Abstract

This study examines the relationship between macroeconomic uncertainty and earnings management, using quarterly data of US commodity firms from the period 1990–2019. The findings show that oil and iron firms use both accruals and real activities to decrease earnings in quarters with high basis risk. Earnings management is economically significant. Further investigation provides fine-grained evidence that specific types of uncertainty (economic policy, climate policy, geopolitical) have varying effects on earnings management. The study also provides evidence that earnings management is aimed at giving investors useful information about the firms’ performance during uncertain times. The study contributes to previous research on uncertainty and earnings management. It also informs market participants about the financial reporting quality of commodity firms, and has practical implications for financial reporting regulation in extracting industries.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Prior studies highlight that chief financial officers (CFOs) estimate that business model, industry-wide, and economy-wide factors account for most of the earnings quality in external reporting, with quality earnings defined as being “sustainable and repeatable” (Dichev et al. 2013, p. 1). Researchers examine the influence of the macroeconomy on earnings management by investigating economic crises (Filip and Raffournier 2014; Trombetta and Imperatore 2014). Recent studies focus on economic policy uncertainty and earnings management (El Ghoul et al. 2021; Bermpei et al. 2022). Drawing on Kirschenheiter and Melumad (2002) theoretical model of financial reporting, we investigate the relationship between macroeconomic uncertaintyFootnote 1 and earnings management, decomposing the former into economic policy, geopolitical, and climate policy uncertainty (Baker et al. 2016; Caldara and Iacoviello 2022; Gavriilidis 2021). We also study whether earnings management in response to uncertainty has a signalling or garbling effect for the external users of financial reports.

This research is motivated by two factors. First, in recent years, geopolitical uncertainty related to events such as the Ukraine war, US-China tensions over Taiwan, and uncertainty related to climate change are surging (Ahir et al. 2022; Altig et al. 2020). Hence, a thorough study on the dimensions of uncertainty could be informative for academics and practitioners regarding the quality of financial reporting in the current and future business environment. Also, prior research provide mixed evidence suggesting either income-decreasing and income-increasing earnings management in more uncertain period (e.g. Bermpei et al. 2022; Chauhan and Jaiswall 2023). We use Kirschenheiter and Melumad (2002) theoretical model to make predictions on the relationship between earnings management and uncertainty, based on how the manager’s assessment of the external economic and market conditions determine the financial reporting strategy.

Second, prior research has not thoroughly investigated whether earnings management motivated by uncertainty makes earnings more or less informative for external users of financial reports. Managers use earnings management for signaling purposes when they want to increase earnings informativeness and help investors predict future earnings (Baik et al. 2020). They can also opportunistically use earnings management for job security and compensation reasons (DeFond and Park 1997; Graham et al. 2005). Uncertainty may exacerbate both these motivations. Ng et al. (2020) find that banks facing policy uncertainty increase their loan loss provision to signal expected loan losses. In this paper, we aim to understand whether earnings management under uncertainty signals or garbles the firm’s performance, by looking at earnings informativeness for stock markets.

To investigate our research questions, we select the commodity firms setting. This setting is interesting for several reasons. First, for most firms, macroeconomic uncertainty reduces revenues and prompts cost-cutting activity in most industries (Binz 2022). However, the effect of macroeconomic uncertainty on earnings management in commodity firms is ex ante ambiguous. In uncertain periods, depending on the nature of the uncertainty, prices of raw materials may decrease, but they may also increase, boosting the revenues and profits of commodity firms (Damodaran 2009; Dayanandan and Donker 2011; Salerno 2017). In addition, unlike other firms, commodity firms have high fixed costs (such as depreciation and salaries), which may make timely cost-cutting activity harder in uncertain times. Also, unlike other industries, commodity firms are exposed to several types of uncertainty and are strongly exposed to climate policy uncertainty, a type of uncertainty that has surged in recent years. It is thus an ideal setting for a study on specific types of uncertainty. Second, recent research calls for studies on the financial reporting of commodity firms because of their huge stock values; the wide political, environmental, and social implications of their activities; and the challenges in measuring operations and defining industry-specific accounting standards (Gray et al. 2019).

As a proxy for future uncertainty, we use the basis risk, i.e., the spread between the commodity current price and the future (Bailey and Chan 1993; Watugala 2019; Bakas & Triantafyllou 2019). As an alternative measure, we also use the VIX (Berger et al. 2020). We also decompose the overall macroeconomic uncertainty in economic policy, geopolitical and climate uncertainty (Baker et al. 2016; Caldara and Iacoviello 2022; Gavriilidis 2021). We use financial quarterly data from US oil and iron producer firms over the period spanning from 1990 Q1 to 2019 Q4. Quarterly data are suitable for our study on earnings management as macroeconomic uncertainty maps onto revenues and profits on a quarterly basis in commodity firms (Han and Wang 1998; Diebold and Yilmaz 2008; Hsiao et al. 2016). The main analysis investigates both accrual and real earnings management using a single equation approach (Chen et al. 2018). More specifically, we augment the Jones model (Jones 1991), the modified Jones model (Dechow et al. 1995), the Jones model augmented with return on assets (ROA), and the modified Jones model augmented with ROA (Kothari et al. 2005) with uncertainty measures. Similarly, the empirical analysis regarding real earnings management uses Roychowdhury’s (2006) models augmented with uncertainty measures. We add further controls for derivatives use and realized past volatility, measured by the oil and iron commodity price volatility (Joëts et al. 2017), to ensure that we properly control for current economic conditions. Prior research suggests that a volatile current state of the economy might have more influence on managerial decision-making than future uncertainty (Berger et al. 2020).

The results show that oil and iron firms decrease income using accrual earnings management in more uncertain periods. Further results show that oil and iron firms also manage production costs and discretionary expenses to decrease reported earnings as uncertainty about the future grows. The results show that the effect of uncertainty on earnings management is economically significant. The income-decreasing earnings management shifts earnings from uncertain times to more certain ones through cookie-jar reserving. The findings also demonstrate that different types of uncertainty have varying impacts on earnings management. Among these, we observe that climate policy uncertainty is more relevant than economic policy uncertainty and geopolitical uncertainty for real operations manipulation in oil firms. The opposite appears to be true for accrual earnings management in oil firms. Further investigation provides evidence related to the time dimension of uncertainty, as oil firms are more sensitive to near-term uncertainty (i.e. the next quarter). In contrast, iron firms are more responsive to uncertainty over longer periods (quarters t + 2 and t + 3).

This study also provides evidence that, as uncertainty increases, oil and iron firms that are more engaged in earnings management have more informative earnings. This suggests that earnings management under uncertainty aims to convey useful information on the firm’s rather than for garbling purposes.

This study contributes to recent research on macroeconomic uncertainty and earnings management in several ways (El Ghoul et al. 2021; Bermpei et al. 2022; Chauhan and Jaiswall 2023). First, consistent with predictions from Kirschenheiter and Melumad (2002) theoretical model of financial reporting, we show that commodity firms use income-decreasing accruals and real activities management in quarterly financial reporting. Future uncertainty has a significant negative impact on commodity firms through the channel of commodity prices, due to their business model (Damodaran 2009). Hence, rather than over-reporting, commodity firms prefer shifting earnings from uncertain to more certain times. In this way, they also exploit the stronger market reaction to higher earnings in less uncertain periods and maximize equity value by navigating prospective volatility.

Second, we provide fine-grained evidence that specific types of uncertainty have varying effects on earnings management. Climate policy uncertainty has a stronger impact on real earning management in oil firms than other types of uncertainty. Conversely, economic policy and geopolitical uncertainty impact more on real activities management by iron firms. These differences may be explained by factors like the industry’s vulnerability to policy changes, the business model, and the nature and implications of the uncertainty. While uncertainty related to environmental regulation is a primary concern for oil firms, uncertainty about international trade and trade tariffs is critical for iron firms' earnings management decisions. The industry traits and the business model can also account for different responses to uncertainty with different time dimensions. Specifically, differences in the operating cycles of oil and iron firms can explain their sensitivities to different timeframes of uncertainty.

