Abstract

Poor self-rated health (SRH) is associated with incident arterial cardiovascular disease in both sexes. Studies on the association between SRH and incident venous thromboembolism (VTE) show divergent results in women and no association in men. This study focuses on the association between change in SRH and incident VTE in a cohort of 11,558 men and 6682 women who underwent a baseline examination and assessment of SRH between 1974 and 1992 and a re-examination in 2002–2006. To investigate if changes in SRH over time affect the risk of incident VTE in men and women. During a follow-up time from the re-examination of more than 16 years, there was a lower risk for incident VTE among women if SRH changed from poor at baseline to very good/excellent (HR 0.46, 95% CI 0.28; 0.74) at the re-examination. Stable good SRH (good to very good/excellent at the re-examination, HR 0.60, 95% CI 0.42; 0.89), or change from good SRH at baseline into poor/fair at the re-examination (HR 0.68, 95% CI 0.51; 0.90) were all significantly associated with a reduced risk for VTE. All comparisons were done with the group with stable poor SRH. This pattern was not found among men. Regardless of a decreased or increased SRH during life, having an SRH of very good/excellent at any time point seems to be associated with a decreased risk of VTE among women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Highlights

-

In this cohort, men had a higher incidence of VTE compared with women.

-

A good SRH anytime during life is associated with a lower risk of VTE in women.

-

There was no association between the risk of VTE and SRH nor between VTE and changed SRH among men.

-

The role of changed SRH regarding different incident diseases should be further investigated.

Background

Venous thromboembolism has several major risk factors, and some of these have been found to be associated with poor self-rated health (SRH), such as high body mass index (BMI) [1], smoking [2] and physical inactivity [3].

Poor SRH is associated with premature mortality and numerous morbidities [4, 5], which can only partly be explained by the patient’s medical history, cardiovascular risk factors, and socioeconomic characteristics [6, 7]. Studies have also described an association between poor SRH and altered biological markers such as heart rate, glycemic status, and inflammation [8].

Several longitudinal studies of individual changes in SRH over time have shown that SRH seems to be a stable indicator of incident disease, especially in elderly individuals [9, 10], even though the subjective evaluation of SRH among elderly patients may not reflect the decline in objectively measured health. This might be explained by an adaptation to worsening physical conditions with increasing age [11].

However, the relationship between poor SRH and VTE has not been well studied. Previous studies have shown contradictory results with a significant association between poor SRH and VTE only among women [12, 13]. Meanwhile, even if sex differences regarding VTE incidence remain controversial, it has been suggested that biological mechanisms might contribute to the increased incidence for men [14].

The aim of the present study was to investigate whether changes in SRH over the life-course are related to incident VTE in Malmö Preventive Programme of 33 346 individuals.

Methods

Study population

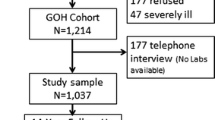

Men and women aged 35–70 in the urban area of Malmö, southern Sweden, were invited to participate in a screening programme initiated by the Section of Preventive Medicine, Department of Medicine, University Hospital with a start in 1974, Malmö Preventive Project (MPP). A total of 22,444 men and 10,902 women were included between 1974 and 1992, with an overall attendance rate of 71% [15,16,17].

A total of 11,558 men and 6682 women attended the re-examination between 2002 and 2006 [18]. The median time between baseline and re-examination was 25.5 years for men and 19.6 years for women. All participants were traced in validated national registers [19] until December 31st, 2018. The median follow-up time from the re-examination was 12.8 years for men and 13.6 years for women.

Measurements and definitions

SRH at baseline between 1974 and 1992 was assessed by a dichotomous question: ‘Do you feel perfectly healthy? Yes/No’. The answers were translated into good/poor SRH. At the re-examination between 2002 and 2006, a single question with five answering alternatives was used; very poor, poor, good, very good, and excellent. In the present study, based on the distribution, we dichotomized the SRH at re-examination into poor/fair (very poor, poor, and good) and very good/excellent (very good and excellent). In addition to the question about their perceived health, the re-examination questionnaire included data on reported alcohol consumption, smoking, leisure time physical activity, medication, diseases, measures of hip circumference, waist circumference, and experienced symptoms. Data about VTE diagnoses (Supplementary Table 1), and other diagnoses for exclusions were collected using ICD diagnostic codes from the Swedish Hospital Discharge Register and the Hospital Outpatient Register, and data about cancer diagnoses were retrieved from the Swedish Cancer Register [20,21,22].

Confounders

We adjusted the multivariate analysis with the following confounders: age [23], smoking [14, 24, 25], varicose veins [26] and waist circumference [27, 28], as waist circumference is a better predictor for VTE than BMI [29, 30].

