Abstract

Wetlands provide ecosystem services such as flood protection, improved water quality, and wildlife habitat, but are under attack in urban land-use conflicts in the Global South. This article presents two cases of local wetlands governance conflicts in Colombia (Humedal la Conejera, Bogotá, Cundinamarca) and Argentina (Laguna de Rocha, Esteban Echeverría, Gran Buenos Aires) to illustrate divergent pathways toward improved environmental governance via citizen pressures: the collaborative method (Bogotá) and the adversarial method (Buenos Aires). While existing scholarship on citizen-led regulation stresses the importance of collaboration between community organizations and the state, this article argues that adversarial tactics are also a key component of environmental governance. In both cases, citizen-led pressures led to increased enforcement of regulatory measures to restore wetlands and gain protected-area status. Citizen-led governance involved adversarial strategies such as marches, litigation, and shaming and blaming in the media, as well as collaborative strategies such as creating broad-based educational forums, working inside city government, and partnering directly with public institutions to set new policies. Against the backdrop of extensive collusion between elected officials and land developers, citizen-led subnational environmental governance has become the regulatory regime of last resort in urban Latin America.

Similar content being viewed by others

Subnational enforcement of environmental regulations is a determinative factor in environmental outcomes in Latin America. In federal systems, provincial governments draft forest land-use regulations, push them through local legislatures, and oversee them through veto and decree powers (Milmanda and Garay 2020, 8). Provincial governments can be critical in innovating new laws, such as banning open-pit mining (Urkidi and Walter 2011, 692), or in enforcement of existing laws, such as those regulating deforestation (Alcañiz and Gutierrez 2020, 56). For better or worse, subnational elected officials even have tremendous discretion in the declaration of environmental disasters or protected areas (Cooperman 2022; Kopas et al. 2021). Subnational governments are also frequently the target of pressure from business groups seeking to curb environmental protections that harm their bottom line; business actors or their family members frequently hold elected office (Milmanda and Garay 2020; Amengual 2016; Madariaga et al. 2021, 1183–84, 1186).

Yet in the context of weak institutions, strong economic interests, and politicized bureaucracies, environmental regulations are frequently skirted or unenforced. This article examines the role of civil society in co-producing environmental regulations and enforcement mechanisms in the Global South. I compare two cases of local wetlands conflicts in Latin America (Humedal la Conejera, Bogotá, Cundinamarca in Colombia; and Laguna de Rocha, Estevan Echeverría, Gran Buenos Aires in Argentina). In both cases, citizen pressures led to increased enforcement of regulatory measures to restore wetlands and gain protected-area status. Local and subnational institutions varied in their response to land-use conflicts; some institutions defended development interests while others advanced environmental protection measures. Citizen organizations used diverse tactics such as administrative petitions, judicial proceedings, and shaming and blaming through the media to pressure institutions to comply with their legally mandated obligations. Ultimately, civil society organizations played an active role in subnational environmental regulation by inventing, activating, and pressuring institutional arrangements to protect wetlands, it is against this backdrop that local environmental institutions were wholesale created. Unlike the emphases of other papers in this special issue, pre-existing differences in local government capacity does not explain the variant pathways and outcomes emphasized here, instead the strategies and capacities of civil society organizers shaped wetlands policy and improved regulatory quality. The cases show how civil society can help close “implementation gaps” related to regulations that look good on paper but remain unfulfilled.

The article next reviews existing literature on citizen-state co-governance before outlining the case selection strategy and methods used. The case studies illustrate two pathways for subnational environmental governance. First, I examine the Buenos Aires case (the adversarial method), before turning to the Bogotá case (the collaborative method). These cases suggest that citizen-led environmental governance is not an aberration from Weberian bureaucratic autonomy but rather a necessary tool for activating institutional capacity in weak institutional settings. Citizen-led environmental governance speaks to the proactive policymaking outlined in the Introduction of this special issue. Existing scholarship has emphasized that greater levels of state-society collaboration is key to improved environmental regulations. I problematize this insight by identifying multiple pathways toward improved regulations, one of which entailed minimal collaboration and greater levels of adversarial pressure. Due to unregulated land-development regimes that are backed by local political leaders, citizen-led subnational environmental governance is frequently the regulatory regime of last resort in urban Latin America.

Citizen-Led Environmental Governance: Collaborative versus Adversarial Pathways to Institution-Building

The idea that public policy problems should be regulated with the input of societal forces has emerged in many different fields. In the US and European contexts, public administration scholars have developed the concept of “collaborative governance,” where public agencies directly engage with non-state stakeholders in decision-making processes (Ansell and Gash 2008, 544–47). The concept of collaborative governance has been a corrective to downstream policy failures involving high costs and politicization. Collaborative governance is seen as “an alternative to the adverserialism of interest group pluralism” (Ansell and Gash 2008, 544), as it is premised largely on achieving legitimacy through deliberation and having “participatory roots” (Fung 2006; Berkes 2009, 1693). One study defines collaborative governance as necessitating principled engagement, shared motivation, and capacity for joint action (Emerson et al. 2012, 6). Other similar terms include interactive governance, co-management, co-governance and co-production (Birnbaum 2016, 306–7; Berkes 2009; Plummer and Armitage 2007; Ostrom 1996, 1078–82).

This article further develops the concept of citizen-led environmental governance, a particularly relevant category for understanding environmental problems in weak institutional settings. Environmental regulations in Global South countries differ from Northern countries in numerous ways, such as having imported rather than home-grown regulatory models, limited bureaucratic autonomy, a dearth of civil service programs, struggles for resources and political support, and a tendency towards institutional development as opposed to maintenance tasks. Furthermore, regulatory institutions in the Global South may be overseeing sectors that are experiencing “wholesale creation” (Hochstetler 2012, 368).

Scholars have documented how environmental governance in decentralized settings of the Global South can feature strong community involvement. As forms of “collaborative governance,” often referred to as “participatory institutions,” state officials and civil society members have acted collectively to co-govern for example, river-basin committees (Abers and Keck 2013) and river pollution cleanup committees (Herrera and Mayka 2020), noting that “participatory decision-making forums can be important arenas for connecting and activating the state-society networks that help build state capacity” (Abers and Keck 2009, 293). In contrast to confrontational mobilization, participatory institutions such as citizen advisory councils can be more enabling and accommodationist (Hochstetler and Keck 2007, 45).Footnote 1

Within environmental governance, regulation is often more difficult to achieve than institution-building. Collaborative or participatory arrangements, often tasked with decision-making around natural resource withdrawals and administrative caretaking (including financing), may not always be involved in regulatory enforcement. Here I refer to regulation as a rule-based process that involves an institutional authority with power to impose fines or punitive measures to promote compliance with rules. If environmental regulations are meant to protect public health and the environment from pollution by industry and development, what role do civil society groups play in environmental regulation within weak institutional settings?

While the crux of bureaucratic autonomy is insulation from political influence, paradoxically the effectiveness of the regulatory state in the Global South has been linked to its ties to civil society (Hochstetler 2012, 367). Full-grown Weberian regulatory agencies have rarely developed in the Global South to match imported global models; institutions with weak enforcement or instability of rules are more common (Levitsky and Murillo 2009, 117; Hochstetler 2012, 363). Civil society has thus had a major role in shaping the contours of Global South regulatory regimes, particularly for environmental resources (Hochstetler 2012, 363; Lemos and Agrawal 2006, 310). In Vietnam, where protests are illegal and there are no competitive elections, communities nevertheless identified environmental problems and pressured both firms and the state to reduce pollution. In fact, “Community action was the key dynamic underlying state actions and corporate initiatives to reduce pollution” (O’Rourke 2002, 98). In Argentina, Amengual documented how societal groups can achieve effective regulatory enforcement by providing regulatory institutions with resources they may lack, such as information, material resources, political support, technical capacity, and operational support (2016, 29–33). Amengual distinguishes between society-dependent enforcement where societal pressures can replace the state, versus co-produced enforcement where societal pressure works in tandem with bureaucracy to build higher levels of regulatory capacity (2016, 36–37). These studies emphasize the importance of collaboration between community groups and environmental regulators.

