Abstract

Behavioral inhibition (BI) is a temperamental trait characterized by a consistent pattern of behavioral and emotional responses to unfamiliar people and novel situations. BI exhibits moderate stability across development and is considered a risk factor for the emergence of emotional disorders in adolescence and adulthood, making early assessment crucial for understanding this behavioral pattern. In the Portuguese context, there is a paucity of measures specifically designed to assess BI in childhood. To address this gap, we aimed to adapt and examine the psychometric properties of the Behavioral Inhibition Questionnaire (BIQ) in Portuguese children. We obtained BIQ ratings from both parents and teachers of 435 children (average age = 57.1 months; SD = 13.8). Confirmatory factor analysis supported a six-factor measurement model, each factor loading onto a higher-order BI factor. Additionally, we included a method factor to account for reversed items. Full scalar measurement invariance across gender and age groups was supported. Parents and teachers showed good agreement in their ratings of BIQ scores. Comparisons with other instruments revealed good convergent validity. The BIQ scores showed acceptable reliability, although the subscales exhibited limited sensitivity in discriminating between different contexts where BI may manifest. This study suggests that the BIQ is a reliable and valid tool for assessing BI in Portuguese children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Behavioral inhibition (BI) is a temperamental predisposition that manifests as heightened sensitivity to new stimuli and a tendency to avoid unfamiliar people, situations, and objects (Kagan et al., 1984). Approximately 15% of children exhibit BI, characterized by reduced approach, caution, and withdrawal in response to unfamiliarity (Kim et al., 2011). BI can be observed across various social and non-social contexts, including interactions with unfamiliar adults or peers, encounters with novel objects and participation in low-risk physical activities (Kochanska & Radke-Yarrow, 1992; Reznick et al., 1986).

BI is recognized as a significant risk factor for anxiety disorders, particularly social anxiety disorder, in later childhood and adolescence (Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2009; Clauss & Blackford, 2012). Additionally, BI seems to be involved in the manifestation of other psychological disorders, including selective mutism (Muris et al., 2015), autism spectrum disorders (Schiltz et al., 2018), schizophrenia (Feola et al., 2019), general substance abuse (Lahat et al., 2012), psychopathic-like personality (Glenn et al., 2007; Salekin, 2017), and depression in young adulthood (Caspi et al., 1996; Jaffee et al., 2002). Due to its transdiagnostic nature, it is crucial to develop and validate reliable remeasures for assessing BI (Feola et al., 2019).

While the relevance of BI manifestations during childhood is well-established, to our knowledge there are a limited number of report measures specifically tailored to assess BI in preschool years. This measures include the Preschool Behavioral Inhibition Scale (P-BIS; Ballespí et al., 2012), the Behavioral inhibition/Behavioral activation scales (BIS/BAS; Carver & White, 1994), the Temperament Assessment Battery for Children – Revised (TABC-R; Presley & Martin, 1994) and the Behavioral Inhibition Questionnaire (BIQ; Bishop et al., 2003). However, P-BIS and BIS/BAS scales focus solely on BI in social situations, while TABC includes only one subscale dedicated to BI. In our opinion, the BIQ stands out as the most comprehensive tool for assessing BI in preschool children, as it utilizes parent and teacher reports to capture BI across a diverse range of novelty contexts (Bishop et al., 2003). Drawing upon Kagan’s theory, the BIQ comprises 30 items (28 items for the teacher version) organized into six contexts reflecting three broad domains: social novelty (unfamiliar adults, unfamiliar peers, performance situations), situational novelty (separation/preschool, unfamiliar situations) and physical challenge.

The validation of the original Australian BIQ version (Bishop et al., 2003) was based on the reports of 613 mothers (M age = 34.55 years, SD = 4.59), 506 fathers (M age = 37.28 years, SD = 5.50) and 585 preschool teachers about their 619 children (3–5 years; M = 48.99 months, SD = 5.92). Confirmatory factor analysis corroborated six correlated factors (associated with the six contexts) which loaded onto a single higher-order construct (BI). The scale presented good reliability: Cronbach’s alpha was above 0.80 for all factor scores of the teacher and parents’ reports (except for the father’s report on the physical challenge domain; α = 0.72); test–retest reliability of parents’ reports was satisfactory, ranging from 0.55 to 0.78. The agreement between reports was also adequate, with strong positive correlations between mother’s and father’s total scores (r = 0.69) and with teacher’s total score (mother: r = 0.47; father: r = 0.43). In support of convergent validity, the BIQ total score was strongly associated with the TABC inhibition subscale (Presley & Martin, 1994) completed by parents and teachers (r ranged between 0.85 and 0.87); observational ratings, obtained while children interacted with an adult stranger, also correlated positively with the BIQ total score (r ranged between 0.25 and 0.46).

The BIQ has been translated and adapted for use in four additional languages: Dutch (Broeren & Muris, 2010), American English (Kim et al., 2011), Israeli/Hebrew (Mernick et al., 2018), and Italian (Agostini et al., 2021). There is also a Dutch abbreviated version of BIQ, comprising 14 items (Vreeke et al., 2012). Considering BIQ’s dimensionality, all these studies supported the original six-factor structure proposed by Bishop and collaborators (2003), although two of them did not test the existence of a second-order generic BI factor (Broeren & Muris, 2010; Mernick et al., 2018). All studies also confirmed good reliability for the BIQ total score (internal consistency: 0.92 ≤ Cronbach’s α ≤ 0.97), both in preschool samples (3–5 years; Agostini et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2011) and in older samples (4–15 years; Broeren & Muris, 2010; Mernick et al., 2018). All BIQ subscales also demonstrated good reliability (0.79 ≤ α ≤ 0.95), except for the Physical Challenge subscale, which consistently exhibited lower internal consistency (0.41 ≤ α ≤ 0.90). When test–retest data are available, results also support excellent time stability for BIQ total score (0.58 ≤ r ≤ 0.95) and subscales (0.42 ≤ r ≤ 0.93).

To date, BIQ has been applied in multiple research domains, including studies on anxiety onset risk (Bourdon et al., 2019; Dodd et al., 2020; Stumper et al., 2017; Suarez et al., 2019) and selective mutism (Muris et al., 2021). It has also been used to evaluate the effectiveness of early interventions for inhibited or anxious children (Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2021; Lau et al., 2017), validate observational measures (Faísca et al., 2021), and contributed to investigations on attentional bias to threat (Fu et al., 2019; Wise et al., 2021), brain regions associated with fear response (Auday & Pérez‐Edgar, 2019), and EEG measures of social anxiety in behaviorally inhibited children (Anaya et al., 2021; Poole et al., 2020).

