Abstract

This paper offers a comprehensive and updated review of the effects of intergovernmental grants. We focus on the main findings in the existing literature on the effects of intergovernmental grants on tax policy and choices, expenditure decisions, fiscal stability and behavioral choices, and political economy. The intricate nature of the subject, intrinsically, does not allow for an all-inclusive survey, but we aim to provide a thorough examination and update of the most salient effects of intergovernmental grants, while indicating areas for further research.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Intergovernmental grants are a key financial instrument for funding subnational governments, at both the local and intermediate or regional levels, serving different objectives.Footnote 1 Oates (1990) identifies a threefold rationality for intergovernmental transfers to subnational jurisdictions. First, for financing subnational public services and investments: Upper tiers of government may provide intergovernmental grants with lower tiers to increase their capacity to provide services, filling the vertical fiscal gap left between diverging tax and expenditure decentralization levels. Second, subsidization: When the provision of services involves spillovers or externalities, central government may subsidize those services which are in risk of not being optimally provided, boosting subnational government spending in priority areas for the whole country and addressing inter-jurisdictional externalities. Third, equalization: Central governments may try to enable subnational governments with different fiscal capacity and expenditure needs to provide the same or equivalent public services with roughly a similar level of subnational tax effort, following redistributive and solidarity motivations.

Over the past several decades, a large body of literature has contributed to our understanding of whether and to what extent the several targets of intergovernmental transfers are met, and how complex the responses of subnational governments can be, largely depending on how grants are designed and implemented. Literature surveys on this topic include Gramlich (1977), Hines and Thaler (1995), Bailey and Connolly (1998), Oates (1998), Gamkhar and Shah (2007), Inman (2008), Boadway and Shah (2009); Yilmaz and Zahir (2020), and Clemens and Veuger (2023). Focusing on the most recent surveys, Yilmaz and Zahir (2020) make significant contributions through their empirical, theoretical, and methodological research, along with insightful case studies. Their work sheds light on how various countries deviate from the fundamental principles of needs, equity, and efficiency when it comes to resource sharing. For their part, Clemens and Veuger (2023) revise some of the canonical papers on the role of intergovernmental grants in fiscal federalism systems, as well as the recent impact of transfers on state-level corporate tax policy in the COVID-19 framework. Our paper provides an update of this literature by offering a comprehensive review of what is known to date on the main effects, both pursued and unintended, of intergovernmental grants. By doing so, we aim to contribute to the understanding of the still conflicting views about the design and effects of intergovernmental grants, as pointed out by Yilmaz and Zahir (2020). Additionally, we particularly focus on the empirical identification strategies followed and on which direction research should go to keep improving the robustness of the results obtained.

In addition, we go beyond the intended effects of grants in vertical and horizontal imbalances or specific policy objectives, to also focus on how intergovernmental grants can alter subnational budget constraints, incentive systems and the institutional settings framing intergovernmental relations. The policy implications of our review are significant because subnational government responses and the consequences on the efficiency and equity of fiscally decentralized systems are often far reaching. With this information, policy makers can become much more aware of what the potential indirect effects of grant design may be and therefore try to avoid shortcomings and unplanned troubles.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: In Sect. 2, we introduce a nomenclature for the different main types of grants we may observe, providing a common vocabulary to the often-diverse terminology employed in the empirical works surveyed in the rest of the paper. In Sect. 3, we critically review findings on the main different impacts of intergovernmental grants on tax policy choices, including the impacts on tax effort and tax competition, the impact of grants on expenditure decisions by subnational governments, with especial emphasis on the phenomenon of the “fly-paper effect”, and the presence of possible asymmetric responses both in terms of tax and spending choices. In Sect. 4, we analyze the effects on fiscal stability and fiscal policy. In Sect. 5, we analyze the impact of intergovernmental grants on political institutions, including accountability and subnational autonomy. Section 6 concludes. At the end of every section, a table that summarizes the main findings of the specific literature is referenced. Papers are selected according to its perceived relevance from both a subjective criterion and its impact measured by Google Scholar. They are ordered in tables following a chronological structure. The information displayed includes the definition of the main outcome variables and type of grants analyzed, the data sample and the empirical strategy and a brief review of the results.

2 On the taxonomy and theoretical effects of grants

2.1 Classification

Intergovernmental grants can be classified according to their purpose and to how funds are allocated. Regarding the first dimension, the literature has mainly divided intergovernmental grants into conditional (also called earmarked, categorical, or specific-purpose grants) and unconditional grants (also called general-purpose grants).Footnote 2 Conditional grants restrict the receiving government to specific forms of spending. In contrast, unconditional grants have no restriction on what the funds can be spent on.

Subnational governments face a behavioral response when there is a change in transfers, encompassing both income and substitution effects. The substitution or price effect captures the impact of variations in grants on the cost of the subsidized public spending, whereas the income effect reflects how transfers influence the overall resources available to the subnational government. Consequently, each type of transfer has the potential to trigger one or both effects.

Economic theory suggests that unconditional grants induce a pure income effect and thus affect the local government public goods expenditure according to the median voter’s marginal propensity to spend on local public goods (Hines & Thaler, 1995). The estimates of this income effect may range from 15 to 20% for most countries depending on the degree of conditionality of grants (Lundqvist, 2015).

Both conditional and (much less frequently) unconditional grants may be themselves categorized in matching and non-matching grants, depending on the requirement that subnational governments contribute or not a share of the funds. Conditional matching grants require subnational governments to contribute their own resources toward financing certain types of expenditures, thereby reducing their relative cost and involving a substitution effect. Furthermore, an income effect arises as the jurisdiction ends up with additional resources that can be allocated to further increase the consumption of all public goods (Arvate et al. 2017). Conversely, unconditional grants only have an income effect. The reason why is that since these types of grants can be allocated to any combination of public goods or services with the relative prices remaining unaffected (Boadway & Shah, 2009; Shah, 2007).Footnote 3

Conditional grants may also be differentiated by the timing of the conditionality: ex ante, the most common practice, or ex post, as in the case of performance-based transfers.Footnote 4 The difference is that the latter links the performance of subnational governments to the access and/or the amount of funding, thus improving the chances of more effective service delivery (Martínez-Vázquez, 2020). Furthermore, grants can be differentiated according to whether their allocation is formula-based (based on pre-defined criteria) or discretionary (allocated on an ad hoc manner).Footnote 5

2.2 Is there a best type of grant and optimal design?

The First-Generation Theory of Fiscal Federalism (FGT) advocates for the devolution of spending responsibilities to subnational governments, aiming to achieve efficiency and equity within a decentralized system. These theories highlight the crucial role of intergovernmental grants in addressing horizontal and vertical imbalances, an also as a mechanism to internalize spillovers beyond regional borders (Martínez-Vazquez et al., 2017). The FGT is normative in nature, assuming that both the central and subnational decision-makers behave in a benevolent manner, seeking to maximize social welfare (Chandra Jha, 2015; Oates, 2005; Weingast, 2014; Yilmaz & Zahir, 2020).

On the other hand, the Second-Generation Theory (SGT) argues that public decision-makers are influenced and constrained by political institutions and may have their own agenda, which may diverge from maximizing citizen’s welfare. This literature portrays a world where imperfect information and selfish objective functions of political agents shape political and fiscal institutions (Oates, 2005). The SGT emphasizes the important role of grants on regional incentives to promote subnational tax collection for local development, and for addressing rent-seeking and budget balance issues (Bird & Vaillancourt, 1999; Chandra Jha, 2015; Martínez-Vazquez et al., 2017; Yilmaz & Zahir, 2020). SGT has significant implications for the design of intergovernmental transfers to achieve equalization goals without interfering with subnational actors’ incentives.

While FGT and SGT often align on various core aspects, they can occasionally diverge in their predictions regarding the consequences of intergovernmental grants and the underlying mechanisms that drive those outcomes (Martínez-Vazquez et al., 2017). Nevertheless, the FGT has faced criticism for its inability to account for the numerous perverse incentives associated with intergovernmental grants and the diverse preferences held by various stakeholders. Complementary, SGT particularly focus on the potential distortionary effect of transfers on local economic development (Yilmaz & Zahir, 2020).

