Abstract

Private infrastructure investment is profitable only if followed by a sufficiently high price, but pricing may be subject to regulation. We study markets where regulation is determined by elected policymakers. If price regulation is subject to manipulation then private investors may delay investment fearing an electoral pressure on future prices, leading to a holdup inefficiency. This could possibly be alleviated by regulatory independence, where policymakers can no longer influence the prices. However, to encourage investment the policymakers may install regulation that serves the interests of the infrastructure owners (“regulatory capture”) and lead to inefficient pricing. Regulatory independence can then be detrimental as it may entrench this capture. Whether inefficiencies can be moderated by creating regulatory independence therefore depends on the policymakers’ objectives. We provide experimental evidence for such capture entrenchment and detrimental effects of regulatory independence that therefore arise. Even without independence, the uninformed voters do not provide sufficient pressure to remove these effects. On the other hand, we observe that regulatory independence does reduce holdup inefficiency when policymakers align with the public interest.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

In the worldwide wave of privatization of state-owned natural monopolies that have characterized the past three decades, unbundling of infrastructure and operations has been a consistent policy (Kessides, 2004; Klein & Gray, 1997). This implies a vertical separation of ownership of elements where competition is possible from those where natural monopoly is believed to exist. Whereas the competitive environment of the operations generally suffices to achieve high levels of efficiency, the ownership elements characterized by natural monopoly provide policymakers with obvious efficiency challenges.

Relevant examples include privatization policies where the provision of infrastructure is separated from the generation of the utility. This allows for competition in generation that is not hindered by the natural monopoly characteristics of the infrastructure.Footnote 1 Consider, for example, a competitive market for the generation of electric power that has been vertically separated from the distribution infrastructure (cables, etc.), which is supplied by a (regulated) network operator. Both the demand and the supply side of the competitive market have been subject to rapid development. On the one hand, the demand for electricity is expected to rise rapidly in the foreseeable future (Campillo et al., 2012; Knobloch et al., 2020; van Vliet et al., 2011). On the other hand, new technology has enabled decentralized generation of electricity via, e.g., micro-CHP,Footnote 2 solar panels, or rooftop windmills. As a consequence, the demand for the service provided by the infrastructure may challenge capacity constraints that can be relaxed only if the network operator invests in its expansion. Infrastructure investments are of course risky because the future developments of demand and supply are uncertain. Investments, however, also have to be recouped from regulated electricity tariffs and additional risks arise from unstable regulation driven by electoral dynamics. Investment lifetimes are often very long (over 20 years), and the possibility that regulation may change during the long payback period after the investment may cause uncertainty over remuneration for the network owners.

Indeed, to address possible inefficiencies, many governments regulate such markets, for example by setting price or profit caps for the goods or services produced. Ideally, this regulation would serve the public interest, seeking efficiency in the sense of general welfare (Pigou, 1932). The eventual organization of the regulation can be influenced through political action and industry interventions, however. With an uninformed or uninterested public but a focused industry, both the setup and the implementation of the regulation may come to serve the industry rather than its consumers, leading to so-called regulatory capture (Chambers & O’Reilly, 2021; Peltzman, 2022; Stigler, 1971). In democratic societies, the public can reduce this through the political process, where legislation is determined by representatives elected through a public vote. Yet, the electoral power of consumers may be diminished by the dispersion of their votes and by collusion among the politicians who agree to impose their own policy preferences (Posner, 1974). The power of the consumer electorate to reduce collusion and affect regulation is one empirical question that we investigate in this article.

Even assuming that regulation can somehow be “optimally” set, there are potential drawbacks for investors when policies take place in a democratic environment. If elected politicians can affect regulation (for example, by changing the price cap), the democratic system inherently creates uncertainty about the future. Such uncertainty may affect long-term decisions and is particularly problematic in markets characterized by technological progress and other developments that may require substantial investments in infrastructure. It is unclear whether a regulated environment then provides proper incentives to invest (Cremer et al., 2006).

The holdup problem that arises because democratic institutions can expropriate profits through future regulation has been widely recognized (for a recent survey, see Duggan & Martinelli, 2017). One possible remedy is to introduce an independent regulator with a fixed investment-friendly policy and a mandate that spans beyond a typical political tenure. Regulatory independence may, however, increase the chance of its capture by the industry, given the industry’s increased interest in the more persistent and thus consequential regulation (Mitchener, 2007; Rajam & Ramcharan, 2016).

A regulatory mandate is politically designed. Little is known about how politically designed independence mitigates the holdup and capture problems and their interaction. This is where we aim to contribute. In particular, we investigate how independence can lead to the problem mentioned in the previous paragraph, to wit, entrenched institutional capture, the institutionalization of regulatory capture in an independent regulator.

For an analysis of the potential of the consumer electorate to influence the policy and stability of regulation as well as the resulting dynamics of investment and efficiency, it is therefore important to consider the interaction between (i) firms (like infrastructure operators), (ii) politicians that design and appoint regulatory mandates, and (iii) consumers with voting rights. Most of the existing literature has focused on the relationship between stable regulation and investment (e.g., Cambini & Rondi, 2012; Égert, 2009; Nagel & Rammerstorfer, 2008; Vogelsang, 2010; Avdasheva & Orlova, 2020; for a more complete overview see Normann & Ricciuti, 2009), or on political determinants of regulatory policies, sometimes including the influence of voters (Noll, 1989; Bischoff & Siemers, 2013). Dahm et al. (2014) investigate how firms can influence committee voting in legislatures with geographically distributed costs and benefits. Here we instead study how the interaction of all three groups of actors (i)-(iii) may affect the design of regulation and the efficiency of regulated markets.

To facilitate empirical testing, we stylize their interaction with a multi-period game between one infrastructure operator, several political policymakers competing for office, and consumers with voting rights. Between elections, the infrastructure operator chooses whether to invest in increased capacity. Such an investment may be profitable in an environment where demand increases over time. Investment is irreversible, however, and profitable only with a sufficiently high price for subsequent service provision. The consumers repeatedly elect a policymaker who may influence the regulation of the infrastructure service during her term. In the game we introduce, the complex regulation mechanisms can be reduced to simple (per unit) price regulation. Because the consumers are ignorant of the investment costs and benefits and prefer a policymaker who reduces the price, the infrastructure operator faces (political) uncertainty about future prices—and, hence, about the profitability of investments. On one hand, our game thus creates conditions where electoral competition creates a potential holdup problem. On the other hand, the holdup problem may be irrelevant if consumers fail to coordinate their voting. We provide theoretical equilibrium support for both the emergence of holdup and capture entrenchment and subject these two equilibrium predictions to a laboratory test.

