Abstract

Background

Previous studies showed that patients with Severe IBS respond better to fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) than do those with Moderate IBS.

Aims

The present study aimed to determine the effects of the transplant dose, route of administering it and repeating FMT on this difference.

Methods

This study included 186 patients with IBS randomized 1:1:1 into groups with a 90-g transplant administered once to the colon (LI), once to the duodenum (SI), or twice to the distal duodenum twice (repeated SI). The patients provided a fecal sample and were asked to complete three questionnaires at baseline and at 3, 6, and 12 months after FMT. The fecal bacteria composition and Dysbiosis index were analyzed using 16 S rRNA gene PCR DNA amplification/probe hybridization covering regions V3–V9.

Results

There was no difference in the response rates between severe IBS and moderate IBS for SI and repeated SI at all observation intervals after FMT. In the LI group, the response rate at 3 months after FMT was higher for moderate IBS than for severe IBS. The levels of Dorea spp. were higher and those of Streptococcus salivarius subsp. Thermophilus, Alistipes spp., Bacteroides and Prevotella spp., Parabacteroides johnsoni and Parabacteroides spp. were lower in moderate IBS than in severe IBS.

Conclusions

There was no difference in the response to FMT between severe and moderate IBS when a 90-g transplant was administered to the small intestine. The difference in the bacterial profile between severe and moderate IBS may explain the difference in symptoms between these patients. (www.clinicaltrials.gov: NCT04236843).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a chronic common condition involving gut–brain interactions that affects about 10% of the global population [1]. The prevalence of IBS varies between different geographical regions, being highest in South America, Africa and southern Europe (15–20%), lowest in Southeast Asia and the Middle East (about 7%), and intermediate in North America, northern Europe and Australia (11.8–14%) [1]. IBS markedly reduces the quality of life of affected patients and imposes huge direct (healthcare costs) and indirect (reduced working ability) economic costs on society [1]. There is no effective treatment for IBS, with only symptomatic clinical treatments being applied.

The etiology of IBS is not known, but the gut microbiota and bacterial diversity appear to play major roles in its pathophysiology [2]. Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) to treat IBS has been tested in several randomized controlled trials (RCTs), which have found that its efficacy seems to vary with the protocol used [3]. One of these RCTs that applied a protocol with a combination of favorable factors found that FMT was highly effective and provided durable effects for up to 3 years [4,5,6].

While FMT appears to be a promising treatment for IBS, concerns have been raised about its safety [7]. These worries were triggered by two patients developing bacteremia with an antibiotic-resistant Escherichia coli strain following FMT, resulting in one fatality [8, 9]. Mild and self-limiting adverse events have also been reported in the days following FMT for IBS [4,5,6]. However, serious long-term adverse events are feared when using FMT to treat IBS, which is a benign condition occurring in young people. Furthermore, a recently reported RCT with a high efficacy included a cohort of patients with refractory IBS [10]. In addition, patients with severe IBS symptoms respond better to FMT than do those with moderate symptoms, with this difference in response lasting for up to 3 years [11]. These findings suggest that FMT should be restricted to those with severe IBS.

Studies have shown that patients with severe IBS symptoms respond better to FMT than do those with moderate IBS symptoms when the transplant is administered to the small intestine [10, 11]. The present study aimed at determining whether the effects of increasing the fecal dose of the transplant, repeating FMT and administering the fecal transplant to the large intestine would affect the differences in how patients with severe and moderate IBS symptoms respond to FMT.

Methods

Study Design and Randomization of Patients

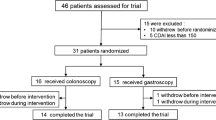

The study design and randomization are described in detail elsewhere [12]. In brief, the patients provided a fecal sample and were asked to complete three questionnaires at baseline and at 3, 6, and 12 months after FMT. Polyethylene glycol and loperamide were allowed during the intervention as rescue medications. The patients were randomized 1:1:1 in blocks of six to receiving 90 g of donor feces administered once to the cecum of the colon (LI), once to the distal duodenum (SI), or twice to the distal duodenum with a 1-week interval (repeated SI).

Patients

The patients are also described in detail elsewhere [12]. The present study included 186 patients who fulfilled the Rome IV criteria for IBS. The medical history was obtained and a physical examination and blood tests were performed to exclude other diseases. The baseline characteristics of the included patients are given in Table 1.