This article contributes to previous work on environmental governance by arguing that citizen-led environmental governance can feature collaboration but also adversarial pressure; indeed, the latter may sometimes be an important tool for shaping subnational environmental institutions. In both cases of environmental governance examined here, local environmental groups have worked to (1) secure an official wetlands and protected-area designation, (2) construct legislation and a governing institution with resources and increased enforcement will, and (3) gain a recognized seat at the governing table. This theory-building article systematically compares two pathways that emerged in the construction of urban wetlands governance. The first featured collaboration (or enabling strategies) in the Bogotá case, and the second, adversarial (or blocking strategies) in the Buenos Aires case. The collaborative strategy the Bogotá groups undertook benefitted from a greater number of linkages between civil society and local government institutions and a greater number of venues and strategies through which to make their claims. In contrast, the Buenos Aires’ groups had fewer linkages with local institutions and utilized a smaller number of venues and strategies to press their claims. Despite the differences in the two pathways, both cases of urban wetlands mobilization helped push for the creation of new subnational institutions and helped activate existing ones to engage in environmental oversight and regulation.

Case Selection and Methods

The politics of urban wetlands have been virtually ignored by environmental politics scholars, but are critical to urban resource governance. Urban wetlands are directly tied to climate resilience and environmental disaster management. Urban wetlands provide flood control, migratory species habitats, and recreational green spaces. Expansive real estate speculation, industrial and commercial developments, and urbanization have transformed Global South cities, eroding urban wetlands and their capacity to provide flood regulation (Hettiarachchi et al. 2015, 62; Mintah et al. 2021, 1–2). Wetlands appropriations are politically complex conflicts that often involve urban land-grabbing and dispossession due to unregulated real estate expansion (Hettiarachchi et al. 2019, 742–43). These activities exacerbate environmental risk via altered water tables and exposure to contaminated wastewater (as wetlands are frequently used for wastewater dumping). In flood-prone areas amid a changing climate, entire neighborhoods can quickly become disaster zones.

I select two urban wetlands that are proximate to major metropolitan regions and capital cities in Latin America: Bogotá and Buenos Aires. Both cases fall are “aspiring global cities” (Pasotti 2020, Ch. 4), where real estate development spurred by global capital, industrial development, and haphazard residential expansion has outstripped the state’s provision of public services. Land-use conflicts are therefore intense political battles that pit forces of pro-development regimes against environmentalists and housing movements. In the midst of intense housing crises where neighbors are in dire need of access to both new accommodations and upgrades to existing accommodations, developers eye low-value flood zones as attractive money-makers that can easily pass votes in City Councils eager to generate tax revenue. The entry costs are low, but the social impact is high. Here, citizen battles to slow down speedy zoning decisions and press governments to properly study, regulate, and govern ecosystems take shape. The politics of co-production of regulation thus become a critical tool against climate change and its most deleterious effects in Latin American cities.

The purpose of this theory-building paper is to trace two pathways toward the co-production of subnational environmental regimes. In this process-tracing “pathway” argument, I prioritize causal process observations and thick description (Gerring 2012) to argue that multiple pathways of contention and collaboration can lead to increases in urban environmental regulation. Although the paper compares two cases with important differences, the emphasis is on process tracing to uncover the pathway mechanisms and characteristics that adversarial versus collaborative forms of citizen-led regulation take. These process-tracing exercises highlight the similar steps taken in co-producing environmental regulations via citizen pressures within the two cases, in order to further develop the concept of citizen-led environmental governance.

I leverage evidence from a wide range of sources, including approximately fifty-six interviews in Bogotá and Greater Buenos Aires in 2016 and 2017. Most interviews (over 90 percent) were semi-structured with a questionnaire, while a small handful were unstructured. All interviews were recorded, and I produced typed interview notes for each interview, with a smaller number of interviews transcribed. Interviews ranged from twenty minutes to two hours, the average length being approximately seventy minutes. Interviewees were drawn from civil society organizations, city and provincial agencies, the judiciary, and academic experts in Colombia and Argentina (see Appendix for full list). Process-tracing also relied on a compilation of numerous text-based sources, including newspaper articles, materials created by civil society organizations, and government documents. Sometimes political actors’ positions were gleaned through Twitter and other social media platforms, which were triangulated with additional text-based sources and interview data.

Adversarial Pathways to Subnational Environmental Institution-Building in Argentina

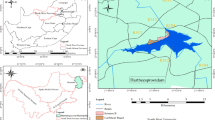

The Rocha Wetlands (Laguna de Rocha) are marshlands located across a 1400-hectare territory in a provincial district of the Buenos Aires Metropolitan Area called Esteban Echeverria whose capital city is Monte Grande. It is the region’s largest green space and helps provide flood control for the Matanza Riachuelo River (di Pangracio Undated).Footnote 2 Rocha’s viability has been threatened through many land-use conflicts arising from the monocultivation of soybeans, real estate speculation, industrial use permitting, sports stadiums development, and open-air trash dumping. As the municipal and provincial government have neglected responsibility for the Rocha Wetlands, civil society groups have mobilized to lobby for improved environmental regulations and new subnational environmental institutions. The Rocha case illustrates how citizen-led adversarial regulation may sometimes be the only route to subnational environmental institution-building and environmental stewardship in hostile political and economic settings.

Laguna de Rocha: Industrial Warehouses, Sports Complexes and Toxic Herbicides in Esteban Echeverría, Buenos Aires Metropolitan Area

Due to its ambiguous legal standing—stemming from competing ownership claims from the federal government, the city, and private sector—the Rocha Wetlands has been home to numerous real estate battles, most notably involving industrial-use permits and sports complex developments. In 2008, the Esteban Echeverría City Council approved a “Type 1” industrial-use permit for a low-pollution warehouse development on 10% of the wetland territory. The measure passed during a late-night, closed-door, council meeting that ended in violence; in 2009 city council allowed for a “Type 2” industrial-use permit, permitting higher pollution industries and more lucrative (and environmentally destructive) land development.Footnote 3 Creaurbana, real estate company behind these land developments in Rocha,Footnote 4 was owned by Angelo Calcaterra—a politically connected cousin of Mauricio Macri (Buenos Aires Mayor 2007–2015, and Argentine President, 2015–2019). Calcaterra had donated to both President Kirchners’ electoral campaigns and would become ensnared in the 2018 Odebrecht corruption scandal.Footnote 5 When these projects were overturned following popular opposition and social mobilization, Calcaterra began growing monocrop soybeans on the Rocha Wetlands, which involved slash-and-burn fires to clear fields and mass sprayings of the toxic herbicide glyphosate.

Against this contentious backdrop, a 64 hectare portion of the wetlands was ceded to two national soccer clubs: Boca Juniors in 2009 and Racing in 2011 (Terraviva 2021 and FARN, p. 3; and Colectivo Ecologico 2020, June 25).Footnote 6 These soccer clubs were politically well-connected: President Nestor Kirchner was a Racing megafan, and the land was ceded by executive decree. Although Boca Juniors canceled its project in the Rocha wetlands in 2013 after land conflicts led to judicial injunctions, Racing started construction amid significant public opposition.

Civil Society Organizes to Demand Environmental Regulations

Community interest in defending the Rocha Wetlands began in the mid 1990s with small actions that the city was initially able to shut down. In 1995, natural sciences professor Natalia Mastrocello and her colleagues published a paper arguing that untreated wastewater sewage runoff was turning the Rocha Wetlands into an anaerobic pond that was inhospitable to wildlife (Caruso 2021). The Municipal Historic Studies Committee also documented that indigenous (Querandíes) battles took place on Rocha territory in the sixteenth century. These studies helped pressure the municipality to declare the Rocha Wetlands a Municipal Historical Reserve in 1996.Footnote 7 Mastrocello and city official Pablo Pila conducted the first known Rocha Wetlands survey and catalogued diverse flora and fauna.Footnote 8 One activist noted that, “[They] began to plead that there not be further urbanization around the lands surrounding the wetlands, but were threatened and removed from their jobs.”Footnote 9 According to activists, Mastrocello and Pila were met with political resistance because the city was trying to sell the lands.Footnote 10 Mastrocello continued to publish information about the Rocha Wetlands online, but her attempts to draw broader attention to wetlands preservation waned.

