Abstract

Entrepreneurial alertness (EA) research has made substantial progress in identifying the psychological and organizational antecedents and consequences of EA. However, the interactions between environmental factors and EA are understudied and it is unclear how alertness influences and is shaped by entrepreneurs’ local ecosystems. In this “perspectives” essay, we contend that EA and entrepreneurial ecosystems research could be enriched by greater cross-fertilization. We respond to calls for more focus on the microfoundations of entrepreneurship by exploring the opportunities in research at the interface of EA and entrepreneurial ecosystems. We develop a multi-level framework to explain how EA is not only influenced by entrepreneurial ecosystems but can collectively influence the system-level functioning and leadership of ecosystems. Our framework clarifies how EA is shaped by the social, cultural, and material attributes of ecosystems and, in turn, how EA influences ecosystem attributes (diversity and coherence) and outcomes (resilience and coordination). We explain why it is critical to treat the environment as more than simply a moderating influence on the effects of EA and why it is fruitful for entrepreneurship research to develop a fuller picture of EA’s contextual determinants and outcomes. We conclude by proposing a research agenda that explores the interplay between EA and entrepreneurial ecosystems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Entrepreneurial ecosystems are the interdependent communities of local actors, forces, and places that support entrepreneurship (Stam, 2015; Wurth et al., 2022). Entrepreneurial ecosystems research builds on the contextual turn in entrepreneurship, which emphasizes that entrepreneurial activity does not occur in a vacuum; entrepreneurs pursue opportunities in distinct contexts and their local environments consist of complex sets of location-specific and place-based factors (Welter et al., 2019; Welter & Baker, 2021). Entrepreneurial ecosystems research extends work on industrial clusters, innovation systems, and entrepreneurial communities, which is focused on the geography of entrepreneurship and innovation, by placing the entrepreneur at the center of analysis (Acs et al., 2017).

Entrepreneurial ecosystems scholars have sought to explain why some cities, regions, and nations are more fertile environments for entrepreneurs and better equipped to support entrepreneurship than other locations because of geographic differences in their characteristics and resources (e.g., Audretsch & Belitski, 2021; Kapturkiewicz, 2022). Variation in entrepreneurial ecosystems depends on differences in their social, cultural, and material attributes (Spigel, 2017). Differences in these attributes reflect that places differ in their local networks, physical infrastructure (e.g., meeting spaces), support organizations (e.g., incubators, accelerators), historical development, cultures, and the availability of financial capital (Loots et al., 2021; Spigel, 2017). The components of entrepreneurial ecosystems and how their attributes are coordinated create meaningful variation in the vitality and functioning of ecosystems and, ultimately, in their ability to enable entrepreneurship (Spigel & Harrison, 2018). For instance, studies have explored the implications of the distinct configurations of entrepreneurial ecosystems in the Asia Pacific context, including cities and regions in Malaysia (Harrison et al., 2018), China (Wang et al., 2022), India (Mani, 2021), and Singapore (Kim et al., 2020). However, while macro-oriented entrepreneurship research has made the system-level emergence, elements, and functioning of ecosystems increasingly clear, the microfoundations of entrepreneurial ecosystems remain understudied (Roundy & Lyons, 2023). Research has devoted limited attention to how the attributes of entrepreneurs, such as their cognitive characteristics, are shaped by the attributes of their local ecosystems and, in turn, influence the functioning of entrepreneurial ecosystems (Roundy & Lyons, 2023; Wurth et al., 2022).

Entrepreneurial alertness (EA) is a fundamental characteristic of entrepreneurs. As a cognitive construct (Tang et al., 2012), EA is a psychological foundation of entrepreneurial behavior and a “core component” of “opportunity recognition, evaluation, and exploitation” (Levasseur et al., 2022; Tang et al., 2021b: 2). EA plays a vital role in the creation and discovery paradigms of opportunity pursuit (Lanivich et al., 2022) and is conceptualized as a schema that allows some individuals to identify entrepreneurial opportunities (Pidduck et al., 2020; Valliere, 2013).

Despite the substantial progress of EA research in the past decade, there remain “numerous unexplored research opportunities relating to the antecedents and consequences of EA” and research is particularly needed that examines the “validity of EA conceptualization and operationalization in different sub-contexts” (Tang et al., 2022; emphasis added). Although research has isolated several key predictors and outcomes of EA, scholars have emphasized the determinants and effects of EA at individual and organizational levels (Chavoushi et al., 2021; Sharma, 2019). The intersection of macro-environmental factors and micro-psychological attributes, like EA, has received significantly less attention (Yang et al., 2023).

The role of context in alertness is understudied because EA research often treats context as a generic concept (“the environment”) or as simply the source of economic disruptions and signals, which trigger entrepreneurial cognitions and create the potential for opportunities (e.g., Roundy, Harrison, Khavul, Perez-Nordvedt, & McGee, 2018b). The generic conceptualization of entrepreneurs’ contexts is partly attributable to Kirzner’s (1973, 1979) early theorizing that focused on “market alertness”—i.e., entrepreneurs responding to external economic incentives in their market environments (Lanivich et al., 2022)—but that did not focus on the contextualized difference in entrepreneurs’ local markets. More recent research about how EA functions has focused on entrepreneurs engaging in “environmental observation” and “environmental awareness” (Lanivich et al., 2022; McCaffrey, 2014). However, entrepreneurs’ environments are rich and variegated contexts that consist of more than economic stimuli.

Entrepreneurial ecosystems research finds that variety in entrepreneurs’ local contexts has important implications for the entrepreneurship process (Wurth et al., 2022). Ecosystems scholars seek to provide a holistic picture of entrepreneurs’ environments that goes beyond financial factors to include the complex set of economic and non-economic forces in the local contexts of entrepreneurs (Stam & Welter, 2021). Entrepreneurial ecosystems play a critical—but sorely understudied—role in EA because they represent the places and spaces in which EA manifests and in which alert entrepreneurs pursue opportunities. Entrepreneurial ecosystems also contain the local resources that alert entrepreneurs use to build new ventures (Spigel & Vinodrai, 2021). Likewise, when individuals exhibit the behaviors associated with EA, such as leveraging their local environments for resources and combining resources into novel business ideas (Lanivich et al., 2022), these entrepreneurial activities have effects that extend beyond venture boundaries. In the aggregate, the entrepreneurial activities inspired by EA change the complexion of the local entrepreneurial ecosystems in which they take place.

Because of the powerful interplay between entrepreneurial cognition and context, in this “perspectives” essay, we contend that EA and entrepreneurial ecosystems research can be enriched by cross-fertilization between the two areas of inquiry. Specifically, we respond to calls for more research on the microfoundations of entrepreneurship (e.g., Sun et al., 2020) by identifying the opportunities at the intersection of EA and entrepreneurial ecosystems and clarifying how the micro-level characteristics of entrepreneurs’ cognition are shaped by and influence their macro-level contexts. In doing so we ask, how is EA shaped by entrepreneurial ecosystems and, in turn, how does EA influence the system-level dynamics of entrepreneurial ecosystems?

