Notes

The equivalence follows by standard first-order bi-conditionals: ∀x[A(x) → ∃y[B(y)] ↔ ∀x[¬A(x) v ∃y[B(y)]] ↔ ∀x[¬A(x)] v ∃y[B(y)] ↔ ¬∃x[A(x)] v ∃y[B(y)] ↔ ∃x[A(x)] → ∃y[B(y)].

Herburger (2000) subsequently (and independently) proposes an analysis of adverbial quantification similar to Rothstein (1995), appealing to a one-to-one mapping of events. Herburger (2000) doesn’t treat the issue of compositionality that is a focus of attention below, hence my remarks are directed to Rothstein (1995) as a point of comparison. See also Kratzer (2004) for application of matching quantification in a somewhat different context.

As Rothstein (1995) discusses, Boolos-type examples like (1-a) raise questions not arising with examples of the (5a-d) type, so I put them aside for the purposes of this article.

See Rothstein (1995, 3.3.2) for the full details of this composition.

See Sect. 3 for more on thematic uniqueness.

I am grateful to Lucas Champollion for discussion on this point.

Put more generally, if a class of elements X takes its denotations in the space Da<b,t>, and if for some α∈X it happens there is also a corresponding function f ∈ \(\mathrm{D}^{\mathrm{b}}\)<a,t>, it doesn’t follow that α should denote f. We might still want to give α a denotation in \(\mathrm{D}^{\mathrm{a}}_{<\mathrm{b},\mathrm{t}>}\), simply placing a constraint on α.

An anonymous NALS reviewer observes that speakers can use “funnily” or “for whatever reason” in these circumstances precisely to indicate they are not in a position to supply a “witness” injection verifying their existential assertion—that the latter is purely quantificational, not specific.

An anonymous NALS reviewer raises an interesting question in the context of Rothstein’s free variable analysis. Reformulating examples slightly, the reviewer notes an apparent entailment asymmetry between the matching sentence in (i-a) and the at-least-as-many-as sentence in (i-b):

-

(i)

-

a.

(Last year) Every time John turned on the heat, he turned on the air conditioning.

-

b.

(Last year) John turned on the air conditioning at least as many times as he turned on the heat.

-

a.

Whereas (i-a) entails (i-b), the converse doesn’t seem to hold. If John turned on the air conditioning 12 times and the heating 11 times, this seems enough to verify (i-b), but it does not seem adequate to verify (i-a). Informally, more of a connection seems required for (i-a). This result is potentially problematic for the existential quantifier analysis of matching, since the entailment from (i-b) to (i-a) is predicted under elementary results of set theory. Specifically, the entailment from (ii-b) to (ii-a) follows from (ii-c).

-

(ii)

-

a.

For every Q, there is a P.

-

b.

There are at least as many Ps as Qs.

-

c.

∀P∀Q[∣P∣ ≥ ∣Q∣ → ∃f: P → Q], where f is an injection.

-

a.

On the other hand, if we adopt Rothstein’s analysis, we block the entailment, since although a cardinal inequality between P and Q entails the existence of some injection f between their memberships, it doesn’t entail any specific M, which is what the Rothstein analysis requires.

While I do not have a full analysis of this point, I note two observations in response. The first is that while I agree that (i-b) doesn’t seem to entail (i-a) in the situation stated, my judgment for (iii), the “Boolos-equivalent” of (i-a), is quite different.

-

(iii)

For every turning on of the heat by John, there was a turning on of the air-conditioning by John.

For me, (i-b) does in fact entail (iii). Minimally therefore, the contrast between (i-a) and (iii) suggests that the assumption that Rothstein (1995) makes, and that I have followed, regarding the equivalence of “Boolos sentences” like (iii) and adverbial quantifications like (i-a) is mistaken—and that there are other semantic differences involved.

