Abstract

The digitalization of transaction processes through tools such as electronic invoicing (e-invoicing) aims to improve tax compliance and reduce administrative costs. Another important aspect of digitalization is its potential to reduce tax fraud. We exploit the comprehensive introduction of e-invoicing in Italy in 2019 and examine the effect of increased domestic tax enforcement capabilities on cross-border value-added tax (VAT) fraud. As a proxy for this fraud, we make use of the discrepancy in trade data that are double-reported in both the importing and exporting country (trade data gap, TDG). We calculate the TDG for imports to Italy from all other EU countries at the most detailed product level. Our results suggest a significant decline in cross-border fraud in response to the introduction of mandatory e-invoicing, providing an important rationale for the application of this measure by other countries. Furthermore, we estimate that e-invoicing decreased the Italian VAT loss in 2019 by about € 2.2 billion to € 2.6 billion compared to 2018. In this context, we underpin the suitability of the TDG as an approach for the study of anti-fraud measures.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Digitalization promises to improve tax enforcement due to the acceleration of data collection that enables tax administrations to monitor transactions in real time (Jacobs, 2017). As a result, digitizing tax collection is gaining noticeable popularity in tax policy debates and is attracting increasing interest among academics. In this study, we examine the effect of the transition from paper-based to electronic invoicing (e-invoicing) on cross-border value-added tax (VAT) fraud. For this purpose, we use the Italian e-invoicing system, which became mandatory for almost all transactions between resident entities as of January 1, 2019.

Many non-European countries, especially within Latin America and Asia, implemented digitized transaction processes, i.e. through mandatory business-to-business (B2B) e-invoicing to monitor economic processes. In the European Union (EU), Italy is the first country to have introduced such a system on a mandatory basis for B2B and B2C (business-to-customer) transactions.Footnote 1 Italy has undertaken the introduction of e-invoicing on its own, i.e. without specific coordination with other EU Member States. Hence, the scope is limited to the national level. Therefore, we ask the question whether enhanced domestic tax enforcement capabilities have a significant deterrent effect on cross-border VAT fraud that accounts for a bulk of overall VAT gapsFootnote 2 within the EU (European Commission, 2016; Frunza, 2016; Braml & Felbermayr, 2021).Footnote 3

VATFootnote 4 as the main form of consumption tax is implemented in about 170 countries. In the countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), it generates approximately one-third of all tax revenue (OECD, 2020). This type of consumption tax has the potential to create high revenue at relatively low administrative and economic costs.Footnote 5 However, it is also prone to fraud as firms themselves collect the tax on behalf of the state. The tax is payable by the acquirer to the supplier, while the latter is obliged to forward the received VAT to the tax authorities after deducting input tax paid on own purchases. The damage resulting from organized VAT fraud, under which the supplier does not remit the received tax from the acquirer, is partially reduced if the right to deduct the input VAT for the supplier is refused and is thus limited to the tax amount on his or her profit margin (“value added”). However, the fraudster's plunder and thus the VAT loss increase significantly if the fraudster is able to avoid paying the input VAT. Zero-rated cross-border transactions open up this possibility. The fraudster imports goods from another EU Member State without VAT, sells them with VAT on the domestic market and disappears with the gross amount received.Footnote 6 Due to the disappearance, the fraudster is called “missing trader” and the straightforward name of this scheme is ‘missing trader intra-Community’ (MTIC) fraud.Footnote 7 Based on the cross-border element, recent studies have shown that the product-specific gap between the export reported by the exporting country and the corresponding import reported by the importing country (trade data gap, TDG), serves as an indicator of cross-border VAT fraud (Braml & Felbermayr, 2021; Bussy, 2020; Stiller & Heinemann, 2019, 2023).Footnote 8

With e-invoicing, the risk of fraud detection increases since the invoice has to be sent electronically via a system of the tax administration that enables quicker cross-checks between VAT claimed and paid. The penalties imposed for not using the e-invoicing system, as well as the refusal to deduct VAT when the purchaser knew or ought to have been aware of the existence of VAT fraud, provide an incentive for honest businesses to avoid suspicious transactions. If e-invoicing prevents the fraudster’s domestic supplies, the fraudster imports less or no more. As a result, declared exports and undeclared imports decrease or honest importers replace the fraudster, increasing declared imports. In both cases, the TDG declines.

Therefore, we exploit a difference-in-differences model accounting for potential omitted variable bias including unit and time fixed effects. We obtain data on Italy's trade with the remaining EU countries for all products at the level of the 8-digit code of the Combined Nomenclature (CN), 12 months before and after the introduction of e-invoicing on January 1, 2019. As the control group, we use products that fall under the previously introduced reverse charge mechanism (RCM) and therefore should not be subject to VAT fraud. RCM applies to B2B transactions and is a VAT blocking mechanism under which the buyer is obliged to pay the VAT to the tax authorities instead of paying it to the supplier. Thus, the VAT does not come under control of the fraudster. Recent empirical studies confirm the fraud-reducing effect of the RCM (Buettner & Tassi, 2023; Bussy, 2020; Stiller & Heinemann, 2019, 2023). However, we provide additional empirical evidence for the effect of the RCM with regard to the Italian implementation.

We identify the difference in the TDG before and after the reform between products potentially not affected by e-invoicing (RCM products) as the control group and all remaining products (non-RCM products) as the treatment group.Footnote 9 We find that the introduction of e-invoicing is associated with a significant decrease in cross-border VAT fraud expressed by the TDG. The results hold when we replace the control group (RCM products in Italy) with non-RCM products in EU countries that did not adopt e-invoicing and had the highest VAT gaps in 2018 according to Poniatowski et al. (2020), i.e. Greece, Lithuania, Romania and Slovakia. Furthermore, we find a significant decrease in the TDG if we narrow down the treatment group to make treated products more similar to RCM products.

Using a simple back-of-the-envelope calculation, we estimate that e-invoicing tackled cross-border VAT fraud in a range from € 2.2 billion to € 2.6 billion from 2018 to 2019. Our results are close to the Italian estimates of an increase in VAT revenue in 2019 of about € 1.7 billion to € 2.1 billion euros (Italian Ministry of Economy & Finance, 2020). However, our model is able to isolate the effect of cross-border VAT fraud. Given that Italy detected around € 1 billion in cross-border fraud in 2019 and 2020 (European Commission, 2021a), e-invoicing has not completely extinguished fraud.

Our findings contribute to a better assessment of the impact of e-invoicing on cross-border VAT fraud, confirm the significant share of this fraud in total revenue losses and underpin the suitability of the TDG as an indicator for cross-border VAT fraud. Since administrative costs in relation to the system are low (running cost of up to € 20 million a year) a domestic e-invoicing system provides a promising way to tackle cross-border VAT fraud in other countries.

Tax research on digital tools, including e-invoicing systems, focuses on the potential to improve tax compliance and collection in developing countries (Alonso et al., 2021; Bellon et al., 2022; Bérgolo et al., 2018; Fan et al., 2020; Hernandez & Robalino, 2018; Lee, 2016; Mascagni et al., 2021; Ramirez et al., 2018; Templado & Artana, 2018) as well as cost implications for both tax administrations and firms (Giannotti et al., 2019). Although theoretical considerations on the use of digital tools against VAT fraud in Europe go back a long time (see e.g. Ainsworth, 2006), empirical studies on the tax fraud-reducing effect of digitalization are scarce. Most recently, Kitsios et al. (2022) conducted an empirical study that examines the impact of digitalization efforts on cross-border VAT fraud using aggregated trade data. They confirm that digitalization correlates with lower tax fraud. However, their analysis focus on the relationship between aggregated trade data within the EU and the Online Service Index conducted by the United Nations as proxy for digitalization efforts. Such a highly generalized index cannot disentangle single digital measures. Moreover, cross-border tax fraud is a product-specific phenomenon that can be studied only to a limited extent with aggregated data.

As part of the annual VAT gap study for all EU Member States, Poniatowski et al. (2022) find a statistically significant negative correlation between the VAT gap and (digital) reporting obligations, including VAT listing, Standard Audit File-Tax, real time and e-invoicing. However, this estimation aims to identify the overall impact of digital reporting obligations in the EU rather than single measures. Nevertheless, it shows the importance of improved tax reporting.

