský, 2020). A growing body of literature studies the relationship of voluntary disclosure of tax information and tax behaviour (Müller et al., 2020) as tax information is becoming more important for the assessment of companies’ corporate social responsibility (CRS). For example, the Global Reporting Initiative has included country-by-country tax reporting into their CRS reporting standard in 2019 (Global Reporting Initiative, 2020). In extending the range of types of CbCR data studied, we contribute to the broader literature studying the informative value of various kinds of tax-related disclosure.

In this paper, we pioneer the use of one specific type of CbCR data—prepared according to the OECD BEPS Action 13’s minimum standards and voluntarily published by MNEs. We contribute to the literature by assessing the magnitude of frequently mentioned data limitations of early CbCR data and by analysing indicators of tax aggressiveness at the company level. Micro CbCR based on the OECD BEPS standard is likely to become a key data source in future tax avoidance research and we hope to contribute to the understanding of its value added and potential challenges for research.

The paper is structured as follows: Sect. 2 introduces the data and sample selection. Section 3 discusses the benefits and limitations of CbCR data and assesses the potential bias introduced by double-counting of profits and the inclusion of associate and joint venture profits. Section 4 analyses our sample based on different tax risk indicators. These include MNEs’ high-risk functions and their share of profits located in tax-havens, their global ETRs and an analysis of the tax-sensitivity of profits with regard to tax rate indicators.

2 Data

As part of the OECD’s Anti-BEPS Action 13, governments have started to collect CbCRs from large MNEs. In those CbCRs, the MNEs must report profits, tax payments and economic activity for each tax jurisdiction in which they operate. Data from these reports have recently been made publicly available but only in aggregated form by the OECD for the years 2016, 2017 and 2018. A growing number of companies decides to voluntarily publish their individual CbCRs, and we analyse these in this paper.

For our analysis, we use the public country-by-country reports dataset of the EU Tax Observatory (Aliprandi et al., 2022), matched consolidated profits from financial accounts collected by Aliprandi and von Zedlitz (2023), and individual CbCR and financial reports of our sample MNEs to extract the profits of equity-accounted joint ventures and associates, business activities and other qualitative information.

The Public Country-by-Country Reports Dataset comprises 103 groups for the years 2017–2020 but only 46 with complete information on our variables of interest. We drop one group and one group-year because of suspected reporting errors.Footnote 1 We further limit our sample to groups with a turnover of EUR 750 million, the threshold at which they would legally be required to file confidential CbCR to tax authorities. This should ensure a minimum level of consistency when comparing our sample to the aggregate CbCR statistics published by the OECD (2022). In addition, our final sample only comprises groups which provide a sufficiently detailed disaggregation of profits by country. The reason is that some groups report part of their profits aggregated by country groups (e. g. “other Americas”). We exclude groups when the share of not properly disaggregated profits amount to more than 5% of a group’s total profits.

We obtain a final sample of 35 MNEs, which collectively report activity in 147 jurisdictions. Most of the sample MNEs are headquartered in Europe, five in Australia and one respectively in the USA and India. In terms of industry classification, the most important industries in the sample are manufacturing (9 groups), mining and quarrying (8 groups), followed by transportation and storage (4 groups) and information and communication (4 groups) (see Appendix Table 7 for a full list of sample MNEs with headquarter jurisdictions, industries and available years).

Our variables of interest include profit/loss before income tax, income tax accrued in the current year, number of employees, tangible assets, and unrelated party revenues. Table 1 provides summary statistics for our sample.

The largest company in terms of total employee numbers is Telefonica with approximately 117,000 employees reported worldwide in 2019, followed by Vodafone with 101,000, and Wesfarmers with 87,000. Erg is the smallest MNE in the sample with 778 employees. Shell and Rio Tinto report by far the highest worldwide sums of profits, and Enav the lowest positive profit, with Shell’s sum of global profits in 2018 being approximately 360 times higher than Enav’s in 2020.

The distribution of profits across countries reflects the heterogeneity of the MNEs in our sample. While Shell reports significant profits in many different countries, some MNEs such as Iberdrola and Rio Tinto concentrate profits in their headquarter jurisdictions. Anglo American’s profits are highly concentrated in Australia, and Telefonica’s in Brazil.

We note that Vodafone, which was the first MNE to publish its CbCR voluntarily, also publishes supplementary country-by-country data alongside the CbCR because it considers the OECD minimum standards unsuitable for its objectives (Faccio & FitzGerald, 2018).Footnote 2 To ensure consistency, we do not include this supplementary data from Vodafone in our analysis.

2.1 Samples

As we compare the CbCRs to consolidated accounts, we use all available observations from the CbCRs in Sect. 3. In Sect. 4, we adapt the sample to be more suitable for an analysis of tax risk indicators: As we expect only profitable companies to pay taxes, we keep only profit-making sub-groups. We average observations across all available years to reduce the general volatility of profits and revenues over time and to avoid attributing more weight to groups for which several years are available. Table 2 presents summary statistics for each step of the sample selection. For the computations of ETRs, we set negative tax payments to zero.Footnote 3

3 Lessons from comparing public micro CbCRs to other data sources

For research on the taxation of MNEs, CbCR data constitutes the most promising candidate to address the trade-off between the quality of confidential tax returns and the need for comprehensive country coverage (Janský, 2023). Aggregate CbCR data has been used in recent profit shifting research (García-Bernardo & Janský, 2021) while confidential, country-specific company-level data has been used for Germany (Fuest et al., 2022a) and Italy (Bratta et al., 2021). Still, research based on CbCRs faces several challenges, which include the small number of years for which CbCR data is currently available, confidentiality of company-level CbCR and quality issues discussed in detail in the OECD’s disclaimer regarding the limitations of the country-by-country report statistics (OECD, 2021).

In the following sections, we present insight gained from the analysis of a sample of voluntarily published CbCRs with respect to data quality and potential best practices on the way to greater tax transparency. Combining CbCRs with information from consolidated financial reports can shed light on the frequently raised issues of double-counting of dividends in CbCR data and the potential bias of ETRs caused by the inclusion of equity-accounted associates and joint ventures. In contrast to what disclaimers for aggregate CbCR suggest, most sample MNEs exclude intra-company dividends. Some MNEs correct for equity-accounted participation results, most notably those with high shares of equity-accounted profits in total profits. The qualitative information some MNEs include in their CbCRs to explain low ETRs may improve the public’s understanding of where MNEs pay taxes and why. Important limitations remain but some are likely to become less problematic as the reporting standard evolves and longer time series become available.

3.1 Double-counting of profits

Profits in CbCR data may be inflated by the inclusion of intracompany dividends leading to double-counting as the earlier OECD guidance on CbCR reporting did not specify the treatment of intra-company dividends for the reporting of pre-tax profits. As a result, some MNEs include intra-group dividends both in the country of origin (as profit) and in the receiving country (as dividends). This occurs, for example, when dividends received from a subsidiary are counted as profits of the subsidiary but also added to the parent’s pre-tax profits. This biases ETRs as the tax payments related to this income are counted only once, i.e. in the subsidiary’s country of tax residence, while the dividends received by the parent are usually at least partly tax-exempt in the parent’s country of tax residence.