At the same time, I would make a second and competing observation, namely that in certain specific circumstances, matching sentences of the form in (i-a) do seem to be entailed (or nearly so) by at-least-as-many-as sentence like (i-b). Consider (iv-a), a variant of an old saying expressing the relation between disappearing and emerging opportunities in life.

-

(v)

-

a.

In life, every time an opportunity closes, a new opportunity opens up.

-

b.

In life, the number of opening opportunities is ultimately at least as many as the number of closed opportunities.

-

a.

The truth conditions here seem very close. The individuals matched (opportunities) are the same and their identities are not relevant (i.e., both indefinites are read non-specifically). Furthermore, the statements are generic. The main difference is the temporal relation implicit in (iv-a). Plausibly this arises from the dual temporal reference in (iv-a) vs. (iv-b) and the need to order these with respect to each other. In (iv-a) they can be understood as simultaneous or successive. In (i-a) there is a strong inclination to read the events as successive (unless John’s temperature controls are arranged to execute both simultaneously). Similar observations apply to (via-b) and (viia-b).

-

(vi)

-

a.

Every time I find a sock, I lose a sock.

-

b.

The number of my sock-losings is at least as many as the number of my sock-findings.

-

a.

-

(vii)

-

a.

Every time a star dies, a star is born.

-

b.

The number of star-births is at least as many as the number of star-deaths.

-

a.

I conclude (following the NALS reviewer, I believe) that although Rothstein (1995) is basically correct in analyzing examples like (i-a) as counterpart to Boolos-type examples like (iii), there are remain some differences suggesting they should not be entirely assimilated. I must leave this topic for future exploration.

-

(i)

See Heycock (2022) for recent discussion of the syntax of these constructions.

Here I assume the same syntactic simplifications as Rothstein (1995) does for purposes of discussion. The view that the sentence-initial adverbial originates in VP is motivated by the interpretation of VP ellipsis in examples like (i), where it seems possible to construe [VP e] as ‘answers every time Mary phones’.

-

(i)

Every time Mary phones, John answers and Bill does [VP e] too.

This suggests that a more correct syntax for (5-a) would be as in (ii), involving a lower copy of the preposed adverbial, where the lower copy is interpreted in situ at LF, and where again, no variable binding is involved.

-

(ii)

Every time Mary phones, John [VP answers

].

].

I leave the syntactic details aside.

-

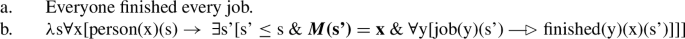

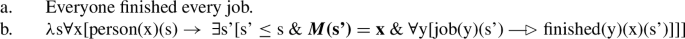

(i)

Kratzer (2004) also proposes that every contains a function that matches events—in her analysis, situations. However, in Kratzer’s formulation, matching relates quantifier restrictions, not restriction and scope. For example, Kratzer analyzes (i-a) as in (i-b), where s and \(s'\) range over situations, and where M is Rothstein contextually understood matching function,

-

(i)

Note here that what is matched is the “resource situation” \(s'\) associated with the nominal in the lower quantifier (job) and the individuals x denoted by the nominal in the higher quantifier (person). See Schwarz (2009) for useful discussion and elaboration of these ideas and see Chatain (2022) for an application of Kratzer’s proposal to cumulativity effects with every.

-

(i)

Given all({x: flies(x)}, {y: bird(y)}) iff all({x: flies(x)}∩{y: bird(y)}, {y: bird(y)}).

See fn. 18 for further discussion.

The latter move is not open to Rothstein (1995). Because she needs the main clause event to be existentially bound eventually, and because she treats every as classical, closure in the structure must result by an independent operation, like the one she posits in the semantics of CP. It’s worth noting that Rothstein’s association of closure with CP is dubious, if only because CP projection is also possible in the adverbial clause, where she precisely does not want closure to occur (Every time that…). In any case, the issue of existential binding of the main clause event does not arise in the quantifier analysis, since this binding is provided by matching every itself (recall (29-h)).

