Abstract

Individuals who access residential treatment for substance use disorders are at a greater risk of negative health and substance-use outcomes upon exiting treatment. Using linked data, we aimed to identify predictive factors and the critical period for alcohol or other drug (AOD)-related events following discharge. Participants include 1056 individuals admitted to three residential treatment centres in Queensland, Australia from January 1 2014 to December 31 2016. We linked participants’ treatment data with administrative data from hospitals, emergency departments, AOD services, mental health services and the death registry up to December 31 2018. We used survival analysis to examine presentations for AOD-related events within two-years of index discharge. A high proportion of individuals (57%) presented to healthcare services for AOD-related events within 2 year of discharge from residential treatment, with the first 30 days representing a critical period of increased risk. Completing residential treatment (aHR = 0.49 [0.37–0.66], p < .001) and high drug-abstaining self-efficacy (aHR = 0.60 [0.44–0.82], p = .001) were associated with a reduced likelihood of AOD-related events. Individuals with over two previous residential treatment admissions (aHR = 1.31 [1.04–1.64], p = .029), identifying as Indigenous Australian (aHR = 1.34 [1.10–1.63], p < .001), alcohol as a primary substance (aHR = 1.58 [1.30–1.92], p < .001), and receiving a Disability Support Pension (aHR = 1.48 [1.06–2.06], p = 0.022) were at a greater likelihood. The high proportion of individuals that present to health and drug services for AOD-related events, especially in the first 30 days post-discharge, highlights the need for continued support following discharge from substance use treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Residential substance use treatment targets the substance use and overall functioning of individuals with moderate to severe substance use disorders (SUDs) (United States. Department of Health and Human Services, 2016). These centres utilise various models such as therapeutic communites; structured drug-free settings focused on fostering client-led support and re-entry to community following exit from treatment (Goethals et al., 2011). Despite being a common model, therapeutic communities can vary in length, treatment modalities, professional supoport, and treatment goals, leading to hetereogeneity across therapeutic community programs and outcomes (Vanderplasschen et al., 2013). Individuals attending these services see improvements in higher rates of abstinence (McKetin et al., 2018), and reduced rates of overdose, substance use frequency and relapse (Andersson et al., 2019; Pasareanu et al., 2016). However, it is also important to consider healthcare service use outside of residential treatment.

Individuals with SUDs are known to utilise healthcare services at a higher rate than the general population, with higher rates of preventable hospital readmissions and recurrent hospital utilisation compared to other health disorders (Ahmedani et al., 2015; Mark et al., 2013; van Walraven et al., 2011; van Walraven et al., 2012; Vu et al., 2015; Walley et al., 2012). A systematic review and meta-analysis of health-care services, including hospitals, primary care and emergency departments (EDs), estimated that individuals who use illicit drugs utilise these services at a rate seven times higher than the general population (Lewer et al., 2020), with a more recent meta-analysis estimating the global prevalence of acute care utilisation among individuals with substance-related disorders to be 36% for ED visits and 41% for hospitalisations (Armoon et al., 2023). Additionally, those with SUDs frequently utilise mental health services (Wang et al., 2007), particularly if they have co-morbid anxiety and mood disorders, methamphetamine use or injection drug use (Duncan et al., 2022; McKetin et al., 2018). Such frequent utilisation of healthcare services is both costly and indicative of poorer outcomes (Davies et al., 2017), yet there is currently a lack of research with reliable outcome data for individuals who have attended residential treatment services for substance use.

Research investigating residential treatment is primarily self-report and largely contains no follow-up data post-discharge from treatment. Additionally, these studies often have biased treatment evaluations due to the attrition of participants with poorer in-treatment outcomes (Cutcliffe et al., 2016; de Andrade et al., 2019; Gray & Argaez, 2019; Reif et al., 2014; Vanderplasschen et al., 2013). Due to challenges encountered when following up individuals who have accessed residential treatment, one method of collecting substance use information post treatment is administrative data linkage. Using administrative data collected across these highly utilised services can provide valuable information on individuals’ substance use following separation from drug treatment.

Data linkage has emerged as a valuable alternative method of data collection that utilizes existing administrative data infrastructure to obtain longitudinal data, particularly for hard-to-reach populations (Brownell & Jutte, 2013; Willey et al., 2016). Despite its potential, few studies have employed data linkage as a statistical method to investigate outcomes of residential treatment for substance use. In a retrospective data-linkage study comparing mortality outcomes of different treatment modalities for individuals with SUDs in Australia, residential treatment was associated with the highest risk of premature death in the first-year post-discharge—possibly related to the severity of dependence (Lloyd et al., 2017). This was similarly found in a study by Tisdale et al. (2021) linking residential treatment data with the Registry of Deaths, wherein individuals attending residential treatment in Australia were almost four times as likely to experience premature death following discharge when compared to the general population.

Maughan and Becker (2019) similarly found that drug-related mortality was highest in the first 4 weeks following SUD treatment, with individuals discharging from residential treatment at substantially higher risk of mortality than other treatment modalities. Higher mortality risks following residential treatment have been linked to the severity of dependence (Lloyd et al., 2017) and observed among individuals primarily using alcohol and opioids (Maughan & Becker, 2019); however, further research investigating the factors influencing these deaths in the period following treatment is needed. Most premature deaths observed in these studies pertained to AOD-related suicide and overdose; collectively highlighting a critical period of increased risk following discharge from residential treatment.