Given the robust psychometric properties and recent applications in empirical studies, the BIQ is deemed a valuable measure for assessing children’s behavioral inhibition across various social and non-social contexts as reported by adults. However, there are still some unanswered questions regarding its measurement model. The original Australian validation study reported a second-order BI factor, but only two out of four subsequent versions of the BIQ confirmed this generic factor. The other two studies (Broeren & Muris, 2010; Mernick et al., 2018) did not provide any rationale for not testing its inclusion in BIQ’s measurement model. Additionally, the adjustment of the BIQ’s six-factor model has been suboptimal in some cases. For instance, in the original Australian study, the CFI for both mother’s and father’s models was below the desired level (0.88 and 0.86, respectively), as well as the RMSEA index (0.08 for both models); similar suboptimal fit indexes were reported for American Teachers (CFI = 0.87; RMSEA = 0.09), Israeli mothers (CFI = 0.83 and RMSEA = 0.09) and one of the Dutch age groups (CFI = 0.88; RMSEA = 0.08). This suboptimal fit suggests that the six-factor model might not be sufficient to capture the variance in the responses to BIQ. Each item of the questionnaire has a reversed version, one expressing an inhibited behavior (for instance, “Item 17. Is hesitant to explore new play equipment”) and the other describing disinhibition and greater social adjustment of the child (“Item 29. Happily explores new play equipment”). It is known that the presence of reverse items might affect response patterns (Suárez-Alvarez et al., 2018). While the inclusion of such items in a questionnaire aims to reduce acquiescence bias, they also make item interpretation difficult, causing confusion in the participant, activating a different response style, and even careless responding (van Sonderen et al., 2013). So, hypothesizing a method factor that encompasses all reversed items might account for the residual variance not explained by the BI six-factor model. Finally, the internal consistency of BIQ scores had been assessed almost exclusively through Cronbach’s alpha index (although Composite and Guttman’s split-half reliability were computed for the Italian version); but considering the BIQ hierarchical and multidimensional structure, model-based reliability analysis through omega coefficients seems to be more appropriate, since such coefficients represent the proportion of the variance of the scores due to each specific and generic factor (Brunner et al., 2012).

Our primary goal was to develop a European Portuguese version of the BIQ and assess its psychometric properties in a preschool sample using parent and teacher reports. We anticipate that this version would retain the established six-factor structure and incorporate a higher-order general BI factor, consistent with prior research. Furthermore, we plan to test a model including a method factor associated with reversed items. Additionally, we expect to observe robust reliability measures and positive correlations with established measures of behavior inhibition (e.g., TABC) and anxiety, encompassing social anxiety, generalized anxiety, and separation anxiety (e.g., Preschool Anxiety Scale – PAS). These measures have been used in prior studies that validated the BIQ (e.g., Broeren & Muris, 2010; Vreeke et al., 2013).

Method

Participants

Four hundred thirty-five children (217 girls, 49.9%), aged 3 to 6 years (M = 57.0 months, SD = 13.77), participated in the study. The study involved two versions of the BIQ: the Parent version, completed by 226 mothers, 37 fathers, and 172 by both parents (Mothers/Fathers), and the Teacher version, filled out by 54 preschool teachers.

Families with a preschool child aged between 3 and 6 years, who lived with at least one Portuguese-speaking biological parent, were eligible to participate. Children were recruited from 27 kindergartens and preschools in the Faro region (Portugal). Approximately 60% of the children had at least one sibling, occupying the first (37.4%) and second positions (50.4%,) birth order positions. Mothers had an average age of 36.2 years (SD = 5.17) and 14.9 years of schooling (SD = 3.77), while fathers were, on average, 38.6 years old (SD = 6.04) with 13.3 years of schooling (SD = 3.91).

Parents were invited to participate by providing them with an information letter and a consent form. Exclusion criteria included previous diagnosis of a major psychological or medical condition for both children and parents. Approximately 33% of the parents (443 out of the 1360 invited parents) responded positively and completed the questionnaires. Over 90% of the progenitors were Portuguese and none were excluded due to significant medical conditions or developmental disabilities. Eight parents were excluded due to incomplete questionnaire data.

After obtaining parental consent, teachers were asked to fill in the BIQ for each child. Fifty-four female teachers with an average age of 38.7 years (SD = 9.64) provided information about 314 children (return rate of 72.2%). To check for selection bias, children with and without teacher reports were compared based on BIQ parents’ reports and did not differ in the total score or any of the six subscales.

To assess BIQ temporal stability, parents were contacted again to complete the questionnaire one month later. A total of forty-three participants (88.4% mothers: M = 37.6 years, SD = 3.94; 11.6% fathers: M = 39.5 years, SD = 5.44; Children: M = 67.1 months, SD = 18.28, 44.2% girls) completed the retest.

Measures

Behavioral Inhibition Questionnaire (BIQ; Bishop et al., 2003).

The BIQ assesses the frequency of children’s inhibited behaviors in six contexts, which are grouped into three main domains: social novelty inhibition (adults, peers, and performance) (e.g. “Is very quiet around new (adult) guests to our home”), situational novelty inhibition (new situations, separation/preschool) (e.g., “Quickly adjusts to new situations (e.g., kindergarten, preschool, childcare)”) and physical challenge (e.g., “Is confident in activities that involve physical challenge (e.g., climbing, jumping from heights)”). The BIQ has two versions, one for parents and the other for teachers. The parents’ version consists of 30 items, and the teacher’s version contains 28 items. Respondents classify items using a seven-point scale, ranging from 1 (almost never) to 7 (almost always). Ratings are summed up to create scores for each of the subscales (for the six contexts) and for the full scale. Items 2, 5–7, 9–11, 13–16, 19, 23–24, 26, and 29 in the parents’ version and items 2–3, 5–6, 8–10, 12–15, 18, 21–22, 24, and 27–28 in the teacher’s version should be reversed.

Temperament Assessment Battery for Children – Revised (TABC-R; Presley & Martin, 1994; Portuguese version, Almeida et al., 2010).

This scale measures two basic personality-behavioral dimensions in children: Inhibition and Impulsivity. To evaluate the convergent validity of the Portuguese version of the BIQ, we used the TABC-R inhibition subscale, which also has a version for parents and teachers. This inhibition subscale consists of eight items (parents’ version) and nine items (teacher’s version) that evaluate children’s inhibited behavior (e.g., “He is shy with adults he doesn’t know.”) which are scored on a seven-point rating scale. The Portuguese version of the TABC-R study showed internal consistency coefficients ranging from 0.64 to 0.86 (Almeida et al., 2010). In the present study, the TABC-R inhibition subscale presented good internal consistency, both in the parents’ version (Cronbach’s α = 0.83) and in the teacher’s version (α = 0.87).

Preschool Anxiety Scale (PAS; original version: Spence et al., 2001; Portuguese version: Almeida & Viana, 2013).

