Abstract

Stress has long been implicated in relation to problem gambling and gambling disorder. However, less is known about the psychological processes that link stress to problem gambling through other known correlates, including outcome expectancies and maladaptive coping. The current study tests a moderated mediation model whereby the effect of stress on problem gambling was hypothesized to be mediated by escape outcome expectancies, with this mediation effect moderated by maladaptive coping. Participants (N = 240; 50.2% male, Mage = 32.76 years; SDage = 11.35 years) were recruited from an online crowdsourcing platform and provided responses on the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995), the Problem Gambling Severity Index (PGSI; Ferris & Wynne, 2001), escape subscale of the Gambling Outcome Expectancies Scale (GOES; Flack & Morris, 2015) and the Brief COPE (Carver, 1997). The model was tested using Hayes’ (2018) PROCESS macro, revealing a significant moderated mediation effect of the stress-escape path by maladaptive coping, showing that the effect was significant when maladaptive coping was high. The findings provide support for escape outcome expectancies as being a potential mechanism through which the stress-problem gambling relationship may operate specifically, influenced by how gamblers are engaged in maladaptive coping generally. There is a need to further investigate the potential for combining gambling outcome expectancy challenges with methods to reduce maladaptive coping or develop more adaptive responses in the face of stress among problem gamblers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Stress is often identified as a risk factor in the development and maintenance of problem gambling. Indeed, a range of studies have linked various sources of stress and stress measures to problem gambling. For instance, measures of perceived situational and acute stress have been positively associated with problem gambling (Salerno & Pallanti, 2021; Tang et al., 2019). Chronic sources of stress have also been linked to problem gambling, including homelessness (Vandenberg et al., 2022) trauma (Moore & Grubbs, 2021), the experience of mental health problems (Ronzitti et al., 2018) and stressful life events (Russell et al., 2022). Individuals who experience difficulty in managing affective states also tend to experience more severe problem gambling (Buen & Flack, 2022; Thurm et al., 2023). This is consistent with research that has found associations between the experience of anxiety and depression and problem gambling (Mide et al., 2023; Sundqvist & Wennberg, 2022; Vaughan & Flack, 2022).

While a growing body of research indicates a link between stress and problem gambling, less is known about the psychological processes that may help maintain the stress-problem gambling relationship. One view is that gambling manifests as a way to minimise stress, however, any perceived or actual relief may be short-lived — and may lead to the experience of additional stressors (Buchanan et al., 2020). Chronologically, the stress-problem gambling relationship may develop through the accrual of the negative consequences from gambling, which themselves become a source of stress, which reinforces the need to gamble to escape stress, creating a perpetual cycle (Buchanan et al., 2020; Tseng et al., 2023). However, the assumption that gambling is used to escape heightened levels of stress is often inferred and not explicitly tested. Research that identifies influential and potentially modifiable psychological factors pertaining to problem gambling is of great importance in relation to improving preventative efforts and treatments (Hofmann & Hayes, 2018). Given stress may be considered a precipitating factor in problem gambling, identification of the psychological processes that may help maintain the stress-problem gambling relationship is essential.

Reasons for Gambling: Outcome Expectancies and Coping Style

A common approach to understanding engagement in any given behaviour is to consider the motives or anticipated outcomes of engaging in that behaviour. In relation to gambling, a range of motives and gambling outcome expectancies have been identified, including to win money, experience excitement or mood enhancement, to socialise and to cope with — or escape — stress (Flack & Morris, 2015; Greer et al., 2023; Hagfors et al., 2022). While various gambling specific motives and expectancies are associated with gambling participation, gambling to cope with or escape stress or stressful life events seems especially relevant to problem gambling (Hagfors et al., 2022; Schlagintweit et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2020). For instance, gambling coping motives and escape expectancies have been found to explain variance in problem gambling scores over and above competing reasons for gambling, including the desire to win money (Flack & Morris, 2015; Lelonek-Kuleta & Bartczuk, 2021; Richardson et al., 2023). In fact, a distinct feature that sets gambling apart from the addiction space is that it is probable, however unlikely, that engaging in gambling may alleviate financial stress through winning money (Buchanan et al., 2020). Despite the rich literature around stress and gambling and outcome expectancies and gambling, a relatively under-researched area pertains to how an individual’s perception of gambling as a form of escape relates to their experience of both stress and problem gambling. Potentially, individuals may experience stress and form beliefs that gambling is likely to allow them to escape the stress, leading to problem gambling (Wood & Griffiths, 2007).