An anonymous NALS reviewer notes general issues with existential event closure accounts arising with negation examples like Every time Mary phones, John won’t pick up the phone (Landman 2000). While I acknowledge such issues, I do not attempt to address them since this would require a broader discussion of negation in event semantics. For a very thorough recent treatment of this topic, see Schein (2020).

I am grateful to an anonymous NALS reviewer for drawing attention to this point.

Languages showing semantic case include members of the Finno-Ugric family and various Australian languages (Blake 2001).

See Larson (1985) for details and Larson (2014) for further elaboration, as noted by an anonymous NALS reviewer. See also Altshuler et al. (2020) for an interesting formal development of the idea that theta-relations are born directly by argument and adjunct nominals and not assigned by heads like P.

It may be possible to simplify this distributional statement so that matching every selects oblique time, but classical every selects all variants of time, including the oblique one. The issue turns on the analysis of examples like (i)–(ii) (slightly modified from Rothstein 1995):

-

(i)

Every time Mary watches Saw, she watches it with John.

-

(ii)

Every time Mary drinks whisky, she drinks Laphroaig.

As Rothstein notes, the event predicates—watching and drinking, respectively—are identical in the adverbial and main clauses. Furthermore, the individuals bearing theta-relations in the adverbial clause of each (e.g., Mary/agent, Saw/theme in (i)), are individuals bearing the very same theta-relations in the main clauses. Hence thematic uniqueness does not exclude the e’s from being identified as the same in this case. Since these are adverbial constructions, Rothstein must analyze them as involving matching with M simply understood contextually as identity (iiia-b):

-

(iii)

-

a.

∀e[watching(e) & agent(e,#Mary) & theme(e,#Saw) → ∃e’[watching(e’) & agent(e’,#Mary) & theme(e’,#Saw) & with(e’,#John) & M(e’) = e]]

-

b.

∀e[drinking(e) & agent(e,Mary) & theme(e,#whiskey) → ∃e’[drinking(e’) & agent(e’,#Mary) & theme(e’,#Laphroaig) & M(e’) = e]]

-

a.

In the current analysis, it would be possible to analyze (i)–(ii) as involving classical every combining with oblique time and quantifying over events of the adverbial and main clauses directly, without matching (iva-b).

-

(iv)

-

a.

∀e[ watching(e) & agent(e,#Mary) & theme(e,#Saw) → watching(e) & agent(e,#Mary) & theme(e,#Saw) & with(e,#John)]]

-

b.

∀e[ drinking(e) & agent(e,#Mary) & theme(e,#whiskey) → drinking(e) & agent(e,#Mary) & theme(e,#Laphroaig)]]

-

a.

At present, I do not see a way to adjudicate between the matching every + contextual identity vs. classical every analyses of (i)–(ii). Intuitions about event identity seem insufficient. In (v), which differs minimally from (i), there is a clear intuition for me that the events are the same. But under thematic uniqueness this intuition must be deceptive, since the events in the adverbial and main clauses of (v) have different agents.

-

(v)

Every time Mary watches Saw, John watches it with her.

I must leave this issue unresolved for present pending further investigation.

-

(i)

See, for example, Higginbotham (2004).

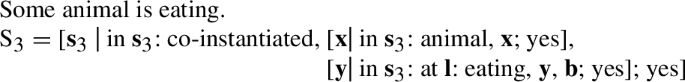

The idea of quantificational states has precedent. Barwise and Perry (1985) offer such a notion within Situation Semantics; see (i), where the s variables range over situations.

-

(i)

In this framework, motivation is largely “architectural”. Since sentences describe situations, quantificational sentences must describe quantificational situations; hence, there must be quantificational situations for sentences to describe, and so on.

-

(i)

Note that introduction of quantificational states also predicts that reference to such states should be possible, a classic Davidsonian point. (i) is a potential example.

