Abstract

Research on Student Evaluation of Teaching (SET) has indicated that course design is at least as important as teachers’ performance for student-rated perceived quality and student engagement. Our data analysis of more than 6000 SETs confirms this. Two hierarchical multiple regression models revealed that course design significantly predicts perceived quality more strongly than teachers, and that course design significantly predicts student engagement independent of teachers. While the variable teachers is a significant predictor of perceived quality, it is not a significant predictor of student engagement. In line with previous research, the results suggest it is important to highlight the vital impact of course design. The results are discussed particularly in relation to improved teaching practice and student learning, but also in terms of how student evaluations of teaching can be used in meaningful ways.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In a recent research synopsis published in Higher Education, Ellis (2022, p. 1268) states that “it [innovation in teaching and learning in postsecondary education] is increasingly important and difficult to analyse and understand as the complexity and interdependence of variables involved in learning and teaching grows.” This study is a contribution to understanding one aspect of that complexity, namely the relevance of Student Evaluation of Teaching (abbreviated to the standard term SET in this paper).

Research on SET indicates that course design is at least as important as teachers’ performance for students’ evaluation of study quality and student engagement (Biggs et al., 2022; Edström, 2008; Upsher et al., 2023). This study explores how well teachers and course design predict perceived quality as well as student engagement in a sample of Swedish psychology students including more than 6000 evaluations.

In accordance with the Swedish Higher Education Ordinance (1993, p. 100), students have the right to anonymously give feedback on each course, and since universities and colleges are obliged to carry out course evaluations, there is a large amount of data to analyze. To our knowledge, no one has previously used this study data for quantitative research-based analysis.

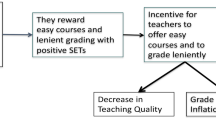

Course evaluations are intended to provide the experience of students as one input for teacher/s when evaluating a course and its results. Critics of SET point to a number of biases and methodological constraints, for instance that lecturer characteristics such as gender, attractiveness, and ethnicity affect students’ ratings (Carpenter et al., 2020; Nasser-Abu Alhija, 2017; Roxå et al., 2022; Binderkrantz and Bisgaard, 2023; Uttl et al., 2016). However, universities use course evaluations frequently, especially full course evaluations at the end of the semester (Eunkyoung & Dooris, 2020). This procedure seems to be an accepted method and is conducted worldwide (Nasser-Abu Alhija, 2017; Zabaleta, 2007). Many teachers de facto find this student feedback useful, particularly when it is focused on the course, and the students’ learning, rather than on the individual teacher (Edström, 2008). With a focus on course design rather than on the teacher, institutions could also prevent the risk of anonymous, abusive comments in the SETs, negatively affecting academics’ well-being, mental health, and career progression—particularly female academics and those from marginalized groups (Heffernan, 2023).

Faculty surveys, field experiments, and longitudinal studies have produced evidence that course evaluations are mostly valid, and provide important information for improved teaching, for instance in terms of clarity of explanation and encouragement of student participation (Murray, 1997; Nasser-Abu Alhija, 2017; Wright & Jenkins-Guarnieri, 2012). There is evidence that students’ ratings of their instruction are valid as measures for improving student achievement, and that students’ global ratings of courses, for instance in terms of perceived quality, predict student learning achievement (Cohen, 1981; Frick et al., 2009). Recent research also highlights the importance of curriculum design, and its influence both on students’ learning and their well-being (Upsher et al., 2023).

The use of student evaluation of teaching

SET can be used in various ways and with different aims and intentions, which are not always clear (Denson et al., 2010; Nasser-Abu Alhija, 2017; Zabaleta, 2007). Evaluations can be teacher-focused, in the sense that they are used for the teacher’s own development as well as for career opportunities, to inform the director of studies, or other relevant professionals at the department or the faculty of what is going on in the courses, or to signal when problems arise, as a kind of “alarm function.” SET can also be used as a basis for educational development work to improve teaching.

Previous research has shown that it is uncommon for evaluation forms to ask students to assess their own learning, even if this could be an important factor for educational development (Denson et al., 2010; Edström, 2008). It is more common for the primary focus to be rating the teacher’s performance in the classroom (Denson et al., 2010; Edström, 2008; Ginns et al., 2007; Marsh, 1984). However, it has not been confirmed that students learn more from highly rated teachers (Carpenter et al., 2020; Clayson, 2022; Uttl et al., 2016). In academia, we often tend to focus on what the teacher does, while we should instead take the heat off the teacher and focus on what the student does (Biggs et al., 2022). According to Kember, evaluation forms “will need to go beyond the almost ubiquitous teacher assessment instruments to examine curriculum variables” (Kember, 2004, p. 182). He further claims that course design and the development of the student’s motivation, which can inspire students to spend more time on their studies in order to achieve high-quality work, are factors that are at least equally important.

