Abstract

Needs assessment in mental health is a complex and multifaceted process that involves different steps, from assessing mental health needs at the population or individual level to assessing the different needs of individuals or groups of people. This review focuses on quantitative needs assessment tools for people with mental health problems. Our aim was to find all possible tools that can be used to assess different needs within different populations, according to their diverse uses. A comprehensive literature search with the Boolean operators “Mental health” AND “Needs assessment” was conducted in the PubMed and PsychINFO electronic databases. The search was performed with the inclusion of all results without time or other limits. Only papers addressing quantitative studies on needs assessment in people with mental health problems were included. Additional articles were added through a review of previous review articles that focused on a narrower range of such needs and their assessment. Twenty-nine different need-assessment tools specifically designed for people with mental health problems were found. Some tools can only be used by professionals, some by patients, some even by caregivers, or a combination of all three. Within each recognized tool, there are different fields of needs, so they can be used for different purposes within the needs assessment process, according to the final research or clinical aims. The added value of this review is that the retrieved tools can be used for assessment at the individual level, research purposes or evaluation at the outcome level. Therefore, best needs assessment tool can be chosen based on the specific goals or focus of the related needs assessment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Mental disorders are the largest contributor to the disease burden in Europe (Wykes et al., 2021), and mortality related to such conditions increases the overall economic burden (McGorry & Hamilton, 2016). Mental disorders affect various life domains, from physical health to daily living, friends, family situations, and education, and are associated with greater unemployment and economic problems (Wykes et al., 2021).

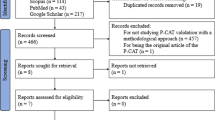

In order to plan and carry out successful mental health care, it is necessary to have a good mental health information system that also includes data about related needs (Wykes et al., 2021). When a need is identified, an action can be (re)organized to address it. Such action, based on the needs identified by the affected individuals, professionals or society, results in either satisfaction or dissatisfaction if the needs continue to be present (Endacott, 1997). Assessing needs might also be used to assess the adequacy and prioritization of mental health services at the population level (Ashaye et al., 2003; Hamid et al., 2009) as well as for the evaluation of mental health care (Hamid et al., 2009).

When considering mental health, a need represents a gap between what is and what should be (Witkin & Altschuld, 1995), and any changes that are made to the system should thus work to reduce this gap. There are various definitions of both “need” and “assessment” (Royse & Drude, 1982). Kahn (1969) considered needs from a social perspective to represent what someone requires in a broader bio-psycho-social context to be able to fully and productively participate in a social process (Royse & Drude, 1982). Brewin conceptualised needs (Lesage, 2017) as assessing what kind of social disability an individual has for professionals to be able to use an adequate model of care. Disability in this context is the result of interactions between people and the environment, and thus a disability can be seen as a lack of appropriate care models in relation to recognized needs. The concept of “need” in mental health care may be defined according to different points of view: a “normative need” is defined by professionals, while a “felt need” is what people with mental health problems experience and ask to be met (Endacott, 1997). What patients request and what they really need may differ, as they can only get what is available and provided at the system level, and what is the most beneficial for them in the current situation. Moreover, what they ask for is not always feasible. However, according to Bradshaw, what an individual requests is important and should be considered as felt needs (Endacott, 1997). Bearing in mind Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, only a combination of assessments from different points of view can provide a comprehensive needs assessment: needs assessed at the individual level from service users, their family members, caregivers, practitioners, and other professionals (Endacott, 1997). Indicators of needs at the individual level include functioning on different levels, symptoms, diagnoses, quality of life and, access to services (Aoun et al., 2004). Patient-centredness is vital to ensure the highest quality of care through monitoring performance (Kilbourne et al., 2018). Taking into account the patients’ perspective is also important to assess needs correctly, since such an assessment is more than just the professionals’ perception. An assessment of needs, as Thornicroft (1991) pointed out, provides care in the community with an emphasis on the provider-user relationship as a key component through which effective care is organized (Carter et al., 1995). According to Slade (1994), the concept of a need in mental health has no single correct definition, but it should rather be seen s a “socially-negotiated concept” (Thornicroft & Slade, 2002). Additionally, needs have to be assessed through the bio-psycho-social model (Makivić & Klemenc-Ketiš, 2022), including not just medical needs but also a wide array of social needs.