Within other health settings, data linkage has been used to investigate individuals with SUDs to identify and quantify risk factors associated with higher rehospitalisation (Nordeck et al., 2018), SUD treatment completion (Smith, 2020) and overdose rates (Krawczyk et al., 2020). The idea of a critical period of increased risk for vulnerable populations following separation from services is seen in other high-risk populations. Among individuals who experience incarceration in Australia, Keen et al. (2020) found that non-fatal overdoses were highest 14 days following release from prison, highlighting a lack of transitional care from service to community. In a study investigating risks of mortality, the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs health system conducted a linkage study in which inpatient mental health units were linked with the National Death Index. The study found elevated rates of non-suicidal mortality within the first 30 to 90 days from discharge, specifying patients with dementia and neurodegenerative disease as high-risk intervention targets (Katz et al., 2019). These studies demonstrate the potential of data linkage to identify critical periods of risk for vulnerable populations and develop targeted interventions to reduce the risk of negative outcomes following separation from treatment services. The use of administrative data across healthcare services can provide valuable information on individuals’ substance use following separation from drug treatment and offers intervention opportunities to improve outcomes.

Currently, there is a significant lack of research investigating the outcomes of residential treatment following discharge. Individuals with SUDs have a higher likelihood of premature death and are frequent users of health services such as hospitals, EDs and mental health services. Given the high utilisation of these services and premature death, it is possible to leverage administrative data collected during presentations to these services and following death to investigate substance use outcomes following separation from residential treatment. Using administrative data linkage from AOD treatment (ATODS), mental health facilities (CIMHA), emergency departments (ED), hospital settings (QHAPDC), as well as deaths recorded with the Registry of Deaths, we aim to examine alcohol and other drug (AOD)-related events that result in utilisation of health services or death following separation from residential substance use treatment. Specifically, we aim to (1) describe the frequencies of AOD-related events across these services and to quantify the first AOD-related service contact following discharge; (2) identify the critical period of time when individuals with SUDs are at the highest risk of first presenting to a health service for an AOD-related event following discharge from residential treatment; and (3) determine patient characteristics that predict AOD-related health service utilisation during the two-year period following discharge from to residential treatment.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Base Cohort–Residential Substance Use Treatment Services

Participants include 1056 individuals admitted to one of three residential substances use treatment centres for moderate to severe SUDs from January 1, 2014 to December 31, 2016 in Queensland, Australia. The organisation operating the residential services is a non-for-profit government funded AOD service provider in Queensland and New South Wales, Australia, with both inpatient and outpatient services. Inpatient services were government subsidised; accepting welfare-pension based stays from self-, professional- and court-mandated referrals. A therapeutic community model of care was used at these centres during the treatment period focusing on community-led roles (e.g. scheduling, cleaning, cooking) and included client- and professional-led aspects such as group therapy, workshops and education. These services required detoxification at admission and applied no smoking and/or drug policies. At the time of data collection, three residential services were operated including a site for young adults (18–25), adults (25+) and an Indigenous Australian exclusive site. Data for participants was inclusive of 2 years from final discharge at one of these residential treatment centres. Episode data was deidentified and extracted by a reporting analyst from the service provider.

Measures

Alcohol or Other Drug-Related Event

The outcome is an ‘alcohol and other drug-related event’ (AOD-related event) within 2 years of discharge from residential treatment, created by linking several datasets (QHAPDC, CIMHA, ATODS, EDIS, Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages; see Table 1) to indicate a service presentation or death that was partially or fully due to substance use. International Classification of Disease 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes were primarily used to identify presentations attributable to substance use (wholly or partially; see Appendix 1 Table 4 and Appendix 2 Table 5 for lists).

Time from Discharge

The number of days from discharge from residential treatment was used to measure the length of time until an event occurs, censored at 2 years. Individuals were censored if premature death occurred.

Predictor Variables

The residential treatment database provided data on the cohort’s demographic characteristics, treatment history, substance use, mental health and drug-abstaining self-efficacy.

Demographics

Demographic characteristics were age (under 25 years/over 25 years), sex (female/male), legal status (justice involved at admission yes/no), Indigenous Australian status (yes/no; included Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander origin).

Treatment

Treatment data were the number of previous admissions (no/1/2+ previous admissions) and treatment completion (treatment completed/early discharge). A successful treatment completion was recorded by staff if a participant spent a minimum of 4 weeks within a residential substance use facility and demonstrated progress towards treatment goals with a planned exit or transition out of treatment.

Substance Use

The primary substance of concern identified by clients at admission from a list of 22 substances was recoded into four categories, including alcohol, cannabis and methamphetamine or ‘other’ drugs which included substances with low frequency (e.g. heroin, cocaine, opioids). Lifetime injecting drug use status was a binary variable (no/yes). Polysubstance use was recoded into a binary variable for individuals with three or more substances of concern (no/yes).

Mental Health

The 21-item Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21) (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995) assessed mental health in the week prior to admission. The DASS-21 measures depression, anxiety and stress through a four-point Likert scale, where scores range from 0 ‘did not apply to me at all’ to 3 ‘applied to me very much or most of the time’. We used a total score across the DASS-21 to create a composite measure of general mental health and transformed scores into z-scores to standardize. The DASS has been established in substance-using populations (Beaufort et al., 2017) and has demonstrated excellent reliability (Depression: α = 0.81, Anxiety: α = 0.89, Stress: α = 0.78), concurrent validity, convergent validity, internal validity and discriminative validity (Coker et al., 2018).

Drug Refusal Self-Efficacy

The Drug Taking Confidence Questionnaire (DTCQ-8) provides an assessment of drug refusal self-efficacy through eight items that represent high-risk scenarios for substance use (Sklar & Turner, 1999). Participants indicate their level of confidence in resisting the urge to drink excessively or use drugs on a 6-point scale, which ranges from 0% (not at all confident) to 100% (very confident). Scores less than 80% are categorized as low drug-abstaining self-efficacy, while scores of 80% or higher are categorized as high drug-abstaining self-efficacy. The reliability (α = 0.889) and validity of the DTCQ-8 has been established in substance-using populations (Vasconcelos et al., 2016).

Ethics Approval

This study was approved by the University of Queensland Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number: 2018001063) which includes written approval from the AOD-service and Queensland Health Statistical Services Branch.