How, then, could SET obtained regarding courses, semester after semester, be used in a meaningful way for those responsible for teaching and curriculum design? An important and useful way to think about SET is to see it as a tool for course development and to improve student learning (Denson et al., 2010; Edström, 2008; Roxå et al., 2022). One approach to SET is to see it as an integral part of the scholarship of teaching (see Biggs et al., 2022; Edström, 2008) with a focus on what the students are doing and learning. SET can then be used as a component of the whole context of student-centered learning and constructive alignment (Edström, 2008). From a student learning perspective, integrating the syllabus and its learning outcomes, teaching, assessment, and evaluation, captures the whole teaching context (Biggs et al., 2022). Thus, it is important not only to assess teachers’ performance in the classroom but also to assess course design, perceived quality, and student engagement. The Department of Psychology at Lund University has collected SETs for a number of years, and they cover learning outcomes, teaching, assessment, course design, engagement, and quality, i.e., a very broad aspect of the teaching context.

Perceived quality

Previous research has indicated significant positive correlations between students’ global ratings of courses (e.g., indicating how much one agrees with the statement “Overall this was an outstanding course”) and student learning achievement, measured through objective tests (Frick et al., 2009). In the same study by Frick and colleagues, it was found that students who see themselves as masters of the course objectives (rather than partial masters or non-masters) rate the course as “great” to a larger extent. It was also found that expected or received course grades are very weakly associated with the perceived overall quality. One study found that statements such as “the course was challenging and interesting” and “the assessment methods and tasks in this course were appropriate given the course aims” were significant predictors of course quality among students (Denson et al., 2010, p. 348).

Student engagement

Student engagement is a complex concept that contains cognitive, emotional, and behavioral dimensions and components, and comprises both the individual and the context (Alvarez-Huerta et al., 2021; Appleton et al., 2008; Finn & Zimmer, 2012; Fjelkner, 2020). Importantly, student engagement involves both time and effort (Kahu, 2013), and the workload can be measured both in terms of actual hours and the perception of workload (Kember, 2004). One important conclusion from Kember’s study is that the non-subjective measure of workload and one’s perception of it do not always match. Thus, one can have a high workload without perceiving it as such, and vice versa.

Previous research has found positive associations between student engagement and, among other things, self-efficacy, motivation, time management, student performance, self-regulation toward goals, and learning outcomes (Alvarez-Huerta et al., 2021; Finn & Zimmer, 2012; Fjelkner, 2020; Kahu, 2013). Student engagement is an important variable to consider in order to improve the effectiveness of instruction, for instance, with regard to learning outcomes, and there is a growing number of instruments with adequate psychometric properties that measure student engagement, making it a “useful variable for data-driven decision-making efforts in schools” (Christenson et al., 2012, vi/7).

Student evaluation of teaching in this study

The standardized evaluation form that is used at the Department of Psychology at Lund University, and from which the study data derive, was developed based on identified needs and pedagogical considerations among teachers, on dialogues between study directors and the committees at the department, and in accordance with the guidelines at Lund University. The previous evaluation forms were considered too general and abstract. Consequently, there was a need to establish a more unified form for all the programs and courses in the organization. The new evaluation form features more detailed questions and places a greater emphasis on student-centered learning. An advantage of the standardized evaluation form is that most items are student-focused rather than teacher-focused. For instance, the students are asked to rate their own goal achievement for each learning outcome in the syllabus, as well as their own level of engagement in the course. Furthermore, the evaluation form comprises a wide range of items that capture metacognitive processes and learning activities, such as independent and critical thinking, and the incorporation of knowledge into a broader perspective. Although not scientifically validated, these items have evolved through rigorous discussions to improve teaching and study quality at the department.

The evaluation form has been used over many years on most courses and programs in the department and has thus generated a large amount of data. We therefore saw an excellent opportunity to systematize and analyze all these student ratings in order to gain insights into students’ perceptions of quality and what affects their own engagement. This can, in our view, also be relevant in other contexts where the relationship between SETs and course design is being considered.

Aims and research questions

The primary aim of this study is to understand the variables that predict perceived quality as well as engagement from a student perspective. What determines quality is an important topic, and there is still a need for empirical evidence. The study is based on a sample size of more than 6000 evaluations capturing many important aspects of the teaching context. The findings of the study therefore have the potential to make a solid contribution to the field and could thus be useful to professionals in the context of higher education.

We think a deeper understanding of these two variables can form an important element in educational development work and for improved teaching practice. The study could also serve to improve student-centered perspectives on learning and student engagement. In our study, we were particularly interested in investigating how the variables course design and teachers are related to student engagement and perceived quality. However, we were also interested in investigating how these two variables relate to other variables in the evaluation form, including course climate, assessment demand, seminars, and lectures. Thus, our aim is to answer the following three questions:

-

1.

How do student engagement and perceived quality relate to other student evaluation variables? We expect both teachers and course design to have at least a small positive correlation to course design and quality.