Initially, the assessment of needs (Balacki, 1988) in the community was seen as an approach using different forms of analysis to gain insights into the use of services, characteristics of people, incidence and prevalence rates and indicators to recognize crucial determinants that lead to the worsening of mental health. The assessment of mental health needs in Western societies began in 1775 with the analysis of public health data contained in the case registers (Royse & Drude, 1982). In the mid-1970s, with the beginning of the transition to care for mental health in the community (and the launch of community mental health service organizations), needs assessment was required within the evaluation process to help meet the patients’ needs. Needs assessment also represents a crucial part of mental health planning (Royse & Drude, 1982), where different needs must be considered, especially those felt by individuals. At the end of seventies, Kimmel pointed out that this area of needs assessment had no systematic procedures (Royse & Drude, 1982). However, several mental health needs assessment tools have been developed over the last thirty years.

The MRC Needs for Care Assessment (NFCAS) (by Brewin, 1987) was the first attempt to introduce a standardized assessment of the needs of the severely mentally ill (Lesage, 2017). Subsequently, a reduced version of the instrument applicable to common mental disorders was developed – i.e., the Needs for Care Assessment Schedule-Community version (NFCAS-C) (Bebbington et al., 1996). The shortened version of NFCAS was the Cardinal Needs Schedule (CNS), which is used to assess needs to address them with appropriate interventions (Marshall et al., 1995). Later the self-administered Perceived Needs for Care Questionnaire (PNCQ) was developed for use at the population level (Meadows et al., 2000), while in 1995 the Camberwell Assessment of Need (CAN) (Phelan et al., 1995) was published. After this time the focus shifted more to people-centred approaches, and therefore the assessment of needs also moved beyond psychiatric symptomatology to bring in “consumers”, i.e. patients and their caregivers. Other scales have also been used as needs assessment tools, such as the HoNOS scale (Joska & Flisher, 2005) which was designed to evaluate the clinical and social outcomes of mental health care.

Needs assessment is not always a clear and straightforward process with one approach and one goal. Therefore, different tools and approaches may be used to assess needs from different perspectives at different levels and with the help of different tools. The problem with using different techniques is that there is a lack of comparability and a consequent danger of not using the needs assessment outcome data as intended (Stewart, 1979); thus, it is important to have a good overview of the available tools.

To the best of our knowledge, only six reviews on needs assessment in people with mental health problems have been published to date (Davies et al., 2018, 2019; Dobrzyńska et al., 2008b; Joska & Flisher, 2005; Keulen-de Vos & Schepers, 2016; Lasalvia et al., 2000b). Four additional reviews focused on the general needs or general health needs of people without mental health problems (Asadi-Lari & Gray, 2005; Carvacho et al., 2021; Lasalvia et al., 2000a; Ravaghi et al., 2023), which was not focus group of our review. Finally, another article was considered inadequate for this study’s purposes, as it was published in Polish (as the one above) and is not a review paper (Dobrzyńska et al., 2008a). None of the reviews published thus far have focused on the different assessment tools available for assessing the needs of people with different mental disorders. To date, no study has attempted to review all the available published studies on the various needs assessment processes to systematize the topic. The reviews mentioned above deal with only one specific population (patients with first-episode psychosis; forensic patients), or with specific needs (need for mental health services, supportive care needs, or individual needs for care). Thus, this study aimed to review all studies addressing needs assessment tools specifically designed for people with mental health problems, regardless of their diagnoses. The added value of this study is especially because of its wholeness in presenting different tools that can be used on different populations and by different groups. Thus this study may serve as a framework for starting different needs-assessment processes.