To address this two-part question, we develop a multi-level framework that explains how EA is influenced by the attributes of entrepreneurial ecosystems and, collectively, how the alertness of entrepreneurs aggregates to influence the functioning and leadership of entrepreneurial ecosystems. In addition, we propose a research agenda that contributes to work on the “contextual determinants of entrepreneurial cognition and new venture ideation” (Lanivich et al., 2022: 1166). We explain why it is important to treat the environment as more than simply a boundary condition of EA. Ultimately, we seek to develop a fuller picture of EA’s contextual determinants and outcomes by going beyond the view that the environment is principally a source of economic stimuli and by considering how EA interacts with the social, cultural, and material attributes of the contexts of entrepreneurs (Spigel, 2017).

Conceptual foundations

The dimensions of entrepreneurial alertness

EA is commonly conceptualized as involving information scanning and search, information association and connection, and opportunity evaluation and judgment (Tang et al., 2012). A recent review of the EA literature proposed three overarching dimensions (1) observation of the environment, (2) resource association, and (3) idea evaluation (Lanivich et al., 2022).

Observation of the environment means that alert entrepreneurs have senses that are “attentive to external issues” (Lanivich et al., 2022: 1170). This attentiveness involves alert entrepreneurs continually having their “antennas up” and searching for signals of innovative ideas and opportunities (Tang, 2008). The second EA dimension, resource association, involves alert entrepreneurs “making mental connections between resources that induce new venture ideas and subject[ing] further environmental observations to new perspectives wherein the connections exist” (Lanivich et al., 2022: 1170). With this dimension, there is again an emphasis on entrepreneurs working with the observations, information, and resources drawn from their environments and connecting them to formulate new venture ideas. Finally, the “idea evaluation” dimension of EA is the “proactive thought experimentation on resource associations and environmental cues that determine whether they might be worthy of further development (Lanivich et al., 2022: 1170). During idea evaluation, entrepreneurs assess the observations gained from the environment and begin to determine if their ideas are associated with a viable opportunity for a venture that will, ultimately, be created in a specific context. In sum, each of EA’s dimensions is tied to features in entrepreneurs’ environments. But, despite the crucial role of environments in EA, research is needed that creates a more granular understanding of how environmental contexts influence EA.

The environments of entrepreneurs

The unique environments of entrepreneurs influence the entrepreneurship process and its outcomes (e.g., Bruton et al., 2015). Entrepreneurial ecosystems are a major component of the local environments that alert entrepreneurs observe and scan. Although entrepreneurs can receive information and resources from both local and non-local sources, entrepreneurial ecosystems represent entrepreneurs’ immediate contexts, which are rich sources of environmental cues. Alert entrepreneurs’ senses are engaged with what is happening in their ecosystems and attuned to the external issues that local ecosystems present. As explained in the sections that follow, entrepreneurial ecosystems are the source of a variety of resources, which can stimulate new venture ideas and opportunities. If entrepreneurs are alert to their local startup communities, their entrepreneurial ecosystems can assist them in connecting to the resources in their immediate environments and assessing if the new venture ideas tied to these connections represent opportunities worth pursuing. To explain how entrepreneurial ecosystem attributes influence EA and how EA influences ecosystems, we use a microfoundations approach, described next.

The microfoundations approach

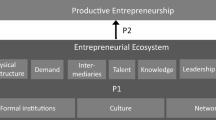

The microfoundations approach to entrepreneurship and organization studies was a reaction to the tendency of scholars to focus on collective constructs and outcomes without examining how macro-level phenomena influenced and were influenced by individual-level actors (Felin & Foss, 2005). Organizational microfoundations research builds on Coleman’s work in sociology, which calls for teasing apart the linkages between the micro-level attributes of individuals and their macro-level social structures (Coleman, 1990). The microfoundations approach asserts that more attention should be paid to multi-level issues and, specifically, to how collectives influence individuals and how individual action “collectivizes” to create social constructs and outcomes (Felin et al., 2015). The microfoundations approach is especially appropriate for understanding multi-level socio-economic ecosystems (Felin & Foss, 2023). In the spirit of the microfoundations approach, we contend that EA research could also benefit from devoting more attention to multi-level issues and, particularly, to how EA, as a micro-level attribute of entrepreneurs, interacts with entrepreneurs’ macro-level entrepreneurial ecosystems. To begin this exploration, we propose a microfoundations framework, illustrated in Fig. 1.

Connecting EA and entrepreneurial ecosystems

Entrepreneurial ecosystem attributes

A primary thrust in entrepreneurial ecosystems research is identifying and categorizing the attributes of entrepreneurial ecosystems and, particularly, thriving ecosystems that enable high levels of entrepreneurial activity (e.g., Spigel, 2017; Stam & Van de Ven, 2021). Although there is some debate about the extent to which ecosystem attributes are common across types of entrepreneurial ecosystems (e.g., urban versus rural; high- versus low-income), Spigel (2017) proposed an intuitive and flexible framework for organizing entrepreneurial ecosystem elements consisting of three categories: social, cultural, and material ecosystem attributes. Subsequent research has supported and refined this framework (e.g., Loots et al., 2021). The social-cultural-material entrepreneurial ecosystems framework is akin to other models of social systems that explain how individuals interact with society and their environments (e.g., material, social, and cultural ecosystem attributes roughly map onto Harris’s (2001) infrastructure-structure-superstructure framework). Spigel’s model is useful for organizing how entrepreneurs’ local ecosystems shape their EA, which in turn influences their entrepreneurial actions (Fig. 1, pathways 1 and 2).

EA and social ecosystem attributes

The social attributes of an entrepreneurial ecosystem are based on the ties among ecosystem participants and create relational resources for entrepreneurs (Scott et al., 2022). Entrepreneurs gain access to relational resources by becoming embedded in entrepreneurial ecosystem networks, which consist of the formal and informal relationships in a startup community (Sperber & Linder, 2019). Ecosystem networks connect entrepreneurs to actors in their local environments and their assets, capital, and resources. However, networks are not uniform across entrepreneurial ecosystems; ecosystems differ in their network size and composition (Fernandes & Ferreira, 2022). For instance, the networks of entrepreneurial ecosystems in small towns are often smaller but composed of stronger connections than the networks of large cities (Roundy, 2017). Important differences also exist across resource-endowed ecosystems in their networks (cf. Breznitz & Taylor, 2014). For example, Pittz et al. (2021) compared differences in the networks of “dealmakers” (i.e., influential EE participants who connect other EE participants and actively steward regional development; cf. Feldman & Zoller, 2012) in the Tampa, USA and Seattle, USA entrepreneurial ecosystems and found that the density of the Seattle dealmaker network was much higher. Pittz et al. (2021: 1281) explained how this finding “follows previous research that has shown how the most anemic entrepreneurial ecosystems have very few dealmakers, whereas [dealmakers] in Silicon Valley and Boston are nearly innumerable.” Thus, critical differences exist across entrepreneurial ecosystems in the structure and density of their network connections.