-

(i)

The pronoun it in the second conjunct evidently refers to John’s “condition”, which is plausibly construed as the quantificational state introduced by the first conjunct.

-

(i)

Again, we note that reference to quantificational states seems available in these cases. Consider (i).

-

(i)

Did you hear it/that/the pattern? Mary always stresses her final syllable!

The NPs it/that/the pattern in the first conjunct plausibly refer—not to an individual sound or a set of sounds, but rather—to Mary’s prosodic pattern. This is plausibly construed as the quantificational state described in the second conjunct.

-

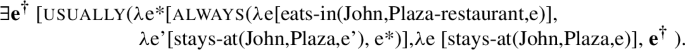

(i)

Note that the restriction argument of always, corresponding to anaphoric then in (69-a), is understood as bound to, and hence identical in content with, the restriction argument of the higher adverb usually (λe[John-stay-at-P(e)]).

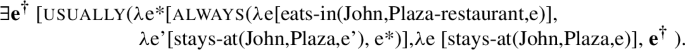

We are focusing here on the embedded adverbs. Of course, it follows by this logic that the higher adverbs usually and often must themselves introduce event variables, so that the final truth conditions for (70-a) will be as in (i) below, and analogously for (70-b). Here the e†-variable corresponding to the higher usually is bound by existential closure.

-

(i)

-

(i)

See Pietroski (2005), however, for a recent alternative analysis.

Again, see also Herburger (2000).

I am grateful to an anonymous NALS reviewer for suggestions helping me to clarify and simplify presentation in the next two sections

The assumptions made here and in the next paragraph are standard. The familiar lambda expression in (31-a), repeated below as (i), has the universal quantifier combine first with its restrictor argument Q and subsequently with its scope argument P:

-

(i)

λQλP∀x[Q(x) → P(x)].

-

(i)

An anonymous NALS reviewer observes that classical every can also be derived by imposing on r, s the equivalent constraint that (∀x)(∀y) (r(x) = s(y) → x = y).

I am indebted to an anonymous NALS reviewer for the format for lexical quantifier rules in (96)–(98). Another NALS reviewer notes that argument separation, as given in this analysis is wholly in the metalanguage—it is “subatomic” in the sense of Parsons (1990). This is correct, but one might develop these ideas differently. As discussed below, the restriction injection looks similar, if not identical, to Krifka’s incremental theme relation. If the latter is a specific thematic relation, and not simply any injection with the algebraic properties Krifka assigns it, then one might substitute that definite function ℛ for the existentially quantified r in (95)–(97). The quantifiers could then be distinguished by their scope functions. \(\mathscr{S}_{\forall}\), for example, would be that injection into e such that |IMAGE(ℛ) − IMAGE(\(\mathscr{S}_{\forall}\))| = 0. I leave such developments to future work.

See the immediately following Sect. 4.3.1 for more on this question.

It is interesting to note that languages do appear to draw on such abstraction in certain cases. Dixon (1971) reports on a special sublanguage of Dybirbal, called Dyalŋuy, which is known to all Dybirbal speakers and is used in speaking to certain restricted classes of kin. Dixon reports that Dyalŋuy has a total vocabulary of approx. 400 items, but can nonetheless express everything that speakers can express using the full language. One strategy that speakers employ with Dyalŋuy is to use a single generalized verb in place of a class of more specialized forms; thus, a single Dyalŋuy verb substitutes for all the Dybirbal verbs of cutting (‘sever,’ ‘slice,’ ‘carve,’ etc.); likewise, a single Dyalŋuy verb substitutes for all the Dybirbal verbs of expressing transfer of possession. (103-b) might represent a plausible interpretation for such a form.

The existence of an injection of W into B, as in (104-b), continues to be guaranteed by the existence of inverses and the fact that composition of two injections is an injection, as discussed earlier.

