Abstract

Despite limited opportunities for tenured academic positions, the number of PhD graduates in Social Sciences has steadily risen in countries with developed research systems. The current literature predominantly portrays PhD graduates as victims, either of the higher education system or of their own optimism in pursuing an academic career. This paper takes an alternative stance by spotlighting the agency exhibited by PhD graduates in Social Sciences as they deftly navigate their career pathways amid the constrained academic job market. Specifically, we adopt an ecological perspective of agency to explore how PhD graduates in Social Sciences exercise their agency in navigating their career from the beginning of their PhD candidature until up to 5 years after graduation. We employ a narrative approach to delve into the employment journeys of twenty-three PhD graduates. Within this cohort, we select to report four participants from four Australian universities, each possessing distinct career trajectories. Our analysis highlights agency as the link between various personal and institutional factors that shape our participants’ career trajectories. Based on this finding, we offer recommendations for practice and policy changes that appreciate PhD graduates’ agency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There has been a significant surge in the number of new PhD graduates over the past few decades in countries with developed research systems (Buenstorf et al., 2023; Hancock, 2023; OECD, 2021). However, academic job markets have shrunk considerably (Guerin, 2020), with decreased percentages of tenure academics in Australia (Crimmins, 2017; Lama & Joullié, 2015), the USA (Feder, 2018; Hayter & Parker, 2019), the UK as well as many other European countries (Feder, 2018; Germain-Alamartine et al., 2021; OECD 2021). Research on labour markets for PhD holders has identified several prominent labour market trends (despite specific variations across nations). These include a growing availability of non-academic opportunities for PhD holders in the USA (Hayter & Parker, 2019) and other OECD countries (OECD 2021), a shift towards temporary and contract positions especially in the higher education sector in the UK and Australia (Hancock, 2023; Croucher, 2023), stronger ties with industry and entrepreneurship in European countries such as the UK, Norway, Sweden, and Italy (Hancock, 2023; Germain-Alamartine et al., 2021; Marini, 2022), and increased global mobility across OECD countries (Auriol et al., 2013). These trends emphasise the importance of a broader perspective on career possibilities for PhD holders in a dynamic job market.

Academic job markets exhibit variations depending on the national system. For instance, recent cohorts of doctoral graduates in Germany are more engaged in university-based professional jobs (e.g. administration and management positions) (Buenstorf et al., 2023, p. 1218). By contrast, recent census data in Australia suggests a growing trend of PhD graduates seeking employment opportunities beyond the academic sector (McCarthy & Wienk, 2019). Likewise, more PhD graduates in the UK pursue non-academic career paths (Hancock, 2023; McAlpine et al., 2013). Regardless of the national differences, a decline in tenured academic positions and increased use of academics on a contingent contract basis is a common trend in countries with developed research systems that need further investigation.

In terms of aspiration, a survey in Australia shows that nearly two-thirds of PhD students in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) want to find a job in an industry or the public sector; in contrast, only one-third of PhD students in Social Sciences indicate their intention to look for work outside academia (McCarthy & Wienk, 2019). Top employers of PhD graduates are Banking and Finance, Information Technology, Engineering, Energy and Mining, Medical and Pharmaceutical sectors (McCarthy & Wienk, 2019), which look for STEM experts rather than social scientists. Within academia in a broader context, PhD graduates in Social Sciences in OECD countries are less likely to have full-time research fellowship opportunities, meaning fewer opportunities leading to secure employment (Auriol, 2010). UK PhD graduates in Social Sciences find more opportunities in non-research positions than their counterparts in STEM (Hancock, 2023). These findings suggest that career opportunities for PhD graduates in Social Sciences are limited both inside and outside academia.

Despite the large body of literature underscoring job security issues, little is known about how PhD graduates in Social Sciences navigate their career pathways in such a gloomy employment landscape. Addressing this gap, this study explores the stories of PhD graduates in Social Sciences to examine how they consider career options and make decisions from the beginning of their candidature until up to 5 years after graduation. The next section will present the literature that casts light on various career pathways available for PhD graduates in Australia. It is then followed by discussions about the agency of PhD graduates in navigating their career progression.

Common career pathways for PhD graduates

Inside academia

In Australia, a PhD graduate can follow two main academic career routes: the lecturer pathway (teaching and research positions) and the postdoctoral pathway (research-only positions) (Rogers & Swain, 2022). Both routes have equivalent academic titles, which are ranked from levels A to E. Table 1 shows the titles used in most Australian universities.

The postdoctoral pathway, more common amongst those in STEM, especially in the biomedical sciences, is research-focused and often starts with a research assistant position (level A). PhD graduates in Social Sciences and Humanities tend to take the teaching and research pathway, which normally starts with teaching associate positions (level A). For both pathways, academic positions that offer continuing employment often start at level B.

The above two pathways are not distinctive routes. In fact, it is common to find PhD graduates switching between precarious teaching and research positions with no permanent employment opportunities entailed (Menard & Shinton, 2022; Spina et al., 2022). Alarmingly, there is an increase in the number of teaching-only staff, considered “second class”, accounting for around 80% of the casual academic workforce because they are loaded with heavy teaching and do not often have opportunities, time, and support to conduct research (Bennett et al., 2018, p. 282). Without strong track records in research, they are unlikely to be offered a long-term employment contract (Rogers & Swain, 2022). The time taken to obtain one can extend to 10 years or more after the completion of doctoral study (Nadolny & Ryan, 2015).

Outside academia

The employment landscape for PhD graduates outside academia has become more and more promising. The rise of knowledge-based economies has promoted collaboration between academia and industry and made available career options outside of academia to PhD graduates (Hancock, 2023; Priestley et al., 2015). Although people may be optimistic about career prospects outside of academia (Waaijer, 2017), there are certain challenges involving adapting to the requirements of industries. Research indicates that PhD graduates often find it difficult to transition from Higher Education to other sectors because of their lack of industrial experience, the mismatch between the job market’s demand and their skill sets (Jackson & Michelson, 2016) or their lack of skills to sell themselves in the market (Boulos, 2016). Further, industry leaders tend to show reluctance to hire PhD holders due to their lack of understanding about the potential and values of these graduates for their organisations (Couston & Pignatel, 2018). To succeed outside of academia, PhD graduates, especially those in Social Sciences and Humanities, are recommended to equip themselves with generic and transferable skills at the doctoral level (Guerin, 2020; Jackson & Michelson, 2016; Pham, 2023) or enterprise skills (Lean, 2012). There are also recommendations for providing coursework to expand their skill sets (Denicolo, 2003) and substantial resources for them to develop their profiles (Waaijer, 2017).