An important distinction can also be made between specific gambling motives or outcome expectancies and measures that reflect individuals’ general tendencies to respond to stress. While a diverse range of coping styles and strategies have been proposed shape how people may respond to stress (Stanisławski, 2019), a distinction is commonly made between an adaptive and maladaptive coping style (Solberg et al., 2022). An adaptive coping style involves the use of solution-focused strategies that deal with the stressor. In contrast, a maladaptive coping is typified by avoidance behaviours that are intended to manage the emotional reaction to stress, which may include a range of facets such as disengagement, denial, self-blame, self-distraction, substance use and venting (Meyer, 2001; Solberg et al., 2022).

Despite the heterogeneity in measures, maladaptive coping has been positively associated with a diverse range of addictive behaviours, including problem gambling, where they have been shown to differentiate non-problem gamblers from problem gamblers (Estévez et al., 2021; Jauregui et al., 2017), mediate the relationship between personality characteristics and problem gambling (Pace et al., 2021) and moderate the relationship between gambling involvement and problem gambling (Calado et al., 2017; Dixon et al., 2016). Similar findings are emerging from the e-Sport gaming and gaming disorder literature (e.g. Bányai et al., 2021). While maladaptive coping appears to be implicated in problem gambling, to the authors’ knowledge, research has not directly examined how maladaptive coping style and escape outcome expectancies may converge to influence problem gambling.

The Present Study

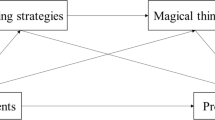

Taken together, escape gambling outcome expectancies and coping styles show promise in explaining the relationship between stress and problem gambling. Based on previous research, it is plausible that escape outcome expectancies may mediate the relationship between stress and problem gambling symptoms. For example, those experiencing heightened level of stress may be more likely to develop favourable views of gambling and, in turn, gamble more excessively (i.e. leading to problem gambling). Also consistent with previous research, coping style may attenuate or intensify these relationships. For instance, the experience of elevated levels of stress and tendency toward a maladaptive coping style may interact to strengthen the stress-expectancies relationship. Put simply, an individual experiencing stress may be more likely to develop escape outcome expectancies, and these may influence problem gambling, especially if the individual engages more maladaptive coping styles. On the other hand, moderation of the escape-problem gambling path would indicate that more maladaptive coping strategies strengthen the association between escape expectancies and problem gambling (i.e. someone forming escape expectancies about gambling would be more likely to engage in problem gambling if they tend to use more maladaptive coping strategies generally). This suggests gamblers who see gambling as a form of escape from stressors could reduce their problem gambling by adopting more adaptive coping styles (Carver & Connor-Smith, 2010). The proposed pathways are depicted in Fig. 1.

If supported, this conceptualisation of the stress-problem gambling association and in particular the proposed moderated mediation paths outline two key targets for intervention. If outcome expectancies account for the link between stress and problem gambling, targeting outcome expectancies through health campaigns or otherwise in individually-focused clinical settings could facilitate behaviour change. Indeed, alcohol expectancy challenge interventions have demonstrated success in terms of reducing alcohol consumption and positive expectancies and increasing negative expectancies in a recent meta-analysis (Gesualdo & Pinquart, 2021). Yi et al. (2015) have similarly proposed a role for expectancy challenges in targeting gambling coping motives in relation to reducing problem gambling. The moderated mediation model aspects of the model indicate potential for synergy in interventions targeting both outcome expectancies and maladaptive coping simultaneously (e.g. by challenging expectancies and teaching more adaptive forms of coping).

The current study examines the relationship between stress, escape outcome expectancies, maladaptive coping and problem gambling, with a sample of participants who gamble more than once a year. The following hypotheses were proposed:

-

1.

Stress will be positively associated with problem gambling.

-

2.

Escape outcome expectancies will be positively associated with stress and problem gambling.

-

3.

Escape outcome expectancies will mediate the relationship between stress and problem gambling.

-

4.

The relationships between stress, escape outcome expectancies and problem gambling will be moderated by maladaptive coping.

Method

Participants and Procedure

An a priori power analysis conducted with MedPower (Kenny, 2017) indicated that a sample size of 205 was required to have 90% power for detecting a small- to medium-mediated effect size (e.g. β = 0.25 for paths a and b), at α = 0.05. Participants (aged 18 years or older) were recruited via an online crowd sourcing service (Microworkers https://www.microworkers.com) and directed to complete online anonymous survey intended to understand people’s reasons for gambling and were paid the equivalent of US$1 for completing the survey. To eliminate potential confounding effects of country-level differences in gambling characteristics, the sampling frame was set to sample Australian residents. Ethics approval was gained to conduct the study via the researchers’ University’s Human Ethics Committee (Ethics approval number: H20099). A total of 240 participants completed the online survey (49.8% of females). The mean age of the sample was 32.76 years (SD = 11.35). Most of the samples were employed (65.0.%), 16.7% unemployed, 15.8% students and 2.5% other or preferred not to say.