Against this background, the implication of certain digitalization measures with regard to cross-border tax fraud has been insufficiently examined. Such empirical evidence is essential to evaluate ongoing implementation efforts and to support tax policy in future debates as the digitalization of tax administrations become increasingly important. This demonstrates the example of the current debate on a harmonized e-invoicing system in Europe (European Commission, 2020). While especially in Latin America, e-invoicing is attested to have considerable anti-fraud potential (Barreix & Zambrano, 2018), the question remains how it affects the case of cross-border VAT fraud in Europe. We address this research gap by examining the introduction of e-invoicing in Italy in 2019 on B2B and B2C transactions using gaps in double-reported trade data between Italy and the remaining EU countries at the most detailed product code level of the CN.

With this paper, we contribute to the ongoing empirical research on the examination of measures against VAT fraud and its impact on tax revenues using trade data gaps as fraud proxy (Braml & Felbermayr, 2021; Bussy, 2020; Stiller & Heinemann, 2019, 2023). In this sense, we also contribute more broadly to the overall literature on the analysis of the TDG as a cross-border fraud indicator (Fisman & Wei, 2004; Javorcik & Narciso, 2008, 2017; Mishra et al., 2008; Stoyanov, 2012).

Additionally, our paper contributes to the emerging empirical research on the relationship between digitalization and tax fraud. Kitsios et al. (2022), Strango (2021) and Poniatowski et al. (2022) find that higher digitalization of tax reporting obligations is correlated with less (cross-border) tax fraud. All these papers, however, focus on aggregated country-level data and proxies for general digitalization efforts. We extend this literature stream i.e. by using disaggregated product-level data and a single reform, uncovering the impacts of digitalization on tax fraud on a more detailed level.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows. In Sect. 2, we provide the institutional background of the e-invoicing system in Italy and formulate our hypothesis in conjecture with the definition of our proxy for cross-border VAT fraud. In Sect. 3, we present the data and in Sect. 4 the identification strategy. Section 5 is devoted to the presentation and discussion of the main results. Section 6 addresses robustness checks and in Sect. 7, we describe and perform a quantification of the fraud. Section 8 concludes. We provide additional heterogeneity analyses in Section B in Appendix.

2 Hypothesis development

2.1 Reform background and theoretical considerations

In 2019, the obligation to send invoices electronically via the Italian exchange system (Sistema di Interscambio; SdI) came into force for the vast majority of Italian firms carrying out B2B and B2C transactions.Footnote 10 E-invoices fully replaced paper-based invoices for taxpayers with an annual turnover of more than € 65 thousand. According to the Italian Ministry of Economy and Finance (2018a), this threshold intends to cover 80% of all taxable persons in Italy. The initial start of the system dates back to June 2014, where e-invoicing became mandatory for transactions with ministries, tax agencies and national security agencies. From March 2015, all business-to-government (B2G) supplies were integrated into the system. This was followed by a voluntary adoption of e-invoicing for B2B in 2017. From July 2018, the use of the SdI was mandatory for the sale of fuels and became binding to all B2B and B2C transactions from January 1, 2019 (Italian Revenue Agency, 2021).

Italy enforces the system mainly by the imposition of different penalties when not using the SdI. These include the refusal of the input VAT deduction when no confirmed e-invoice is sent through the system and additional monetary fines.Footnote 11 The seller has to send the invoice file (Fattura PA) to the SdI, so that the tax authority acquires the information contained in the e-invoices in real time. However, in the first instance, the SdI only checks if the formal requirements are met. In a second step, the e-invoice data are transmitted to the tax authority that stores the e-invoices and uses automated and integrated processes to cross-check the consistency between the VAT declared and paid and also with other cross-border anti-fraud information sources (European Council, 2018; European Commission, 2021).Footnote 12 If the system accepts the formal validity, the seller obtains a receipt, while the buyer receives the invoice. Only through this procedure, the invoice is regarded as such for purposes of VAT and the acquirer can deduct the input VAT. Therefore, the taxable buyer should be sensitive to require an e-invoice before transferring the gross amount to the seller.Footnote 13

Moreover, fines are imposed when the SdI is not applied. The fines range between 90% and 180% of the VAT. As an exception, the regulations allowed taxpayers to avoid these fines if the e-invoice was uploaded to the SdI until the 15th of the following month during the first half of 2019.Footnote 14 Since then, an e-invoice has to be sent directly to the SdI to avoid the penalties.

In order to theoretically assess the compliance effects of e-invoicing, we distinguish between two broad types of non-compliance. On the one hand, non-compliant firms, in particular those under-reporting sales or over-reporting costs, and on the other hand the organized MTIC fraud. We focus on the latter, but presenting a short theoretical framework for both to justify how our model is able to isolate the effects on cross-border VAT fraud conceptually.

When an invoice has been sent through the SdI, the tax authority receives the transaction-based information shortly after and can perform cross-checks between taxpayers. This limits non-compliant firms to adjust their accounting records afterward. Therefore, keeping a certain level of tax evasion is thus very likely to be costlier after the reform, as these practices can potentially be exposed more quickly. In addition to increased costs of evasion, several benefits result from the system. Namely, the automation of invoice retention obligations, lower cost per invoice compared to paper invoices, streamlining of accounting processes and the availability of real-time accounting data (Italian Revenue Agency, 2021). Shedding light on the effect of switching from paper-based to electronic invoicing, Bellon et al. (2022) find for Peru that firms indeed increase reported sales, purchases and VAT liabilities on average. These results are stronger among small firms since they tend to be less compliant. For the introduction of e-reportingFootnote 15 of sales in Ethiopia, Mascagni et al. (2021) find that reported sales increase; however, firms also adjust reported cost upward. Therefore, curbing the positive tax collection effect by the reform, which nevertheless showed a net positive effect. Moreover, Fan et al. (2020) find a significant increase in VAT revenues after the introduction of digitally encrypted invoices in China.

In contrast to the non-compliance behaviour described above, organized cross-border fraud is likely to react differently to increasing digitalization. VAT fraudsters might hardly profit from any of the structural benefits resulting from the process digitalization. The reform confronts them with increased costs of fraud that can jeopardize their activities. Note that MTIC fraud differs from cases in which seller and buyer have an incentive to under- or over-report sales and costs, or even consensually carry out transactions without invoicing. Fraudsters make profits from the VAT collected that is not remitted to the tax authority. Regardless of whether the buyer is involved in the fraud, the invoice sent to the buyer determines the success. If the buyer is involved, the right to deduct the input VAT is essential to keep an overall profit from the scheme for the criminal organization.Footnote 16 In the event that the buyer is unaware, the fraudster has to pretend to be a compliant firm, as an invoice and inconspicuous transaction circumstances are central for the buyer to obtain an input tax deduction. The imposed penalties arising from not applying the electronic system should increase the incentive of taxpayers even further to take care not making business with fraudsters. Thus, the use of the SdI should increase the costs of fraudsters in each case (selling to involved or uninvolved firms) since the fraudster has to provide an unsuspicious e-invoice through the SdI for that a registration has to take place. Compared to paper invoices, electronic invoicing additionally poses a higher risk of detection for fraudsters, as the tax authority can cross-check the invoice data in real time.

2.2 E-invoicing and trade data gap

A growing literature that examines the effectiveness of measures against VAT fraud exploits discrepancies in double-reported trade data (Bussy, 2020; Kitsios et al., 2022; Stiller & Heinemann, 2019, 2023). Fisman and Wei (2004) first used these discrepancies to study tariff evasion on the product level between China and Hong Kong. This approach has found wide use in other studies related to tariff evasion (Javorcik & Narciso, 2008, 2017; Mishra et al., 2008; Stoyanov, 2012). In accordance to the vast literature, we define the ratio of exports to corresponding imports of product \(p\) at the 8-digit CN product level at time \(t\) from exporting country \(e\) to importing country \(i\) reported by country \(e\) and \(i\), respectively, as the trade data gap (TDG). Taking the natural logarithm on both sides leads to

Equation (1) implies positive ln TDG values for \(\frac{{{\text{Export}}}_{{\text{eipt}}}}{{{\text{Import}}}_{{\text{eipt}}}}>1\) (case with prevalent fraud) and negative values for \(\frac{{{\text{Export}}}_{{\text{eipt}}}}{{{\text{Import}}}_{{\text{eipt}}}}<1\), as well as the value zero for \(\frac{{{\text{Export}}}_{{\text{eipt}}}}{{{\text{Import}}}_{{\text{eipt}}}}=1\). Besides fraud, ln TDG can occur due to different valuations of exports and imports. Since exports are valued as free-on-board, while imports include also cost of insurance and freight, the latter should be slightly higher by default resulting in a slightly negative value (Eurostat, 2020).