Methods

Search strategy

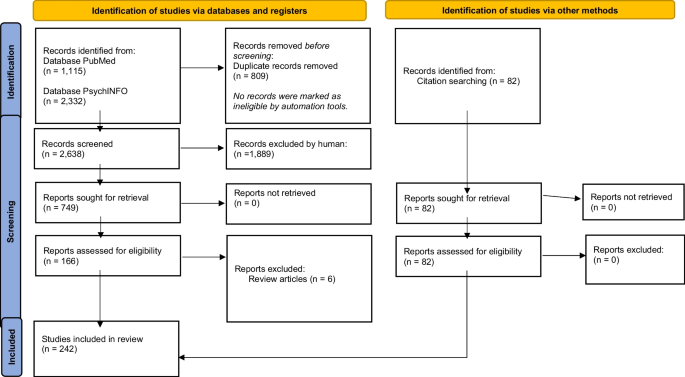

A comprehensive literature search using the Boolean operators “Mental health” AND “Needs assessment” was conducted in electronic bibliographic databases PubMed [Needs Assessment (Mesh Terms) AND Mental Health (Mesh Terms); Mental Health (Title/Abstract) AND Needs assessment (Title/Abstract);] and PsychINFO [Needs assessment AND Mental health in keywords; Needs assessment AND Mental health in Title; Needs assessment AND Mental health in Abstract]. Searching was carried out with the inclusion of all results without time or other limits in August 2021. The search strategy was based on the needs from a clinical context as well as some research priorities in the field of mental health. After the first systematic search we collected additional papers with an overview of six review articles (Davies et al., 2018, 2019; Dobrzyńska et al., 2008b; Joska & Flisher, 2005; Keulen-de Vos & Schepers, 2016; Lasalvia et al., 2000b) and their results, and by searching PubMed within all connected articles. This was important since keywords changed over all this broad timeframe.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Our research exclusively focused on quantitative studies. We thus excluded all theoretical/conceptual articles, editorials, books, book commentaries or dissertations. Studies assessing the needs of patients with dementia and groups of people with physical and psychological disabilities were also excluded. We did not include papers related to 1) only general health (care), 2) other needs of the general population, 3) screening, prevalence, general diagnostic tools, and 4) tools for assessing caregivers’ needs. All those steps were done comprehensively by two researchers (IM, AK) independently. When there was a disagreement on the inclusion or exclusion of an article, both researchers looked at it again before reaching a consensus. We then manually added all relevant articles that could have been missed during the electronic search. We added articles that were cited within or were related with all the six mentioned reviews, but were not yet retrieved in the first search. These review articles were not included in the final number of all the articles examined in this study with the aim of exploring the different tools used for needs assessment of people with mental health problems. The aim of this process is to first obtain an overview of all the tools available, as this will make it possible to better use them within clinical settings, as well as for research and development purposes in order to plan a system or intervention that addresses the recognized needs (Fig. 1).

Scoping studies, as Arksey and O'Malley (2005) mentioned, follow five steps, which we also took into consideration. First (step one) we identified the research question, which was “What are all different needs assessment tools that have been used in the population of people with mental health problems within different studies”. We then identified the relevant studies within recognised databases, as well as manually searching and adding the relevant articles (step two). We selected the appropriate studies (step three) as described within the search strategy process, with all inclusion and exclusion criteria. Finally, we presented the results (step four) in the chart flow in Fig. 2, and Tables 1, 2 and 3, which corresponds to the concept of patient-centred care based on needs (Fig. 1). Because our focus was on different tools, we prepared the tables accordingly. There was no other relevant information in the original 242 articles to be presented at this occasion, other than those about the usage of different needs assessment tools, as this was the goal of the scoping review. The presentation of the results is based on the use of all recognized needs assessment tools, since geographical studies have been presented elsewhere (Makivić & Kragelj, 2023).

Results

The analysis was multi-structured to provide an overview of all the recognized tools and the related time trends, country use and population of the most frequently used assessment methods.

The study selection process is shown in Fig. 2. PubMed provided 578 records within the Mesh search and 537 within the title/abstract search, with after duplicates were removed this gave 1,090 results. Searching in PsychINFO provided 650 results from a search within the Abstract, 232 within Keywords and 1450 within Title; after combining these and removing duplicates, a total of 1,548 results were obtained.

The first selection was made within the final database (n = 2,638) by reading the abstracts and excluding all studies covering topics not relevant for this review. After this was completed, 166 articles remained. These were reviews and research articles covering the needs assessment of people with mental disorders (MD). After this, we eliminated review articles (n = 6) and used them for additional search to manually add all relevant articles that could have been missed during the electronic search, mainly because of the use of different keywords. Specifically, we added the articles that were cited within or were related to all the six mentioned reviews, but were not found in the first search (n = 82). After this process, a total of 242 articles were included in the final review.

Most studies addressing needs assessment tools retrieved with both electronic and manual searches were published in English (n = 231), although some were published in German (n = 3), Spanish (n = 3), and Italian (n = 2). Only one article each was published in Dutch, French and Turkish. Regarding the geographical distribution, most studies were published from European groups (n = 163), while 43 studies were conducted in America, 22 in Australia or New Zealand, 11 in Asia and only three in Africa. Some of the studies were published in collaboration among researchers from different countries. Regarding the publication period, the first studies on this issue were published in 1978, 52.9% of the studies were published from 2000 to 2012, and 66.1% had been published further by 2016.

Through the search performed in this study we found 29 different needs assessment tools, as shown in Table 1 in alphabetical order. We have made and additional search in order to find original sources and the information about the validation. Original sources for each of the recognized tools are listed in Supplementary information (SI 1). Some tools, additional to those 29, were developed for the purposes of a single research study and its specific aims and the information about the validation were not available (n = 11), and thus we eliminated those tools at this point, although they will later be presented elsewhere in another study.