-

2.

Which of teachers and course design most strongly predicts student engagement?

Based on the previous literature indicating the importance of course design for student engagement, we hypothesize that course design predicts student engagement more accurately than teachers does (H1).

-

3.

Which of teachers and course design most strongly predicts perceived quality by students?

Based on the previous literature indicating the importance of course design for perceived quality, we hypothesize that course design predicts perceived quality more accurately than teachers does (H2).

Method

Participants

We analyzed 6342 course evaluations from the Department of Psychology. The data was gathered from the freestanding courses in psychology (N = 4933), the Master of Science program in psychology (N = 806), and the Bachelor of Science program in behavioral science (N = 604). The course evaluations might not all be independent, as the same student may have completed several evaluations. The evaluations are dated from 2016 to 2021 and involved course evaluations from 427 courses. On average, approximately 40% of the students per course completed the course evaluation.Footnote 1 There were 841 missing values and 1195 data points with the answer “don’t know,” indicating that the student missed or did not participate in the object of inquiry. These data points were removed. Out of the 6342 respondents, 569 completed evaluations in which they answered a question about gender; 153 (27%) were male, and 416 (73%) were female. A total number of 1011 answered a question about their previous amount of university credits. Of these, 110 (11%) had never studied before, 378 (37%) had studied 1–60 credits, 176 (17%) had studied 61–150 credits, and 347 (34%) had studied more than 150 credits. In Sweden, 30 credits equal one semester of university studies, and there are two semesters a year.

Instruments

Student engagement

Student engagement is composed of students’ self-reported level of engagement, activity, and number of study hours a week. The first two items were answered on Likert scales ranging from 1 to 5 (Don’t agree to agree). The number of hours a week was answered on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 6 in 10-h intervals (0–10 h a week in 10-h steps to > 50 h). We used the average of the questions. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.73, and McDonald’s omega was 0.74.

Course design

The course design scale was composed of the sum of students’ responses to whether they found the course to (a) have a well-defined structure, (b) have explicit and well-defined aims, (c) have encouraged their own critical thinking, (d) have encouraged further studies, (e) have enhanced their ability to incorporate knowledge in a broader theoretical perspective, and (f) have given them new knowledge and new insights. The scale also included two items regarding the appropriateness and relevance of the assessment in relation to the learning outcomes. All these questions were answered on Likert scales ranging from 1 to 5 (Don’t agree to agree). We used the average of the questions. Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was 0.86 and McDonald’s omega 0.90.

Teachers

Students’ evaluation of their teachers comprises three items asking students to rate the teachers’ ability to (a) be structured when lecturing, (b) create enthusiasm/involvement, and (c) clarify. All questions were answered on Likert scales ranging from 1 to 5 (Don’t agree to agree). We used the average of the questions. Both Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega were 0.84. There were no ratings for the Master of Science program in psychology on teachers in general but only for (a limited amount of) supervision, which we did not include.

Single-item variables

The instruments included five single-item variables answered on 5-point Likert scales with various description ends. A global item, perceived quality, was measured by the question “What did you think of the course as a whole?” with a scale from Very bad to Very good. Assessment demand was measured by asking students to evaluate the difficulty of the examinations in the course on a scale running from Low to High. Course climate was measured by the question, “How do you experience that the course group climate has been in your group during the course?” with a scale from Very bad to Very good. Lectures and seminars respectively were measured by having the students respond to “Assess [Lecture/Seminar] for the impact on your academic development” on a scale running from Low to High.

Procedure

The evaluations are created by an administrator in the Sunet Survey tool (https://www.sunet.se/services/samarbete/enkatverktyg) based on a standard form created by several department heads. Some minor tweaks are usually made to the standard form to account for different course literature in different courses.

An online link for the evaluation is then provided to the lecturer. The lecturer chooses to either provide the link to the students in the classroom so the students can use their mobile phones to fill out the evaluation directly or put the link out on the students’ online course platform for them to fill it out in their own time. The latter option often involves the lecturer also sending out reminders to the students to complete the evaluation. The evaluations are anonymous. As the data is filled in, it is gathered online in Sunet Survey, where the administrator summarizes it in comprehensible tables and descriptives for the lecturer. A second option exists to pull the data with the raw numbers from the Sunet Survey, which was used to gather all the data in this study. The raw data from all the modules and all the course evaluations were pulled separately and then compiled together to create the dataset in this study.

Ethical statement

The Department of Psychology values the important input from students and encourages the students to fill out the evaluation forms. The lecturer often sends out reminders to fill out the evaluation. While no informed consent was formally obtained, the students were informed that the evaluations were completely voluntary and anonymous. They were also informed that there were no “penalties” for not filling out the evaluation, nor any benefits for filling out the evaluation. In summary, participation was voluntary, anonymity was guaranteed, and the students were informed about this. We assessed that the benefits outweighed the risk of potential harm, which we consider to be very low as the nature of the questions does not imply any impact.