European taxpayers operating across borders are generally obliged to report imports and exports not only in the domestic periodic VAT return but also in the Intrastat system. The application of the TDG as proxy for cross-border VAT fraud is based on the theoretical argument that the fraudster does not report imports in the Intrastat system, while the exporter does. Since the fraudsters import goods on a zero-VAT basis, i.e. without payable input VAT, there is no incentive to comply with the obligations to file tax returns and Intrastat declarations.Footnote 17 However, we only observe respective gaps if exporters report trade within the Intrastat systems, while fraudulent importers fail to do so. We rely on the assumption that exporters fulfill their reporting obligations. This assumption can be justified by the fact that the exporter does not have to be aware of the fraud. Even if involved, compliance with the declaration requirements could be used as an argument by the exporter to be unknowingly involved in the fraud in case of detection. Therefore, the exporter can claim the refund of the input tax. Such a line of reasoning does not help the fraudulent importer, as the tax due is not paid to the tax authority. The declaration of imports could possibly help the fraudster not to be detected immediately by the tax office. However, this strategy in the absence of tax payment can only work for a short time until the tax authority finds out that domestic VAT is not remitted.

Even though the implementation of Italy’s e-invoicing in 2019 targets domestic supplies and therefore has no direct impact on cross-border transactions. We expect a significant impact on TDG since e-invoicing increases the tax enforcement capabilities on domestic supplies and hence increases the costs for cross-border VAT fraud. As outlined above, the cross-border transaction is essential for the fraud scheme. If the fraudsters would acquire goods domestically, they would have to pay the input tax to the supplier and claim its refund from the tax authority. Importing the goods at zero rate from another EU Member State is less risky for the fraudsters. It has a liquidity advantage and allows them to charge a price lower than the net purchase price, as the fraudsters consider VAT as revenue, unlike the compliant taxpayers. Hence, they can undercut market prices for i.e. selling higher quantities (e.g. European Court of Auditors, 2019).

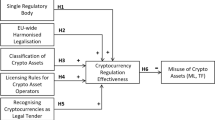

E-invoicing intends to increase compliance by non-compliant firms and to tackle cross-border fraud. We formulate the assumption that the TDG mainly reacts to the effect of e-invoicing on fraud instead of compliance changes by non-compliant firms. We argue that these firms are still incentivized to report an EU-import. Failure to declare the imports would preclude the deduction of the purchasing costs for income tax purposes. Against this background, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis

The introduction of mandatory e-invoicing in Italy significantly reduces the trade data gap and thus cross-border VAT fraud.

3 Data

We use Eurostat's freely accessible database,Footnote 18 which contains detailed information on exports and imports between EU Member States (intra-EU) for all goods distinguished by the 8-digit CN code, the most detailed level available. Data on intra-EU trade are based on Intrastat declarations by taxpayers exceeding the country-specific threshold (see Table 12 in Appendix) (Eurostat, 2020). To construct the TDG, we collect monthly data on traded products using the 8-digit CN code for intra-EU-imports to Italy from the 27 remaining EU countries reported by Italy and the corresponding intra-EU-exports reported by the remaining EU countries. For a robustness check, we extend this by analogous data for Greece, Lithuania, Romania and Slovakia as importing countries. The observation period ranges from January 2018 to December 2019, resulting in 12 months before and 12 months with mandatory e-invoicing in Italy (introduction of e-invoicing on January 1, 2019). Observations including the value of zero for exports and imports were omitted from the sample since our dependent variable requires nonzero values. We further exclude fuels from our baseline sample since these products were already subject to mandatory e-invoicing six months prior to the general introduction. Table 7 in Appendix presents the distribution of products across the product codes of our sample.

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics for \({\text{ln TDG}}\) by treatment and control group. We use products falling under the reverse charge mechanism (RCM) as control group. These products should be unaffected by the fraud-reducing effect of the reform. We discuss the selection of this control group when we present the identification strategy below. We expect the mean \({\text{ln TDG}}\) to be (if at all slightly below) zero in case without fraud. The mean \({\text{ln TDG}}\) of the control group consisting of RCM products (TREAT = 0) before and after e-invoicing at 0.0266 and − 0.0332, respectively, is relatively stable and close to zero. In contrast, treatment products (TREAT = 1) show about ten times higher mean \({\text{ln TDG}}\) before e-invoicing (0.2624), which indicates potential fraud within this group. The respective mean of 0.0683 for TREAT in the period with e-invoicing is significantly lower and close to zero; however, it is still higher than its counterpart for the control group, indicating that some fraud activity could be left over. Nonetheless, these descriptive results give suggestive evidence that the mandatory e-invoicing system in Italy significantly affected the treatment group.

4 Identification strategy

4.1 Empirical framework

According to our hypothesis, the application of the mandatory e-invoicing in Italy reduces cross-border VAT fraud. Thus, we estimate the following difference-in-differences model:

\({{\text{POST}}}_{t}\) is a dummy equal to one from January 2019 on and zero otherwise. \({{\text{TREAT}}}_{p}\) is a dummy equal to one if a product \(p\) belongs to the treatment group and zero if the product is protected by RCM.Footnote 19

All non-RCM and non-FUELS products form the treatment group. As the control group, we use products that were most likely not affected by fraud in the run-up to the mandatory e-invoicing. Findings by Buettner and Tassi (2023), Bussy (2020), and Stiller and Heinemann (2019, 2023) provide theoretical and empirical support that the introduction of the RCM substantially tackles cross-border VAT fraud in the importing country as it excludes the fraudster from receiving the output tax. This domestic reverse charge procedure, implemented on certain products and services, shifts the liability to pay the VAT from the supplier to the buyer in B2B transactions. Therefore, fraudsters cannot take control over the VAT anymore, eliminating the incentive to trade with these products for fraudulent purposes. To provide additional evidence, we estimate the effect of the Italian RCM following the approach of Stiller and Heinemann (2023). For brevity, we refer to the description of the exercise and the results in Table 8 in Appendix. RCM significantly reduced the \({\text{ln TDG}}\) in the two main implementation events around April 2011 and May 2016 (see Table 8, Panel C, Column 3, Appendix) indicating a substantial decrease in cross-border VAT fraud.

Due to the hypothesized fraud-reducing effect of e-invoicing in Italy, we predict a negative coefficient \(\delta\) in Eq. (2). Our panel data enables us to include unit and time fixed effects. \({\gamma }_{{\text{ep}}}\) reflects unit fixed effects as exporting-country-8-digit CN code combinations and \({\lambda }_{t}\) represents time fixed effects as continuous month-year combinations.

\(X_{{{\text{ept}}}}\) is a vector of control variables that contains the variables \({\mathrm{THRESHOLD\ GAP}}_{{\text{et}}}\), \({\mathrm{REDUCED\ A}}_{p}\), \({\mathrm{REDUCED\ B}}_{p}\), \({\mathrm{REDUCED\ C}}_{p}\) and \({{\text{EURO}}}_{{\text{e}}}\). \({\mathrm{THRESHOLD\ GAP}}_{{\text{et}}}\) captures differences in reported exports and imports due to different thresholds for reporting obligations for these trade flows that each country is required to set within the Intrastat system (see for thresholds Table 12, Appendix).Footnote 20 The variables \({\mathrm{REDUCED\ A}}_{p}\), \({\mathrm{REDUCED\ B}}_{p}\) and \({\mathrm{REDUCED\ C}}_{p}\) are dummies equal to one if the VAT rate in Italy on the specific product \(p\) is reduced to 10%, 5% or 4%, respectively, and zero otherwise. These dummies serve to capture VAT rate effects.Footnote 21 If fraudsters take the VAT rate into account, as higher rates should technically increase their profits, reduced rate products should be unattractive for them. We therefore expect a lower \({\text{ln TDG}}\) for these products. Further, we include \({{\text{EURO}}}_{e}\) that serves to absorb differences in trade data that could occur due to currency conversion (Loschky, 2006). The variable drops as soon as unit fixed effects are included. The error term is represented by \({\varepsilon }_{{\text{ept}}}\). All variables with explanations are displayed in Table 10 (Appendix). See also Table 11 (Appendix) for descriptive statistics on all control variables.