The above recommendations come from a deficit frame, which views PhD graduates as lacking the required skills to be successful outside academia. It also places a strong emphasis on the responsibilities of individual PhD graduates while overlooking the systemic problem: the neoliberalisation of higher education (Warren, 2017). On the one hand, neoliberalism with its technocratic rationalities drives the process of responsibilising graduates for their employment outcomes (Hooley et al., 2023; Reid & Kelestyn, 2022; Sultana, 2022). On the other hand, it creates competitive and exploitative working conditions in higher education (Guerin, 2020; Khosa et al., 2023, March 23) As a result of neoliberal governance, universities have to adopt corporate management models requiring increased numbers of flexible workers, which accounts for casualisation of the academic workforce and associated job security issues (Warren, 2017). Moreover, the neoliberal funding mechanism has turned universities into exploitative employers by gaining profit from academics’ under-paid work (Bates, 2021).

Following the above line of logic, it makes sense for PhD graduates to leave academia with its poor working conditions and embark on industry-based careers. Nevertheless, a majority of PhD students and graduates in Social Sciences and Humanities want to pursue an academic career, and indicate hope to obtain a permanent academic position (McCarthy & Wienk, 2019; Suomi et al., 2020). These people are portrayed as victims of cruel optimism (Burford, 2018; Guerin, 2020). Specifically, PhD graduates in Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences are reported to hold false hope of obtaining a permanent academic appointment, and be pushed out of academia “by disappointment and inability to remain employed in the sector, rather than being pulled out to better work or lifestyle opportunities” (Guerin, 2020, p. 311). This body of research clearly overlooks PhD graduates’ agentic roles in responding to institutional structures.

PhD graduate agency

There is research acknowledging the role of both individual agency and institutional structures in shaping PhD graduates’ career pathways (Campbell & O’Meara, 2014; O’Meara et al., 2014). While institutions provide career frameworks, comparable to a “road map”, outlining entry and advancement milestones, individuals have agency in navigating their involvement with this “road map” (Dany et al., 2011; Garbe & Duberley, 2021). How individuals navigate their career pathways depends on their interpretation of institutional “career scripts”, which are defined as “collective interpretive schemes” that “represent steps of commonly successful careers in a certain institutional setting” (Laudel et al., 2019, p. 955).

It is important to note that existing research on academic agency mainly drew on the experiences of faculty members who have more or less stable academic positions. There are only a handful of studies discussing the agency of newly graduated PhD holders in managing their careers. For example, Pham et al. (2023) found that international PhD graduates in the Australian context display their agency through drawing on their strengths and multiple identities to obtain employment, and navigating visa requirements. Examining PhD graduates in STEM in the USA, O’Meara et al. (2014) claim that PhD graduates can exercise agency by observing the academic job market and understanding the nature of academic careers. Drawing on the same data set, Campbell and O’Meara (2014) suggest that PhD graduates’ agency can manifest through taking strategic actions to “overcome systemic challenges in order to pursue professional goals” (p. 53). Nevertheless, the question of how PhD graduates in Social Sciences exercise their agency in navigating their career pathways has not been investigated in-depth. By addressing this question, our research can offer sophisticated insights that have implications for enhancing the employment experience of PhD graduates in Social Sciences across individual, institutional, and socio-political levels.

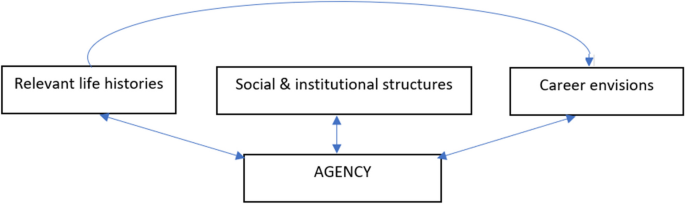

An ecological perspective of agency

In this study, we adopt an ecological perspective of agency, which highlights the interplay between individual capacities and environmental conditions (Priestley et al., 2015). On the one hand, this perspective recognises individual ability to make intentional choices, initiate actions, and exert control over oneself and the environment (Goller & Harteis, 2017). On the other hand, it emphasises how one’s ability to act with agency is afforded by the ecological system within which one operates (Priestley et al., 2015). For example, an academic’s agency is not only facilitated or constrained by socio-political structures and institutional conditions (McAlpine, 2012; Thomas, 2014), but also by their personal histories, and ability to envision different futures (Tao & Gao, 2021). Therefore, to understand PhD graduates’ agency, it is important to take into account their life histories, their career envisions as well as the social structures within which they operate. By exploring not only the social dimension of agency, but also the personal and temporal dimension of agency, this ecological approach can shed light on the multifaceted aspects that shape individuals’ agency in the context of PhD graduate employment. This approach to agency is summarised in the following diagram (Fig. 1):

An ecological perspective on agency (adapted from Priestley et al., 2015)

Research methods

Study design and participants

Our research adopted a qualitative multiple-case study design using semi-structured interviews to explore the employment experiences of PhD graduates in Social Sciences. We interviewed 23 PhD holders who graduated from five Australian universities within 5 years before the interviews. Twenty-one out of 23 participants were from Group of Eight, which are Australia’s leading research-intensive universities. The participants graduated between 2016 and 2021 and aged between 27 and 70. Their research fields cover sociology, education and linguistics. Ethical approval was obtained from Monash University (project ID: 22980).

The interviews, which were conducted in October 2021, focused on their employment experiences and career decisions made before, during and after completion of the PhD. Adopting a semi-structured interviewing approach, we treated each interview as a conversation, giving freedom to the participants to recount their experiences. For example, at the beginning of the interview, we said “please treat me as a friend whom you haven’t seen for a long time. I would love to hear your employment experiences, including before the start of your PhD, during your candidature, and your current position.” The participants would then start telling their stories. Occasionally, where relevant, we would ask them questions, clarifying particular details and aiming to understand why they make particular career decisions.

Analysis approach

Our data analysis comprises two main stages. The first stage involves documenting employment trajectories of each participant while the second stage involves analysis of selective stories representing each employment trajectory. Based on their employment trajectories, we grouped our participants into the following four categories: (1) those who remained in academia and had long-term contracts (1 year or more); (2) who remained in academia and had precarious positions; (3) who moved out of academia; (4) who moved out, and returned to academia. Demographic features of each group provided participants in each category are provided in Table 2:

Although it is tempting to draw conclusions about the association between the demographic features of the group and their employment trajectory, we refrain from doing so due to the small sample size. Instead of reducing our data into numbers, we would like to capture the richness of stories shared by our participants. Though each story is unique in its own way, a common feature emerging among all stories is the participants’ agency in navigating their career pathways.

In this paper, we focus on stories told by four participants who represent four different career pathways. Their stories are chosen not because they are typical of demographic features listed in Table 2. We also do not aim to choose narratives to represent the wide variety of different disciplines within Social Sciences. Instead, we chose these stories because they are the best examples of how PhD graduates can act with agency in navigating each career pathway.