PAS is a parent-rated scale (28 items) measuring the level of anxiety of preschoolers (aged three to six years) in five dimensions: obsessive–compulsive disorder, social anxiety, separation anxiety, physical injury fears, and generalized anxiety. Parents are asked to rate the items from 0 (not true at all) to 4 (very often true) regarding their children’s level of anxiety. Although the whole scale was applied, we only used Social Anxiety (six items; e.g., “My child feels afraid that (s)he will make a fool of him/herself in front of people”), Separation Anxiety (five items; e.g. “My child worries about being away from us/me”) and the Generalized Anxiety (five items; e.g. “My child complains of feeling afraid”) subscales, since there is a stronger relationship between BI and the later development of these types of anxiety. The original Australian scale, as well as the Portuguese version, demonstrated very good internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging from 0.67 to 0.89. In the present study, alpha was 0.69 for the Generalized Anxiety subscale, 0.64 for the Separation Anxiety subscale, and 0.75 for the Social Anxiety subscale.

Procedure

Instrument Adaptation

After obtaining authorization from the BIQ authors to translate the questionnaire, two independent Psychology researchers, both native European Portuguese speakers, conducted the translation. Following Sousa and Rojjanasrirat’s (2011) recommendations, a bilingual expert performed the back-translation of the consensual Portuguese version, and necessary adjustments were made. Finally, a pre-test with two participants was performed to address any comprehension issues.

Data Collection

The data collection protocol was explained to the coordinators of each preschool institution. Informed consent and questionnaires (BIQ, PAS, and TABC-R) were delivered to parents in an envelope for completion at home. Once finished, parents returned the questionnaires to preschool teachers in a sealed envelope. Additionally, 157 parents (25.8%) agreed to participate in a retest by completing the BIQ online after a 30-day interval.

This study received approval from the Portuguese National Commission for Data Protection (CNPD) and the Directorate-General for Education (nº 6313/2016).

Data Analysis

The psychometric analysis of BIQ comprised item analysis, confirmatory factor analysis, measurement invariance analysis, as well as reliability and validity assessment.

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to examine the models suggested in the literature for the BIQ factor structure. Item skewness and kurtosis in both BIQ versions fell within the acceptable limits for normality (Finney & DiStefano, 2006), with skewness ranging from -0.59 to 1.51 and kurtosis from − 1.07 to 1.97. Nevertheless, Mardia’s tests detected significant multivariate non-normality (all p < 0.0001). Accordingly, the measurement factor models were estimated using the MLM procedure (ML estimation with robust standard errors and scaled test statistic), as recommended by Satorra and Bentler (1988, 1994), and implemented in R’s lavaan package (Rosseel, 2012).

Model goodness of fit was evaluated using various indices, including the chi-squared (X2) test, Comparative Fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). We used the robust version of these fit indexes, adjusted with the Satorra-Bentler scaling correction factor (Brosseau-Liard & Savalei, 2014). We evaluated the fit indices according to the recommended thresholds from Hu and Bentler (1999): RMSEA ≤ 0.06 and CFI and TLI ≥ 0.95.

To assess measurement invariance across gender and age groups, we conducted a series of tests, including configural invariance, metric invariance (factor loading invariance), and scalar invariance (intercept invariance). We omitted testing for strict invariance as residuals are not part of the latent factors and do not affect the interpretation of mean differences in the latent variables (Vandenberg & Lance, 2000). Fit criteria included the change in chi-square (Δχ2) and its associated p-value, considering that non-significant changes imply a good fit for the invariance model (Pauls et al., 2020). We also used the change in Comparative Fit Index (ΔCFI), recommended by Cheung and Rensvold (2002) as a less conservative yet viable index for model comparison in measurement invariance assessment; a ΔCFI smaller than 0.01 indicates invariance. When the indices present contradictory results, the decision was made based on the less conservative indicator, ΔCFI (Chen et al., 2005).

To assess the reliability of the BIQ scores, we computed Cronbach’s alpha and two indices based on model loadings: the Omega (ω), which informs the measurement precision with which a composite score (based on the items unit weighted sum) reflects the constructs contributing to it, and the Hierarchical Omega (ωh), which evaluates how precisely such composite score assesses just one specific target construct (Brunner et al., 2012). These omega coefficients are more suitable than Cronbach’s alpha for estimating the reliability of measures of hierarchically structured constructs. On the reliability domain, we also examined temporal stability (test–retest) using the observed test scores and assessed the agreement between parent and teacher reports.

To validity analysis, we calculated Pearson correlation coefficients to assess the convergence of BIQ scores with concurrent conceptually related measures.

Results

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

To examine the structure of the BIQ, we conducted separate confirmatory factor analyses for parent and teacher reports, considering four different measurement models: (1) a single-factor model, (2) a three-factor model with correlated factors, (3) a six-factor model with correlated factors, and (3a) a six-factor model with all factors loading onto a higher-order factor. Cross loadings and correlated residuals were not allowed in any of these models, and factor covariances were freely estimated.

Model 1 assumes that all items load onto a single dimension. While all items had significant loadings on this dimension, the fit indices suggested that this one-factor solution did not adequately explain the data (Table 1).

Model 2 proposes that the items clustered around three domains representing different contexts for BI (social novelty, situational novelty, and physical challenge). The factors showed strong correlations, except for the correlation between physical challenge and social novelty in the parents’ report. All items loaded significantly on the corresponding factors. Although Model 2 provided a significantly better adjustment than Model 1, the fit indices still indicated a poor fit.

Model 3 hypothesizes that the items clustered around six correlated contexts (peer situations, unfamiliar adults, performance, separation/preschool, unfamiliar situations, and physical challenge). Factors showed moderate to high estimated correlations, with all items significantly loading onto their respective factors, most of them having standardized loadings above 0.50. While Model 3 demonstrated a better fit than Model 2 in both parent and teacher reports, the fit indices still did not reach satisfactory levels.

The correlation pattern between the first-order factors supported a second-order factor model (Model 3a), although a Heywood case occurred for the parents’ data (the relationship between the second-order factor and the New Situation factor showed a standardized coefficient slightly above 1, resulting in a negative estimated variance). However, this negative estimate was statistically nonsignificant, likely due to sampling error rather (Dillon et al., 1987). Following Savalei and Kolenikov (2008) recommendation, we retained the estimated value of the variance. Since Model 3a proposes that the covariances between the six first-order factors are explained by a single higher-order factor representing general BI, the fit of this second-order model was expectedly worse than Model 3; however, the difference was minimal. Additionally, we calculated the target coefficient (Marsh & Hocevar, 1985), which indicated that the second-order general BI factor accounted for almost all of the covariance among the six BIQ contextual dimensions (the target coefficient was 0.98 for parent reports and 0.92 for teacher reports). The loadings of the factors on the higher-order factor were all significant and high. The loading of the New Situation factor on the general BI was notably high (close to one: parents = 1.01; teachers = 0.99), suggesting that New Situations and general BI may be addressing the same conceptual dimension.

Since none of the previous models yielded an optimal fit, we included a method factor, as hypothesized in the Introduction, encompassing all the reversed items that express disinhibition and greater social adjustment in the child (Model 4a).

Model 4a displayed a significantly better fit compared to Model 3a for both BIQ versions (Table 1). All items retained significant loadings on the BI factors, most exceeding 0.50. The reversed items exhibited small to medium-sized loadings on the method factor (ranging from -0.24 to -0.52 in the parent version and from -0.03 to -0.49 in the teacher version). Nevertheless, Model 4a still provides only a suboptimal fit for the data.