Measures

Stress

The stress subscale from the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995) was used to measure current stress. The stress subscale includes 7-items (e.g. “I found it hard to wind down”) measured on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (“Did not apply to me”) to 3 (“Applied to me most of the time”). Research has indicated the reliability of the DASS-21 is comparable when used in non-clinical populations (Sinclair et al., 2012), and invariance testing supports its use across countries (Zanon et al., 2021). The internal consistency of the stress subscale in the present study (i.e. Cronbach’s α) was 0.88.

Problem Gambling

The Problem Gambling Severity Index (Ferris & Wynne, 2001) is a widely used self-report measure of problem gambling within a 12-month period. Participants respond to 9 items (e.g. “Have you felt guilty about the way you gamble or what happens when you gamble?”) using a 4-point rating scale, ranging from 0 (“Never”) to 3 (“Almost always”). Total scores are interpreted using cut-offs, where zero equates to non-problem gambling, a score of 1–4 indicates low risk gambling; 5–7 indicates moderate risk; and 8 or above is indicative of problem gambling; the PGSI total score was used as the outcome variable to test the study’s hypotheses. The scale exhibits acceptable internal consistency (i.e. Cronbach’s α = 0.84) and test re-test reliability (r = 0.78; Ferris & Wynne, 2001). The internal consistency of the PGSI total score in the present study was 0.96.

Escape

Four items from the escape subscale of the Gambling Outcome Expectancies Scale (GOES: Flack & Morris, 2015) were used to address the study’s hypotheses, given noted associations between escape and problem gambling throughout the literature (see Neophytou et al., 2023 for a recent review that compares alternative measures). Responses to items (e.g. “Gambling is a way to forget everyday problems”) are rated on a six-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“Strongly disagree”) to 6 (“Strongly agree”). Previous research has shown the GOES subscales to demonstrate strong reliability (i.e. α > 0.85) and predictive validity (see Flack & Morris, 2016). The internal consistency of the escape subscale for the current study was 0.90.

Maladaptive Coping

The Brief Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced (Brief COPE; Carver, 1997) is a 28-item self-report measure examining a variety of coping mechanisms (e.g. “I’ve been giving up trying to deal with it”), with responses rated on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“I usually don’t do this at all”) to 4 (“I usually do this a lot”). Carver’s (1997) scale is intended to be adapted based on the researchers’ interests. As such, Meyer (2001) used 7 of the 14 facets of the Brief Cope (i.e. behavioural disengagement, denial, self-blame, self-distraction, substance use and venting) to constitute maladaptive coping. Accordingly, scores from these items were summed to reflect a total maladaptive coping score to test the study’s hypotheses. The internal consistency of the maladaptive coping subscale in the present study was 0.88.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Analyses were conducted with IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (IBM Corp, 2021). As indicated by the PGSI (Ferris & Wynne, 2001), 42.9% participants were non-problem gamblers; 10.4% were low-risk gamblers; and 46.7% were in the moderate-risk gamblers to problem gamblers’ range. Univariate screening and Pearson product-moment correlations indicate the data are suitable to proceed with testing the moderated-mediation model outlined in Fig. 1. Specifically, the data were free from univariate outliers and not substantially skewed (all absolute scores falling below 1), and correlations between the variables of interest indicated a suitable pattern of relationships to perform the moderated-mediation analysis (i.e. stress, escape and PGSI scores were positively associated). No significant associations were observed between gender and escape or gender and problem gambling severity. Age was significantly correlated with escape outcome expectancies and problem gambling severity.

The moderated mediation model was tested using Hayes’ (2018) PROCESS macro. The mediation path modelled the effect of X (stress) on Y (PGSI score) via the M (escape) and W (maladaptive coping), including age as a covariate. Variables were mean centred to minimise multicollinearity, and the quantity of bootstrap samples used to determine 95% confidence intervals (CI) was set at 5000. Pre-screening of the variables revealed no concerns with multicollinearity (minimum tolerance = 0.57) and the variance inflation factor (VIF) for all variables were all below the critical value of 10 (maximum value = 1.74). The data were free from multivariate outliers (i.e. the Mahalanobis distance value of 15.82 did not exceed the critical value of 18.47, df = 4, α = 0.001); similarly, the maximum Cook’s Distance value was 0.20 (i.e. not exceeding 1) indicating that none of the cases had an undue influence on the model.

Table 1 shows inter-correlations, means and standard deviations of the variables of interest.