Statistical Analysis

Missing data was highest for the DTCQ-8 (6.0%) and DASS-21 (4.6%) at admission. Multivariate imputation by chained equations through SPSS statistical software was used to impute missing data (Jakobsen et al., 2017), and the multiple imputed and original data were similar overall (see Appendix 3: Table 6).

A descriptive analysis of the cohort was conducted. Chi-square and t tests were used to compare the proportion with an AOD-related event by participant characteristics. Cox-regression survival analysis was used to investigate the risk of an AOD-related event and to estimate the time until an AOD-related event occurred. Analyses controlled for all covariates. Follow-up was censored at 2 years (731 days) from index discharge from residential treatment to a maximum date of 31 December 2018. We used SPSS statistical software to conduct all analyses, and RStudio for plots. Unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios were computed with 95% confidence intervals.

Results

Participants Characteristics

Participants were primarily male (n = 695, 65.8%) with a mean age of 32 years (M = 32.06, SD = 9.55), 26.6% (n = 281) identified as Indigenous Australian. Most had alcohol (n = 403, 38.1%) or methamphetamine (n = 407, 38.5%) as their primary substance of concern (Table 2).

Presentation for an AOD-Related Event Following Residential Treatment Discharge

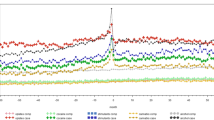

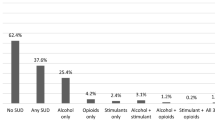

A total of 600 (56.8%) participants presented for an AOD-related event within 2 years of discharge from residential treatment. At 30 days post-discharge, 136 (12.9%) participants had presented, increasing to 325 (30.8%) by 6 months, 444 (42.0%) by 1 year and 600 (56.8%) by 2 years. The most hazardous period for AOD-related events was the first month, as indicated by the steepest part of the survival curve (Fig. 1). Within 2 years of discharge, 42% of individuals presented to an ED, 42% to a hospital, 32% to a drug service provider, 20% to a mental health service and 2% experienced an AOD-related death.

Socio-Demographic and Individual Characteristic Correlates

Those who presented for an AOD-related event were more likely to be aged over 25 years old (n = 478, 58.9%), did not complete treatment (n = 541, 59.8%) and had low drug-abstaining self-efficacy (n = 663, 62.8%).

For those that presented to a health service in the 2 year follow-up, the mean number of days to an AOD-related event was 447.46 days (SD = 300.60, 95CI: 429.33–465.59). Time to AOD-related event is shown in Fig. 1. The cox regression model demonstrated that after adjusting for all other factors, completing treatment at a residential service (aHR = 0.49 [0.37–0.66], p < .001) and high drug-abstaining self-efficacy at admission, as measured by the DTCQ-8 (aHR = 0.60 [0.44–0.82, p = .001) were significantly associated with a reduced likelihood of an AOD-related service presentation following discharge (Table 3 and Figs. 2, 3, 4, and 5).

Individuals with alcohol as their primary substance of concern (aHR = 1.58 [1.30–1.92], p < .001), received a Disability Support Pension (aHR = 1.48 [1.06–2.06], p = 0.022), and had two or more previous admissions to residential treatment (aHR = 1.31 [1.04–1.64], p = .022) were at a greater risk of presenting for AOD-related events. Individuals who identified as Indigenous Australian were at a significantly greater risk of presentation for an AOD-related event (aHR = 1.34 [1.10–1.63], p < .001). Scoring higher on the DASS-21 (aHR = 0.62 [0.45–0.84], p = 0.010) was significantly associated with a reduced likelihood of presentation.

Discussion

To understand outcomes after leaving residential treatment for SUDs, we linked data from hospitals, EDs, mental health services and AOD services to examine subsequent AOD-related events. A high proportion of individuals presented for an AOD-related event (56.8%) within the 2-year period following discharge. Residential treatment completion and high drug-abstaining self-efficacy were protective factors, while two or more previous admissions and Indigenous Australian status were risk factors for such events. Identifying the risk factors of accessing health services for AOD-related events has significant implications for the development and delivery of AOD treatment programs and policies.

Previous research has identified the first six months following discharge as a period of increased risk of death, readmission, relapse, injecting behaviour and hospitalisations (Bockmann et al., 2019; Nordeck et al., 2018; Yedlapati & Stewart, 2018). Our study suggests the first month following discharge represents an acute period of increased risk for problematic substance use as measured by greater risks of readmission, relapse, hospitalisation and premature death. This critical period of risk has been observed in other high-risk populations such as individuals separating from prisons, mental health services and hospitals (Katz et al., 2019; Keen et al., 2020; Nordeck et al., 2018). This critical period represents an opportunity to provide targeted support through high-risk transitional periods following discharge from residential treatment. Intervening during these key periods may reduce the poorer substance use outcomes that occur during this first month. Inter-service communication following the pathways of clients as they access subsequent services may support the health journey of other individuals with similar presenting problems.

Individuals that completed treatment at a residential substance use treatment service were half as likely to access a health service for an AOD-related event than individuals who discharged early from treatment. While previous research has evidenced completing residential treatment to improve substance use, treatment and health outcomes following treatment (Drake et al., 2012; McKetin et al., 2018; Pasareanu et al., 2016), these studies are often limited by poor follow-up (Cutcliffe et al., 2016; de Andrade et al., 2019; Gray & Argaez, 2019; Reif et al., 2014; Vanderplasschen et al., 2013). As individuals with unmet substance use treatment require greater hospital and ED utilisation than individuals with adequate treatment (Rockett et al., 2005), completing treatment may act as a protective factor against adverse AOD-related events. While there is support for the effectiveness of long-term (> 90 days) residential treatment in the reduction of relapse (Andersson et al., 2019), these findings contribute to the literature that residential treatment can have a significant impact on relapse with just 4 weeks of successful treatment (de Andrade et al., 2019; Mohamed et al., 2022).