Krifka’s analysis is developed in attractive ways by Beavers (2002) and Wechsler (2005). The former extends it to an account of resultative path constructions like Mary pounded the grain into flour, wherein the structure of path phrases like into flour is injected into event structure. The latter extends it to an account of resultative secondary predicate constructions like Mary wiped the table dry, wherein the degree structure of closed-scale adjectives like dry is injected into event structure.

I am grateful to Paul Pietroski for suggesting this connection. There remains considerable debate as to whether exhaustive pairing in children is due to the lexical meanings they assign, the pragmatic inferences they draw, or even confounds in the experiments. Furthermore, exhaustive pairing does not seem to occur in all syntactic contexts (see, e.g., Aravind et al. 2017). Hence the suggestion made here is to be regarded as tentative. I am grateful to an anonymous NALS reviewer for discussion on this point.

To illustrate a potential test, consider the storyline “Mary sometimes plays inside and sometimes plays outside, but she always plays inside when it snows” followed by four pictures, one showing her outside and it not snowing, two showing her playing inside and it snowing, and one showing her playing inside and it not snowing. Do children that exhibit exhaustive pairing in the nominal domain also show it in such cases as well, so that they correlate inside-play strictly with snowing?

References

Altshuler, Daniel, Terry Parsons, and Roger Schwarzschild. 2020. A course in semantics. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Aravind, Athulya, Jill de Villiers, Peter de Villiers, Christopher Lonigan, Beth Phillips, Jeanine Clancy, Susan Landry, Paul Swank, Michael Assel, Heather Taylor, Nancy Eisenberg, Tracey Spinrad, and Carlo Valiente. 2017. Children’s quantification with every over time. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics 2: 43. https://doi.org/10.5334/gjgl.166.

Barwise, Jon, and Robin Cooper. 1981. Generalized quantifiers and natural language. Linguistics and Philosophy 4: 159–219. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00350139.

Barwise, Jon, and John Perry. 1985. Situations and attitudes. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Beavers, John. 2002. Aspect and the distribution of prepositional resultative phrases in English. CSLI, Stanford University. LinGO Working Paper no. 2002-07. http://lingo.Stanford.edu/working-papers.html.

Blake, Barry. 2001. Case, 2nd edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Boolos, George. 1981. For every A there is a B. Linguistic Inquiry 12: 465–467.

Brooks, Patricia, and Irina Sekerina. 2005/2006. Shortcuts to quantifier interpretation in children and adults. Language Acquisition 13(3): 177–206. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20462462.

Carlson, Greg. 1984. Thematic roles and their role in semantic interpretation. Linguistics 22: 259–279. https://doi.org/10.1515/ling.1984.22.3.259.

Chatain, Keny. 2022. Articulated homogeneity in cumulative sentences. Journal of Semantics 39: 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1093/jos/ffab019.

Davidson, Donald. 1967a. The logical form of action sentences. In The logic of decision and action, ed. Nicholas Rescher, 81–120. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Davidson, Donald. 1967b. Causal relations. Journal of Philosophy 64: 691–703. https://doi.org/10.2307/2023853.

Dixon, R. M. W. 1971. A method of semantic description. In Semantics: An interdisciplinary reader in philosophy, linguistics and psychology, eds. D. Steinberg and L. Jakobovits, 436–482. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Herburger, Elena. 2000. On what counts. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Heycock, Carolyn. 2022. Before and after when. Stony Brook University Linguistics Colloquium, April 8, 2022.

Higginbotham, James. 1983. The logic of perceptual reports: An extensional alternative to situation semantics. Journal of Philosophy 80: 100–127. https://doi.org/10.5840/jphil198380289.

Higginbotham, James. 1985. On semantics. Linguistic Inquiry 16: 547–593. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4178457.

Higginbotham, James. 2004. The English progressive. In The syntax of time, eds. J. Gueron and J. Lecarme, 329–358. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Inhelder, Bärbel, and Jean Piaget. 1958. The early growth of logical thinking from childhood to adolescence. New York: Basic Books.