Italy, the Netherlands, Sweden, and the UK have issued CbCR country notes quantifying the estimated bias in aggregate CbCR profits due to the double-counting of dividends. Estimates at the macro scale also exist for the US CbCR data provided by the BEA (García-Bernardo et al., 2022; Horst & Curatolo, 2020).

Based on the comparison of CbCRs and tax returns, the Netherlands suggest that double-counting of dividends amounts to approximately EUR 5.8 billion or 16% of total profits for the Dutch CbCR positive-profit sample. Italy finds that, on average, the share of received dividends amounts to 38% (median 28%) of Italian MNEs’ reported profits (positive-profit sample). For the UK, the HMRC estimates that “approximately 25% of UK headquartered groups had included dividends in CbCR” (OECD, n.d.(c)) and that intragroup dividends receivable included in profits amounted to GBP 55 billion or 49% of domestic CbCR profit reported by UK MNEs. Sweden’s country note suggests that in 2017 tax-free dividends included in corporate income tax returns amounted to SEK 266 billion. If all Swedish MNEs included dividends in CbCR profits, total profits of SEK 512 billion should be reduced by SEK 266 billion (52%) (Table 3).

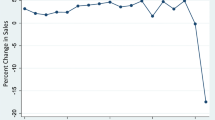

Many early publishers of CbCRs explicitly state that they exclude intra-company dividends when compiling CbCR (e.g. Anglo American 2019a, ENI 2019a, Repsol 2019a, Rio Tinto 2019a, Shell 2019a). This can also be confirmed by comparing aggregate CbCR profits to consolidated financial accounts (Aliprandi & von Zedlitz, 2023). If the sum of CbCR profits exceeds consolidated global profit, this might indicate the inclusion of intra-company dividends. In our sample, the sum of CbCR profits is higher than consolidated profits only in few cases. As can be seen in Fig. 1, plotting the distribution of the ratio between CbCR and consolidated profits the majority of observations lie between 0.9 and 1.1. From Table 4 it can be seen that the median of the sample is 1, while the average is 0.4. The average is driven by two large outliers related to Vodafone that reports large losses. We assume that the CbCR profits of seven companies (Atlantia, Orica, Evraz, Piaggio, Buzzi Unicem, Snam and Sol) include relevant intra-company dividends because their CbCR profits are significantly inflated compared to consolidated profits. We thus suggest a correction of their global CbCR profits in Sect. 4.2.

Ratio of CbCR and consolidated profit: sample distribution. The figures plot the distribution of the ratio between CbCR profit and consolidated profit. Large negative values are due to large losses reported by Vodafone, while large positive values consist of companies including intracompany dividends. Subfigure a plots the entire sample, while subfigure b zooms in between Q10 and Q90

The relatively low occurrence of double-counted profits in our sample contrasts with the comparably important magnitude of the phenomenon in aggregate CbCR data. Estimates of the latter refer mostly to headquarter profits only and might thus also look less important in relation to MNEs’ global consolidated profits. However, some double-counting of profits might also occur in the case of foreign affiliates. For example ENI, which explicitly excludes intra-company dividends from its CbCR, highlights that the inclusion of dividends would mostly affect the headquarter jurisdiction Italy but also the Netherlands and the UK.

3.2 Profits of equity-accounted associates and joint ventures

In financial accounting, the net profits of joint ventures and associates may be included in total profits on an accrual basis. As CbCR is based on financial profits, this gives rise to a conceptual challenge: MNEs are allowed to include the participation results from associates and joint ventures in CbCR profits—if accounted based on the equity method. What is problematic is that in line with financial reporting, taxes paid by the associate or joint venture, its employees or other economic variables, are not included in CbCRs. As a result, the inclusion of associates and joint ventures affects reported profits but not the remaining CbCR variables. This is a potential source of bias when calculating ETRs or other tax risk indicators, as has been pointed out by the OECD (2017). The Netherlands’ notes on country-specific analysis, for example, estimate that aggregate positive CbCR profits reported in the Netherlands are biased upwards by 27% “due to shares of result in associates and joint ventures, differences in accounting standards between the two reports, one-off (de)mergers, takeovers, or disposals” (OECD, n.d.(a)).

In our sample, the bias caused by the inclusion of participation results potentially affects 28 out of 35 groups. The remaining seven groups explicitly exclude income from joint ventures and associates from their CbCR profits (Aegon, Enel, Repsol, Rio Tinto, and South32) or do not even include equity-accounted profits in “profit before taxes” (Cipla and Enav). By combining individual MNEs’ CbCRs and consolidated financial accounts we assess the potential magnitude of this bias for our sample. Most groups provide net income from associates and joint ventures in their consolidated income statementFootnote 4 which on average accounts for approximately 13% of the sample’s total consolidated profits. 20 MNEs have equity-accounted profits below 10%, 10 even below 1%. The groups that do not correct their CbCR profits for received equity-accounted incomes have a lower average share of equity-accounted profits in total (9%), while those that adjust their CbCR profits have a higher one on average (38%) (Fig. 2). This suggests that high equity-accounted profits might be an incentive to report better in order to prevent misinterpretations resulting from strongly biased profits.Footnote 5

Profit of equity-accounted associates and joint ventures. The figure plots profits of equity-accounted associates and joint ventures in % of consolidated profit for the 10 largest groups in the sample and two sample means. Bars with reduced fill intensity indicate groups that do not include the equity-accounted profits in their CbCR profits (N = 5). “Mean includers” is the sample mean of groups whose CbCR profits are likely to include equity-accounted profits (N = 25). Cipla and Enav report even consolidated profit before tax without equity-accounted profit and are thus excluded. For three groups, information is missing. The numbers represent means over available years

While the annual reports include a list of associates and joint ventures, in most cases with addresses, a breakdown of net income by entity and thus country is not always available or includes only the most important joint ventures and associates. As a result, we can only correct profits by country in an exemplary and non-systematic manner.

For example, Anglo American (2019b), Buzzi Unicem (2020), ENI (2019b), and Vodafone (2020) provide a breakdown for the most important joint ventures and associates. Our analysis suggests that, even if moderate at the aggregate level, joint venture profits may distort individual countries’ risk indicators, especially if little economic activity is carried out in the country. For example, ENI’s 2017 profit in Spain, where it has less than 100 employees, would increase more than tenfold (from USD 5 to 76 million) if losses from its joint venture Unión Fenosa Gas SA were excluded from its CbCR profits. However, in Italy, where ENI has more than 20,000 employees, net income from joint ventures and associates would bias profits only by 0.1–28%. Similarly, AngloAmerican’s losses in Colombia, where it reports only 1.5 employees would look much bigger after subtracting the positive equity-accounted income from Cerrejón. In contrast, in Australia, Brazil, and South Africa a tentative correction for equity-accounted net income would change profit by much less (0.3–37%). Buzzi Unicem is the only MNE with a break-down of equity-accounted profits by entity for which we identify an associate located in a tax havenFootnote 6 but these profits amount to less than 0.3% of profits reported there.

Our analysis at sub-group level thus indicates that individual sub-group ETRs or other measures based on individual sub-group profits should be interpreted with caution as net income from equity-accounted entities might bias them both upwards or downwards, especially in branches with little economic activity. This, however, does not seem to hold for profits in tax havens as no company reports relevant associate or joint venture income in tax havens.