The Esteban Echeverría City Council’s decision in 2009 to issue industrial use permits in the wetlands ignited a strong social backlash and prompted civil society activists to advocate for improved environmental regulations and governance. The Rocha Collective (Colectivo Ecológica Unidos por la Laguna de Rocha)—a group of primarily middle-class residents with ties to the fields of education or birdwatching—initiated a series of protest actions aimed at City Council members. The Rocha Collective began leading day trips and overnight camps to educate the community about the wetlands’ vulnerability and to recruit new members. One member recalled, “We wanted to break the cycle and say, this is not a private space (owned by politicians treating it as private land)—this space is public and belongs to the community.” A rally in front of the mayor’s office in November 2009 brought out more than twenty civil society organizations and gained extensive local news coverage. One activist noted that “all of a sudden, the Rocha Wetlands had become a cause.”Footnote 11

The Rocha Collective papered downtown Monte Grande with posters featuring scratched-out photographs of the City Council members who had voted for the industrial use permits, and then alerted newspapers for maximum coverage. The Rocha Collective’s strategies were so successful that they led the City Council to rescind the Type 2 industrial-use permit for the Rocha Wetlands in 2010. One activist explained, “We had found city council’s weakness—they didn’t like to be exposed.”Footnote 12

The Rocha Collective’s main objective was to have the Rocha Wetlands legally protected from commercial and industrial development, be declared a natural reserve with a management plan, and be co-governed by local authorities with civil society input. Diverse strategies helped grassroots organizations recruit members, develop alliances, and better understand the local political terrain. Public visits, tours, and corpachadas (an Andean ancestral ritual involving food offerings to Mother Earth) helped expand interest in Rocha as a public, communal space with diverse ecosystem services.Footnote 13

Protest strategies involved handing out flyers in urban areas with lists of the political attacks on the wetlands, organizing downtown demonstrations with large posters of the wetlands, and marches and rallies. While the Rocha Collective had ten to fifteen core members, they mobilized larger numbers at rallies due to their alliances with other organizations. The Rocha Collective developed these ties by attending other environmental protests across the Greater Buenos Aires province, such as those for the Santa Catalina wetlands, in Tigre, González Catán, and for the Intercuencas group for Riachuleo, Reconquista and Rio de la Plata (RRR). Later, members of those same organizations attended Colectivo’s demonstrations in Esteban Echeverria in support of the Rocha wetlands.Footnote 14

Grassroots pressure included freedom of information requests to increase transparency and to bring recalcitrant public officials to the bargaining table. In 2010, the Rocha Collective began filing reports with a federal judge that provided detailed information with photographic evidence about encroachment on the Rocha Wetlands; the Wetlands were connected to the Matanza Riachuelo River on which there was a 2008 federal ruling for remediation. Aided by prominent environmental attorney Enrique Viale and the Argentine environmental NGO Fundación Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (FARN), the Rocha Collective began filing freedom of information requests for financial records related to the Rocha Wetlands; after months of government stalling, FARN filed an amparo (a constitutional protection lawsuit) for the information. The Rocha Collective leaders recalled that “When we began to request information, it began to make people uncomfortable.”Footnote 15

Citizen-led regulatory actions also included litigation and the submission of evidence to the courts. In 2010, a smaller grassroots group named Neighbors of the Atomic Center (Vecinos al Centro Atómico) filed an amparo for Rocha Wetlands protection with the Environmental Assembly of Esteban Echeverría (Asamblea Ambientalista de Esteban Echeverría).Footnote 16 Reports and photographic evidence from the Rocha Collective aided the National Ombudsman’s Office as it also filed an amparo in 2011 against the Esteban Echeverria municipality, the Provincial Environmental Regulatory office (OPDS), and the Matanza Riachuelo Riverbasin Authority (ACUMAR) to protect Rocha. This amparo caused the judge overseeing the implementation of the Matanza Riachuelo River remediation ruling to begin organizing meetings with provincial and municipal public officials and the Ombudsman’s Office. In 2015, the Rocha Collective submitted more reports about illegal fires and unmonitored open dumpsites on the Rocha Wetlands, which resulted in investigations from the same federal judge and the Ombudsman’s Office. After further stalling by authorities, in 2016, the Rocha Collective presented a complaint to Argentina’s Anti-Corruption office regarding corruption and threats of violence against activists by park rangers assigned to manage the wetlands.

Citizen Pressures and Co-creating Subnational Environmental Institutions

This case demonstrates how social mobilization can help city officials co-create subnational environmental institutions in a municipality where public officials are recalcitrant or ambivalent about environmental issues. When Pablo Pila, Esteban Echeverría’s first Coordinator of the Environment, began investigating contamination and illegal dumping on the Rocha wetlands in the mid-1990s, the city shut down the municipal Environmental Office of Esteban Echeverría altogether.Footnote 17 During the 2009 social mobilization against the Industrial Use Type 2 industrial-use permit on Rocha territory, civil society groups demanded that the city form a new Environmental Office. Bowing to public pressure, the city reopened the office in 2009, elevating it to a Secretariat.

In 2012, grassroots mobilizing by the Rocha Collective and its allies in the Ombudsman’s Office and NGO FARN paid off: the Provincial Legislature passed Law 14.488, declaring Rocha to be a Natural Reserve with Integral and Mixed Use.Footnote 18 Leading up to that victory, activists and allies had researched different options at multiple tiers of government and internationally to press authorities to craft environmental institutions that could protect the wetlands. Argentina’s National Parks system would not accept the Rocha territory, arguing that it was too small, contaminated, and urban to fit the requirements in the National Natural Reserves’ law. Ramsar International was also unable to make Rocha a Ramsar site (an internationally recognized wetland) due to competing land ownership claims in Rocha from private developers, the need to expropriate land from private owners, and the lack of a functioning management plan. Thus, activists settled for targeting provincial legislators and launched a campaign of letter-writing, emails, and cyber actions to pressure politicians and build political relationships. The highly publicized 2009 protests helped to turn municipal leaders toward supporting the campaign to create a provincial Rocha reserve. As one Rocha Collective member explained:

Socially, things became too tight—pressured. [Elected officials] couldn’t keep avoiding the issue of the Rocha wetland. Because at that point at the province there were too many [politicians] who were…[committed]. It was no longer politically convenient to [oppose the legislation].Footnote 19

After negotiations over pre-existing private land ownership and over where to carve out a contiguous area for protection, 700 hectares became protected in a unanimous vote in the Buenos Aires provincial legislature. After delays in implementation, the governor “promulgated the law” in 2013. There were problems with this law: it did not specify a management plan and it retained protections for some pre-existing private owners. Activists learned from nearby Santa Catalina Wetlands conflicts, where hard-fought natural reserve laws became inoperable due to the continued presence of private landowners. The Rocha activists avoided the thorny question of appropriation and urged the local government to turn the wetlands into a mixed-used space. One activist explained, “We had to get this done, even if it was imperfect.”Footnote 20

Environmentalists achieved a major legislative win from the 2012 Natural Reserve law when it established a participatory institution that would “co-govern” the reserve. Article 2 of Law 14.48 required the wetland have a governance committee (Comité de Gestión) led by the mayor of Esteban Echeverría that would convene national representatives, provincial institutions, and civil society organizations. This created an institutional requirement that “residents with authority” would be included in the management of the reserve.Footnote 21

Thus began a battle with the provincial environmental agency (OPDS), which never wanted responsibility for the reserve because it required personnel and budgetary resources, which the state saw as financially burdensome. Activists and the Ombudsman’s Office petitioned the provincial government to create a management plan and take responsibility, but the state ignored requests for meetings. When the Comité de Gestión began to meet, the OPDS attended a few times and then stopped attending altogether. Residents complained that OPDS was shirking its responsibilities.Footnote 22 Meetings were hostile, and progress stalled because OPDS blocked the creation of a management plan for Rocha for several years. By 2016, pressure from the presiding federal judge helped push forward a management plan.