This study recommends more in-depth research on uncertainty and earnings management, considering the firms’ specific business models and splitting uncertainty by the expected firm-level outcome. Our findings also suggest that uncertainty is an important factor explaining the pervasiveness of earnings management, thus complementing the research of Bertomeu et al. (2021).

This study also contributes to prior literature on earnings management in other ways. It provides evidence that commodity firms use earnings management to make earnings more informative for analysts and investors, rather than opportunistically conceal the firm’s performance. Signalling is awarded by investors with a lower cost of equity and price premiums (Francis et al. 2004), which are both highly desirable for managers operating under uncertainty. Our findings suggest that earnings management in mandatory financial reports is used to mitigate the adverse consequences of macroeconomic uncertainty on corporate valuation by investors. In this sense, this study: (a) contributes to existing studies on managers’ assessment of the costs and benefits of earnings management, with evidence of such assessment taking place under macroeconomic uncertainty (Baik et al. 2020); and (b) complements prior research on the use of voluntary disclosure to mitigate the adverse consequences of uncertainty on corporate valuation by investors with evidence on mandatory reporting (Boone et al. 2020; Nagar et al. 2019).

This study has practical implications for policymakers, auditors, investors, and other market participants. It informs market participants about commodity firms’ financial reporting quality, while also informing practitioners about the potential wider real effects on the economy and social well-being (for example, consumer goods availability and prices) of real earnings management by commodity firms.

The remainder of the study is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the literature. Section 3 develops the hypothesis. Section 4 describes the sample and research design. Section 5 displays the main findings, and Sect. 6 includes an investigation of the time dimension of uncertainty. Section 7 includes robustness and endogeneity tests. Section 8 investigates the informativeness of earnings. Section 9 discusses the findings, and Sect. 10 presents the conclusions.

2 Literature review

Prior research investigates the influence of the macroeconomic environment on accounting decisions, especially on earnings management. Kousenidis et al. (2013) document a decrease in earnings management during the European Sovereign Debt Crisis. Filip and Raffournier (2014) and Arthur et al. (2015) find that accrual quality improved during the Great Financial Crisis in a sample of European companies. Other studies on the Asian financial crisis provide competing results, including evidence of income-increasing accrual earnings management during the 1997–1998 Asian crisis (Ahmad-Zaluki et al. 2011; Chia et al. 2007). Lin and Wu (2022) focus on Chinese companies and investigate their reactions to oil price shocks and oil-implied volatility (OVX). This research produces mixed results, with the authors finding that “oil aggregate demand shocks decrease the degree of accrual earnings management, thus improving the quality of accounting. Surprisingly, OVX weakens that” (Lin and Wu 2022, p. 9). Kjærland et al. (2021) find that oil firms use income-decreasing accruals during an oil price shock to take big baths. The above-mentioned studies share a focus on specific periods of crisis. However, the macroeconomic environment produces fluctuations on a more frequent basis and displays significant volatility, beyond specific periods of expansion and recession (Bekaert et al. 2013).

Another stream of research focuses on economic policy uncertainty and earnings management, using the economic policy uncertainty (EPU) index from Baker et al. (2016), and obtains mixed evidence. Bermpei et al. (2022) find that firms use income-increasing discretionary accruals in periods of high economic policy uncertainty. By contrast, Chauhan and Jaiswall (2023) investigate a sample of Indian companies and find evidence that firms use income-decreasing discretionary accruals in periods of high economic policy uncertainty. Yung and Root (2019) use the absolute value of discretionary accruals and find evidence that firms increase earnings management in periods of heightened economic uncertainty. In this case, the authors do not explore whether earnings management is aimed at increasing or decreasing the current profits in periods of uncertainty. The study by El Ghoul et al. (2021) finds evidence of reduced earnings management during periods of high policy uncertainty, in which investors scrutinize firm-specific information more closely, thereby limiting managerial discretion.

Kirschenheiter and Melumad (2002) theoretical model of financial reporting may explain the above-mentioned mixed evidence. Kirschenheiter and Melumad (2002) states that “both taking a big bath and smoothing earnings can be part of a single equilibrium disclosure strategy” (p. 764). For sufficiently “bad” news periods (e.g., high uncertainty or negative prospects), managers under-report current earnings to report higher future earnings. If the news is not sufficiently “bad”, managers may boost reported income to safeguard rewards, reversing the over-reporting in good times, to take advantage of the impact of information decay (Kirschenheiter and Melumad 2002, p. 764). Ultimately, the manager’s private information, combined with that on external economic and market conditions, determine the financial reporting strategy, i.e. whether managers use income-increasing(or decreasing) earnings management in bad times to maximize equity value and/or for job contracting motives (Dechow et al. 2010). The above-mentioned mixed evidence on earnings management under uncertainty is based on different samples investigated in different periods, so scholars likely observed varying managerial assessments of the external economic and market conditions.

Consistently with Kirschenheiter and Melumad (2002) theoretical model, economic and finance literature suggests that exposure to uncertainty significantly varies across industries, with this aspect deserving specific focus beyond simple industry controls (see, for example, Miller 1993; Boutchkova et al. 2012; Byun and Jo 2018).

In a departure from previous studies, we focus on commodity firms and investigate a comprehensive measure of macroeconomic uncertainty and three types of uncertainty (Baker et al. 2016; Caldara and Iacoviello 2022; Gavriilidis 2021): economic policy, geopolitical, and climate uncertainty. To better understand the purpose of earnings management under uncertainty, we also investigate whether earnings management during periods of uncertainty increases or decreases earnings informativeness for external users of financial reports (Tucker and Zarowin 2006).

3 Hypothesis development

Prior research suggests that macroeconomic uncertainty motivates commodity firms to manage earnings downward. Chauhan and Jaiswall (2023) find that managers use income-decreasing discretionary accruals during uncertain periods to create cookie-jar reserves, which could be released during more certain periods (Chauhan and Jaiswell 2023). Stein and Wang (2016) report more negative discretionary accruals when financial markets are more volatile. Other studies suggest that commodity firm managers use income-increasing earnings management in periods of uncertainty. Uncertainty reduces revenues and generates additional adjustment costs related to labor and capital, which may reduce the firms’ market value (Hirshleifer et al. 2009; Ahmad-Zaluki et al. 2011; Binz 2022). Managers may use income-increasing earnings management because they believe the market undervalues firms in volatile periods, and they want to signal the firm’s future prospects beyond the contingent period of uncertainty. Bermpei et al. (2022) find evidence of income-increasing earnings management used to limit financial market participants’ concerns about the firm’s future prospects.

Based on Kirschenheiter and Melumad (2002) theoretical model, we expect commodity firms to engage in income-decreasing earnings management in more uncertain periods. Commodity firms are price-takers, and the volatility of revenues can be traced back to where the price level is (Damodaran 2009). These firms present large, fixed costs (such as depreciation, employees, and manutention). Hence, changes in commodity prices directly map onto revenues, cash flows, and earnings. Economic and market conditions likely make under-reporting preferable to over-reporting in commodity firms. Shareholders and investors tolerate bad performance during uncertain times and prefer more persistent earnings in less uncertain times, valuing them at a premium (Stein and Wang 2016). By contrast, over-reporting could draw investors’ scrutiny on unexpected earnings (El Ghoul et al. 2021). Given the nature and the extent of the macroeconomic uncertainty impact on such firms (exerted through the channel of commodity prices), we hypothesize that commodity firm managers under-report current earnings to report higher future earnings (Kirschenheiter and Melumad 2002). We formulate and test the following hypothesis:

HP1

Macroeconomic uncertainty triggers income-decreasing earnings management by commodity firms.