Narrative analysis

Narrative theories have been widely adopted in career development studies, which explore career barriers, adaptability, and decision-making process (Lent, 2016; Meijers & Lengelle, 2012; Rossier et al., 2021). As Rossier et al. (2021) point out, stories allow career counsellors and researchers to understand the dynamic complexity of how individuals navigate moments of vulnerability in their career journeys. Such understanding allows the promotion of individuals’ self-directedness, enabling them to mitigate barriers, cultivate resilience, and foster change (Rossier et al., 2021). Our paper extends this line of research by adopting a narrative approach to examine how PhD graduates navigate the uncertainties of the academic labour market.

We examine each story as a whole as opposed to thematic analysis in which stories are fragmented into thematic categories (Wells, 2011). In our view, a story is not a mere representation of what happens, but rather it is constructed in the process of telling and it is told for social purposes (Ta, 2022; Ta & Filipi, 2020). The construction of stories in narrative research starts at the interview stage: interview questions not only shape the scope of the story to be told, but also influence the development of the story (Stokoe & Edwards, 2006). Stories will then continue to be re-constructed through interpretation and analysis. Acknowledging the constructive nature of telling and re-telling stories, we do not aim to provide an objective account of reality. Instead, we selectively analyse details that help us understand how participants’ agency interplays with other personal and social factors to shape their career pathways.

When analysing stories, we also look at participants’ construction of identity because identity, agency and storytelling have a close-knit relationship (Bamberg et al., 2011; Holland & Lachicotte, 2007). Through telling stories about themselves, “people tell others who they are, but even more important, they tell themselves who they are, and then try to act as though they are who they say they are” (Holland & Lachicotte, 2007, p. 3). In other words, people’s stories about themselves play a role in shaping how they act in certain circumstances (Sfard & Prusak, 2005). Not only participants’ stories about who they are now, but also stories about who they want to become in the future can shape people’s present actions (Sfard & Prusak, 2005). This perspective on storytelling aligns with the ecological approach discussed above, highlighting the interplay between agency and personal histories, future career envisions.

Findings

Staying in academia with a long-term contract

Introduction to Mary

Mary (pseudonym) who completed her doctoral study in 2019 in her late 50s. Prior to her PhD, she was in and out of academia for about 25 years, serving as a sessional staff at a number of universities in Victoria. She also has solid experience in the corporate sector and ran a consultancy business in learning and development for 10 years. Just before the submission of her doctoral thesis, she was offered to work as a full-time research fellow and a deputy director of a centre providing free career consultancy and training for refugees.

An advocate of a good cause

Mary’s career story originated from her years of volunteer work involving supporting refugees. This experience provided her with insights into refugees’ employment issues. Therefore, she wanted to support refugees in career adaptability and decided to do a PhD study in this area. As she told us, her main motivation for her PhD research was to “fill the literature gap and a gap in the sector”. With this claim, Mary displays an image of a passionate scholar who was responding to the call of the industry and the knowledge gap. To realise her aspiration, she strategically recruited supervisors who worked in the field of migration and were able to support her good cause. By making meaningful choices about her research field, and strategically selecting supervisors, Mary displayed her agency in managing the direction of her career pathway.

An independent thinker establishing a niche field

During her PhD candidature, Mary saw herself as building a niche research area, which placed her in a unique position allowing her to function as a bridge between academia and the refugee sector. Besides working on the doctoral thesis, she accumulated extra assets to make her stand out in the job market. For example, she gained substantial industry experience by engaging in voluntary work to support refugees. Moreover, to build up her research experience, she worked as a lead research assistant in four research projects related to refugees’ employment. In this role, she co-wrote grant applications with her supervisors, which in her opinion was an important skill set, giving her an advantage in applying for research jobs.

A versatile leader with a vision

Unlike many PhD candidates struggling to find an academic position, Mary actively shaped her own career pathway and created her own job. Toward the end of her PhD candidature, Mary, together with her ex-supervisor, submitted to his university a proposal to set up a centre for supporting refugees’ employment. This proposal was built around her PhD and other research projects that she and her supervisor had been doing. To manage the centre, she drew on her previous experience running a consultancy business and working for the corporate sector. She saw herself as a multi-tasker with “varied work experience” and “lots of strings” to her bow, which made her a perfect fit for the job. However, she noted that what she is doing is not about creating a job, but instead “it’s about building a reputation, it’s about building impact.” In summary, she positioned herself as a leader with a vision and motivation for creating something bigger than mere employment for herself.

The interplay between agency, personal histories, career envisions and institutional factors

Mary portrayed herself as a highly capable, multi-tasker leader who had an ethical commitment to pay back to the research participants and a vision to create social impacts. Her unique career pathway was not only shaped by her strong agency, her mature age, her rich industry and research experience, her well-articulated career visions, but also influenced by institutional factors, particularly her ex-supervisor and his university. As a senior academic in a leadership position, he supported her in proposing the establishment of the centre. Additionally, she also received strong support from the university with a tradition of running humanitarian centres: it accepted their proposal, created favourable conditions for them to run the centre, and offered her a research fellow position. However, it is noted that these favourable conditions did not come on their own, but Mary played a significant role in creating them: she made serious investigations when choosing an institution and she interviewed several potential supervisors before making a decision. She also deliberately built both industry and research experiences that aligned with her career goal. As a result, she did not struggle to secure a position, but proactively created her own position as the deputy director of a university-based career clinic for refugees even before the completion of her PhD. In short, her agency was a prominent factor that shaped her career pathway.

Staying in academia with precarious positions

Introduction to Kate

Kate (pseudonym), a female domestic graduate in her 40s, is a typical example of a PhD graduate who remained in academia yet struggled to obtain a secure position. Prior to her PhD, she worked as a schoolteacher and was involved in a government project to implement e-learning in schools. She remained in these jobs while enrolling in the PhD program part-time. In the latter half of her PhD candidature, she started to work as a teaching associate at her university. Upon completion of her PhD, she mainly worked as a sessional staff at the same university for over 4 years. At the point of the interview, she got a 5-month contract as an education-focused lecturer at another university and was still looking for a long-term position.

An educator passionate about both research and teaching

Kate’s enrolment in the PhD program came out of her “fascination and respect for higher learning”. She loved “the intellectual enrichment and cultural enrichment of university life”, which she found stimulating. In terms of career considerations, Kate recalled that she had an “internal calling” of conducting research and teaching at university during her PhD candidature. At some point, she expressed her preference of becoming an academic to a professional job, and the “secret desire” to gain “recognition from academia”. However, Kate maintained both jobs as a schoolteacher and a university tutor even after she graduated. Her diverse interests led to her uncertainty about her career pathway: “I get torn between the two pathways [being a teacher and a researcher].” After the completion of her PhD program, she decided to negotiate with her school to have a 6-month agreement after being offered a 1-year contract “just to have a little bit of security before deciding to take the leap into pursuing academia”.