Network connections are fundamental to entrepreneurial ecosystem functioning because they enable knowledge and capital to flow among ecosystem participants, which is impactful because EA depends on entrepreneurs being able to access clusters of external information (Minniti, 2004). In this function, entrepreneurial ecosystem networks serve as a distributed, community-level transactive memory system (cf. Lazar et al., 2022) that helps entrepreneurs and other ecosystem participants to navigate “who knows what?” in the ecosystem (Roundy, 2020a). For instance, ecosystem networks can connect entrepreneurs to local mentors, other entrepreneurs, investors, and members of support organizations, who can be sources of human and financial capital (Fernandes & Ferreira, 2022). Ecosystem networks also contain strong and weak ties that provide entrepreneurs with access to new and diverse information (Neumeyer et al., 2019). In addition to disseminating ideas and innovations, ecosystem networks can be used to gain feedback on ideas. Thus, entrepreneurial ecosystems’ social attributes influence EA through network ties that shape what entrepreneurs observe in their local environments, not only by connecting entrepreneurs to information and other resources that they can then begin to associate with new venture ideas but also by linking entrepreneurs to sources of feedback that allow them to evaluate the validity of their budding ideas.

EA and cultural ecosystem attributes

An entrepreneurial ecosystem’s cultural attributes stem from its culture—an ecosystem’s “collective commonality of perspectives” about entrepreneurship (Donaldson, 2021: 289). Ecosystem culture is a constellation of a startup community’s values, norms, beliefs, logics, narratives, and simple rules, which guide ecosystem behaviors and represent how entrepreneurs and other ecosystem participants believe they should act in ecosystem interactions (Muldoon et al., 2018; Walsh & Winsor, 2019). Cultural attributes are produced, reinforced, and transmitted during the interactions among ecosystem participants and shaped by a community’s formal and informal institutions (Stam & Van de Ven, 2021).

In thriving, or “effective”, entrepreneurial ecosystems (i.e., ecosystems that enable high levels of entrepreneurial activity), the culture supports at least two shared “logics of action” (Audretsch et al., 2021a; Spicer & Zhong, 2022): an entrepreneurial logic focused on value creation, opportunity pursuit, and innovation, and a community logic focused on cooperation, trust, prosocial (i.e., helping) behaviors, and community development (Roundy, 2017; Muldoon et al., 2018; Thornton et al., 2012). The entrepreneurial logic encourages ecosystem participants to act like entrepreneurs (e.g., creating and pursuing new sources of value and disrupting the status quo). Ecosystem culture also encourages individuals to take risks, tolerate failure, and engage in customer discovery, all of which are tied to an entrepreneurial logic. The community logic encourages ecosystem participants to help one another in their pursuit of opportunities and to invest in developing the entrepreneurial ecosystem. For instance, Feld (2012) sought to understand what makes the Boulder, Colorado entrepreneurial ecosystem a fertile environment for entrepreneurs and noted that ecosystem participants operate based on simple rules, such as “give [to the ecosystem] before taking” resources. Other studies have noted the importance of values that favor a collaborative spirit, camaraderie, cooperation, social responsibility to the community, and helping others (Roundy, 2019). Tensions can exist between the values associated with entrepreneurial and community logics, and these tensions may be more intense in some countries. For instance, in collectivist cultures, the community logic may be viewed as more legitimate than other logics (cf. Vu et al., 2023). However, both community and entrepreneurial logics are necessary for a functioning entrepreneurial ecosystem (cf. Korber et al., 2022; Roundy, 2017).

Entrepreneurial ecosystem culture influences EA through several potential mechanisms. As described, in thriving ecosystems the culture promotes an entrepreneurial logic, which encourages entrepreneurs to be aware of opportunities by engaging in environmental observation. In contrast, in entrepreneurial ecosystems that do not encourage an entrepreneurial logic, the pursuit of opportunities and the disruption of the status quo are not encouraged, which means that entrepreneurs will not have the same incentives to observe their environments for cues that suggest new venture ideas. In thriving entrepreneurial ecosystem cultures, the community logic encourages entrepreneurs to work together, share information, and make introductions, which gives entrepreneurs more opportunities to observe environmental information and operates as a conduit for the flow of information and other resources that entrepreneurs can combine into new ideas. Another aspect of thriving entrepreneurial ecosystems is that their culture contains stories of entrepreneurship, which are passed among ecosystem participants (Harima et al., 2021). Ecosystem stories contain the narratives of successful entrepreneurs in the ecosystem (e.g., stories of entrepreneurs who have experienced large IPOs or lucrative financial exits), historical accounts of entrepreneurial activities in the region (e.g., stories of the earliest notable entrepreneurs in the ecosystem), and future-oriented narratives describing an imagined trajectory of the ecosystem (e.g., stories describing how the ecosystem could one day become a global hub for a specific type of innovation) (Hubner et al., 2021; Roundy, 2016). As studies of narratives across organizational contexts have demonstrated, stories can help audiences create connections between disparate objects (Vaara et al., 2016); over time this can lead to schema development as entrepreneurs are exposed to more stories (which is the general principle supporting the case method pedagogy in business schools). In functioning this way, stories represent vicarious learning opportunities (Myers, 2022) that help entrepreneurs create associations between ideas and resources. Finally, thriving entrepreneurial ecosystems have cultures that encourage entrepreneurs to refine ideas through an iterative and recursive process of trial and error (Donaldson, 2021; Feld & Hathaway, 2020; Grande et al., 2023). Entrepreneurial ecosystems provide learning opportunities that encourage entrepreneurs to learn by testing and evaluating their ideas.

EA and material ecosystem attributes

The material attributes of an entrepreneurial ecosystem have a physical presence in a geographic place and are tied to the tangible elements in a local environment (Spigel, 2017). Material attributes include an ecosystem’s meeting and event spaces, support organizations, university campuses, natural environment, and co-working spaces (Lô & Theodoraki, 2020; Spigel, 2017). The material spaces of an entrepreneurial ecosystem serve as the physical setting in which social and cultural ecosystem attributes manifest and are reinforced. Social interactions, the transmission of culture, and important changes in sensemaking often take place in an ecosystem’s material spaces (Hoyte et al., 2019). For instance, the economic and community logics (cultural attribute) emphasized in the trainings and events held at support organizations (material attribute) can shape the norms of ecosystem participants (cultural attribute) and, in turn, how ecosystem participants interact and maintain connections with one another (social attribute) (Roundy, 2017). As another example of the interplay between ecosystem attributes, low levels of trust in an entrepreneurial ecosystem, which is a cultural attribute, may be exacerbated by the ecosystem having scarce material resources, which causes ecosystem participants to have a competitive, self-interest-driven mindset, rather than a cooperative, “ecosystem” mindset (cf. Muldoon et al., 2018; Roundy, 2023). Because of the connections between the different types of ecosystem attributes, Muñoz et al. (2022: 11) claim that “to explain differences between low-growth and high-growth entrepreneurial activity” across ecosystems, it is necessary to consider the “combinatorial possibilities of doubly constructed social, cultural and material attributes” (i.e., attributes constructed by actors’ evaluations and narratives) rather than looking at attributes in isolation. Thus, the social, cultural, and material attributes of ecosystems are interdependent (Loots et al., 2021) and, as Spigel (2017) contends, should be conceptualized as three interconnected layers of the same community.