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The study has been performed in full accordance with the Swedish Ethical Review Act, and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the ethics committee at the Department of Psychology, Lund University.

Data analysis

To understand how student engagement and perceived quality relate to other student evaluation variables, we conducted Pearson correlations between all the study variables. Single-item variables can be statistically problematic due to their ordinal nature (i.e., they include few possible steps; Wu & Leung, 2017) and in the case of this study, they also showed relatively high skewness and kurtosis (Table 1). To deal with this, we also performed Spearman’s rank correlations (see Supplementary Material Table S1), which did not deviate substantially from the Pearson correlations.

We used similar analytic approaches to evaluate which of teacher and course design best predicted student engagement (H1) and student perceived quality (H2). This included hierarchical multiple regression where course design was entered in the first step (i.e., student engagement/perceived quality ~ course design) and compared against a null model. We compared these models against models that added teachers (i.e., student engagement/perceived quality ~ course design + teachers). We ran ANOVA to test whether the latter models including teachers as a predictor explained significantly more variance in student engagement/quality than the models that only included course design.

The models predicting student engagement reported in the main manuscript had two outliers excluded and the models predicting quality broke assumptions of linearity, homoscedasticity, and normality. We tested several ways of dealing with these issues before arriving at these decisions, including adding a quadratic term of course design when predicting student engagement, and conducting logistic ordinal regression when predicting quality, which also was a way of dealing with the ordinal nature of the single-item quality variable (see Supplementary Material pp. 2–5). Importantly, the results of all these different analyses converged, and we chose to report those that were easiest to interpret for the reader.

Further, we performed three hierarchical multilevel models with quality and engagement as the outcome that included random effects of classes, courses, and classes nested in courses. These revealed that a substantial proportion of the variance in both student engagement and quality was explained by the class and the course. Classes and courses explained 3–6% of the variance in quality on top of course design and teachers (conditional R2 = 0.55–0.58; marginal R2 = 0.50–0.55) and 2–3% of the variance in student motivation on top of course design and teachers (conditional R2 = 0.09–0.10; marginal R2 = 0.07). However, the fixed effects of the study variables in focus, course design and teachers, aligned with the results of the hierarchical multiple regressions in the paper. We also had to remove classes and courses with fewer than ten students, so reducing the sample size in the model. Due to this, and the increased complexity that adding hierarchical multilevel models would have caused for the audience for this paper, we chose to report these in the Supplementary Material (Tables S4–9).

Alpha, effect size interpretation, and R packages

A detailed description of the statistical analysis, including assumption descriptions of the regression models, can be found in the Supplementary Material. Alpha was set to 0.05. Based on empirical effect sizes from research on individual differences (Gignac & Szodorai, 2016), we interpreted significant correlations at 0.10, 0.20, and 0.30 as the lower border for small, moderate, and strong correlations, respectively. All analyses were conducted in R (R Core Team, 2019) using RStudio (RStudio Team, 2020). The following R packages were used for data cleaning and analysis: Tidyverse (Wickham et al., 2019), Psych (Revelle, 2021), Hmisc (Harrell, 2019), apaTables (Stanley, 2021), rio (Chan et al., 2018), lmBeta (Behrendt, 2014), magrittr (Bache et al., 2020), Stargazer (Hlavac, 2018), tibble (Müller et al., 2021), car (Fox & Weisberg, 2019), Foreign (R Core Team et al., 2022), MASS (Ripley et al., 2022), and reshape2 (Wickham, 2020).

Results

All numerical scales averaged above 3.5 on the 5-point scale. Course climate (M = 4.29) scored the highest, and assessment demand (M = 3.66) was the lowest among the variables (Table 1). The generally high scores are in tandem with the notably high skewness and kurtosis for some of the scales (perceived quality, course design, and lectures). These are above 1 but not over the commonly accepted limit of 2 (George & Mallery, 2018). All variables contained more than 1000 observations, with assessment demand having the highest number (N = 5162).

Correlations between student evaluation variables

The criterion variables of the study, student engagement and perceived quality, had a small significant correlation to each other (r = 0.16, p < 0.001; Table 2). Student engagement correlated moderately to the first main predictor, course design (r = 0.26, p < 0.001) but non-significantly to the second main predictor, teachers (p > 0.05). Perceived quality correlated more strongly to course design than to teachers (r = 0.72 and 0.58, respectively, p < 0.001 for both). The only predictor variable that correlated more strongly to student engagement than to perceived quality was assessment demand (r = 0.25, p < 0.001 and r = 0.03, p = 0.032, respectively). Generally, student engagement and perceived quality are dissociated; and all predictor variables, except for assessment demand, have a strong relationship to perceived quality that is stronger than to student engagement.