We conclude that profits of equity-accounted associates and joint ventures may thus be a source of bias in our analysis of company-level tax risk indicators. As most MNEs report positive profits from equity-accounted investments, their global ETRs likely need to be corrected upwards. Also, the share of profits reported in tax havens would need to be corrected upwards if we exclude these profits from our analysis, as our sample MNEs do not report relevant equity-accounted income in tax haven sub-groups.

3.3 Differences between financial profits and the tax base

The voluntarily published CbCRs are mostly sourced from and thus broadly consistent with consolidated financial accounts. Effective tax rates calculated based on CbCRs thus facilitate the assessment of corporate tax payments in relation to financial profits in each country. However, these financial profits are not necessarily consistent with taxable profits due to differences in financial and tax accounting (Hanlon & Maydew, 2009). These include timing differences due to different depreciation rules and permanent differences, e.g. when certain payments are regarded as deductible expense for financial accounting but not for tax purposes. In this regard, ETRs based on CbCR data suffer from similar shortcomings as ETRs based on financial accounts.

As MNEs are not required to publish their tax accounting along with financial accounts, the reasons for observed discrepancies between ETRs and statutory tax rates also remain somewhat opaque in CbCR data. Loss carryover—likely an important share of observed discrepancies—will be easier to control as longer time series become available. However, the effects of other features of the tax system, such as depreciation schemes and tax incentives, cannot be analysed systematically using publicly available data.

Based on data from MNEs’ tax filings, the Netherlands’ notes on CbCR data (OECD, n.d.(a)) provide rough estimates of how much the distinctive features of the tax system contribute to the observed gap between MNEs’ financial and taxable profits. Having corrected CbCR profits for the double-counting of dividends, the authors suggest subtracting an additional 19% for loss carry-overs, and another 9% to make CbCR profits better comparable to taxable profits. The components of this correction include estimated commercial-fiscal differences and adding interest and costs that would not be deductible for tax purposes. The authors also subtract part of the profit that benefits from intellectual property (IP) tax incentives, which illustrates an important controversy regarding the interpretation of ETRs. While a share of IP profits is exempt from the CIT base under the Dutch tax system, this is not so in other countries. For inter-country comparisons of ETRs, it is thus not ideal to use taxable profits as the denominator as they are defined in a non-consistent way across jurisdictions.

Some of our sample MNEs also provide information that is additional and complementary to what is available in the OECD standard. Notably, some MNEs explain why they pay relatively low ETRs in certain jurisdictions.Footnote 7 For example, Vodafone (2018) explains in detail the availability of historic losses in Luxembourg which allows a large amount of income received to be offset so that no corporation tax is recorded in Luxembourg. The availability of historic losses does not form part of the data required by the OECD standard but is provided voluntarily to improve the readers’ understanding. Vodafone also indicates that it pays “little or no UK corporation tax” because of a capital allowance and debt interest relief. Similarly, Rio Tinto (2019a) explains how its entities in Belgium qualify for the Diamond Tax Regime, which results in an effective tax rate lower than the general statutory corporate tax rate in Belgium. Repsol (2019a) even computes ETRs for each jurisdiction and provides explanations for differences to the statutory rates including tax deductions in Spain, the use of an accelerated amortization tax regime in Peru, losses from the previous year in Mexico, tax credits generated by losses from previous years in Luxembourg, or non-deductible losses in Bolivia and the Netherlands which explain why the ETR is higher than the statutory rate.

This information can help explain why ETRs may differ from statutory rates but is, in most cases, not detailed enough to quantitatively adjust the ETRs or to help clarify how much of the gap between an ETR and the statutory rate can be explained by a certain tax incentive. The bias due to loss carryovers can be reduced by averaging CbCR data over several years as more data becomes available. When it comes to tax incentives, it depends on the research question whether or not they should be considered a potential source of bias of ETRs. Even if a tax incentive increases the gap between financial and taxable profits, it results in lower tax payments. This may be captured correctly by ETRs computed based on financial profits but not by ETRs based on taxable profits. In addition, individual features of the tax code such as loss carryover, certain depreciation schemes, and tax incentives can also be used strategically by MNEs and form part of global tax optimisation schemes.

4 Tax risk indicators

In our analysis of voluntarily reported CbCR data, we analyse standard tax risk indicators: the MNEs’ activities and profits booked in tax havens, effective tax rates, and the misalignment of profits with reported economic activity. We discuss potential biases introduced to our results by the above described shortcomings of CbCR data and illustrate the effect of corrections where possible. Information from financial accounts allows us to correct profits for double-reporting and participation results as discussed in Sects. 3.1. and 3.2. For the calculation of tax risk indicators, we keep only profitable sub-groups as we would not expect loss-making companies to pay tax and as we are mainly interested in the distribution of positive profits across countries.

4.1 MNEs’ presence in tax havens

Different channels are used by MNEs for aggressive tax planning. Ramboll and Corit (2015) and Spengel et al. (2016) group them into three channels: aggressive tax planning via interest payments, via royalty payments, and via strategic transfer pricing (e.g. intra-group sale of goods or provision of services). CbCRs facilitate a global view of where each MNE locates some of the functions, risks and assets that can be linked to aggressive tax planning. High-risk functions performed in tax havens include intra-group finance, IP licensing, marketing hubs, provision of insurance or headquarter services, and holding functions, each of which is discussed in more detail below.

Tax rules typically allow a deduction for interest paid or payable in arriving at the tax measure of profit. The higher the level of debt in a company, and thus the amount of interest it pays, the lower its taxable profit. Intra-group lending arrangements can result in tax avoidance if the interest payment is structured in a way that allows the interest to be received in a jurisdiction that either does not tax the interest income, or which subjects such interest to a lower tax rate than the jurisdiction from which the payment is made.

MNEs can strategically place their profitable IP rights in low-tax locations to reduce overall tax rates. IP owned in low-tax jurisdictions is licensed to an entity in high tax jurisdiction in return for a royalty payment. Tax rules typically allow a deduction for royalty paid or payable in arriving at the tax measure of profit. Intra-group licensing of IP can result in tax avoidance if the royalty payment is structured in a way that allows the payment to be received in a jurisdiction that either does not tax the IP income, or which subjects such income to a lower tax rate than the jurisdiction from which the payment is made.

As supply chains have grown with increasing globalisation, MNEs have sought to locate specific elements of their supply chain, such as marketing and logistics management (often referred to as “marketing hubs”) within entities in low-tax jurisdictions. Through strategic transfer pricing, these entities can be remunerated through a return on the costs incurred (mark-up basis), a return or commission based on the spend under management (e.g. total purchases) or a share of any gain arising from the contribution to the entity (e.g. a fee is charged as a percentage of the value generated/cost reduction achieved). By allocating the return earned by these entities through strategic transfer pricing in low tax jurisdictions, MNEs are able to reduce their overall effective tax rate.

The provision of intra-group services (e.g. insurance/headquarter services) from an entity located in a low-tax jurisdiction to an entity located in high-tax jurisdictions can result in tax avoidance if the payment is structured in a way that allows the payment to be received in a jurisdiction that either does not tax the service income, or which subjects such income to a lower tax rate than the jurisdiction from which the payment is made.