We believe that the laboratory provides the preferred environment for this analysis. It facilitates the exploration of the power of the uninformed consumer electorate to influence regulation design in the limited environment with elections fully focused on the single issue of the regulation. Formal voting models can settle into multiple equilibria and selecting among them requires assumptions about voting behavior. Here, our laboratory experiment allows us to study the dynamics and efficiency of regulation with real voting behavior under controlled incentives. Importantly, none of this is possible with observational field data (Posner, 1974).

Our laboratory experiment thus allows us to investigate the impact of electoral pressure on regulation and investment with a high degree of control. For the environment studied here, this control provides major advantages that complement formal analysis and evidence from observational field studies.Footnote 3 For example, it allows us to remove the uncertainty related to the future development of infrastructural utilization and isolate the uncertainty related to the variation in future prices caused by changes in regulation (see Engel & Heine, 2017 for experimental evidence about regulation under demand uncertainty). It also allows us to systematically vary the extent to which the regulator’s interests are aligned with those of the infrastructure operator. Such control thus facilitates investigation of the effects of the regulatory framework and the regulator’s preferences under conditions that are strongly ceteris paribus.Footnote 4

The influence of policymakers is limited by a regulatory framework. We study two boundary cases: a rigid framework where the rules are set once and for all by initially elected policymakers, and a flexible framework where rules can be modified anytime. In all cases, we retain the political influence on the initial regulatory design. We examine the role of regulatory capture in each of these frameworks.

The experimental results provide some support for the comparative static predictions from the formal equilibrium analysis. With regulatory capture investment is efficient but prices are inefficiently high. The highest prices are observed under a rigid regulatory framework. This demonstrates the capture entrenchment, where investor-biased policymakers set inefficient initial prices that cannot be corrected at later points in time. A more flexible regulatory framework allows electoral competition to push prices down to benefit consumers.

In sharp contrast, we observe the holdup problem in all situations without capture. With flexible regulatory frameworks electoral competition pushes (regulated) prices down to levels that are beneficial to consumers in the short run but detrimental in the long run, because they make investment unprofitable. Here, efficient investment is observed more often with rigid regulation. We conclude that regulatory independence is beneficial when policymakers favor consumers but may be detrimental if they favor the industry.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The following section introduces our stylized model and equilibrium analysis. This is followed by our experimental design and procedures in Sect. 3. Section 4 gives our results and Sect. 5 offers a conclusion. Technical details are given in the online appendix with supplementary materials that also contain experimental instructions and additional analyses.

2 The endogenous regulation game

A simple price regulation game for a market with linear demand suffices to illustrate how inefficiencies may result from regulation that is either too strict or too lax. Our aim is not to provide a complete theoretical analysis of this market. Instead, our game can be seen as a toy model that illustrates the equilibria that may exist in the distinct environments we study. These serve to help understand how regulatory capture and regulatory flexibility might affect the market outcome. For this purpose, the model describes the behavior of policymakers and infrastructure operators, but it also includes consumer-voters, who derive utility from the service and choose policymakers based on their past and promised regulation policies. Here we provide a brief discussion of the main building blocks of the model, its key insights, and the equilibrium predictions that are relevant for our experimental design. Details are presented in Appendix A in the online supplementary materials.

Our model involves an economy with the following agents:

(IO) One infrastructure operator. It maximizes profit through its pricing, subject to regulation. IO can in addition decide to invest in its own infrastructure. Investment is costly but increases the quantity or quality of the service that the IO can provide. The IO is fully informed about the current and future market conditions.

(PMs) Several policymakers. One of them is elected to office, denoted by PME, and may then affect the price regulation of the IO’s service. The other policymakers are inactive, make no decisions and earn zero payoffs. They are fully informed about the current and future market conditions.

(CV) A set of consumers/voters. The consumers’ payoff is given by their total surplus from consuming the IO’s service. Consumers may benefit from investment because it permits increased consumption. Voters elect the PME and consume service provided by IO. They know their own payoff function, the preference alignment of the policymakers and the general interests of the IO.

We consider agents’ choices in both a regulated and an unregulated environment. Regulation involves the elected PM setting a price cap for the IO’s services to the consumers. An unregulated profit-maximizing IO charges the monopoly price and invests in the infrastructure only when it is profitable to do so (cf. Appendix A in the online supplementary materials). When the price is regulated and binding (in the sense that the IO can no longer ask the monopoly price), the IO charges the maximally permitted price. Because the regulated price is then lower than the unregulated price, regulation delays investments in the infrastructure, which may become the main source of inefficiency. On the other hand, monopoly prices are inefficiently high.

Consumers’ preferences regarding price and investment—and therefore, their preferences with respect to regulation—may also be in conflict. They prefer low prices but dislike the delayed investment. The two countervailing efficiency effects of regulation as well as the conflicting effects for consumers will be considered by policymakers when deciding on regulation. How the PMs respond depends on their own preferences.

Policymakers’ preferences are therefore a variable of interest in our model and experiment. We consider two general cases. In the first, PMs are subject to “regulatory capture.” A detailed modeling of the nature of regulatory capture is beyond the scope of this paper (see Martimort, 1999 for the dynamic view of regulatory institutions). Instead, we adopt a reduced form approach and model regulatory capture by way of variation in PMs’ preferences, which represent different supply curves in the political market for regulation (Russell & Shelton, 1974). In the case of capture, their interests coincide perfectly with those of the industry, in this case the IO. We model the case without capture by aligning PMs’ interests with those of the consumers that elect them.Footnote 5 This reduced-form approach is sufficiently general to allow for various underlying models of regulatory capture. Throughout this paper we assume that the PMs’ alignment is common knowledge.Footnote 6 Consumers, however, do not have complete information: they do not know the IO’s payoff structure. As a consequence, they do not know the PM’s payoffs when there is regulatory capture either.Footnote 7 The IO and PMs are assumed to be better informed and always know everyone’s payoffs.

2.1 The game

We describe the interaction between consumers, policymakers and investors with a simple game that consists of the following consecutive steps:

-

1.