Course design predicts student engagement independent of teachers

Course design, not teachers, predicts student engagement (Table 3). To examine the influence of course design and teachers on student engagement, we ran a hierarchical multiple regression with course design in step 1, adding teachers in step 2. Course design was significantly better than the null model (F (1, 211) = 21.06, p < 0.001), explaining 8.6% of the variance in student engagement. Teachers did not significantly add any explained variance in step 2 (p > 0.05). The standardized beta coefficient of course design increased when accounting for teachers. The step 2 model explained 9.3% of the variance in student engagement. Thus, H1, stating that course design predicts student engagement more accurately than teachers, was confirmed.

Course design predicts perceived quality more strongly than teachers

We ran a similar hierarchical multiple regression with course design and teachers as predictors but with perceived quality as the criterion variable (Table 4). The step 2 model explained 58% of the variance, and teachers significantly added 6.9% explained variance in step 2 (R2 change = 0.069, p < 0.01) compared to step 1. Thus, teachers explains perceived quality independently of course design. On the other hand, course design was a stronger predictor than teachers in step 2 (ß = 0.598 and 0.317, respectively). Thus, both course design and teachers explain unique variance in perceived quality, but course design is the stronger predictor. Considering the ordinal nature of the perceived quality scale, we also computed ordinal logistic regression. These results did not deviate from the models reported here (see Supplementary Material). In sum, H2, stating that course design predicts perceived quality more accurately than teachers, was confirmed.

Discussion

This study is a contribution to the call by Ellis (2022, p. 1277) to “identify which aspects of the learning experience should be attenuated if improvements to outcomes are sought.”

In line with our two formulated hypotheses, our results confirm that course design is a stronger predictor than teachers of both perceived quality and student engagement. We base our findings on a large dataset spanning several years and thus believe that these results, to some extent, can be generalized in at least a Swedish social science context.

Our findings confirm previous claims concerning SET, namely, to not solely focus on teachers’ performance in the classroom (Biggs et al., 2022; Denson et al., 2010; Edström, 2008; Ginns et al., 2007; Marsh, 1984) but also focus on the impact of the course design. We validate this through our regression models, showing that the course design is a stronger predictor of perceived quality and student engagement compared to teachers’ performance. Although teacher performance is a significant predictor of perceived quality, the results suggest that teachers have the most influence on perceived quality and student engagement when designing the course. For instance, a well-defined structure, well-defined explicit aims to incorporate knowledge in a broader theoretical perspective, and the encouragement of critical thinking are crucial factors for both perceived quality and student engagement. Our correlational results align with the regression models, and the larger sample sizes for these correlations increase the strength and generalizability of these findings (Table 2). For example, the correlation between teachers and perceived quality includes 2098 responses. A potential threat to the findings above is the problem of strictly separating the rating of the teacher’s ability to be structured in the classroom and the rating of the course design itself, for instance, because of perceiving the teacher as responsible for the course design. This might explain why ratings of teachers and course design overlap.

A further contextual factor that decreases the generalizability and which possibly could explain the greater role of course design compared to the teacher is that the sample consists of psychology students at a social science faculty. In contrast to some other educational settings, such as medical programs and engineering programs, in general, the respondents in the present study have fewer teacher-led hours per week. In Sweden, the average for humanities, social sciences, law, and theology is 8 h of teacher-led instruction per week, while students in natural sciences, technology, and pharmacology can count on an average of 15 h of teacher-led contact time per week (Berlin Kolm et al., 2018). The course design may therefore fulfill a more important function for the students than the teacher. It might be the case that a lot of contact time and more frequent interaction with the teacher means less time for reflection, and the course design may thus become less important. Thus, future research should compare the importance of teachers in different disciplines and programs with different prerequisites for teacher-led hours per week.

As can be noted, assessment demand correlates with student engagement but only weakly with perceived quality. One explanation could be that students are very active and spend many hours to pass the course when the demands are perceived as being high. However, high demands do not imply that the course is perceived as being of high quality. When students rate assessment demand highly, they do not rate quality, lectures, seminars, course climate, or teachers particularly highly (Table 2). This raises the question of whether one should lower the demands to increase perceived quality or focus less on student-rated quality. This to some extent also contradicts the findings of Upsher et al. (2023) who found that when considering appropriate assessment methods followed by effective feedback, students saw the benefits of being academically challenged provided this is scaffolded appropriately.

Finally, concerning social contextual factors, our results indicate that the variable course climate is not related to student engagement. This may be another area for future research, as Upsher et al. (2023) demonstrated that curriculum designs signified by strong peer connection, teacher-student interaction, and communication were crucial to students’ learning and well-being—aspects that also relate to student engagement (Fjelkner, 2020).