Holding companies are not necessarily located in low-tax jurisdictions for the purposes of profit shifting, but they can benefit from preferential tax treaty networks, which can ensure that dividend payments are received with either low or no withholding taxes whatsoever. Tax treaties between countries can reduce or exempt the application of withholding taxes on intra-group payments (e.g. dividends, interest, royalties, services) which can reduce the MNE’s overall effective tax rate. The ability to receive payments with no withholding tax collected at the source also impacts the location of IP and intra-group services.

The most important tax havensFootnote 8 for our sample in absolute terms are the Netherlands, Singapore, and Switzerland, followed by Luxembourg, and the Bahamas. The predominance of the Netherlands, Singapore and Switzerland is in line with other analyses of CbCR data (see Bratta et al., 2021, and Fuest et al., 2022a, 2022b, for European MNEs, Clausing, 2020, for U.S. MNEs). The outstanding role of the Bahamas is due to Shell and might thus be specific for our sample. We use the MNEs’ individual CbCR to extract their business activities reported in the top ten tax havens (ranked in terms of total sample profits) and compare them to the business activities reported in the top ten non-havens. 18 out of 35 groups report the principal business activities performed in each jurisdiction according to the OECD CbCR standard. The groups reporting high-risk activities in the top ten tax havens are Aegon, Anglo American, Eni, Orica, Randstad, Repsol, Rio Tinto, Shell, Vodafone and Wesfarmers. Among the remaining groups eight groups do not report high-risk activities in any of the top-ten tax havens, and 17 groups do not report business activities at all.

Figure 3 summarises MNEs’ business activities performed in tax havens and contrasts them with the business activities performed in non-haven jurisdictions. While most jurisdictions with important profits do host core functions, we also find that, in total, tax havens host a higher share of functions which are commonly used for aggressive tax planning. Conversely, non-havens host a higher share of core and other (lower-risk) activities.

Distribution of business activities in tax havens and non-havens. The figure plots how many times an activity is reported in the top 10 tax havens versus the top 10 non-havens (ranked according to the total value of profits reported). The activities comprise core activities (core), support services (sup), research and development (rd), regulated financial services (regfin), intellectual property holding (ip), intra-group finance (intrafin), group insurance (ins), marketing or trade hubs (hub), and holding companies (hold).

A clear pattern emerges for group insurance which our sample MNEs report 12 times in tax havens and only five times in non-havens, and marketing or trade hubs which are reported six times in tax havens but not in non-havens. Also, intra-group finance is more frequent in tax havens with 16 versus 11 times in non-havens. Among the tax havens, intra-group-finance is most frequently located in Luxembourg (Repsol, Rio Tinto, Shell, Vodafone, Randstad) and group-insurance in Bahamas (Repsol, Aegon, Shell, Wesfarmers). Hubs are located most frequently in Singapore (Anglo American, Rio Tinto, Shell) but also in Bahamas (Shell), Luxembourg (Vodafone), and Hong Kong (Vodafone).

Intellectual property and holding of shares seem to be more equally distributed across jurisdictions. Anglo American locates IP in Hong Kong but also in Australia, Canada, and the UK. Eni locates IP in the UK and the Bahamas, Shell in Switzerland, and Orica in Australia, the UK, and Singapore. Among the top 10 tax havens, the Netherlands and Luxembourg seem to be the most popular locations for holding companies with respectively nine and six MNEs reporting holding companies there.

An analysis of the distribution of high-risk and other activities at company level suggests that five companies are mainly responsible for the overall pattern: Randstad, Repsol, Rio Tinto, Shell, and Vodafone all report more high-risk activities in the top ten tax havens than in the top ten non-havens, and more core and other (lower-risk) activities in non-havens than in tax havens (Fig. 8 in the Appendix).

When quantifying MNEs’ general presence in tax havens, we focus on foreign affiliates’ profits in tax havens to avoid a potential bias introduced by profits in tax haven headquarters.Footnote 9 We compare the computed shares to the average share of foreign affiliates’ profits in tax havens in the aggregate CbCR data published by the OECD. The sample mean is 12% for our tax haven list and 8% for Gravelle’s list. This is slightly lower than 14% and 11% found in the aggregate CbCR data. To demonstrate that this difference is not driven by the important share of extractive industries in our sample, we compute also a sample mean excluding extractive industries which is even lower (9% for our list, 7% for Gravelle’s list).

We find that the share of overall profits reported in tax havens varies significantly in between groups ranging from 0% (for 10 MNEs of the sample) to 45% for Randstad. 30 out of 35 of the analysed MNEs report lower shares of profits in tax havens than what we find in aggregate CbCR data published by the OECD, according to our tax haven list. Only Randstad, Heimstaden, Shell, Vodafone, and Buzzi Unicem have higher shares.

The correction for equity-accounted profits does not make a big difference on average. This may be partly explained by the fact that equity-accounted profits look more important in percent of consolidated profits than in percent of total positive-only profits. For Shell, Buzzi Unicem and Heimstaden, the correction increases the tax-haven share by one to three percentage points, it lowers the share for Vodafone by 2 percentage points. Note, however, that our tentative correction for equity-accounted profits assumes that these profits occur in non-haven jurisdictions only (except for Buzzi UnicemFootnote 10) which cannot be verified for all companies, including shell, and should thus be interpreted with caution (Fig. 4).

Share of profits in tax havens. The figure plots the share of foreign affiliates’ tax haven profits in total profit for the 10 biggest groups and weighted means for the whole sample and a sub-sample of non-extractive groups. Values are averaged over available years. The bars refer to our tax haven list, the darker spikes refer to Gravelle’s (2015) list. The red bars present the average share of foreign affiliates’ tax haven profits as in the OECD aggregate CbCR statistics. The red dots plot the same share by headquarter jurisdiction. For certain headquarter countries it is not possible to calculate the share of profits in tax havens as the OECD data is not disaggregated at the jurisdiction level. The yellow dots present the share of profits in tax havens adjusted for equity-accounted profits.

4.2 Effective tax rates

The second risk indicator we analyse is the effective tax rate, both at MNE level \(\left( {{\text{ETR MNE}}_{i} } \right)\) and at country level \(\left( {{\text{ETR country}}_{j} } \right)\). MNEs characterised by low effective tax rates might employ tax avoidance strategies to minimise their tax burden, while countries where effective tax rates are low might be used as tax havens.

We calculate effective tax rates by MNE and for each country where MNEs are active. We take the means of observations by country and company over available years to reduce volatility and to not increase the weight of MNEs reporting in more than one year. For the baseline ETRs, we keep only positive profits which is most consistent for comparing the results with positive-profit sample from the aggregate OECD data. We set tax accrued to zero if it was negative on average. ETRs are defined as the ratio between the sum of reported income tax accrued and the sum of reported pre-tax profit (profit/loss before income tax) either by company or by country. For MNE i and country j the ETR is calculated as follows:

The MNEs’ worldwide effective tax rates \(\left( {{\text{ETR MNE}}_{i} } \right)\) are thus weighted averages which assign more weight to ETRs in locations where MNEs report relatively more profits. Similarly, the effective tax rates by country \(\left( {{\text{ETR country}}_{j} } \right)\) attach more weight to MNEs that account for higher shares of profit in that country.