Prior literature suggests that different types of uncertainty affect earnings management differently. Some studies suggest that geopolitical uncertainty, related to, for example, wars or social uprisings, triggers earnings management in the commodity industry (Han and Wang 1998; Hsiao et al. 2016). Other studies suggest that natural disasters also trigger earnings management in the oil industry (Byard et al. 2007). Research on geopolitical or climate uncertainty uses shocks in its analysis and does not use continuous measures proposed by recent literature (Caldara and Iacoviello 2022; Gavriilidis 2021). Caldara and Iacoviello (2022) explain that geopolitical uncertainty and economic policy uncertainty are usually related to specific events, such as wars, election campaigns, and the issuance of trade tariffs. Besides climate shocks, climate uncertainty has a profound effect on the economy and society, which is distributed over time and triggers long-term adaptation of enhanced technologies and modes of production (Gavriilidis 2021). Furthermore, climate policy regulation is characterized by instances of progress and setbacks (Basaglia et al. 2022). The differences may be related to the management’s strategies to handle uncertainty, business model and industry susceptibility to policy changes, nature and implications of the uncertainty. For instance, government policy changes related to environmental regulations, taxation, or energy subsidies can significantly impact the oil industry. In such cases, firms may resort to real earnings management to handle uncertainty related to climate policy changes.

We formulate the following hypothesis:

HP2

Economic policy uncertainty, geopolitical uncertainty, and climate uncertainty have different impacts on earnings management in commodity firms.

Managers can use earnings management in response to macroeconomic uncertainty to garble reported earnings or to improve the informativeness of current earnings about the firm’s future performance (Tucker and Zarowin 2006). On the one hand, macroeconomic uncertainty could push managers to use earnings management for signalling purposes (Baik et al. 2020). Commodity firms’ managers may use earnings management to make earnings more useful for investors and analysts, communicating the firm’s “sustainable and repeatable” performance beyond the current volatility (Dichev et al. 2013, p. 1). On the other hand, commodity firm managers might garble their performance in uncertain times for job security or remuneration reasons (Graham et al. 2005; Baik et al. 2020). In any case, earnings management is unlikely to have a null effect on earnings informativeness, given investors’ attention to the firms’ fundamentals in uncertain periods (El Ghoul et al. 2021; Garel and Petit-Romec 2021). We formulate and test the following hypothesis:

HP3

Earnings management in response to macroeconomic uncertainty affects stock and earnings informativeness.

4 Research methodology

4.1 Sample selection

This study uses quarterly data from the Compustat North America database of oil and iron commodity firms.Footnote 2 Quarterly data are suitable for our study on earnings management in commodity firms (Han and Wang 1998; Hsiao et al. 2016). Diebold and Yilmaz (2008) find that macroeconomic uncertainty maps onto asset returns on a quarterly basis. Hence, managers are likely to manage earnings on a quarterly basis, without focusing only on the fourth and final quarter (Han and Wang 1998; Hsiao et al. 2016). Earnings management concentrated at the end of the year in annual reports could also be deemed risky for these firms and more easily detected by financial reports users. Finally, the US ASC 270 applies the integral method to interim reporting. Unlike the discrete method required by the IAS34, the ASC 270 allows more room for earnings management, as certain costs can be “allocated to interim periods based on estimates of time expired, benefits received, or other activity associated with the interim period” (Bogle 2020, p. 1).

We downloaded the quarterly data available from the first quarter of 1990 to the last quarter of 2019 of firms included in SIC code 13 (oil and gas extraction), SIC code 29 (petroleum refining), and NAICS 212210 (iron ore). We consider at least two widely used commodities to ensure robust findings. The study sample consists of 92,125 firm-year observations. A total of 56,458 firm-year observations represent SIC code 13 (oil and gas extraction) and SIC code 29 (petroleum refining), 6,820 firm-year observations represent SIC 29 (petroleum refining and related industries), and 2,636 firm-year observations represent NAICS 212210 (iron ore). The number of individual firms in each category is 1720 oil producers and 38 iron producers.

4.2 Measures of macroeconomic uncertainty

Following prior literature, we distinguish between realized volatility and uncertainty related to the future (Berger et al. 2020). Accurately distinguishing between realized volatility and uncertainty about the future is essential to reveal the genuine effect of uncertainty on managerial decision-making (Basu and Bundick 2017; Bloom et al. 2018).

We measure realized volatility using quarterly price commodity volatility (Blanchard and Riggi 2013; Feng et al. 2017; Joëts et al. 2017). Commodity price volatility is calculated as the standard deviation of the commodity (oil/iron) daily price in quarter t. In robustness checks, we also use commodity price volatility calculated as the standard deviation of the commodity (oil/iron) daily price in quarter t and t − 1 (that is, in the past 6 months). Our sources for the time series on commodity prices are the International Monetary Fund (IMF) commodity prices database and Refinitiv-Datastream.

We use the spread between the commodity quarterly spot price and the future price (basis risk) as a measure of uncertainty about the future. The concept of basis risk aligns with the concept of macroeconomic uncertainty in financial markets, where prospective volatility affects decision-making processes. Prior literature provides evidence that “the spread between commodity spot and futures prices (the basis) reflects the macroeconomic risks common to all asset markets” (Bailey and Chan 1993, p. 1; see also Watugala 2019; Bakas and Triantafyllou 2019).

The spread between the commodity spot price and the future price is also called basis risk, and is used in commodity studies and in finance studies on hedging (Alquist and Kilian 2010; Broll et al. 2015; Newell and Prest 2017). The spread between the current spot price and the future price can be either narrow or wide. The spread is narrow when the spot price converges toward the future price. When the spread is wide, uncertainty exists in the market. For example, if the spot price is much higher than the future price, there may be a risk of falling demand or shocks in the demand for the commodity. Suppose the future price is much higher than the current price. In that case, a significant risk premium is embedded in the future value, which can be related to several factors, including dwindling supply or shocks, such as those generated by wars or civil unrest (Baumeister and Kilian 2016). In this study, we use the absolute value of the spread between the quarterly spot price and the quarterly future price to measure the expected uncertainty.

As an alternative measure of uncertainty, we use the VIX index from the Chicago Board Options Exchange, which is also used to further investigate the time dimension of uncertainty.

We use the NYMEX future contracts for the oil industry available on the EIA website. Four types of contracts are included. Contract Type 1 is the price for deliveries in the next month. Types 2, 3, and 4 represent the prices for the following months. We present the results on Type 3 because it provides expectations about the next quarter’s price. We use the other contracts to perform robustness check analysis. The price of NYMEX futures contracts is used by central banks and the IMF to measure the market’s expectations for future prices and has been proven to be more accurate than econometric models (Alquist et al. 2013). We use the NYMEX future contracts for iron ore 62% swap for the iron industry available on Datastream. We selected it because it has the largest time span, with data starting from Q4 2010.

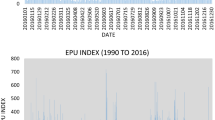

We also use specific indexes capturing different dimensions of uncertainty. The economic policy uncertainty index uses publicly available data from Baker et al. (2016), the geopolitical risk index uses publicly available data from Caldara and Iacoviello (2022), and the climate policy uncertainty index uses publicly available data from Gavriilidis (2021).Footnote 3 For each index, we calculate the quarterly average.

Table 1, Panel A summarizes the variables measuring realized volatility and uncertainty measures and their sources.

4.3 Research design

The main analysis tests the hypotheses using a set of accrual and real earnings management models augmented with commodity price volatility and commodity basis risk with a single equation research design (Chen et al. 2018). Earnings management studies usually calculate discretionary accruals in a first regression and then regress the discretionary accruals on the explanatory variables in a second regression. This two-step research design may suffer from potential bias caused by the misspecification of the first equation used to calculate the residuals. In particular, the regressors of the first equation in most studies are likely to be affected by the explanatory variable (Chen et al. 2018). This is the case of macroeconomic uncertainty, which likely affects regressors such as the sales and the PPE used to calculate discretionary accruals (or abnormal real activities). Using a single equation approach, we include the relevant explanatory variable (namely, macroeconomic uncertainty) directly in the earnings management model.Footnote 4 Our dependent variables are the total accruals, the production costs and the discretionary expenses (and not the relative estimated discretionary or abnormal components). By using well-established methods, we also reduce the subjectivity in the selection of the variables (McNichols and Stubben 2018).