An active job seeker on a million contracts

Kate described herself as very good at networking, which led to several casual contracts after graduation. Her efforts of working hard in her casual roles helped her gain the trust of employers who could provide her with more opportunities. Desperate for a secure position, she actively applied for more stable jobs. She strategically chose to apply for jobs with a similar title or similar role and jobs with employers she had experience working with. In addition, she also tried to make her presence stronger by being around the campus, finding out about and participating in university events, getting herself invited to meetings, and taking advantage of mentoring opportunities offered by the university. Kate displayed her agency in managing her career pathway by making conscious choices regarding job application, networking, and increasing her presence in the university community.

An academic seeing herself as “not an academic yet”

Although Kate worked as a casual academic for several years, she did not “feel like a real academic yet”. She did not feel that she was part of the academic community in her workplace, seeing a clear boundary between those inside and outside the “full-time staff club”. In her words, sessional staff are “not fully embedded in that environment and easily dispensable.” In this claim, Kate highlighted the low status of sessional teacher and implied her aspiration to become an insider of the full-time staff club. To actualise her aspiration, Kate saw the necessity of building a research narrative to showcase her uniqueness through weaving various research experiences she has accumulated into a coherent story. As she believed a strong research narrative is essential for selling oneself in the academic job market, she worked hard to craft one. This story indicates her strong agency in identifying key success factors and working hard to achieve success.

The interplay between agency, personal histories, career envisions, and institutional factors

Kate’s story represents the majority of our participants who worked hard and played agentic roles in navigating their career roadblocks, but still had not been able to obtain a stable academic position. To prepare for an academic career, she accumulated extensive teaching experiences, and built strong connections to academic communities. The missing element, as Kate identified, was a lack of a strong research narrative. Her limitation in research was partly due to the fact that at the early stage of her PhD candidature, she had to take jobs with stable incomes to pay her mortgage and bring up a child as a single mother. As a child grew up, when she felt she could take risks, leaving a stable position as a secondary teacher to engage in various precarious academic jobs. Although her personal circumstances and the institutional requirement regarding research performance have limited her choices at certain points of time, her key career decisions were driven by her aspirations of becoming an academic.

Moving out of academia

Introduction to Noriko

Noriko (pseudonym), a PhD graduate in her late 20s is a typical example of those who moved out of academia and did not intend to return. She started doing her PhD study at a very young age. After her undergraduate degree, she worked at an Australian primary school for a year, and did a Master’s study, which was immediately followed by a PhD study. While doing her Masters’ and PhD studies, she had multiple part-time jobs including teaching at primary schools and tutoring university students. She was actively looking for opportunities to stay in academia, but settled on a full-time professional job as a policy officer at the Department of Education 1 year after her PhD graduation.

A struggling casual teacher with a passion for studying

Noriko experienced multiple struggles when she worked as a casual relief teacher at a primary school. Therefore, she wanted a career change. As a first step, she decided to do a Master’s study, and then a PhD study focusing on relief teaching. She also attributed her decision to her love for studying, which is a common quality that academics tend to share. To fund her PhD research, she actively searched for scholarships, which shows her agentic role in finding opportunities to support her career change.

A strategist building stepping-stones for an academic career

Noriko had multiple casual teaching opportunities during her PhD candidature. Since the middle of her Master’s study, she had already actively searched for opportunities to work as a casual teaching associate, teaching university students. Her strategy was “mass emailing”: she emailed every unit coordinator whom she did not know personally, expressing her interest in teaching their units, which successfully resulted in job offers. In accounting for multiple job opportunities, she highlighted the significance of networking, getting to know people in the faculty, appearing to be competent, and showing initiative when communicating with them. In her own words, she was “open to any opportunities that might arise”, and “strategically took on jobs” that would make her resume look good. This effort led to an offer of a 6-month contract position as a unit coordinator, who is in charge of coordinating teaching staff who teach a subject. In this story, Noriko displayed her agency in creating stepping-stones on the academic pathway, thereby to some extent realising her goal of becoming an academic.

A pragmatist prioritising job security over becoming an academic

Despite the desire to become an academic at the beginning of her PhD candidature, Noriko later realised that it was not realistic to pursue the career. She was also concerned that the pressure in relation to research outputs would drive her life out of balance. Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic experience made her prioritise job security over her ambition to become an academic. When she graduated in 2021, a year after the start of the pandemic, she started looking for a more secure job outside academia. She applied for a position as a policy officer at the Department of Education and performed very well in the interview. She proudly said: “I was really good at showcasing my skills that were translatable to the position […], I remember telling the interviewers, like, I’m really good at synthesising really large volumes of information”. Apparently, Noriko’s decision to leave academia is a rational choice; it was a response to the insecure working conditions; and it was facilitated by her confidence in the transferability of her skills to the non-academic position.

When Noriko received the job offer, she felt like she “finally achieved the goal, which was to get a full-time job”. However, for her, it was also “a bittersweet moment” because it was not an academic job. Despite some “bitterness”, she confessed that she did not want to come back to academia unless “there is, by some miracle, a permanent full-time position”. Job security was the key consideration in her decision of whether or not she would return to academia.

The interplay between agency, personal histories, career envisions, and institutional factors

Noriko’s stories represent a proportion of PhD graduates who had a strong passion for chosen research topics, and acted with agency in pursuing an academic career, but decided to leave academia for job security reasons. In comparison to others who left academia after a number of years, Noriko decided to leave within a couple of months after graduation. This early decision might be attributed to her employment experience as a relief teacher and the COVID-19. While the life of a relief teacher taught her to appreciate stability, the strike of COVID-19 on higher education made her realise how insecure an academic career can be (Hadjisolomou et al., 2022). Her aspiration of becoming an academic became weak and having a stable job became the ultimate goal. However, her decision to leave academia should not be seen as a failure. Rather it is a story of success in which Noriko demonstrated her agency in prioritising what was important to her and taking actions that lead to the achievement of her goal to get a full-time job in an area where her experiences and skills are valued.

Moving out and returning to academia

Introduction to Jack

Jack (pseudonym), a PhD graduate in late 20s, represents those whose career pathways involve multiple turns and twists. After his first degree, he worked in public service in the Australian government for 2 years, before pursuing his PhD degree in Applied Linguistics. During his PhD candidature, he had multiple precarious teaching, marking and research jobs. After the submission of his PhD thesis, he started to look for a lecturer or postdoc position both inside and outside of Australia. However, after a few unsuccessful attempts, he decided to return to the public sector. Nevertheless, a couple of months later, he again resigned from the government job to work as a research officer at a university. At the time of the interview, 6 months after the conferral of his PhD, he was offered a fixed-term postdoctoral position in New Zealand.