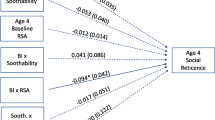

Modification indices suggested adding a covariance path between error terms for two items in the Performance domain (items 6 and 21 for the parent version, r = 0.49; and the corresponding items 5 and 20 for teacher version, r = 0.44). This modification resulted in an adjusted model (Model 4b; Table 1) both for the parent (χ2 (381) = 870.024, CFI = 0.902, TLI = 0.888, RMSEA = 0.060), and teacher versions (χ2 (328) = 729.982, CFI = 0.918, TLI = 0.905, RMSEA = 0.069). Standardized coefficient estimates for the final model of parents’ and teacher BIQ versions are provided in Figs. 1 and 2, respectively.

Factor structure and cross-gender and age invariance

To determine if the final structure model for BIQ differs by gender or age group (3–4 vs. 5–6 years), we conducted measurement invariance analyses using a stepwise multigroup comparison approach. Table 2 presents fit measures for gender invariance testing in both parent and teacher models. Configural invariance imposed no cross-group constraints (Model 1) and showed a satisfactory fit for the entire sample, indicating that the factor structure of BIQ was the same for both girls and boys. Metric invariance was tested by constraining all first-order factor loadings to be equal across gender groups (Model 2a). Results revealed a significant but non-substantial change compared to Model 1 (significant Δχ2 test), with minimal differences in CFI (ΔCFI = 0.002) for the parent version. For the teacher version, both the Δχ2 test (p = 0.139) and CFI differences (ΔCFI = 0.002) indicated that first-order factor loadings were invariant across gender. When cross-group equality on second-order factor loadings was imposed (Model 2b), we obtained a satisfactory fit for both BIQ versions. This suggests that the second-order factor loadings were equivalent, allowing for meaningful comparisons between boys and girls. Scalar invariance, tested by constraining all item intercepts to be equal across gender (Model 3), led to a significant reduction in overall model fit compared to Model 2b (Δχ2 tests for both versions, p < 0.001). However, the changes in CFI were not substantial (ΔCFI < 0.01), indicating no appreciable difference in item intercepts across genders for both the parent and teacher versions of the BIQ.

A multigroup comparison was also conducted to examine whether BIQ exhibits the same latent structure regardless of the child’s age (Table 3). For both the parent and teacher versions, the configural and the full metric invariance models showed a satisfactory fit, supporting the equality of first- and second-order factor loadings across age groups. When all item intercepts were constrained to be equal across different child age groups (scalar invariance), the model’s fit significantly deteriorated for both BIQ versions (Δχ2 test, p < 0.001). Nevertheless, due to minimal change in CFI (ΔCFI = 0.004), scalar invariance for age can be reasonably accepted.

In summary, BIQ features at least acceptable levels of measurement invariance (configural, metric, and scalar) across the male and female groups and age groups in the Portuguese preschool population, except for scalar invariance across age groups in the teacher version of BIQ.

Reliability

The reliability coefficients for the BIQ total score (computed through item unit weighted sums) and the six context scores are shown in Table 4. Internal consistency, as measured by Cronbach’s alpha (α), was found to be acceptable and good for all scores based on parent and teacher reports (α > 0.7), except for the parent-reported Physical Challenge score (α = 0.58).

Concerning omega reliability, the BIQ total score showed excellent levels (ω = 0.95 for parents and ω = 0.97 for teachers). The subscale scores also exhibited high reliability (ω > 0.7, often surpassing 0.8), except for the Physical Challenge score in the parent version (ω ~ 0.6; Table 4).

The omega hierarchical coefficient (ωh) allows for the determination of the contribution of each specific factor to the observed composite scores. The estimated proportion of variance attributed exclusively to the general BI factor was high for both versions of the BIQ (ωh = 0.74 for parents and ωh = 0.86 for teachers). The remaining proportion of variance was accounted for by specific BI contextual factors (ωh ~ 0.07 for both versions) and the reversed items method factor (ωh = 0.14 for parents and ωh = 0.04 for teachers). For the subscale scores, variance was primarily attributed both to the corresponding specific factor and the global BI dimension, with the method factor contributing the least (≤ 0.09). The specific factor often had a more substantial role than the general BI factor, although sometimes their contributions were nearly equal. This was particularly notable in the score for Adults and Physical Challenge in the parent version and the scores for Adults, Performance, and Separation scores in the teacher version. The New Situations subscale was mainly explained by the general BI construct (ωh = 0.71 for parents and ωh = 0.78 for teachers), with a large contribution from the method factor (ωh = 0.15 for parents and ωh = 0.08 for teachers). Similar patterns were observed for the Peers (in both versions) and the Physical Challenge scores (in the teacher version), but to a lesser extent.

In addition to the BIQ scores, two composite scores were also considered: social and situational inhibition. While these scores were not explicitly confirmed in our factor analysis, they have been used in the literature to assess the opposition between generic social and situational contexts (Spence, 2021). Both composite scores showed good internal consistency (α ≥ 0.88; ω ≥ 0.90). The Social Inhibition composite score had a substantial proportion of variance attributed to latent corresponding social contexts (ωh = 0.62 and ωh = 0.78 for parents’ and teacher versions). Similarly, the Situational Inhibition composite score had a significant amount of variance explained by latent situational contexts (ωh = 0.65 and ωh = 0.76 for parents’ and teachers’ versions).

The method factor’s contribution to the BIQ scores appeared to be more pronounced in the parents’ version (ranging from 0.02 to 0.16) compared to the teacher version (ranging from 0.00 to 0.08), but its impact on the score variance was small, mostly below 0.10. Consequently, we proceeded with analyses involving BIQ scores without explicit concern for controlling the noise introduced by the method factor.

Test–retest reliability was excellent, with ICC values ranging from 0.85 to 0.94 for the total BI score and subscales (Table 5). Pearson correlations demonstrated strong positive associations between scores at both assessment moments (r > 0.77) for all measures.

Relationship between BIQ Parent and Teacher Reports

The correlations between scores obtained from parent and teacher ratings were positive and significant (Table 6). Notably, the BIQ total score reported by both teachers and parents showed a moderate positive correlation (r = 0.42, p < 0.001). Apart from the Physical Challenge score, similar findings were observed for all the other BIQ subscales (0.31 ≤ r ≤ .43). The correlations between corresponding subscale scores in teachers’ and parents’ reports consistently showed higher values compared to correlations between non-corresponding subscales. This indicates that teachers and parents tended to provide similar assessments for the same BIQ subscales, supporting cross-informant reliability. However, it is important to note that correlations between non-corresponding subscales were also positive and significant, suggesting that the BIQ scores may have limited discriminatory ability.