4.2 Event study and parallel trends

Given our difference-in-differences approach, treatment and control groups must share similar pre-trends. We provide graphical and statistical evidence to test this assumption. Graphic A of Fig. 1 displays the simple mean values of \({\text{ln TDG}}\) for treatment and control group by each period. Treatment products show a significantly higher mean \({\text{ln TDG}}\) before the reform compared to control products. It is noteworthy that the control group exhibits stronger fluctuations than the treatment group. However, before the reform, both groups exhibit similar directions in terms of increases and decreases of \({\text{ln TDG}}\). In period 0 (January 2019) and 1 (February 2019), the treatment group shows a decreasing trend of \({\text{ln TDG}}\) in both months, while the control group increases. Beyond that, the treatment group lingers at a significantly lower level as prior to the reform, close to the level of the control group. A sharp decline of \({\text{ln TDG}}\) can also be seen already in the two months before the event. However, this occurred equally for both groups, potentially caused by reporting issues.

Development of ln TDG. Notes Graphic A shows the mean value of \({\text{ln TDG}}\) as defined in Eq. (1) for treatment (red) and control (blue) by each month within the 24-month observation window. Graphic B shows the event-study coefficients from Eq. (3). Grey lines indicate the 90% confidence interval (Color figure online)

To test the parallel trends assumption more formally and to obtain dynamic effects, we estimate an event study specification of Eq. (2) that reads

in which \({D}^{k}_{t}=1[t=Period_0+k]\) and thus includes dummies turning one when the reform is \(k\) months from the start of the reform in period \(k=0\). The period immediately prior to introduction (\(k=-1\)) is not included in the equation and represents the base period, which is set to zero by convention. This dynamic specification includes periods before (pre-trends) and after (dynamic effects) the introduction of e-invoicing. We expect \({\delta }_{k}\) to be around zero for \(k<0\) and negative for \(k\ge 0\). Graphic B of Fig. 1 presents the estimated event study coefficients. The picture reveals that with the exception of the periods close to the ends of the observation window, the coefficients are close to zero directly prior to the reform. In the first period of the event, the coefficient drops visibly and stays negative for the majority of the postreform periods.

We keep the observation window short so that other policy changes aiming at increasing compliance interfere minimally with pre- and post periods. However, we want to discuss briefly the implementation of certain other measures during the sample period.Footnote 22,Footnote 23 Before the SdI was technically ready to process cross-border invoice data in 2022, Italy first demanded so-called Spesometro declarations. From 2011 to 2018, Italian taxpayers were obliged to report invoice data including import and export information in a quarterly or bi-annual report. In 2019, the Esterometro replaced the system by implementing a mandatory monthly filing of VAT sales and purchases made to or acquired from non-resident businesses since the SdI did not include cross-border invoice data. However, these reports did not release taxpayers from the obligation to file Intrastat declarations.Footnote 24 In general, it cannot be ruled out that a shortening of the reporting period has an impact on cross-border VAT fraud. However, the planned introduction of Esterometro has been postponed to April 30, 2019. Moreover, the Italian Ministry of Economy and Finance has also extended filing deadlines of the predecessor regulation (Spesometro) for 2018.Footnote 25

5 Results

Table 2 presents our baseline results for \({\text{ln TDG}}\) displaying all variables included in the model. The coefficient of POST is negative, but statistically significant only when including unit or alternative time fixed effects and suggests a general decreasing trend of \({\text{ln TDG}}\) in Italy. TREAT, on the other side, shows positive coefficients throughout the specifications indicating that the treatment group suffered from higher fraud prior to the reform compared to the control group. This result confirms our rationale for identifying RCM products as a control group.

The main variable of interest is the interaction of both variables. The corresponding coefficient is negative and statistically significant throughout the specifications (see Table 2, Columns 1 to 8). Noteworthy, fixed effects control for a large share of the variation as the adjusted R2 increases significantly after including unit fixed effects. Simultaneously, the coefficient of the interaction drops from − 0.136 in Column 3 to − 0.073 in Column 4 (see Table 2). The exclusion of the control variables does not change the results (see Table 2, Column 6).

For robustness, we modify unit and time fixed effects and include them on a higher hierarchy. We use exporter-4-digit HS codes instead of exporter-8-digit CN codes regarding unit fixed effects and quarter-years instead of month-years as time fixed effects. As expected, including the alternative set of fixed effects lowers the adjusted R2 since these fixed effects capture less variation. The interaction effect increases slightly in magnitude to − 0.103 (see Table 2, Columns 7 and 8). Nevertheless, we believe that the specification from Column 5 gives us the best estimate, adequately controlling for omitted variables and lets us observe the preferred within variation of exporter-8-digit CN codes combinations. Finding this robust negative effect throughout the specifications strongly supports our hypothesis that mandatory e-invoicing reduced cross-border VAT fraud in Italy. Regarding Column 5 (Table 2), the application of e-invoicing in Italy is associated with a reduction of the TDG by approximately 7%.

Our first control variable EURO is positively correlated with the dependent variable (see Table 2, Column 2; due to collinearity with unit fixed effects, the variable drops out from Column 3). This result could be explained by the fact that intra-Eurozone fraud avoids currency exchange risks and is therefore more lucrative. Concerning THRESHOLD GAP, the negative coefficient is plausible as the variable sets the reporting threshold for exports in relation to the reporting threshold for imports. An increase in this variable reflects a relative increase in non-reported exports to imports, which reduces \({\text{ln TDG}}\). Note that country-specific estimations for non-reportable trade below the thresholds are not included in the trade figures. REDUCED A and (in some cases) REDUCED C show a negative and statistically significant coefficient as well, indicating that reduced VAT rate products are less appealing to fraudsters. This result is reasonable since a lower tax rate reduces their profits. REDUCED B is omitted from all specification including fixed effects due to collinearity. We note that the control variables do not change the results in any way. However, we keep them throughout the regressions and robustness checks later on, as they might capture some specific fraud behavior that is not controlled for by fixed effects.

6 Robustness checks

6.1 Alternative control group

In our first robustness test, we want to address the concern that trade with RCM products could still contain fraud, since e.g. B2C transactions are not fully covered by this mechanism. We are convinced by the empirical evidence and our exercise from Table 8 (Appendix) that the RCM removes fraud to a significant extent. This can be underpinned by the nature of cross-border VAT fraud, which is based on high-value transactions taking place at the B2B rather than the B2C level. Nevertheless, we want to address this concern. Therefore, we additionally make use of an alternative control group to check the robustness of our initial results. We modify our empirical setting and replace the initial control group (RCM products in Italy) with non-RCM products in other importing countries that did not adopt e-invoicing. Considering the 2018 VAT gap study by Poniatowski et al. (2020), Greece, Lithuania, Romania and Slovakia show similar levels of VAT gaps for the year 2018 and are therefore used as an alternative control group.

According to the above-mentioned strategy, we modify Eq. (2) as follows. The dummy variable TREAT takes on the value of one if the importing country is Italy and zero if the importing country is Greece, Lithuania, Romania or Slovakia.Footnote 26 Note that the respective equation gets an additional subscript \(i\) since the variation now also stems from the fact that we observe different importing countries and country pairs. The correlation matrix (Table 13, Panel B) and the descriptive statistics (Table 14) regarding the alternative control group are displayed in Appendix.

Referring to the descriptive statistics, we can observe that the mean \({\text{ln TDG}}\) of the control countries is relatively low and increases slightly from 0.0167 to 0.0302 after the introduction of mandatory e-invoicing in Italy. Despite the high VAT gaps, the low TDG indicates less cross-border VAT fraud activity in these countries before the Italian reform. Figure 2, Graphic A displays the differences in the mean \({\text{ln TDG}}\) for treatment (Italy) and control countries (Greece, Lithuania, Romania and Slovakia) regarding non-RCM products. The level of the Italian \({\text{ln TDG}}\) is visibly higher pre-reform and significantly closer to the control units afterward. Graphic B of Fig. 2 presents the event-study coefficients that show a sharp decline from period 0, staying constantly on a negative level.

Development of ln TDG—alternative control group. Notes Graphic A shows the mean value of \({\text{ln TDG}}\) as defined in Eq. (1) for treatment (red) and alternative control (blue) group (non-RCM products in Greece, Lithuania, Romania and Slovakia) by each month of the 24 months observation window. Graphic B shows the event-study coefficients from Eq. (3) using the alternative control group. Grey lines indicate the 90% confidence interval (Color figure online)

Table 3 displays the regression table for our alternative control group specification. We can observe a negative and statistically significant interaction throughout the specifications. The coefficient of interest is − 0.201 (see Table 3, Column 4) in the main specification. Thus, non-RCM products in Italy show a considerably lower TDG after the introduction of e-invoicing compared to the control country units. Noteworthy, the magnitude is higher compared to the baseline results, reflecting a more severe decrease of the treatment group compared to the control group. This might be due to a spillover effect of the Italian reform on the control countries. In this regard, we observe a positive coefficient for the main effect POST when it is included. This indicates that within our alternative sample, and in the absence of the reform, the TDG would have developed slightly upward. This is contrary to our baseline results (we observed a downward trend in the absence of the reform) and may be indicative for the spillover hypothesis. Finally, the coefficient on TREAT is positive when included. This confirms that treatment products suffered higher fraud activities prior to the reform.