We add a control for realized volatility, as mentioned in Sect. 4.2 above. We also add a control for the use of derivatives (Pincus and Rajgopal 2002). Prior literature produced mixed results on the effectiveness of hedging in creating value by reducing earnings volatility. Guay and Kothari (2003) find that in non-financial corporations (including mining and oil), the economic significance of hedging is low. Regarding the oil industry, Pincus and Rajgopal (2002) find that that commodity-price hedging positions are independent of decisions on earnings management. Another finding of the authors is that accruals management only takes the effect in the fourth quarter. Due to the nature of contracts, hedging may be less effective in managing uncertainty at a quarterly level. For this reason, Jin and Jorion (2006) claim that hedging does not affect market value in the oil industry. In any case, we run our analyses adding a control for derivative use with a measure by Barton (2001) The measure is calculated as the fair value of derivatives (items deracq and deraltq from the financial statements in Compustat) scaled by total assets.Footnote 5

Our macroeconomic uncertainty measure is firm-invariant in every quarter-year, incorporating quarter-by-year fixed effects. We add to our model’s firm fixed effects, which can capture the firm quarter-invariant features affecting earnings management, such as the internal control system, corporate culture or reputation, and managerial financial skills (Gormley and Matsa 2014).

To test our hypothesis, we estimate the following models:

1. Jones model (Jones 1991)

2. Modified Jones model (Dechow et al. 1995)

3. Jones model augmented with ROA (Kothari et al. 2005)

4. Modified Jones model augmented with ROA (Kothari et al. 2005)

Table 1 summarizes all the variables used in the empirical analysis and provides the sources. To ensure results are not driven by outliers, all the variables are winsorized at 1%.

Our attention is focused on the coefficient of \(Uncertainty_{t}\). A negative significant coefficient would signal that uncertainty triggers income-decreasing earnings management, aimed at generating cookie-jar reserves in more uncertain quarters (Chauhan and Jaiswell 2023). A positive significant coefficient would signal that uncertainty triggers income-increasing earnings management (Bermpei et al. 2022). A non-significant coefficient would signal that uncertainty does not affect earnings management.

This research also augments real activities management models (Roychowdhury 2006) with uncertainty measures. If uncertainty triggers earnings management, commodity firms may resort to underproduction and use discretionary expenses to decrease earnings in quarters with higher volatility (Roychowdhury 2006).Footnote 6 We estimate the following models.

5. Production costs:

6. Discretionary expenses:

The sample consists of unbalanced panel data. Thus, a violation could exist in the assumptions of the ordinary least square (OLS) estimation because of the error terms (Baltagi and Wu 1999). The model could have heteroscedasticity and serial correlation in the error term. To control for heteroscedasticity and serial correlated error, the empirical analysis uses the feasible general least squared (FGLS) estimation (Hansen 2007b; Romano and Wolf 2017), which is an unbiased estimation procedure (Hansen 2007a).

4.4 Descriptive statistics and univariate analysis

Table 2 displays the descriptive statistics of the commodity prices. Over the period 1990 Q1 to 2019 Q4, the oil quarterly average price was $74.68 per barrel, with the median being $73.06. The price is negatively skewed with a high level of kurtosis (1.41), suggesting a deviation from normality. Similar values can be observed for the future. Regarding the commodity price volatility, we note that the quarterly average standard deviation is approximately 4% of the average oil price and 7% of the average iron price.

Table 3 provides the descriptive statistics of the other variables used in the research. Table 4 displays the univariate analysis performed by computing the correlation matrix. It shows that all the quarterly average prices (West Texas Intermediate WTI, Iron) have a significant negative correlation with total accruals, with a p value < 0.05. Although at this stage no categorization is shown based on SIC codes, these results suggest potential accrual earnings management manipulations, as companies should display higher accruals as the commodity price increases. Commodity firms use accruals to reduce reported profits when the prices are high, in order to increase earnings in periods when the price decreases. Overall, oil and iron are highly positively correlated, suggesting that their prices show a similar pattern, and are a suitable proxy for macroeconomic trends in commodity producers. This ensures that any differences in the results are not driven by different behaviors of the commodity price.

5 Results

5.1 Accrual earnings management

Table 5 reports the results obtained by regressing equations 1–4. Across models, the oil and iron basis risk (Table 5, columns 1–8) is significantly and negatively correlated with total accruals, with p value < 0.01, after controlling for realized oil and iron quarterly price volatility. The control variables related to sales and adjusted sales show a significant (p value < 0.01) positive coefficient in the expected direction. Oil and iron firms use income-decreasing earnings management as uncertainty about the future increases. This finding suggests that the managers make cookie-jar reserves in uncertain periods and shift profits to more certain periods. This evidence provides support for HP1.

The effect of earnings management is not only statistically significant, but also economically relevant. For example, the coefficient estimated with the Jones model (Table 5, column 1) indicates that for every 1% increase in the basis risk (worth on average 2.78 cents), the net effect on total accruals is a decrease of 0.107% (Wooldridge 2010), which equates to approximately $400 thousands in each quarter (the average total accruals in the oil companies in our sample are approximately $371 million). A 1$ increase in the basis risk would result in an income-decreasing earnings management worth about 13.2 million $. The effect is economically significant considering that average quarterly earnings in the oil industry are $71.32 million. For iron firms, the results show that for every 1% increase in iron basis risk, the total accruals decrease by − 0.243%. A 1% increase in the quarterly iron basis risk (worth 6.84 cents) implies a decrease in the quarterly total accruals equivalent to about $612 thousands (the average quarterly total accruals in iron companies are approximately $252 million.) The effect is economically significant considering the average quarterly earnings in the iron industry are $60.70 million.

Table 6 presents the results obtained by regressing the accrual earnings management models augmented with the different types of uncertainty. Columns 1–3 display the results for oil companies, while columns 4–6 focus on iron companies. The dependent variable is total accruals, and the variables of interest are EPU (columns 1 and 4), geopolitical uncertainty (columns 2 and 5), and climate uncertainty (columns 3 and 6). The estimation incorporates the same controls included in Table 5. For brevity, we show the relevant control for realized volatility, measured by the commodity price volatility.

All the types of uncertainty show a negative and statistically significant coefficient (p value < 0.01), indicating that oil and iron companies engage in income-decreasing earnings management in periods of economic policy, geopolitical, and climate policy uncertainty. However, the impact is different across types of uncertainty and commodity firms. The coefficients suggest that EPU has the most significant impact, followed by geopolitical uncertainty and climate uncertainty, in oil firms. For iron firms, climate policy uncertainty triggers more income-decreasing accrual earnings management than geopolitical and economic policy uncertainty. These findings support HP2, showing that the impact is different across types of uncertainty. We further discuss these findings in Sect. 9.

5.2 Real activities management

Table 7 shows the empirical results related to real earnings management models. Columns 1 and 3 of Table 7 show that the basis risk has a negative association with production costs significant at the 1% level in oil and at 10% level in iron firms. Given that a 1% increase in basis risk (worth a few cents) corresponds to a decrease of approximately $161 thousands in production costs for oil firms and $870 thousands for iron firms in each quarter, the effect can be said to be economically significant. These findings suggest that oil and iron firms slow production in quarters with high basis risk to retain more indirect costs in the costs of goods sold and lower their reported earnings. Columns 2 and 4 of Table 7 indicate evidence of discretionary expenses used to decrease earnings. The findings provide further support for our hypothesis that macroeconomic uncertainty triggers income-decreasing earnings management (HP1).

Table 8 shows the empirical results related to real earnings management models augmented with the different types of uncertainty. Table 8, panel A displays the results related to oil firms, while panel B shows those related to iron firms. In Table 8, panel A, columns 1, 2, and 3, all three uncertainty types exhibit a negative and statistically significant association with production costs for oil and iron companies. In columns 4, 5, and 6, all three uncertainty types have a positive and stastically significant association with discretionary expenses for both oil and iron companies. These findings suggest that types of uncertainty have different impacts on earnings management using real operations. Table 8, panel B displays consistent results for iron firms. These findings support HP2 and are further discussed in Sect. 9.

6 Further investigation: time dimension of uncertainty

Uncertainty can impact the companies differently depending on the time horizon it will materialize. Multiple factors contribute to the unpredictability and lack of a complete information environment about future economic conditions.