Moderated Mediation Model

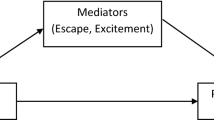

There was partial support for the moderated-mediation model, where the analysis revealed the relationship between stress and escape outcome expectancies changed as a function of the level of maladaptive coping; β = 0.02; CI (0.01, 0.04). However, the relationship between escape outcome expectancies and problem gambling did not vary as a function maladaptive coping; β = 0.01; CI (< − 0.01, 0.02). That is, the relationship between stress and escape outcome expectancies increased as maladaptive coping increased.Footnote 1 Contrary to expectations, the strength of the relationship between escape outcome expectancies and problem gambling was not contingent on maladaptive coping. The moderated mediation model with the unstandardised parameter estimates is shown in Fig. 2.

To further examine the role of significant moderated mediation effect, the relationship between stress and escape outcome expectancies was tested at the 16th, 50th and 84th percentiles of maladaptive coping, revealing that the relationship between stress and escape was non-significant when maladaptive coping was low: β = − 0.14; 95% CI (− 0.34, 0.07) or moderate: β = 0.09; 95% CI (− 0.07, 0.25). However, there was a significant positive relationship between stress and escape when maladaptive coping was rated high, β = 0.27; 95% CI (0.06, 0.48). The statistics for the moderated mediation model are displayed in Table 2. Figure 3 shows the relationship between stress and escape outcome expectancies for each level of the conditional effects of maladaptive coping, with the conditional effects reported in Table 3.

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to further elucidate the stress-problem gambling link by incorporating escape gambling outcome expectancies and coping style. Specifically, escape outcome expectancies were hypothesised to mediate the relationship between stress and problem gambling, and this pathway was considered dependent on the extent to which an individual engages in maladaptive coping. The results indicated support for the mediation effect (i.e. escape expectancies explain the process by which stress leads to problem gambling) and partial support for moderated mediation — specifically, that the relationship between stress and escape expectancies strengthened when maladaptive coping was high, but when low or moderate, the relationship was not significant. This finding indicates outcome expectancies are not only a potential mechanism through which the stress-problem gambling relationship may operate specifically, but that this relationship depends on whether or not gamblers are engaging in maladaptive coping generally. While gambling researchers have explored maladaptive coping mechanisms as a potential means of explaining problem gambling (Calado et al., 2017; Jauregui et al., 2017; Pace et al., 2021), to our knowledge, this is the first study to establish maladaptive coping as a moderator of the relationship between stress and escape outcome expectancies, in relation to the effect of escape expectancies on problem gambling severity.

Recent revisions to the gambler pathways model illustrates developmental (i.e. emotional vulnerability) and contextual (i.e. coping motivation) pathways to problem gambling, that implicate ecological, cognitive and behavioural elements of gambling (Nower et al., 2022). The current study’s findings highlight the importance of pursuing tailored interventions for gambling interventions where coping styles and escape outcome expectancies may be influential. These factors are especially important in the context of relapse prevention for problem gambling and addictive behaviours more generally. For instance, recent research by Dowling et al. (2021) used ecological momentary assessment to ascertain the nature of how phasic (i.e. proximal risk factors) and tonic precipitants of gambling (i.e. chronic vulnerabilities) interact in relation to problem gambling. While Dowling et al. did not use the maladaptive subscale of the COPE in their analyses, they argue that outcome expectancies acted as phasic determinants that interact with other phasic and tonic processes in relation to problem gambling. Indeed, a current focus of problem gambling treatment is just-in-time adaptive interventions (JITAIs) that provide the right support at the right time in relation to an individuals’ experienced vulnerabilities (Dowling et al., 2023). The present findings indicate that these interventions may be enhanced by considering stress reduction and/or implementing adaptive coping strategies in problem gambling contexts where these associations are relevant.