The inclusion criteria were age > 18 years and having moderate-to-severe IBS symptoms, as indicated by a total score on the IBS Severity Scoring System (IBS-SSS) of ≥175. The exclusion criteria were the presence of systemic disease, pregnancy or planning pregnancy, lactating, abdominal surgery (with the exception of appendectomy, cholecystectomy, caesarean section and hysterectomy), or immune deficiency, taking immune-modulating medication, having severe psychiatric disorders, alcohol or drug abuse, or using probiotic, antibiotic or IBS medication within 8 weeks prior to the start of the study.

Donor

The superdonor used in the study was the same person used in our previous study [4]. Briefly, he was a healthy Caucasian 40-year-old male with a normal BMI who had been born via a vaginal delivery and breastfed. He was non-smoker, was not taking any medication regularly and had taken only a few courses of antibiotics during his lifetime. He exercised regularly and took sport-specific dietary supplements, which made his diet richer than average in protein, fiber, minerals and vitamins. He was screened according to the European guidelines for FMT donors [13]. He was vaccinated against COVID-19 and tested weekly for COVID-19 during the period in which he donated his feces. His fecal bacterial composition was tested regularly, which revealed that his bacterial profile was stable during the trial period.

Fecal Sample Collection, Preparation and Administration

The methods used to collect and prepare feces as well as to administer the fecal transplant have been described in detail previously [4]. Briefly, fecal samples from the donor and patients were immediately frozen and kept at − 20 °C until they were delivered to the laboratory, where they were stored at − 80 °C. Feces were thawed for 2 days at 4 °C, and then a 90-g sample was mixed manually with 90 mL of sterile saline. The fecal transplant was administered to the colon cecum after bowel preparation via the working channel of a colonoscope in the LI group, and to the distal duodenum after overnight fasting via the working channel of a gastroscope in the SI and repeated-SI groups.

Symptoms and Quality-of-Life Assessment

Symptoms were assessed using the IBS-SSS and the Fatigue Assessment Scale (FAS) questionnaires [14, 15].

The responders were patients whose IBS-SSS total score decreased by ≥ 50 points after FMT. Quality of life was measured using the IBS Quality of Life (IBS-QoL) questionnaire [16, 17].

Bacteria Analysis

Fecal bacterial compositions and dysbiosis indexes (DIs) were analyzed using the GA-map® Dysbiosis Test. This test uses 16 S rRNA gene PCR DNA amplification/probe hybridization covering regions V3–V9 followed by DNA probe hybridization of 48 bacterial markers as described previously in detail [18]. The DI was measured on a five-point scale, where values of 1 and 2 indicated normobiosis, and those of 3–5 indicated dysbiosis.

Adverse Events and Medication

The patients were asked to record their bowel habits, any adverse events, and the use of rescue medications or other new medications in a diary.

Statistical Analysis

The differences in response, proportions of IBS patients with different IBS symptom severities or complete remission, sex, IBS subtypes and used medication were assessed using Fisher’s exact test. Differences in the IBS-SSS, FAS and IBS-QoL scores, DI, and bacterial fluorescence signals between patients with severe and moderate IBS were analyzed using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test.

Ethics

The study was approved by the West Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics, Bergen, Norway (approval no. 2019/6841/REK vest). This study was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (no. NCT04236843).

Results

Responses of Patients to FMT

Three patients dropped out: one at 3 months, one at 6 months and one at 12 months after FMT. Two additional patients were excluded because of pregnancy at 3 and 12 months after FMT.

The response rates did not differ between patients with severe IBS and moderate IBS symptoms in the SI and repeated-SI groups at all observation intervals after FMT (Fig. 1). In the LI group, patients with moderate IBS symptoms had higher response rates than did those with severe IBS symptoms at 3 months after FMT, but not at 6 and 12 months after FMT. The proportion of patients with severe IBS symptoms decreased significantly while those of patients with moderate IBS symptoms, mild IBS symptoms and remission increased in all treatment groups at all observation times after FMT (Table 2). Similarly, the proportion of patients with moderate IBS symptoms decreased and the proportion of patients with mild IBS symptoms and remission increased in all treatment groups at all observation times after FMT (Table 3).