6.2 Alternative dependent variables

In this section, we check if our baseline results hold when we change the dependent variable. First, we use \({\text{ln TDG}}\) calculated analogous to Eq. (1) using quantities instead of values. Second and third, we winsorize and trim the value-based \({\text{ln TDG}}\) at the bottom and top 1% by each exporting country, respectively. Therefore, we try to control for outliers in the data. Fourth and fifth, we examine the effect on the natural logarithm of export and import, respectively. In this case, we include the opposite trade flow (ln Import or ln Export, respectively) into the model as control variables. Therefore, we test our estimation assumptions used in the following section, according to which we expect to observe falling exports and/or rising imports.

Table 4 presents the results for all described alternative dependent variables. The coefficient of − 0.063 for \({\text{ln TDG}}\) in quantities (see Table 4, Column 1) is statistically significant and comparable to our initial result (− 0.073 in Table 2, Column 5). This strongly confirms our baseline result and indicates that fraudsters underreport values and quantities, which strengthens the assumption that missing traders fail to report imports at all. Winsorizing and trimming \({\text{ln TDG}}\) and therefore excluding outliers hardly affect the quantity of the estimator (see coefficient in Table 4, Columns 2 and 3). That gives us additional confidence regarding our baseline model.

Interestingly, the coefficient on the interaction regarding ln Export is insignificant (see Table 4, Column 4), suggesting that export values did not change after e-invoicing. On the other side, we find a positive and statistically significant coefficient regarding ln Import (see Table 4, Column 5). This result could be indicative that honest traders took over trade from fraudsters that left the market after the reform. Unlike the fraudsters, we expect compliant traders to declare the imports due to business expense deduction, which results in a positive coefficient. To this extent, it seems reasonable that export reporting did not change. However, our model cannot pick up the reason why we observe or not observe certain reactions in specific export and import behavior. Using trade data gaps is more sophisticated in detecting changes in fraudulent trade. Therefore, we leave the interpretation to the reader and assume in the following section that changes in \({\text{ln TDG}}\) can occur due to both decreases in exports and increases in imports.Footnote 27

6.3 Restricted treatment group

In this section, we restrict the group of treated products to those that fall under the same 2-digit and 4-digit HS code as the RCM products, respectively.Footnote 28 This procedure modifies the treatment group with the aim to make it more comparable to the control group as the baseline treatment group covers many different products. Note that throughout RCM products form the control group and do not change compared to the baseline approach. Table 5 presents the results. The statistically significant coefficient of the interaction within the 2-digit HS code sample is very close to our main result (− 0.074 in Table 5, Column 1 vs. − 0.073 in Table 2, Column 5). The corresponding coefficient from the regression based on the 4-digit HS code is with − 0.215 almost three times larger (Table 5, Column 2). In this case, the sample size is significantly smaller due to the reduction of the treatment group.Footnote 29 However, we find significant effects also by decreasing the number of treatment products and making them theoretically more similar to the control products, which supports the suggestive evidence gained so far.

7 Quantification of fraud tackled by e-invoicing

The previous results provide suggestive evidence that e-invoicing tackled cross-border VAT fraud by decreasing the TDG. Throughout, the interaction coefficient \(\delta\) from Eq. (2) captures the decrease in the level of the TDG for treatment products due to e-invoicing. Therefore, exports (imports) of treatment products in 2018 were abnormally high (low) due to fraudulent activity. Mechanically, the TDG decreases when exports (imports) decrease (increase). Therefore, we use simple back-of-the-envelope calculations to estimate the amount of VAT revenue loss (\({\text{REVLOSS}}\)) in the year prior to the reform using the following formulas, separately based on exports and imports:

In simple terms, Eqs. (4) and (5) calculate the amount of export excess and import deficit resulting from abnormally high exports and abnormally low imports in 2018 backward from the TDG reduction observed with \(\delta\).Footnote 30 There are four different VAT rates (\({{\text{VAT}}}_{\tau }; \tau\)) for which we calculate \({\text{REVLOSS}}\) in Table 15 in Appendix. We use the sum of exports to Italy reported by the 27 exporting countries (EXPORT2018) and the sum of imports reported by Italy from the 27 exporting countries (IMPORT2018).

In general, the interaction coefficient \(\delta\) estimates the reduction of the TDG. Therefore, we recalculate the amount of exports or imports that have led to this increased TDG in 2018 compared to 2019. These exports and imports are the base of fraudulent trade assumed to be carried out domestically by fraudsters. Therefore, we multiply each export excess and import deficit with the respective VAT rate to obtain the amount evaded in the year prior to the reform. Table 15 (Appendix) outlines the detailed values used in the calculation steps. Note that in the case where Italy refused to refund input VAT to a taxable buyer, part of \({\text{REVLOSS}}\) was recovered. However, we could not find any statement of how much input VAT deduction was refused by Italy.

In the baseline regression, we estimate an unweighted average effect of the reform that could bias our estimation exercise if e.g. a product with significantly higher trade volume experiences a stronger or weaker decline after e-invoicing. To estimate \({\text{REVLOSS}}\), we re-run our baseline regression weighting each observation by export or import volume of a product relative to all other products prior to the reform, respectively. Combining this weighted approach with the estimation of export- or import-based values, gives us a range of four alternatives. If previously declared exports to the fraudsters are eliminated through e-invoicing, the TDG reduces (export-based estimation). The other possible outcome is that honest importers become more active after the fraudsters are pushed out of the respective market, which increases the declaration of imports, and therefore decreases the TDG (import-based estimation).

The results of the weighted regressions are displayed in Table 6. The coefficients of the interaction are statistically significant and reduced to − 0.056 using the export share as weight (Table 6, Column 3) and − 0.048 using the import share as weight (Table 6, Column 6) compared to the unweighted baseline result of − 0.073 (Table 2, Column 5). If we insert the two new coefficients into Eqs. (4) and (5), we obtain a range for \({\text{REVLOSS}}\) between € 2.2 billion and € 2.6 billion (see Table 15, Appendix, and in particular Columns 12 to 15).Footnote 31 Hence, e-invoicing tackled cross-border VAT fraud accounting for about 7% of overall uncollected VAT given the total VAT gap of Italy of € 32.415 billion in 2018.Footnote 32

The Italian Ministry of Economy and Finance (2020) estimates the effect of e-invoicing for 2019 using macro-level data and calculates an unexplained residual between actual VAT revenue and the VAT revenue theoretically paid based on the economic cycle of € 1.7 billion and € 2.1 billion. Note that this approach captures all compliance increases by e-invoicing regardless of the cross-border nature. Comparability to our estimate is limited since Italy estimates a figure for 2019, while we are estimating the amount of fraud that could have been carried out in 2018. However, Italy stated that they identified “companies involved in intra-Community fraud mechanisms carried out between the last months of 2019 and 2020, based on invoicing flows for non-existent transactions amounting to around EUR 1 billion” (European Commission, 2021). Together with our results, this indicates that e-invoicing initially reduced cross-border VAT fraud but did not eliminate the fraud activities entirely.

By nature, we lack of precise proxies with regard to tax fraud, but the estimation underpins the significant extent of cross-border VAT fraud and helps to assess the effects of the reform as precisely as possible. Considering the comparably low investment cost of about € 3.7 million and running cost of the mandatory e-invoicing system, amounting to € 10 to 20 million a year, our results provide a strong argument in favor of this tool for combating VAT fraud (Italian Revenue Agency, 2021; Italian Ministry of Economy and Finance, 2018a).Footnote 33

The estimation results are subject to some external constraints. Clearly, the observed VAT revenue and fraud-reducing effect is an Italian specific estimate. Since the level of pre-reform cross-border fraud is an important factor regarding the effectiveness of the mandatory e-invoicing, generalizations for other countries from the results need to be made with caution. As we discussed regarding the parallel trends assumption, we cannot rule out some anticipation of increased fraud in 2018.