Civil society groups replaced the state’s environmental oversight responsibilities in many instances in the Rocha case. Grassroots organizations continued to document violations of the area’s Natural Reserve status and took their claims to authorities within the judiciary, the Ombudsman’s Office, and the Anti-Corruption Office—effectively circumventing the recalcitrant provincial government. With help from the Ombudsman’s Office, the Rocha Collective filed freedom of information requests to investigate the use of state funds, reports with the Anti-Corruption Office, and reports to the judge overseeing the Matanza Riachuelo case. They recorded the presence of illegal trash dumping, fires, tree removal, the private sale of plants grown on the reserve, squatting, and complicity by provincial officials and the park ranger. The Rocha Collective and other groups organized marches to garner attention, including a march to the OPDS’s office in 2019.Footnote 23

Building Subnational Environmental Institutions Through Adversarial Strategies

There are multiple pathways for activists who engage in co-constructing environmental institutions with the state. The case of Laguna Rocha illustrated how environmental activists used adversarial strategies to help build subnational environmental regulations and place pressure on public officials to enforce them. First, activists were primarily outsiders as opposed to insiders in terms of their interaction with the state. Neither activists nor their allies (NGOs, attorneys, or Ombudsman’s Office officials) became part of government agencies. Nor did Rocha activists develop close ties with bureaucratic insiders in the local and provincial government. Their ties were context-specific, such as when they coordinated with a handful of lawmakers to get the 2012 Reserve Law passed.

Second, Rocha activists were faced with obstructionist governments, which revved up their adversarial strategies. Many City Council members had ties to groups that supported development on Rocha wetlands, such as soccer clubs and industrial warehouse developers. Officials within the provincial environmental agency were loath to enact a management plan and expend resources on Rocha even after the 2012 law passed. Thus, activists used the courts and Ombudsman’s Office to create pressure for action at the provincial level. In addition, Rocha activists did not find allies within City Council until they used adversarial strategies that received extensive press coverage. Activists spent much more time developing relationships with newspaper outlets and refining their social media strategies than in cultivating relationships with political elites behind closed doors. Activists characterized their relationship with City Council and the long-time mayor as a “marriage of convenience,” due to the province’s disdain for Rocha caretaking responsibilities and the municipality of Esteban Echeverría’s disdain for the province.

Thus, Rocha activists adopted adversarial strategies for shaming and blaming public officials in order to push their agenda regarding environmental protections. Activists sought media access, giving many interviews to newspapers, radio stations, and blogs; maintaining multiple social media accounts; developing a blog that served as a news outlet; and helping support the creation of a documentary that enjoyed European release. Environmentalists took direct actions, such as marches, rallies, and demonstrative signage and graffiti. Grassroots organizations also brought in non-local allies through litigation, freedom of information requests, and Anti-Corruption Office complaints.

Environmentalists in the Rocha case faced many setbacks and have not achieved all their goals: the wetlands still lack a management plan, the Comité de Gestión still lack active participation by the province, and private sector interests continue to attack some portions of the wetlands. Yet citizen-pressured regulation has been the critical piece to achieving some subnational environmental institution-building. These actions have also helped change the regional debate about local land conflicts and the benefits of environmental public goods in places with aggressive real estate speculation. Thus, it is now much harder for subnational officials to make hidden development deals in what is now widely considered to be public collective lands with critical ecosystem services.

The political benefits of environmental stewardship have even spilled over into a once-recalcitrant mayor’s office. Fernando Gray, the longtime mayor of Esteban Echeverría, became president of the regional international consortium of South American cities (Mercociudades) in 2021 and declared his platform to be one of environmental sustainability. International networks, in the face of a united and vocal local environmental movement with ready media access, enticed Mayor Gray to ask the federal government to move the Racing soccer club development project out of the Rocha wetlands in 2022. Subnational environmental institution-building will continue to unfold in Esteban Echeverría and the province of Buenos Aires, but it is likely to stay afloat only with ongoing oversight from citizen-led movements. In contrast, the following case illustrates a more collaborative pathway to subnational institution-building that achieved significant policy outcomes in a much less hostile context.

Collaborative Pathways to Subnational Environmental Institution-Building in Colombia

In the early 1990s, Conejera, like all of Bogotá’s wetlands, was a dumping site for construction debris. Yet decades later, it had received protection status at the urban and national level, even becoming an internationally designated Ramsar site. Civil society groups mobilized to pressure for environmental regulations and the creation of new subnational environmental institutions in the face of attacks on the city’s wetlands. Unlike the Rocha case, citizen groups won important early victories against real estate development and collaborated with numerous government agencies on wetland improvement projects and on co-governing the green space. This case illustrates the process and conditions that undergird citizen-led collaborative regulation when activists directly penetrate local institutions and build broader networks of support.

El Humedal la Conejera: Real Estate Speculation and Wastewater Reservoirs in Suba, Bogotá

The Conejera Wetlands (Humedal La Conejera) are freshwater marshes on nearly 60 hectares in the Juan Amarillo River basin in the locality of Suba, Bogotá metropolitan region. Colombia has over 31,000 wetlands and an estimated 87% of the country’s population resides in wetlands areas. The Conejera wetlands are one of eleven urban wetlands that regulate water supply from the rivers of the Bogotá savanna. They provide flood control and a crucial ecological connector between urban and rural territories. Over 190 bird species have been recorded there, including some that were once considered extinct.Footnote 24

Bogotá’s wetlands have historically been threatened by wastewater and unregulated real estate development. Bogotá’s wetlands have declined from 50,000 hectares connected to the Bogotá River in 1950 to only 1,000 hectares by 2009 (World Bank 2010). In the 1990s, Colombia had no legislation protecting wetlands, and construction companies used marshlands as dump sites for construction debris (often surreptitiously). Companies would fill marshes with debris to both get rid of their waste and to dry the land for new housing. Unstable housing would then be built on precarious land prone to flooding without any oversight. One activist noted, “We watched as bulldozers dumped truckloads of debris, as many as 500 per day. They would dump it and then push it onto the wetland. Every day they would gain space for urbanization.”Footnote 25

Real estate development is closely aligned with political power in Bogotá. For example, Fundación Compartir, the construction company dumping into the Conejera in the early 1990s, was owned by Pedro Gómez Barrero, then the Colombian Ambassador to Venezuela. Even Mayor Gustavo Petro (2014–2015), a known environmentalist, had to maneuver between his environmental principles and his families’ construction companies’ bids around the wetlands, and the fast approvals his family’s projects received from City Hall raised suspicion in the 1990s.Footnote 26 Furthermore, the city’s water utility, Acueducto de Bogotá (EAAB), also contributed to wastewater refuse being dumped in the Conejera and other urban wetlands and did little to prevent dumping by others. Even though Decree 2811 (1974) and Agreement 6 (1990) mandated that a thirty-meter perimeter be erected around rivers and streams, these regulations were flagrantly ignored. Instead, developers frequently purchased land abutting wetlands and requested permits from District Planning to fill areas with rubble, expand lots, and raise soil levels until debris filled and eventually dried the wetland for use in new construction projects.Footnote 27

Civil Society Organizes to Demand Environmental Regulations

Neighbors mobilized to defend the Conejera Wetlands in the early 1990s. While dumping had occurred for years, the completion of a new housing development that abutted the wetlands brought in new residents who would become environmental leaders in their community. The Galindo family, a vast network of siblings and cousins, began to document the flora and fauna in the wetlands and alert their neighbors about the environmental threat. German Galindo noted,

We told them, let’s get organized, this isn’t right, the wetlands have so much potential. More or less what I began to document, I would share with our neighbors—the wetland was, in a way, our backyard garden.Footnote 28

By 1993, the community, led by the Galindo family, had organized its own survey of the Conejera Wetlands and documented both its vast biodiversity and its high levels of pollution, they formed the Conejera Foundation, or FHC (La Fundación Humedal la Conejera) with approximately 15 initial members.Footnote 29

The FHC engaged in multiple acts of resistance against wetlands contamination and lobbied for environmental regulations. First, it warded off the construction company’s dumping by linking arms and forming a human chain when they saw the company’s trucks approaching. Housewives were called to negotiate with the truck drivers, as one leader remembered, “We didn’t think the drivers would go so far as to physically attack a woman.”Footnote 30 The early days included multiple direct actions: activists hid sharp objects in nearby gravel to pop construction trucks’ tires, paid a truck driver to dump trash at the construction company’s office, and even once pulled a weapon out on a truck driver to force him to turn back. City officials were heavily complicit in the wetland’s contamination, and one leader explained, “We had to use all the tools at our disposal to stop the state’s actions… [city leaders] were a group of bandits that didn’t comply with environmental regulations;” even municipal garbage trucks and the Secretariat of Public Works deposited refuse on the wetlands.Footnote 31

