Abstract

I show that a state representative’s political party determines transportation expenditure in the area she represents. Previous studies of this topic consider party changes through election outcomes, which may be correlated with unobservable determinants of expenditure. To overcome this issue, I identify my estimates using Ohio’s 2012 state legislative redistricting, which moved many geographic areas into districts with opposite party incumbents. The Republican party controlled the state legislature and governorship over the period I study. I find that areas moving from governing party Republican to minority party Democratic districts received $3.4M (0.18 standard deviations) less annual highway construction funding than areas remaining in Republican districts. Areas moving from a Democratic to a Republican district, on the other hand, experienced no increase in expenditure—the negative effect of moving to a different representative’s district appears to outweigh the positive effect of a majority party representative. Descriptive evidence suggests that changing representative’s party through redistricting had a different effect on construction funding than changing through an election, underlining the importance of my identification strategy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The state of Ohio spent $3.07 billion on highways and roads in 2014, the majority of $5.41 billion state and local spending on roads and highways in the state. This included the bulk of capital expenditure ($2.41 billion out of $3.19 billion). Throughout the US, states undertook 59% of expenditure on highways (57% in Ohio), including 73% of capital expenditure (76% in Ohio). (United States Census Bureau 2014).

States with an entirely Democratic delegation received only 17% more when Democrats controlled the Senate, House, and presidency.

I derive each intersection between new and old districts by spatially joining 2003–2012 district shapefiles and 2013–2022 district shapefiles (United States Census Bureau 2013) using ArcMap10.1 GIS software. In addition to very small areas that may have derived from measurement error, I also dropped 15 areas with population over 100 but missing control variables. More details on sample construction are in Online Appendix A.

To calculate the population of each area of intersection, I spatially joined the TIGER/Line shapefile of 2010 Ohio Census blocks (United States Census Bureau 2011) to the joined shapefiles of the 2003–2012 and the 2013–2022 districts (United States Census Bureau 2013). Then I summed the population of all Census blocks overlapping each area of intersection to calculate the entire population of each area of intersection.

Two incumbents lost in a general election, one lost his primary, and 17 incumbent representatives did not run for reelection. Another representative ran for reelection in a different district that did not overlap with her old district. Six of the representatives who did not run were term limited, one held the office in place of a different representative who had joined the governor’s cabinet, and one resigned while facing corruption charges. Thus, only seven representatives chose not to run voluntarily.

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act also prohibits diluting racial minorities’ votes through gerrymander. As interpreted in Thornburg v. Gingles (1986), Section 2 requires that majority-minority districts must be formed when a racial minority votes as a bloc and is concentrated enough to be grouped into one district.

Details on this process are available in Online Appendix A.

From 1997 to 2012 the cut-off was $5 M. In 2012 the legislature raised it in accordance with the ODOT’s estimation of increased costs.

The two Democratic representatives who broke ranks and supported the bill represented Districts 10 and 12, located near an alternate route for the Ohio Turnpike (Interstate 90). Under the Plan, District 10 (Cleveland) benefited from two improvements to I-90 worth over $650 million, and District 12 (Warrensville Heights) benefited from $200 million of widening work on I-271.

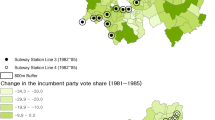

For reference, I have summarized all variables at the house district level in Table A of the Online Appendix. Total expenditure remains almost the same between Republican and Democratic districts, but Republican districts receive more projects. This likely reflects Republican districts’ location in more rural areas (see Fig. 2) Because rural areas contain more road mileage but fewer bridges and intersections, Republican districts receive more small projects and fewer large projects.

These are new construction, intersection or interchange work, widening, miscellaneous projects, and bridge repair. Miscellaneous projects includes all projects that could not easily be classified including section improvement, intelligent vehicle systems, building demolition, and realignment or relocation.