The IO decides whether to invest. Investment costs c and eliminates capacity constraints. The optimal investment decision depends on the price cap expected in step 3.

-

2.

The CVs elect a PME using simple majority voting. The PM with a majority of votes becomes PME, where a random draw breaks ties in voting.

-

3.

The PME sets a price cap, and the IO chooses a price subject to this regulation.

To study the long-term incentives and consequences for prices and investment we study an extended game where steps 1–3 above repeat T times, with the following exceptions.

-

1.

Investment is irreversible; if the IO did not previously invest then it decides whether to do so in period t. If it invested prior to t, then IO makes no decision; it incurs costs, and all agents benefit from the increased capacity in each of the remaining periods.

-

2.

The regulatory framework may restrict how the PME may choose the maximal price. We consider two boundary regulatory frameworks.Footnote 8 In the first, regulation is flexible; the elected PME can always change the price cap chosen by its predecessor. The price regulation is therefore determined for only one period at a time. The second involves independent regulation. The first PME fixes the price cap in a way that prohibits changes by future policymakers. The PMEs elected in periods 2, …, T make no decisions.

The repeated electoral competition produces a multiplicity of equilibria, inherent in all voting environments (Banks & Duggan, 2006). We specify two boundary cases of voting behavior that represent no electoral pressure and strong electoral pressure. In Appendix A in the online supplementary materials, we characterize the corresponding perfect Bayesian equilibria (PBE) for the four environments characterized by, on the one hand, regulatory capture versus no capture, and on the other hand, flexible versus independent regulation. Table 1 briefly describes the equilibrium behavior for the two boundary cases. Specific predictions for our experimental parameters are presented.

Our cases of strong or absent electoral pressure are boundary cases of possible voting behaviors. Any other coordinated voting behavior can yield its own PBE. Given this multiplicity, the optimal regulation is ultimately an empirical matter. Our laboratory experiments serve to provide insights as to the equilibria one can expect.

3 Experimental design and procedures

3.1 General setup

The experimental design implements the model of Sect. 2 with groups of six subjects, consisting of one infrastructure operator, two policymakers and three consumers with voting rights. Groups and roles are fixed throughout the nine periods of the computerized experiment. A translation of the Dutch instructions is given in Appendix B in the online supplementary materials. In these instructions, the IO is introduced as an “investor” and the policymakers as “price determiners.” For ease of comparison, we keep here the nomenclature used in the model of the previous section. All subjects are told:

In every period, the investor delivers to each consumer a good. Exactly the same good is delivered to each consumer. Every consumer must buy the product. The price of the product is determined by one of the price determiners.

Subsequently, they are told that the investor must decide on investing in the production process and that consumers elect by majority vote which of the two policymakers will be allowed to set the price in a period. In the experiment, the set of possible prices consists of integers {0,1,2,3,4,5}.

Each of T = 9 periods then consists of six steps, which are taken sequentially:

Step I: If the IO has not previously invested, she decides whether to do so. If she has previously invested, then she makes no decision.

Step II: The IO publicly announces a desired price for the good.

Step III: The policymakers simultaneously and publicly each announce a target price for the good.Footnote 9

Step IV: Each consumer votes for one of the two policymakers. The policymaker with two or three votes is elected.

Step V: The elected policymaker sets the price for the period.Footnote 10

Step VI: Earnings are determined and each participant is informed about her own earnings in the period concerned.

Given the one-shot nature of irreversible investments we choose to have each group of subjects play this nine-period game only once. This also emphasizes the distinction between the flexible and independent regulation mandates.Footnote 11 This means that investors are inexperienced and could conceivably make errors that they would not make if they had an opportunity to learn across multiple repetitions of the game. In particular, because a decision to invest is irreversible, there may be a bias where inexperienced investors invest too early. Nevertheless, we believe that real-world investment decisions in infrastructure provide no opportunities to learn from experience and that we should maintain this characteristic in our design. Because our analysis will be based on treatment comparisons, this design choice will not affect our conclusions as long as the bias caused by inexperience is independent of treatments. One possible investor error can be easily detected. We cannot conceive of a rationalization for investing in period 1 before having observed any other choices. Below, we show that this error is made independently of treatment. Our main conclusions are barely affected by excluding or including such observations from the analysis. Though we include groups with period 1 investment in our data analyses in the main text, we provide the analyses when excluding groups with period 1 investment in Appendix F in the online supplementary materials.

3.2 Earnings

Earnings in the experiment are denoted by “experimental Franks.” At the end of a session, these are exchanged for euros at a rate of €1 for 50 Franks. Policymakers are given a starting capital of 325 Franks to avoid negative aggregate earnings. The instructions inform all subjects that additional earnings depend on (i) whether or not the IO has invested, and (ii) the price chosen by the policymaker. All subjects are subsequently told that the following general rules hold:

-

investing never harms the consumers’ earnings and often increases them;

-

higher prices are usually better for the investor;

-

lower prices are better for the consumer;

-

the policymaker that is not elected in a period earns nothing;

-

the elected policymaker earns [depends on the treatment].

The earnings of the elected policymaker shown in the last bullet depend on her preferences which differ between treatments, as will be explained below.

On their computer monitor the subjects are shown the possible earnings in a period in a table that discriminates between the six possible prices {0,1,2,3,4,5} and whether or not an investment has taken place. For each price–investment combination, the IOs and policymakers are shown the earnings of each type of participant whereas consumers see only their own earnings.Footnote 12 When subjects have finished reading the (computerized) instructions and before the experiment itself is started, they also receive a printed table showing the above payoffs for all nine periods.

The payoffs are based on the model presented in Appendix A in the online supplementary materials. Inspired by the example of electricity consumption we assume that demand increases with periods t ∈ {1,2,…,9}. Without investment, the equilibrium supply and consumer payoffs eventually become limited by capacity constraints. Investment then increases supply and payoffs for consumers. For simplicity, we permit just discrete values for the price. These cover the most interesting cases. The precise payoff tables for IOs and consumers as presented to the participants are provided in Appendix C in the online supplementary materials; payoffs of policymakers will be described below.Footnote 13

3.3 Treatments and theoretical benchmarks

The main treatment variation that we implement is two-dimensional and follows the distinctions made in the theoretical model (cf. Section 2). On one dimension we vary regulatory capture:

[NoCap] No regulatory capture. Preferences of PMs are aligned with those of consumers.