The FHC and community partners used litigation and administrative proceedings to fight for diverse environmental projects and regulations surrounding wastewater cleanup in the wetlands. The FHC pressed the Bogotá water utility to build infrastructure that would divert wastewater away from the wetlands; German Galindo intervened directly with the World Bank to assure that wetlands recuperation would be incorporated into the Bank’s wastewater infrastructure investment plans.Footnote 32

The FHC filed a tutela in the Colombian Constitutional Court against the water utility—an injunction claiming that a public agency has committed a violation of constitutional rights. In 1994, the Court ruled in favor of the FHC and demanded that seven institutions across the city treat the wastewater being dumped in the Conejera. In 1997, the FHC filed another administrative proceeding (una acción de desacato) against the water utility for failure to connect over 80,000 residents to wastewater infrastructure and organized a community meeting to publicize the water utility’s negligence. In 1998, the FHC was among fifteen community organizations that sponsored an acción popular, a legal proceeding for violation of collective rights, demanding that the city comply with its obligation to decontaminate the wetlands. A founding member of FHC remembered that in the 1990s, “managing the wetland with public officials was impossible and everything we did was through judges. We implemented forty-eight different judicial processes; it was the only space where we were heard.”Footnote 33 The FHC applied nearly all the constitutional and legal mechanisms for citizen participation available to civil society under Colombia’s 1991 constitution. These included as many as twenty-three different mechanisms, such as the tutela, la acción popular, la acción de nulidad, among many others.Footnote 34 In 1995, the FHC helped create the Bogotá Wetlands Network (Red de Humedales de Bogotá), and worked with Eco Fondo (an environmental NGO fund) to create fifteen different nodes of wetland activism in Bogotá that helped shape city and national wetlands policy.

After numerous legal proceedings, the water utility signed a compliance accord in 2000 and agreed to undertake numerous infrastructure projects to divert wastewater away from the Conejera Wetlands and Bogotá River.Footnote 35 These projects lasted over eight years and included excavating construction debris and installing wastewater connections. By 2008, the many public infrastructure works on the wetlands were finally completed, and residents began to see an explosion of biodiversity in the decontaminated marshland.

Citizen Pressures and Co-creating Subnational Environmental Institutions

Social pressure helped create environmental institutions in Bogotá. Yet unlike the Esteban Echeverría case, social organizations penetrated the state and helped build institutions both from the outside and from within. This more collaborative process was not without conflicts, but the Conejera case featured greater levels of community outreach and education, multiple partnerships with local institutions, and work inside the very institutions they were trying to reform.

Early on, the FHC created educational spaces to raise awareness of the city’s wetlands and support for their preservation. One example was the Ecobus, an educational space promoting native flora and fauna and the merits of wetland preservation. The FHC also brought in police officers and even judges to their workshops in order to inculcate environmental awareness among public officials who were charged with oversight; thousands of residents visited Ecobus, including city officials.Footnote 36 The FHC ran a nonprofit nursery for native species that was financed through DAMA, the Environmental Secretariat; and hundreds of community volunteers planted as many as 42,000 trees and plants into the wetlands and basins of the Bogotá River.Footnote 37 These events gained traction throughout the city as new nodes of activism developed around other urban wetlands and word spread. As one environmental activist not affiliated with the Conejera wetland noted, “The FHC raised me.”Footnote 38

Cross-community collaborations were key. The FHC partnered with universities (e.g., Javeriana in 1998, La Salle in 1997), the Suba municipality’s development office (1998), and Eco Fondos to rehabilitate aquatic systems, produce long-term environmental impact studies, and begin hydrogeomorphic adaptation interventions. The FHC’s institutional curriculum vitae from 2014 lists over thirty-five projects that were co-financed and co-signed between the FHC and multiple state institutions between 1994 to 2012.Footnote 39

Citizen pressures motivated the state to take ownership of the wetlands and dedicate resources to their upkeep. Perhaps most notably, residents and the city teamed up in 2004 to create a district wetlands policy that allowed for institutionalized co-governance; according to one observer it was the “the most participatory environmental blueprint in the country.”Footnote 40 Citizens had a considerable role in the governance of the Conejera wetlands, which linked activists to police officers and other regulatory agents. The city’s secretariat of economic development also worked with the FHC to design an ecotourism business plan in the wetland reserve.Footnote 41

The FHC helped promote wetlands policymaking at every level of government in Colombia, including Colombia’s Ministry of the Environment’s national wetland policy (Resolution 196 in 2006) and national laws No. 356 and 357 for the protection and rational use of wetlands.Footnote 42 By 2018, FHC’s work on multiple fronts led to the Conejera becoming a Ramsar-recognized site.Footnote 43

Retaining citizen influence within the Conejera was full of numerous battles. In 2013, city administrators ordered that the city’s co-administration of the wetlands with activists cease.Footnote 44 The Conejera was declared a District Wetlands Reserve in 2021 (Article 55 of Decree 555), but the formal seat for citizen participation in Conejera oversight was weakened. In addition, some mayors openly attacked conservation efforts. For example, Enrique Peñalosa told the FHC to “go to the Amazon to take care of birds, because the city was for the people,” as he pushed forward his plans for development in the wetlands.”Footnote 45

Notably, FHC founder German Galindo went to work for the Bogotá water utility, EAAB, in 2005. Galindo headed an office that created and implemented regulations for environmental protection. He helped convert environmental protections within the water utility from a low-level initiative to a first-tier office at the top of the public utility’s organizational chart. Galindo helped create an office that oversaw the protection of all the hydraulic systems throughout Bogotá including rivers, waterfalls, wetlands, and páramos. Galindo’s office also created a program of ecological remediation and participatory wetlands management. He noted that “all that we had done in the FHC, we put back to work for the city, and we staffed it, and made it run.”Footnote 46 Within this context, ecological restoration of the city’s wetlands began with the Conejera in 2000 and then spread all across the city. The FHC and the Bogotá water utility signed numerous agreements to complete public works projects. Remarkably, what began as a series of lawsuits became a cooperative collaboration that included activists who went to work in city government.

Building Subnational Environmental Institutions Through Collaborative Strategies

The Conejera activists were so successful in building environmental institutions for wetlands management that they extended into building environmental institutions in the city more broadly. The relatively more collaborative strategies observed in the Bogotá Conejera Wetlands case were due to factors stemming from the biographies of the actors involved and the political openings of the moment. It illustrates several characteristics of the collaborative strategy for co-building subnational environmental institutions. First, outsiders became insiders and helped transform the policy arena from within city government. The Galindo family developed immense technical skill—German Galindo had a degree in veterinary medicine and animal husbandry, and later became an expert on wetlands recuperation. Medardo Galindo acquired a degree in environmental law and led the FHC’s litigation strategies. Pressures came in part from numerous court filings initiated by the FHC, Ramsar’s international spotlight on Bogotá’s wetlands, and national-level conservation laws that the Conejera activists helped pass. Other collaborations—such as with universities—generated hundreds of theses and Ph.D. projects and ultimately knowledge-brokers that helped staff institutions or lobby for further reform. The hundreds of activists and students that engaged with the Conejera as a training ground went on to disseminate technical expertise to help cities reform urban environmental institutions.

Second, Conejera activists encountered more accommodationist governments than organizers in the Rocha case, and their diverse strategies and deep base allowed them to outmaneuver the occasional obstructionist administration. The construction industry in Bogotá was notoriously corrupt and connected to local politicians. Conejera activists used shaming and blaming in the media to expose the illegal dumping by these companies and their connection to political power in the 1990s. Later the wetlands cause benefitted from political openings such as Mayor Gustavo Petro’s leftist/environmental alliances (Eaton 2020, 7–9) that helped create supportive policies for urban water and wastewater that persisted even after Petro left office.Footnote 47 When Mayor Enrique Peñalosa developed his plans to build on the city’s wetlands, Conejera activists stopped new construction through litigation. As one activist recalled, “We just wait them out. They will leave office and we will still be here.”Footnote 48

In this context, Conejera’s mix of both adversarial and collaborative strategies unfolded over time. Conejera activists primarily used litigation, educational forums, and coalition-building with national and international partners. After initial confrontations in the early 1990s, activists did not frequently utilize contentious actions such as mass rallies, marches, or roadblocks. Instead, they invested in institution-building and developed a formidable reputation that opened doors with the state. Because activists penetrated the state from within, the level of collaboration deepened over time through joint projects with the water utility and the city’s environmental office, and through participation on a judicial advisory committee to oversee Bogotá River cleanup after a historic ruling in 2014 (Herrera and Mayka 2020, 6–9).