Estimates of employment and employed population are available from the Longitudinal Employer Household Dynamics project of the Census Bureau (United States Census Bureau 2015) at the Census block level. I use years 2006–2015 which provide a lagged value for each year in my 2007–2016 sample. To calculate the employment and employed population of each area of intersection, I first spatially joined the TIGER/Line shapefile of 2010 Ohio Census blocks (United States Census Bureau 2011) to the areas of intersection formed by joined shapefiles of the 2003–2012 and the 2013–2022 districts (United States Census Bureau 2013). Then I merged the area of intersection-by-Census block pairings to the LEHD block-level data. Finally, I summed the employment and employed population of all Census blocks overlapping each area of intersection to calculate these variables, as summarized in Table 2.

Republican districts had slightly higher population in 2010 than Democratic districts. More areas shifted from Republican to Democratic districts than vice versa, despite Republicans picking up one more seat: the redistricting process needed to add population to Democratic districts.

Throughout this section, when I refer to party transitions, or to R to D, D to R, etc., I refer only to transitions during the redistricting year.

See Sect. 3.2. I control for lagged covariates, rather than contemporaneous values, to avoid problems of reverse causality. For example, better roads in an area may increase traffic or vehicle ownership among residents. In spite of this, I am concerned that local funding of road construction in particular may be determined by unobservable changes in state spending. I estimate the specifications in Columns 2, 3, 5, and 7 without local funding covariates in Online Appendix Table B1, and without locally sponsored projects in the outcome variable in Online Appendix Table B2. Results are similar to those in Table 4.

The positive coefficients on “GOP Representative, Dem. Gov.” and “Dem. Representative, GOP Gov.” suggests no advantage from belonging to the Democratic party in years with Democratic governor’s party. The single-term Democratic governor during my sample, Ted Strickland (2007–2010), likely possessed less political clout than his predecessors or successors. Governor Strickland followed 16 years of Republican governors, and faced a largely Republican-controlled Assembly (see Fig. 1). Some decision makers in the ODOT were appointed by his predecessors, including most of the TRAC: Governor Strickland appointed only two members to this committee during his term. At the same time, these estimates should not be interpreted as causal, and may reflect characteristics of the type districts selecting representatives from a different party than the governor.

The pre-2011 party change indicators, e.g. (R to D)\(\times\)(year < 2011), are not included because I am controlling for party and alignment with the governor in each year.

There are two other party change mechanisms. First, the incumbent could lose the primary, with her rival losing the general election. Among the ten incumbents who lost their primary reelection between 2007 and 2016, each candidate who beat the incumbent in the primary won the general election. Second, in 41 year-by-district observations the representative left office during her term (usually after an appointment to a preferable office, due to a scandal, or due to unexpected death). I consider the appointed replacement as the incumbent.

References

Albouy D (2013) Partisan representation in congress and the geographic distribution of federal funds. Rev Econ Stati 95(1):127–141

Ansolabehere S, Snyder JM, Stewart C (2000) Old voters, new voters, and the personal vote: using redistricting to measure the incumbency advantage. Am J Polit Sci 44(1):17–34

Ansolabehere S, Snyder JM Jr (2006) Party control of state government and the distribution of public expenditures. Scand J Econ 108(4):547–569

Balla S, Lawrence E, Maltzman F, Sigelman L (2002) Partisanship, blame avoidance, and the distribution of legislative pork. Am J Polit Sci 46(3):515–525

Bernhardt D, Dubey S, Hughson E (2004) Term limits and pork barrel politics. J Publ Econ 88:2383–2422

Berry CR, Burder BC, Howell WG (2010) The president and the distribution of federal spending. Am Polit Sci Rev 104(4):783–799

Boyle M, Matheson V (2009) Determinants of the distribution of congressional earmarks across states. Econ Lett 104(2):63–65

Bracco E, Lockwood B, Porcelli F, Redoano M (2015) Intergovernmental grants as signals and the alignment effect: theory and evidence. J Public Econ 123:78–91

Case A (2001) Election goals and income redistribution: recent evidence from Albania. Eur Econ Rev 45(3):405–423

Castells A, Solé-Ollé A (2005) The regional allocation of infrastructure investment: the role of equity, efficiency and political factors. Eur Econ Rev 49(5):1165–1205