Validity

To assess the convergent validity of the BIQ measures, we compared scores from parents and teachers on the BIQ with the TABC-R inhibition subscale (Table 7). The correlations between the scores were moderate to high, positive, and statistically significant for both the parent and teacher ratings, providing strong evidence for convergent validity. The only exception was the correlation between TABC-R inhibition and parents’ Physical Challenge score (r = 0.33, p < 0.001).

Significant positive correlations were observed between BIQ scores and the PAS social anxiety (0.30 < r < 0.77), PAS generalized anxiety (0.11 < r < 0.33), and PAS separation anxiety subscales (0.12 < r < 0.30) for both parents and teachers. These findings provide support for the construct validity of the BIQ scores, given the theoretical relationship between Behavioral Inhibition and anxiety symptomatology, particularly Social Anxiety.

Discussion

The objective of this study was to adapt the BIQ to the Portuguese language and evaluate its psychometric properties. The original BIQ, created by Bishop et al. (2003), reflects a six-correlated factor structure, which has been confirmed in studies conducted in different languages (Agostini et al., 2021; Broeren & Muris, 2010; Kim et al., 2011; Mernick et al., 2018). These factors reflect the different contexts in which children’s BI may occur, including unfamiliar adults, peers, performance, physical challenge, unfamiliar situations, and preschool/separation.

Our first goal was to replicate this factor structure in a sample of Portuguese preschool children. The rejection of the unidimensional model indicated that BI in this population, as measured by the BIQ, is a multidimensional construct. Furthermore, despite the BIQ's intent to represent the three domains of childhood BI (social novelty, situational novelty, and physical challenge), the three-factor measurement model did not fully capture the variability in responses. Therefore, further specification for the latent structure of the BIQ seems necessary. As in previous BIQ psychometric studies, the model with six contexts received stronger empirical support. This indicated that contexts such as the Separation/Preschool or the New Situations, for example, are distinct enough to warrant separate latent constructs associated with each of them, despite being part of the same Situational novelty domain.

A second-order factor was included in the model to represent the contribution of a general BI construct to the specific contexts (Bishop et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2011). Although all contexts exhibited high loadings on this general dimension, some unshared variability remained, indicating the specificity of the six first-order factors. Notably, the New Situations factor showed an extremely high loading, close to the boundary of the interpretable region, in both versions of the BIQ, a result consistently reported in previous psychometric studies (Bishop et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2011). The consistency across studies suggests that, according to parents and teachers, children’s reactions to new situations may be driven by their general BI temperament rather than being highly specific (Broeren & Muris, 2010). However, this might also be a characteristic feature of the questionnaire, given that the New Situations context is evaluated through very general items that could potentially overlap with other BIQ first-order factors. In one way or another, the BIQ’s New Situations subscale may not effectively stand out as a fully independent component of BI.

Despite limitations in model fit, the results support the notion that BI, as measured by the BIQ, is a higher-order construct with situational specificity in multiple contexts (Fox et al., 2005).

To account for the unexplained variability in participants’ responses, an orthogonal method factor was introduced to capture the impact of semantically reversed items in the BIQ (van Sonderen et al., 2013). Adding this method factor significantly improved the fit of the measurement model, suggesting that item wording, especially in the case of semantically reversed items, may lead participants (particularly parents) to respond to the BIQ items in a manner inconsistent with the intended content. While we cannot yet ascribe specific meaning to this method factor, reversed items might induce informants to adopt a social desirability or acquiescence bias response strategy (Podsakoff et al., 2012). Despite the significant contribution of the method factor to the model’s fit, the item loadings on this factor were relatively modest (with a median of 0.40 for the parent’s version and 0.27 for the teacher’s version), suggesting that its impact on the ratings may not be overly strong. We believe that including the method factor preserves the integrity of the BIQ’s theoretical model while shedding light on the potential impact of semantically reversed items in the questionnaire. Further research is needed to confirm the existence of this method factor, but our current results already indicate that item wording could influence responses to the BIQ.

The inclusion of covariance between two residual errors linked to the Performance factor was unplanned but deemed necessary to address item-specific content. This particular content related to enjoying versus disliking “being the center of attention”, which could be perceived as describing attention-seeking behavior rather than greater or lesser inhibition. Importantly, this adjustment, crucial for models tested on two separate groups of informants (teachers and parents), may represent a unique feature of the Portuguese BIQ version rather than an overfitting of the model to sample-specific characteristics.

Confirmation of full measurement invariance for gender (both in the parent and teacher versions) suggests that the BIQ latent structure and the meaning of BI scores are similar for boys and girls. While gender measurement invariance has been reported (Agostini et al., 2021), inconsistent findings regarding gender differences in BIQ scores were found (Bishop et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2011; Vreeke et al., 2013), possibly influenced by methodological or cultural factors, including gender roles and cultural stereotypes which can influence informants’ perceptions about BI. Further research is needed to fully understand the role of gender in individual differences in BI. Full measurement invariance for age was confirmed only in the parents’ version of the BIQ, indicating that the structure and meaning of BI measures reported by parents are similar across the two studied age groups. These results are congruent with the existing literature that characterizes BI as a relatively stable construct during childhood (e.g. Agostini et al., 2021; Möhler & Resch, 2018). However, the age range within a preschool population is inherently limited, and conducting studies with broader age ranges would be valuable to clarify BIQ measurement invariance across various stages of childhood (Besi & Sakellariou, 2019; Broeren & Muris, 2010; Möhler & Resch, 2018).

The reliability results for the parent and teacher versions of the BIQ were similar and satisfactory. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for BIQ scores were systematically above 0.70, indicating excellent internal consistency. However, Cronbach’s alpha may not be suitable for evaluating reliability in a complex, hierarchical measurement model. Therefore, a model-based reliability approach using omega coefficients was employed (Brunner et al., 2012), enabling us to weigh the contribution of each latent dimension to the variance in scores. The results demonstrated robust omega reliability, indicating that BIQ scores effectively captured the latent variables specified in the model (even after excluding the construct-irrelevant contribution of the method factor). However, when evaluating the reliability of the BIQ subscale scores as indicators of their specifically associated constructs, the omega hierarchical coefficients were notably lower. The presence of a general second-order BI factor accounted for a substantial portion of the variance in the subscale scores, resulting in relatively low omega hierarchical coefficients associated with the specific subscale constructs (below 0.53). Therefore, caution should be exercised when interpreting subscale scores as a reliable measure of BI in a specific context, given that these scores are mainly driven by the higher-order BI construct. It is worth mentioning that, consistent with previous validation studies, the reliability of the Physical Challenge subscale was the lowest in our study. These consistently lower results across all validation studies suggest that the Physical Challenge subscale differs qualitatively from the other BIQ subscales. This particular subscale stands out as the only one not primarily associated with the social aspects of BI and might be just capturing elements related to anxiety, specifically the fear of physical danger or body injury, rather than aspects of BI (Agostini et al., 2021). Future studies should explore the hypothesis of removing this motor component from BI, which may not adequately reflect the BI construct.