8 Conclusion

The numerous measures taken against VAT fraud (such as RCM), as well as the ongoing significant revenue losses, make studies on the effectiveness of these countermeasures particularly important. In 2019, Italy introduced a mandatory e-invoicing system for B2B and B2C supplies, taking a pioneering role in the EU in the timely recording and control of transactions. This paper examines the effect of digitalization in form of e-invoicing in Italy on cross-border VAT fraud using discrepancies in double-reported trade data between Italy and the remaining EU Member States on product flows based on the 8-digit product code. As control group, we use products falling under RCM since recent empirical evidence suggests the fraud-eliminating effect of this measure. All other products serve as the treatment group.

We find a significant reduction of cross-border VAT fraud with the introduction of the mandatory e-invoicing system. This result holds for a number of robustness checks. Additionally, we quantify the reform in Italy using a back-of-the-envelope calculation and estimate that cross-border VAT fraud in 2018 led to VAT revenue losses between € 2.2 billion and € 2.6 billion tackled by the reform. Our findings indicate a desirable fraud-reducing effect of a mandatory e-invoicing system easily exceeding the set-up and running costs of such system. Even though the e-invoicing system covered only domestic transactions, it demonstrates a considerable deterrent effect on cross-border VAT fraud activities. The results provide key insights into the benefits of digitalization.

Notes

In many EU countries, e-invoicing is mandatory only for business-to-government (B2G) transactions (Giannotti et al., 2019). Other EU countries are planning to adopt or have already adopted e-invoicing on B2B and B2C supplies. An overview of the current legislative status can be found in country-specific factsheets provided by the European Commission: https://ec.europa.eu/digital-building-blocks/sites/display/DIGITAL/eInvoicing+Country+Factsheets+for+each+Member+State+and+other+countries. Accessed 19 January 2024.

VAT (compliance) gap is the difference between the VAT revenue that would be collected in the case of full compliance and the actual VAT revenue.

Some countries implemented a “Goods and Services Tax (GST),” for example, Australia, India or Canada. The GST is very similar to VAT because both tax the value added to the sale of products or services (OECD, 2020).

The design of the VAT makes it neutral with regard to business decisions. By principle, VAT does not affect the choice of the legal form, financing structure and investment projects. This applies not only to domestic activities but also to cross-border transactions. Taxation in the importing country (destination principle) links VAT to the place of consumption, making the location decision of companies irrelevant for this tax and considerably reducing the scope for tax planning (Cnossen, 1998; McLure, 1993).

The buyer must declare the import VAT (while the same amount can be deducted as input VAT). This reporting obligation is delayed because the import VAT is not collected at the border when the supply is made, but must be declared in the next regular VAT return. This creates a time lag during which fraudsters can intensively carry out EU imports and domestic supplies before the tax authority can detect the fraud (Sergiou, 2012).

MTIC fraud can be divided further into “acquisition fraud” and “carousel fraud.” The latter differs from the former in that the goods imported by the missing trader circulate, so that they are imported several times, allowing VAT to be evaded at each "turn" of the carousel.

Trade data gaps are extensively used in tariff evasion research; see e.g. Fisman and Wei (2004). However, there is inconsistency in terminology as some authors refer to the same measure as e.g. “Bilateral Discrepancy” (Braml and Felbermayr, 2021), “Trade Gap” (Javorcik and Narciso, 2008), “Evasion Gap” (Fisman and Wei, 2004) or “Reporting Gap” (Bussy, 2020) or other notations.

We exclude fuels from the sample since e-invoicing became mandatory during 2018 already. See Table 19 in Appendix for a detailed explanation of each product group.

According to the official EU website on the Italian e-invoicing system (https://ec.europa.eu/digital-building-blocks/wikis/display/DIGITAL/eInvoicing+in+Italy), the taxable person must be resident or have a permanent establishment in Italy.

Official FAQ of the Italian Revenue Agency. https://www.agenziaentrate.gov.it/portale/web/guest/schede/comunicazioni/fatture-e-corrispettivi/faq-fe/risposte-alle-domande-piu-frequenti-categoria/sanzioni. Accessed 27 July 2023.

As an exception, the Italian VAT law enables the buyer to send a self-e-invoice to the SdI to obtain the input VAT deduction in case the seller does not comply with the e-invoicing regulations. However, the tax authority can make the buyer liable of the VAT of the supplier and can pose a penalty up to a hundred percent of the tax, with a minimum of € 250.

See e.g. the explanations on the official website of the Italian Revenue Agency, https://www.agenziaentrate.gov.it/portale/web/guest/schede/comunicazioni/fatture-e-corrispettivi/faq-fe/risposte-alle-domande-piu-frequenti-categoria/sanzioni. Accessed 5 July 2023.

A reform that made the use of sales registration machines (SRMs) mandatory in a staggered roll-out. These SRMs communicate sales electronically to the tax authority.

If a missing trader A sells a good for 100 plus 20 VAT domestically to the involved firm B and B pays the gross amount of 120 to A, the scheme can only lead to a profit if A does not remit the 20 to the tax authority, while B gets a refund of 20.

The import is subject to an intra-Community acquisition in which the importer has to self-declare the import and the respective output VAT for the exporter in the other Member State. However, this VAT can be deducted immediately as input VAT and therefore has only importance for reporting. Thus, the VAT liability is transferred to the buyer regarding intra-Community transaction. Later, we will define the reverse charge mechanism (RCM) as the domestic transfer of tax payment liability from the supplier to the buyer. However, the mechanism behind intra-Community acquisitions is similar as the supplier does not charge VAT (it is zero-rated) and the buyer declares the VAT for the supplier and deducts this VAT as input tax in the same reporting period.

We use the dataset ‘EU trade since 1988 by HS2-4-6 and CN8’ with the code ‘DS-045409’ freely available at https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/main/data/database.

There is no change in product allocation between both groups within the observation period.

\(\mathrm{THRESHOLD GA}{{\text{P}}}_{{\text{et}}}={\text{ln}}\left(\frac{{{\text{THRESHOLD}}}_{{\text{et}}}}{{{\text{THRESHOLD}}}_{{\text{t}}}}\right)\). EU Member States are obliged to estimate missing trade due to thresholds, fraud and other reasons. However, since we obtain 8-digit CN codes from the bulk download option provided by Eurostat (see https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/bulkdownload), those estimations are excluded as they are indicated by alphanumeric product codes.

The reduced (10%, 5% and 4%) and standard (22%) VAT rates in Italy remain constant within the observation period. Including dummies that indicate reduced VAT rate leaves all other products to the baseline. This group consists of products falling under the standard VAT rate but also that are tax exempted. The list of tax exemptions can be found in Article 10 of the Presidential Decree No. 633/1972. Due to our observation window, we checked Article 10 effective from 3 Aug 2017 to 31 Dec 2019. However, there are no clearly distinguishable products since mostly services are covered or products that are only tax exempted under certain circumstances or with certain characteristics.

The official announcement of the adoption of e-invoicing can be traced back to the official Italian Budget Law for 2018 (Law no. 205/2017) made public December 27, 2017. Unfortunately, checking for anticipation is hampered by a significant change in the importing Intrastat threshold, which increased from € 200 thousand in 2017 to € 800 thousand in 2018 (Eurostat, 2017, 2021). This came along with the obligation to declare monthly Intrastat reports instead of quarterly if a taxpayer exceeded € 200 thousand in EU-imports in one of the quarters 2017 (Italian Revenue Agency, 2017). Note that there is no estimation for trade carried out below the threshold. Hence, for pure reporting reasons, a higher import threshold leads to less reported imports and a higher trade gap, holding the export threshold constant. Controlling for THRESHOLD GAP may not capture this difference when treatment and control group products are differently affected, which we can neither confirm nor reject. For the years from 2020 onward, limiting the period to December 2019 rules out confounding effects of additional measures such as the tax receipt lottery for B2C transactions and possible other fraud possibilities due to COVID-19.

Already mid-2017, Italy widened the scope of the split payment mechanism from transactions to the public administration in 2015 to all companies controlled by the public administration and to companies listed in the FTSE-MIB index of the Italian Stock Exchange (Italian Ministry of Economy and Finance, 2018b). Under this mechanism, the buyer pays the VAT to a blocked account, which the supplier cannot access automatically. However, the scope is limited to the specified recipients and we believe that it does not interfere with the observation period.