In the physical environments that constitute the material attributes of an ecosystem, entrepreneurs have unplanned “collisions” (Nylund & Cohen, 2017) with ecosystem participants (e.g., local customers, other entrepreneurs in the community, mentors) that expose alert entrepreneurs to information and reveal value-creating opportunities. For instance, entrepreneurs who attend campus networking events can gain insights from other participants that stimulate entirely new business ideas and opportunities; in addition, these types of material settings can provide alert entrepreneurs with the opportunity to learn from the successes, failures, and feedback of other ecosystem participants, which may cause them to pivot or iterate on their initial ideas (cf. Pugh et al., 2021). Entrepreneurs also take part in events in the material spaces of ecosystems that are explicitly aimed at generating and refining new ideas, such as “hackathons” (Auschra et al., 2018) and pitch competitions (Stolz, 2023). For alert entrepreneurs, these ecosystem interactions and the knowledge entrepreneurs’ gain from these interactions not only are early sources of inspiration for opportunities but also expose entrepreneurs to novel and slack resources, which they can capitalize on through their EA and bricolage activities (Sun et al., 2020). An ecosystem’s material spaces provide knowledge (stemming from both direct and vicarious learning; cf. Alvarado Valenzuela et al., 2023) that help alert entrepreneurs make associations between resources and evaluate the usefulness of new resources. Ultimately, entrepreneurial ecosystems influence entrepreneurs by being environments with unique social, cultural, and material attributes, each of which influences the dimensions of EA.

EA and entrepreneurial ecosystem outcomes

The microfoundations perspective (Felin et al., 2015) suggests that it is not sufficient to explore only how macro-level characteristics (e.g., ecosystem attributes) influence micro-level attributes (e.g., EA and entrepreneurial actions) (Fig. 1, pathways 1 and 2). It is also critical to examine how the micro-dynamics of EA and entrepreneurial actions aggregate to influence entrepreneurial ecosystem attributes and outcomes (Fig. 1, pathways 3 and 4). We explain how EA influences the social, cultural, and material attributes of entrepreneurial ecosystems which, in turn, influence two specific ecosystem-level attributes (diversity and coherence) and outcomes (resilience and coordination) (Fig. 1, pathways 3 and 4).

EA and ecosystem attributes

EA can aggregate to influence ecosystem attributes in several ways. As described, even though EA is an internal attribute of entrepreneurs, each of its dimensions has a strong external focus. Specifically, through observation, resource association, and idea evaluation, alert entrepreneurs are hyper-aware of what is happening in their external environments (Lanivich et al., 2022). Since alert entrepreneurs are attentive to their environments, which include their local entrepreneurial ecosystems, they will be more likely than non-alert entrepreneurs to see opportunities for their ecosystems to assist in the entrepreneurship process. As a result, alert entrepreneurs will be more likely to utilize their ecosystems by seeking and providing resources. For instance, alert entrepreneurs position themselves in the flow of information (Kaish & Gilad, 1991) by pursuing interactions with ecosystem participants. Alert entrepreneurs are more likely to be attuned to the benefits of ecosystem relationships and how such relationships can enable recognizing and predicting entrepreneurial opportunities (Adomako et al., 2018). In this way, entrepreneurs are alert for network connections that can provide access to information and other resources needed for opportunity pursuit. Pursuing opportunities also gives alert entrepreneurs greater demand for material resources tied to support organizations and to other aspects of an ecosystem’s physical infrastructure, such as its meeting spaces.

When aggregated, network-seeking and network-utilizing activity creates ties in entrepreneurial ecosystems and, when this activity collectivizes, it means that ecosystems with alert entrepreneurs will have dense networks (Spigel & Harrison, 2018). At the system level, resource-seeking and provisioning behaviors will influence entrepreneurial ecosystem attributes by creating a demand-side (Hechavarria & Ingram, 2019) “pull” on ecosystem development.

EA also affects entrepreneurial ecosystem functioning by influencing ecosystem culture. Alert entrepreneurs, almost by definition of their EA (cf. Tang et al., 2012), exhibit an entrepreneurial logic, which is one of the lynchpins of a thriving entrepreneurial ecosystem culture (Roundy, 2017). As more alert entrepreneurs recognize and pursue opportunities, and the amount of entrepreneurial activity increases, entrepreneurial ecosystems become more effective and can support higher levels of entrepreneurial activity. Likewise, EA may indirectly strengthen an ecosystem’s community logic (Thornton et al., 2012) if alert entrepreneurs are more likely to see opportunities to work together with other ecosystem members for their benefit and the benefit of the community.

EA and ecosystem diversity, coherence, and resilience

If an entrepreneurial ecosystem has many alert entrepreneurs, this increases the number of opportunities recognized and created, and may even increase the level of firm innovation in the ecosystem (cf. Tang et al., 2021), which may influence the structural attributes of an ecosystem, including ecosystem diversity and coherence. Ecosystem diversity is the degree to which an entrepreneurial ecosystem contains a broad representation of participants, venture types, and business models (Kuckertz, 2019; Roundy et al., 2018a). In contrast, ecosystem coherence is the degree of commonality among the activities of ecosystem participants (e.g., many entrepreneurs engaged in customer discovery) (Roundy et al., 2018a; Sepulveda-Calderon et al., 2022).

As the number of alert entrepreneurs in an ecosystem increases, more opportunities are pursued, which increases ecosystem diversity; at the same time, more individuals are engaged in entrepreneurship, which increases ecosystem coherence. Diversity and coherence are important because, together, they help to determine an ecosystem’s resilience, which is the extent to which an entrepreneurial ecosystem can continuously recover from and adapt to exogenous disruptions and endogenous pressures to change (Cho et al., 2022; Roundy et al., 2017; Ryan et al., 2021). Thus, an entrepreneurial ecosystem with a thriving stock of alert entrepreneurs will collectively influence the system’s ability to respond to internal and environmental disruptions.

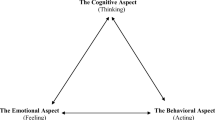

EA and ecosystem coordination

Another way to conceptualize the aggregate effects of EA on entrepreneurial ecosystem attributes, and to parse the specific mechanisms driving the potential relationship between EA and ecosystem outcomes (Fig. 1, pathways 1, 3, and 4), is by considering how alert entrepreneurs influence ecosystem coordination: the degree to which an ecosystem’s elements are organized and orchestrated to support ecosystem development (Knox & Arshed, 2022; Scott et al., 2022). Coordination represents the interdependence and cohesiveness of ecosystem functioning and has been conceptualized as consisting of three dimensions: cognitive, social, and cultural (Roundy, 2020a).