Symptoms and Quality of Life

The IBS-SSS total scores were higher in patients with severe IBS symptoms than in those with moderate IBS symptoms at baseline, and remained higher after FMT in all treatment groups (Fig. 2). However, the difference in the IBS-SSS total scores between patients with severe and moderate IBS symptoms was reduced at 3 months after FMT in both the SI and repeated-SI groups, and at 6 months after FMT in the LI group. The FAS total scores were higher in patients with severe IBS symptoms than in those with moderate IBS symptoms in the SI and repeated-SI groups at baseline (Fig. 3). After FMT, there were no differences between patients with severe and moderate IBS symptoms in all treatment groups at all observation intervals (Fig. 3).

In the LI group, there was no difference between patients with severe and moderate IBS symptoms in the total scores of IBS-QoL at baseline or after FMT at all observation times (Fig. 4). In the SI group, the IBS-QoL total scores were lower in patients with severe IBS than in those with moderate IBS symptoms at baseline and at 3 months after FMT (Fig. 4). However, these scores did not differ between patients with severe and moderate IBS symptoms at 6 and 12 months. In the repeated-SI group, the IBS-QoL total scores were lower in patients with severe IBS symptoms than in those with moderate IBS symptoms at baseline and at 6 and 12 months after FMT, but not at 3 months after FMT.

Bacteria Analysis

At baseline, the DI was lower in patients with severe IBS symptoms than in those with moderate IBS symptoms in the repeated-SI group but not in the LI and SI groups (Fig. 5). The DI did not differ between patients with severe and moderate IBS symptoms at all observation times after FMT in all treatment groups.

At baseline, the fluorescence signals of Dorea spp. were higher and those of Streptococcus salivarius subsp. thermophilus were lower in patients with moderate IBS symptoms than in those with severe symptoms (Supplementary Table 1). At 3 months after FMT, there were no differences in the fluorescence signals of all bacteria examined between patients with severe and moderate IBS symptoms (Supplementary Table 2). At 6 months after FMT, the fluorescence signals of Streptococcus salivarius subsp. thermophilus were lower in patients with moderate IBS symptoms than in those with severe IBS symptoms (Supplementary Table 3). At 12 months after FMT, the fluorescence signals of Alistipes spp., Bacteroides spp., Prevotella spp., Parabacteroides johnsonii and other Parabacteroides spp. were lower in patients with moderate IBS symptoms than in those with severe IBS symptoms (Supplementary Table 4).

Adverse Events and Medication

The adverse events and medication taken have been described in detail previously. Briefly, mild and self-limiting adverse events occurred in the first days after FMT in the form of nausea (9%), abdominal pain (14%), diarrhea (16%) and constipation (20%).

Eleven of the non-responders took rescue medication: polyethylene glycol (n = 6) and loperamide (n = 5). Two of the responders took loperamide: one only once and the other regularly.

Discussion

This study found no difference in the response rates to FMT between patients with severe and moderate IBS symptoms. This finding contrasts with previous observations that patients with severe IBS symptoms responded better to FMT than did those with mild IBS symptoms [4,5,6]. A 90-g fecal transplant was used in the present study, whereas these previous studies used 30- and 60-g transplants [4,5,6]. It is therefore reasonable to conclude that the absence of difference in the response to FMT between patients with severe and moderate IBS symptoms is at least partially due to the higher fecal transplant dose used in the present study. The route of administering the fecal transplant also seems to play a role in the difference in the response to FMT between these two groups of IBS patients. The response rate to FMT was higher in patients with moderate IBS symptoms than in those with severe IBS symptoms at 3 months after FMT when the fecal transplant was administered to the large intestine. On the other hand, administering the fecal transplant to the small intestine resulted in no difference between these two groups of IBS patients at all observation times after FMT. Repeating FMT appeared to have no additional effect compared with single FMT regarding this difference.