Two fundamental questions in the theory and practice of transfer design are first, whether some types of transfers are superior instruments to others, and second, what may be the optimal design of those instruments. Regarding the first question, there have been discussions in the literature, for example, comparing unconditional to conditional grants, and among the latter whether block grants may be superior instruments to specific grants. However, there is no such a thing as a “best type of grant”. Practically all types of grants can be the most preferred depending on the situation and context. There is a large array of worthwhile objectives that different grants help support, and the art of transfer design is to reach a balance between them.

Unconditional grants, such as revenue sharing or equalization transfers, may be superior to reduce of vertical and horizontal imbalances because they also allow complete spending autonomy to subnational governments. However, conditional grants, such as block and specific grants, can be better instruments when some specific objective of the transfer needs to be achieved and subnational governments are wanted to perform some work or service to that end. For instance, conditional transfers are largely used to subsidize programs deemed essential by the decision-maker, or they are also employed to fund programs that generate high levels of externalities (Boadway & Shah, 2007). And while block grants impose a softer type of conditionality than specific grants, thus allowing more autonomy to subnational governments, specific grants may sometimes be preferred because of the need to ensure certain outcomes, e.g., child vaccination programs, or to avoid “blaming game dynamics” between the central and subnational governments (Borge & Lilleschulstad, 2009; Searle & Martinez-Vazquez, 2007).

Thus, a clear definition of an objective and the demonstrated ability of a particular transfer instrument to achieve that objective is what determines the superiority of that instrument. A common mistake in the practice of grant design across countries is to design intergovernmental grants in the simultaneous pursuit of multiple objectives within a single instrument. Lack of transparency, confusion on the outcomes being achieved, and even inefficiencies may easily arise in that context. In practice, each country has its own history regarding the evolving structure of the intergovernmental grant system. More mature and evolved decentralized systems tend to rely more on unconditional than on conditional grants; when the latter are used, they are more likely to be block grants than specific earmarked grants in reaction to the historical overuse of a multiplicity of specific grants.Footnote 6

Regarding the optimality of design question, there is general agreement on the general principles, such as simplicity, efficiency, equity, or revenue adequacy, that transfer design should meet (Boadway & Shah, 2007; Martinez-Vazquez & Searle, 2006). But beyond those general principles, even though it has been extensively analyzed, it has been hard to reach a consensus on what the optimal design of the different transfer instruments should be.Footnote 7 And the causes are multiple. Taking the salient example of equalization grants, redistributive objectives necessarily entail subjective perceptions and judgments, over which even fully rational agents can disagree (Boadway, 2006).Footnote 8 For many other transfer instruments, as Boadway (2006) also argues, it is difficult to understand or fully predict the behavior of the subnational governments themselves. In addition, the extent of fiscal decentralization is itself a relevant determinant for the need and also the design features of transfers (Boadway & Shah, 2007; Yilmaz & Zahir, 2020).

In the past, many countries made extensive use of ad hoc transfers. However, for some time now many governments have shifted away from ad hoc transfer negotiations and have adopted formula-based and derivation-principle approaches to the allocation of transfer. This transition has aimed to addressing issues related to rent-seeking behavior and inefficiencies in local service provision, as highlighted by Bahl (2000) and Yilmaz and Zahir (2020). Further trends in design include lesser use of conditionality and matching provisions in grants, as, for example, documented for the USA by Kattenberg and Vermeulen (2018).

Drawing many robust conclusions is also difficult by the fact that the empirical literature on the impact of transfer design is characterized by a large heterogeneity in countries or groups of countries covered, time frame periods, estimation techniques and variables, and specific goals analyzed, making many of the results not directly comparable. Consequently, the desirable transfer instrument design tends to be highly dependent on the priority objectives and specific contextual factors of a particular country.

3 Effects on tax and expenditure choices

The theory of fiscal federalism has always emphasized the key importance of subnational revenue autonomy. This latter yields a large variety of benefits ranging from greater accountability to greater spending efficiency and fiscal responsibility. Transfers are seen as the main financing alternative to own revenues, and even though they can be perfectly justified, their effects on how subnational revenue autonomy is utilized can be widespread and pervasive. However, it is evident that intergovernmental transfers not only affect subnational own revenues but also their spending and budget balance behavior. The public budget constraint tightly relates spending, taxes, grants, and borrowing. Hence, changes in the amount of grants involve potential adjustments in the remaining components of the budget constraint to hold the basic identity between total spending and total revenues.

Our discussion starts with the effects that transfers directly or indirectly may have on the behavior and decision making of subnational governments regarding their tax policy decisions. Based on both their relevance and the attention that have attracted in the literature, we discuss the effects of transfers on subnational tax effort, with the generation of both crowding-out and crowding-in effects; their effects on tax competition among subnational governments; and the existence of asymmetric responses of subnational governments, depending on the sign of changes in the level of intergovernmental transfers. Next, we examine the effects on the expenditure side of the budget. In particular, we focus on research studying the impact of transfers on the overall size of the public sector and on the so-called fly-paper effect. This latter addresses the common observation that transfers appear to have a significantly larger effect on subnational spending than equivalent size increases in the private income of the jurisdiction’ residents.

3.1 Tax effort and crowding-out effects

The impact of grants on taxes collected by subnational governments has been a main focus of the literature.Footnote 9 Many scholars have argued that grants induce a crowding-out effect because of the negative incentives generated for subnational governments to raise their own revenues. The basic mechanism for this crowding-out effect is based on political economy arguments. Subnational government officials find it less politically costly to depend on transfers than on asking their voters to pay more taxes, while their central governments may oblige them because that transfer dependence gives them a sense of power and control. Theoretical work that attempts to explain the crowding-out effect of transfers on own subnational revenues includes research by Bradford and Oates (1971a, 1971b), Abdullatif (2006) and Mogues and Benin (2012).

However, results vary depending on how grants are designed. For example, as we discussed further below equalization grants may be defined to provide lower amounts to those jurisdictions that collect more by exerting a higher tax effort. The choice of transfer instrument can also contribute to the level of crowding out. For example, block general grants are more subject to negotiation and bargaining between government tiers than is the case with specific grants. And it is logical to expect that conditional grants may have a smaller stimulating impact on subnational tax choices compared to unconditional transfers given the different degrees of flexibility in the use of the funds (Brun & El Khdari, 2016). As we will see in later sections that design choices are also important on a variety of other effects considered, from the fly paper to externalities or fiscal discipline.Footnote 10

The overall empirical evidence on transfers disincentivizing subnational tax effort is, not surprisingly, somewhat mixed. In high-income countries, the empirical evidence has been inconclusive, however, with most of the studies suggesting a negative impact of transfers on tax effort (Baretti et al., 2002; Dash & Raja, 2013; Shah, 1994; Knight, 2002; Liu & Zhao, 2011; Mohanty et al., 2019; Rajaraman & Vasishtha, 2000; Zhuravskaya, 2000; ). On the other hand, several other empirical studies suggest a positive effect (see Buettner, 2006; Dahlby & Warren, 2003; Skidmore, 1999; Litschig & Morrison, 2013; Miyazaki, 2020; Zhang, 2013). In particular, Bruce et al. (2019) find no strong evidence of crowding-out in the wake of the US Department of Defense 1033 program transfers.