When an ecosystem has cognitive coordination, its participants explicitly draw attention to and seek to develop the ecosystem, which reifies its existence and makes the ecosystem a distinct entity in participants’ minds (Goswami et al., 2018). That is, if cognitive coordination exists in an ecosystem, community members think about the community’s local startup community as an “entrepreneurial ecosystem” and take actions to engage with and bolster it. Alert entrepreneurs’ heightened and frequent interactions with their entrepreneurial ecosystems will help to reify the ecosystem and increase the ecosystem’s entitativity—i.e., how much the ecosystem is viewed as a distinct entity in the eyes of community members.

In entrepreneurial ecosystems with social coordination, strong relationships and dense network ties connect EE participants (e.g., Theodoraki et al., 2018). These networks contain knowledge brokers and “entrepreneurial dealmakers” who coordinate the players in the ecosystem and the flow of resources among ecosystem participants (Colombo et al., 2019; Goswami et al., 2018: 117). EA will increase social coordination because alert entrepreneurs will be primed to observe and be aware of ways in which social connections in the ecosystem can benefit them.

Lastly, in entrepreneurial ecosystems with cultural coordination, ecosystem participants share norms, logics, values, and narratives, which create a common culture and shared vision for the ecosystem (Donaldson, 2021; Spigel, 2016). Cultural coordination is increased by alert entrepreneurs when they exhibit and reinforce the entrepreneurial logic. Thus, EA influences not only the presence and strength of entrepreneurial ecosystem attributes (Fig. 1, pathway 3) but also ecosystem functioning and outcomes by influencing how attributes are coordinated (Fig. 1, pathway 4).

Finally, it should be noted that, as with other cross-level effects in entrepreneurial ecosystems (Roundy et al., 2018a), there are likely to be positive feedback loops between EA and ecosystem outcomes. For instance, as entrepreneurial ecosystems become more coordinated, they represent increasingly fertile environments for entrepreneurs to observe and respond to, which, in turn, can fuel alertness. Heightened alertness increases entrepreneurs’ likelihood of leveraging and contributing ecosystem resources, which makes an ecosystem more coordinated. That is, circular, self-reinforcing effects exist between EA and ecosystem outcomes: ecosystem outcomes strengthen EA which, when aggregated through the actions of a community’s entrepreneurs, improves ecosystem outcomes.

Discussion

In the section that follows, we outline a multi-level agenda for future research that combines cognition and context by exploring the interface of EA and entrepreneurial ecosystems. To structure our discussion and the opportunities we propose for future research, we once again utilize the microfoundations framework described in the previous section. We then expand the framework and propose further research questions by adding another level of analysis relevant to EA: ecosystem leadership.

An agenda for research on EA and entrepreneurial ecosystems

At the micro-, entrepreneur-level of analysis (i.e., Fig. 1, pathway 1), research is needed that explores the mechanisms underlying how EA influences entrepreneurs’ pursuit of opportunities within their entrepreneurial ecosystems. For instance, as we have posited, EA is likely to influence how entrepreneurs interact with their local ecosystems and, specifically, their ecosystem-related behaviors, such as the propensity to find opportunities to seek and contribute resources. Research on this aspect of the interface between EA and entrepreneurial ecosystems could shed light on several critical issues. For example, EA may prove to be a key factor explaining why some entrepreneurs implicitly adopt a “go-it-alone” strategy (Baum et al., 2000) and are not attuned to the information and resources in their local entrepreneurial ecosystems, while others are quick to identify how their ecosystems can assist them in opportunity recognition.

In this function, EA may represent a central aspect of entrepreneurs having an “ecosystem mindset”—an orientation that involves looking for and embracing opportunities to leverage local contexts during venture development (Ratten, 2020). The factors that determine why some entrepreneurs have an ecosystem mindset, while others do not get “plugged in” (Stephens et al., 2019) to their ecosystems, “represents a far-reaching, but untheorized, source of variation” among entrepreneurs (Roundy & Lyons, 2022: 1). In general, research is only beginning to examine how the social-psychological and moral attributes of entrepreneurs influence the degree to which they engage in entrepreneurial ecosystem resource seeking and contributing behaviors. Future research that focuses on understanding how individual-level, micro-dynamics influence ecosystem-related behaviors may find that EA works alongside other socio-cognitive entrepreneurial attributes, such as humility (cf. Chandler et al., 2023), in influencing the degree to which entrepreneurs have an ecosystem mindset and look to their ecosystems for assistance.

Beyond the effects of EA on the ecosystem-oriented behaviors of entrepreneurs, research is needed to explore how entrepreneurs’ EA-induced actions and activities influence other ecosystem attributes (Fig. 1, pathway 3) and outcomes (pathway 4). We have focused on how, when alert entrepreneurs’ behaviors are aggregated, EA is likely to influence several attributes of entrepreneurial ecosystems, such as their social, cultural, and material attributes (Spigel, 2017) and, in turn, ecosystem diversity, coherence, resilience, and coordination (Knox & Arshed, 2022; Roundy et al., 2017; Ryan et al., 2021). We contend that EA affects ecosystem outcomes directly (pathway 4), through its influence on ecosystem attributes (pathway 3) and, in turn, through the effects of these attributes on ecosystem outcomes (pathway 5). However, research is needed that analyzes the mechanisms driving these effects and explores the influence of EA on other entrepreneurial ecosystem attributes and outcomes, such as ecosystem performance and innovation (Shen et al., 2023).

Opportunities also exist for research to study the positive feedback loop that we theorize between EA and entrepreneurial ecosystems—i.e., as the EA of a region’s entrepreneurs increases, entrepreneurial ecosystem functioning improves (in part through increased ecosystem coordination), which in turn improves the alertness of entrepreneurs. This positive feedback loop creates a potential “chicken or egg” problem that is common in complex systems with recursive effects (cf. Tsoukas & Cunha, 2017). To understand this problem, it is necessary for future research to adopt a temporal approach and to tease apart the timing of EA-entrepreneurial ecosystem dynamics (Audretsch et al., 2021). We also agree that it is important to identify the conditions in which EA-entrepreneurial ecosystem linkages are strongest and weakest. For instance, perhaps the positive feedback loop between EA and ecosystem dynamics is strongest in small, under-resourced ecosystems and weakest in large and highly munificent ecosystems because, in small ecosystems, there are fewer alert entrepreneurs engaging in entrepreneurial activities and, thus, the effects of any one entrepreneur’s actions on ecosystem dynamics is more significant (cf. Tang et al., 2021).

In addition to identifying the mechanisms underlying the micro- and macro-linkages between the entrepreneur and ecosystem levels of analysis, future research could build on our initial framework by exploring how EA influences a different type of ecosystem participant: ecosystem leaders. Entrepreneurial ecosystem leaders are individuals who engage in deliberate activities aimed at building and developing an ecosystem and improving its functioning (Harper-Anderson, 2018; Miles & Morrison, 2020). Ecosystem leaders work “on” (rather than exclusively “in”) their entrepreneurial ecosystems. Ecosystem leadership is a form of distributed community leadership (cf. Eva et al., 2021) that any participant in an ecosystem—including entrepreneurs—can step into (Roundy, 2020b).