In this section, we investigate the time dimension of uncertainty using the VIX, a measure of implied volatility of S&P 500 index options.Footnote 7 The VIX is used by prior literature as measure of uncertainty about the future (Berger et al. 2020). To investigate the time dimension of uncertainty, we use the base VIX which represents the expected volatility in the next 30 days; the VIX3M, which is the expected volatility in the next 90 days; and the VIX6M, which is the expected volatility in the next 180 days.

We download data from the CBOE database. We computer for each VIX the average value in the quarter and the standard deviation in the quarter. The tabulated results display coefficients obtained with the average values, but we obtain consistent esimation using the standard deviation.

Table 9 presents the results obtained by regressing the accrual earnings management models augmented with the different types of VIX. Table 9, columns 1–3 display the results for oil companies, while columns 4–6 those on iron companies. The dependent variable is total accruals, and the variables of interest are VIX (columns 1 and 4), VIX3M (columns 2 and 5), and VIX6M (columns 3 and 6). The same controls of Table 5 are used, but fro brevity reason we display only the relevant control for realized past volatility.

All the types of uncertainty show a negative and statistically significant coefficient (p value < 0.01), indicating that oil and iron companies engage in income-decreasing earnings management in periods with larger implied volatility. The findings suggest that oil companies put greater focus on closer in time uncertainty, since the coefficient of VIX (Table 9, column 1) is the highest. Iron firms appear to be more concerned with longer in time uncertainty, as the coefficient is higher for VIX6M than for VIX and VIX3M.

Table 10 shows the empirical results related to real earnings management models, panel A displays the results related to oil firms, while panel B shows those related to iron firms. Results are consistent with Table 7 and show a negative and statistically significant association between the VIX indexes and production costs for both oil and iron companies (Table 10, columns 1–3 of Panel A and Panel B). Furthermore, all three VIX have a positive and stastically significant association with discretionary expenses for both oil and iron companies (Table 10, columns 4–6 of Panel A and Panel B).

Table 10, panel A shows that VIX3M has the biggest impact on production costs of oil firms (column 2) and the VIX6M has the biggest impact on discretionary expenses. For real earnings management, uncertainty is assessed on a longer time horizon than for accrual earnings management, likely because manipulating accruals requires less time than adjusting real operatons. Table 10, panel B, yields similar findings for iron firms. The VIX6M is the most relevant for production costs, and VIX3M and VIX6M are more relevant for discretionary expenses than the VIX.

Overall, the findings provide further evidence supporting HP1.

7 Robustness and endogeneity checks

We undertake robustness checks using alternative measures of earnings mangement.

First, we consider the restatements (data from Audit Analytics) and the Accounting and Auditing Enforcement Releases (AAERs) by the Security Exchange Commission (Dechow et al. 2011).Footnote 8 The AAERs regard financial misstatements identified by the SEC and provide a proxy for poor financial reporting quality (Dechow et al. 2011). We did not have access to more granular data on the reason of restatements. Yet, they may provide an indication of poor financial reporting quality, either related to weak internal controls on accounting or to intentional misstatements (Dechow et al. 2010). We regress restatements and AAERs on the uncertainty measures plus a set of controls, including size, measured by the natural logarithm of the sales; leverage, measured by the total liabilities on total assets; profitability, measured by a return-on-assets index; book-to-market ratio; and the derivative use measure previously described. Table 11 displays the results of the analysis on oil firms and provide findings consistent with those of the main analyses. Indeed, realized commodity price volatility and prospective uncertainty have positive significant associations with restatement and AAERs (Table 11, Columns 1 and 5). Uncertainty indexes related to economic policy, climate uncertainty and geopolitical risks also have positive significant associations with restatement and AAERs (Table 11, Columns 2–4 and 6–8). Untabulated results on iron firms yields similar findings with less significant coefficients for restatements (p value < 0.10 for basis risk and p value < 0.05 for EPU). This may be due to the reduced number of restatements. We did not find AAERs for iron firms.

Further robustness checks use discretionary accruals and abnormal real operations as dependent variables (Vafeas and Vlittis 2023). To calculate discretionary accruals, we use the residuals from the Jones and the Modifies Jones models with Collins et al. (2017)’s specifications for quarterly data. The abnormal production costs and abnormal discretionary expenses are the residuals from Roychowdhury’s (2006) models. We then regress the discretionary accruals and abnormal real operations on the uncertainty measures plus a set of controls, including realized volatility; size; leverage; profitability; book-to-market ratio; and the derivative use. Table 12 shows the results of the analysis. Table 12, Column 1 and 2 of Panel A, and Columns 1 and 2 of Panel B, show that both oil and iron firms engage in income-decreasing accrual earnings management as uncertainty increases, after controlling for realized volatility. Also, Table 12, columns 5 and 6 of Panel A, show that oil firms use abnormal real operations to decrease income in more uncertain quarters. There is also evidence that iron firms use abnormal production costs to decrease income in more uncertain quarters (Table 12, Panel B, Column 5). These findings provide further support for HP1.

Another robustness check includes additional firm-level uncertainty measures from Arif et al. (2016), leverage and distress, to ensure that our empirical analysis captures the effect of macroeconomic uncertainty, after controlling for time-varying firm-level uncertainty (Hossain et al. 2023). Following Arif et al. (2016), leverage is calculated as total liabilities on total assets, and distress is a dummy set to one when Altman's Z-Score is less than 1.81. Untabulated results provide findings fully consistent with those of the main analyses (those displayed in Tables 5, 6, 7, 8), after including the above additional time-variant firm-level uncertainty controls.

We run endogeneity tests. The basis risk cannot be influenced nor fully anticipated by the average US commodity firm. Economic policy and other uncertainty indexes, as well as the VIX, are acknowledged as fully exogenous by prior literature, as the average firm can hardly influence economic policy, geopolitical risk, and climate uncertainty (See, for example, Baker et al. 2016; El Ghoul et al. 2021.) Some residual concerns may remain. For this reason, we run further tests using instrumental variables.

Our IV analysis performs a two-stage least squares (2SLS) estimation following Baker et al. (2023). In the paper, the authors use four different types of shocks (natural disasters, terrorist attacks, coups, and revolutions) to instrument the variables of interest: changes in the level and volatility of stock market returns. The variables for the four types of shocks are dummy variables taking the value of 0 when there is no shock and 1 when a shock occurs. So, if more shocks occur in the same period, the variable has the value 1. Furthermore, the variable is weighted by the increase in media coverage to ensure unanticipated events have greater importance. For example events such as elections are fully anticipated and does not show a spike in media coverage. Using the do file and the dataset provide by following Baker et al. (2023), we obtain shocks regarding the United States in the period 1990–2019 and use them to instrument our variable of interest. This ensures that the instruments are completely exogenous and we are instrumenting for both first and second moments jointly. It is noteworthy that our instruments are only natural disaster shocks and terrorist attacks because the United States did not experience coups or revolutions during our sample period. Thus, the two instruments (coups and revolutions) do not show variability and cannot be included because of collinearity.

Following Baker et al. (2023), which instruments uncertainty, we instrument both our measure of future uncertainty and our measure of realized volatility (past uncertainty). In the 2SLS first step, we regress the and the commodity basis risk and the price volatility on the four dummy variables representing shocks.

Equation 7—2SLS First stage

In the second step, we regress our main analysis equations 1–6 with the fitted price volatility (our measure for realized volatility) and the fitted basis risk (our measure of future uncertainty), as follows.

Untabulated results on the first stage regression shows a positive and statistically significant coefficients of the instruments when instrumenting for the basis risk. When instrumenting for the oil price volatility, the variable related to terrorist attack shows a negative and statistically significant result while the variable related to natural disaster has a positive and statistically significant coefficient.

Table 13 shows the second stage with results regarding accruals earnings management in oil firms. The variables of interest are the fitted basis risk and the fitted oil quarterly price volatility. The fitted basis risk shows a negative and significant coefficient (at the 0.01 level) in all four models while the oil price volatility does not show a statistical significant coefficient. The evidence supports the hypothesis that macroeconomic uncertainty is associated with income-decreasing earnings management in oil firms (HP1).