[Cap] Regulatory capture. Preferences of PMs are aligned with those of infrastructure owners.

The second dimension distinguishes between whether or not there is regulatory independence:

[RegFlex] Flexible regulation. The elected PME can always change the price chosen by its predecessor. The price regulation is therefore determined for only one period at a time.

[RegInd] Independent regulation. The first PME fixes the regulation in a way that prohibits price changes by future policymakers. In particular, only the PME elected in period 1 can choose the price which then holds for all periods. The PMEs elected in periods 2, ..., T make no decisions.

We apply a full factorial 2 × 2 between-subject design for these treatments.Footnote 14

It is then straightforward to apply our theoretical analysis to the payoffs used in the experiment. Table 2 describes the equilibrium pricing for different regulatory frameworks and PM incentives, with either no or strong electoral pressure. Price 0 leads to a loss for an IO that invests, and thus it never invests when the PME would consequently set price 0. Price 1 is the lowest that eventually rationalizes investment, which increases consumer payoffs in the long run, and in [RegInd] it also maximizes consumer surplus. An unregulated IO will favor higher prices, but these will delay investment because it takes longer for the reduced demand to exceed capacity.

As an alternative benchmark, we consider efficiency. As usual in the experimental literature we measure efficiency as the total surplus from service production and consumption, calculated as the sum of IO’s and all CVs’ profits.Footnote 15 Our efficiency benchmark determines the most efficient outcome obtainable under the restriction that no agent makes a loss in any single period (implying only that the price must be 1 or more after IO invests).Footnote 16 Table 3 shows the efficient no-loss outcomes.

A comparison of Tables 2 and 3 shows the following. In [RegFlex] the holdup occurs without the capture (this follows from the delayed investments), and also with capture under electoral pressure, but it can be overcome by regulatory independence in [RegInd]. However, while there is no holdup if the regulatory is captured and voters ignore this, this produces inefficiency from excessive prices. Regulatory independence is efficient in the absence of capture, but with capture its efficiency depends on electoral pressure.Footnote 17

As variables of interest, we consider the effects that treatment variation has on prices, investment, and welfare. As a measure of chosen prices, we will use the average price P6 across periods 1–6. Our focus on the first six periods aims to correct for possible end-game effects.Footnote 18 Note from Table 2 that no equilibrium involves investment before period 4. Differences across treatment evolve around periods 4 and 5. As a measure of investment activity, we therefore consider variable I5 that indicates whether or not investment has taken place in (or before) period 5. With electoral pressure, for example, our equilibrium analysis predicts that this will be 0 under flexible regulation and 1 under fixed regulation. Finally, to measure welfare, we need to consider that maximum surplus is attained when prices are set to zero, but that this would involve IOs making a loss (as usual in natural monopolies). As a measure of welfare loss, we therefore use the aggregate (across periods) deviation of the chosen price Pt from the “no-loss-efficiency” price (denoted by \({P}_{t}^{{\text{eff}}}\)) given in Table 3. We denote this by ΔEP. To summarize, we will use the following three variables to characterize the results:

3.4 Hypotheses

We can use Tables 2 and 3 to derive hypotheses for each of the outcome variables depicted in (1). This yields a set of nine hypotheses that depend on whether one considers the effects of regulatory capture or regulatory independence and whether the environment is characterized by no or strong electoral pressure.

In summary, the hypotheses are as follows.

3.4.1 Effects of regulatory capture

-

(1)

Regulatory capture has no effect on prices (P6) when there is strong electoral pressure; when there is no such pressure, prices are higher under regulatory capture than without capture.

-

(2)

For investments (I5), capture has no effect under strong electoral pressure; without electoral pressure capture leads to earlier investments.

-

(3)

Regulatory capture has no effect on price deviation from equilibrium (\(\Delta {\text{EP}}\)) when there is strong electoral pressure; when there is no such pressure, such deviations are larger under regulatory capture than without capture.

3.4.2 Effects of regulatory independence without regulatory capture

-

(4)

Without regulatory capture, P6 is higher with regulatory independence than with flexible regulation. This is irrespective of whether there is electoral pressure.

-

(5)

Without regulatory capture, I5 is higher with regulatory independence than with flexible regulation. This is irrespective of whether there is electoral pressure.

-

(6)

Without regulatory capture, \(\Delta {\text{EP}}\) is lower with regulatory independence than with flexible regulation. This is irrespective of whether there is electoral pressure.

3.4.3 Effects of regulatory independence with regulatory capture

-

(7)

With regulatory capture, P6 is higher with regulatory independence than with flexible regulation. This is irrespective of whether there is electoral pressure.

-

(8)

With regulatory capture, regulatory independence does not affect I5 if there is no electoral pressure; with strong electoral pressure, I5 is higher with regulatory independence than with flexible regulation.

-

(9)

With regulatory capture, when there is no electoral pressure \(\Delta {\text{EP}}\) is larger under regulatory independence than with flexible regulation; with strong electoral pressure, \(\Delta {\text{EP}}\) is smaller under regulatory independence than with flexible regulation.

Note that some of the hypotheses differ depending on what is assumed with respect to electoral pressure. In this way, our data are informative about the perceived electoral pressure and the corresponding equilibrium selection. These hypotheses are formally derived and presented in Appendix E in the online supplementary materials, where they are also directly linked to our results. In the results section below we refer to the numbering of the hypotheses presented here.

3.5 Procedures

The experiments were run at the laboratory of the Center for Research in Experimental Economics and political Decision making (CREED) at the University of Amsterdam. Subjects were recruited from the CREED subject pool, which consists of approximately 2000 students, mainly UvA undergraduates from various disciplines. A total of 351 subjects participated and earned on average €27,42 (including a €7 show-up fee). Sessions lasted between 90 and 120 min.

Each session started with computerized instructions (Appendix B in the online supplementary materials). When subjects had finished with these, a summary was handed out, as were the payoff tables. Subjects were given 5 min to study this material. Then every subject participated in a brief measurement of aversion to commitment before the main experiment started.Footnote 19 The experiment was programmed in Delphi. Before subjects were paid, they filled out a brief questionnaire soliciting background information.