Institutional information is accessible over the following websites: https://taxbackinternational.com/blog/italy-spesometro-esterometro-reports/ and https://www.avalara.com/vatlive/en/country-guides/europe/italy/italian-spesometro-declaration.html. Both accessed 7 July 2023.

Decree of the president of the council of ministers on 27 Feb 2019: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2019/03/05/19A01521/sg.

Due to data availability, we restrict the set of control variables to EURO and THRESHOLD GAP.

We estimate boundaries based on both, exports and imports to capture all variations that could lead to a lower TDG.

In this case, we use the first two or four digits from the 8-digit product code. We are aware of further matching procedures like propensity score matching or entropy balancing. However, these procedures rely on the identification of matches (in this case matched treatment and control products) based on a set of characteristics that have an effect on the assignment to treatment or control group and the outcome variable. Those (product specific) characteristics are unobservable which is why we refrain from these procedures and create adequate workarounds.

Next to the assumed higher comparability, the finding could reveal a possible spillover effect that is reversed by e-invoicing. The earlier introduction of RCM on fraud-prone products might have caused fraudsters to use other but comparable products. Fraudsters switched to other products of the same product category rather than to a complete different product group since they may have installed an effective supply chain including exporters, fraudsters and other involved firms. Under the premise that e-invoicing reduces fraud, we consequently observe stronger effects with these fraud-prone products. However, our model cannot detect any previous spillovers on these similar treatment products. Therefore, our hypothesis is mostly opinion based and has to be taken with caution.

The dependent variable is the natural logarithm of the trade data gap (\(\mathrm{ln \,TDG}\)), defined as the natural logarithm of exports over imports. Hence, we use the reverse operation \({e}^{\delta }\) to calculate the effects in percentage.

We estimate Eqs. (4) and (5) using all given decimal places by Stata for the coefficients on the interaction term that is − 0.0556129 and − 0.0483151 for \({\delta }_{{\text{weighted}}}\) using export share weights and import share weights, respectively. However, we obtain a quantitatively similar range of \({\text{REVLOSS}}\) between € 2.2 and € 2.6 billion using the 2018 mean of exports (imports) that is an average monthly value of exports (imports) of a certain product from a certain exporting country and multiplying this with the mean value of country pair-product observations (panel ID variable), the mean VAT rate and \({\delta }_{{\text{weighted}}}\) times 12. Multiplying by 12 months leads to a yearly amount based on the average monthly values. In an earlier version of this paper, we calculated € 0.6 billion to € 1.0 billion as the VAT fraud tackled by the reform. However, this figure was based on country-specific estimates that did not take non-significant results into account (see Table 16 in Appendix).

We use a mid-point estimate between € 2.2 and 2.6 billion and divide this by the VAT gap of € 32.415 billion.

While the Italian Ministry of Economy and Finance (2018a) states that the running costs of the system are about € 10 million a year, a white paper from May 2021 by the Italian Revenue Agency (2021) states an amount of € 20 million. In this document, € 2.5 million is allocated to the initial set-up costs regarding B2G invoicing in 2015 and additional € 1.2 million to extent the system to B2B and B2C invoicing.

Council Directive 2006/112/EC of November 28, 2006, on the common system of value-added tax.

We initially excluded fuels from the sample since they were already covered by the e-invoicing obligation six months before the general introduction. However, we further refuse from using fuels as a further control due to the very low number of observations and products covered by this initial roll-out.

For example, the first digit equals to 7 regarding the 8-digit product code “71089080.” Therefore, we construct 10 different groups from 0 to 9 within our dataset. See also Table 7 for the distribution and explanations on these products.

References

Ainsworth, R. T. (2006). Carousel fraud in the EU: A digital vat solution. Tax Notes International, p. 443. Boston Univ. School of Law Working Paper No. 06–23.

Alonso, C., Feliz, L., Gil, P., & Pecho, M. (2021). Enhancing tax compliance in the Dominican Republic through risk-based VAT invoice management. IMF Working Paper 2021.231, Washington.

Backer, A. C., Larcker, D. F., & Wang, C. C. Y. (2022). How much should we trust staggered difference-in-differences estimates? Journal of Financial Economics, 144(2), 370–395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2022.01.004

Barreix, A., & Zambrano, R. (2018). Electronic invoicing in Latin America: Process and challenges. In A. Barreix, R. Zambrano (Eds.), Electronic invoicing in Latin America, (pp. 4–46). https://publications.iadb.org/publications/english/document/Electronic-Invoicing-in-Latin-America.pdf. Accessed 17 Aug 2022.

Bellon, M., Dabla-Norris, E., Khalid, S., & Lima, F. (2022). Digitalization to improve tax compliance: Evidence from VAT e-invoicing in Peru. Journal of Public Economics. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2022.104661

Bérgolo, M., Ceni, R., & Sauval, M. (2018). Factura electrónica y cumplimiento tributario: Evidencia a partir de un enfoque cuasi-experimental. Inter-American Development Bank. https://publications.iadb.org/es/factura-electronica-y-cumplimiento-tributario-evidencia-partir-de-un-enfoque-cuasi-experimental. Accessed 17 Aug 2022.

Braml, M. T., & Felbermayr, G. J. (2021). The EU self-surplus puzzle: An indication of VAT fraud? International Tax and Public Finance. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-021-09713-x

Buettner, T., & Tassi, A. (2023). VAT fraud and reverse charge: Empirical evidence from VAT return data. International Tax and Public Finance, 30, 849–878. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-023-09776-y

Bussy, A. (2020). Cross-border value added tax fraud in the European Union. Working paper. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3569914. Accessed 17 Aug 2022.

Cnossen, S. (1998). Global trends and issues in value added taxation. International Tax and Public Finance, 5, 399–428.

European Commission (2016). European commission–fact sheet, action plan on VAT: Questions and answers. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/MEMO_16_1024. Accessed 17 Aug 2022.

European Commission. (2020). Communication from the commission to the European parliament and the council, an action plan for fair and simple taxation supporting the recovery strategy, COM (2020) 312 final from 15.7.2020.

European Commission. (2021). Proposal for a council implementing decision amending implementing decision (EU) 2018/593 as regards the duration and scope of the derogation from articles 218 and 232 of directive 2006/112/EC, COM(2021) 681 final from 05.11.2021.

European Council (2018). Council implementing decision (EU) 2018/593 of 16 April 2018 authorising the Italian Republic to introduce a special measure derogating from articles 218 and 232 of directive 2006/112/EC on the common system of value added tax, OJ EU 2018, No L 99/14.

European Court of Auditors (2019). Fighting fraud in EU spending: action needed. Special Report No 01 2019. https://op.europa.eu/webpub/eca/special-reports/fraud-1-2019/en/. Accessed 6 July 2023.

Eurostat (2017). National requirements for the intrastat system 2018 edition. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3859598/8512202/KS-07-17-102-EN-N.pdf/736c4a50-c240-4144-b087-4fa6aece8ee0. Accessed 13 July 2023.

Eurostat (2020). International trade in goods (ext_go_agg). https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/cache/metadata/de/ext_go_agg_esms.htm. Accessed 17 Aug 2022.

Eurostat (2021). National requirements for the Intrastat system 2021 edition. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3859598/12889594/KS-GQ-21-011-EN-N.pdf/4ffbf688-0ffa-5223-f7a5-c784d3873750?t=1624005514521. Accessed 27 July 2023.

Fan, H., Liu, Y., Qian, N., & Wen, J. (2020). Computerizing VAT invoices in China. National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w24414

Fisman, R., & Wei, S.-J. (2004). Tax rates and tax evasion: Evidence from “missing imports” in China. Journal of Political Economy, 112(2), 471–496.

Frunza, M. (2016). Cost of the MTIC VAT fraud for European Union members. Working Paper. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2758566. Accessed 17 Aug 2022.

Giannotti, E., Luchetta, G., & Poniatowski, G. (2019). Study the evaluation of the invoicing rules of Directive 2006/112/EC. Final Report. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.2778/771345.

Hernandez, K., & Robalino, J. (2018). Evidence of the impact of electronic invoicing of taxes in Latin America. In A. Barreix, R. Zambrano (Eds.), Electronic invoicing in Latin America (pp. 47–62). https://publications.iadb.org/publications/english/document/Electronic-Invoicing-in-Latin-America.pdf. Accessed 17 Aug 2022.