We compute two alternative ETRs to incorporate insights from the comparison of CbCR profits to financial profits. To reduce the potential bias of equity-accounted profits, we subtract them from total CbCR profits for those MNEs which do not adjust the profits themselves (ETR 2). For the seven companiesFootnote 11 that likely include intra-company dividends in their CbCR profits, we subtract the difference of total CbCR profits (as calculated before dropping non-profitable observations) and the consolidated profits from the sum of positive CbCR profits (ETR 3). Both adjustments are only blunt proxies of the true necessary adjustments, because part of the subtracted profits might actually accrue to loss-making entities which we dropped from our analysis. However, they still serve to provide a rough idea of the potential bias in CbCR profits. To be as consistent as possible in the comparison to the aggregate CbCR statistics from the OECD, we also calculate an adjusted global ETR by subtracting 14.4% from the global profits, the amount that is estimated to be double-counted in US CbCR (Horst & Curatolo, 2020).

As shown in Fig. 5, the sample’s average global ETR is 25%Footnote 12 which is much higher than the global ETR of 14% from the aggregate CbCR statistics from the OECD. Only eight groups in the sample have an ETR below 14%. This result seems relatively robust to the different adjustments. For example, the adjustment for equity-accounted profits increases the sample mean by 0.5 percentage points, the correction for intra-company dividends increases the sample mean by 1.5 percentage points.

Global effective tax rates. The figure plots global effective tax rates for the largest 10 groups, weighted means of the full sample and a sub-sample of non-extractive groups, and a mean ETR based on OECD aggregate CbCR statistics. ETR_1 is the unadjusted ETR based on profit-making firms. ETR_2 adjusts for consolidated profits of equity-accounted joint ventures and associates when these are likely to be included in CbCR profits. ETR_3 adjusts for intra-company dividends. Note that the 10 largest groups do not include intra-company dividends in their CbCR profits. The red triangle plots the global average of groups headquartered in the same jurisdiction based on aggregate CbCR statistics

At company-level, the corrections have a more visible impact on the ETRs. The correction for equity-accounted profits affects the ETRs of Astm (ETR 1 of 37% versus ETR 2 of 30%), Shell (ETR 1 of 23% versus ETR 2 of 26%), Snam (19% vs. 21%), Wesfarmers (35% vs. 38%). The correction for dividends significantly increases the ETRs of Buzzi Unicem (from 10 to 15%), Evraz (from 15 to 28%), Orica (from 7 to 36%), Piaggio (from 25 to 42%), Snam (from 19 to 27%), and Sol (19% to 25%).

Altogether, it appears that companies which voluntarily published their CbCRs are more likely to pay higher ETRs than the world average. To rule out some potentially confounding factors, we undertake two additional robustness checks: Based on the OECD data, we compute global ETRs for MNEs headquartered in the same jurisdictions as the sample MNEs. Again, the sample ETRs are higher in most cases.

Another bias might come from the important share of extractive industries in our sample. For example, we find that the comparably high global ETRs of ENI and Repsol reflect high tax payments in resource-rich countries. The two MNEs concentrate a high share of their tax payments in resource-rich jurisdictions, some of them with very high ETRs: ENI’s top jurisdictions in terms of tax accrued are Libya, Algeria and Egypt. Similarly, Libya and Indonesia rank high for Repsol. High ETRs in these countries might be due to special tax regimes such as excess profits taxes which many countries apply in the extractive sector (Otto, 2017). For example, in 2018, Libya and Norway charged surtaxes on profits from the petroleum industry, implying composite nominal tax rates up to 65% and 78%. Algeria, Angola, Australia, and Nigeria also have special tax regimes for the oil and gas industry, including resource rent taxes, royalties, or additional profit taxes (EY, 2018). Also, in Indonesia, corporate income tax rates oil and gas industries or in mining may be calculated based on Production Sharing Contracts or Contract of Works (Deloitte, 2022) and might thus deviate from standard rates. To rule out that the sample’s high global ETR is merely a result of the high share of extractive industries in the sample, we compute an average ETR for a sub-sample of non-extractive MNEs. It is clearly lower than the full sample average (21%Footnote 13 versus 25%) but still visibly higher than the global ETR from aggregate CbCR statistics.

A negative correlation between the share of profits reported in tax havens and the global ETR might constitute an initial indication of profit shifting. Depending on the tax-haven share and ETR measures we employ, we find a negative correlation ranging between − 17% and − 26%. A relatively high presence in tax havens seems thus to be associated with lower effective global tax rates. The three outstanding MNEs in this regard are Buzzi Unicem, Heimstaden, Randstad, Shell, and Vodafone which combine comparably high shares of profits in tax havens with comparably low global ETRs.

4.3 Misaligned profits in tax havens

Although several companies report below world-average shares of profits in tax havens, their activities in tax havens are much more profitable than those in other jurisdictions. To assess the misalignment of tax-haven profit with reported activity more systematically, we compare each company i’s share of global profits in tax havens to its share of employees and tangible assets reported there. We compute misalignment by company i and country j as follows:

If the reported profits of an MNE in a given country are higher than profits predicted by that country’s share of the MNE’s total economic activity, this gives rise to ‘excess’ profit. If the reported profits are lower than the predicted profits based on the MNE’s economic activity, this gives rise to ‘missing profit.’ We obtain relative misalignment by dividing the absolute misaligned profits in each country by the profits MNEs actually report there.

When we measure economic activity in terms of the number of employees or tangible assets, most sample MNEs seem to report excess profits in tax havens which appear to be misaligned with economic activity to a varying extent (11–100%). This picture is only mixed for Atlantia, Orsted, Sol, Swiss Life, Philips, and Heimstaden which either report very low or negative misalignment for one of the economic activity measures.

When measured in terms of unrelated party revenues, misalignment is negative for 8 of the sample MNEs. This illustrates the sensitivity of the misalignment approach to the activity measure chosen. It also shows that tax havens attract a significantly higher share of the sample MNEs’ global unrelated party revenues compared to the share of MNEs’ global employees and tangible assets which these jurisdictions host. By strategically routing sales through tax havens, unrelated party revenues might already be over-reported in profit shifting destinations (Lafitte & Toubal, 2022). García-Bernardo and Janský (2021) suggest that even tangible assets may be strategically located as they find that US MNEs report the second highest value of tangible assets in Europe in Luxembourg.

A comparison of the sample means to the misalignment in terms of employees and tangible assets in OECD data, again suggests, that on average our sample’s profits are more aligned with economic activity than the global average. However, individual MNEs are also clearly above the global average. We find a negative correlation of misalignment with ETRs by group and jurisdiction for Ferrovial, Orica, Pearson, Randstad, Sol, Vodafone and Wesfarmer, and significant at the 10% level, which implies that these MNEs are more likely to report excess profits in jurisdictions where they pay less taxes and might be a first indication of profit shifting (Fig. 6).