8 Earnings management and earnings informativeness

Prior studies suggest that managers use earnings management to either communicate their expectations regarding future profitability (Tucker and Zarowin 2006), or obfuscate the firm’s performance for opportunistic reasons (DeFond and Park 1997; Leuz et al. 2003). In this section, we investigate whether earnings management triggered by macroeconomic uncertainty is used by oil and iron firms to conceal the firm’s performance or increase their stock and earnings informativeness.

We first run an analysis (untabulated) using a well-established measure of earnings smoothing (Dou et al. 2013; Leuz et al. 2003), which is the correlation between the change in total accruals (TACC) and change in cash flows from operations (CFO), both scaled by lagged total assets over three consecutive quarters. We multiply the correlation by − 1 to ensure that larger values of the correlation mean more smoothing. We regressed this measure on our measure of macroeconomic uncertainty (basis risk) and other uncertainty indexes (EPU, geopolitical and climate uncertainty), adding a set of controls including the firms’ size, leverage, profitability, and book-to-market ratio. The findings confirm that macroeconomic uncertainty is associated with earnings smoothing for oil and iron firms.

Using the merged CRSP-Compustat quarterly database, we then investigate whether macroeconomic uncertainty affects stock price informativeness about the firm’s future performance. We modify Tucker and Zarowin (2006), adding interactions for macroeconomic uncertainty.Footnote 9 We estimate the following model:

where \(Return_{t}\) is the stock return in quarter t; \(EPS_{3t}\) is the sum of earnings per share in quarter t + 1 to t + 3; and \(ES_{t}\) is the earnings smoothing measure described above. Further, uncertainty is measured by the commodity price volatility (\(Uncertainty_{t} )\) and alternatively with a dummy indicating quarters with high volatility, namely, quarters with commodity price volatility above the median of the sample (\(HighUncertainty_{t} )\). The interaction term \(ES_{t} *EPS_{3t}\) is used by prior studies to ascertain whether earnings smoothing affects the ability of current stock returns to reflect information about future earnings (commonly called future earnings response coefficient FERC). If positive and significant, it implies that stock returns of firms with smoother earnings contain more information about future earnings than stock returns of firms with less smooth earnings (Dou et al. 2013). If negative and significant, it implies the opposite, with firms with smoother earnings having stock containing less information on future earnings. In this analysis, the coefficient of interest is that of the interaction \(ES_{t} * EPS_{3t} * Uncertainty_{t} \left( {or High Uncertainty} \right)\), namely, the interaction between the FERC and uncertainty. If positive and significant, it means that as uncertainty increases, firms with smoother earnings have stock returns containing more information on future earnings than the stock returns of firms with less smooth earnings. If this is the case, commodity firms use earnings smoothing to convey useful information to investors and analysts as a response to macroeconomic uncertainty. Conversely, commodity firms use earnings smoothing to conceal information about the firm’s performance.

Table 14 displays the results of the analysis. Table 14, column 1, shows that for oil firms, \(EPS_{3t}\) has a positive significant correlation with stock return (p value > 0.01), as expected. Uncertainty has a negative significant correlation with stock returns (p value < 0.01). The FERC (\(ES_{t} *EPS_{3t}\)) is not significant, but the FERC interacted with uncertainty is positive and significant at the 1% level. These findings provide evidence of the role of uncertainty in shaping the commodity firm’s earnings management decision. They suggest that as uncertainty increases, oil firms with smoother earnings have stock returns containing more information on future earnings than the stock returns of firms with less smooth earnings. These findings are confirmed in Table 14, column 2, when we use a dummy for the quarters in which uncertainty is high. Oil firms use smoothing to improve earnings informativeness within an uncertain macroeconomic environment and help investors and analysts predict future earnings amid volatile commodity prices.

Columns 3 and 4 of Table 14 display the analysis of iron firms, for which we have only 830 firm-year observations after merging Compustat and CRSP. Although with a weaker significance, the findings show that the FERC interacted with uncertainty has a positive and significant association with stock return with p value < 0.05 when using price volatility as measure of uncertainty, and with p value < 0.10 when using a dummy for quarters with high uncertainty.

We also examine whether smoothing improves earnings informativeness. If the smoothing strategy has the goal of improving the informativeness of earnings, smoothing should make the relation between current and future income stronger (Tucker and Zarowin 2006). We modify Tucker and Zarowin’s (2006) model for earnings informativeness as follows:

where \(EPS_{t}\) is the earnings per share in quarter t and the rest of the variables are as defined above. Again, the coefficient of interest is that of the interaction \(ES_{t} * EPS_{t} * Uncertainty_{t} \left( {or High Uncertainty} \right)\). A positive and significant coefficient indicates that, as uncertainty increases, smoothing strengthens the relation between current and future earnings, increasing the informativeness of the firm’s the current earnings for its future earnings. Conversely, as uncertainty increases, smoothing weakens this relation. Untabulated results show that the interaction is positive and significant at the 1% level for oil firms, using either \(Uncertainty_{t} \left( {or High Uncertainty} \right)\), while the coefficient is not significant for iron firms.

As a robustness check, we re-run our analysis using alternative measures of earnings smoothing, such as the correlation between the change in total accruals (TACC) and the change in cash flows from operations (CFO), over four, five, and six consecutive quarters. We also use another well-established measure of smoothing that implies the use of discretionary accruals (Baik et al. 2020; Tucker and Zarowin 2006), which is the Spearman correlation between the annual change in discretionary accruals (DAC) and pre-managed income (PMI): Corr(ΔDAC, ΔPMI). The untabulated results are consistent with those displayed in Table 14.

9 Discussion of the findings

This study provides evidence that commodity firms engage in income-decreasing earnings management in response to macroeconomic uncertainty. Kirschenheiter and Melumad (2002) theoretical model predict that whether firms under-report or over-report earnings during “bad” times depends on the managers’ assessment of the severity of external economic and market conditions, along with their perceptions of the uncertainty potential impact. We find that commodity firm managers under-report current earnings to report higher future earnings. Shifting earnings from uncertain to more certain times through cookie-jar reserving maximizes equity value of commodity firms navigating realized and prospective volatilty. Outside investors are likely to tolerate a bad performance during periods of uncertainty from commodity firms. Conversely, during more certain times, managers release earnings upward as markets more strongly react to the positive news and expect performance during such periods to be more persistent (Stein and Wang 2016).

This research provides evidence that managers also use real earnings management. Oil and iron firms slow production and add discretionary expenses in quarters with high uncertainty to decrease income. Anticipating discretionary expenses (such as maintainance) shifts costs from the future to current periods, saving future periods from such costs. Slowing production and inventory replenishment leaves a higher portion of overheads in the cost of goods sold, decreasing the current income. Real option theory suggests that slowing production is a valuable option in uncertain times for the future state of the business environment, in which demand may increase or decrease (Kellogg 2014). The observed earnings management is consistent with that observed for investments and uncertainty in the oil industry (Kellogg 2014).

This study also provides evidence that different types of uncertanty affect earnings management in different ways. Economic policy uncertainty and geopolitical uncertainty appears the two most relevant factors influencing accrual earnings management in oil firms, while climate policy uncertainty is more relevant for real earnings management in these firms. These differences may be associated with management strategies to cope with uncertainty, the business model, industry vulnerability to policy changes, and the nature and implications of the uncertainty. Economic policy uncertainty and geopolitical are often related to individual events and accrual earnings management provides an immediate response. Changes to environmental regulations, taxation, or energy subsidies may lead oil firms to manage real operating adjusting inventory, production levels and other operating expenses, to safeguard the firm’s value from policy changes (Erikson et al. 2018; Makarem et al. 2023). Likewise, for instance, uncertainty involving international trade regulation and trade tariffs—whether related to economic policy or geopolitical risks—is likely to prompt iron firms to manipulate real operations by adjusting inventory and production (Yang et al. 2022). Overall, our findings advocate further in-depth research on uncertainty and earnings management, categorizing uncertainty by the expected firm-level outcome.