An idealist following a dream

Jack developed an interest in a research degree when he was doing a research component for his Honour degree. He envisaged an ideal image of a PhD student and desired to become a research student. This outlook played a critical role in his later decision to pursue an academic career; however, after his BA Honour degree, he decided to take a job in public service for financial reasons. In this position, Jack always felt “unfulfilled”. After meeting his partner who was doing a PhD degree, his dream of becoming a PhD student became stronger: “When I saw what my partner’s life was like I thought, wow, it looks so nice”. Holding an idealised notion of a PhD student’s life working 9–5 in a supportive environment, Jack decided to apply for PhD scholarships. He admitted that he chose the research topic because of his personal interest without considering whether his topic choice could bring about opportunities for an academic career. His decision-making was clearly driven by his love for research and the idealistic perspective of a PhD student’s life.

A dreamer facing a reality check

Once being a PhD student, Jack’s dream to become an academic grew stronger. To pave the road for his academic career, he sought to obtain teaching and research experiences, and actively participate in multiple research communities at his university. He secured multiple precarious jobs including tutoring and marking a couple of subjects. Around the time of thesis submission, he started to look for but failed to gain a postdoc position. Despite his proactive measures in preparing for an academic career, he did not succeed in obtaining an academic position. He attributed this lack of success to his limited publications. Although he still longed for academic life, he decided to move back to the public sector working as a policy officer, for financial reasons as he acknowledged “I needed something when the scholarship money ran out”.

A persistent pursuer of an academic career

While working in the public service sector, Jack still persistently pursued his academic dream, spending his spare time on publications, thus developing his academic profile. Despite his fear of being unable to get an on-going academic job, he made a hard decision: leaving the stable job to seek career fulfilment. Here is what he told us about why he left: “If I don’t get an academic job within one year or two years, then it's kind of over for me like I won't be able to get into the area. So, I was really freaking out, I quit”. His words show his strong desire to get back to academia and his awareness of the time pressure, which both account for his decision to return to academia. After leaving the government job, Jack actively searched for better jobs while working on publications. He looked for positions in China, the UK, and Europe and succeeded with a postdoctoral application with the Chinese government. Nevertheless, he did not go to China for various reasons including his unfamiliarity with the Chinese academic environment, and the uncertainty of getting back to Australia.

A semi-happy postdoctoral fellow

After resigning from the government position, Jack got a job as a research officer at a university. Although he found the position more exciting than the government job, he sometimes felt frustrated with the situation that he had to support other researchers when he could not be one himself. Therefore, he sent another application and succeeded in obtaining a postdoctoral fellow position in New Zealand. He was happy with the job offer except for one thing: he had to relocate to New Zealand. However, he thought moving to New Zealand was a stepping-stone for him to get back to an academic career in Australia. This decision was driven by his long-term goal of having an academic career in Australia. Despite the happy moments of having a fixed-term contract, he was still concerned about its temporary nature.

The interplay between agency, personal histories, career envisions, and institutional factors

Jack was the only participant who went back and forth several times between academic and non-academic employment. Fuelled by his envision for an ideal life of an academic, he proactively participated in research communities, and searched for opportunities that can lead to an academic career, which showed his strong agency in navigating his career. Like other participants, the key barrier for him to obtain a stable academic position is the institutional requirement regarding research output. Also like others, he had to prioritise financial security at some stages; however, he did return to academia accepting a less stable position in a neighbouring country, viewing it as a ticket for his entry into a stable academic position in Australia in the future. The fact that he was a young male with no childcare responsibilities might have made it easier for him to accept certain instability in the pursuit of an academic career.

Discussions

This study explored how PhD graduates in Social Sciences navigated their careers in a tight labour market for academic positions. It unpacked the role of agency, personal histories, career envisions and institutional factors in shaping four typical career trajectories: (1) remaining in academia with long-term contracts; (2) remaining in academia with casual or short-term contracts; (3) leaving academia; and (4) leaving and returning to academia. Analysis of stories from these four career trajectories highlighted PhD graduates’ agency as the key link among various factors contributing to shaping the trajectories.

There are multiple factors accounting for why individuals remained in academia. For Mary, who remained in academia with a stable position, supportive factors include her mature age, strong agency in creating career opportunities, well-formed career vision, extensive industry experience, solid connections with the industry, and institutional support. Some of these factors are though observed in the case of Kate, who landed in a short-term contract academic position after graduation. They include her strong aspiration for an academic career, industry experiences, and academic connections, which were also present in the story of Jack, who returned to academia after some diversions. A supportive factor that other participants did not share with Jack was his status as a young male, which allowed him to accept certain instability in his pursuit of an academic career.

The main barrier in most participants’ pursuits of an academic career was regarding research output. According to Kate and Jack, the major hindrance for them to obtain an on-going academic position was their lack of strong research narratives and track records. Likewise, due to the pressures related to research output, Noriko gave up pursuing an academic career. Research output pressure is a long-existing institutional problem. In the neoliberal higher education, to compete for research funding and high ranking, universities have widely adopted recruitment and reward systems that favour academics with high research output (Bogt & Scapens, 2012; Douglas, 2013). These systems apparently disadvantage newly graduated PhD holders, prolonging the time for them to find a stable position (Nadolny & Ryan, 2015). Moreover, an overemphasis on research output is reported to create stress, and work-life balance issues (Culpepper et al., 2020; Szelényi & Denson, 2019), which account for an increasing rate of PhD graduates choosing non-academic careers (Feldon et al., 2023).

A common factor that drew our participants away from academia is financial security. For financial reasons, Kate was unable to devote her time to research and publication, and Jack had to leave academia several times to earn a living elsewhere regardless of their strong passion for research. For financial security, Noriko accepted a professional job albeit feeling sad about giving up an academic career. Job security, which is associated with the casualisation in academia in countries with developed research systems, has become a significant concern for PhD graduates, causing various well-being issues such as stress and anxiety (Van Benthem et al., 2020). More importantly, high casualisation can potentially de-professionalise academic work, erode academic freedom and hence make academia less attractive to PhD graduates (Kimber & Ehrich, 2015; Ryan et al., 2017).

Regardless of the above challenges, a considerable portion of our participants strongly held on to their aspiration to an academic career (16 out of 23). For some participants, their motivation was fuelled by an idealised image of academic life. However, they are not naïve victims of “cruel optimism” as portrayed in some literature (Bieber & Worley, 2006; Guerin, 2020). Instead, they were well aware of the challenges associated, knew what they would need to do to succeed, and deliberately took actions to achieve their goals. To name a few examples, Mary established a niche area where she can translate her research into practice. Kate worked on crafting a research narrative to promote her research visions. Jack explored and succeeded in obtaining opportunities overseas. Noriko knew how to sell herself to non-academic recruiters and was successful in applying her research capabilities to her professional work. In short, they displayed strong agency in responding to the challenges as well as opportunities in their career pathways: they decided what career they wanted to have, and how to achieve their career goals. Their stories all highlight the importance of agency in shaping one’s career trajectories, which is consistent with existing research (Campbell & O’Meara, 2014; O’Meara et al., 2014).