The situation is markedly different for developing countries, where fiscal institutions are generally weaker, and more specifically it is common for subnational governments to face significant challenges in terms of fiscal capacity. As a result, subnational governments in developing countries generally rely more heavily on intergovernmental grants to support their budgets (Bahl, 2000). In addition, weaker capacity of subnational institutions tends to be heavily associated with higher costs of local revenue collection (Fjeldstad et al., 2014; Masaki, 2018).Footnote 11 The crowding-out effect thus appears to be more pronounced in these countries. Empirical research on developing countries generally confirms that the negative effects of grants on subnational revenue generation tend to be more pronounced (Ahmad, 1997; Bhatt & Scaramozzino, 2015; Bird, 1994, 2006; Bird & Slack, 2014; Bird & Smart, 2002; Bird & Vaillancourt, 1999; Bravo, 2011; Canavire-Bacarreza et al., 2012; Canavire-Bacarreza & Zúñiga, 2010; Clist and Morrisey, 2011; Correa & Steiner, 1999; Garg et al., 2017; Jha et al., 1999; Lewis & Smoke, 2017; Miri, 2019; Mogues & Benin, 2012; Nath and Madhoo, 2022; Schroeder & Smoke, 2003; Taiwo, 2022).Footnote 12

There is, on the other hand, an interesting deviation in the behavioral response of subnational governments depending on the way their tax collection efforts are accounted for by the central government. As discussed above, the crowding-out effect of grants is often boosted by the perverse incentives set in the grant design formula, like when subnational governments receive lower transfer amounts when they increase their own revenue generation effort. To avoid this, the formulas for computing the allocation amounts can be designed on the basis of revenue potential or fiscal capacity instead of actually collected revenues. In this regard, there is empirical evidence that subnational tax effort may actually increase when tax capacity or potential tax revenues of subnational governments are used is based on instead of actual revenues. Using fiscal capacity as opposed to actual revenues in the formula frees subnational governments to collect more revenues from the fear of being penalized with lower central transfers. This evidence on crowding-in effect in developing countries has been empirically documented in many studies, including Caldeira and Rota-Graziosi (2014) for Benin; Brun and El Khdari (2016) for Morocco; Lewis and Smoke (2017) for Indonesia; Masaki (2018) for Tanzania; Miyazaki (2020) for Japan; Yousaf et al., (2022) for Pakistan; and Ajefu and Ogebe (2023) for Nigeria.

Last, we must point out that an additional reason for the divergent results in this literature might be the different estimation approaches that have been followed. If, for example, we focus on the important issue of the identification strategy, as shown in Table 1, the issue of endogeneity is quite prominent from the viewpoint of the recipient governments’ tax policy decisions; nevertheless, a good number of papers summarized there have ignored the endogeneity issue or employed non-robust external instruments. Summarizing, there is a certain lack of consensus in the empirical literature regarding the connection between intergovernmental transfers and local revenue generation; we have reviewed many studies presenting evidence for crowding-out effects, but also other studies presenting no effect, or even the opposite crowding-in effects. To be sure, some of these differences can be explained by the different allocation design employed. Other differences are likely due to specific contexts within each country, varying levels of autonomy, or diverse mechanisms that incentivize revenue mobilization.

We have also seen that the effects of grants on revenue generation differ significantly based on the level of development and institutional capacity of the countries in question. This dichotomy between developed and developing countries underscores the importance of considering the specific institutional and political contexts when analyzing the impact of grants on subnational tax effort. Weaknesses in fiscal institutions and higher costs of revenue collections in developing countries make them more susceptible to the crowding-out effect.

Going forward, further research should be welcome focused on addressing the proper identification strategies, employing robust methodologies and addressing endogeneity issues, and also on providing more nuanced explanations of the roles played by specific institutional and political contexts in both developed and developing countries. In this regard, there are already some noteworthy examples in the recent literature for how to proceed. These include research papers by Mohanty et al. (2022) using both static and dynamic panel models, Miyazaki (2020) employing a sharp RDD (regression discontinuity design) approach, and Yousaf et al. (2022) employing a combination of lagged regressor values and robust instrumental variables.

3.2 Tax competition

One potential downside of subnational government revenue autonomy is the potential presence of predatory tax competition. Tax competition involves strategic interactive relationships between subnational governments to attract or retain mobile tax bases by bringing their taxes to inefficiently low levels.Footnote 13 The empirical evidence on subnational tax competition is mostly centered on OECD countries, including Canada, Germany, Switzerland, and the USA. Tax competition is expected to vary across countries and over time, depending on fiscal and institutional frameworks (Blöchliger and Pinero-Campos, 2011).

Although alternative solutions, such as tax harmonization and cooperation, are possible, the theoretical literature on this issue has argued that central governments may use transfers to partially or fully offset the inefficiencies that ensue at the subnational level (Wilson, 1999). More specifically, several theoretical studies have examined the potential effects of equalization transfers on mitigating subnational tax competition and for regaining equilibrium efficiency (e.g., Bucovetsky & Smart, 2006; Hindriks et al., 2008; Koethenbuerger, 2002). Other scholars have also empirically explored to what extent tax-base equalization grants may lessen tax competition among subnational governments. Many of those studies have focused on the impact of Canada’s equalization system for provincial governments, which is built exclusively on disparities in fiscal capacity, and the common finding is that indeed tax competition across Canadian provinces is decreased (Boadway & Hayashi, 2001; Esteller-Moré & Solé-Ollé, 2002). In addition, more robust estimation strategies such as Smart (2007), who employs the population-weighted average of subsets of different populations as an instrumental variable, and Ferede (2017) who exploits the discontinuity in the grants allocation formula, obtained similar results. The case studies for other countries with equalization systems that consider not only disparities in fiscal capacity but also disparities in expenditure needs generally tend to find less strong results. In particular, Dahlby and Warren (2003) found only weak support the hypothesis that tax-base equalization leads to a reduction on tax competition rates at the state level in Australia. Similar weak results were found for Germany by a number of papers (Baskaran, 2014; Buettner, 2006; Buettner & Krause, 2020; Egger et al., 2009; Holm-Hadulla, 2020; Rauch & Hummel, 2015) and for Switzerland (Widmer & Zweifel, 2012). Although some of the differences in empirical findings could be due to differences in datasets and estimation methodologies, those differences appear to be quite systematic and related to specific institutional contexts.

It is worth highlighting that the recent contributions in this area have yielded more reliable estimates, thus making the conclusions drawn from the analyses more robust. Noteworthy examples include Rauch and Hummel (2015) who combine a municipal-level fixed effects model with a difference-in-differences strategy, Buettner and Krause (2020) who use a comprehensive simulation model, and Holm-Hadulla (2020) who utilizes a natural experiment setting to exploit exogenous variations in different fiscal equalization parameters. Selected papers on this section are displayed in Table 2.

3.3 Asymmetries in the effects of changes in the level of transfers

A priori one may expect that rational subnational decision-makers may react symmetrically regarding their choices of tax effort to similar increases and decreases in transfers. However, the possibility of an asymmetric response was first introduced by Gramlich (1987) who argued that cuts in transfers may be partly compensated by subnational governments willing to preserve current expenditure levels by raising additional taxes. Thus, Gramlich (1987) concluded that program spending cuts following decreases in the level of transfers could be much smaller than program expansions following increases in grants; he called this the “fiscal replacement” effect, which would lead to tax effort increases following transfer cuts.Footnote 14 The presence of this type of response has been explained by Stine (1994) as due to fiscal illusion.

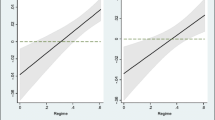

In contrast, a commonly observed behavior by subnational governments is for them to expand expenditures instead of cutting taxes in response to increases in intergovernmental transfers. This latter type of behavior, known as the “fly-paper effect”, is discussed in Sect. 3.5 in the paper. A significant body of research has found that the marginal propensity to spend when grants are rising is higher than the propensity to cut expenditures when grants are falling (Cárdenas & Sharma, 2011; Deller & Maher, 2006; Heyndels, 2001; Lago-Peñas, 2008; Levaggi & Zanola, 2003; Mehiriz & Marceau, 2014; Rios et al., 2021; Samal, 2020; Shani et al., 2023; Stine, 1994; Volden, 1999).Footnote 15

These asymmetrical effects appear to differ by the type of transfer, being lower in the case of conditional block grants than for the case of unconditional grants (Deller & Maher, 2006; Gamkhar, 2000; Goodspeed, 1998; Heyndels, 2001; Lago-Peñas, 2008; Volden, 1999).