Misalignment of profit and economic activity in tax havens by MNE. The figure shows to what extent aggregate profits reported in tax havens are misaligned with aggregate economic activity in terms of the number of employees and the value of tangible assets. If companies report a higher share of global profits than their share of global activity in tax havens, this gives rise to excess profits (positive misalignment). If companies report a lower share of profit than their share of global activity in tax havens, this gives rise to missing profits (negative misalignment)

4.4 Misalignment and effective tax rates

We further analyse the misalignment of profits and economic activity at country level to assess whether or not it correlates with average effective tax rates. As in recent applications of the misalignment methodology (Cobham & Janský, 2019) to CbCR data from large US MNEs (Garcia-Bernardo et al., 2022) and to public CbCR data from banks (Janský, 2020), we compute each country’s share in the total profits of the sample and compare it to each country’s share in the total economic activity. We use the number of employees as the preferred proxy for economic activity as employees are less likely to be strategically located compared to tangible assets and unrelated-party revenues.

We compute misaligned profit in each country j as follows:

As expected, we find that most tax havens exhibit both excess profit and very low ETR. This holds true for e.g. Bahamas, Bermuda, Hong Kong, Luxembourg, Malta, Singapore, and Switzerland, for which our sample ETRs range between 0 and 12%; and over 50% of profits reported there seem to be misaligned with economic activity. Other countries with relatively important excess profits include the Netherlands with an average ETR of 11%, Austria with an ETR of 12%. Countries with a share of resource rent in GDP above 5%, which we refer to as resource-rich countries, often have both high ETRs and relatively high excess profits, e.g. Norway, Nigeria, Libya, and Oman with ETRs in excess of 40% (Fig. 7). Countries with important missing profits are Brazil, Germany, Italy, South Africa, and Spain. Their ETRs range between 19 and 36%. Also, the USA have important missing profits but at a low ETR of 12%.

Misalignment and ETR by country. Misalignment is based on employee numbers. ETR_C is the effective tax rate calculated at the jurisdiction level. A country is considered resource-rich if it derives more than 5% of its GDP from resource rents according to the World Bank (2022). The bubble size varies with the absolute amount of profits which the sample MNEs report in each jurisdiction, where the biggest bubbles indicate the top quartile and the smallest bubble the bottom quartile of the distribution of sample profits across countries. For a better readability, 8 jurisdictions with misaligned profits below -500% are not displayed

For the total sample, misalignment and ETRs do not seem to be correlated. However, we find a correlation of -0.3 between relative misalignment and ETRs, significant at the 5%-level after excluding countries with a share of resources rent in GDP above 5%. When measuring economic activity in terms of tangible assets, we do not find any correlation. The high ETRs and excess profits of resource-rich countries seem to blur the expected negative correlation of ETRs and misalignment which points to the specific role of extractive industries in our sample.

How can the findings of excess profits and high ETR in several resource-rich countries be reconciled? Very high ETR may partly reflect measurement errors, e.g. due to the previously discussed differences in financial and tax accounting (Sect. 3.3). However, as discussed in Sect. 4.2. special tax regimes such as excess profits taxes often applied in the extractive sector (Otto, 2017) may also explain the high sample ETRs in resource-rich countries. Despite the high ETRs, the sample MNEs report above-average profits in these jurisdictions, in total but also per employee. Part of these profits may derive from resource rents rather than economic activity measured in terms of employee numbers. Most of them would also be identified as ‘excess profit’ countries if we used tangible assets as a proxy for economic activity (see Fig. 10 in the Appendix). The misalignment approach identifies them as ‘excess profits’ but this is very unlikely to be related to tax-induced profit shifting.

4.5 Semi-elasticities

The fact that ETRs and misalignment do not seem to be systematically correlated might indicate that our sample MNEs shift little profits to low-tax jurisdictions, on average. Still, some have located high-risk functions and non-negligible profits in tax havens. We thus reassess the correlation of profits and ETR in a more formalised way, controlling for potential confounding factors. A scatterplot of log profits by company and country and ETRs by country suggests a slightly positive correlation between the two variables (Fig. 11 in the Appendix).

We perform a simple regression analysis to estimate the semi-elasticity of the reported profits with regard to a tax incentive variable, as is usually done in related literature (Beer et al., 2021). We use our estimated ETR at country level to operationalize the tax incentive variable.Footnote 14 We use the log profit of each multinational group i in country j as the dependent variable and regress it on the estimated ETR of country j, including control variables at the MNE-country level and country level and a set of group dummy variables.

\(\tau_{j}\) is the ETR of country j, L and K are the number of employees and the tangible assets reported by group i in country j, X are country-level controls, which include GDP per capita, population size, and the share of natural resource rents in GDP. All country-level controls are taken from the World Bank (2022). The share of natural resource rent in GDP accounts for the fact that the extractive industries generate a natural resource rent which is less likely to be explained by labour and capital inputs. \(D_{i}\) are the 34 group dummies, leaving out Anglo American as the reference case.

As in Dowd et al. (2017), we compare the linear relationship (5) between profits and ETR to a quadratic form (6):

As we only have a small number of observations and pool them into a single cross section, our objectives in applying this tax semi-elasticity method are mostly to formalise the correlations between the variables that we observe in our descriptive analysis and to include additional covariates that help explain the global allocation of multinational profits.

We estimate a simple OLS regression. Controlling for MNE-country and country-level covariates, profits do not seem to be at all correlated with ETRs in the linear model. The coefficients are negative but very small and not significant. Allowing for a non-linear functional form we find a negative relationship between ETRs and the location of profits, but the coefficients are small and not very robust. For example, according to regression (2), at an ETR of 5% a one-percentage-point difference between countries would only explain 0.025% of the difference in reported profits. At an ETR of 25% the semi-elasticity would only be − 0.005.

In line with other researchers’ results, the nonlinear model would imply that the profit shifting incentive of a one percentage point difference between tax rates is higher at very low ETR levels and approaches zero at moderate ETR levels. For example, the ETRs of Luxembourg, Hungary, and Denmark, are 3%, 14% and 25%, respectively. Our results would imply that the tax difference of 11 percentage points between Luxembourg and Hungary explains a more important share of the distribution of profits between these two countries than the tax difference between Hungary and Denmark explains of the distribution of profits between Hungary and the Denmark. Intuitively, it makes sense that very low tax jurisdictions would attract most of the shifted profits, while jurisdictions with moderate tax rates would attract none or very little.

As expected, we find that the number of employees and assets are positively correlated with the profits reported by each multinational group in each jurisdiction. Population size correlates negatively. The share of natural resources rent in GDP is positive and significant as expected. As discussed in the misalignment section, our sample MNEs seem to make above-average profits in resource-rich countries which may confound the correlation of profits and ETR.

Again, we contrast our results with the global average by running a similar regressionFootnote 15 with the OECD aggregate CbCR Statistics (regression 7). The OECD aggregates data at the parent country and host country level while our data is at sub-group level, which limits comparability. Nevertheless, it is remarkable that the correlation of profits and the country-level ETRs seems more important in the OECD data.