Given the findings illustrate an important role for escape outcome expectancies, it is important to consider how findings from the outcome expectancy literature may be used in the context of behavioural addictions such as problem gambling. In the wealth of literature on alcohol expectancies, positive outcome expectancies have been found to moderate the association between measures of anxiety and drinking behaviour (Kushner et al., 1994). More recent research has demonstrated the association between negative urgency (i.e. spontaneous action intended to escape emotional distress stemming from negative moods) and alcohol consumption behaviour is mediated by positive outcome expectancies (Anthenien et al., 2017). Indeed, expectancy challenge interventions have demonstrated utility in the alcohol consumption space (Scott-Sheldon et al., 2012), and it may be useful to pursue whether or not gambling-related outcome expectancies can be challenged in a similar way, and if these challenges lend to reductions in problem gambling. In a typical expectancy challenge scenario, participants who hold positive social alcohol expectancies (e.g. that alcohol makes people more outgoing) are shown how these effects vary between individuals, and informed of the depressant effects of alcohol, such as impaired coordination (Larimer et al., 2022). In a gambling context, a plausible attempt to challenge expectancies could constitute providing information on the risk of experiencing a range of harms from gambling over time to individuals who hold positive escape expectancies about gambling. For example, Sleczka and Romild (2021) have shown that higher scores on the tolerance items of the PGSI nearly triple a person’s risk of experiencing more severe gambling problems a year later. Given the tolerance item reflects needing to gamble more to experience the same feelings, the more stress an individual experiences (including gambling stress), the more they may gamble to alleviate that stress — which increases their risk of problem gambling. Reappraisal (which could be considered an intended outcome of an expectancy challenge attempt) has been considered more broadly in relation to problem gambling; however, mixed effects have been observed throughout the literature (Neophytou et al., 2023). Challenging gambling-related escape expectancies experimentally may therefore present a more promising route for enhancing the efficacy of reappraisal-based interventions.

Of course, at the most distal, the link between stress and problem gambling can be attenuated by targeting stress itself by facilitating more adaptive coping styles or targeting stress-reduction skills among problem gamblers. For instance, CBT interventions have been shown to be effective in treating problem gambling, although the available literature shows considerable heterogeneity (Pfund et al., 2023). There may be elements of cognitive behavioural formulation that work especially well in targeting maladaptive coping among gamblers or escape expectancies themselves or offer broad therapeutic benefit in relation to comorbid mental disorders (Vaughan and Flack, 2022). Imaginal desensitisation, mindfulness approaches and engagement in alternative leisure activities have also shown promise in relation to addressing problem gambling (Grant et al., 2011; Samuelsson et al., 2018; Sancho et al., 2018).

Limitations and Future Research Directions

The study provides important preliminary evidence that shows a plausible process by which stress leads to problem gambling. However, these findings warrant consideration of the study’s limitations. Firstly, while a substantial sample was used, the data were cross-sectional, and causal links between the component variables could not be tested. Future research should look at longitudinal support for the moderated mediation pathway, especially given stressors can vary over time, and with increased engagement in gambling. Secondly, the sample primarily consisted of no-risk gamblers (52.6%). Although gambling harm is commonly considered from the population level, further research should seek to test the moderated mediation pathways in gambling disordered populations. Thirdly, the use of self-report measures means individuals may have underreported their gambling problems (e.g. due to social desirability bias) or were biased in their recall.

Though the moderated mediation results are informative, it may be pertinent to explore whether other variables are useful in explaining the association between stress and problem gambling. While not the focus of the present study, emotional regulation has been found to mediate the relationship between stress and problem gambling (Tang et al., 2019) and is predictive of gambling-related cognitive biases (Buen & Flack, 2022; Estévez et al., 2021). It will be important to determine the relative influence of emotional regulation and maladaptive coping and their temporal relationships with problem gambling (Emond et al., 2022; Marchica et al., 2019). This may be especially pertinent to mental disorders experienced by problem gamblers, where maladaptive coping is largely implicated (Moritz et al., 2016). Path analytic and mixture modelling approaches may be helpful in delineating the role of emotion regulation, coping styles and beliefs and more comprehensively accounting for the relationship between stress and problem gambling. Such research can more adequately inform effective gambling interventions in specific population contexts (e.g. Eriksen et al., 2023), as well as improve the effectiveness of population-level problem gambling public health messaging (Lole et al., 2019), to prevent problem gambling or reduce its prevalence.

Conclusion

The present research provided further insights into the stress-problem gambling relationship, indicating that both escape outcome expectancies and maladaptive coping are implicated in problem gambling. The findings indicate a need to further investigate whether outcome expectancy challenges within the gambling context may have utility in informing gambling interventions, when combined with methods to reduce maladaptive coping or develop more adaptive coping strategies or mitigating stress responses.

Data Accessibility

Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Notes

We thank an anonymous reviewer for their suggestion to rerun the analyses excluding the two self-distraction items from the Brief COPE; the results of these analyses were consistent, and are available from the corresponding author on request.