The asymmetrical effects also appear to be mediated by institutional and political factors. Regarding the latter, for example, Lago-Peñas (2008) found that municipalities with lower levels of debt and leftist-leaning administrations are more likely to experience the "fiscal replacement" effect, maintaining expenditure levels and raising taxes in the face of grant cuts, In a similar vein, Bækgaard and Kjaergaard (2015) found that left-wing political administrations are more likely to raise spending when grants are increased and raise taxes when grants are cut. Regarding institutional factors, Rios et al. (2021) found that municipalities where incumbent authorities either make weaker enforcement efforts in tax collection or have lower margins of maneuver for budget allocations are likely to be more responsive to increases in grants.

As for other grant effects already discussed, there are several econometric issues that need to be considered in identifying the asymmetry of subnational governments’ responses. First, the earlier literature on this issue had problems in separately identifying the effects of program structure and financing institutions from the effects of variations in the levels of grant funding. Second, divergent results have been found in this literature depending on the inclusion or not of time fixed effects, the use or not of first differences, and the choice of lag lengths for the explanatory variables (Gamkhar, 2000; Goodspeed, 1998). Other estimation issues in this area of research had been raised by Levaggi and Zanola (2003), regarding heteroskedasticity and serial autocorrelation, and by Gamkhar and Oates (1996) and Knight (2002) on the potential presence of endogeneity. Consequently, robust estimation techniques have also become essential in identifying and understanding the asymmetrical responses to grants. Several recent papers have made progress in that direction. Shani et al. (2023) use a quasi-experimental design and difference-in-differences and event study methods to exploit the exogeneous reform of Israeli intergovernmental grants, and Rios et al. (2021) exploit a Bayesian spatial panel data model of almost 2451 Spanish municipalities with municipal and time-period fixed effects. Table 3 displays a representation of the papers that have been selected for this section.

3.4 Effects on government size

Research on the question of government size has a long tradition in the public finance literature starting with Wagner’s law, which associated the rise in government size with an income elastic demand for public services, to Peacock and Wiseman (1961) with a similar prediction on the faster growth of public spending than income but in a step like manner due to periodic shocks and social disturbances. Other hypotheses on the growth of government size have included the impact of rent-seeking and clientelism policies (Alesina et al., 2000) or using government as a social insurance device (Rodrik, 1997).

The level of fiscal decentralization has been traditionally seen as affecting the public sector size, but, in this case, containing its growth. Musgrave (1959) argued that decentralization would shrink redistribution policies and therefore government spending. But the best-known contribution in this regard is Brennan and Buchanan’s (1980) Leviathan hypothesis; in their view, decentralization heightens competition among government units, at the same and different levels, as they seek attract and preserve tax bases, which works to constraint “the size of the Leviathan.” The financing of subnational governments with their own tax revenues is of critical importance to the Leviathan hypothesis. When that financing is based on intergovernmental transfers, the story could change radically, and further government growth should be expected (Rodden, 2003).

A good number of papers have researched how grants can affect the size of government. The consistent finding is that the size of subnational governments increases when they are predominantly funded with intergovernmental grants, while their size decreases when subnational governments are funded with own tax revenues (Ashworth et al., 2013; Cassette & Paty, 2010; Grossman, 1989; Grossman & West, 1994; Jin & Zou, 2002; Liberati and Sachi, 2013; Makreshanska and Petrevski, 2019; Prohl & Schneider, 2009; Rodden, 2003; Shadbegian, 1999; Stein, 1999; Ye & Cao, 2022). This positive impact on government size also tends to hold when fiscally decentralized units are funded through revenues sharing or centrally regulated subnational taxation, instruments that are more akin to grants (Makreshanska-Mladenovska & Petrevski, 2019). A summary of the chosen papers in this section is presented in Table 4.

3.5 Fly-paper effect

The so-called fly-paper effect is partially related to the issue of the growth on government size. Introduced by the end of the 1960s (Gramlich, 1969; Henderson, 1968) was termed that way because it does appear that “money sticks where it hits”. The fly-paper effect is defined as the increase in lump-sum intergovernmental transfers stimulating subnational spending more than the equivalent increase in personal income. That is, funds from intergovernmental transfers tend to be used predominantly by subnational governments for increases in public spending rather than for tax relief to their residents. The existence of this effect is largely documented in the theoretical and empirical literature across countries (see Bailey & Connolly, 1998; Bradford & Oates, 1971b; Gamkhar & Shah, 2007; Hines & Thaler, 1995; Inman, 2008; Oates, 1998).

Various theoretical explanations to the causes of the fly-paper effect have been presented. For example, early on, Hines and Thaler (1995) argued that the fly-paper effect is simply an empirical anomaly. Many other studies have suggested that this phenomenon stems from the presence of fiscal illusion within subnational government operations, due to the fact that citizens misjudge and erroneously estimate the costs and benefits of their subnational governments. Essentially, the fiscal illusion explanation assumes that the median voter is only capable of observing the average cost of public expenditures, leading to an underestimation of the real marginal costs and thus to a choice to overspend. The possibility of fiscal illusion has been explored in theoretical papers (Baekgaard et al., 2016; Courant et al., 1979; Dell´Anno and Martinez-Vazquez, 2019; Mueller, 1989) and also in empirical work (Becker, 1996; Cárdenas & Sharma, 2011; Ferreira et al., 2019; Gemmell et al., 2002; Heyndels & Smolders, 1994).Footnote 16

Other authors have offered alternative causal interpretations involving the impact of politics, such as citizens’ inability to establish “political contracts” with their elected officials (Inman, 2008), the dynamic interactions between politicians and interest groups that can influence the allocation of public funds (Leduc & Wilson, 2017; Mueller, 2003; Singhal, 2008), or the political strength of local governments (Rios et al., 2021).

An additional interesting twist in some recent literature on the subject has been to see the fly-paper effect not as an anomaly or distortion but rather as a rational response in situations where subnational governments use distortionary taxes to finance at least part of their expenditures. This strand of the literature, which builds upon Hamilton (1986), focuses on the idea that transfers are more stimulative of public spending than increases in private income because grants generally can lead to a greater reduction in the marginal cost of public funds (MCPF). Henceforth, the fly-paper effect would arise as the result of maximizing welfare behavior by public governments in the presence of costly tax collection, costs which are expected to increase with the level of tax rates (Aragon, 2013; Dahlby, 2011; Ferreira et al., 2020; Mattos et al., 2018; Vegh & Vuletin, 2016).Footnote 17 Here the important obstacle has been how to measure the MCPF accurately, given that its estimation varies greatly across countries and time.Footnote 18

One last strand of the empirical literature suggests that the fly-paper effect may be due to the presence of strategic interactions and spatial local interdependence on subnational governments’ spending behavior, which are captured using spatial analysis on cross-sectional data, controlling for both spatial and time fixed effects (Acosta, 2010; Bastida et al., 2013; Kakamua et al., 2014; Yu et al., 2016).Footnote 19

To the extent that the government budget constraint relates grants with taxes, deficit and expenditure, changes in the former may also generate crowding-in and crowding-out effects on the spending side. This idea was originally introduced by Scott (1952), Bradford and Oates, (1971a, 1971b). While intergovernmental grants may involve a lower increase in expenditure because of reductions in taxes and fees, they may also generate a crowding-in effect, increasing total expenditure above the amount of the grant (Gramlich, 1977; Hines & Thaler, 1995). In this respect, for example, Lago-Peñas (2006) found an increase in investment of around 90 percent of the capital grants received by Spanish regions, with the remaining 10 percent going to reduce the deficit, thus involving a partial and small crowding out.