The Conejera Foundation became the most successful grassroots movement for environmental protections in Bogotá, helping to create environmental institutions and inspiring similar organizations and alliances throughout the country (Palacio 2014). Its achievements were formidable: legal recognition and protection of the Conejera Wetlands, establishing an institutionalized wetlands policy for the city, and earning a space at the policymaking table so that citizens had a voice in wetlands and environmental policy.

Despite their relative successes, co-led environmental regulatory schemes are precarious even when undergirded by strong social movements. For example, when Mayor Enrique Peñalosa’s (2016–2019) attacked protections for the city’s wetlands, FHC-led litigation ultimately succeeded in preserving them, but not before significant development had caused considerable damage. Due to the FHC’s defense of the Thomas Van der Hammen Reserve from Peñalosa’s development plans, the organization’s activists faced character assassination and death threats, causing some to reduce their involvement. Some FHC activities, such as the Ecobus, have been abandoned, but activists continue to lobby for environmental regulations and enforcement.

A new generation of activists—individuals who had participated in Ecobus and other FHC activities—have taken up the mantle by defending wetlands in Suba and forming new organizations such as Tejido Comunitario por el Humedal la Conejera. Jorge Emmanuel Escobar, director of the urban wetlands network Humedales de Bogotá, notes, “We owe much to the Conejera Foundation. It was an iconic movement for Bogotá and perhaps one of the oldest in all of Colombia.”Footnote 49 Subnational environmental institution-building will thus continue in Bogotá with the strong aid of environmental activists. The Bogotá case showcased access to more institutional spaces for sustainable governance of urban wetlands than the Rocha wetlands. Yet, in both cases, subnational environmental institutions are precarious and rely extensively on organized civil society and the ability of activists to adapt over time to meet continual assaults from unregulated urban development.

Conclusion

This article has argued that subnational environmental institutions are often predicated on ongoing pressures from organized civil society. More than a social movement that advocates for discrete policies, new forms of civil society organization are emerging that attempt to hold the state accountable for fulfilling their regulatory obligations. In the cases of urban wetlands governance examined here, residents worked to hold the state accountable for tasks that it was already constitutionally or statutorily assigned but had ignored, such as protecting ecosystems, managing flood zones, and protecting citizens from toxins. This article systematically compared two strategies for citizen-led environmental regulation: adversarial and collaborative strategies, both of which can serve as a regulatory institution of last resort in hostile pro-development urban regimes.

As presented in the Introduction of this special issue, activists in both cases used a broad repertoire of creative strategies to close implementation gaps, both extra-institutional and institutional. In the adversarial strategy of Laguna de Rocha, Greater Buenos Aires, activists remained outsiders whose distance from political power was influenced by the presence of obstructionist governments. They generated a greater number of direct-action strategies such as shaming and blaming via the media, mass marches, and online watchdog groups. In contrast, in Suba, Bogotá, activists eventually transformed direct-action strategies into institution-building across multiple partnerships with universities, government agencies, and other civic organizations. Activists in Suba became insiders, going to work within the very agencies they intended to reform and creating a robust educational training ground for increasing awareness for wetland ecosystems. Both groups used litigation and petitioned institutions at multiple tiers of government, leveraging their expertise while documenting ecological degradation and navigating environmental law. Despite differences in political opportunities, internal membership, and leadership, both groups of activists were able to create protected reserve status for wetlands and focus attention on wetlands as a city’s most important environmental issue. Through this process, activism gave birth to urban environmental institutions in each city.

This article developed the concept of citizen-led environmental regulation through a comparative analysis of Buenos Aires and Bogotá, two cases that illustrated what Arce and Jaskoski (Introduction to Special Issue) term proactive policymaking. In proactive policymaking, civil society actors insert themselves into the policymaking process, and the result is a check on business interests and policymaking content that reflects community needs and greater environmental stewardship. Citizen-led environmental regulation by definition is more proactive, but do differences between colloborative vs adversarial imply that collobarative strategies will necessarily be more effective in boosting regulatory quality?

The Bogotá case had higher levels of regulatory quality if success is measured by the breadth and depth of institutional development, expertise employed, and number of citizens participating in wetlands governance. Yet the Buenos Aires activists faced a considerably higher number of challenges. These included lower political opportunities in terms of unsupportive mayoral and provincial administrations, stronger private sector opponents in the national-level soccer clubs, and a more challenging legal landscape in terms of pre-existing private ownership in the wetlands territory. These challenges shaped the adversarial strategies that were adopted. While both cases began with adversarial strategies, in the Bogotá case a higher number of supportive factors allowed activists to eventually collaborate with state agencies to advance wetland protection goals. While outsiders became insiders in the Bogotá case, activists were prepared to re-engage in litigation and other adverserial strategies if necessary, such as when conditions became disfavorable under the Peñalosa administration. In both cases, adversarial strategies proved to be a necessary component of citizen-led environmental governance, even if only temporarily in the case of Bogotá. Adverserial and direct action strategies are thus not the purview of only reactionary policymaking, as other cases in the special issue suggest, but can also be found in proactive policymaking. The findings from both wetlands cases suggest that higher levels of regulatory quality sometimes requires combative strategies, particularly in weak institutional settings.

The paper’s findings has important implications for understanding subnational environmental governance in Latin America. First, if the threat of social disruption is what gives proactive policymaking “teeth,” we might expect that regulatory institution building, even in the best case scenarios, will require an organized civil society that if necessary, can either take their claims to the street, the media, or the courts. Second, as authority over environmental policy has been decentralized in Latin America to the local level, it matters greatly who gets elected into these newly empowered offices. In Bogotá, Mayor Peñalosa closed doors for environmental activists while Mayor Petro opened them, and in Esteban Echeverría, Mayor Gray first shut down and then supported environmental regulations. Paradoxically, weak local institutions further reinforce the often oversized power that mayors have on environmental governance, but fluid institutions more easily allow for civil society actors to influence local policymaking via direct or indirect channels. Third, participatory institutions—such as the wetlands oversight committees that were formed in both cases—help build out important aspects of environmental regulation, even when they are not permanently imbued with the authority or resources to act. The existence of these institutionalized spaces provide a space for civil society activists to contribute expertise, negotiate for resources, and access information, even if activists are only able to participate under favorable conditions such when there are allies in elected office or after garnering national or international media attention.

The landscape surrounding social mobilization has changed in recent decades in Latin America. New social movements are organizing to demand regulatory moments and institutions, whether in environment, housing, security, or other tasks the state would typically perform. Urban environmental movements showcase this type of mobilization, which is less partisan and ideological than prior movements and rooted in basic demands for clean air, water, and land. Although citizen co-production of environmental regulation is precarious, it is frequently the environmental institution of last resort on a rapidly warming planet.

Notes

The “advisory committee” mechanism has been criticized as limiting the influence of civil society groups due to power imbalances (Dodson 2014, 535).

Rocha wetlands serve multiple ecosystem functions such as flood control, space for repositioning of subterranean waters, water pollution filtering, reduces urban heat, biodiversity reserve, as well as archeological and sociocultural benefits. The Rocha marshes are the most important regulator of creeks that bypass the Matanza River and serve as a “megasponge” that can be the difference between life and death during massive flooding such as the local floods of 2013 (Grupo de Trabajo de Recursos Acuáticos de la Secretaria de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sustentable de la Nación-SAyDS, Anexo II al MEMORANDO COT Nº 33/2010).

Interview with Martin Farina, March 2017. Rocio Magnani, 2012, “Argentina: soja y agrotóxicos entre barrios y casas,” Página 12.