References

Anthenien, A. M., Lembo, J., & Neighbors, C. (2017). Drinking motives and alcohol outcome expectancies as mediators of the association between negative urgency and alcohol consumption. Addictive Behaviors, 66, 101–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.11.009

Bányai, F., Zsila, Á., Kökönyei, G., Griffiths, M. D., Demetrovics, Z., & Király, O. (2021). The moderating role of coping mechanisms and being an e-sport player between psychiatric symptoms and gaming disorder: Online survey. JMIR Ment Health, 8(3), e21115. https://doi.org/10.2196/21115

Buchanan, T. W., McMullin, S. D., Baxley, C., & Weinstock, J. (2020). Stress and gambling. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 31, 8–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2019.09.004

Buen, A., & Flack, M. (2022). Predicting problem gambling severity: Interplay between emotion dysregulation and gambling-related cognitions. Journal of Gambling Studies, 38(2), 483–498. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-021-10039-w

Calado, F., Alexandre, J., & Griffiths, M. D. (2017). How coping styles, cognitive distortions, and attachment predict problem gambling among adolescents and young adults. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6(4), 648–657. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.6.2017.068

Carver, C. S. (1997). You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: Consider the Brief COPE. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 4(1), 92–100. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6

Carver, C. S., & Connor-Smith, J. (2010). Personality and coping. Annual Review of Psychology, 61(1), 679–704. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100352

Dixon, R. W., Youssef, G. J., Hasking, P., Yücel, M., Jackson, A. C., & Dowling, N. A. (2016). The relationship between gambling attitudes, involvement, and problems in adolescence: Examining the moderating role of coping strategies and parenting styles. Addictive Behaviors, 58, 42–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.02.011

Dowling, N. A., Merkouris, S. S., & Spence, K. (2021). Ecological momentary assessment of the relationship between positive outcome expectancies and gambling behaviour. Journal of Clinical Medicine 10(8), 1709. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10081709

Dowling, N. A., Rodda, S. N., & Merkouris, S. S. (2023). Applying the Just-In-Time Adaptive Intervention Framework to the development of gambling interventions. Journal of Gambling Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-023-10250-x

Emond, A., Griffiths, M. D., & Hollén, L. (2022). Problem gambling in early adulthood: A population-based study. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 20(2), 754–770. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00401-1

Eriksen, J. W., Fiskaali, A., Zachariae, R., Wellnitz, K. B., Oernboel, E., Stenbro, A. W., Marcussen, T., & Petersen, M. W. (2023). Psychological intervention for gambling disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 12(3), 613–630. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2023.00034

Estévez, A., Jauregui, P., Lopez-Gonzalez, H., Mena-Moreno, T., Lozano-Madrid, M., Macia, L., ... & Jimenez-Murcia, S. (2021). The severity of gambling and gambling related cognitions as predictors of emotional regulation and coping strategies in adolescents. Journal of Gambling Studies 37(2), 483–495. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-020-09953-2

Ferris, J., & Wynne, H. (2001). The Canadian problem gambling index: Final report. Retrieved October 12, 2023, from https://www.greo.ca/

Flack, M., & Morris, M. (2015). Problem gambling: One for the money…? Journal of Gambling Studies, 31(4), 1561–1578. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-014-9484-z

Flack, M., & Morris, M. (2016). The temporal stability and predictive ability of the Gambling Outcome Expectancies Scale (GOES): A prospective study. Journal of Gambling Studies, 32(3), 923–933. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-015-9581-7

Gesualdo, C., & Pinquart, M. (2021). Expectancy challenge interventions to reduce alcohol consumption among high school and college students: A meta-analysis. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 35(7), 817–828. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000732

Grant, J. E., Donahue, C. B., Odlaug, B. L., & Kim, S. W. (2011). A 6-month follow-up of imaginal desensitization plus motivational interviewing in the treatment of pathological gambling. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry, 23(1), 3–10.

Greer, N., Hing, N., Rockloff, M., Browne, M., & King, D. L. (2023). Motivations for esports betting and skin gambling and their association with gambling frequency, problems, and harm. Journal of Gambling Studies, 39(1), 339–362. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-022-10137-3

Hagfors, H., Castrén, S., & Salonen, A. H. (2022). How gambling motives are associated with socio-demographics and gambling behavior - A Finnish population study. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 11(1), 63–74. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2022.00003

Hayes, A. F. (2018). An introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Hofmann, S. G., & Hayes, S. C. (2018). The future of intervention science: Process-based therapy. Clinical Psychological Science, 7(1), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702618772296

IBM Corp. (2021). IBM SPSS Statistics for windows, version 28.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp

Jauregui, P., Onaindia, J., & Estévez, A. (2017). Adaptive and maladaptive coping strategies in adult pathological gamblers and their mediating role with anxious-depressive symptomatology. Journal of Gambling Studies, 33(4), 1081–1097. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-017-9675-5

Kenny, D. A. (2017, February). MedPower: An interactive tool for the estimation of power in tests of mediation [Computer software]. Retrieved February 26, 2023, from https://davidakenny.shinyapps.io/MedPower/