We found individuals with high drug-abstaining self-efficacy were less likely to have an AOD-related event. As seen in previous research, drug-abstaining self-efficacy is a strong predictor of 1-year abstinence following residential treatment for substance use disorders (Ilgen et al., 2005), and has been found to predict abstinence and drinking frequency 5 years post treatment (Muller et al., 2019). Our findings add to the literature that drug-abstaining self-efficacy results in lower likelihood of substance use events up to 2 years following discharge and informs future research investigating the application of treatments aiming to improve drug-abstaining self-efficacy.

Indigenous Australians are impacted by AOD-related health problems at a far greater rate than non-Indigenous Australians (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2018; Wynne-Jones et al., 2016). These risks extend to increased health service utilisation, experiencing greater rates of substance use treatment, hospitalisations and premature AOD-related deaths up to 5-times higher than the non-Indigenous Australian population (Al-Yaman, 2017; Nathan et al., 2020). This increased health service utilisation is due to a range of complex factors, including historical and ongoing discrimination, socioeconomic disadvantage, cultural barriers and limited access to appropriate health care services which is beyond what is captured in the current study. It is essential to develop and provide access to culturally appropriate prevention and treatment services that are designed in collaboration with Indigenous communities.

Recurrent admissions to a residential treatment service have been associated with poorer treatment and substance use outcomes following discharge from treatment (Decker et al., 2017). In the current study, individuals who admitted to two or more previous episodes were more likely to access a health service for AOD-related events. By integrating substance use intervention into healthcare episodes that indicate a return to substance use, healthcare providers can help to identify and address substance use behaviours, reducing the risk of progression and improving overall health outcomes for patients.

Attending a residential service with alcohol as the primary drug of concern was associated with a higher risk of presenting with an AOD-related event following discharge. There is a demonstrated relationship between alcohol use and increased presentations to hospitals, EDs, mental health services and death (Armoon et al., 2021; Iranpour & Nakhaee, 2019; Leung et al., 2023; Zarkin et al., 2004). Individuals who primarily use alcohol are at a greater risk of experiencing somatic health concerns, often experience greater premature mortality (Hjemsaeter et al., 2019), and are more likely to be admitted for trauma related injuries than other substance users (cocaine, heroin, cannabis) (Weintraub et al., 2001). Due to the high utilisation of hospitals and EDs attributable to alcohol use, these service contacts present missed opportunities to offer substance use support aimed at reducing the poorer health outcomes associated with alcohol use.

Individuals receiving a government DSP at admission to treatment were at a greater likelihood of AOD-related events than those not receiving a governmental pension. Receiving the DSP in Australia has been associated with poorer income-related circumstances (poverty, housing insecurity, unemployment), social factors (stigma) and health factors such as declining mental health compared to those who do not receive a pension (Kavanagh, 2020; Kavanagh et al., 2013; Kavanagh et al., 2015; Krnjacki et al., 2018; Milner et al., 2020), exacerbating the myriad risks experienced by individuals living with disabilities. These health disparities and poorer outcomes are particularly of concern when compounded with substance use, demonstrated by the high likelihood of those receiving the DSP to present to health services for AOD-related events following residential treatment. Greater continuing and aftercare is needed for those living with disabilities seeking AOD treatment to address and mitigate the heightened disadvantage experienced by this sub-population.

Previous literature has shown that individuals with co-occurring mental health concerns have worse substance use outcomes, higher rates of hospitalisations and a greater likelihood of early discharge from treatment (Gomez-Sanchez-Lafuente et al., 2022; McGovern et al., 2014; Sofer et al., 2018; Sofin et al., 2017), which we did not find. These potentially spurious findings may have occurred due to incomplete or inaccurate data, a limitation of administrative data linkage. Admission DASS-21 scores measured the cohort as having lower mental health concern than previous estimates in Australia of 47–100% (Kingston et al., 2017) with severe and extremely severe scores on depression (34.6%), anxiety (37.5%) and stress (27.5%) being below this estimate.

Improving measurement in low-resource environments such as residential treatments can be challenging due to the burden on staff. However, implementing low-burden measurement strategies into care such as routine outcome monitoring (Carlier & Van Eeden, 2017; Lambert et al., 2018; Neale et al., 2016), is important to assess and improve treatment outcomes while ensuring data is being collected accurately and consistently.

Strengths

This is one of the first studies to use data linkage to follow-up individuals accessing residential substance use treatment. Follow up of individuals following residential treatment is difficult and outcomes are often hard to track due to the hard-to-reach nature of participants; usually the result of significant social, health and economic disadvantages among this population such as unemployment, homelessness, hospitalisation and criminal justice involvement. In the current study, we were able to avoid the typical rates of high attrition by tracking individuals through administrative data of multiple services. Using multi-service administrative data to develop an objective measure of substance use, we were able to examine the outcomes of residential treatment and examine protective and risk factors associated with substance use following residential treatment. Linking multiple health services such as EDs and hospitals improved the quality of data within the current study; by reducing errors, identifying duplications, and improving accuracy between service data. These findings highlight key intervention opportunities for continued care following separation from residential treatment services, with the potential to improve substance use outcomes.

Limitations

As this was one of the first studies to utilise data linkage to investigate individuals who access residential treatment, a relatively small number of participants were included in the 2 years of inclusion. As a result, measures were recoded into categorical variables to increase power and avoid risk of reidentification, leading to a loss in specificity. All participants were included from only one alcohol and drug inpatient service provider across three locations: representing only one model of residential care and limiting the generalisability of findings. Data linkage investigates retrospective cohort data through clinical service records which by the nature of administrative systems require years to process and obtain. The current study collected residential data from ~ 7 to 9 years ago and linked administrative data from ~ 7 to 5 years. Improving current health information systems to deliver this data more rapidly to treatment services, government reporting institutes, and researchers could improve the understanding of health outcomes for vulnerable populations who frequent these services.