For robustness checks, we repeat our sample regressions also with group-specific ETRs and with an extractive-industry interaction term. For the group-specific ETRs, we find a slightly negative linear relation with a coefficient of − 0.01 (regression 3). The coefficient of the group-specific ETR is more negative (− 0.03) when we include a quadratic term but the coefficient of the latter is not significant (regression 4). In regression (5) we include an interaction term of the country ETR with a dummy variable for extractive industries to test whether the relationship between reported profits and ETRs differs for MNEs from extractive and non-extractive industries. The coefficient of the country ETR remains unchanged and the interaction term is not significant. Similarly, the inclusion of the interaction term does not change the coefficient of the group-specific ETR (regression 6). The results are similar if we run the regressions with non-extractive MNEs only (regressions 13 and 14 in Table 8 in the Appendix). The low correlation of profits and ETRs does thus not seem to be a specific result for the extractive industry.Footnote 16

Using the nominal corporate tax rates (NCTR) instead of the ETRs (regressions 8 and 9 in Table 8 the Appendix) produces no significant results. As bigger MNEs might shift profits more aggressively, we limit the sample to the 10 biggest groups (regressions 10 and 11 in Table 8 in the Appendix). For the country ETR we find similar results as in regressions (1) and (2) but the coefficient of the ETR in the quadratic model is a little bit higher (− 0.05).

Our regression results suggest that our sample’s reported profits are on average negatively correlated with ETRs, which would be consistent with profit shifting activities. However, the estimated average coefficient size is much smaller than in other studies and not very robust. Even though the nonlinear relationship of profit and ETR makes sense intuitively, and is qualitatively in line with existing literature (e.g. Dowd et al., 2017; García-Bernardo & Janský, 2021), the small number and cross-sectional nature of observations do not allow us to identify profit-shifting behaviour of the sample MNEs. The relatively weak correlation profits and ETRs is, however, in line with our previous findings, i.e. the comparably high global ETRs and moderate tax-haven profits of the sample MNEs on average (Table 5).

4.6 Evaluation of tax risk indicators by company

Do more tax transparent MNEs avoid taxes less aggressively? Our analysis of tax risk indicators would support this view as our sample MNEs have higher global ETRs and most of them report a lower share of profits in tax havens than the global average. Also the average correlation of profits and tax rates looks comparably small. However, the limited sample size and the observed sample heterogeneity might shed doubt on such a general conclusion. We thus propose an evaluation of risk indicators by company to identify potential outliers more systematically.

To evaluate and compare tax risk indicators by company, we suggest simple thresholds for each indicator which allow us to identify some differences in tax risks between companies. Ideally, a very tax-aggressive company would locate high-risk functions in several tax havens (1), report an above-average share of profits in tax havens (2), and have a below-average global ETR (3). The profits in tax havens would not be aligned with economic activity reported there. Instead, profits would correlate with corporate tax rates (4). As these criteria depend strongly on their empirical operationalisation, we suggest more than one threshold for some of them.

For the high-risk activities in tax havens, we assess whether the group reports high-risk activities at all (1a) and whether it reports more high-risk activities in tax havens than in non-havens (1b). We define an above-average share of profits in tax havens relative to aggregate CbCR data (the population of large MNEs) and assess it for our tax haven list (2a) and Gravelle’s (2015) list (2b). We also compare two different versions of the group ETR to the global ETR from the aggregate CbCR statistics: The unadjusted ETR (3a) and the ETR adjusted for intra-company dividends (3b).Footnote 17 Finally, we consider profits as misaligned when profits in tax havens are misaligned with economic activity in terms of both employees and tangible assets (4a), and assess whether we find a correlation of misalignment with ETRs at group-level (4b).

We find that only one of the sample MNEs fulfils all of the ‘tax aggressiveness’ criteria across all operationalisations. Most have relatively low shares of tax-haven profits, high ETRs, and no correlation between profits and tax rates. Buzzi Unicem, Heimstaden, Randstad, Shell, and Vodafone are the only MNEs which surpass at least one threshold in three out of the four tax risk indicators. We disregard Orica even though it surpasses thresholds in three indicators because the ETR is only below the global average before adjusting for intra-company dividends and the share of profits in tax havens is below-average.

Buzzi Unicem reports an above-average share of profits in tax havens for both tax haven lists, below-average ETRs and its profits in tax havens are misaligned with economic activity even though not significantly correlated with ETRs. Heimstaden has above-average profits in tax havens according to our list, a below-average ETR and its profits in tax havens are misaligned with economic activity.

Randstad combines more high-risk activities in tax havens than in non-havens with an above-average share of profits in tax havens according to both lists. These profits are misaligned with economic activity and correlate with ETRs. Similarly, Shell locates more high-risk activities in tax havens than in non-havens and reports an above-average share of profits in tax havens. Its tax haven profits are misaligned with economic activity but do not seem to correlate with ETRs. The most outstanding group is Vodafone as it locates more high-risk activities in tax havens than in non-havens, reports an above-average share of profits in tax havens and a below-average global ETR. In addition, the profits in tax havens are misaligned with economic activity and correlate with ETRs.

Table 6 illustrates the evaluation results for the top 10 MNEs. A full table with all groups can be found in the Appendix (Table 9).

5 Conclusion

In this paper, we explore voluntarily published CbCRs by 35 MNEs which provide an exceptional level of corporate tax transparency on a global scale. We assess the quality of the data by comparing it to consolidated financial accounts and discuss the role of double-counting of profits, the inclusion of associate and joint venture profits, and other issues which may impede a meaningful interpretation of CbCR data. Based on several tax risk indicators, we assess to what extent our sample MNEs may differ from the global population of large MNEs as included in the aggregate CbCR data. We further provide a tentative framework to evaluate tax risk indicators across sample MNEs and assess their potential overall tax aggressiveness even in the absence of a clear identification of profit shifting.

Our analysis confirms that CbCR data need to be interpreted with some caution, as reporting across MNEs is not uniform and tax risk indicators may be biased by dividends or profits of equity-accounted entities. However, it seems that many MNEs voluntarily publishing CbCRs are aware of these risks as they tend to avoid the double-counting of profits in the form of dividends, and some even correct for profits of associates and joint ventures. For those who do not, we find that equity-accounted profits account for 9% of consolidated profits on average. This share can be significantly higher for individual companies. However, as we apply the correction to the sum of positive CbCR profits which is mostly higher than consolidated profits, the correction effect is very moderate and leads to at best gradual adjustments of individual and average risk indicators. The correction for intra-company dividends is quantitatively more important but concerns only seven of the smaller MNEs and has thus only limited effects on the average risk indicators.

These reporting problems are likely to be avoided as the reporting standard improves but some conceptual gaps between financial profits and taxable profits remain. While loss carryover can to some extent be addressed by averaging observations over several years, a certain degree of uncertainty with regard to ETRs seems to be unavoidable as long as MNEs’ tax accounts are kept confidential. Some MNEs provide additional qualitative information to explain low tax payments in individual countries but the data does not allow for a systematic correction of the calculated ETRs by country. Nevertheless, the voluntary publishing of CbCRs may in itself be regarded as a major step towards greater transparency.

The early publishers of CbCR, which we analyse in this paper, generally seem to score low on typical tax risk indicators. Most of the sample MNEs report comparably low profits in tax havens and moderate-to-high global ETRs. We also find that they more frequently locate high-risk functions in tax havens than in other jurisdictions and also find some degree of correlation between the location of profits and ETRs. This might be indication of profit shifting, but the correlation coefficients seem low compared to other studies when controlling for covariates and not robust across specifications. As some tax risk indicators vary substantially between MNEs, we provide a tentative assessment of overall tax aggressiveness by company and find that only one company fulfils all proposed criteria completely. Five MNEs stand out as they surpass at least one threshold in three out of four criteria for tax aggressiveness.