Kushner, M. G., Sher, K. J., Wood, M. D., & Wood, P. K. (1994). Anxiety and drinking behavior: Moderating effects of tension-reduction alcohol outcome expectancies. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 18(4), 852–860. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.1994.tb00050.x

Larimer, M. E., Kilmer, J. R., Cronce, J. M., Hultgren, B. A., Gilson, M. S., & Lee, C. M. (2022). Thirty years of BASICS: Dissemination and implementation progress and challenges. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 36(6), 664–677. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000794

Lelonek-Kuleta, B., & Bartczuk, R. P. (2021). Online gambling activity, pay-to-win payments, motivation to gamble and coping strategies as predictors of gambling disorder among e-sports bettors. Journal of Gambling Studies, 37(4), 1079–1098. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-021-10015-4

Lole, L., Li, E., Russell, A. M., Greer, N., Thorne, H., & Hing, N. (2019). Are sports bettors looking at responsible gambling messages? An eye-tracking study on wagering advertisements. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 8(3), 499–507. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.8.2019.37

Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U

Marchica, L. A., Mills, D. J., Keough, M. T., Montreuil, T. C., & Derevensky, J. L. (2019). Emotion regulation in emerging adult gamblers and its mediating role with depressive symptomology. Journal of Affective Disorders, 258, 74–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.07.078

Meyer, B. (2001). Coping with severe mental illness: Relations of the Brief COPE with symptoms, functioning, and well-being. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 23(4), 265–277. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1012731520781

Mide, M., Arvidson, E., & Gordh, A. S. (2023). Clinical differences of mild, moderate, and severe gambling disorder in a sample of treatment seeking pathological gamblers in Sweden. Journal of Gambling Studies, 39(3), 1129–1153. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-022-10183-x

Moore, L. H., & Grubbs, J. B. (2021). Gambling disorder and comorbid PTSD: A systematic review of empirical research. Addictive Behaviors, 114, 106713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106713

Moritz, S., Jahns, A. K., Schröder, J., Berger, T., Lincoln, T. M., Klein, J. P., & Göritz, A. S. (2016). More adaptive versus less maladaptive coping: What is more predictive of symptom severity? Development of a new scale to investigate coping profiles across different psychopathological syndromes. Journal of Affective Disorders, 191, 300–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.11.027

Neophytou, K., Theodorou, M., Artemi, T.-F., Theodorou, C., & Panayiotou, G. (2023). Gambling to escape: A systematic review of the relationship between avoidant emotion regulation/coping strategies and gambling severity. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 27, 126–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2023.01.004

Nower, L., Blaszczynski, A., & Anthony, W. L. (2022). Clarifying gambling subtypes: The revised pathways model of problem gambling. Addiction, 117(7), 2000–2008. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15745

Pace, U., D’Urso, G., Ruggieri, S., Schimmenti, A., & Passanisi, A. (2021). The role of narcissism, hyper-competitiveness and maladaptive coping strategies on male adolescent regular gamblers: Two mediation models. Journal of Gambling Studies, 37(2), 571–582. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-020-09980-z

Pfund, R. A., Forman, D. P., Whalen, S. K., Zech, J. M., Ginley, M. K., Peter, S. C., McAfee, N. W., & Whelan, J. P. (2023). Effect of cognitive-behavioral techniques for problem gambling and gambling disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction, 118(9), 1661–1674. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.16221

Richardson, A. C., Flack, M., & Caudwell, K. M. (2023). Two for the GOES: Exploring gambling outcome expectancies scores across mixed and offline-only gamblers in relation to problem gambling risk status. Journal of Gambling Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-023-10234-x

Ronzitti, S., Kraus, S. W., Hoff, R. A., & Potenza, M. N. (2018). Stress moderates the relationships between problem-gambling severity and specific psychopathologies. Psychiatry Research, 259, 254–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.10.028

Russell, A. M. T., Browne, M., Hing, N., Visintin, T., Begg, S., Rawat, V., & Rockloff, M. (2022). Stressful life events precede gambling problems, and continued gambling problems exacerbate stressful life events: A life course calendar study. Journal of Gambling Studies, 38(4), 1405–1430. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-021-10090-7

Salerno, L., & Pallanti, S. (2021). COVID-19 related distress in gambling disorder. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.620661

Samuelsson, E., Sundqvist, K., & Binde, P. (2018). Configurations of gambling change and harm: Qualitative findings from the Swedish longitudinal gambling study (Swelogs). Addiction Research & Theory, 26(6), 514–524. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066359.2018.1448390

Sancho, M., De Gracia, M., Rodriguez, R. C., Mallorquí-Bagué, N., Sánchez-González, J., Trujols, J., ... & Menchon, J. M. (2018). Mindfulness-based interventions for the treatment of substance and behavioral addictions: a systematic review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00095