Statistical analysis

The stratification between the sexes was confirmed by an interaction analysis. Baseline characteristics and VTE incidence rates for the studied population were calculated using descriptive statistics. The associations between SRH change and VTE were calculated by Cox proportional regression analyses with hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). The analyses were done in several steps, starting with a univariate analysis to examine the hazard for each different potential confounder. In the multivariate analysis, we added the potential confounders that were significantly associated with VTE in three steps. STATA 16.1 was used to perform all analyses.

Exclusion

A total of 3578 men and 1604 women were excluded from the main analysis due to prevalent disease associated with increased risk for VTE before re-examination [31,32,33].

Results

There were 7937 men with 354 incident VTE cases and 5066 women with 269 incident VTE cases during a follow-up time from the re-examination of 16.2 years (men) and 16.8 years (women). The sum of the follow-up time for men was 76 745.602 person-years and 55 842.891 person-years for women, corresponding to an incidence rate of 4.61 per 1000 person-years (95% CI 4.51; 5.12) for men and 4.82 per 1000 person-years (95% CI 4.27; 5.42) for women.

The interaction test showed a significant difference between sex and SRH with a p-value < 0.05. A group comparison analysis showed significant differences between the groups with incident and non-incident VTE among women only at baseline regarding SRH (p = 0.007) (supplementary Table 2). Stable good SRH, or good SRH at either baseline or re-examination were all associated with a significantly reduced risk for VTE, compared with rating the health as poor at both baseline and re-examination (Fig. 1).

After an adjustment for age, all SRH change groups were associated with a significantly reduced risk for VTE (Table 1). The association remained significant even when the analysis was fully adjusted with age, smoking, waist circumference, and varicose veins (Table 1).

In the sensitivity analysis to test the robustness of the analysis, the association between SRH change and VTE remained significant, using prevalent VTE, prevalent malignancy, and medication with Warfarin as exclusion criteria (Supplementary Table 4 & 5).

Regardless of exclusions, there was no association between change in SRH and incident VTE among men, neither in the univariate analysis nor after the fully adjusted analysis.

Discussion

The lowest risk for incident VTE was found in women whose SRH changed from poor to very good/excellent. However, we found an association with a 32% lowered risk for VTE among those women who had changed their SRH from good to poor/very poor. This means that women who once rated their health as good had a lower risk for VTE compared with those women who continuously rated their health as poor throughout their lives.

The results differ from studies with CVD, where rating SRH as poor is associated with an increased risk of CVD [5, 34] as well as with mortality [35, 36] in both men and women. Even if the prevalence of VTE is higher among men [37], our results might be explained by the fact that women generally report poorer health than men [38]. This is in line with previous studies showing that despite the subjective assessment of health is poorer among women, they are healthier [39, 40] and have longer life expectancy than men [40, 41].

The presence of economic crises in society may be one explanation for the changes in SRH, where more women than men seem to be affected negatively [42]. Recent research has also claimed that personal finances can disrupt the assessment of one’s self-rated health [43] and should be adjusted for. The re-examination was made between 2002 and 2006, when the unemployment rate was lower compared to during the economic crisis in Sweden during 1990–1994 [44] and, prior to the economic crisis causing a recession period in Europe between 2008 and 2011 [42]. Therefore, the self-reported SRH at the re-examination should not be affected by major societal changes.

Strengths and limitations

The lack of socioeconomic data or hospitalizations is a limitation of the study. Another limitation is the lack of psychological status assessment and personality traits, which can also influence the experienced SRH [45, 46].

A further limitation of the study is the variation in SRH assessment in baseline and re-examination. However, as SRH is considered a stable indicator over time, we believe that this had a minor impact on our results.

A study on long-term trajectories of SRH showed that a decline in SRH had already started before the diagnosis leading to subsequent death [47]. Our study showed that rating SRH as good at least once during the follow-up time lowers the risk for incident VTE and is, therefore, a potentially useful indicator for early efforts to assess a patient’s risk for consequent disease among women. As around 23% of women in Sweden rate their health as not good [48], it may have a considerable impact on the incidence of VTE. Besides the association between SRH and VTE among women found in our study, SRH has also been found to be associated with altered biological markers [8] and of importance for the development of incident VTE [49].

Conclusion

Regardless of a decreased or increased SRH during life, having an SRH of very good/excellent at any time point seems to be associated with a decreased risk of VTE among women. The clinical implication of the present study could be to include recurring assessments of SRH in primary care.

Data availability

Due to ethical and legal restrictions related to the Swedish Biobanks in Medical Care Act (2002:297) and the Personal Data Act (1998:204), data are available upon request from the data access group of MPP Study by contacting Anders Dahlin (anders.dahlin@med.lu.se).