Exploring how EA influences entrepreneurial ecosystem leadership suggests an expanded microfoundations framework with an additional level of analysis. The expanded framework would explain how ecosystem leader attributes, including leader EA, influence their leadership behaviors, involving pursuing opportunities to develop and orchestrate their ecosystems, which, in turn, influence ecosystem attributes and outcomes. For instance, research could examine if ecosystem leaders differ in their alertness to opportunities to improve their entrepreneurial ecosystems (e.g., opportunities to attract new resources to the system or increase the effectiveness of its networks), which may influence the trajectory and vitality of the ecosystems.

Finally, we have focused primarily on intra-ecosystem dynamics and how EA influences entrepreneurs’ interactions with their local communities. However, research is also needed that considers forces “outside” entrepreneurs’ local startup communities and explores the interacting effects of entrepreneurs’ local and non-local environments on EA. For example, future research could examine how attributes of entrepreneurs’ general business ecosystems (cf. Adner, 2017), such as the digital platforms that entrepreneurs increasingly utilize (Sussan & Acs, 2017) and are often globally distributed, interact with their EA and entrepreneurial ecosystems.

Conclusion

In the past decade, research has made considerable progress in understanding the role of EA in the psychology of entrepreneurs. However, we contend that important insights about EA and the entrepreneurship process may be uncovered by combining the primary focus of EA research—cognition—with an emphasis on context. Specifically, in this perspectives essay we have sought to enhance the “understanding of the role of EA in the nomological network of entrepreneurship research” (Tang et al., 2022) by explaining how EA informs—and is informed by—contextual work on entrepreneurial ecosystems. Going forward, we call for scholars to expand the lens of EA research to include local contexts, explore the multi-level dynamics involved in EA, and design studies to understand how entrepreneurs’ alertness influences and is influenced by local entrepreneurial ecosystems.

References

Acs, Z. J., Stam, E., Audretsch, D. B., & O’Connor, A. (2017). The lineages of the entrepreneurial ecosystem approach. Small Business Economics, 49(1), 1–10.

Adner, R. (2017). Ecosystem as structure: An actionable construct for strategy. Journal of Management, 43(1), 39–58.

Adomako, S., Danso, A., Boso, N., & Narteh, B. (2018). Entrepreneurial alertness and new venture performance: Facilitating roles of networking capability. International Small Business Journal, 36(5), 453–472.

Alvarado Valenzuela, J. F., Wakkee, I., Martens, J., & Grijsbach, P. (2023). Lessons from entrepreneurial failure through vicarious learning. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 35(5), 762–786.

Audretsch, D. B., Belitski, M., & Cherkas, N. (2021a). Entrepreneurial ecosystems in cities: The role of institutions. PloS One, 16(3), e0247609.

Audretsch, D., Mason, C., Miles, M. P., & O’Connor, A. (2021b). Time and the dynamics of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 33(1–2), 1–14.

Auschra, C., Braun, T., Schmidt, T., & Sydow, J. (2018). Patterns of project-based organizing in new venture creation: Projectification of an entrepreneurial ecosystem. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, 12(1), 48–70.

Baum, J. A., Calabrese, T., & Silverman, B. S. (2000). Don’t go it alone: Alliance network composition and startups’ performance in Canadian biotechnology. Strategic Management Journal, 21(3), 267–294.

Breznitz, D., & Taylor, M. (2014). The communal roots of entrepreneurial–technological growth–social fragmentation and stagnation: Reflection on Atlanta’s technology cluster. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 26(3–4), 375–396.

Bruton, G. D., Ahlstrom, D., & Si, S. (2015). Entrepreneurship, poverty, and Asia: Moving beyond subsistence entrepreneurship. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 32, 1–22.

Chandler, J. A., Johnson, N. E., Jordan, S. L., & Short, J. C. (2023). A meta-analysis of humble leadership: Reviewing individual, team, and organizational outcomes of leader humility. The Leadership Quarterly, 34(1), 101660.

Chavoushi, Z. H., Zali, M. R., Valliere, D., Faghih, N., Hejazi, R., & Dehkordi, A. M. (2021). Entrepreneurial alertness: A systematic literature review. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 33(2), 123–152.

Cho, D. S., Ryan, P., & Buciuni, G. (2022). Evolutionary entrepreneurial ecosystems: A research pathway. Small Business Economics, 58(4), 1865–1883.

Coleman, J. S. (1990). Foundations of Social Theory. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press

Colombo, M. G., Dagnino, G. B., Lehmann, E. E., & Salmador, M. (2019). The governance of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Small Business Economics, 52(2), 419–428.

Donaldson, C. (2021). Culture in the entrepreneurial ecosystem: A conceptual framing. International.

Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 17(1), 289–319.

Eva, N., Cox, J. W., Herman, H. M., & Lowe, K. B. (2021). From competency to conversation: A multi-perspective approach to collective leadership development. The Leadership Quarterly, 32(5), 101346.

Feld, B. (2012). Startup communities: Building an entrepreneurial ecosystem in your city. John Wiley & Sons.

Feld, B., & Hathaway, I. (2020). The startup community way. John Wiley & Sons.

Feldman, M., & Zoller, T. D. (2012). Dealmakers in place: Social capital connections in regional entrepreneurial economies. Regional Studies, 46(1), 23–37.

Felin, T., & Foss, N. J. (2005). Strategic organization: A field in search of micro-foundations. Strategic Organization, 3(4), 441–455.

Felin, T., & Foss, N. (2023). Microfoundations of ecosystems: The theory-led firm and capability growth. Strategic Organization, 14761270231159391.

Felin, T., Foss, N. J., & Ployhart, R. E. (2015). The microfoundations movement in strategy and organization theory. Academy of Management Annals, 9(1), 575–632.

Fernandes, A. J., & Ferreira, J. J. (2022). Entrepreneurial ecosystems and networks: A literature review and research agenda. Review of Managerial Science, 16(1), 189–247.

Goswami, K., Mitchell, J. R., & Bhagavatula, S. (2018). Accelerator expertise: Understanding the intermediary role of accelerators in the development of the Bangalore entrepreneurial ecosystem. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 12(1), 117–150.

Grande, S., Bertello, A., De Bernardi, P., & Ricciardi, F. (2023). Enablers of explorative and exploitative intellectual capital in entrepreneurial ecosystems. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 24(1), 35–69.

Harima, A., Harima, J., & Freiling, J. (2021). The injection of resources by transnational entrepreneurs: Towards a model of the early evolution of an entrepreneurial ecosystem. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 33(1–2), 80–107.

Harper-Anderson, E. (2018). Intersections of partnership and leadership in entrepreneurial ecosystems: Comparing three US regions. Economic Development Quarterly, 32(2), 119–134.

Harris, M. (2001). Cultural Materialism: The struggle for a science of culture. AltaMira Press.

Harrison, R., Scheela, W., Lai, P. C., & Vivekarajah, S. (2018). Beyond institutional voids and the middle-income trap: The emerging business angel market in Malaysia. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 35(4), 965–991.