Limitations and strengths

The data yields some limitations. First, the questions have been replaced at times, and thus, the sample size for various questions differs. Second, the range of 1 to 5 in the study scales quality, lectures, seminars, course climate, and assessment demand is not wide enough to be optimal as one-item continuous scales. The results are provided with corresponding ordinal analyses in the Supplementary Material with minimal differences. However, the third issue, the ceiling effect of almost all scales, indicates that most students gave very high ratings (mean values over 4 on a 5-point scale) on these small-range scales, which can imply several conclusions. It could mean that students, in general, are very content. It could also indicate selection bias, such that only content students partake in course evaluations. For instance, previous research has indicated that students who attribute more value to SET also provide higher rating scores (Carpenter et al., 2020; Nasser-Abu Alhija, 2017). Future research will have to provide answers to these questions.

We recommend that course evaluations in the future should extend the number of questions asked for each construct (e.g., three 1–5 Likert questions to examine perceived quality). If constructs are measured with single-item scales, the Likert scale range should be an 11-point range, as is suggested to be the minimum range for appropriate one-item continuous scales (Wu & Leung, 2017). Generally, future course evaluations would benefit from more planning on how the data will be analyzed in the future, as well as making explicit the intentional purposes of student evaluations, what to ask for, and how they can be used systematically. Finally, the large number of variables, including many missing values, makes complex models more difficult since data points for every variable are necessary for such models.

The variables investigated in the study also imply conceptual limitations. For instance, quality contains many dimensions and can be measured in different ways. In our study, we were interested in the students’ overall experience of the course, and this was measured with a single global item. On the other hand, single global items are common in evaluation forms (Denson et al., 2010), as are subjective ratings of feelings, which have been shown to be more accurate in predicting life outcomes/behaviors, such as partner separation and job change, compared to a set of 17 demographic variables including, e.g., socioeconomic status (Kaiser & Oswald, 2022). The variable student engagement can be difficult to distinguish from student motivation, and the relationship between these two concepts can be debated (Appleton et al., 2008; Finn & Zimmer, 2012). As we see it, engagement and motivation are two distinct concepts. For example, a student can score high on intrinsic and extrinsic motivation without actually being engaged in their studies. A strength of the variable student engagement, as it is measured in the present study, is that it captures both the estimated measure in terms of hours spent on studies, but also the perceived level of engagement and activity. We think these three components capture the phenomenon as a whole.

This study is a cross-sectional survey and thus demonstrates a relationship that exists at a specific time, at a certain department, at a certain university, and in Sweden. Hence, we do not comment on causal relationships, which is not the purpose of this study either, and the results should be interpreted with caution. On the other hand, a strength of our study is that data collection has been carried out in the same way and in the same circumstances over time.

Implications and future research

We believe that improved teaching practice comprises teachers’ skills as well as student feedback. As we see it, the course evaluation form used in this study contains a plethora of student-focused items and exemplifies how course evaluations can be used in a meaningful way. The use of student-centered course evaluation is in line with previous research on integrating course evaluations as part of the scholarship of teaching and as a tool for course development (Biggs et al., 2022; Edström, 2008; Roxå et al., 2022).

The study could inspire researchers regarding how to process and interpret data from course evaluations and, in the long run, how the results can be implemented. For example, the findings in the present study can be indicative and supportive in developing courses in order to improve teaching practice, taking into account the impact of course design on both student engagement and perceived quality. For example, well-thought-out course design can contribute to a higher degree of engagement, which in turn increases student success and potentially also course throughput. It could also contribute to preventing students from dropping out and increase the probability of retaining students, a common challenge in academia. Course design, in terms of clear course policies, procedures, and guidelines, as well as student motivation and satisfaction, among other variables, is associated with student retention (see, for instance, Eather et al., 2022) as well as student well-being (Upsher et al., 2023).

Had it been possible, we would have compared the above results to ones with grades. The data is anonymous, and our results say nothing about the students’ teacher-graded performance or how sustainable their knowledge is. In future studies, we would want to integrate students’ real grades, course throughput, and other objective measures.

One could also investigate the current variables with respect to the amount of teacher-led hours, which may vary between courses and programs. Furthermore, one could also investigate the goals and aims of the various education courses and programs with regard to the course evaluation variables. The sample includes only psychology students but comprises different courses and programs, which may differ in terms of their goals and aims. We believe that this could have an impact on student engagement. Finally, we would suggest investigating how the students’ own estimates of the learning outcomes relate to variables such as engagement, level of difficulty, assessment, and quality.

In this study, we sought to highlight the systematic use of student-centered course evaluations in combination with an explicit intention about their purpose, which we believe could function as one important constituent, among others, for improved teaching practice. This study contributes to discussions on perceived quality and student engagement within higher education at a collegial level, both in management groups and in teaching teams, with a focus on student learning.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Notes

We did not have access to the number of registered students at the courses. However, our data showed that, on average, 15 students (SD = 10) completed the course evaluation per course, and a standard course at the department had 40 students.