4 Experimental results

When comparing means, our test results are based on Fisher–Pitman tests. More specifically, we apply permutation t-tests (Moir, 1998) with 10,000 permutations, henceforth PtT. These are nonparametric tests with higher power than parametric t-tests (Schram et al., 2019). An important advantage compared to the more commonly used rank-sum tests is that the PtT test specifically for differences in means, while rank-sum test results may be affected by differences other than in the first moments of the distributions. To take a conservative approach, all p-values reported in this section are based on two-sided tests even when the corresponding hypothesis is one-sided.

4.1 Investments in period 1

As mentioned above, we can conceive of no rationale for IOs investing in period 1. Yet, a large fraction of our IO subjects (45.8%) do so. Recall that this implies making an irreversible decision before having observed any behavior (or any cheap talk) from the other participants. The decision to invest in period 1 is statistically independent of the type of regulation (PtT; N = 59; p = 0.869) and alignment (PtT; N = 59; p > 0.999). Because investment in period 1 is never profitable (IO’s earnings are higher if she does not invest in period 1), we assume that these choices of dominated strategies are caused by inexperienced investors making errors.Footnote 20 Nevertheless, we include all observations in the analyses of investor behavior in the main text. This is because—as mentioned above—we want to maintain the real-world characteristic that investors have little or no chance to learn from experience. Appendix F in the online supplementary materials presents the results of the same analyses excluding groups where the IO invested in round 1. Importantly, the conclusions are mostly unaffected by our choice. In places where the analyses of the restricted sample do deviate from those presented here, we note the difference in the main text.

4.2 Effects of capture

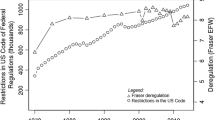

Figure 1 shows the development of prices, investments, and deviations from efficient prices across the ninr periods. The figure shows that prices are much higher (from the onset) under regulatory capture, above those suggested by the equilibrium analysis with strong electoral pressure (cf. Table 2). This suggests a weak electoral competition that is insufficient to eliminate the price effects of regulatory capture. Without capture both equilibrium analyses predict low prices, and these are indeed observed.

Our test results confirm that P6 is indeed significantly lower without capture (PtT, N = 59, p < 0.001). This supports hypothesis 1 for the case without electoral pressure. These price differences are reflected in IOs’ decisions. When they know that the PMs share their interests (in [Cap]), all IOs invest by period 5. Without capture, on the other hand, only 50% of the IOs invest by period 5, and even in the last period, 32% of the groups remain without investment. The observed difference in I5 is statistically significant (PtT, N = 59, p = 0.025), supporting the no-electoral-pressure case in hypothesis 2. Our investor subjects seem to be aware of the holdup problem without regulatory capture.

Finally, the inefficiencies with capture are reflected in the deviation from the efficient price (which is usually 1). The prices are typically (much) higher than 1 and the average deviation from the efficient price (\(\mathrm{\Delta EP}\)) is 1.93. Without capture, prices are mostly below 1, with an average deviation of 0.77 from the efficient price. The effect of capture on \(\mathrm{\Delta EP}\) is statistically significant (PtT, N = 59, p < 0.001), in support of hypothesis 3 when there is no electoral pressure.

4.3 Effects of regulation

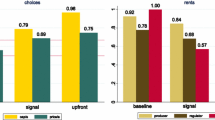

The effects of the regulatory framework are likely to depend on the policymaker’s alignment. To start, Table 4 presents an overview of our three statistics for our main treatment categories.

This suggests an interaction between alignment and regulatory framework. Below, we therefore consider the effects of regulatory independence separately, for environments with and without regulatory capture and provide PtT test results for the observed differences. First, we investigate the observed patterns in more detail. To do so, Table 5, 6, 7 presents the results of regression analyses where as independent variables we use the two treatment dummies and their interaction. The dependent variables are the three measures we use to characterize our results.

The regressions confirm the strong influence of regulatory capture. As for regulatory independence, note that the coefficient for the corresponding dummy variable describes its effects when there is no capture. It appears that in this case, such independence has a weak positive effect on prices and a strong negative effect on deviations from the efficient prices. The effect of political influence with regulatory capture is captured by the sum of the coefficients for “Regulatory Independence” and the interaction term.Footnote 21 The final row provides the (two-sided) test results on the null that there is no such effect. Our results show that with regulatory capture, installing an independent regulator sharply increases prices and deviations from the equilibrium. More generally, the results in Table 5 show that our treatment variables have various significant effects on our outcome variables. In what follows, we discuss these effects in more detail, making pairwise comparisons based on Table 4.

4.4 Regulatory independence without regulatory capture

Without capture, regulatory independence seems to have a positive impact on prices, moving them towards the efficient price level of 1 (see Table 4). This effect is significant (PtT, N = 41, p = 0.015), which is in support of hypothesis 4. The effect of regulatory independence on investments is statistically nonsignificant (PtT, N = 41, p = 0.255). We can therefore not reject a null of no investment effect in favor of our hypothesis 5. Finally, without capture prices are significantly closer to the efficient levels when there is regulatory independence than when there is not (PtT, N = 41, p < 0.001), once again supporting our hypothesis (6).

Without regulatory capture, we thus observe lower prices, delayed investment, and more efficient prices (cf. Fig. 1). This is consistent with the holdup prediction. It appears, however, that these can be manipulated by regulation. Regulatory independence leads to higher prices and lower deviations from the efficient price. These results suggest that without capture, the regulatory independence increases efficiency by facilitating more efficient pricing and investment (though the latter effect is statistically nonsignificant). It provides the IO with a guarantee that there will be no electorally-motivated future price decreases and thus eliminates the potential holdup problem that dissuades IOs from investing.

4.5 Regulatory independence with regulatory capture

With capture, regulatory independence moves prices away from the efficient price level of 1. This price effect is highly significant (PtT, N = 18, p = 0.001) and provides support for hypothesis 7.Footnote 22 Here, investments are always made by period 5, irrespective of the regulatory environment, so that we cannot formally test hypothesis 8. Finally, with capture, prices are further from the efficient levels when there is regulatory independence than when there is not. This effect is marginally significant (PtT, N = 18, p = 0.066).Footnote 23 For \(\Delta {\text{EP}}\), however, a parametric test better captures the numerically large deviations from efficient prices sometimes observed with regulatory independence. Indeed, the regressions in Table 5 (last row) show a strong significant effect.Footnote 24 This provides support for our hypothesis 9, when there is no electoral pressure.