Despite these limitations, this is one of the first studies to demonstrate the application of administrative data linkage to this population, with findings that remain pertinent to future research, and current drug treatment and health systems. Future research should expand the inclusion period and include multiple AOD inpatient services to extend the sample size and generalisability of these findings. Capturing information regarding the time prior to residential treatment admission may provide a greater understanding of substance use patterns that lead to seeking residential treatment. Similarly, improving measurement and examination of within-treatment factors (treatment readiness and engagement, adjustment to daily routine, social relationship interruption) and continuing-care services could address how treatment transition processes impact post-treatment outcomes, especially during the first month.

We were not able to access ambulance data in the current study. Ambulatory datasets routinely capture substance use information with greater specificity than is routinely collected in other population-level datasets such as hospitals and EDs (Lubman et al., 2020). Previous research has identified that one in four ambulance service presentations are transferred and recorded in EDs in Australia (AIHW, 2018). However, when specifically estimating AOD-related ambulatory attendances in Australia, over 70% of attendances are transported to an ED (Ferris et al., 2016), indicating that the majority of AOD-related ambulatory episodes were likely to have been captured in the current study. We only quantified AOD-related events that resulted in service utilisation however many individuals may return to AOD use without the need for health service contact. Thus, our study is not a true representation of relapse following residential discharge, only a return to problematic AOD-use resulting in service utilisation.

Research implementing low burden digital data collection methods such as routine outcome monitoring (ROM) could navigate the time delays and data quality limitations observed in this study (Beck et al., 2021; Carlier & Van Eeden, 2017; Lambert et al., 2018). Future research leveraging ROM in tandem with data linkage could enable the delivery of post-treatment outcome evaluation with increased efficiency and quality while simultaneously aiming to improve these outcomes.

Conclusion

By utilising data linkage to develop a measure of substance use following residential treatment, this study provides novel insights into the period directly following treatment exit, a period typically difficult to measure. The first month after leaving residential treatment for substance use disorders is a critical period with the greatest risk of problematic substance use leading to health service utilisation and premature death. This finding has important implications for clinical practice and highlights the potential benefits of incorporating continuing care into treatment plans for individuals with substance use disorders, especially during presentations to health services. By providing ongoing support and monitoring, continuing care can help individuals maintain treatment gains and prevent relapse, thereby reducing the risk of future hospitalizations and ED visits. Future research should expand the use of data linkage in tandem with current outcome measurement methodology to examine and triangulate post-treatment outcomes. Furthermore, examination of the specific components and optimal duration of continuing care that are most effective in reducing the need for acute care among individuals with substance use disorders is needed. Overall, the findings suggest potential intervention targets and highlight continuing care as a crucial component of a comprehensive approach to treating substance use disorders and promoting long-term recovery.

References

Ahmedani, B. K., Solberg, L. I., Copeland, L. A., Fang-Hollingsworth, Y., Stewart, C., Hu, J., Nerenz, D. R., Williams, L. K., Cassidy-Bushrow, A. E., Waxmonsky, J., Lu, C. Y., Waitzfelder, B. E., Owen-Smith, A. A., Coleman, K. J., Lynch, F. L., Ahmed, A. T., Beck, A., Rossom, R. C., & Simon, G. E. (2015). Psychiatric comorbidity and 30-day readmissions after hospitalization for heart failure, AMI, and pneumonia. Psychiatric Services, 66(2), 134–140. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201300518

Al-Yaman, F. (2017). The Australian Burden of Disease Study: impact and causes of illness and death in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, 2011. Public Health Research & Practice, 27(4). https://doi.org/10.17061/phrp2741732

Andersson, H. W., Wenaas, M., & Nordfjaern, T. (2019). Relapse after inpatient substance use treatment: A prospective cohort study among users of illicit substances. Addictive Behaviors, 90, 222–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.11.008

Armoon, B., Grenier, G., Cao, Z. R., Huynh, C., & Fleury, M. J. (2021). Frequencies of emergency department use and hospitalization comparing patients with different types of substance or polysubstance-related disorders. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 16(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-021-00421-7

Armoon, B., Griffiths, M. D., Mohammadi, R., Ahounbar, E., & Fleury, M.-J. (2023). Acute care utilization and its associated determinants among patients with substance-related disorders: A worldwide systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 00, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12936

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2018). Alcohol, tobacco & other drugs in Australia 2018. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/alcohol/alcohol-tobacco-other-drugs-australia/contents/priority-populations/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-people. Accessed May 2023

Beaufort, I. N., De Weert-Van Oene, G. H., Buwalda, V. A. J., de Leeuw, J. R. J., & Goudriaan, A. E. (2017). The depression, anxiety and stress scale (DASS-21) as a screener for depression in substance use disorder inpatients: A pilot study. European Addiction Research, 23(5), 260–268. https://doi.org/10.1159/000485182

Beck, A. K., Kelly, P. J., Deane, F. P., Baker, A. L., Hides, L., Manning, V., Shakeshaft, A., Neale, J., Kelly, J. F., Gray, R. M., Argent, A., McGlaughlin, R., Chao, R., & Martini, M. (2021). Developing a mHealth routine outcome monitoring and feedback app ("SMART Track") to support self-management of addictive behaviours. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 677637. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.677637

Bockmann, V., Lay, B., Seifritz, E., Kawohl, W., Roser, P., & Habermeyer, B. (2019). Patient-level predictors of psychiatric readmission in substance use disorders. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 828. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00828

Brownell, M. D., & Jutte, D. P. (2013). Administrative data linkage as a tool for child maltreatment research. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37(2-3), 120–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.09.013

Carlier, I. V. E., & Van Eeden, W. A. (2017). Routine outcome monitoring in mental health care and particularly in addiction treatment: Evidence-based clinical and research recommendations. Journal of Addiction Research & Therapy, 8(4), 1000332. https://doi.org/10.4172/2155-6105.1000332

Coker, A. O., Coker, O. O., & Sanni, D. (2018). Psychometric properties of the 21-item Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21). African Research Review, 12(2), 135–142.