First, we conclude that despite all the discussed limitations early publishers of CbCRs tend to report better than what quality assessments of aggregate CbCR statistics suggest. Second, early publishers of CbCR seem to avoid taxes less aggressively on average than the global average. An evaluation of tax risk by company suggests that this conclusion holds for the great majority of MNEs in the sample while some clear outliers can be identified. Both results seem plausible: MNEs avoiding tax less aggressively might fear tax transparency less and thus decide to publish their reports. This would be in line with Adams et al. (2022) who find indication that less tax-aggressive MNEs tend to be more tax transparent. At the same time, MNEs avoiding taxes less aggressively might have an interest in preventing misleading interpretations by the public and thus tend to report more meaningful numbers.

A potential confounding factor might be that the high sample ETRs are the result of the correct accounting of dividends and associate and joint venture profits, which may distinguish our sample from the average MNE included in aggregate CbCR data. As publication of EU-wide CbCR will become mandatory in 2024, it might become possible to assess differences between MNEs that publish voluntarily and those which are forced to publish more systematically.

Notes

This concerns Teck which reports extremely high total profits in 2020 and St. James’s Place for the year 2020 because of zero employees globally. (Note that an original CbCR report for St. James’s Place 2020 is not available online, anymore, at the time of writing.).

Vodafone argues that “the OECD report does not provide an explanation of the nature of the activity, or activities, that take place in a jurisdiction, which we believe is vitally important in order to understand the context of a multinational company’s CbCR” and that the profit before tax included in their OECD CbCR report “represents the total taxable revenue in each country less expenditure and reflects the starting point for a corporate tax calculation. However, it does not reflect the profit on which we pay tax, as the impact of the tax laws in each jurisdiction are not included, and therefore, tax exempt gains and losses are not taken into account in this number. For example, this number includes dividends received, which are usually tax exempt, as well as all gains and losses arising on the disposal or writing down of a business. We exclude these tax-exempt gains and losses in our voluntary reporting, as these amounts are usually exempt from tax by the standard tax laws of a country. Therefore, the amounts reported in our voluntary report are more closely related to the amounts on which we pay tax in each jurisdiction.” (Vodafone, 2018).

Our final averaged sample includes 14 observations with ETR > 100%. We do not drop these outliers because our tentative corrections for intra-company dividends and equity-accounted profits rely on information from the financial accounts. Dropping observations increases the discrepancy between CbCR totals and consolidated variables which would make our corrections based on consolidated information more inconsistent. For robustness, we compute global ETRs also without these outliers and report results in the footnotes.

Note that Ferrovial has an exceptionally high share of equity-accounted profits (63%) among the MNEs including equity-accounted profits in CbCR profits (“includers”). Ferrovial highlights this fact when computing its own global ETR but does not adjust the reported CbC profits accordingly (Ferrovial 2021).

Luxembourg.

This might be linked to the GRI standard which requires companies to explain why their effective tax rates differ from statutory rates.

We use the tax haven list by Gravelle (2015) and add Belgium, Hungary and the Netherlands, as according to the European Parliament’s special tax crime committee (2019) they also display tax haven traits and facilitate aggressive tax planning. Gravelle’s list includes Andorra, Anguilla, Antigua and Barbuda, Aruba, Bahamas, Bahrain, Barbados, Belize, Bermuda, Cayman Islands, Cook Islands, Costa Rica, Cyprus, Dominica, Gibraltar, Grenada, Guernsey, Hong Kong, Ireland, Isle of Man, Jersey, Jordan, Lebanon, Liberia, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Macao, Maldives, Malta, Marshall Islands, Mauritius, Monaco, Montserrat, Nauru, Netherlands Antilles, Niue, Panama, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Samoa, San Marino, Seychelles, Singapore, St. Kitts and Nevis, Switzerland, Tonga, Turks and Caicos Islands, Vanuatu, British Virgin Islands, and U.S. Virgin Islands.

Headquarter profits are more likely to include double-counted profits (see Sect. 3.1) and four sample MNEs are headquartered in the Netherlands which would produce extreme tax-haven shares for them.

Buzzi Unicem reports equity-accounted profits in Luxembourg but they account for less than 0.3% of their profits in Luxembourg so that subtracting these profits from the enumerator has hardly any effect.

Atlantia, Orica, Evraz, Piaggio, Buzzi Unicem, Snam and Sol.

This average ETR decreases by less than one percentage point when we drop observations with ETRs > 100% from the sample.

The non-extractive ETR drops by one percentage point when we exclude observations with ETR > 100% from the sample.

For the regressions, we exclude observations with ETRs above 100%. Note that including them would produce even weaker or no correlations.

Dependent and independent variables are identical but we include headquarter country dummies instead of group dummies.

Due to the specific tax rules applicable in the extractive industries, it might make sense to also use sector-specific ETRs as benchmark ETRs to assess an MNE’s tax aggressiveness. For example, PWC (2015) finds that the average ETR of the global oil and gas sector was 31.5% on average over the years 2011–2013 which was higher than in other sectors. Unfortunately, comparable consistent and up-to-date benchmarks are not available for all industries represented in our sample.

References

Adams, J., Demers, E. & Kenneth, J. (2022). Tax aggressive behaviour and voluntary tax disclosures in corporate sustainability reporting. School of Accounting & Finance, University of Waterloo. April 2022. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4284813.

Aliprandi, G., Borders, K., Gabriel, F. & von Zedlitz, G. (2022). Public country-by-country reports: A new dataset. EU Tax Observatory.

Aliprandi, G. & von Zedlitz, G. (2023). Benchmarking benchmarking country-by-country reports. TRR 266 Accounting for Transparency Working Paper Series No. 122.

AngloAmerican (2019a). Country by country reporting publication. Available at: https://www.angloamerican.com/~/media/Files/A/Anglo-American-Group/PLC/investors/annualreporting/2019/anglo-american-country-by-country-report-2018.pdf

AngloAmerican (2019b). Integrated annual report 2018. Available at: https://www.angloamerican.com/~/media/Files/A/Anglo-American-Group/PLC/investors/annual-reporting/2019/aaannual-report-2018.pdf

Barake, M., Chouc, P.-E., Neef, T., Zucman, G. (2021). Revenue effects of the global minimum tax: country-by-country estimates. EU Tax Observatory Note No. 2. https://www.taxobservatory.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Note-2-Revenue-Effects-of-the-Global-Minimum-Tax-October-2021.pdf.

Barake, M. (2022). Tax planning by European banks. EU Tax Observatory Working Paper No. 9.

Beer, S. & Loeprick, J. (2018). The cost and benefits of tax treaties with investment hubs: findings from Sub-Saharan Africa. IMF Working Paper No. 2018/227. Available at: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2018/10/24/The-Cost-and-Benefits-of-Tax-Treaties-with-Investment-Hubs-Findings-from-Sub-Saharan-Africa-46264.