Creaurban SA is an Argentina real estate company which in 2007 was handed to Angelo and Fabio Calcaterra, who added the associate Italian group Ghella. The Calcaterras are cousins to President Macri (2015–2019). After other slated projects stalled, Creaurban SA announced they would develop a warehouse in Monte Grande, which would amount to the industrial use of 122 hectares of the 400 hectares that Angelo Calcaterra owned in the Laguna Rocha territory. The land was affordable and close to the Ezeiza airport. The land was low cost because of its propensity to flood due to its proximity to the wetlands. Once this project was rejected, Calcaterra began growing monocrop soy, which generated the use of a toxic herbicide, glyphosate (Magnani 2012, Biodiversidad). Angelo Calcaterra was owner of the IECSA construction firm.

Creaurbana’s CEO, Angelo Calcaterra had donated to the Kirchners’ presidential campaigns; in 2018, Calcaterra was arrested for paying bribes in a corruption scandal involving kickbacks paid to secure public works projects associated with the Brazilian Odebrecht construction firm. “Two businessmen jailed in ‘notebook’ scandal; Calcaterra seeks plea bargain,” Buenos Aires Times, June 8, 2018.

The resolutions that ceded the land to soccer clubs were Resolutions: 654/2009, 958/2010, and 553/2012.

The Municipal Ordinance was numbered 4627/CD/06, promulgated by Decree 1086 (di Pangracio Undated, 2).

Jésica Bustos and Carla Perelló. 2021. “Historia y resistencia de uno de los 23 humedales del país que está en peligro,” Terraviva. February 2.

“Juan Relmucao, 2014, “El derrotero legal de la laguna,” Agencia Universitaria de Noticias, June 30.

Ibid.

Interview with Martin Farina, March 2017.

Interview with Martin Farina, March 2017; 2009, Foro Ambiental Echeverria Ezeiza (FAEE) Blogspot, “Movilización contra la rezonificación de La Laguna de Rocha,” December 9.

Interview with Martin Farina, March 2017.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

“Exigen protección legal para Laguna de Rocha,” Diario Popular, August 9, 2011.

Interview with Martin Farina, March 2017.

Law 14.488 (B.O 25/2/13) creates the Reserve, based on the terms in Law 10.907 (B.O 6/6//90) of Natural Reserves.

Interview with Martin Farina, Buenos Aires, 201.

Ibid.

Ibid.

“Laguna de Rocha: entre los premios a la calidad, los emprendimientos y los incendios,” El Diario Sur, January 28, 2018.

Colectivo website: http://www.laguna-rocha.com.ar/ on August 25, 2019; March 26, 2019; @Laguna_de_Rocha, August 30, 2019.

Ramsar Sites Information Service, Complejo de Humedales Urbanos del Distrito Capital de Bogotá. Downloaded on March 24, 2022.

Interview with German Galindo, August 2016.

“On Trial: Gustavo Petro.” The Bogota Post. December 14, 2015.

Jhon Barros, “Especial: Así nació el movimiento ciudadano que salvo a los humedales de Bogotá,” Semana, November 11, 2020.

Interview with German Galindo, August 2016.

Jhon Barros, “Especial: Así nació el movimiento ciudadano que salvo a los humedales de Bogotá,” Semana, November 11, 2020.

Interview with German Galindo, August 2016.

Jhon Barros, “Especial: Así nació el movimiento ciudadano que salvo a los humedales de Bogotá,” Semana, November 11, 2020.

Ibid.

Interview with German Galindo, August 2016.

Interview with Medardo Galindo, August 2016.

Jhon Barros, “Especial: Así nació el movimiento ciudadano que salvo a los humedales de Bogotá,” Semana, November 11, 2020.

“El Viejo Bus no es Pasajero.” Sociedad y Cultura, Subase a Suba. 1997. Pp. 5.

“History of Five Wetlands of Bogotá: La Conejera Wetlands.” En Colombia.com. Downloaded on March 3, 2022.

Interview with Alejandro Torres, August 2016.

Hoja de Vida, Fundación Humedal la Conejera, version Jan 2014. These include: Secretaria del Distrital Ambiental, EAAB water utility, Instituto Distrital de Recreación y Deporte, Governorship of Cundinamarca, Instituto de turismo, Botanical Garden, Alcaldía de Bogotá, Alcaldía de Suba, DAMA, among others.

Jhon Barros, “Especial: Así nació el movimiento ciudadano que salvo a los humedales de Bogotá,” Semana, November 11, 2020.

Hoja de Vida, Fundación Humedal la Conejera, version Jan 2014. P. 6.

Ibid, p. 16; Ministerio de Ambiente, Vivienda y Desarrollo Territorial, 2006, Resolución No. 196.

RAMSAR, December 17, 2019.

Ibid p. 5. The Conejera became a “District Ecological Park (Agreement No. 009, 2012).

In Mayor Peñalosa's first administration (1998–2001) he refused to provide resources for wetlands governance. In his second administration (2016–2019) he modified Decree 565 2017, the District Wetlands Policy, in order to greenlight elevated bridges, walking trails and bike paths that would bring more development to the green spaces and that activist opposed. In 2017 A judge ruled that Decree 565 was null, but activists argued that extensive damage had already occurred. Jhon Barros, “Especial: Así nació el movimiento ciudadano que salvo a los humedales de Bogotá,” Semana, November 11, 2020.

Interview with German Galindo, August 2016.

Interview with Susana Muhamed, July 2016.

Interview with Medardo Galindo, August 2016.

References

Abers, Rebecca Neaera, and Margaret E. Keck. 2009. “Mobilizing the State: The Erratic Partner in Brazil’s Participatory Water Policy.” Politics & Society 37 (2): 289–314.

———. 2013. Practical Authority: Agency and Institutional Change in Brazilian Water Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, USA.

Alcañiz, Isabella, and Ricardo A. Gutierrez. 2020. “Between the Global Commodity Boom and Subnational State Capacities: Payment for Environmental Services to Fight Deforestation in Argentina.” Global Environmental Politics 20 (1): 38–59

Amengual, Matthew. 2016. Politicized Enforcement in Argentina: Labor and Environmental Regulation. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Ansell, Christopher, and Alison Gash. 2008. “Collaborative Governance in Theory and Practice.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 18 (4): 543–571.

Berkes, Fikret. 2009. “Evolution of Co-Management: Role of Knowledge Generation, Bridging Organizations and Social Learning.” Journal of Environmental Management 90 (5): 1692–1702.

Birnbaum, Simon. 2016. “Environmental Co-Governance, Legitimacy, and the Quest for Compliance: When and Why Is Stakeholder Participation Desirable?” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 18 (3): 306–323.

Caruso, Sergio. 2021. “Gambeteando La Reserva: Conflictos Ambientales y Urbanización de Humedales. El Caso de Laguna de Rocha (Buenos Aires, Argentina).” Revista Universitaria de Geografía 30 (1): 171–197.

Cooperman, Alicea. 2022. “(Un)Natural Disasters: Electoral Cycles in Disaster Relief.” Comparative Political Studies, 1–40.

Dodson, Giles. 2014. “Co-Governance and Local Empowerment? Conservation Partnership Frameworks and Marine Protection at Mimiwhangata, New Zealand.” Society & Natural Resources 27 (5): 521–539.

Eaton, Kent. 2020. “Bogotá’s Left Turn: Counter-Neoliberalization in Colombia.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research.

Emerson, Kirk, Tina Nabatchi, and Stephen Balogh. 2012. “An Integrative Framework for Collaborative Governance.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 22 (1): 1–29.

Fung, Archon. 2006. “Varieties of Participation in Complex Governance.” Public Administration Review 66: 66–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00667.x.

Gerring, John. “Mere Description.” British Journal of Political Science 42 (04): 721–746. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123412000130.

Herrera, Veronica, and Lindsay Mayka. 2020. “How Do Legal Strategies Advance Social Accountability? Evaluating Mechanisms in Colombia.” Journal of Development Studies 56 (8): 1437–1454.

Hettiarachchi, Missaka, T. H. Morrison, and Clive McAlpine. 2015. “Forty-Three Years of Ramsar and Urban Wetlands.” Global Environmental Change 32: 57–66.

Hettiarachchi, Missaka, Tiffany H. Morrison, and Clive McAlpine. 2019. “Power, Politics and Policy in the Appropriation of Urban Wetlands: The Critical Case of Sri Lanka.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 46 (4): 729–746.