Hechavarría, D. M., & Ingram, A. E. (2019). Entrepreneurial ecosystem conditions and gendered national-level entrepreneurial activity: A 14-year panel study of GEM. Small Business Economics, 53(2), 431–458.

Hoyte, C., Noke, H., Mosey, S., & Marlow, S. (2019). From venture idea to venture formation: The role of sensemaking, sensegiving and sense receiving. International Small Business Journal, 37(3), 268–288.

Hubner, S., Most, F., Wirtz, J., & Auer, C. (2021). Narratives in entrepreneurial ecosystems: Drivers of effectuation versus causation. Small Business Economics, 1–32.

Kaish, S., & Gilad, B. (1991). Characteristics of opportunities search of entrepreneurs versus executives: Sources, interests, general alertness. Journal of Business Venturing, 6(1), 45–61.

Kapturkiewicz, A. (2022). Varieties of entrepreneurial ecosystems: A comparative study of Tokyo and Bangalore. Research Policy, 51(9), 104377.

Kim, S., Cho, M., & Rhee, M. (2020). A study on Singapore Startup Ecosystem using Regional Transformation of Isenberg (2010). Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Venturing and Entrepreneurship, 15(2), 47–65.

Kirzner, I. M. (1973). Competition and entrepreneurship. University of Chicago Press.

Kirzner, I. M. (1979). Perception, opportunity, and profit. University of Chicago Press.

Knox, S., & Arshed, N. (2022). Network governance and coordination of a regional entrepreneurial ecosystem. Regional Studies, 56(7), 1161–1175.

Korber, S., Swail, J., & Krishanasamy, R. (2022). Endure, escape or engage: How and when misaligned institutional logics and entrepreneurial agency contribute to the maturing of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 34(1–2), 158–178.

Kuckertz, A. (2019). Let’s take the entrepreneurial ecosystem metaphor seriously! Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 11, e00124.

Lanivich, S. E., Smith, A., Levasseur, L., Pidduck, R. J., Busenitz, L., & Tang, J. (2022). Advancing entrepreneurial alertness: Review, synthesis, and future research directions. Journal of Business Research, 139, 1165–1176.

Lazar, M., Miron-Spektor, E., Chen, G., Goldfarb, B., Erez, M., & Agarwal, R. (2022). Forming entrepreneurial teams: Mixing business and friendship to create transactive memory systems for enhanced success. Academy of Management Journal, 65(4), 1110–1138.

Levasseur, L., Tang, J., Karami, M., Busenitz, L., & Kacmar, K. M. (2022). Increasing alertness to new opportunities: The influence of positive affect and implications for innovation. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 39, 27–49.

Lô, A., & Theodoraki, C. (2020). Achieving interorganizational ambidexterity through a nested entrepreneurial ecosystem. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 68(2), 418–429.

Loots, E., Neiva, M., Carvalho, L., & Lavanga, M. (2021). The entrepreneurial ecosystem of cultural and creative industries in Porto: A sub-ecosystem approach. Growth and Change, 52(2), 641–662.

Mani, D. (2021). Who controls the Indian economy: The role of families and communities in the Indian economy. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 38(1), 121–149.

McCaffrey, M. (2014). On the theory of entrepreneurial incentives and alertness. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(4), 891–911.

Miles, M. P., & Morrison, M. (2020). An effectual leadership perspective for developing rural entrepreneurial ecosystems. Small Business Economics, 54(4), 933–949.

Minniti, M. (2004). Entrepreneurial alertness and asymmetric information in a spin-glass model. Journal of Business Venturing, 19(5), 637–658.

Muldoon, J., Bauman, A., & Lucy, C. (2018). Entrepreneurial ecosystem: Do you trust or distrust? Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 12(2), 158–177.

Muñoz, P., Kibler, E., Mandakovic, V., & Amorós, J. E. (2022). Local entrepreneurial ecosystems as configural narratives: A new way of seeing and evaluating antecedents and outcomes. Research Policy, 51(9), 104065.

Myers, C. G. (2022). Storytelling as a tool for vicarious learning among air medical transport crews. Administrative Science Quarterly, 67(2), 378–422.

Neumeyer, X., Santos, S. C., & Morris, M. H. (2019). Who is left out: Exploring social boundaries in entrepreneurial ecosystems. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 44(2), 462–484.

Nylund, P. A., & Cohen, B. (2017). Collision density: Driving growth in urban entrepreneurial ecosystems. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 13(3), 757–776.

Pidduck, R. J., Busenitz, L. W., Zhang, Y., & Moulick, A. G. (2020). Oh, the places you’ll go: A schema theory perspective on cross-cultural experience and entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 14, e00189.

Pittz, T. G., White, R., & Zoller, T. (2021). Entrepreneurial ecosystems and social network centrality: The power of regional dealmakers. Small Business Economics, 56, 1273–1286.

Pugh, R., Soetanto, D., Jack, S. L., & Hamilton, E. (2021). Developing local entrepreneurial ecosystems through integrated learning initiatives: The Lancaster case. Small Business Economics, 56, 833–847.

Ratten, V. (2020). Entrepreneurial ecosystems: Future research trends. Thunderbird International Business Review, 62(5), 623–628.

Roundy, P. T. (2016). Start-up community narratives: The discursive construction of entrepreneurial ecosystems. The Journal of Entrepreneurship, 25(2), 232–248.

Roundy, P. T. (2017). Hybrid organizations and the logics of entrepreneurial ecosystems. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 13(4), 1221–1237.

Roundy, P. T. (2019). Back from the brink: The revitalization of inactive entrepreneurial ecosystems. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 12, e00140.

Roundy, P. T. (2020a). The wisdom of ecosystems: A transactive memory theory of knowledge management in entrepreneurial ecosystems. Knowledge and Process Management, 27(3), 234–247.

Roundy, P. T. (2020b). Do we lead together? Leadership behavioral integration and coordination in entrepreneurial ecosystems. Journal of Leadership Studies, 14(1), 6–25.

Roundy, P. T. (2023). Embracing the village or going-it-alone? Understanding the entrepreneurial ecosystem mindset. In J. A. Cunningham, M. Menter, C. O’Kane, & M. Romano (Eds.), Research Handbook on Entrepreneurial ecosystems. Edward Elgar.

Roundy, P. T., & Lyons, T. S. (2022). Humility in social entrepreneurs and its implications for social impact entrepreneurial ecosystems. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 17, e00296.

Roundy, P. T., & Lyons, T. S. (2023). Where are the entrepreneurs? A call to theorize the micro-foundations and strategic organization of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Strategic Organization, 21(2), 447–459.

Roundy, P. T., Brockman, B. K., & Bradshaw, M. (2017). The resilience of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 8, 99–104.

Roundy, P. T., Bradshaw, M., & Brockman, B. K. (2018a). The emergence of entrepreneurial ecosystems: A complex adaptive systems approach. Journal of Business Research, 86, 1–10.