Cutcliffe, J. R., Travale, R., Richmond, M. M., & Green, T. (2016). Considering the contemporary issues and unresolved challenges facing therapeutic communities for clients with alcohol and substance abuse. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 37(9), 642–650. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2016.1169465

Davies, S., Schultz, E., Raven, M., Wang, N. E., Stocks, C. L., Delgado, M. K., & McDonald, K. M. (2017). Development and validation of the agency for healthcare research and quality measures of potentially preventable emergency department (ED) Visits: The ED prevention quality indicators for general health conditions. Health Services Research, 52(5), 1667–1684.

de Andrade, D., Elphinston, R. A., Quinn, C., Allan, J., & Hides, L. (2019). The effectiveness of residential treatment services for individuals with substance use disorders: A systematic review. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 201, 227–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.03.031

Decker, K. P., Peglow, S. L., Samples, C. R., & Cunningham, T. D. (2017). Long-term outcomes after residential substance use treatment: relapse, morbidity, and mortality. Military Medicine, 182(1-2), e1589–e1595. https://doi.org/10.7205/MILMED-D-15-00560

Drake, S., Campbell, G., & Popple, G. (2012). Retention, early dropout and treatment completion among therapeutic community admissions. Drug and Alcohol Review, 31(1), 64–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-3362.2011.00298.x

Duncan, Z., Kippen, R., Sutton, K., Ward, B., Quinn, B., & Dietze, P. (2022). Health service use for mental health reasons in a cohort of people who use methamphetamine experiencing moderate to severe anxiety or depression. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-022-00889-9

Ferris, J., McElwee, P., Matthews, S., Smith, K., & Lloyd, B. (2016). Data linkage of healthcare services: Alcohol and drug ambulance attendances, emergency department presentations and hospital admissions (2004–09). Australasian Epidemiologist, 23(1), 37–45.

Goethals, I., Soyez, V., Melnick, G., De Leon, G., & Broekaert, E. (2011). Essential elements of treatment: A comparative study between European and American therapeutic communities for addiction. Substance Use & Misuse, 46(8), 1023–1031. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2010.544358

Gomez-Sanchez-Lafuente, C., Guzman-Parra, J., Suarez-Perez, J., Bordallo-Aragon, A., Rodriguez-de-Fonseca, F., & Mayoral-Cleries, F. (2022). Trends in psychiatric hospitalizations of patients with dual diagnosis in spain. Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 18(2), 92–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/15504263.2022.2053770

Gray, C., & Argaez, C. (2019). In residential treatment for substance use disorder: A review of clinical effectiveness. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31107598

Hjemsaeter, A. J., Bramness, J. G., Drake, R., Skeie, I., Monsbakken, B., Benth, J. S., & Landheim, A. S. (2019). Mortality, cause of death and risk factors in patients with alcohol use disorder alone or poly-substance use disorders: A 19-year prospective cohort study. BMC Psychiatry, 19(1), 1–9.

Ilgen, M., McKellar, J., & Tiet, Q. (2005). Abstinence self-efficacy and abstinence 1 year after substance use disorder treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(6), 1175–1180. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.73.6.1175

Iranpour, A., & Nakhaee, N. (2019). A review of alcohol-related harms: A recent update. Addict. Health, 11(2), 129–137. https://doi.org/10.22122/ahj.v11i2.225

Jakobsen, J. C., Gluud, C., Wetterslev, J., & Winkel, P. (2017). When and how should multiple imputation be used for handling missing data in randomised clinical trials—A practical guide with flowcharts. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 17, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-017-0442-1

Katz, I. R., Peltzman, T., Jedele, J. M., & McCarthy, J. F. (2019). Critical periods for increased mortality after discharge from inpatient mental health units: Opportunities for prevention. Psychiatric Services, 70(6), 450–456. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201800352

Kavanagh, A. (2020). Disability and public health research in Australia. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 44(4), 262–264. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.13003

Kavanagh, A. M., Krnjacki, L., Aitken, Z., LaMontagne, A. D., Beer, A., Baker, E., & Bentley, R. (2015). Intersections between disability, type of impairment, gender and socio-economic disadvantage in a nationally representative sample of 33,101 working-aged Australians. Disability and Health Journal, 8(2), 191–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2014.08.008

Kavanagh, A. M., Krnjacki, L., Beer, A., Lamontagne, A. D., & Bentley, R. (2013). Time trends in socio-economic inequalities for women and men with disabilities in Australia: Evidence of persisting inequalities. International Journal for Equity in Health, 12(1), 73. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-12-73

Keen, C., Young, J. T., Borschmann, R., & Kinner, S. A. (2020). Non-fatal drug overdose after release from prison: A prospective data linkage study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 206, 107707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107707

Kingston, R. E. F., Marel, C., & Mills, K. L. (2017). A systematic review of the prevalence of comorbid mental health disorders in people presenting for substance use treatment in Australia. Drug and Alcohol Review, 36(4), 527–539. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.12448

Krawczyk, N., Eisenberg, M., Schneider, K. E., Richards, T. M., Lyons, B. C., Jackson, K., Ferris, L., Weiner, J. P., & Saloner, B. (2020). Predictors of overdose death among high-risk emergency department patients with substance-related encounters: A data linkage cohort study. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 75(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2019.07.014