Industry characteristics and business models can explain variations in the time effect of uncertainty on earnings management. Oil firms tend to be more sensitive to short-term uncertainty, whereas iron firms show a greater responsiveness for uncertainty over more extended periods (up to two quarters into the future). Oil firms operate within a shorter production and inventory cycle due to the nature of their production process. The distribution of oil and related products typically involve shorter-term processes. As a result, oil firms are more sensitive to immediate changes in market conditions, such as short-term fluctuations in the demand or geopolitical events impacting supply chains (Baumeister and Kilian 2016). On the other hand, mining and processing iron ore has longer production and inventory cycles (Adams et al. 2019). Consequently, iron firms are responsive to uncertainty spanning over longer timeframes, aligning with their extended operating cycle.

Uncertainty increases the information asymmetry between managers and outside investors (Ghosh and Olsen 2009; Stein and Wang 2016), also causing tightened investor scrutiny (El Ghoul et al. 2021; Garel and Petit-Romec 2021). Our results show that earnings management is not used to garble earnings. Rather, it is informative for investors and analysts, as it strengthens stock and earnings informativeness. Managers of commodity firms operating under uncertainty use earnings management for signaling rather than for garbling purposes. Indeed, signaling is rewarded by investors with lower cost of equity and price premiums (Baik et al. 2020; Francis et al. 2004), which are both highly desirable for managers operating under uncertainty. In this sense, this research offers evidence on the managerial assessment of the costs and benefits of earnings management under times of uncertainty (Baik et al. 2020).

The signaling by managers suggests that earnings management in mandatory financial reports is used to mitigate the adverse consequences of macroeconomic uncertainty on corporate valuation by investors and analysts. By managing earnings, commodity firms increase earnings informativeness beyond the current uncertainty and convey useful information for investors and analysts. Prior research has found that firms use voluntary disclosure to mitigate the adverse consequences of policy uncertainty on corporate valuation by investors (Boone et al. 2020; Nagar et al. 2019). We complement these findings with evidence on the use of mandatory financial reports.

This study has practical implications. Policymakers, auditors, investors, and other market participants are now informed that macroeconomic uncertainty affects the quality of financial reporting by commodity firms. The findings of this study contributes to the debate on accounting and disclosure regulation for extractive industries converging globally; an example of such a regulation is the IASB project on Extractive Activities (2022). This study also informs practitioners on the behavior of commodity firms, which play a central role in the current global economy and international political landscape (currently plagued by the Ukraine War and the energy crisis). Real operations used to smooth earnings, such as deliberate underproduction, have wider real effects on the economy and social well-being. Underproduction of oil and iron in periods of high volatility can cause significant economic and human costs, as this can trigger inflation and increase consumer goods prices. It can also reduce the availability of consumer products such as food (Braun and Tadesse 2012).

Future research might focus on countries where commodity firms are primarily state-owned enterprises and the national governments have a strong influence on financial reporting and real choices. This would serve to expand the literature on how different ownership models influence earnings management practices under uncertainty. Research on agricultural commodities to further advance knowledge in this area could also prove highly valuable.

10 Conclusions

This study provides evidence that macroeconomic uncertainty triggers income-decreasing earnings management in commodity firms. The findings show that oil and iron firms use both accruals and real operations to decrease earnings in quarters with high basis risk. The findings show that earnings management by commodity firms is economically significant. Further investigation shows that different types of uncertainty have varying effect on earnings management and provides evidence related to time dimension of the effect of uncertainty. Finally, the findings show that earnings management is aimed at providing useful information about firms’ economic performance to investors during uncertain periods.

This study contributes to the literature on macroeconomic uncertainty and earnings management (El Ghoul et al. 2021; Bermpei et al. 2022; Chauhan and Jaiswall 2023) with evidence of income-decreasing earnings management in uncertain times by commodity firms. It shows that the types of uncertainty have varying impact on earnings management. The study also contributes to prior earnings management literature by showing that macroeconomic uncertainty motivates earnings management aimed at signaling purposes, i.e. at mitigating the adverse consequences of uncertainty on corporate valuation by market participants.

The research has practical implications for policymakers, auditors, investors, and other market participants, contributing to the debate about accounting and disclosure regulation in the extractive industries (IASB 2022). This study informs market participants and stakeholders about the earnings quality of commodity firms, as well as the potential real effects on the economy and social well-being (such as consumer goods availability and prices) of real earnings management by commodity firms.

This study acknowledges some limitations. Being focused on commodity firms, some of its results may not be generalizable to other industries (e.g. those on climate uncertainty and real earnings management). However, it is also true that, as mentioned above, macroeconomic uncertainty has industry-specific effects on commodities (Damodaran 2009), and industry-specific earnings management is likely to be in place for commodity firms (Han and Wang 1998; Dayanandan and Donker 2011; Hsiao et al. 2016).

Data availability statement

The financial data that support the findings of this study are available from Wharton Research Data Services. Restrictions apply to the availability of the data, which were used under license for this study. Data can be downloaded at https://wrds-web.wharton.upenn.edu/wrds/index.cfm under the permission of the data provider. Commodity price data are available at Datastream-Refinitiv and IMF Primary Commodity System Primary Commodity Price System—At a Glance—ANNUAL—IMF Data. Restrictions apply to the availability of the data from Datastream-Refinitiv, which were used under license for this study. Data from the IMF are available without restrictions and freely accessible.

Notes

Macroeconomic uncertainty received huge attention after Bloom’s (2009) seminal work. Prior literature provides multiple definitions of macroeconomic uncertainty, converging on the idea that uncertainty is difficulty in forecasting the future due to high environmental volatility (Ahir et al. 2022; Altig et al. 2020).

These resources are fundamental for the overall economic activity and provide key contributions to the GDP of 63 countries worldwide (World Bank 2021). Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/extractiveindustries/overview#1.

All the data are freely available for download at: https://policyuncertainty.com.

Chen et al. (2018) strongly suggest avoiding the two-step procedure: “We point out that there is no econometric justification for this two-step procedure and emphasize that the most straightforward way to avoid the bias generated by the procedure is to simply estimate the model in a single regression” (p. 752). They add, “The most basic solution is to simply estimate the coefficients for all the model regressors in a single-, as opposed to two-step regression” (p. 782).

A more refined measure would be the ratio between the derivative position and amount of risk exposure. This would require an extensive analysis of the footnotes, searching for the portion of production hedged, which is hardly feasible with large longitudinal samples (Jin and Jorion 2006). The derivative use measure is viable, as it is based on the fair value of the hedge, which represents the amount exposed to changes in the value of the derivative underlying (Barton 2001).

Underproduction keeps higher portions of indirect costs in the value of goods sold, thus lowering earnings. This behavior would be consistent with anecdotal and practitioners’ evidence that some undersupply exists in periods of high volatility (See the disagreement between the US government and the US oil firms over supplies in the aftermath of the pandemic and during the Ukraine War; CNN 2021).

We thank an anonymous reviewer for suggesting the analysis.

Dataset available from Dechow et al. (2011) website.

This approach is used in prior literature to investigate factors affecting the use of smoothing. For example, Baik et al. (2020) add interactions with managerial ability.

References

Adams RG, Gilbert CL, Stobart CG (2019) The mining cycle. In: Modern management in the global mining industry. Emerald Publishing Limited, pp 215–230

Ahir H, Bloom N, Furceri D (2022) The world uncertainty index. National Bureau of Economic Research (No, w. 29763)

Ahmad-Zaluki NA, Campbell K, Goodacre A (2011) Earnings management in Malaysian IPOs: the East Asian crisis, ownership control, and post-IPO performance. Int J Account 46:111–137

Alquist R, Kilian L (2010) What do we learn from the price of crude oil futures? J Appl Econ 25:539–573

Alquist R, Kilian L, Vigfusson RJ (2013) Forecasting the price of oil. In Handbook of economic forecasting, vol 2. Elsevier, pp 427–507

Altig D, Baker S, Barrero JM, Bloom N, Bunn P, Chen S, Davis SJ, Leather J, Meyer B, Mihaylov E, Mizen P, Parker N, Renault T, Smietanka P, Thwaites G (2020) Economic uncertainty before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Public Econ 191:104274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104274

Arif S, Marshall N, Yohn TL (2016) Understanding the relation between accruals and volatility: A real options-based investment approach. J Account Econ 62(1):65–86

Arthur N, Tang Q, Lin ZS (2015) Corporate accruals quality during the 2008–2010 global financial crisis. J Int Account Audit Tax 25:1–15