References

Sung ES et al (2020) The relationship between body mass index and poor self-rated health in the South Korean population. PloS one 15(8):e0219647

Wang F et al (2012) Long-term association between leisure-time physical activity and changes in happiness: analysis of the Prospective National Population Health Survey. Am J Epidemiol 176(12):1095–1100

Han S (2021) Physical activity and self-rated health: role of contexts. Psychol Health Med 26(3):347–358

Bamia C et al (2017) Self-rated health and all-cause and cause-specific mortality of older adults: Individual data meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies in the CHANCES consortium. Maturitas 103:37–44

Mavaddat N et al (2014) Relationship of self-rated health with fatal and non-fatal outcomes in cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS one 9(7):e103509

Lijfering WM et al (2011) Relationship between venous and arterial thrombosis: a review of the literature from a causal perspective. Semin Thromb Hemost 37(8):885–896

Kivimäki M et al (2017) Overweight, obesity, and risk of cardiometabolic multimorbidity: pooled analysis of individual-level data for 120 813 adults from 16 cohort studies from the USA and Europe. Lancet Public Health 2(6):e277–e285

Jarczok MN et al (2015) Investigating the associations of self-rated health: heart rate variability is more strongly associated than inflammatory and other frequently used biomarkers in a cross sectional occupational sample. PloS one 10(2):e0117196

Gregson J et al (2019) Cardiovascular Risk factors associated with venous thromboembolism. JAMA Cardiol 4(2):163–173

Armstrong ME et al (2015) Frequent physical activity may not reduce vascular disease risk as much as moderate activity: large prospective study of women in the United Kingdom. Circulation 131(8):721–729

Warburton DER, Bredin SSD (2017) Health benefits of physical activity: a systematic review of current systematic reviews. Curr Opin Cardiol 32(5):541–556

Nymberg P et al (2020) Self-rated health and venous thromboembolism among middle-aged women: a population-based cohort study. J Thromb Thrombolysis 49(3):344–351

Nymberg P et al (2022) Association between self-rated health and venous thromboembolism in Malmö Preventive Program: a cohort study. Prev Med 159:107061

Zhang G et al (2014) Smoking and risk of venous thromboembolism: a systematic review. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 45(3):736–745

Trell E (1983) Community-based preventive medical department for individual risk factor assessment and intervention in an urban population. Prev Med 12(3):397–402

Nilsson P, Berglund G (2000) Prevention of cardiovascular disease and diabetes: lessons from the Malmo Preventive Project. J Intern Med 248(6):455–462

Berglund G et al (1996) Cardiovascular risk groups and mortality in an urban swedish male population: the Malmö Preventive Project. J Intern Med 239(6):489–497

Leosdottir M et al (2011) The association between glucometabolic disturbances, traditional cardiovascular risk factors and self-rated health by age and gender: A cross-sectional analysis within the Malmö Preventive Project. Cardiovasc Diabetol 10(1):118

Ludvigsson JF et al (2011) External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health 11(1):450

Zöller B et al (2011) Age- and gender-specific familial risks for venous thromboembolism: a nationwide epidemiological study based on hospitalizations in Sweden. Circulation 124(9):1012–1020

Zoller B et al (2011) Venous thromboembolism does not share strong familial susceptibility with coronary heart disease: a nationwide family study in Sweden. Eur Heart J 32(22):2800–2805

Rosengren A et al (2008) Psychosocial factors and venous thromboembolism: a long-term follow-up study of Swedish men. J Thromb Haemost 6(4):558–564

Barco S et al (2019) Impact of sex, age, and risk factors for venous thromboembolism on the initial presentation of first isolated symptomatic acute deep vein thrombosis. Thromb Res 173:166–171

Deflandre E et al (2016) Obstructive sleep apnea and smoking as a risk factor for venous thromboembolism events: review of the literature on the common pathophysiological mechanisms. Obes Surg 26(3):640–648

Mendoza-Romero D et al (2019) Impact of smoking and physical inactivity on self-rated health in women in Colombia. Prev Med Rep 16:100976

Nordstrom SM, Weiss EJ (2008) Sex differences in thrombosis. Expert Rev Hematol 1(1):3–8

Yang G, De Staercke C, Hooper WC (2012) The effects of obesity on venous thromboembolism: a review. Open J Prev Med 2(4):499–509

Allman-Farinelli MA (2011) Obesity and venous thrombosis: a review. Semin Thromb Hemost 37(08):903–907

Borch KH et al (2010) Anthropometric measures of obesity and risk of venous thromboembolism: the Tromso study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 30(1):121–127

Yuan S et al (2021) Overall and abdominal obesity in relation to venous thromboembolism. J Thromb Haemost: JTH 19(2):460–469