As mentioned before, one of the main challenges this literature faces are the presence of endogeneity of transfers due to several causes; in particular, unobserved characteristics of jurisdictions (Bailey & Connolly, 1998; Becker, 1996; Knight, 2002) and the endogenous determination of grant allocation. Using instrumental variables, the fly-paper effect fade away in earlier papers (Dollery & Worthington, 1999 for Australia; Knight, 2002Footnote 20 or Gordon, 2004Footnote 21 for the USA).Footnote 22 Nevertheless, subsequent studies relying upon this methodology have again supported the hypothesis of the fly-paper effect even after correcting for the presence of endogeneity, although more often with smaller size effects (Card & Payne, 2002Footnote 23; Cascio et al., 2013Footnote 24; Dahlberg, 2008; Lutz, 2010Footnote 25; Ferede & Islam, 2015; Gennari & Messina, 2014Footnote 26; Litschig & Morrison, 2013Footnote 27).

Moreover, the most recent studies on this topic move from standard instrumental variables econometrics to quasi-experimental designs and using discontinuities on the allocation formula to deal with endogeneity confirming an increase on subnational spending in response to grant increases near to 1. In particular, Bracco et al. (2014) for Italy, Allers and Vermeulen (2016) for the Netherlands and Baskaran (2016) for Germany find evidence for the existence of the fly-paper effect phenomenon. Liu and Ma (2015) exploit a discontinuity from the central Chinese government’s designation of National Poor Counties; Lundqvist (2015) employed a quasi-experimental research design for finish municipalities; and Leduc and Wilson (2017) exploit the exogeneous change of the apportion of ARRA highway grants.

In parallel, the most recent literature has started to implement more advanced and robust identification strategies, also yielding consistent empirical evidence in favor of the presence of a strong sizeable fly-paper effect. For instance, Langer and Korzhenevych (2019) employed two different German exogenous shocks from adjustments in the lump-sum transfer allocation formula as instruments, while Alekseev et al. (2021) conducted laboratory experiments exploring the combination of four different transfer delivery methods and three voting frameworks. Moreover, Kothenburger and Loumeau (2023) used a sharp regression kink design based on a population cut-off for Swiss municipalities.Footnote 28 Last, a recent study by Helm and Stuhler (2021) exploits a quasi-experimental variation within Germany’s fiscal equalization scheme and find evidence that the fly-paper effect is primarily a short-run phenomenon, while long-run fiscal behavior appears more consistent with standard theories of fiscal federalism.

A fair conclusion, therefore, is that our knowledge about the effects of grants on the spending behavior of subnational governments is rich and extensive, but far from complete. The contradictory nature of the findings is likely to motivate even more future empirical research on the existence and causes of the fly-paper effect. Going forward it will be useful to have a wider diversity of country studies; until now most of the empirical work on the fly-paper effect has been focused on high-income countries, where government institutions and officials likely often follow different patterns of behavior than those in low- and middle-income countries because of differences in democratization culture or administrative structure. Nevertheless, this relative lack of research in low- and middle-income countries has received recent attention, although this strand of the literature is still far from being extensive. Recent empirical analyses include work by Isik et al. (2022), who using a two-step generalized method of moments, suggests the presence of fly-paper effect in both Nigeria and South Africa. Moreover, Dick-Sagoe and Tingum (2022), Bastida et al. (2022) and Cheng-Tao et al. (2022) found strong evidence of the fly-paper effect in Ghana, Honduras, and Philippines municipalities, respectively, while Aritenang (2020), Nurlaela Wati et al., (2022) and Yudhistira et al., (2022) also find evidence for the fly-paper effect in Indonesia.Footnote 29

Future work in this area should keep prioritizing the systematic examination of various econometric concerns. As depicted in Table 5, the treatment of the endogenous allocation of grants has predominantly relied on less reliable IV instruments, neglecting the spatial correlation between the allocation and the recipient municipalities, as well as failing to account for the potential influence of political and institutional frameworks on subnational governments’ decisions. Even though significant progress has been made in the last several years, the primary challenge lies in finding more robust instruments that can exogenously capture the allocation of grants with greater validity. We have also seen that improved identification may be helped by using natural experiments and differential timing treatments. Future research should also try to differentiate between short- and long-term effects of grants, considering that, as some recent research has shown, subnational government could need some time to fully react to changes in the allocation of transfers.

4 Other induced subnational behaviors

Over the last several decades, there has been a bourgeoning of the literature examining the impact of intergovernmental grants on several other consequential behaviors of subnational governments. In this section, we focus on four types of those additional behaviors, three of which can not only harm and undermine the system of intergovernmental relations but also jeopardize the macroeconomic stability and sustainability of the national economy (Ter-Minassian, 2007). First, the timing of central transfers can contribute to the pro-cyclical spending behavior of subnational governments; second, poorly designed transfers can induce subnational perverse fiscal behaviors; and third, significant subnational transfer dependence can easily lead to several forms of subnational fiscal indiscipline. The fourth type of behavior considers how effectively transfers can be used to lead subnational governments to internalize spillover or externality effects across subnational units.

4.1 The cyclicality effects of grants on subnational fiscal choices

Depending on their timing and design, intergovernmental grants can either dampen or amplify the typical pro-cyclicality of subnational government spending. If transfers are designed as an insurance mechanism over the business cycle, they will have a dampening impact (Xing & Fuest, 2018). However, if transfers expand when the economy is growing or decrease when the economy is contracting, they will exacerbate the business cycle. As we see next below, the overwhelming evidence is that most central governments time transfers poorly which helps exacerbate the national business cycle.

Earlier empirical studies found some mixed evidence. For example, Sorensen et al. (2001) found a pro-cyclical behavior in the USA for federal grants to the states over the nationwide business cycles, while federal grants were counter-cyclical with respect to the narrower state-specific business cycles. Similarly, Arena and Revilla (2009) found that intergovernmental grants in Brazil were also counter-cyclical with respect to state-specific shocks. However, many other studies for the US and OECD countries strongly suggest that intergovernmental grants are often pro-cyclical with respect to subnational output shocks, contributing to aggravate the typical pro-cyclicality of subnational government spending (Seitz, 2000; Boadway & Hayashi, 2004; Abbott & Jones, 2012, 2013; Blöchliger & Égert, 2013; Behera et al., 2020). Two other multi-country studies suggest the predominance of pro-cyclical behavior; Rodden and Wibbels (2010)Footnote 30 find that discretionary transfers are either at best a-cyclical or pro-cyclical in seven of the largest OECD federations, while Blöchliger and Petzold (2009) found that at least half of the transfers systems of all OECD countries tend to be pro-cyclical. Table 6 displays a representation of the papers that have been chosen for this section.

4.2 Fiscal discipline

A particular type of perverse effect of the high dependence on intergovernmental grants, and which has received a great deal of attention in the previous theoretical and empirical literatures, is the weakening of fiscal discipline of subnational governments. This gets manifested into excessive spending, lower tax effort, large budget deficits and the accumulation of subnational debt, which may end in bankruptcy and bail outs by the central government. This process has been framed within the context of the soft budget constraint hypothesis developed by Kornai (1979; 1986), a soft budget constraint that is generated by the presence of transfer dependence and large vertical fiscal imbalances which weakens overall budget discipline leading to excessive borrowing and subnational indebtedness.Footnote 31 Complementarily, this effect has also been framed as part of the “common pool or tragedy of the commons” problem, where fiscal indiscipline arises because financing for subnational governments is perceived to come from taxes raised outside the jurisdiction (Alesina et al., 1999; Baskaran, 2012; Cullis & Jones, 2009; Esteller-Moré et al., 2015; Krogstrup & Wyplosz, 2010; Molina-Parra & Martinez-Lopez, 2016; Persson and Tabellini, 1996; Sanguinetti & Tommasi, 2004; Velasco, 1999, 2000; von Hagen & Harden, 1995).