Johnston, Michael. 1994. The syntax and semantics of adverbial adjuncts. Ph.D. dissertation, University of California at Santa Cruz.

Kratzer, Angelika. 2004. Covert quantifier restrictions in natural languages. Talk given at Palazzo Feltrinelli in Gargnano, June 11, 2004.

Krifka, Manfred. 1989. Nominal reference and temporal constitution. In Semantics and contextual expression, ed. T. Bartsh, 75–115. Dordrecht: Foris.

Krifka, Manfred. 1993. Thematic relations as links between nominal reference and temporal constitution. In Lexical matters, eds. I. Sag and A. Szabolsci, 29–53. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Krifka, Manfred. 1998. The origins of telicity. In Events and grammar, ed. S. Rothstein, 197–235. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Krynicki, Michał, and Alistair H. Lachlan. 1979. On the semantics of the Henkin quantifier. The Journal of Symbolic Logic 44: 184–200. https://doi.org/10.2307/2273726.

Landman, Fred. 2000. Events and plurality: The Jerusalem lectures. Dordrecht: Springer.

Larson, Richard. 1985. Bare-NP adverbs. Linguistic Inquiry 14: 595–621. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4178458.

Larson, Richard. 2014. On shell structure. London: Routledge.

Mittwoch, Anita. 2011. Do states have Davidsonian arguments? Some empirical considerations. In Event arguments: Foundations and applications, eds. C. Maienborn and A. Wöllstein, 69–88. Boston: Max Niemeyer Verlag.

Parsons, Terence. 1985. Underlying events in the logical analysis of English. In Actions and events: Perspectives on the philosophy of Donald Davidson, eds. E. Lepore and B. McLaughlin, 235–267. Oxford: Blackwell.

Parsons, Terence. 1990. Events in the semantics of English. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Parsons, Charles. 2008. Mathematical thought and its objects. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Philip, William. 2011. Acquiring knowledge of universal quantification. In Handbook of generative approaches to language, eds. J. de Villiers and T. Roeper, 35–394. Dordrecht: Springer.

Pietroski, Paul. 2005. Events and semantic architecture. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rothstein, Susan. 1995. Adverbial quantification over events. Natural Language Semantics 3: 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01252883.

Schein, Barry. 2020. Negation in event semantics. In The Routledge companion to philosophy of language, eds. G. Russell and D. Graff Fara, 280–294. Oxford: Routledge.

Schwarz, Florian. 2009. Two types of definites in natural language, PhD dissertation, University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Schwarzschild, Roger. 2022. Pure event semantics. Unpublished manuscript. lingbuzz/006888.

Vlach, Frank. 1983. On situation semantics for perception. Synthese 54: 129–152. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20115829.

Wechsler, Steven. 2005. Resultatives under the event-argument homomorphism model of telicity. In The syntax of aspect: Deriving thematic and aspectual interpretation, eds. N. Erteschik-Shir and T. Rapoport, 255–273. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Acknowledgements

For comments and questions, I thank audiences at MIT and the CUNY Graduate Center, and participants at the 2016 Goethe University Frankfurt Workshop on the Syntax and Semantics of the Nominal Domain, and the 2022 International Conference on Adverbial Clauses, University of Cologne, Germany. I thank Lucas Champollion, Norbert Hornstein, Angelika Kratzer, Peter Ludlow, and Paul Pietroski for comments on earlier versions of this manuscript. And I thank Susan Larson for redrawing the illustration in (111). I am particularly indebted to three anonymous NALS reviewers for comments and suggestions have greatly improved this paper. Finally, I dedicate this article to the memory of Susan Rothstein, to whose work it is thoroughly and gratefully indebted.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The author has no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Larson, R.K. Quantification, matching and events. Nat Lang Semantics 32, 269–313 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-023-09216-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-023-09216-x

].

].