Chen J (2010) The effect of electoral geography on pork barreling in bicameral legislatures. Am J Polit Sci 54(2):301–322

Daley D (2016) Ratf****d: The True Story Behind the Secret Plan to Steal America’s Birthright. Liveright, New York

Denemark D (2000) Partisan pork barrel in parliamentary systems: Australian constituency-level grants. J Polit 62(3):896–915

Dirossi R (2012) Dirossi affidavit with all exhibits. Accessed 15 Sept 2023 from https://www.supremecourt.ohio.gov/pdf_viewer/pdf_viewer.aspx?pdf=700679.pdf &subdirectory=2012-0019%5CDocketItems &source=DL_Clerk

Dixit A, Londregan J (1998) Ideology, tactics, and efficiency in redistributive politics. Quarter J Econ 113(2):497–529

Draper R (2012, October) The league of dangerous mapmakers. The Atlantic. Accessed 11 Sept 2023 from https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2012/10/the-league-of/309084/

Federal Highway Administration (2017) Bridge condition by county. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/bridge/britab.cfm

Fields R (2011) Gov. John Kasich moves ahead with turnpike leasing proposal. Cleveland.com. Accessed 18 Jun 2019 from https://www.cleveland.com/open/2011/08/gov_john_kasich_moves_ahead_wi.html

Fisher R (2016) State and local government finance, 4th edn. Routledge, New York

Friedman JN, Holden RT (2008) Optimal gerrymandering: sometimes Pack, but Never Crack. Am Econ Rev 98(1):113–44

Gambale G (2016) 31st annual survey of corporate executives: cautious optimism reflected. http://www.areadevelopment.com/Corporate-Consultants-Survey-Results/Q1-2016/corporate-executive-site-selection-facility-plans-441729.shtml

Gambale G (2017) 31st Annual survey of corporate executives: confidence in U.S. economy, need for investment in infrastructure reflected. http://www.areadevelopment.com/Corporate-Consultants-Survey-Results

Gilligan TW, Matsusaka JG (1999) Structural Constraints on Partisan Bias under the Efficient Gerrymander. Public Choice 100(1):65–84

Gul F, Pesendorfer W (2010) Strategic redistricting. Am Econ Rev 100(4):1616–1641

Jacques O, Ferland B (2021) Distributive politics in canada: the case of infrastructure spending in rural and suburban districts. Canad J Polit Sci 54(1):96–117

Joanis M (2011) The road to power: partisan loyalty and the centralized provision of local infrastructure. Public Choice 146:117–143

Johansson E (2003) Intergovernmental grants as a tactical instrument: empirical evidence from Swedish municipalities. J Publ Econ 87(5):883–915

Larcinese V, Rizzo L, Testa C (2006) Allocating the U.S. federal budget to the states: the impact of the president. J Polit 68(2):447–456

Levitt SD, Snyder JM, Jr, (1995) Political parties and the distribution of federal outlays. Am J Poli Sci, 958–980

Mehiriz K (2015) The influence of redistributive politics on the decision making of quasi-autonomous organizations. The case of infrastructures-transport (quebec-canada). J Publ Admin Res Theory 25(4):1081–1098

Milligan KS, Smart M (2005) Regional grants as pork barrel politics. Available at SSRN 710903

Morgenstern S, Swindle SM (2005) Are politics local? An analysis of voting patterns in 23 democracies. Compar Polit Stud 38(2):143–170

Newkirk V (2017) How redistricting became a technological arms race. The Atlantic. Accessed 11 Sept 2023 from https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2017/10/gerrymandering-technology-redmap-2020/543888/

Ohio Department of Taxation (2016) Tax data series. https://tax.ohio.gov/researcher/tax-data-seriesl

Ohio Department of Transportation (2017) Daily vehicle miles traveled (dvmt). https://www.transportation.ohio.gov/programs/technical-services/traffic-monitoring/dvmt

Ohio Secretary of State (2017) Election results and data. https://www.ohiosos.gov/elections/election-results-and-data/

Owen G, Grofman B (1988) Optimal Partisan Gerrymandering. Politic Geogr Quar 7(1):5–22