An extensive empirical literature testing these perverse effects on subnational fiscal discipline from different angles has developed over the past several decades. Several studies have found strong evidence of the common pool problem explaining the generation of a deficit bias among OECD and non-OECD countries (Aldasoro & Seiferling, 2014; Debrun et al., 2008; de Mello, 1999, 2000; Eyraud & Lusinyan, 2013; Fabrizio & Mody, 2006; Foremny, 2014; Lago-Peñas et al., 2019; Neyapti, 2010; Rodden, 2002; Roubini & Sachs, 1989; Shi & Hendrick, 2020). Other studies have found strong evidence that transfer dependence and vertical fiscal imbalances lead to the expansion of subnational expenditures (Ehdaie, 1994; Jia et al., 2014; Jin & Zou, 2002; Rodden, 2003; Stein, 1999) and lower subnational tax effort (Jia et al., 2021).Footnote 32

Another group of studies have found strong evidence that dependence on grants generates an increased subnational indebtedness and expectations of a central government bail out in times of crisis (Akai & Sato, 2019; Baskaran, 2012; Baskaran et al., 2016; Braun & Trein, 2014; Calvo & Cadaval, 2021; Dietrichson & Ellegård, 2015; Djankov & Murrell, 2002; Pettersson-Lidbom, 2010; Sorribas-Navarro, 2011). In connection to this latter literature, several other papers have found that potential rescuers (central governments) are not likely to credibly commit themselves to a no-bailout policy ex ante because there exists a lot of public pressure to avoid cuts in public services such as health care or education provided by subnational governments (Crivelli & Staal, 2013; Goodspeed, 2002; Martinez-Lopez, 2022; Oates, 2005; Wildasin, 1999). And complementarily several other studies have found that indeed central governments do increase grants to those subnational governments with higher deficits and debt stocks to avoid financial stress and eventual bankruptcy (Baskaran, 2012; Buettner & Wildasin, 2006; Garcia-Milà et al., 2002; Goodspeed, 2017; Levaggi & Zanola, 2003; Pettersson-Lidbom, 2010; Sola & Palomba, 2016).

In summary, there is robust evidence on how overuse of transfers to finance subnational governments leads to important problems with subnational government fiscal discipline. Of course, this is a powerful argument in defense of subnational governments’ revenue autonomy in fiscal decentralization design. Nevertheless, the empirical literature covered in this section, as shown in Table 7, is not free of some significant econometric issues, as has been the case in other sections, including how potential endogeneity is addressed or the identification of future expectations.

4.3 Addressing externalities across subnational government units with central grants

The presence of spillover effects or externalities potentially represents one of the weakest points of decentralized governance, as flagged out in Oates’ (1972) “decentralization theorem”.Footnote 33 Subnational spillover effects have been defined as those discrepancies between the tax prices paid by citizens and the gains obtained from those services financed by those taxes (Bergvall et al., 2006). Many subnational government policies and programs can have significant positive and negative spillovers beyond their jurisdictions. This can be for very visible reasons, such as upper stream jurisdictions inflicting negative externalities on downstream ones, to more subtle reasons due to the presence of spatial interactions.Footnote 34 The complication for decentralized governance is that generally, subnational governments have little incentives to internalize those spillover effects by spending more or less on specific sectors or programs, which could benefit other subnational governments. The question that concerns us is to what extent intergovernmental grants can be successful in helping subnational governments internalize those externalities.

One important difficulty is that estimating the size of those spillovers effects across jurisdictions is a hard task due to many different complications, as highlighted by Bird and Smart (2002). This means that calibrating the size of the grant that may be needed becomes more of an uncertain task. This challenge in the quantification of the grant may help explain why the empirical literature has found mixed results on the effectiveness of using grants for addressing these inter-jurisdictional externalities. It is often argued that the best type of grant that can be used to address inter-jurisdictional externalities is a matching grant (Bergvall et al., 2006; Bezdeck & Jonathan, 1988; Bird & Slack, 1993; Blöchliger & Kim, 2016; Figuieres & Hindriks, 2002; Matsumoto, 2022; Oates, 1998; Ogawa, 2006).Footnote 35 This is because while both matching and non-matching grants stimulate spending by effectively increasing subnational governments’ ability to spend (the income effect), but only matching grants provides an additional stimulus through the lower tax price (the price effect).Footnote 36

Empirical studies on the real effectiveness of matching grants or other types of grants in reducing externalities have found mixed results, and there is some general skepticism that upper-level governments have been successful in this matter. For example, in the US context, Inman (1988), Grossman (1994) argue that the distribution of central grants reflects decisions taken by a universalistic central legislature, rather than being focused on correcting inefficiencies, and that federal transfers quite likely have been ineffective in making subnational governments internalize spillovers.

Overall, this is an area of the empirical literature on the impact of intergovernmental transfers that is under researched. Clarifying the mixed findings thus far will require to undertake case studies where externalities are well quantified and government grant interventions are clearly identified. Table 8 displays a representation of the papers that have been selected for this section.

4.4 Other perverse incentives to subnational fiscal choices

Finally, other kind of perverse incentives may arise from a design of grants. A salient quite common example is the design of equalization grant formulas incorporating the actual tax revenue collections as a measure of their fiscal capacity, thus strongly incentivizing lower subnational tax collections (Baretti et al., 2002; Bravo, 2011; Pöschl & Weingast., 2013; Weingast, 2014). Moreover, the generally right solution of using tax capacity instead of actual revenues in the equalization grant formula may actually backfire, with subnational governments raising taxes beyond what is desirable from a national viewpoint, when equalization grants overcompensate jurisdictions for the adverse effect of reduced tax bases due to increased subnational tax rates (Esteller-Moré et al., 2002; Ferede, 2017; Persson & Tabellini, 1996; Smart, 1998, 2007; Snoddon, 2003).Footnote 37

Matching clauses in the design of some conditional grants may be also troublesome because they reduce the marginal cost of spending and consequently incentivize in some cases inefficient spending (Balaguer-Coll et al., 2007; Dahlby & Warren, 2003; De Borger & Kerstens, 1996; Doumpos & Cohen, 2014; Hailemariam & Dzhumashev, 2019; Kalb, 2010; Loikkanen & Susiluoto, 2005; Toolsema & Allers, 2014; Wiesner, 2003; Zhuravskaya, 2000). However, there is some other empirical evidence indicating this may not be a generalized problem, For example, Geys and Moesen (2009) find a positive impact of grants on cost efficiency for a sample of Flemish municipalities, while Worthington (2000) finds no significant relationship between transfers and technical efficiency in the case of Australian local governments.

A more general type of perverse effect may be present when transfer funds work as “political resource curse.” Subnational governments often receive additional transfers to improve the performance of their government institutions. However, the condition of poor functioning institutions may be exacerbated by those additional resources. In this sense, for example, Brollo et al. (2013) find that additional federal transfers to municipalities in Brazil induce political corruption and lower the quality of politicians running for office, while Litschig and Morrison (2009) find, also for Brazil, that those additional transfer funds disproportionally increase the probability of the incumbent party being reelected.Footnote 38 In the particular case of equalization transfers, Kotsogiannis and Schwager (2006) argue that they reduce the intensity of political competition and lead to rent extraction behavior by incumbent officials. In a related issue, Carlino et al., (2023) found systematic differences in spending of federal funds by Democratic and Republican governors in the USA. Hence, the intended impact on spending of these transfers will not be uniform across the country.

5 Political economy: effects on autonomy and accountability

The great promise of fiscal decentralization is to be able to achieve a more efficient allocation of public resources by bringing government closer to the people and allow through diverse government units a better match of resources with people’s preferences and needs. For this to happen, subnational governments need to enjoy autonomy in their spending and taxing decisions and for public officials to be held accountable to their resident voters.

The fiscal autonomy of subnational governments has multiple dimensions, but the two most conspicuous ones are revenue and expenditure autonomy. Revenue autonomy is usually measured by the share of own revenues to total revenues in the budgets of subnational governments. The measurement of expenditure autonomy is more complex, but essentially it reflects the ability of subnational officials to make their own decisions on what public services to deliver and how to do that in making their own choices on inputs of production, etc.