Hochstetler, Kathryn. 2012. “Civil Society and the Regulatory State of the South: A Commentary.” Regulation & Governance 6 (3): 362–370.

Hochstetler, Kathryn, and Margaret E Keck. 2007. Greening Brazil : Environmental Activism in State and Society. Durham: Durham : Duke University Press.

Kopas, Jacob, Jorge Mangonnet, and Johannes Urpelainen. 2021. “Playing Politics with Environmental Protection: The Political Economy of Designating Protected Areas.” Journal of Politics.

Lemos, Maria Carmen, and Arun Agrawal. 2006. “Environmental Governance.” Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 31: 297–325.

Levitsky, Steven, and María Victoria Murillo. 2009. “Variation in Institutional Strength.” Annual Review of Political Science 12 (1): 115–133.

Madariaga, Aldo, Antoine Maillet, and Joaquín Rozas. 2021. “Multilevel Business Power in Environmental Politics: The Avocado Boom and Water Scarcity in Chile.” Environmental Politics 30 (7): 1174–1195.

Milmanda, Belen, and Candelaria Garay. 2020. “The Multilevel Politics of Enforcement: Environmental Institutions in Argentina.” Politics & Society.

Mintah, Frank, Clifford Amoako, and Kwasi Kwafo Adarkwa. 2021. “The Fate of Urban Wetlands in Kumasi: An Analysis of Customary Governance and Spatio-Temporal Changes.” Land Use Policy 111: 105787.

O’Rourke, Dara. 2002. “Community-Driven Regulation: Toward an Improved Model of Environmental Regulation in Vietnam.” In Livable Cities? Urban Struggles for Livelihood and Sustainability, edited by Peter Evans. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Ostrom, Elinor. 1996. “Crossing the Great Divide: Coproduction, Synergy, and Development.” World Development 24 (6): 1073–1087.

Palacio, Dolly Cristiana. 2014. Dinámicas de Participación En La Formación de Lugares-Patrimonio: Humedales y Centro Histórico En Bogotá. Bienes, Paisajes e Itinerarios 85 (April): 78–99.

Pangracio, Ana di. Undated. “Laguna de Rocha: Una Reserva Natural Desprotegida.” FARN.

Pasotti, Eleonora. 2020. Resisting Redevelopment: Protest in Aspiring Global Cities. New York, N.Y: Cambridge University Press.

Plummer, Ryan, and Derek Armitage. 2007. Crossing Boundaries, Crossing Scales: The Evolution of Environment and Resource Co-Management. Geography Compass 1 (4): 834–849.

Urkidi, Leire, and Mariana Walter. 2011. “Dimensions of Environmental Justice in Anti-Gold Mining Movements in Latin America.” Geoforum 42 (6): 683–695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2011.06.003.

World Bank. 2010. “Informe No. 54311-CO: Proyecto de Adecuación Hidráulica y Recuperación Ambiental Del Río Bogotá.” World Bank.

Acknowledgements

The author appreciates the helpful feedback from Moises Arce and Maiah Jaskoski, participants in the REPAL 2023 Conference in Quito, Ecuador, and Lindsay Mayka and Megan Mullin. Diana Alcocer and Stephanie Andrade provided invaluable research assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection: Special Issue on Subnational Environmental Governance Institutions in Latin America

Appendix

Appendix

Interview List

Buenos Aires, Argentina.

-

1.

Leandro Vera Belli, Centro de Estudios Legales y Sociales (CELS), Member of Cuerpo Colegiado, March 2016

-

2.

Andres Napoli, Fundación Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (FARN), Member of Cuerpo Colegiado, March 2016

-

3.

Alfredo Alberto, Asociación de Vecinos de la Boca, Member of Cuerpo Colegiado, March 2016

-

4.

Eduardo Reese, Centro de Estudios Legales y Sociales (CELS), Member of Cuerpo Colegiado, March 2016

-

5.

Gabriela Merlinksy, Area de Estudios Urbanos del Instituto Gino Germani, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Academic and Expert, April 2016

-

6.

Melina Tobias, Expert, Centro de Estudios Legales y Sociales (CELS), Academic and Expert, April 2016

-

7.

Ricardo Gutierrez, Universidad Nacional San Martin, Academic and Expert, April 2016

-

8.

Cristina Fins, Asociación de Vecinos de la Boca, Member of Cuerpo Colegiado, March 2016

-

9.

Diego Morales, Centro de Estudios Legales y Sociales (CELS), Member of Cuerpo Colegiado, Attorney, March 2016

-

10.

Marina Aizen, Clarin, Journalist, April 2016

-

11.

Leonel Mingo, Employee, Greenpeace Argentina, Member of Cuerpo Colegiado, April 2016

-

12.

Leandro Garcia Silva, Defensor del Pueblo de la Nación, Attorney, April 2016

-

13.

Javier Garcia Espil, Defensor del Pueblo de la Nación, Attorney, April 2016

-

14.

Horacio Esber, Attorney, Defensor del Pueblo de la Nación, April 2016

-

15.

Antolin Magallanes, Director, ACUMAR, April 2016

-

16.

Andres Napoli, Subdirector, Fundación Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (FARN), April 2016

-

17.

Sergio Federovisky, Board of Directors, ACUMAR, April 2016

-

18.

Lorena Suarez, Employee, ACUMAR, April 2016

-

19.

Maximo Lanzetta, Municipalidad de Almirante Brown, Secretaria de Medio Ambiente, April 2016

-

20.

Carolina Ciancio, Activist, Asociación Ciudadana de Derechos Humanos (ACDH), Member of Cuerpo Colegiado, April 2016.

-

21.

Lorena Pujo, Greenpeace Argentina, Member of Cuerpo Colegiado, April 2016

-

22.

Leandro Garcia Silvia, Attorney, Defensor del Pueblo de la Nación, March 2017

-

23.

Luis Armella, Juez Federal de Quilmes, March 2017

-

24.

Andres Napoli, Subdirector, Fundación Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (FARN), Member of Cuerpo Colegiado, March 2017

-

25.

Carolina Farnstein, Attorney, Centro de Estudios Legales y Sociales (CELS), Member of Cuerpo Colegiado, March 2017

-

26.

Enrique Viales, March 2017

-

27.

Laura Rocha, Journalist, La Nacion, March 2017

-

28.

Patricia Rodrgiuez, Activist, Organización Ambiental Pilmayqueñ, March 2017

-

29.

Martin Farina, Activist, Colectivo Ecologica Unidos por la Laguna de Rocha, March 2017

-

30.

Barbara Moramarco, Attorney, Secretario 8, Juzgado de Moron, March 2017

-

31.

Ignacio Calvi, Secretario 8, Juzgado de Moron, March 2017

-

32.

Nestor Cafferatta, Secretario de Juicio Ambientales, Corte Suprema de Justicia de la Nacion, March 2017

Bogotá, Colombia.

-

1.

Tatiano Pardo, El Tiempo, Journalist, July 2016

-

2.

Lucila Reyes, Manager, Secretaria Distrital del Ambiente, Dirección Jurídica, Ciudad de Bogotá, July 2016

-

3.

Freddy Franco, Expert, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Sede Manizales, July 2016

-

4.

Medardo Galindo, Activist, Fundación Humedal de la Conejera, July 2016

-

5.

Luis Jorge Vargas, Activist, Fundación Humedal de la Conejera, July 2016

-

6.

Alvaro Sanchez, Employee, Dirección Desarrollo Regional, Secretaria de Planeación de Cundinamarca, July 2016

-

7.

Roberto Gonzalez, Director, Desarrollo Regional Gobernación de Cundinamarca, July 2016

-

8.

Sandra Sguerra, Director, Secretaria Distrital del Ambiente, Dirección Jurídica, Ciudad de Bogotá, July 2016

-

9.

Alvaro Carillo, Personal Assistant to City Council Person, Concejo de Bogotá, Partido Liberal, August 2016

-

10.

Susana Muhamed, Minister, Secretaria del Medio Ambiente, Bogotá, August 2016

-

11.

Alberto Groot, Empresa de Acueducto, Alcantarillado y Aseo de Bogotá, E.S.P. (EAAB), August 2016

-

12.

Marco Antonio Velilla Moreno, Consejo del Estado, High Court Justice, August 2016

-

13.