At baseline, the fluorescence signals of Dorea spp. were higher in IBS patients with moderate IBS than those with severe IBS. Dorea spp. are Gram-positive and non-spore-forming bacteria that produce acetic acid and associated with diabetes [19]. At baseline and at 6 months after FMT, the fluorescence signals of Streptococcus salivarius subsp. thermophilus were lower in patients with moderate IBS symptoms than in those with severe symptoms. Streptococcus salivarius subsp. thermophilus is a Gram-positive, coccus-shaped, facultative anaerobic bacterium [20] that secretes β-galactosidase, which inhibits tumorigenesis and exerts anti-inflammatory effects via NF-κB pathway activation [20,21,22], The fecal levels of Streptococcus salivarius subsp. thermophilus in IBS patients were reported to be positively correlated with both IBS symptoms and fatigue [5]. At 12 months after FMT, the fluorescence signals of Alistipes spp., Bacteroides spp., Prevotella spp. and Parabacteroides johnsonii were lower in patients with moderate IBS symptoms than in those with severe IBS symptoms. Alistipes spp. are Gram-negative, rod-shaped, anaerobic, non-spore-forming and bile-resistant bacteria [23,24,25]. These bacteria produce short-chain fatty acids with anti-inflammatory effects such as acetic, succinic and propionic acids [26, 27] and they also express methylmalonyl-CoA epimerase, the gene for which is located on an operon of the acetyl-CoA carboxylase gene [26]. Moreover, Alistipes spp. hydrolyze tryptophan, which is a precursor for serotonin, to produce indole [26]. Prevotella spp. are Gram-negative, anaerobic, rod-shaped common commensal bacteria [28]. Parabacteroides johnsonii is a Gram-negative, anaerobic, non-spore-forming and rod-shaped bacterium [29,30,31]. The fecal levels of Alistipes spp., Prevotella spp. and Parabacteroides johnsonii were inversely correlated with the total scores on both the IBS-SSS and FAS [6, 12]. These findings may explain the difference in the symptom severity between patients with moderate and severe IBS symptoms.

This study has shown that IBS patients with either severe or moderate IBS symptoms benefit from FMT when a high dose of fecal transplant is administered to the small intestine. FMT as a treatment for IBS had mild and self-limiting short-term adverse events, with no other adverse events reported after 3 years of follow-up [4,5,6]. A follow-up after about 3 years of patients who received FMT due to Clostridioides difficile infection after also did not reveal any long-term adverse events [32]. It can therefore be concluded that the available data support that FMT is a safe intervention that can be offered to IBS patients regardless of their symptom severity.

The main strengths of this study were that it included a large cohort of both female and male patients with IBS comprising three IBS subtypes, and used a single well-defined superdonor. However, the limitations of this study were that it did not include the fourth IBS subtype (IBS-U) and did not investigate the entire bacterial composition of intestinal tract.

In conclusion, patients with severe and moderate IBS symptoms respond similarly to FMT when a 90-g fecal transplant is administered to the small intestine. The available data show that FMT is a safe intervention that can be offered to IBS patients regardless of their symptom severity.

Data availability

Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Black CJ, Ford AC. Global burden of irritable bowel syndrome: trends, predictions and risk factors. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17(8):473–486.

El-Salhy M, Hatlebakk JG, Hausken T. Diet in Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS): Interaction with Gut Microbiota and Gut Hormones. Nutrients. 2019;11(8):1824.

El-Salhy M, Hausken T, Hatlebakk JG. Current status of fecal microbiota transplantation for irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;33(11):e14157.

El-Salhy M, Hatlebakk JG, Gilja OH, et al. Efficacy of faecal microbiota transplantation for patients with irritable bowel syndrome in a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Gut. 2020;69(5):859–867.

El-Salhy M, Winkel R, Casen C, et al. Efficacy of fecal microbiota transplantation for patients with irritable bowel syndrome at three years after transplantation. Gastroenterology. 2022;163(4):962–994.e14.

El-Salhy M, Kristoffersen AB, Valeur J, et al. Long-term effects of fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;34(1):e14200.

Camilleri M. FMT in IBS: a call for caution. Gut. 2021;70(2):431.

DeFilipp Z, Bloom PP, Torres Soto M, et al. Drug-Resistant E. coli Bacteremia Transmitted by Fecal Microbiota Transplant. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(21):2043–2050.

Blaser MJ. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation for Dysbiosis - Predictable Risks. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(21):2064–2066.

Holvoet T, Joossens M, Vázquez-Castellanos JF, et al. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Reduces Symptoms in Some Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome With Predominant Abdominal Bloating: Short- and Long-term Results From a Placebo-Controlled Randomized Trial. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(1):145–157.e8.

El-Salhy M, Mazzawi T, Hausken T, et al. The fecal microbiota transplantation response differs between patients with severe and moderate irritable bowel symptoms. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2022;57(9):1036–1045.

El-Salhy M, Gilja OH, Hatlebakk JG. Factors affecting the outcome of fecal microbiota transplantation for patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2023 Jul 10:e14641.

Cammarota G, Ianiro G, Tilg H, et al. European consensus conference on faecal microbiota transplantation in clinical practice. Gut 2017;66(4):569–580.