It is relatively intuitive that grant financing can generally affect the level of revenue autonomy of subnational governments and that depending on the modality of the grant, especially in the case of conditional grants, expenditure autonomy can also be reduced (Furceri and Ribeiro, 2009; Rodden, 2003; Sacchi & Salotti, 2017; Stein, 1999). From this perspective, non-earmarked or unconditional intergovernmental grants are generally interpreted to be more beneficial to autonomy, and among earmarked grants, block grants are preferred to specific grants (Blöchliger & King, 2006; Martinez-Vazquez and Searle, 2006; Ladner et al., 2016).Footnote 39 Numerous papers have documented the relationship between increases in grant financing and losses in autonomy by subnational government, for example, Zhuravskaya (2000), Buettner and Wildasin (2006), Bodman and Hodge (2010), and Psycharis et al. (2016) for OECD countries, and for the case of developing countries, for example, Azis et al. (2001) and Silver (2003) for Indonesia, Mogues and Benin (2012) for Ghana, and Bongo (2019) for Sudan.

When subnational government officials lack autonomy, it becomes much harder to hold their accountable to their residents, since, after all, those officials may have little control of how budgets are implemented. Accountability has been defined as the decision by the subnational government to implement, efficiently and without corruption or patronage, the policies and budget most preferred by their citizens (Fearon, 1999).Footnote 40 The potential effect of intergovernmental grants on weakening the accountability link between subnational government elected officials and citizens has become a topic of increasing interest. The empirical research has focused on two pillars: First, individuals must know whom to assign blame or reward for policy outcomes (requiring clarity in expenditure assignments), and second, the link between tax and expenditure decisions must be clear for citizens (requiring revenue and spending authority) (Bird & Smart, 2010; Dynes & Martin, 2019; Kleider, 2018; Lago & Lago-Peñas, 2010). The fundamental issue is that practically all types of grant financing, but in different degrees, tend to weaken, if not sever, the accountability link by reducing the political costs of inefficient spending for subnational officials since they do not have to tax their residents, who will not hold officials accountable either. Grant financing also biases the balance made by voters between both sides of the budget, undermining the relation between government performance and re-election incentives (Gervasoni, 2010; Egger et al., 2009; Kalb, 2010; Litschig & Morrison, 2009; Martinez, 2005; Narbón-Perpiñá & De Witte, 2018; Oates, 1998; Rodden, 2003; Smart, 1998). A summary of the chosen papers in this section is presented in Table 9.

6 Concluding remarks

Intergovernmental grants are ubiquitous across countries, as significant public policy tools for financing subnational governments in more and less decentralized system. Transfers persist as a primary instrument in the hands of central governments to effectively address various forms of shocks and crises, as evidenced by their extensive and substantial use throughout the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic (Clemens & Veuger, 2023; de Mello & Ter-Minassian, 2022; Dougherty & de Biase, 2021).

This makes it important to systematically review and update what is known and what it is not known about both the intended and unintended effects of grants. This survey on the different effects of intergovernmental grants on subnational governments had to be, by necessity, selective. Although some relevant empirical and theoretical research on this topic may have not been included, we have strived to provide a balanced view taking stock of what is known and pointing out some areas that still will require further research.

We have seen that some different results in empirical studies are related to the different methodological estimation approaches utilized, which as is logical have been evolving over time with advances in estimation techniques dealing with such problems as endogeneity. These problems can be overcome by using more sophisticated econometric tools, such as more suitable instrumental variables and novel identification methods.

Another handicap lurking in the background is the need to improve the overall quality and quantity of subnational governments’ data. This is certainly a more general case that our understanding on the impact of transfers could be enriched by striking a better balance between cross-country analysis and single case country studies of what may be behind the heterogeneous and disparate results observed across countries.

There may also be a need to strike a better balance among the topics being researched. In comparative terms, empirical research of the fly-paper effect and the effects on the tax effort has been considerably more abundant. But that may not be the only or most policy relevant issue regarding the impact of grants. For example, we need a better understanding about the incentives or causal mechanism and the magnitudes involved for the net effect of transfers on subnational revenues generation, perverse incentives, addressing externalities, spending efficiency and accountability, and how specific institutional contexts may affect the results. But even after future research contributes to clarify the questions raised, it is probable that certain conclusions of the effects of intergovernmental grants will remain unsettled. The fly-paper effect is a good example in this regard. Despite extensive work on this topic, the presence, size, and enduring nature of this effect continue to be subject to debate and research.

In closing, considering the literature reviewed in this paper much work remains to be done on how to design, implement and measure the effects of intergovernmental grants. And there are many other areas where those potential impacts could be researched, such as constitutional design and separation of power, the disciplining of badly behaving political actors, or the role of judicial authorities.

Notes

The terms “transfers” and “grants” are used interchangeably in the paper. Generally, we use the terms intergovernmental transfers or grants for funds payable to any level of government by other levels of government.

Those grants which are conditional are open use or only dedicated to recurrent or capital expenditures? If otherwise unconditional transfers may only be used for investment purposes, there may be issues about whether the recipient governments later cover the operation and maintenance costs of the infrastructure financed by the development transfers.

Among the ex ante conditional grants, a further distinction is made between specific or categorical grants and block grants. In the case of the former, the conditionality is detailed and obligates subnational governments to spend funds into narrow areas with little choice. In contrast, block grants just target specific areas of spending but provide considerably more discretion on how the funds are spent by subnational governments. The clear greater autonomy provided by block grants has been often used to proclaim their superiority over specific grants, but in fact these latter may be more effective instruments in achieving certain types of national objectives; they are also less prone to intergovernmental controversy. For further information on taxonomies of grants, see Bahl, Boex and Martínez-Vázquez (2001), Bergvall et al. (2006), Boadway and Shah (2007), Searle and Martínez-Vázquez (2007), and Spahn (2012).

On an additional dimension, matching grants can be open-ended, if there is no limit to the amount of funding that can be received, or close-ended, if the amount of funds available is capped at some level. Shah (2007) argues that closed-ended grants stimulate the spending on public goods and services more than open-ended transfers.

Using one of the most salient examples, in the case of equalization grants, no general agreement has been reached in both the theoretical and empirical fiscal equalization literatures on the optimal design features of a universal fiscal equalization scheme (e.g., Johansson, 2003; Kalb, 2010; Albouy, 2012, or Simon-Cosano et al., 2013) This lack of consensus emerges also in numerous comparative studies (e.g., Dabla- Norris, 2006 for transition countries; Peteri, 2006 for Southeast European countries; Shah, 2007 for industrialized countries; or Blöchliger, et al., 2007 for OECD countries).

For instance, conditional grants have a smaller stimulating impact on local revenue compared to unconditional transfers (Brun and El Khdari, 2016).

In terms of local revenue generation, Africa has exhibited a comparatively worse performance when compared to the global standards (Masaki, 2018).

See also Bahl and Bird (2018) for an extensive discussion on subnational government revenue generation issues in developing countries.

However, other scholars have argued that tax competition may be welfare improving. For complete surveys of the literature on tax competition, see Zodrow (2001), Guimarães Ferreira et al. (2005), Zodrow (2010) and Baskaran and Lopes da Fonseca (2013). Perhaps more relevant for this paper is the recent comprehensive review of tax competition by Agrawal et al. (2022) who among other things examine the effect of grants, especially equalization grants, on local government tax choices.

In this regard, Marattin et al. (2022), using a difference-in-discontinuities, find that a contraction of intergovernmental grants in Italian municipalities led to an increase in taxes rather than a cut in spending.

However, some authors have found that not to be the case. In particular, Gamkhar and Oates (1996), using US aggregate time-series data on state and local expenditures, found no asymmetries in response to cuts and increases in transfers, and Gennari and Messina (2014) obtained similar results for the case of Italian municipalities.