Implications for PhD students and graduates

The above findings offer practical implications for PhD students and graduates. PhD graduates should be aware that they can enact their agency in making career choices and responding to the institutional pressures proactively (Campbell & O’Meara, 2014; O’Meara et al., 2014). To make well-informed career decisions, they need to know career options both inside and outside the academic sector. If they prefer to stay in academia, it is important to be aware that passions, industry experiences, and networking are necessary, but not sufficient to obtain a tenured position in academia. Similarly, research output is an essential factor, but focussing on the number of publications only is not sufficient either. The key element seems to be the ability to construct a narrative that helps present oneself as a researcher with a strong potential to make unique contributions and create lasting impacts as narrative has been increasingly used as a tool in performance measurement in higher education (Bandola-Gill & Smith, 2022; Chubb & Reed, 2018).

Implications for PhD supervisors, universities and industry employers

Our research calls for institutional recognition of PhD students’ agency. Universities can support this by providing resources and opportunities (e.g. in the form of funding) for them to “start up” their research career (O’Meara et al., 2014). In addition, as people who know their students’ research fields, supervisors can act as mentors during their career building-up journey. Instead of merely focusing on the particularities of the PhD research, supervisors can invest time and effort in supporting students to form a career vision and identify competitive edges. Mentoring practices, which have been adopted in PhD programs in STEM, (Curtin et al., 2016; Hund et al., 2018), can also be offered to those in Social Sciences.

For students who do not intend to pursue an academic career, universities can support their agency by legitimising non-academic careers and integrating career development with research training (Universities Australia, 2013). More importantly, a shift in perspective is timely required: PhD students should be treated as highly capable individuals instead of a labour force lacking industry-relevant skills (e.g., Jackson & Michelson, 2016; Pham, 2023). Appreciating PhD students’ agency, universities can support PhD students to reach their full potential while a deficit perspective may result in a waste of resources in running skills development programmes that do not meet student needs (Moreno, 2014). In the same vein, with an agency-focused perspective, industry employers can appreciate the broader value of PhD graduates’ skills in enhancing the growth of their organisations (McAlpine & Inouye, 2022).

Policy implications

Policymakers also need to consider the agency of PhD students and graduates, treating them as valued brokers in the process of translating advanced knowledge for the benefit of the society at large (Lazurko et al., 2020), instead of turning them into fierce competitors for limited research funding and academic appointments (Carson et al., 2013; Pelletier et al., 2019). Under the current funding systems, and the casualisation of academic workforce, working conditions in academia have become increasingly competitive, which is associated with early career academics’ mental health issues (Culpepper et al., 2020; Szelényi & Denson, 2019). To address these issues, there are calls for increasing on-going positions (NTEU, 2020), strengthening support for early-career researchers (McComb et al., 2021), and reforming research funding policies (O’Kane, 2023). Taking the Australian system for example, funding increases in line with PhD completion, which accounts for a surplus supply of PhD graduates compared to the availability of academic positions (Hoang et al., 2023, May 18). To address this issue, reducing PhD enrolments in Social sciences has been recommended as a solution (Croucher, 2016, November 18). This recommendation may help resolve the supply–demand issue, but would lead to the shrinking of social research, which would have detrimental impacts on the society at large (Shaw, 2023, July 25). Instead of limiting PhD enrolments, measures should be taken to promote employment of PhD graduates in the translation of social research findings into practice.

Conclusion and limitation

In this paper, we provide narrative evidence to illustrate the agency of Social Sciences PhD graduates in navigating their career pathways. By emphasising their agentic roles, we are able to identify the key institutional and personal factors that bear strong consequences on the twists and turns in their career pathways. Based on our analysis of the stories told by our participants, we offer recommendations for practice and policy. It is important to note that the stories may not be representative of all social research disciplines due to the limitation in sampling: the majority of our participants did their PhD study in linguistics and education.

References

Auriol, L. (2010). Careers of doctorate holders: Employment and mobility patterns. OECD Science, Technology and Industry. https://doi.org/10.1787/5kmh8phxvvf5-en

Auriol, L., Misu, M., & Freeman, R. A. (2013). Careers of doctoral holders: Analysis of labour market and mobility indicators. OECD Science, Technology and Industry Working Papers. No. 2013/04. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/5k43nxgs289w-en

Bamberg, M., De Fina, A., & Schiffrin, D. (2011). Discourse and identity construction. In S. Schwartz, K. Luyckx, & V. L. Vigoles (Eds.), Handbook of Identity Theory and Research (pp. 177–199). Springer.

Bandola-Gill, J., & Smith, K. E. (2022). Governing by narratives: REF impact case studies and restrictive storytelling in performance measurement. Studies in Higher Education, 47(9), 1857–1871. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2021.1978965

Bates, D. (2021). Academic labor and its exploitation. Theory & Event, 24(4), 1090–1109. https://doi.org/10.1353/tae.2021.0060

Bennett, D., Roberts, L., Ananthram, S., & Broughton, M. (2018). What is required to develop career pathways for teaching academics? Higher Education, 75(2), 271–286. https://link.springer.com/article/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-017-0138-9

Bieber, J. P., & Worley, L. K. (2006). Conceptualizing the academic life: Graduate students’ perspectives. The Journal of Higher Education, 77(6), 1009–1035. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2006.11778954

Bogt, H. J., & Scapens, R. W. (2012). Performance management in universities: Effects of the transition to more quantitative measurement systems. European Accounting Review, 21(3), 451–497. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638180.2012.668323

Boulos, A. (2016). The labour market relevance of PhDs: An issue for academic research and policy-makers. Studies in Higher Education, 41(5), 901–913. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2016.1147719

Buenstorf, G., Koenig, J., & Otto, A. (2023). Expansion of doctoral training and doctorate recipients’ labour market outcomes: Evidence from German register data. Studies in Higher Education, 48(8), 1216–1242. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2023.2188397

Burford, J. (2018). The trouble with doctoral aspiration now. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 31(6), 487–503. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2017.1422287

Campbell, C. M., & O’Meara, K. (2014). Faculty agency: Departmental contexts that matter in faculty careers. Research in Higher Education, 55(1), 49–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-013-9303-x

Carson, L., Bartneck, C., & Voges, K. (2013). Over-competitiveness in academia: A literature review. Disruptive Science and Technology, 1(4), 183–190. https://doi.org/10.1089/dst.2013.0013

Chubb, J., & Reed, M. S. (2018). The politics of research impact: Academic perceptions of the implications for research funding, motivation and quality. British Politics, 13(3), 295–311. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41293-018-0077-9

Couston, A., & Pignatel, I. (2018). PhDs in business: Nonsense, or opportunity for both? Global Business and Organizational Excellence, 37(2), 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1002/joe.21842