Roundy, P. T., Harrison, D. A., Khavul, S., Pérez-Nordtvedt, L., & McGee, J. E. (2018b). Entrepreneurial alertness as a pathway to strategic decisions and organizational performance. Strategic Organization, 16(2), 192–226.

Ryan, P., Giblin, M., Buciuni, G., & Kogler, D. F. (2021). The role of MNEs in the genesis and growth of a resilient entrepreneurial ecosystem. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 33(1–2), 36–53.

Scott, S., Hughes, M., & Ribeiro-Soriano, D. (2022). Towards a network-based view of effective entrepreneurial ecosystems. Review of Managerial Science, 16(1), 157–187.

Sepulveda-Calderon, M., Castro-Ríos, G. A., & Montes-Guerra, M. I. (2022). The role of diversity and coherence in the emergence and consolidation of a regional entrepreneurial ecosystem. Management Research, 20(1), 59–87.

Sharma, L. (2019). A systematic review of the concept of entrepreneurial alertness. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 11(2), 217–233.

Shen, R., Guo, H., & Ma, H. (2023). How do entrepreneurs’ cross-cultural experiences contribute to entrepreneurial ecosystem performance? Journal of World Business, 58(2), 101398.

Sperber, S., & Linder, C. (2019). Gender-specifics in start-up strategies and the role of the entrepreneurial ecosystem. Small Business Economics, 53(2), 533–546.

Spicer, J., & Zhong, M. (2022). Multiple entrepreneurial ecosystems? Worker cooperative development in Toronto and Montréal. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 54(4), 611–633.

Spigel, B. (2016). Developing and governing entrepreneurial ecosystems: The structure of entrepreneurial support programs in Edinburgh, Scotland. International Journal of Innovation and Regional Development, 7(2), 141–160.

Spigel, B. (2017). The relational organization of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41(1), 49–72.

Spigel, B., & Harrison, R. (2018). Toward a process theory of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 12(1), 151–168.

Spigel, B., & Vinodrai, T. (2021). Meeting its Waterloo? Recycling in entrepreneurial ecosystems after anchor firm collapse. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 33(7–8), 599–620.

Stam, E. (2015). Entrepreneurial ecosystems and regional policy: A sympathetic critique. European Planning Studies, 23(9), 1759–1769.

Stam, E., & Van de Ven, A. (2021). Entrepreneurial ecosystem elements. Small Business Economics, 56(2), 809–832.

Stam, E., & Welter, F. (2021). Geographical contexts of entrepreneurship: Spaces, places and entrepreneurial agency. In M. Gielnik, M. Frese, & M. Cardon (Eds.), The psychology of entrepreneurship: The next decade (pp. 263–281).

Stephens, B., Butler, J. S., Garg, R., & Gibson, D. V. (2019). Austin, Boston, Silicon Valley, and New York: Case studies in the location choices of entrepreneurs in maintaining the Technopolis. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 146, 267–280.

Stolz, L. (2023). Start-up competitions as anchor events in Entrepreneurial ecosystems: First findings from two German regions. Geografiska Annaler: Series B Human Geography, 105(1), 38–57.

Sun, S. L., Shi, W. S., Ahlstrom, D., & Tian, L. R. (2020a). Understanding institutions and entrepreneurship: The microfoundations lens and emerging economies. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 37(4), 957–979.

Sun, Y., Du, S., & Ding, Y. (2020b). The relationship between slack resources, resource bricolage, and entrepreneurial opportunity identification—based on resource opportunity perspective. Sustainability, 12(3), 1199.

Sussan, F., & Acs, Z. J. (2017). The digital entrepreneurial ecosystem. Small Business Economics, 49(1), 55–73.

Tang, J. (2008). Environmental munificence for entrepreneurs: Entrepreneurial alertness and commitment. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 14(3), 128–151.

Tang, J., Kacmar, K. M. M., & Busenitz, L. (2012). Entrepreneurial alertness in the pursuit of new opportunities. Journal of Business Venturing, 27(1), 77–94.

Tang, J., Baron, R. A., & Yu, A. (2021a). Entrepreneurial alertness: Exploring its psychological antecedents and effects on firm outcomes. Journal of Small Business Management, 1–30.

Tang, J., Levasseur, L., Karami, M., & Busenitz, L. (2021b). Being alert to new opportunities: It is a matter of time. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 15, e00232.

Tang, J., Zhang, S. X., & Lin, S. (2021c). To reopen or not to reopen? How entrepreneurial alertness influences small business reopening after the COVID-19 lockdown. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 16, e00275.

Tang, J., Ahlstrom, D., Corbett, A., Pattnaik, C., & Pollack, J. (2022). Entrepreneurial alertness: Theoretical, empirical, and Asia Pacific perspectives. Asia Pacific Journal of Management.

Theodoraki, C., Messeghem, K., & Rice, M. P. (2018). A social capital approach to the development of sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystems: An explorative study. Small Business Economics, 51(1), 153–170.

Thornton, P. H., Ocasio, W., & Lounsbury, M. (2012). The Institutional Logics Perspective: A New Approach to Culture, structure, and process. Oxford University Press.

Tsoukas, H., & Cunha, M. P. (2017). On organizational circularity: Vicious and virtuous cycles in organizing. In W. K. Smith, M. W. Lewis, P. Jarzabkowski, & A. Langley (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Organizational Paradox (pp. 393–412). Oxford University Press.

Vaara, E., Sonenshein, S., & Boje, D. (2016). Narratives as sources of stability and change in organizations: Approaches and directions for future research. Academy of Management Annals, 10(1), 495–560.

Valliere, D. (2013). Towards a schematic theory of entrepreneurial alertness. Journal of Business Venturing, 28(3), 430–442.

Vu, M. C., Cruz, D., A., & Burton, N. (2023). Contributing to the sustainable development goals as normative and instrumental acts: The role of Buddhist religious logics in family SMEs. International Small Business Journal, (ahead-of-print).

Walsh, J., & Winsor, B. (2019). Socio-cultural barriers to developing a regional entrepreneurial ecosystem. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 13(3), 263–282.

Wang, J., Chen, S., & Scheela, W. (2022). Foreign venture capital investing strategies in transition economies: The case of China. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 1–44.

Welter, F., & Baker, T. (2021). Moving contexts onto new roads: Clues from other disciplines. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 45(5), 1154–1175.

Welter, F., Baker, T., & Wirsching, K. (2019). Three waves and counting: The rising tide of contextualization in entrepreneurship research. Small Business Economics, 52(2), 319–330.

Wurth, B., Stam, E., & Spigel, B. (2022). Toward an entrepreneurial ecosystem research program. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 46(3), 729–778.

Yang, K. M., Tang, J., Donbesuur, F., & Adomako, S. (2023). Institutional support for entrepreneurship and new venture internationalization: Evidence from small firms in Ghana. Journal of Business Research, 154, 113360.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Roundy, P.T., Im, S. Combining cognition and context: entrepreneurial alertness and the microfoundations of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Asia Pac J Manag (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-024-09951-7

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-024-09951-7