References

Alvarez-Huerta, P., Muela, A., & Larrea, I. (2021). Student engagement and creative confidence beliefs in higher education. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 40, 100821. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2021.100821

Appleton, J., Christenson, S., & Furlong, M. (2008). Student engagement with school: Critical conceptual and methodological issues of the construct. Psychology in the Schools, 45(5), 369–386. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20303

Bache, M. B., Wickham, H., Henry, L., & RStudio. (2020). magrittr: A forward-pipe operator for R. V. 2.0.1. (Computer software). https://cran.rproject.org/web/packages/magrittr/index.html. Accessed 19 Feb 2024.

Behrendt, S. (2014). lm.beta: Add standardized regression coefficients to lm-objects. V. 1.5–1. (Computer software). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=lm.beta. Accessed 19 Feb 2024.

Berlin Kolm, S., Svensson, F., Bjernestedt, A., & Lundh, A. (2018). Lärarledd tid i den svenska högskolan. En studie av scheman. (Teacher-led time in Swedish higher education. A study of schedules). Report 2018:15, Swedish Higher Education Authority. Lärarledd tid i den svenska högskolan (larandeochledarskap.se)

Biggs, J., Tang, C., & Kennedy, G. (2022). Teaching for quality learning at university (5th ed.). Open University Press.

Binderkrantz, A. S., & Bisgaard, M. (2023). A gender affinity effect: The role of gender in teaching evaluations at a Danish university. Higher Education, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-023-01025-9

Carpenter, S. K., Witherby, A. E., & Tauber, S. K. (2020). On students’ (mis)judgments of learning and teaching effectiveness. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 9(2), 137–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2019.12.009

Chan, C., Chan, G. C., Leeper, T. J., & Becker, J (2018). rio: A Swiss-army knife for data file I/O. (Computer software). https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/rio/index.html. Accessed 19 Feb 2024.

Chen, H., Cohen, P., & Chen, S. (2010). How big is a big odds ratio? Interpreting the magnitudes of odds ratios in epidemiological studies. Communications in Statistics: Simulation and Computation, 39(4), 860–864. https://doi.org/10.1080/03610911003650383

Christenson, S. L., Reschly, A. L., & Wylie, C. (Eds.). (2012). Handbook of research on student engagement. New York: Springer Science + Business Media. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-2018-7

Clayson, D. (2022). The Student Evaluation of Teaching and likability: What the evaluations actually measure. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 47(2), 313–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2021.1909702

Cohen, P. (1981). Student ratings of instruction and student achievement. A meta-analysis of multisection validity studies. Review of Educational Research, 51(3), 281–309.

Denson, N., Loveday, T., & Dalton, H. (2010). Student evaluation of courses: What predicts satisfaction? Higher Education Research & Development, 29(4), 339–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360903394466

Eather, N., Mavilidi, M. F., Sharp, H., & Parkes, R. (2022). Programmes targeting student retention/success and satisfaction/experience in higher education: A systematic review. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 44(3), 223–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2021.2021600

Edström, K. (2008). Doing course evaluation as if learning matters most. Higher Education Research & Development, 27, 95–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360701805234

Ellis, R. A. (2022). Strategic directions in the what and how of learning and teaching innovation—A fifty-year synopsis. Higher Education, 84(6), 1267–1281. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00945-2

Eunkyoung, P., & Dooris, J. (2020). Predicting student evaluations of teaching using decision tree analysis. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45(5), 776–793. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2019.1697798

Finn, J. D., & Zimmer, K. S. (2012). Student engagement: What is it? In S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Why does it matter? In Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 97–131). Springer.

Fjelkner, A. (2020). Business students’ perceptions of their readiness for higher education studies and its correlation to academic outcome. Journal for Advancing Business Education, 2(1), 74–92.

Fox, J., & Weisberg, S. (2019) car: An {R} C´companion to applied regression, third edition. (Computer software). Thousand Oaks CA: Sage. URL: https://socialsciences.mcmaster.ca/jfox/Books/Companion/. Accessed 19 Feb 2024.

Frick, T., Chadha, R., Watson, C., Wang, Y., & Green, P. (2009). College student perceptions of teaching and learning quality. Educational Technology Research and Development, 57, 705–720. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-007-9079-9

George, D., & Mallery, P. (2018). Reliability analysis. Chap. 7. In IBM SPSS Statistics 25 Step by Step (15th ed.). Routledge.

Gignac, G. E., & Szodorai, E. T. (2016). Effect size guidelines for individual differences researchers. Personality and Individual Differences, 102, 74–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.06.069

Ginns, P., Prosser, M., & Barrie, S. (2007). Students’ perceptions of teaching quality in higher education: The perspective of currently enrolled students. Studies in Higher Education, 32(5), 603–615. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070701573773

Harrell, F. E. Jr., with contributions from Charles Dupont and many others. (2019). Hmisc: Harrell Miscellaneous. R package V. 4.3–0. (Computer software). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=Hmisc. Accessed 19 Feb 2024.