Pierre-Louis L (2012) Appendix of exhibits to affidavit of Lloyd Pierre-Louis. Accessed 11 Sept 2023 from https://law.osu.edu/electionlaw/litigation/documents/app1.pdf

Provance J (2013) House oks \$1.5b plan for turnpike borrowing, bill expected to get to kasich’s desk. Toledo Blade. Accessed 18 Jun 2019 from https://www.toledoblade.com/news/state/2013/03/01/House-OKs-1-5B-plan-for-turnpike-borrowing-bill-expected-to-get-to-Kasich-s-desk/stories/feed/index.rss

Provance J (2019) Once heralded, borrowing against ohio turnpike now called ‘irresponsible to continue’. Toledo Blade. Accessed 18 Jun 2019 from https://www.toledoblade.com/local/transportation/2019/02/21/turnpike-borrowing-road-construction-called-irresponsible/stories/20190215137

Raina S, Xu SJ (2021) The effects of voter partisanship on economic redistribution: Evidence from gerrymandering. Technical Report SSRN Research Paper No. 2019-505

Sabouni H, Shelton C (2021) State legislative redistricting: the effectiveness of traditional districting principles in the 2010 wave. Elect Law J Rules Polit Policy 20(2):198–214

Sabouni H, Shelton CA (2022) Gerrymandering in state legislatures: frictions from axiomatic bargaining. Am Econ J Econ Policy 14(4):519–542

Sherstyuk K (1998) How to Gerrymander: a formal analysis. Public Choice 95(1):27–49

Shugart MS (1999) Presidentialism, parliamentarism, and the provision of collective goods in less-developed countries. Constit Polit Econ 10(1):53–88

Smothers D (2013) Can you ever beat the board-challenges to legislative reapportionment in ohio after wilson v. kasich. U. Cin. L. Rev. 82, 979

Solé-Ollé A, Sorribas-Navarro P (2008) The effects of partisan alignment on the allocation of intergovernmental transfers. Differences-in-differences estimates for Spain. J Public Econ 92(12):2302–2319

Tavits M (2009) Geographically targeted spending: exploring the electoral strategies of incumbent governments. Eur Polit Sci Rev 1(1):103–123

Thornburg v. Gingles (1986) 478 U.S. 30 (1986)

United States Census Bureau (2011) 2010 TIGER/Line Shapefiles Special Release - Census Blocks with Population and Housing Counts. https://www2.census.gov/geo/tiger/TIGER2010BLKPOPHU/

United States Census Bureau (2013) 2013 TIGER/Line Shapefiles. https://www2.census.gov/geo/tiger/TIGER2013/

United States Census Bureau (2014) Annual surveys of state and local government finances, and census of governments: finance, (2014). https://www.census.gov/govs/local/historical_data.html

United States Census Bureau (2015) Annual surveys of state and local government finances, and census of governments: finance, (2015). https://www.census.gov/govs/local/

United States Census Bureau (2017) LEHD origin destination employment statistics, version 7.3. https://lehd.ces.census.gov/data/#lodes

Wilson v. Kasich (2012) 134 Ohio St. 3d 221, 2012-Ohio-5367

Wokker C (2019) Marginal benefits? Electoral geography and economic outcomes, technical report, tax and transfer policy Institute

Wooldridge J (2010) Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data, 2nd edn. The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Wu Y, Williams D (2015) State legislative earmarks: counterparts of congressional earmarks? State Local Govern Rev 47(2):83–91

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

WM completed all authorship tasks associated with the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

I have benefited from discussions with Mike Conlin, Leslie Papke, and Ron Fisher, and from participants at the 111th Annual Conference of the National Tax Association and the University of Wisconsin Milwaukee Labor Lunch. I also thank the editor, Marko Köthenbürger, and two referees who provided thoughtful and helpful comments. None of the above bear responsibility for remaining errors.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Melnik, W. Legislative redistricting and the partisan distribution of transportation expenditure. Econ Gov 25, 1–29 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10101-024-00308-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10101-024-00308-w