To be noted, many of these latter studies may have suffered from the presence of endogeneity, this time in the measurement of fiscal illusion. Intergovernmental grants are likely to be endogenously determined by political and socioeconomic factors that may distort subnational behavioral responses and grants allocation itself, and by fiscal competition and asymmetric information issues (Khemani, 2007; Boex and Martínez-Vázquez, 2005). See Knight (2002) and Ichimura and Todd (2007) for the use of a variety of techniques, including Instrumental Variable (IV) estimators to address the potential endogeneity of fiscal illusion.

Note that Sepúlveda (2017) has argued that the fly-paper effect does not require the MCPF to be increasing in the tax rate, but only to be greater than one and non-decreasing in the tax rate.

Some of those differences may also be due to the different methodologies employed (e.g., Auriol and Warlters, 2012; Dahlby, 2008). Another layer of complexity and source of variation has been the different instrumental variable used to address the issue of endogeneity. For example, Buettner and Fabritz (2014) used differences in subnational employment as an instrument, while Dahlby and Ferede (2015) relied upon the weighted average of personal income taxes in other jurisdictions.

An extension of this strand of literature is performed by Rios et al. (2021) who employed a spatial panel data framework to account for unobserved spatial and temporal variability.

Knight (2002), after controlling for endogeneity of grant amounts federal highway funding to states, suggested that some observed flypaper effects may just be statistical artifacts.

Specifically, Gordon (2004) studied the effects of the Title I program in the USA, a program that transfers nonmatching resources to school districts targeting their number of poor children. She employed a discrete change in the census-based index of poverty to estimate state-level effects to correct for endogeneity.

To be noted, most of these papers only studied specific grant programs within the Australia and the US contexts. For those reasons, their external validity and robustness have been questioned; there has been also some questioning about the exogeneity of the instruments they utilized.

These authors studied the effects of school finance reforms between 1977 and 1992 on US states spending. They employed state Supreme Court decisions as instrumental variables for state educational grants-in-aid. They reported that a one-dollar-increase in state aid raised district education spending by 50 to 65 cents.

Cascio et al. (2013) showed an expansion in school spending of 50 cents per dollar in the average Southern school district in the USA. They also studied the implications of the Title 1 program, focusing on the Southern states in the US, but employing the per-pupil current expenditure using 1960 child poverty rate as an instrument of the federal revenue.

He studied the effect of state-wide school finance reform in New Hampshire, using reform grants per pupil as an instrument of the allocation of transfers. He found that that one dollar of additional transfers on education spending results in an increase of less than 0.2 dollars.

Gennari and Messina (2014) combine Italian municipalities’ panel data with the use of instrumental variables, and they found a fly-paper effect larger than one.

They estimated the impact of intergovernmental transfers, under the unconditional program "Fundo de Participação dos Municípios (FPM)" in Brazil, using RDD models based on multiple population cutoffs to address endogeneity. They showed that transfers increased local government spending per capita by about 20 percent over a 4-year period.

An interesting point in Koethenbuerger and Loumeau (2023) work is their focus on the effect of grants on different spending categories. These authors found that grants increase three Swiss administrative categories: administration, infrastructure, and police, while no significant effect is observed for public education and social spending. Similarly, Lundqvist et al., (2015) had found a positive effect on spending in administration.

A notable work that focuses on low and middle-income countries is the empirical study by Ğbafi and Saruç (2004). The authors follow a cross-section and panel data analysis between 1995 and 1998 and find the presence of a fly-paper effect in 52 Turkish provinces.

The list of OECD countries analyzed by Rodden and Wibbels (2010) included Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Germany, India, Spain, and the USA. Interestingly, they found a clearly not pro-cyclical behavior in the case of Australia, although it was the country with the fewest data points.

We should note that some authors have argued that certain level of vertical fiscal imbalance may be instrumental for the central government to pursue certain political and economic objectives (Boadway and Keen, 1996; Dahlby, 1996).

Conversely, Makreshanska-Mladenovska and Petrevski (2021), using a panel of 11 former transition countries in Central and Eastern Europe during 1991–2018, find that intergovernmental grants did not have detrimental effects on the overall fiscal discipline of those countries.

Institutions of political decentralization, such as the level of national political party integration, can have important mitigation effects on subnational government externalities (Ponce-Rodríguez et al., 2020).

The seminal paper on spatial interactions by Case, Hines and Rosen (1993) reported a positive effect of the neighbors’ expenditure levels on local per capita expenditure. Similarly, Dahlberg and Edmark (2008) found a positive effect of the welfare level in neighboring municipalities on local welfare. Other studies on the presence of spatial spillovers include Hanes (2002), Lundberg (2006), Birkelöf (2009) and Stastna (2009).

Bergvall et al. (2006) suggest that earmarked matching grants are indeed efficient instruments to internalize national spillovers, but they may fail to internalize regional spillovers. The reason for this is that these types of transfers may incentivize the national taxpayer to pay for those services that exclusively benefit sub-national residents.

In addition, Wildasin (1999) argues that the internalization of externalities is likely affected by the size of the locality receiving the grant allocation, which may matter little for larger size subnational budgets.

A similar problem may arise when equalization grant formulas are based on a representative tax system, such that when a subnational government raises its tax rate, it may obtain higher equalization transfers by the effect its policy has on an increased national standard tax rate used in the formula (Ferede, 2017; Smart, 1998).

For a review of Brazil´s intergovernmental grants system and three cases of performance-based transfers, see Wetzel and Viñuela (2020).

Of course, block grants with general earmarking to some areas of expenditure are still more restrictive for autonomy than general-purpose or unconditional grants. See Bergvall et al. (2006) for a detailed discussion of block and general-purpose grants.

In situations of weak subnational government autonomy, and in the absence of the preferred horizontal accountability, vertical accountability to the central authorities is often seen as an imperfect substitute to generate some sort of indirect subnational government accountability to their residents. In this situation, conditional grants (in particular, specific earmarked grants) are more likely to generate that vertical accountability.

References

Abbott, A., & Jones, P. (2012). Intergovernmental transfers and procyclical public spending. Economics Letters, 115, 447–451.

Abbott, A., & Jones, P. (2013). Procyclical government spending: A public choice analysis. Public Choice, 154, 243–258.

Abdullatif, E. (2006). Crowding-out and crowding-in effects of government bonds market on private sector investment (Japanese case study). Institute of Developing Economies, Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO), IDE Discussion Papers

Acosta, P. (2010). The flypaper effect in presence of spatial interdependence: Evidence from Argentinean municipalities. The Annals of Regional Science, 44(3), 453–466.

Agrawal, D. R., Hoyt, W. H., & Wilson, J. D. (2022). Local policy choice: Theory and empirics. Journal of Economic Literature, 60(4), 1378–1455.

Ahmad, E. (1997). Financing decentralized expenditures. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Ajefu, J., & Ogebe, J. O. (2023). Impact of intergovernmental transfers on household multidimensional well-being. The Journal of Development Studies, 59(3), 381–397.

Akai, N., & Sato, M. (2019). The role of matching grants as a commitment device in the federation model with a repeated soft budget setting. Economics of Governance, 20(3), 23–39.

Albouy, D. (2012). Evaluating the efficiency and equity of federal fiscal equalization. Journal of Public Economics, 96, 824–839.

Aldasoro, I., & Seiferling, M. (2014). Vertical fiscal imbalances and the accumulation of government debt. IMF Working Papers 14/209, International Monetary Fund.

Alekseev, A., Alm, J., Sadiraj, V., & Sjoquist, D. L. (2021). Experiments on the fly. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 186, 288–305.

Alesina, A., Reza, B., & Easterly, W. (2000). Redistributive public employment. Journal of Urban Economics, 48(2), 219–241.

Alesina, A., Roubini, N., & Cohen, G. (1999). Political cycles and the macroeconomy. MIT Press.

Allers, M. A., & Vermeulen, W. (2016). Capitalization of equalizing grants and the flypaper effect. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 58, 115–129.

Aragon, F. M. (2013). Local spending, transfers, and costly tax collection. National Tax Journal, 66(2), 343–370.