Since the contribution of the method factor to score variance was relatively small (never exceeded 16%), we proceeded with the temporal stability and validity analyses using the manifest item unit weighted sum scores, disregarding the potential nuisance introduced by the inclusion of reversed items.

The one-month test–retest reliability for the parent version was excellent, aligning with prior research (Agostini et al., 2021; Bishop et al., 2003; Mernick et al., 2018; Vreeke et al., 2013), reinforcing the temporal stability of the BIQ scores.

Intercorrelations between parent and teacher BIQ scores demonstrated cross-informant reliability. The correlations were positive and moderate (0.31 < r < 0.43), except for the Physical Challenge subscale. The partial overlap between parents’ and teachers’ behavior ratings may stem from behavioral differences across settings (home vs. preschool; Wray et al., 2013), or could result from some informants having less historical knowledge of the child (Takeda et al., 2016). Regarding the inconsistency in the Physical Challenge subscale, teachers may not have the same level of access as parents to the child’s daily life, where physically risky situations are more likely to occur. Overall, the partial agreement between parent and teacher reports supports using multiple informants for a more comprehensive understanding of preschool children's social-behavioral functioning (Bishop et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2011; Vreeke et al., 2012).

Evidence for the convergent validity was examined by comparing the BIQ scores with the TABC-R inhibition subscale. For both parents and teachers, TABC-R showed strong correlations both with the global BI score and all other BIQ scores (r > 0.5), except the Physical Challenge subscale in the parent version, confirming the validity of the BIQ as a measure of behavioral inhibition in children.

Considering the theoretical link between BI and social anxiety in children (Sandstrom et al., 2020), previous BIQ psychometric studies have employed a measure of social anxiety as an index of construct validity (Broeren & Muris, 2010; Mernick et al., 2018; Vreeke et al., 2013). In our study, the correlations between BIQ and the PAS social anxiety subscale were positive, although weaker compared to the correlations with the TABC-R inhibition subscale (0.3 < r < 0.6), as expected due to the related yet distinct nature of the constructs. Previous research has established links between Generalized Anxiety and Separation Anxiety and high levels of BI in childhood (Pini et al., 2022; Zdebik et al., 2022), so we extended the exploration of construct validity by examining the association between the corresponding PAS subscales and BIQ scores. The correlations were always positive and significant (0.2 < r < 0.4), particularly in contexts related to the Situational and Physical domains. Overall, these findings add to the evidence supporting BIQ’s validity.

Several limitations should be considered in this study. Firstly, the sample was predominantly collected from private and urban preschool institutions. Participating parents tended to be somewhat older and had higher educational levels, which could potentially limit the generalizability of our findings to the broader Portuguese population. Second, this study targeted normal, psychologically healthy children, so the psychometric properties of BIQ in clinically referred children remain to be established. Thirdly, retest ratings from teachers were not collected, which prevented the assessment of temporal stability for the teacher BIQ scores. Moreover, the factor analysis of teacher responses did not consider that the same teacher assessed multiple children in their classroom, assuming instead scores independence; although it is a common practice, more complex measurement models should be used to describe accurately the nested structure of this kind of data. Another limitation arises from the fact that either parent (mother or father) could complete the BIQ questionnaire, and for over one-third of the sample it was not possible to clarify who had filled it in. This prevented us from exploring potential differences in perspective between mothers and fathers. Lastly, our findings rely solely on questionnaire data. The inclusion of alternative assessment methods, such as observational measures and semi-structured diagnostic interviews, could have strengthened evidence for the convergent validity of the BIQ.

Despite these limitations, the present study confirms the BIQ’s good psychometric properties for assessing behavioral inhibition in Portuguese preschoolers. However, the questionnaire may have limited sensitivity in discriminating between different contexts where BI occurs, as the subscale scores showed high saturation in the general BI factor. This implies that interpreting the global BI score might be more reliable than relying on subscale scores as specific indicators of a child’s inhibition in specific contexts. The study also highlighted a potential bias in responding to reversed items, although with a relatively minor impact on BIQ scores. Nevertheless, BI assessment through this questionnaire might be influenced by spurious wording effects, which should be taken into consideration when interpreting the results. To build on these findings, future studies should further investigate the reliability of the BIQ subscales and explore the presence and impact of the method factor. Additionally, conducting studies with larger, more diverse samples, including school-age children and clinically referred populations, will provide more insights into BIQ’s psychometric properties across different contexts.

In summary, this study demonstrated that parents and teachers can provide valid and reliable reports of children’s BI, establishing the BIQ as a practical and cost-effective alternative to observational measures of behavioral inhibition. Furthermore, the BIQ Portuguese version has proven its suitability for evaluation and screening purposes in preschool settings, enabling the identification of children at risk of adverse outcomes associated with a highly inhibited temperament. In this sense, the current study reinforces the value of the BIQ in both research and applied settings.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Agostini, F., Benassi, M., Minelli, M., Mandolesi, L., Giovagnoli, S., & Neri, E. (2021). Validation of the Italian version of the behavioral inhibition questionnaire (BIQ) for preschool children. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(11), 5522. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115522

Almeida, J., & Viana, V. (2013). Anxiety in Portuguese preschool children - adaptation of the spence preschool anxiety scale. Psicologia, Saúde & Doenças, 14(3), 470–483. https://doi.org/10.15309/13psd140308

Almeida, M. M., Seabra-Santos, M. J., & Major, S. (2010). Bateria de avaliação do temperamento infantil – forma revista. Psychologica, 53, 313–328. https://doi.org/10.14195/1647-8606_53_15

Anaya, B., Vallorani, A., & Pérez-Edgar, K. (2021). Dyadic behavioral synchrony between behaviorally inhibited and non-inhibited peers is associated with concordance in EEG frontal Alpha asymmetry and Delta-Beta coupling. Biological Psychology, 159, 108018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2021.108018

Auday, E. S., & Pérez-Edgar, K. E. (2019). Limbic and prefrontal neural volume modulate social anxiety in children at temperamental risk. Depression and Anxiety, 36(8), 690–700. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22941

Ballespí, S., Jané, M. C., & Riba, M. D. (2012). The behavioural inhibition scale for children aged 3 to 6 (bis 3–6): Validity based on its relation with observational measures. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 34(4), 487–496. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-012-9305-6

Besi, M., & Sakellariou, M. (2019). Teachers’ views on the participation of parents in the transition of their children from kindergarten to primary school. Behavioral Sciences (Basel, Switzerland), 9(12). https://doi.org/10.3390/bs9120124

Bishop, G., Spence, S. H., & McDonald, C. (2003). Can Parents and Teachers Provide a Reliable and Valid Report of Behavioral Inhibition? Child Development, 74(6), 1899–1917. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1467-8624.2003.00645.x

Bourdon, J. L., Savage, J. E., Verhulst, B., Carney, D. M., Brotman, M. A., Pine, D. S., Leibenluft, E., Roberson-Nay, R., & Hettema, J. M. (2019). The Genetic and Environmental Relationship Between Childhood Behavioral Inhibition and Preadolescent Anxiety. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 22(1), 48–55. https://doi.org/10.1017/thg.2018.73