Francis CY, Morris J, Whorwell PJ. The irritable bowel severity scoring system: a simple method of monitoring irritable bowel syndrome and its progress. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11(2):395–402.

Hendriks C, Drent M, Elfferich M, et al. The Fatigue Assessment Scale: quality and availability in sarcoidosis and other diseases. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2018;24(5):495–503.

Drossman DA, Patrick DL, Whitehead WE, et al. Further validation of the IBS-QOL: a disease-specific quality-of-life questionnaire. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(4):999–1007.

Drossman DA, Camilleri M, Mayer EA, et al. AGA technical review on irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2002;123(5):2108–2131.

Casén C, Vebø HC, Sekelja M, et al. Deviations in human gut microbiota: a novel diagnostic test for determining dysbiosis in patients with IBS or IBD. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42(1):71–83.

Palmnäs-Bédard MSA, Costabile G, Vetrani C, et al. The human gut microbiota and glucose metabolism: a scoping review of key bacteria and the potential role of SCFAs. Am J Clin Nutr. 2022;116(4):862–874.

Martinović A, Cocuzzi R, Arioli S, et al. Streptococcus thermophilus: To Survive, or Not to Survive the Gastrointestinal Tract, That Is the Question! Nutrients. 2020;12(8):2175.

Li Q, Hu W, Liu WX, et al. Streptococcus thermophilus Inhibits Colorectal Tumorigenesis Through Secreting β-Galactosidase. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(4):1179–1193.e14.

Kaci G, Goudercourt D, Dennin V, et al. Anti-inflammatory properties of Streptococcus salivarius, a commensal bacterium of the oral cavity and digestive tract. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80(3):928–934.

Rautio M, Eerola E, Väisänen-Tunkelrott ML, et al. Reclassification of Bacteroides putredinis (Weinberg et al., 1937) in a new genus Alistipes gen. nov., as Alistipes putredinis comb. nov., and description of Alistipes finegoldii sp. nov., from human sources. Syst Appl Microbiol 2003;26(2):182–188.

Mishra AK, Gimenez G, Lagier JC, et al. Genome sequence and description of Alistipes senegalensis sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci. 2012;6(3):1–16.

Mavromatis K, Stackebrandt E, Munk C, et al. Complete genome sequence of the bile-resistant pigment-producing anaerobe Alistipes finegoldii type strain (AHN2437(T)). Stand Genomic Sci. 2013;8(1):26–36.

Parker BJ, Wearsch PA, Veloo ACM, et al. The Genus Alistipes: Gut Bacteria With Emerging Implications to Inflammation, Cancer, and Mental Health. Front Immunol. 2020;11:906.

Oliphant K, Allen-Vercoe E. Macronutrient metabolism by the human gut microbiome: major fermentation by-products and their impact on host health. Microbiome. 2019;7(1):91.

Liou JS, Huang CH, Ikeyama N, et al. Prevotella hominis sp. nov., isolated from human faeces. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2020;70(8):4767–4773.

Ezeji JC, Sarikonda DK, Hopperton A, et al. Parabacteroides distasonis: intriguing aerotolerant gut anaerobe with emerging antimicrobial resistance and pathogenic and probiotic roles in human health. Gut Microbes. 2021;13(1):1922241.

Sakamoto M, Kitahara M, Benno Y. Parabacteroides johnsonii sp. nov., isolated from human faeces. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2007;57(Pt 2):293–296.

Noor SO, Ridgway K, Scovell L, et al. Ulcerative colitis and irritable bowel patients exhibit distinct abnormalities of the gut microbiota. BMC Gastroenterol. 2010;10:134.

Perler BK, Chen B, Phelps E, et al. Long-Term Efficacy and Safety of Fecal Microbiota Transplantation for Treatment of Recurrent Clostridioides difficile Infection. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2020;54(8):701–706.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Bergen (incl Haukeland University Hospital)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.E.S. designed the study, obtained the funding, administered the study, recruited and followed up the patients, performed FMT, collected, analyzed, and interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript. J.G.H. contributed to designing the study and to data analysis and interpretation, and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Grant support

Helse Fonna (grant no. 40415). Helse Vest (grant no. F-12854-D10636).

Disclosure

M.E.S and JGH have nothing to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

El-Salhy, M., Hatlebakk, J. Factors Underlying the Difference in Response to Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Between IBS Patients with Severe and Moderate Symptoms. Dig Dis Sci 69, 1336–1344 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-024-08369-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-024-08369-x