Together, these results suggest that when there is regulatory capture, maintaining political influence on the regulator decreases prices towards the efficient price. This is consistent with the entrenchment prediction. The intuition underlying this effect is that flexible regulation allows electoral pressure to reduce the price, but independence does not. Instead, it offers the policymakers an opportunity to ensure lax regulation in the long run. Tests of the hypotheses that offer distinct predictions for the cases without electoral pressure and with strong electoral pressure (hypotheses 1, 2, 3, and 9) all provide more support for the no-pressure case. Note, however, that the prices we observe for regulatory capture are still substantially lower than predicted without electoral pressure (compare Tables 2 and 4). Electoral pressure is stronger than assumed in the no-pressure equilibrium but weaker than in the pressure equilibrium. See Appendix E in the online supplementary materials for more details on how well the equilibria with and without electoral pressure predict the patterns we observe.

In summary, the regulatory independence has opposite effects for the cases with and without capture. In the absence of capture we see that regulatory independence increases efficiency, but when there is capture such independence is detrimental.

4.6 Voting behavior

A consumer can consider the PM’s previous price choice, her announced price in the current period, both, or neither. We distinguish between first- and later-period votes. For the latter, we investigate the extent to which voters weigh currently promised prices versus previously chosen prices by the PMs.

Table 6 shows the results of a probit model explaining the probability that a consumer will vote for PM2 as opposed to PM1 (labels were randomly assigned and fixed). The results show that prior investment and period number have no effect on this decision, which is expected because neither of these variables per se is informative about future policy.Footnote 25 The relation between the PMs’ proposals and the investor’s suggestion has no effect either; the investor’s suggested price appears irrelevant. The PMs’ proposals do matter, however. In period 1, when no other information is available to the consumer, a unit increase in the proposed price difference between PM2 and PM1 decreases the probability of a PM2 vote by 34 percentage points.Footnote 26

The effect of promised price differences reduces to 12 percentage points in later periods, where consumers have information about the past actual price choices by the PMs.Footnote 27 Differences in past actual choices matter: if the last price chosen by PM2 is higher than the last price chosen by PM1, its chances of election decrease by 23 percentage points. This effect is larger than that of the equivalent difference in proposed prices.

These results show that CVs in our experiment tend to vote “rationally” in the sense that they reward PMs’ attempts to lower the price. They prefer information about actual past choices over cheap talk proposals. Nevertheless, proposals retain a small effect even when the consumers know what the PMs actually did in earlier periods. One possibility is that voters still use promises when past prices are equal, i.e., do not allow one to distinguish between the two candidates.

Next, we investigate whether CVs’ reactions to PMs depend on their alignment. Table 7 shows the probit results separately with respect to capture. Promises still have a significant effect but are more important without capture, even when evidence about past choices is available.Footnote 28The consumers appear to trust the policy promises more when policymakers are not aligned with the industry.

All in all, the disaggregated analysis in Table 7 confirms that consumers attempt to pressure the PMs through voting. They take into account that the PM’s interests are likely to affect the prices and adjust the weight they attach to promises and previous prices. In theory (cf. Table 3) regulatory capture should not matter when there is electoral pressure. In experiments, we find that capture has a major influence on prices, however. This indicates that PMs aligned with the IOs are not affected by the pressure in the way the theory assumes.

Our data from flexible regulation treatments hint at possible explanations for this. With capture and across all periods, many PMs that are elected for the first time choose the same or a higher price than the previous PM. Specifically, only 36% of newly elected PMs choose to decrease the price chosen by the other PM in the previous period, and 24% even increase this price. Note that the voting behavior analyzed in Tables 5 and 6 suggests that a “competitive” PM should reduce prices to increase her likelihood of reelection. Our observations thus suggest some extent of tacit collusion amongst PMs that allows them to mitigate the effects of electoral pressure.

5 Conclusions

Large infrastructure is often owned by private investors with the right to charge usage fees. In industries such as power or gas delivery, the privatized transmission infrastructure gives rise to natural monopolies where price regulation is necessary for efficiency. Strict regulation may, however, be detrimental to the large investments that this infrastructure requires. Periodic upgrades to the transmission infrastructure may require significant irreversible investment with long-term return spanning several decades. Investors face uncertainty in their return in many dimensions: from highly unpredictable shifts in future demand to shifts in technology. In this paper we investigate another type of uncertainty, arising from unpredictable changes in price regulation when regulators are subject to electoral competition.

Our model of investment in markets where regulation is subject to political manipulation confirms that regulatory autonomy is important for efficient investment decisions. This is especially the case when policymakers are motivated by the consumers’ interests and would, under electoral pressure, reduce prices to levels that are too low for profitable investment. Our formal and experimental results confirm that a regulator can mitigate this holdup problem when it is granted independence from political decision-making, reducing both the price inefficiency and the investment delay. For instance, regulatory independence makes it more than twice as likely that there will be timely investment in our experiment.

The situation is reversed when policymakers are motivated by the interests of the industry, i.e., when there is regulatory capture. Investment can then be timely, but regulation may be too lax, leading to inefficient price inflation. Our results show that in this case the regulatory autonomy aggravates the problem and leads to capture entrenchment because it removes the electoral pressure to reduce the prices. Even when price regulation drives voting we observe some tacit collusion between the policymakers. However, the independent regulation is even less efficient, leading to more than 80% higher prices.

Our results thus highlight the limits of the public interest theory intuition that an independent regulator is beneficial for the consumers. This holds only when electoral pressure is strong or regulation policy is designed with the interests of the consumers in mind. However, if the regulatory interests align with infrastructure operators, a flexible regulator may be more efficient. This complements the view of the economic theory of regulation (e.g., Martimort, 1999) that agencies if left alone align with industry over time as the public attention declines. One reason, our results show, is collusion by policymakers, who are able to avoid the electoral pressure to lower the prices even in a simple experimental election. Note that we observed such electoral pressure in a group with just three voters and a single electoral issue. The electoral pressure in our experiment may be an upper bound for the pressure in real elections where large voter groups select among candidates by a multitude of electoral issues.

Notes

A prime example is the privatization of railways, where responsibility for the railway infrastructure is typically allocated to a different company than those who transport passengers and freight (Cox et al., 2002). For a discussion of the effects of electoral competition in this context, see Ponti and Erba (2002).