Crimmins, G. (2017). Feedback from the coal-face: How the lived experience of women casual academics can inform human resources and academic development policy and practice. International Journal for Academic Development, 22(1), 7–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2016.1261353

Croucher, G. (2016). It’s time to reduce the number of PhD students, or rethink how doctoral programs work. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/its-time-to-reduce-the-number-of-phd-students-or-rethink-how-doctoral-programs-work-68972

Croucher, G. (2023). Three decades of change in Australia’s university workforce. Melbourne Centre for the Study of Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.26188/23995704

Culpepper, D., Lennartz, C., O’Meara, K., & Kuvaeva, A. (2020). Who gets to have a life? Agency in work-life balance for single faculty. Equity & Excellence in Education, 53(4), 531–550. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2020.1791280

Curtin, N., Malley, J., & Stewart, A. J. (2016). Mentoring the next generation of faculty: Supporting academic career aspirations among doctoral students. Research in Higher Education, 57(6), 714–738. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-015-9403-x

Dany, F., Louvel, S., & Valette, A. (2011). Academic careers: The limits of the ‘boundaryless approach’ and the power of promotion scripts. Human Relations, 64(7), 971–996. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726710393537

Denicolo, P. (2003). Assessing the PhD: A constructive view of criteria. Quality Assurance in Education, 11(2), 84–91. https://doi.org/10.1108/09684880310471506

Douglas, A. S. (2013). Advice from the professors in a university social sciences department on the teaching-research nexus. Teaching in Higher Education, 18(4), 377–388. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2012.752727

Feder, T. (2018). Contract lecturers are a growing yet precarious population in higher education. Physics Today, 71(11), 22–23. https://doi.org/10.1063/PT.3.4065

Feldon, D. F., Wofford, A. M., & Blaney, J. M. (2023). In L. W. Perna (Ed.), Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research (pp. 325–414). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-94844-3_4-1

Garbe, E., & Duberley, J. (2021). How careers change: Understanding the role of structure and agency in career change. The case of the humanitarian sector. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 32(11), 2468–2492. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2019.1588345

Germain-Alamartine, E., Ahoba-Sam, R., Moghadam-Saman, S., & Evers, G. (2021). Doctoral graduates’ transition to industry: Networks as a mechanism? Cases from Norway, Sweden and the UK. Studies in Higher Education, 46(12), 2680–2695. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1754783

Goller, M., & Harteis, C. (2017). Human agency at work: Towards a clarification and operationalisation of the concept. In M. Goller & S. Paloniemi (Eds.), Agency at work: An agentic perspective on professional learning and development (pp. 85–103). Springer International Publishing.

Guerin, C. (2020). Stories of moving on HASS PhD graduates’ motivations and career trajectories inside and beyond academia. Arts and Humanities in Higher Education, 19(3), 304–324. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474022219834448

Hadjisolomou, A., Mitsakis, F., & Gary, S. (2022). Too scared to go sick: Precarious academic work and ‘Presenteeism Culture’ in the UK higher education sector during the Covid-19 pandemic. Work, Employment and Society, 36(3), 569–579. https://doi.org/10.1177/09500170211050501

Hancock, S. (2023). Knowledge or science-based economy? The employment of UK PhD graduates in research roles beyond academia. Studies in Higher Education, 48(10), 1523–1537. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2023.2249023

Hayter, C., & Parker, M. (2019). Factors that influence the transition of university postdocs to non-academic scientific careers: An exploratory study. Research Policy, 48(3), 556–570. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2018.09.009

Hoang, S., Ta, B. T., Khong, H., & Dang, T. (2023). Australia has way more PhD graduates than academic jobs. Here’s how to rethink doctoral degrees. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/australia-has-way-more-phd-graduates-than-academic-jobs-heres-how-to-rethink-doctoral-degrees-203057

Holland, D., & Lachicotte, W. (2007). Vygotsky, Mead, and the new sociocultural studies of identity. In H. Daniels, M. Cole, & J. Wertsch (Eds.), The Cambridge companion to Vygotsky (pp. 101–135). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CCOL0521831040.005

Hooley, T. J., Bennett, D., & Knight, E. B. (2023). Rationalities that underpin employability provision in higher education across eight countries. Higher Education, 86(5), 1003–1023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00957-y

Hund, A. K., Churchill, A. C., Faist, A. M., Havrilla, C. A., Love Stowell, S. M., McCreery, H. F., ..., & Scordato, E. S. (2018). Transforming mentorship in STEM by training scientists to be better leaders. Ecology and Evolution, 8(20), 9962–9974. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2011.01717.x

Jackson, D., & Michelson, G. (2016). PhD-educated employees and the development of generic skills. Australian Bulletin of Labour, 42(1), 108–134. https://search.informit.org/doi/https://doi.org/10.3316/ielapa.439531603235277

Khosa, A., Ozdil, E., & Burch, S. (2023). 'Some of them do treat you like an idiot’: What it’s like to be a casual academic. The Conversation. http://theconversation.com/some-of-them-do-treat-you-like-an-idiot-what-its-like-to-be-a-casual-academic-201470

Kimber, M., & Ehrich, L. C. (2015). Are Australia’s universities in deficit? A tale of generic managers, audit culture and casualisation. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 37(1), 83–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2014.991535

Lama, T. M., & Joullié, J. (2015). Casualization of academics in the Australian higher education: Is teaching quality at risk?. Research in Higher Education Journal, 28, 11. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1062094.pdf

Laudel, G., Bielick, J., & Gläser, J. (2019). “Ultimately the question always is: “What do I have to do to do it right?”’Scripts as explanatory factors of career decisions. Human Relations, 72(5), 932–961. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726718786550

Lazurko, A., Alamenciak, T., Hill, L. S., Muhl, E.-K., Osei, A. K., Pomezanski, D., ..., Sharmin, D. F. (2020). What will a PhD look like in the F=future? Perspectives on emerging trends in sustainability doctoral programs in a time of disruption. World Futures Review, 12(4), 369–384. https://doi.org/10.1177/1946756720976710

Lean, J. (2012). Preparing for an uncertain future: The enterprising PhD student. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 19(3), 532–548. https://doi.org/10.1108/14626001211250261

Lent, R. W. (2016). Self-efficacy in a relational world: Social cognitive mechanisms of adaptation and development. The Counseling Psychologist, 44, 573–594. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000016638742

Marini, G. (2022). The employment destination of PhD-holders in Italy: Non-academic funded projects as drivers of successful segmentation. European Journal of Education, 57(2), 289–305. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12495

McAlpine, L., & Inouye, K. (2022). What value do PhD graduates offer? An organizational case study. Higher Education Research & Development, 41(5), 1648–1663. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2021.1945546