Broeren, S., & Muris, P. (2010). A Psychometric Evaluation of the Behavioral Inhibition Questionnaire in a Non-Clinical Sample of Dutch Children and Adolescents. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 41(2), 214–229. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-009-0162-9

Brosseau-Liard, P. E., & Savalei, V. (2014). Adjusting Incremental Fit Indices for Nonnormality. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 49(5), 460–470. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2014.933697

Brunner, M., Nagy, G., & Wilhelm, O. (2012). A Tutorial on Hierarchically Structured Constructs. Journal of Personality, 80(4), 796–846. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2011.00749.x

Carver, C., & White, T. (1994). Behavioral Inhibition, Behavioral Activation, and Affective Responses to Impending Reward and Punishment: The BIS/BAS Scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 319–333. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.67.2.319

Caspi, A., Moffitt, T. E., Newman, D. L., & Silva, P. A. (1996). Behavioral observations at age 3 years predict adult psychiatric disorders. Longitudinal evidence from a birth cohort. Archives of General Psychiatry, 53(11), 1033–1039. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830110071009

Chen, F. F., Sousa, K. H., & West, S. G. (2005). Testing Measurement Invariance of Second-Order Factor Models. Structural Equation Modeling, 12(3), 471–492. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328007sem1203_7

Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating Goodness-of-Fit Indexes for Testing Measurement Invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 9(2), 233–255. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5

Chronis-Tuscano, A., Degnan, K. A., Pine, D. S., Perez-Edgar, K., Henderson, H. A., Diaz, Y., Raggi, V. L., & Fox, N. A. (2009). Stable early maternal report of behavioral inhibition predicts lifetime social anxiety disorder in adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 48(9), 928–935. https://doi.org/10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181ae09df

Chronis-Tuscano, A., Novick, D. R., Danko, C. M., Smith, K. A., Wagner, N. J., Wang, C. H., Druskin, L., Dougherty, L. R., & Rubin, K. H. (2021). Early intervention for inhibited young children: A randomized controlled trial comparing the Turtle Program and Cool Little Kids. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 63(3), 273–281. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13475

Clauss, J. A., & Blackford, J. U. (2012). Behavioral inhibition and risk for developing social anxiety disorder: A meta-analytic study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 51(10), 1066–1075.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2012.08.002

Dillon, W. R., Kumar, A., & Mulani, N. (1987). Offending estimates in covariance structure analysis: Comments on the causes of and solutions to Heywood cases. In Psychological Bulletin (Vol. 101, Issue 1, pp. 126–135). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.101.1.126

Dodd, H. F., Rayson, H., Ryan, Z., Bishop, C., Parsons, S., & Stuijfzand, B. (2020). Trajectories of anxiety when children start school: The role of behavioral inhibition and attention bias to angry and happy faces. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 129(7), 701–712. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000623

Faísca, L., Ferreira, L. I., Fernandes, C. C., Gagne, J. R., & Martins, A. T. (2021). Behavioral Inhibition in Childhood: European Portuguese Adaptation of an Observational Measure (Lab-TAB). Children, 8(2), 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8020162

Feola, B., Armstrong, K., Woodward, N. D., Heckers, S., & Blackford, J. U. (2019). Childhood temperament is associated with distress, anxiety and reduced quality of life in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Psychiatry Research, 275, 196–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.03.016

Finney, S., & DiStefano, C. (2006). Nonnormal and categorical data in structural equation models. In G. R. Hancock & R. O. Mueller (Eds.), Structural equation modeling: A second course (pp. 269–314). Information Age Publishing.

Fox, N. A., Henderson, H. A., Marshall, P. J., Nichols, K. E., & Ghera, M. M. (2005). Behavioral Inhibition: Linking Biology and Behavior within a Developmental Framework. Annual Review of Psychology, 56(1), 235–262. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141532

Fu, X., Nelson, E., Borge, M., Buss, K., & Perez-Edgar, K. (2019). Stationary and Ambulatory Attention Patterns are Differentially Associated with Early Temperamental Risk for Socioemotional Problems: Preliminary Evidence from a Multimodal Eye-tracking Investigation. Development and Psychopathology, 31, 971–988. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579419000427

Glenn, A. L., Raine, A., Venables, P. H., & Mednick, S. A. (2007). Early temperamental and psychophysiological precursors of adult psychopathic personality. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 116(3), 508–518. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.116.3.508

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Jaffee, S. R., Moffitt, T. E., Caspi, A., Fombonne, E., Poulton, R., & Martin, J. (2002). Differences in early childhood risk factors for juvenile-onset and adult-onset depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 59(3), 215–222. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.59.3.215

Kagan, J., Reznick, J. S., Clarke, C., Snidman, N., & Garcia-Coll, C. (1984). Behavioral Inhibition to the Unfamiliar. Child Development, 55(6), 2212–2225. https://doi.org/10.2307/1129793

Kim, J., Klein, D. N., Olino, T. M., Dyson, M. W., Dougherty, L. R., & Durbin, C. E. (2011). Psychometric properties of the Behavioral Inhibition Questionnaire in preschool children. Journal of Personality Assessment, 93(6), 545–555. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2011.608756

Kochanska, G., & Radke-Yarrow, M. (1992). Inhibition in Toddlerhood and the Dynamics of the Child’ s Interaction with an Unfamiliar Peer at Age Five. Child Development, 63(2), 325–335. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01630.x

Lahat, A., Perez-Edgar, K., Degnan, K. A., Guyer, A., Lejuez, C., Ernst, M., Pine, D., & Fox, N. A. (2012). Early childhood temperament predicts substance use in young adults. Translational Psychiatry, 2(9), e157. https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2012.87

Lau, E. X., Rapee, R. M., & Coplan, R. J. (2017). Combining child social skills training with a parent early intervention program for inhibited preschool children. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 51, 32–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2017.08.007

Marsh, H. W., & Hocevar, D. (1985). Application of confirmatory factor analysis to the study of self-concept: First- and higher order factor models and their invariance across groups. Psychological Bulletin, 97(3), 562–582. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.97.3.562

Mernick, B., Pine, A., Gendler, T., & Shechner, T. (2018). A Psychometric Evaluation of the Behavioral Inhibition Questionnaire in a Non-Clinical Sample of Israeli Children and Adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(6), 1794–1804. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1027-2

Möhler, E., & Resch, F. (2018). Behavioral inhibition at five years is predicted by a short questionnaire in infancy. Mental Health and Addiction Research, 3(4), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.15761/mhar.1000168

Muris, P., Hendriks, E., & Bot, S. (2015). Children of Few Words: Relations Among Selective Mutism, Behavioral Inhibition, and (Social) Anxiety Symptoms in 3- to 6-Year-Olds. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 47(1), 94–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-015-0547-x

Muris, P., Monait, N., Weijsters, L., & Ollendick, T. H. (2021). Symptoms of Selective Mutism in Non-clinical 3- to 6-Year-Old Children: Relations With Social Anxiety, Autistic Features, and Behavioral Inhibition. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 2035.