Italian Revenue Agency (2017). Simplification measures of taxpayers' communication obligations in relation to lists summaries of intra-community transactions (so-called "Intrastat") Implementation of article 50, paragraph 6, of the decree-law of 30 August 1993, n. 331, as modified by the art. 13, paragraph 4-quater, of the decree-law of 30 December 2016, n. 244, converted, with amendments, by law 27 February 2017, n. 19. Prot. n. 194409/2017. https://www.adm.gov.it/portale/documents/20182/883891/PROVVEDIMENTO%2BN_194409_del_25092017.pdf/97be4d27-0270-4ea0-88c4-b64244f1da92?t=1506495963251. Accessed 13 July 2023

Italian Ministry of Economy and Finance [Ministero dell´Economia e delle Finanze] (2018a). eInvoicing in Italy: Pioneering in mandate B2B eInvoicing. Brussels. https://documents.pub/document/einvoicing-in-italy-20181204-a-jan-2017-obligation-for-all-vat-taxable.html. Accessed 17 Aug 2022.

Italian Ministry of Economy and Finance (2018b). Relazione sull’economia non osservata e sull’evasione fiscale e contributiva anno 2018. https://www.dt.mef.gov.it/export/sites/sitodt/modules/documenti_it/analisi_progammazione/documenti_programmatici/def_2018/A6_-_Relazione_evasione_fiscale_e_contributiva.pdf. Accessed 27 June 2023.

Italian Ministry of Economy and Finance (2020). Relazione sull’economia non osservata e sull’evasione fiscale e contributiva anno 2020. https://www.finanze.it/export/sites/finanze/.galleries/Documenti/Varie/Relazione_evasione_fiscale_e_contributiva_-Allegato-_NADEF_2020.pdf. Accessed 30 June 2023.

Italian Revenue Agency (2021). Electronic invoicing in Italy. White paper. May 2021. https://www.oecd.org/tax/forum-on-tax-administration/publications-and-products/Italy-Electronic-invoicing-May-2021.pdf. Accessed 4 July 2023.

Jacobs, B. (2017). Digitalization and taxation. In S. Gupta, M. Keen, A. Shah, & G. Verdier (Eds.), Digital revolutions in public finance (pp. 25–55). International Monetary Fund. https://doi.org/10.5089/9781484315224.071

Javorcik, B., & Narciso, G. (2008). Differentiated products and evasion of import tariffs. Journal of International Economics, 76(2), 208–222.

Javorcik, B., & Narciso, G. (2017). WTO accession and tariff evasion. Journal of Development Economics, 125, 59–71.

Kitsios, E., Tovar Jalles, J., & Verdier, G. (2022). Tax evasion from cross-border fraud: does digitalization make a difference? Applied Economics Letters. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2022.2056566

Lee, H. C. (2016). Can electronic tax invoicing improve tax compliance? A case study of the Republic of Korea’s electronic tax invoicing for value-added tax. World Bank policy research working paper series 7592. http://hdl.handle.net/10986/23931. Accessed 17 Aug 2022.

Loschky, A. (2006). Asymmetries in foreign trade statistics. [Asymmetrien in der Außenhandelsstatistik]. Wirtschaft und Statistik, March 2006, 257–263.

Mascagni, G., Mengistu, A. T., & Woldeyes, F. B. (2021). Can ICTs increase tax compliance? Evidence on taxpayer responses to technological innovation in Ethiopia. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 189, 172–193.

McLure, C. E. (1993). Economic, administrative, and political factors in choosing a general consumption tax. National Tax Journal, 46(3), 345–358.

Mishra, P., Subramanian, A., & Topalova, P. (2008). Tariffs, enforcement, and customs evasion: Evidence from India. Journal of Public Economics, 92(10–11), 1907–1925.

OECD. (2020). Consumption tax trends 2020: VAT/GST and excise rates: Trends and policy issues. Advance Online Publication. https://doi.org/10.1787/152def2d-en

Poniatowski, G., Bonch-Osmolovskiy, M., & Śmietanka, A. (2020). Study and reports on the VAT gap in the EU-28 member states: 2020 final report. https://data.europa.eu/doi/https://doi.org/10.2778/2517. Accessed 17 Aug 2022.

Poniatowski, G., Bonch-Osmolovskiy, M., & Śmietanka, A. (2022). VAT gap in the EU: Report 2022. https://data.europa.eu/doi/https://doi.org/10.2778/109823. Accessed 27 July 2023.

Ramirez, J., Oliva, N., & Andino, M. (2018). Facturacion Electronica en Ecuador: Evaluacion de impacto en el cumplimiento tributario. Inter-American Development Bank. https://publications.iadb.org/es/facturacion-electronica-en-ecuador-evaluacion-de-impacto-en-el-cumplimiento-tributario. Accessed 17 Aug 2022.

Sergiou, L. (2012). Value added tax (VAT) carousel fraud in the European Union. The Journal of Accounting and Management, 2(2), 9–21.

Stiller, W., & Heinemann, M. (2019). Reverse-charge-mechanism – an effective method against VAT fraud in Germany and Austria? [Reverse-Charge-Verfahren – Eine wirkungsvolle Maßnahme gegen den Umsatzsteuerbetrug in Deutschland und Österreich?]. Betriebswirtschaftliche Forschung und Praxis, 72(2), 177–193.

Stiller, W., & Heinemann, M. (2023). Do more harm than good? The optional reverse charge mechanism against VAT fraud. Working paper. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.13802.44482. Accessed 7 Aug 2023.

Stoyanov, A. (2012). Tariff evasion and rules of origin violations under the Canada–U.S. free trade agreement. Canadian Journal of Economics, 45(3), 879–902.

Strango, C. (2021). Does digitalisation in public services reduce tax evasion? The Economic Research Guardian, 11(2), 221–235.

Templado, I., & Artana, D. (2018). Analisis del impacto de la Factura Electronica en la Argentina. Inter-American Development Bank. https://publications.iadb.org/publications/spanish/document/An%C3%A1lisis-del-impacto-de-la-factura-electr%C3%B3nica-en-Argentina.pdf. Accessed 17 Aug 2022.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank three anonymous reviewers, Natalie Packham and the participants at the Jill McKinnon Research Seminar 2023 at the Macquarie University in Sydney, CESifo Area Conference on the Economics of Digitization 2022 in Munich, AMEF 2022 in Thessaloniki and EAA 2022 in Bergen for valuable comments.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A

See Table 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15.

Appendix B: Heterogeneity analysis

The following section provides additional tests that aim to explore the heterogeneity of the reform. We perform various splits of the sample and adapt our regression model to uncover the effect of e-invoicing more in detail.

2.1 Estimates by exporting country

In this first heterogeneity test, we estimate our baseline regression model separately by each exporting country. It appears that the effect is not homogenous over all exporting Member States. E-invoicing seems to have a statistically significant impact on \({\text{ln TDG}}\) when Estonia, Greece, Hungary or Slovakia is the exporting country. However, \({\text{ln TDG}}\) even increases in case of Estonia. In 17 out of 27 cases, the interaction coefficient is negative, indicating that in the majority of cases the TDG decreases (Table 16).

2.2 Different susceptibility to fraud

In this second heterogeneity test, we aim to identify products that were most affected by e-invoicing to check if certain products drive the results. We separate products within the treatment group that could potentially be more affected by fraud prior to mandatory e-invoicing and refer to them as RCM POTENTIAL. This group includes products that could theoretically fall under RCM according to the VAT Directive,Footnote 34 but Italy has not (yet) decided to introduce this mechanism on these products (for an overview of RCM applications see Table 9, Appendix). The Council of the European Union classifies fraud-sensitive products as a potential scope of the RCM. However, the lack of inclusion in the RCM could indicate that Italy does not identify fraud within the particular product group. Therefore, the expected relationship is unclear and needs to be tested. An explanation on the product groups is presented in Table 19 (Appendix).Footnote 35

We make use of our baseline model from Eq. (2); however, we split the treatment group into two separate groups (RCM POTENTIAL and OTHER; see Table 19). According to the baseline approach, the RCM products form the control group. Referring to the descriptive statistics displayed in Panel A of Table 20, it appears that both product groups show a considerably high mean \({\text{ln TDG}}\) before e-invoicing. Before the reform, the \({\text{ln TDG}}\) of 0.2805 for RCM POTENTIAL is only slightly higher than for OTHER (0.2561). This suggests comparable fraud levels pre-reform. The average \({\text{ln TDG}}\) for RCM POTENTIAL is lower after the reform, at 0.1371, however, remains considerably greater than zero. The mean \({\text{ln TDG}}\) for OTHER shows the most significant reduction along the reform, from 0.2561 to 0.0451.