Micro-CHP involves a combined generation of heat and power. It allows, for example, a household that uses natural gas for heating to generate electricity as a by-product. If it generates more than it uses, it can supply electricity to the network.

Falk and Heckman (2009) provide a methodological discussion of the advantages and disadvantages of laboratory experiments. An additional advantage is the possibility of replication of results.

Laboratory control has made experiments a popular method for studying issues related to various markets (e.g., Brunner et al., 2010), including electric power markets (Rassenti et al., 2002; Staropoli & Jullien, 2006; Brandts & Schram, 2008; Brandts et al., 2014). Normann and Ricciuti (2009) provide an overview of the contributions of studies using laboratory experiments to economic policymaking. One of the broad areas they discuss is the regulation of markets.

In the experiment, we also consider a third case where PMs are motivated by office rents. Our results show no significant differences between the two non-capture scenarios. An alternative case would be that PMs’ interests are aligned with total surplus. We do not consider this case of a benevolent dictator in the current paper because it would rely on artificial welfare comparisons, but we do see it as a possibility for future research.

Voters generally do have ideas about politicians’ motives, which are revealed through past policies. Note that the two alignment cases are chosen so as to compare extreme situations. In reality, regulatory capture seems the more likely scenario (Enikolopov, 2012). Because a natural choice for a politician’s post career employment is in industry, an IO will typically have much more effective lobbying power than CVs, and an IO has a strong incentive to offer future benefits (e.g., employment) to the PM. Infrastructure is also often owned by local councils, such as is the case for transmission networks in the Netherlands.

In our experiment the consumers know the IO’s interests in general terms only. We explain this below.

Rather than a faithful reproduction of an existing regulation, these two cases cover the boundary benchmarks. This facilitates clear identification of the effect of regulatory variance. The regulation in real markets typically involves a combination of our rules and rarely imposes a single price. For example, the actual regulation of electricity transmission charges in the Netherlands determines how the maximum charge changes with the consumer price index (CPI). Evidence from transmission charges in the Netherlands shows that network operators almost always charge the maximally possible price, however. We simplify this in our model by assuming a constant CPI. This leads to regulation with a constant regulated price, which we consider in our model. Moreover, we choose not to include the possibility of a “regulatory holiday” (Gans & King, 2003a, 2003b, 2004) where the IO would be exempt from the price cap for a prespecified number of periods if she invests. One reason is that in a setting without competition like ours, the holiday would involve monopoly pricing. The IO may then delay investment to optimize the period in which monopoly profits can be reaped. Evidence of such welfare-reducing behavior is found in a controlled laboratory environment by Henze et al. (2012).

Steps II and III are cheap talk and do not imply any kind of commitment. They are included for reason of external validity and do not affect the theoretical results summarized in Sect. 2.

A rational IO without other-regarding preferences will always choose the maximally regulated price with strict regulation, but a PM can regulate the price to the monopoly price. We therefore skip the IO pricing decision and assume that IO always chooses the regulated price. As a result, in the experiment the price is effectively chosen by the elected PME. In some treatments, the price is fixed across periods. In these cases, no choice is required in step V.

By repeating the experiment, the policymakers would be able to repeatedly regulate prices even for independent regulation.

This asymmetry was chosen for external validity reasons. We doubt that most consumers know the details about the consequences of specific price–investment combinations, instead relying on general notions such as “high prices are good for producers.” Producers and politicians are generally better informed.

During the experiment, the subjects also have access to a “calculation aid” on their monitor, with which they can calculate the payoff consequences of all possible combinations of prices and investments in the remaining periods. See the instructions in Appendix B for more information.

We implemented a more refined classification of treatments than presented here. Appendix D describes this in detail and shows that pooling to the level presented here has no theoretical consequences and is empirically justified.

In this literature, surplus maximization is generally preferred over the more restrictive measure of Pareto efficiency (e.g., Smith, 1994; Rasenti et al., 2002). Allocation A is then more efficient than allocation B if total earnings are higher in A, even if some individuals earn less in A than in B.

This represents the textbook case of average cost pricing.

For the sake of completeness, we consider the inequality involved in the various outcomes. Before investment, the most equal payoffs are obtained with price sequence {2,2,3,3,3,3,4,4,4}, but after investment the payoffs are most equal when P = 2 in all periods.

This provides a conservative approach because we will see when presenting the results that average price differences are larger across all periods (cf. Fig. 1).

The results of the commitment measurement proved uninformative for behavior in the main experiment and will not be discussed in this paper.

Alternatively, IOs may invest in the (mistaken) expectation that this will be reciprocated by PMs choosing high prices. This too, may be considered an error.

The effect of having regulatory independence and regulatory capture on the dependent variables is given by the sum of the three coefficients; the effect with flexible regulation and regulatory capture is given by the capture dummy; the difference (the sum of the coefficients for “Flexible Regulation” and the interaction term) thus gives the effect of regulatory independence when there is regulatory capture.

This price difference is significant at the 10% level in the restricted sample of Appendix F.

This result is nonsignificant in Appendix F in the online supplementary materials (p = 0.415).

This effect is marginally significant (p = 0.07) for the restricted sample.

The result that investment does not significantly affect voters’ choices provides support for our choice to use the full data set in this analysis of voter behavior.

These marginal effects are determined at the mean values of the independent variables. They are not constant. Hence, this estimated value should not be taken to imply that large differences in proposed prices would yield percentage point differences of more than 100%.

The benchmark for the three dummy variables related to actual previous choices is the situation where one of the PMs has not yet been elected in an earlier period.

The statistical power for the effects of actual relative previous choices is low for some of the significance tests because PMs often agree on what price to choose. For example, for the case with capture, we have only 12 observations where the most recent price chosen by PM1 is larger than that chosen by PM2 (i.e., LastP2lower = 1). Taking this into account, we can draw only tentative conclusions from the tests that do have sufficient power.

References

Avdasheva, S., & Orlova, Y. (2020). Effects of long-term tariff regulation on investments under low credibility of rules: Rate-of-return and price cap in Russian electricity grids. Energy Policy, 138, 111276.

Banks, J., & Duggan, J. (2006). A general bargaining model of legislative policy-making. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 1, 49–85.