Krnjacki, L., Priest, N., Aitken, Z., Emerson, E., Llewellyn, G., King, T., & Kavanagh, A. (2018). Disability-based discrimination and health: Findings from an Australian-based population study. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 42(2), 172–174. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.12735

Lambert, M. J., Whipple, J. L., & Kleinstäuber, M. (2018). Collecting and delivering progress feedback: A meta-analysis of routine outcome monitoring. Psychotherapy (Chicago, Ill.), 55(4), 520–537. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000167

Leung, J., Chiu, V., Man, N., Yuen, W. S., Dobbins, T., Dunlop, A., Gisev, N., Hall, W., Larney, S., Pearson, S. A. D. L., & Peacock, A. (2023). All-cause and cause-specific mortality in individuals with an alcohol-related emergency or hospital inpatient presentation: A retrospective data linkage cohort study. Addiction. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.16218

Lewer, D., Freer, J., King, E., Larney, S., Degenhardt, L., Tweed, E. J., Hope, V. D., Harris, M., Millar, T., Hayward, A., Ciccarone, D., & Morley, K. I. (2020). Frequency of health-care utilization by adults who use illicit drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction, 115(6), 1011–1023. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14892

Lloyd, B., Zahnow, R., Barratt, M. J., Best, D., Lubman, D. I., & Ferris, J. (2017). Exploring mortality among drug treatment clients: The relationship between treatment type and mortality. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 82, 22–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2017.09.001

Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343.

Lubman, D. I., Matthews, S. H., Heilbronn, C., Killian, J. J., Ogeil, R. P., Lloyd, B., Witt, K., Crossin, R., Smith, K., Bosley, E., Carney, R., Wilson, A., Eastham, M., Kenne, T., & Shipp, C. D. S. (2020). The national ambulance surveillance system: A novel method for monitoring acute alcohol, illicit and pharmaceutical drug related-harms using coded Australian ambulance clinical records. PLoS One, 15(1), e0228316.

Mark, T. L., Tomic, K. S., Kowlessar, N., Chu, B. C., Vandivort-Warren, R., & Smith, S. (2013). Hospital readmission among medicaid patients with an index hospitalization for mental and/or substance use disorder. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 40(2), 207–221. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-013-9323-5

Maughan, B. C., & Becker, E. A. (2019). Drug-related mortality after discharge from treatment: A record-linkage study of substance abuse clients in Texas, 2006-2012. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 204, 107473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.05.011

McGovern, M. P., Lambert-Harris, C., Gotham, H. J., Claus, R. E., & Xie, H. Y. (2014). Dual diagnosis capability in mental health and addiction treatment services: An assessment of programs across multiple state systems. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 41(2), 205–214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-012-0449-1

McKetin, R., Degenhardt, L., Shanahan, M., Baker, A. L., Lee, N. K., & Lubman, D. I. (2018). Health service utilisation attributable to methamphetamine use in Australia: Patterns, predictors and national impact. Drug and Alcohol Review, 37(2), 196–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.12518

Milner, A., Kavanagh, A., McAllister, A., & Aitken, Z. (2020). The impact of the disability support pension on mental health: Evidence from 14 years of an Australian cohort. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 44(4), 307–312. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.13011

Mohamed, R., Wen, S. J., & Bhandari, R. (2022). Self-Help Group attendance-associated treatment outcomes among individuals with substance use disorder in short-term residential facilities. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 83(3), 383–391 <Go to ISI>://WOS:000812928500011.

Muller, A., Znoj, H., & Moggi, F. (2019). How are self-efficacy and motivation related to drinking five years after residential treatment? A longitudinal multicenter study. European Addiction Research, 25(5), 213–223. https://doi.org/10.1159/000500520

Nathan, S., Maru, K., Williams, M., Palmer, K., & Rawstorne, P. (2020). Koori voices: self-harm, suicide attempts, arrests and substance use among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adolescents following residential treatment. Health & Justice, 8(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40352-020-0105-x

Neale, J., Vitoratou, S., Finch, E., Lennon, P., Mitcheson, L., Panebianco, D., Rose, D., Strang, J., Wykes, T., & Marsden, J. (2016). Development and validation of 'SURE': A patient reported outcome measure (PROM) for recovery from drug and alcohol dependence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 165, 159–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.06.006

Nordeck, C. D., Welsh, C., Schwartz, R. P., Mitchell, S. G., Cohen, A., O'Grady, K. E., & Gryczynski, J. (2018). Rehospitalization and substance use disorder (SUD) treatment entry among patients seen by a hospital SUD consultation-liaison service. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 186, 23–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.12.043

Pasareanu, A. R., Vederhus, J. K., Opsal, A., Kristensen, O., & Clausen, T. (2016). Improved drug-use patterns at 6 months post-discharge from inpatient substance use disorder treatment: results from compulsorily and voluntarily admitted patients. BMC Health Services Research, 16, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1548-6

Queensland Health Information Knowledgebase (QHIK). (2023). https://qhdd.health.qld.gov.au/apex/f?p=103:MS_DETAIL:::::P4_MD_ID,P4_SEQ_ID:2,25464&cs=19F726A06F96971236AE076D72670028C

Queensland Hospital Admitted Patient Data Collection (QHAPDC) Manual 2022-2023. (2022).