Franchini M, Mannucci PM (2008) Venous and arterial thrombosis: different sides of the same coin? Eur J Intern Med 19(7):476–481

Prandoni P (2009) Venous and arterial thrombosis: two aspects of the same disease? Eur J Intern Med 20(6):660–661

Prandoni P (2017) Venous and arterial thrombosis: is there a link? Adv Exp Med Biol 906:273–283

van der Linde RM et al (2013) Self-rated health and cardiovascular disease incidence: results from a longitudinal population-based cohort in Norfolk, UK. PloS one 8(6):e65290

Heidrich J et al (2002) Self-rated health and its relation to all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in Southern Germany. Results from the MONICA augsburg cohort study 1984–1995. Ann Epidemiol 12(5):338–345

Heistaro S et al (2001) Self rated health and mortality: a long term prospective study in eastern Finland. J Epidemiol Community Health 55(4):227

Roach REJ, Cannegieter SC, Lijfering WM (2014) Differential risks in men and women for first and recurrent venous thrombosis: the role of genes and environment. J Thromb Haemost 12(10):1593–1600

Boerma T et al (2016) A global assessment of the gender gap in self-reported health with survey data from 59 countries. BMC Public Health 16(1):675

Crimmins EM, Kim JK, Solé-Auró A (2011) Gender differences in health: results from SHARE, ELSA and HRS. Eur J Public Health 21(1):81–91

Bora JK, Saikia N (2015) Gender Differentials in self-rated health and self-reported disability among adults in India. PloS one 10(11):e0141953

Barford A et al (2006) Life expectancy: women now on top everywhere. BMJ 332(7545):808

Abebe DS, Tøge AG, Dahl E (2016) Individual-level changes in self-rated health before and during the economic crisis in Europe. Int J Equity Health 15:1–1

Baidin V, Gerry CJ, Kaneva M (2021) How self-rated is self-rated health? Exploring the role of individual and institutional factors in reporting heterogeneity in Russia. Soc Indic Res 155(2):675–696

Åhs A, Westerling R (2006) Self-rated health in relation to employment status during periods of high and of low levels of unemployment. Eur J Pub Health 16(3):294–304

Goodwin R, Engstrom G (2002) Personality and the perception of health in the general population. Psychol Med 32(2):325–332

Stephan Y et al (2020) Personality and self-rated health across eight cohort studies. Soc Sci Med 263:113245

Stenholm S et al (2016) Trajectories of self-rated health in the last 15 years of life by cause of death. Eur J Epidemiol 31(2):177–185

Folsom AR et al (2020) Resting heart rate and incidence of venous thromboembolism. Res Pract Thromb Haemost 4(2):238–246

Johansson SE et al (2015) Longitudinal trends in good self-rated health: effects of age and birth cohort in a 25-year follow-up study in Sweden. Int J Public Health 60(3):363–373

Berglund G et al (2000) Long-term outcome of the Malmö preventive project: mortality and cardiovascular morbidity. J Intern Med 247(1):19–29

Johnson LS et al (2017) Serum Potassium is positively associated with stroke and mortality in the large population-based Malmö Preventive Project cohort. Stroke 48(11):2973–2978

Zaigham S et al (2020) Low lung function and the risk of incident chronic kidney disease in the Malmo Preventive Project cohort. BMC Nephrol 21(1):124

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank science editor Patrick O'Reilly for his useful comments on the text.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Halmstad University. This work was supported by grants from Sparbanken Skåne (Zöller), the Swedish Research Council (Zöller), and Avtal om Läkarutbildning och Forskning (ALF) funding from Region Skåne (Zöller).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PN, VMN, S.C, and BZ contributed to data analyzes and drafting. All authors revised the article and gave final approval of the final version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Ethical approval and consent to participants

The need of written consent was waived at baseline by the ethics review board [50, 51], but all participants agreed to participate via verbal informed consent. Data collection was therefore not approved by any ethics committee at baseline as it was a part of the health care routine system. However, the screening programme was approved by the Health Service Authority of Malmö [15, 50, 52] as a part of an extensive preventive medical action aimed at the population in Malmö. However, the regional ethics committee at Lund University approved (2004–85) the prospective follow-up studies of the cohort, and participants were given an opportunity to opt-out through an advertisement in local newspapers [44]. The Malmö Preventive Project Re-examination Study (2002–2006) was approved by the regional Ethics Committee in Lund, Sweden (No. LU 244–02), and all participants in the re-exam gave informed written consent. Data collection and analysis were carried out in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to publication

Not Applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nymberg, P., Milos Nymberg, V., Calling, S. et al. Association between changed self-rated health and the risk of venous thromboembolism in Malmö Preventive Program: a cohort study. J Thromb Thrombolysis 57, 497–502 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-023-02933-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-023-02933-4