Bischoff, I., & Siemers, L. H. R. (2013). Biased beliefs and retrospective voting: Why democracies choose mediocre policies. Public Choice, 156, 163–180.

Brandts, J., Pezanis-Christou, P., & Schram, A. (2008). Competition with forward contracts: a laboratory analysis motivated by electricity market design. The Economic Journal, 118, 192–214.

Brandts, J., Reynolds, S. S., & Schram, A. (2014). Pivotal suppliers and market power in experimental supply function competition. The Economic Journal, 124(579), 887–916.

Brunner, C., Goeree, J. K., Holt, C. A., & Ledyard, J. O. (2010). An experimental test of flexible combinatorial spectrum auction formats. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 2(1), 39–57.

Cambini, C., & Rondi, L. (2012). Incentive regulation and investment: Evidence from European energy utilities. Journal of Regulatory Economics, 38, 1–26.

Campillo, J., Wallin, F., & Dahlquist, E. (2012). “Electricity demand impact from increased use of ground sourced heat pumps”, paper presented at the 3rd IEEE Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Europe.

Chambers, D., & O’Reilly, C. (2021). The economic theory of regulation and inequality. Public Choice. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-021-00922-w

Cox, J., Offerman, T., Olson, M., & Schram, A. (2002). Competition for vs on the rails, a laboratory experiment. International Economic Review, 43, 709–735.

Cremer, H., Crémer, J., & De Donder, P. (2006). Legal vs ownership unbundling in network industries. CEPR Discussion p. 5767

Dahm, M., Dur, R., & Glazer, A. (2014). How a firm can induce legislators to adopt a bad policy. Public Choice, 159, 63–82.

Duggan, J., & Martinelli, C. (2017). The political economy of dynamic elections: Accountability, commitment, and responsiveness. Journal of Economic Literature, 55, 916–984.

Égert, B. (2009). Infrastructure investment in network industries: The role of incentive regulation and regulatory independence. CESifo working p. 2642

Engel, C., & Heine, K. (2017). The dark side of price cap regulation: A laboratory experiment. Public Choice, 173, 217–240.

Enikolopov, R. (2014). Politicians, bureaucrats and targeted redistribution. Journal of Public Economics, 120, 74–83. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.945274

Falk, A., & Heckman, J. (2009). Lab experiments are a major source of knowledge in the social sciences. Science, 326, 535–538.

Gans, J., & King, S. (2003a). Access holidays for network infrastructure investment. Agenda, 10, 163–178.

Gans, J., & King, S. (2003b). Access holidays and the timing of infrastructure investment. Economic Record, 80, 89–100.

Henze, B., Noussair, Ch., & Willems, B. (2012). Regulation of network infrastructure investments: An experimental evaluation. Journal of Regulatory Economics, 42, 1–38.

Kessides, I. N. (2004). Reforming infrastructure: Privatization, regulation, and competition. World Bank Publications.

Klein, M. and Gray Ph. (1997), Competition in Network Industries—Where and How to Introduce it, Public Policy for the Private Sector Note 104, World Bank.

Knobloch, F., Hanssen, S. V., Lam, A., Pollitt, H., Salas, P., Chewpreecha, U., & Mercure, J. F. (2020). Net emission reductions from electric cars and heat pumps in 59 world regions over time. Nature Sustainability, 3(6), 437–447.

Martimort, D. (1999). The life cycle of regulatory agencies: Dynamic capture and transaction costs. The Review of Economic Studies, 66(4), 929–947.

Mitchener, K. J. (2007). Are prudential supervision and regulation pillars of financial stability? Evidence from the great depression. The Journal of Law and Economics, 50(2), 273–302.

Moir, R. (1998). A Monte Carlo analysis of the Fischer randomization technique: reviving randomization for experimental economists. Experimental Economics, 1, 87–100.

Nagel, T., & Rammerstorfer, M. (2008). Price Cap Regulation and investment behavior–how real options can explain underinvestment. Journal of Energy Markets, 1, 23–45.

Normann, H.-T., & Ricciuti, R. (2009). Laboratory experiments for economic policy making. Journal of Economic Surveys, 23, 407–432.

Peltzman, S. (2022). The theory of economic regulation after 50 years. Public Choice. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-022-00996-0

Pigou, A. C. (1932): The economics of welfare. London: Macmillan (4th edition).

Ponti, M., & Erba, S. (2002). Railway liberalization from a “public choice” perspective. Quarterly Journal of Transport Law, Economics and Engineering VII, 20–21, 38–46.

Rajam, R. G., & Ramcharan, R. (2016). Constituencies and legislation: the fight over the McFadden Act of 1927. Management Science, 62(7), 1843–1859.

Rassenti, S., Smith V., Wilson B. (2002): Using experiments to inform the privatization/deregulation movement in electricity, The Cato Journal, 22, 3, winter 2002.

Russell, M., & Shelton, R. B. (1974). A model of regulatory agency behavior. Public Choice, 20, 47–62.

Schram, A., Brandts, J., & Gërxhani, K. (2019). Status ranking: a hidden channel to gender inequality under competition. Experimental Economics, 22(2), 396–418.

Smith, V. (1994). Economics in the Laboratory. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 8, 113–131.

Staropoli, C., & Jullien, C. (2006). Using laboratory experiments to design efficient market institutions: the case of wholesale electricity markets. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 77(4), 555–577.

Stigler, G. J. (1971). The theory of economic regulation. The Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science, 2(1), 3–21.

van Vliet, O., Brouwer, A., Kuramochi, T., van den Broek, M., & Faaij, A. (2011). Energy use, cost and CO2 emissions of electric cars. Journal of Power Sources, 196(4), 2298–2310.

Vogelsang, I. (2010): Incentive regulation, investments and technological change, CESifo working p. 2964

Acknowledgements

The research in this paper was funded by the CPB in Den Haag. We are grateful to Rob Aalbers, Victoria Shestalova, and Gijsbert Zwart of the CPB for useful suggestions at various stages of the research project. We are also indebted to Sander Onderstal for comments on an earlier draft of this paper. This paper has also benefited from useful comments by two anonymous reviewers. All data used in this paper are available from the authors upon request. Both authors contributed equally to this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schram, A., Ule, A. Regulatory independence may limit electoral holdup but entrench capture. Public Choice 198, 403–425 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-023-01136-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-023-01136-y