Schlagintweit, H. E., Thompson, K., Goldstein, A. L., & Stewart, S. H. (2017). An investigation of the association between shame and problem gambling: The mediating role of maladaptive coping motives. Journal of Gambling Studies, 33(4), 1067–1079. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-017-9674-6

Scott-Sheldon, L. A. J., Terry, D. L., Carey, K. B., Garey, L., & Carey, M. P. (2012). Efficacy of expectancy challenge interventions to reduce college student drinking: A meta-analytic review. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 26(3), 393–405. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027565

Sinclair, S. J., Siefert, C. J., Slavin-Mulford, J. M., Stein, M. B., Renna, M., & Blais, M. A. (2012). Psychometric evaluation and normative data for the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scales-21 (DASS-21) in a nonclinical sample of US adults. Evaluation & the Health Professions, 35(3), 259–279. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163278711424282

Sleczka, P., & Romild, U. (2021). On the stability and the progression of gambling problems: Longitudinal relations between different problems related to gambling. Addiction, 116(1), 116–125. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15093

Solberg, M. A., Gridley, M. K., & Peters, R. M. (2022). The factor structure of the brief cope: A systematic review. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 44(6), 612–627. https://doi.org/10.1177/01939459211012044

Stanisławski, K. (2019). The coping circumplex model: An integrative model of the structure of coping with stress. Frontiers in Psychology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00694

Sundqvist, K., & Wennberg, P. (2022). Problem gambling and anxiety disorders in the general Swedish population – A case control study. Journal of Gambling Studies, 38(4), 1257–1268. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-022-10117-7

Tang, C.S.-K., Lim, M. S. M., Koh, J. M., & Cheung, F. Y. L. (2019). Emotion dysregulation mediating associations among work stress, burnout, and problem gambling: A serial multiple mediation model. Journal of Gambling Studies, 35(3), 813–828. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-019-09837-0

Thurm, A., Satel, J., Montag, C., Griffiths, M. D., & Pontes, H. M. (2023). The relationship between gambling disorder, stressful life events, gambling-related cognitive distortions, difficulty in emotion regulation, and self-control. Journal of Gambling Studies, 39(1), 87–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-022-10151-5

Tseng, C. H., Flack, M., Caudwell, K. M., & Stevens, M. (2023). Separating problem gambling behaviors and negative consequences: Examining the factor structure of the PGSI. Addictive Behaviors, 136, 107496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2022.107496

Vandenberg, B., Livingstone, C., Carter, A., & O’Brien, K. (2022). Gambling and homelessness: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence. Addictive Behaviors, 125, 107151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.107151

Vaughan, E., & Flack, M. (2022). Depression symptoms, problem gambling and the role of escape and excitement gambling outcome expectancies. Journal of Gambling Studies, 38(1), 265–278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-021-10032-3

Wang, C., Cunningham-Erdogdu, P., Steers, M.-L.N., Weinstein, A. P., & Neighbors, C. (2020). Stressful life events and gambling: The roles of coping and impulsivity among college students. Addictive Behaviors, 107, 106386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106386

Wood, R. T. A., & Griffiths, M. D. (2007). A qualitative investigation of problem gambling as an escape-based coping strategy. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 80(1), 107–125. https://doi.org/10.1348/147608306X107881

Yi, S., Stewart, M., Collins, P., & Stewart, S. H. (2015). The activation of reward versus relief gambling outcome expectancies in regular gamblers: Relations to gambling motives. Journal of Gambling Studies, 31(4), 1515–1530. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-014-9474-1

Zanon, C., Brenner, R. E., Baptista, M. N., Vogel, D. L., Rubin, M., Al-Darmaki, F. R., Gonçalves, M., Heath, P. J., Liao, H.-Y., Mackenzie, C. S., Topkaya, N., Wade, N. G., & Zlati, A. (2021). Examining the dimensionality, reliability, and invariance of the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale–21 (DASS-21) across eight countries. Assessment, 28(6), 1531–1544. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191119887449

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ivana Bacovic: conceptualization, methodology, preliminary analysis and writing — original draft preparation. Kim Caudwell and Mal Flack: conceptualization, methodology, analysis, writing — review and editing and supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

All the procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the research team’s organizational Ethics Board and with the 1975 Helsinki Declaration, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Caudwell, K.M., Bacovic, I. & Flack, M. What Role Do Maladaptive Coping and Escape Expectancies Play in the Relationship Between Stress and Problem Gambling? Testing a Moderated Mediation Model. Int J Ment Health Addiction (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-023-01238-0

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-023-01238-0