McAlpine, L., Amundsen, C., & Turner, G. (2013). Constructing post-PhD careers: Negotiating opportunities and personal goals. International Journal for Researcher Development, 4(1), 39–54. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRD-01-2013-0002

McAlpine, L. (2012). Identity-trajectories: Doctoral journeys from past to present to future. Australian Universities’ Review, 54(1), 38–46. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ968518.pdf

McCarthy, O. X., & Wienk, D. M. (2019). Who are the top PhD employers? AMSI (Australian Mathematical Sciences Institute and CSIRO (Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research). https://amsi.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/advancing_australias_knowledge_economy.pdf

McComb, V., Eather, N., & Imig, S. (2021). Casual academic staff experiences in higher education: Insights for academic development. International Journal for Academic Development, 26(1), 95–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2020.1827259

Meijers, F., & Lengelle, R. (2012). Narratives at work: The development of career identity. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 40(2), 157–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2012.665159

Menard, C. B., & Shinton, S. (2022). The career paths of researchers in long-term employment on short-term contracts: Case study from a UK university. PLoS One, 17(9), e0274486. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274486

Moreno, R. (2014). Management of the level of coursework in PhD education: A case of Sweden. Journal of Applied Economics and Business Research, 4(3), 168–178.

Nadolny, A., & Ryan, S. (2015). McUniversities revisited: A comparison of university and McDonald’s casual employee experiences in Australia. Studies in Higher Education, 40(1), 142–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2013.818642

NTEU. (2020). The growth of insecure employment in higher education. Nation Tertiary Education Unition. https://www.pc.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0012/337998/sub036-productivity-attachmentb.pdf

O’Kane, M. (2023). Australian universities accord interim report. Australian Government: Department of Education. https://www.education.gov.au/australian-universities-accord/resources/accord-interim-report

O’Meara, K., Jaeger, A., Eliason, J., Grantham, A., Cowdery, K., Mitchall, A., & Zhang, K. (2014). By design: How departments influence graduate student agency in career advancement. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 9(1), 155–179. https://ijds.org/Volume9/IJDSv9p155-179OMeara0518.pdf

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). (2021). Reducing the precarity of academic research careers. OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers, No. 113. https://doi.org/10.1787/23074957

Pelletier, K. L., Kottke, J. L., & Sirotnik, B. W. (2019). The toxic triangle in academia: A case analysis of the emergence and manifestation of toxicity in a public university. Leadership (London, England), 15(4), 405–432. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742715018773828

Pham, T., Dai, K., & Saito, E. (2023). Forms of agency enacted by international Ph.D. holders in Australia and Ph.D. returnees in China to negotiate employability. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2023.2237885

Pham, T. (2023). What really contributes to employability of PhD graduates in uncertain labour markets?. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2023.2192908

Priestley, M., Biesta, G., & Robinson, S. (2015). Teacher agency: An ecological approach. Bloomsbury.

Reid, E. R., & Kelestyn, B. (2022). Problem representations of employability in higher education: Using design thinking and critical analysis as tools for social justice in careers education. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 50(4), 631–646. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2022.2054943

Rogers, B., & Swain, K. (2022). Teaching academics in higher education: Resisting teaching at the expense of research. The Australian Educational Researcher, 49(5), 1045–1061. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-021-00465-5

Rossier, J., Cardoso, P. M., & Duarte, M. E. (2021). The narrative turn in career development theories: An integrative perspective. In P. J. Robertson, T. Hooley, & P. McCash (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Career Development, 169–180. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190069704.013.13

Ryan, S., Connell, J., & Burgess, J. (2017). Casual academics: A new public management paradox. Labour & Industry, 27(1), 56–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/10301763.2017.1317707

Sfard, A., & Prusak, A. (2005). Telling identities: In search of an analytic tool for investigating learning as a culturally shaped activity. Educational Researcher, 34(4), 14–22. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X034004014

Shaw, R. (2023). A changing world needs arts and social science graduates more than ever – Just ask business leaders. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/a-changing-world-needs-arts-and-social-science-graduates-more-than-ever-just-ask-business-leaders-210194

Spina, N., Smithers, K., Harris, J., & Mewburn, I. (2022). Back to zero? Precarious employment in academia amongst ‘older’ early career researchers, a life-course approach. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 43(4), 534–549. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2022.2057925

Stokoe, E., & Edwards, D. (2006). Story formulations in talk-in-interaction. Narrative Inquiry, 16(1), 56–65. https://doi.org/10.1075/ni.16.1.09sto

Sultana, R. G. (2022). Four ‘dirty words’ in career guidance: From common sense to good sense. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-022-09550-2

Suomi, K., Kuoppakangas, P., Kivistö, J., Stenvall, J., & Pekkola, E. (2020). Exploring doctorate holders’ perceptions of the non-academic labour market and reputational problems they relate to their employment. Tertiary Education and Management, 26, 397–414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11233-020-09061-1

Szelényi, K., & Denson, N. (2019). Personal and institutional predictors of work-life balance among women and men faculty of color. The Review of Higher Education, 43(2), 633–665. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/743033

Ta, B. T., & Filipi, A. (2020). Storytelling as a resource for pursuing understanding and agreement in doctoral research supervision meetings. Journal of Pragmatics, 165, 4–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2020.03.008

Ta, B. T. (2022). Giving advice through telling hypothetical stories in doctoral supervision meetings. In A. Filipi, B. T. Ta, & M. Theobald (Eds.), Storytelling Practices in Home and Educational Contexts: Perspectives from Conversation Analysis (pp. 311–334). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-9955-9_16

Tao, J., & Gao, X. S. (2021). Language teacher agency. Cambridge University Press.

Thomas, L. D. (2014). Identity-trajectory as a theoretical framework in engineering education research. 2014 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition. https://peer.asee.org/identity-trajectory-as-a-theoretical-framework-in-engineering-education-research

Universities Australia. (2013). A smarter Australia: An agenda for Australian higher education 2013–2016. https://apo.org.au/node/32987.

Van Benthem, K., Adi, M. N., Corkery, C. T., Inoue, J., & Jadavji, N. M. (2020). The changing postdoc and key predictors of satisfaction with professional training. Studies in Graduate and Postdoctoral Education, 11(1), 123–142. https://doi.org/10.1108/SGPE-06-2019-0055

Waaijer, C. J. F. (2017). Perceived career prospects and their influence on the sector of employment of recent PhD graduates. Science and Public Policy, 44(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scw007

Warren, S. (2017). Struggling for visibility in higher education: Caught between neoliberalism ‘out there’and ‘in here’–an autoethnographic account. Journal of Education Policy, 32(2), 127–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2016.1252062

Wells, K. (2011). Narrative inquiry. Oxford University Press.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ta, B., Hoang, C., Khong, H. et al. Australian PhD graduates’ agency in navigating their career pathways: stories from social sciences. High Educ (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-024-01181-6

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-024-01181-6