Pauls, F., Daseking, M., & Petermann, F. (2020). Measurement Invariance Across Gender on the Second-Order Five-Factor Model of the German Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-Fifth Edition. Assessment, 27(8), 1836–1852. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191119847762

Pini, S., Abelli, M., Costa, B., Schiele, M. A., Domschke, K., Baldwin, D. S., Massimetti, G., & Milrod, B. (2022). Relationship of behavioral inhibition to separation anxiety in a sample (N = 377) of adult individuals with mood and anxiety disorders. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 116, 152326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2022.152326

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 539–569. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

Poole, K. L., Anaya, B., & Pérez-Edgar, K. E. (2020). Behavioral inhibition and EEG delta-beta correlation in early childhood: Comparing a between-subjects and within-subjects approach. Biological Psychology, 149, 107785. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2019.107785

Presley, R., & Martin, R. P. (1994). Toward a structure of preschool temperament: Factor structure of the temperament assessment battery for children. Journal of Personality, 62(3), 415–448. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1994.tb00304.x

Reznick, J. S., Kagan, J., Snidman, N., Gersten, M., Baak, K., & Rosenberg, A. (1986). Inhibited and Uninhibited Children: A Follow-Up Study. Child Development, 57(3), 660–680. https://doi.org/10.2307/1130344

Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

Salekin, R. T. (2017). Research Review: What do we know about psychopathic traits in children? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 58(11), 1180–1200. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12738

Sandstrom, A., Uher, R., & Pavlova, B. (2020). Prospective Association between Childhood Behavioral Inhibition and Anxiety: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 48(1), 57–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-019-00588-5

Satorra, A., & Bentler, P. (1988). Scaling corrections for chi-square statistics in covariance structure analysisProceedings of the Business and Economic Statistics Section of the American Statistical Association. Proceedings of the Business and Economic Statistics Section of the American Statistical Association, 308–313.

Satorra, A., & Bentler, P. (1994). Corrections to test statistics and standard errors in covariance structure analysis. In Latent Variable Analysis: Applications to Developmental Research (pp. 399–419).

Savalei, V., & Kolenikov, S. (2008). Constrained versus unconstrained estimation in structural equation modeling. In Psychological Methods (Vol. 13, Issue 2, pp. 150–170). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.13.2.150

Schiltz, H. K., McVey, A. J., Barrington, A., Haendel, A. D., Dolan, B. K., Willar, K. S., Pleiss, S., Karst, J. S., Vogt, E., Murphy, C. C., Gonring, K., & Van Hecke, A. V. (2018). Behavioral inhibition and activation as a modifier process in autism spectrum disorder: Examination of self-reported BIS/BAS and alpha EEG asymmetry. Autism Research: Official Journal of the International Society for Autism Research, 11(12), 1653–1666. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2016

Sousa, V. D., & Rojjanasrirat, W. (2011). Translation, adaptation and validation of instruments or scales for use in cross-cultural health care research: A clear and user-friendly guideline. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 17(2), 268–274. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01434.x

Spence, S. H. (2021). The Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale. https://www.scaswebsite.com/behavioural-inhibition-questionnaire/

Spence, S., Rapee, R., McDonald, C., & Ingram, M. (2001). The structure of anxiety symptoms among preschoolers. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 39, 1293–1316. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(00)00098-X

Stumper, A., Danzig, A. P., Dyson, M. W., Olino, T. M., Carlson, G. A., & Klein, D. N. (2017). Parents’ behavioral inhibition moderates association of preschoolers’ BI with risk for age 9 anxiety disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders, 210, 35–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.12.008

Suárez-Alvarez, J., Pedrosa, I., Lozano, L. M., García-Cueto, E., Cuesta, M., & Muñiz, J. (2018). Using reversed items in likert scales: A questionable practice. Psicothema, 30(2), 149–158. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2018.33

Suarez, G. L., Morales, S., Metcalf, K., & Pérez-Edgar, K. E. (2019). Perinatal complications are associated with social anxiety: Indirect effects through temperament. Infant and Child Development, 28(3), 2130. https://doi.org/10.1002/icd.2130

Takeda, T., Nissley-Tsiopinis, J., Nanda, S., & Eiraldi, R. (2016). Factors Associated With Discrepancy in Parent-Teacher Reporting of Symptoms of ADHD in a Large Clinic-Referred Sample of Children. Journal of Attention Disorders, 24(11), 1605–1615. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054716652476

van Sonderen, E., Sanderman, R., & Coyne, J. C. (2013). Ineffectiveness of Reverse Wording of Questionnaire Items: Let’s Learn from Cows in the Rain. PLoS ONE, 8(7), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0068967

Vandenberg, R., & Lance, C. (2000). A Review and Synthesis of the Measurement Invariance Literature: Suggestions, Practices, and Recommendations for Organizational Research. Organizational Research Methods, 3, 4–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442810031002

Vreeke, L. J., Muris, P., Mayer, B., Huijding, J., Bos, A. E. R., Van Der Veen, M., Raat, H., & Verheij, F. (2012). The assessment of an inhibited, anxiety-prone temperament in a Dutch multi-ethnic population of preschool children. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 21(11), 623–633. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-012-0299-0

Vreeke, L. J., Muris, P., Mayer, B., Huijding, J., & Rapee, R. M. (2013). Skittish, shielded, and scared: Relations among behavioral inhibition, overprotective parenting, and anxiety in native and non-native Dutch preschool children. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 27(7), 703–710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.09.006

Wise, S., Huang-Pollock, C., & Pérez-Edgar, K. (2021). Implementation of the diffusion model on dot-probe task performance in children with behavioral inhibition. Psychological Research Psychologische Forschung, 86, 831–843. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-021-01532-3

Wray, E., Shashi, V., Schoch, K., Curtiss, K., & Hooper, S. R. (2013). Discrepancies in parent and teacher ratings of social-behavioral functioning of children with chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome: Implications for assessment. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 118(5), 339–352. https://doi.org/10.1352/1944-7558-118.5.339

Zdebik, M. A., Pascuzzo, K., Bureau, J.-F., & Moss, E. (2022). Childhood behavioral inhibition and attachment: Links to generalized anxiety disorder in young adulthood. Frontiers in Psychology, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.933213

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge all participants in this study.

Funding

Open access funding provided by FCT|FCCN (b-on). Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT), SFRH/BD/112728/2015, Catarina Isabel Cova Fernandes.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design, as well as material preparation, data collection and analysis. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Catarina Cova Fernandes and all authors edited and commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval Code

6313/2016.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Portuguese National Commission for Data Protection (CNPD) and the Directorate-General for Education.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fernandes, C.C., Martins, A.T. & Faísca, L. Portuguese adaptation of the Behavioral Inhibition Questionnaire (BIQ). J Psychopathol Behav Assess 46, 235–251 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-023-10113-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-023-10113-0