Heffernan, T. (2023). Abusive comments in student evaluations of courses and teaching: The attacks women and marginalised academics endure. Higher Education, 85(1), 225–239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00831-x

Hlavac, M. (2018). stargazer: Well-formatted regression and summary statistics tables. R package. V. 5.2.2. (Computer software). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=stargazer. Accessed 19 Feb 2024.

Kahu, E. R. (2013). Framing student engagement in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 38(5), 758–773. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2011.598505

Kaiser, C., & Oswald, A. J. (2022). The scientific value of numerical measures of human feelings. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 119(42). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2210412119

Kember, D. (2004). Interpreting student workload and the factors which shape students’ perceptions of their workload. Studies in Higher Education, 29(2), 165–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/0307507042000190778

Marsh, H. (1984). Students’ evaluations of university teaching: Dimensionality, reliability, validity, potential biases, and utility. Journal of Educational Psychology, 76(5), 707–754. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.76.5.707

Müller, K., Wickham, H., Francois, R., & Bryan, J. (2021). tibble: Simple data frames. (Computer software). 2021. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/tibble/index.html. Accessed 19 Feb 2024.

Murray, H. (1997). Does evaluation of teaching lead to improvement of teaching? International Journal for Academic Development, 2(1), 8–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144970020102

Nasser-Abu Alhija, F. (2017). Guest editor introduction to the special issue “Contemporary evaluation of teaching: Challenges and promises.” Studies in Educational Evaluation, 54, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2017.02.002

R Core Team, Bivand, R., Carey, V. J., DebRoy, S., Eglen, S., Guha, R., Herbrandt, S., et al. (2022). foreign: Read Data Stored by “Minitab”, “S”, “SAS”, “SPSS”, “Stata”, “Systat”, “Weka”, “dBase”, ...V. 0.8–82. (Computer software). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=foreign. Accessed 19 Feb 2024.

R Core Team. (2019). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria. URL: https://www.R-project.org/. Accessed 19 Feb 2024.

Revelle, W. psych: Procedures for personality and psychological research. (2021). V. 2.1.9. (Computer software). Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois, USA. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=psych. Accessed 19 Feb 2024.

Ripley, B., Venables, B., Bates, D. M., Hornik, K., Gebhardt, A., & Firth, D. (2022). MASS: Support functions and datasets for Venables and Ripley’s MASS. V. 7.3–56). (Computer software). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=MASS. 19 Feb 2024.

Roxå, T., Ahmad, A., Barrington, J., Maaren, J., & Cassidy, R. (2022). Reconceptualizing student ratings of teaching to support quality discourse on student learning: A systems perspective. Higher Education, 83(1), 35–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00615-1

RStudio Team. (2020) RStudio: Integrated development for R. RStudio, PBC. (Computer program). Boston, MA URL. http://www.rstudio.com/. Accessed 19 Feb 24.

Stanley, D. (2021). apaTables: Create American Psychological Association (APA) Style Tables. V 2.0.8. (Computer software). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=apaTables. Accessed 19 Feb 2024.

Swedish Higher Education Ordinance. (1993). Ministry of Education and Research, 1993, 100.

Upsher, R., Percy, Z., Cappiello, L., Byrom, N., Hughes, G., Oates, J., Nobili, A., Rakow, K., Anaukwu, C., & Foster, J. (2023). Understanding how the university curriculum impacts student wellbeing: A qualitative study. Higher Education, 86(5), 1213–1232. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00969-8

Uttl, B., White, C., & Gonzalez, D. (2016). Meta-analysis of faculty’s teaching effectiveness: Student Evaluation of Teaching ratings and student learning are not related. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 54, 22–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2016.08.007

Wickham, H., Averick, M., Bryan, J., Chang, W., D’Agostino McGowan, L., François, R., Grolemund, G., et al. (2019). Welcome to the Tidyverse. Journal of Open Source Software, 4(43), 1686. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.01686

Wickham, H. (2020). reshape2: Flexibly reshape data: A reboot of the reshape. Package. V1.4.4. (Computer software]. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=reshape2. Accessed 19 Feb 2024.

Wright, S. L., & Jenkins-Guarnieri, M. A. (2012). Student evaluations of teaching: Combining the meta-analyses and demonstrating further evidence for effective use. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 37(6), 683–699. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2011.563279

Wu, H., & Leung, S. O. (2017). Can Likert scales be treated as interval scales? A simulation study. Journal of Social Service Research, 43(4), 527–532. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2017.1329775

Zabaleta, F. (2007). The use and misuse of student evaluations of teaching. Teaching in Higher Education, 12(1), 55–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510601102131

Funding

Open access funding provided by Lund University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Levinsson, H., Nilsson, A., Mårtensson, K. et al. Course design as a stronger predictor of student evaluation of quality and student engagement than teacher ratings. High Educ (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-024-01197-y

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-024-01197-y