Reif, S., Braude, L., Lyman, D. R., Dougherty, R. H., Daniels, A. S., Ghose, S. S., Salim, O., & Delphin-Rittmon, M. E. (2014). Peer recovery support for individuals with substance use disorders: assessing the evidence. Psychiatric Services, 65(7), 853–861. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201400047

Rockett, I. R. H., Putnam, S. L., Jia, H. M., Chang, C. F., & Smith, G. S. (2005). Unmet substance abuse treatment need, health services utilization, and cost: A population-based emergency department study. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 45(2), 118–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.08.003

Sklar, S. M., & Turner, N. E. (1999). A brief measure for the assessment of coping self-efficacy among alcohol and other drug users. Addiction, 94(5), 723–729. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.94572310.x

Smith, W. T. (2020). Women with a substance use disorder: Treatment completion, pregnancy, and compulsory treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 116, 108045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108045

Sofer, M. M., Kaptsan, A., & Anson, J. (2018). Factors associated with unplanned early discharges from a dual diagnosis inpatient detoxification unit in Israel. Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 14(3), 137–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/15504263.2018.1461965

Sofin, Y., Danker-Hopfe, H., Gooren, T., & Neu, P. (2017). Predicting inpatient detoxification outcome of alcohol and drug dependent patients: The influence of sociodemographic environment, motivation, impulsivity, and medical comorbidities. Journal of Addiction, 2017, 6415831. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/6415831

Tisdale, C., De Andrade, D., Leung, J., Chiu, V., & Hides, L. (2021). Utilising data linkage to describe and explore mortality among a retrospective cohort of individuals admitted to residential substance use treatment. Drug and Alcohol Review, 40(7), 1202–1206. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.13279

United States. Department of Health and Human Services. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs and health. Department of Health & Human Services.

van Walraven, C., Bennett, C., Jennings, A., Austin, P. C., & Forster, A. J. (2011). Proportion of hospital readmissions deemed avoidable: a systematic review. CMAJ, 183(7), E391–E402. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.101860

van Walraven, C., Jennings, A., & Forster, A. J. (2012). A meta-analysis of hospital 30-day avoidable readmission rates. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 18(6), 1211–1218. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.2011.01773.x

Vanderplasschen, W., Colpaert, K., Autrique, M., Rapp, R. C., Pearce, S., Broekaert, E., & Vandevelde, S. (2013). Therapeutic communities for addictions: A review of their effectiveness from a recovery-oriented perspective. The Scientific World Journal. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/427817

Vasconcelos, S. C., Sougey, E. B., Frazao, I., Turner, N. E., Ramos, P. H., & de Costa Lima, M. D. (2016). Cross-cultural adaptation of the drug-taking confidence questionnaire drug version for use in Brazil. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 16(1), 55. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-016-0153-z

Vu, F., Daeppen, J. B., Hugli, O., Iglesias, K., Stucki, S., Paroz, S., Canepa Allen, M., & Bodenmann, P. (2015). Screening of mental health and substance users in frequent users of a general Swiss emergency department. BMC Emergency Medicine, 15, 27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12873-015-0053-2

Walley, A. Y., Paasche-Orlow, M., Lee, E. C., Forsythe, S., Chetty, V. K., Mitchell, S., & Jack, B. W. (2012). Acute care hospital utilization among medical inpatients discharged with a substance use disorder diagnosis. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 6(1), 50–56. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0b013e318231de51

Wang, P. S., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso, J., Angermeyer, M. C., Borges, G., Bromet, E. J., Bruffaerts, R., de Girolamo, G., de Graaf, R., Gureje, O., Haro, J. M., Karam, E. G., Kessler, R. C., Kovess, V., Lane, M. C., Lee, S., Levinson, D., Ono, Y., Petukhova, M., et al. (2007). Use of mental health services for anxiety, mood, and substance disorders in 17 countries in the WHO world mental health surveys. Lancet, 370(9590), 841–850. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61414-7

Wang, L., Homayra, F., Pearce, L. A., Panagiotoglou, D., McKendry, R., Barrios, R., Mitton, C., & Nosyk, B. (2019). Identifying mental health and substance use disorders using emergency department and hospital records: A population-based retrospective cohort study of diagnostic concordance and disease attribution. BMJ Open, 9(7), e030530. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030530

Weintraub, E., Dixon, L., Delahanty, J., Schwartz, R., Johnson, J., Cohen, A., & Klecz, M. (2001). Reason for medical hospitalization among adult alcohol and drug abusers. American Journal on Addictions, 10(2), 167–177 <Go to ISI>://WOS:000169367400006.

Willey, H., Eastwood, B., Gee, I. L., & Marsden, J. (2016). Is treatment for alcohol use disorder associated with reductions in criminal offending? A national data linkage cohort study in England. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 161, 67–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.01.020

Wynne-Jones, M., Hillin, A., Byers, D., Stanley, D., Edwige, V., & Brideson, T. (2016). Aboriginal grief and loss: a review of the literature. Australian Indigenous Health Bulletin, 16(3), 1–9.

Yedlapati, S. H., & Stewart, S. H. (2018). Predictors of Alcohol Withdrawal Readmissions. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 53(4), 448–452. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agy024

Zarkin, G. A., Bray, J. W., Babor, T. F., & Higgins-Biddle, J. C. (2004). Alcohol drinking patterns and health care utilization in a managed care organization. Health Services Research, 39(3), 553–569. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00244.x

Acknowledgements

The service provider provided funding and in-kind support for this project. The National Centre for Youth Substance Use Research at The University of Queensland are supported by Commonwealth funding from the Australian Government provided under the Drug and Alcohol Program. The authors acknowledge the Statistical Analysis and Linkage Unit of the Statistical Services Branch (SSB), Queensland Health for linking data sets used in this project.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to conceptualisation and made significant intellectual contributions to the study. Analysis and the first draft of the manuscript was written by Calvert Tisdale. All authors critically reviewed and contributed to all manuscript drafts. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

De-identified data was received and approved by The University of Queensland Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number: 2018001063).

Conflict of Interest

CT is completing a funded PhD scholarship from the service provider in the current study. JL, DD, and LH have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Appendix 3

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tisdale, C., Leung, J., de Andrade, D. et al. Investigating the Critical Period for Alcohol or Other Drug-Related Presentations Following Access to Residential Substance Use Treatment: a Data Linkage Study. Int J Ment Health Addiction (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-024-01248-6

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-024-01248-6