Baik B, Choi S, Farber DB (2020) Managerial ability and income smoothing. Account Rev 95:1–22

Bailey W, Chan KC (1993) Macroeconomic influences and the variability of the commodity futures basis. J Finance 48(2):555–573

Bakas D, Triantafyllou A (2019) Volatility forecasting in commodity markets using macro uncertainty. Energy Econ 81:79–94

Baker SR, Bloom N, Davis SJ (2016) Measuring economic policy uncertainty. Q J Econ 131:1593–1636

Baker SR, Bloom N, Terry SJ (2023) Using disasters to estimate the impact of uncertainty. Rev Econ Stud 90(5):1–41

Baltagi BH, Wu PX (1999) Unequally spaced panel data regressions with AR (1) disturbances. Econ Theor 15:814–823

Barton J (2001) Does the use of financial derivatives affect earnings management decisions? The Account Rev 76(1):1–26

Basaglia P, Carattini S, Dechezleprêtre A, Kruse T (2022) Climate policy uncertainty and firms’ and investors’ behavior. https://ethz.ch/content/dam/ethz/special-interest/mtec/cer-eth/resource-econ-dam/documents/research/sured/sured-2022/Climate%20policy%20uncertainty%20and%20firms’%20and%20investors’%20behavior.pdf. Accessed June 2023

Basu S, Bundick B (2017) Uncertainty shocks in a model of effective demand. Econometrica 85(3):937–958. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA13960

Baumeister C, Kilian L (2016) Forty years of oil price fluctuations: why the price of oil may still surprise us. J Econ Perspect 30:139–160

Bekaert G, Hoerova M, Lo Duca ML (2013) Risk, uncertainty and monetary policy. J Monet Econ 60:771–788

Berger D, Dew-Becker I, Giglio S (2020) Uncertainty shocks as second-moment news shocks. Rev Econ Stud 87(1):40–76

Bermpei T, Kalyvas AN, Neri L, Russo A (2022) Does economic policy uncertainty matter for financial reporting quality? Evidence from the United States. Rev Quant Finance Account 58(2):795–845

Bertomeu J, Cheynel E, Li EX, Liang Y (2021) How pervasive is earnings management? Evidence from a structural model. Manag Sci 67:5145–5162

Binz O (2022) Managerial response to macroeconomic uncertainty: Implications for firm profitability. Account Rev 97:89–117

Blanchard OJ, Riggi M (2013) Why are the 2000s so different from the 1970s? A structural interpretation of changes in the macroeconomic effects of oil prices. J Eur Econ Assoc 11:1032–1052

Bloom N (2009) The impact of uncertainty shocks. Econometrica 77:623–685

Bloom N, Floetotto M, Jaimovich N, Saporta-Eksten I, Terry SJ (2018) Really uncertain business cycles. Econometrica 86(3):1031–1065. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA10927

Bogle K (2020) Interim financial reporting: IFRS® Standards vs. US GAAP. https://advisory.kpmg.us/articles/2020/interim-financial-reporting.html

Boone AL, Kim A, White JT (2020) Local policy uncertainty and firm disclosure. Vanderbilt Owen Graduate School of Management research paper

Boutchkova M, Doshi H, Durnev A, Molchanov A (2012) Precarious politics and return volatility. Rev Financ Stud 25(4):1111–1154

Braun JV, Tadesse G (2012) Food security, commodity price volatility, and the poor. In: Institutions and comparative economic development. Springer, pp 298–312

Broll U, Welzel P, Wong KP (2015) Futures hedging with basis risk and expectation dependence. Int Rev Econ 62:213–221

Byard D, Hossain M, Mitra S (2007) US oil companies’ earnings management in response to hurricanes Katrina and Rita. J Account Public Policy 26(6):733–748

Byun SJ, Jo S (2018) Heterogeneity in the dynamic effects of uncertainty on investment. Can J Econ 51(1):127–155

Caldara D, Iacoviello M (2022) Measuring geopolitical risk. Am Econ Rev 112(4):1194–1225

Chauhan Y, Jaiswall M (2023) Economic policy uncertainty and incentive to smooth earnings. Int Rev Econ Finance 85:93–106

Chen WEI, Hribar P, Melessa S (2018) Incorrect inferences when using residuals as dependent variables. J Account Res 56:751–796

Chia YM, Lapsley I, Lee HW (2007) Choice of auditors and earnings management during the Asian financial crisis. Manag Audit J 22(2):17–196

CNN (2021) Biden asks FTC to “immediately” look into whether illegal conduct is pushing up gas prices. https://edition.cnn.com/2021/11/17/politics/biden-high-gas-prices-ftc-letter/index.html. Accessed 11 Jan 2022

Collins DW, Pungaliya RS, Vijh AM (2017) The effects of firm growth and model specification choices on tests of earnings management in quarterly settings. Account Rev 92(2):69–100

Damodaran A (2009) Ups and downs: valuing cyclical and commodity companies. Available at SSRN 1466041. SSRN Journal

Dayanandan A, Donker H (2011) Oil prices and accounting profits of oil and gas companies. Int Rev Financ Anal 20:252–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2011.05.004

Dechow PM, Sloan RG, Sweeney AP (1995) Detecting earnings management. Account Rev 70:193–225

Dechow P, Ge W, Schrand C (2010) Understanding earnings quality: a review of the proxies, their determinants and their consequences. J Account Econ 50:344–401

Dechow PM, Ge W, Larson CR, Sloan RG (2011) Predicting material accounting misstatements. Contemp Account Res 28:17–82

DeFond ML, Park CW (1997) Smoothing income in anticipation of future earnings. J Account Econ 23:115–139

Dichev ID, Graham JR, Harvey CR, Rajgopal S (2013) Earnings quality: evidence from the field. J Account Econ 56:1–33

Diebold FX, Yilmaz K (2008) Macroeconomic volatility and stock market volatility, worldwide. National Bureau of Economic Research (No, w. 14269)

Dou Y, Hope OK, Thomas WB (2013) Relationship-specificity, contract enforceability, and income smoothing. Account Rev 88:1629–1656

El Ghoul S, Guedhami O, Kim Y, Yoon HJ (2021) Policy uncertainty and accounting quality. Account Rev 96:233–260

Feng J, Wang Y, Yin L (2017) Oil volatility risk and stock market volatility predictability: evidence from G7 countries. Energy Econ 68:240–254

Filip A, Raffournier B (2014) Financial crisis and earnings management: the European evidence. Int J Accont 49:455–478

Francis J, LaFond R, Olsson PM, Schipper K (2004) Costs of equity and earnings attributes. Account Rev 79:967–1010

Garel A, Petit-Romec A (2021) Investor rewards to environmental responsibility: evidence from the COVID-19 crisis. J Corp Finance 68:101948

Gavriilidis K (2021) Measuring climate policy uncertainty. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3847388

Ghosh D, Olsen L (2009) Environmental uncertainty and managers’ use of discretionary accruals. Account Organ Soc 34(2):188–205

Gormley TA, Matsa DA (2014) Common errors: how to (and not to) control for unobserved heterogeneity. Rev Financ Stud 27(2):617–661

Graham JR, Harvey CR, Rajgopal S (2005) The economic implications of corporate financial reporting. J Account Econ 40:3–73

Gray SJ, Hellman N, Ivanova MN (2019) Extractive industries reporting: a review of accounting challenges and the research literature. Abacus 55:42–91

Guay W, Kothari SP (2003) How much do firms hedge with derivatives? J Financ Econ 70(3):423–461

Han JC, Wang SW (1998) Political costs and earnings management of oil companies during the 1990 Persian Gulf crisis. Account Rev 73:103–117

Hansen CB (2007a) Asymptotic properties of a robust variance matrix estimator for panel data when T is large. J Econ 141:597–620. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2006.10.009

Hansen CB (2007b) Generalized least squares inference in panel and multilevel models with serial correlation and fixed effects. J Econ 140:670–694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2006.07.011

Hirshleifer D, Hou K, Teoh S (2009) Accruals, cash flows, and aggregate stock returns. J Financ Econ 91:389–406