The retrieved tools and their respective constructs of need are presented in Table 2. The various needs assessment tools are listed in alphabetical order. The tools are presented with regard to (1) who can answer the scale, (2) who the target population is, and (3) the domains addressed. Table 2 provides information on the various needs assessment tools, listed in alphabetical order. The tools are presented with regard to (1) who can answer the scale, (2) who the target population is, and (3) the domains addressed.

Service needs (Hamid et al., 2009) are defined as care requirements for prevention, treatment and rehabilitation. These needs can either be assessed by waiting lists or by only asking a simple question (e.g. “Do you think that you require any professional mental health services?”) along with the screening for mental and physical health problems (Yu et al., 2019) or social problems, with the help of the tools listed below. Moreover, there are different bio-psycho-social needs that are related to various mental health, physical health, and quality of life factors, as well as personal interests or abilities and social factors (Keulen-de Vos & Schepers, 2016), and these can be measured for different purposes. Social needs can be assessed by tools such as the Social Behavioral Schedule or REHAB Schedules, and therefore the need for rehabilitation can also be assessed (Hamid et al., 2009) using the comprehensive tools mentioned in our review.

Most of the needs assessment tools were self-completed by the patients (n = 85), completed by professionals (n = 41), or by combination of both (n = 78). Some tools were also completed by the patients and their caregivers (n = 12) or by the patients, caregivers, and professionals at the same time (n = 12). There were few studies where the researchers completed the needs assessment tool (n = 5). The majority of the tools were developed for assessing needs in an adult population with mental health problems (n = 193), either with severe mental disorders or with some other mental health diagnosis. Seventeen studies focused on an elderly population with mental health problems, and six on children with mental health problems. Some needs assessment tools for specific populations were found, such as tools for assessing the needs of forensic patients with mental health problems (n = 18), homeless people and migrants with a mental health diagnosis (n = 4), and mothers or pregnant women with a severe mental disorder (n = 1). In some studies, there was a combination of all these different populations and even people without a diagnosis, which we assigned to each of the mentioned groups.

In the second Supplementary information (SI 2) there are reported the studies found in the literature search that used recognized needs assessment tools (n = 227). In this presentation some of the studies are not presented, namely those without validated tools (n = 11) as already mentioned and all articles using mentioned three different models (n = 4). In some studies, more tools have been used and in this case the study is counted within each tool in the total number of studies. Among the different needs-assessment tool, the CAN is mentioned as the most frequently used scale and, to the best of our knowledge, it has the highest number of different versions. The tools are presented based on their frequency of recognized use within this scoping review, from the most frequent to the least.

The recognized tools can be used in different contexts. Table 3, groups the needs assessment tools according to their use at the care, research, and system levels.

Discussion

This scoping review addressed all the published needs assessment tools specifically designed for use in mental health field. Nevertheless, some of the reviewed tools had also been used on the populations without a mental health diagnosis (Carvacho et al., 2021). Overall, we found twenty-nine different tools measuring needs in various mental health populations. The list of authors of the originally developed scales mentioned below are provided in the Supplementary information (SI 1).

The reviewed literature highlights that the majority of needs assessment tools have been developed and used in Europe as the adoption of a community psychiatry model is relatively more widespread in this region than in other world regions; some tools, however, have been also used in America, Australia, and New Zealand.

Some scales had been developed with the aim to simplify or shorten previously published needs assessment tools, such as the Camberwell Assessment of Need (CAN) derived from the MRC Needs for Care Assessment Schedule. Similarly, the Difficulties and Needs Self-Assessment Tool was derived from the CAN, where some items are identical, some are a combination of several items of the CAN and some were added as new ones (on work, public places, family and friendship). Some tools, like the Montreal Assessment of Needs Questionnaire, were also developed from the CAN and had different aims, like enhancing data variability to broaden outcome measures for service planning, or simply because the organization of the related system is different and other tools are more appropriate. On the other hand, some tools are based on the CAN, but have been designed for use on a larger scale at the population level, like the Needs Assessment Scale. While most of the tools are used within health care services, the Resident Assessment Instrument Mental Health is a tool developed to support a seamless approach to person-centred health and social care. Some of the tools can also be used outside of the mental health field – such as the Child and Adolescent Needs and Strengths, which can be used in juvenile justice, intervention applications and child welfare – and the abovementioned CAN and others.

There are slightly different ideas regarding the needs and concepts about measuring needs. Many tools include a combination of needs assessed from different perspectives, such as the Bangor Assessment of Need Profile and the CAN. In some tools, like the Community Placement Questionnaire, it is predicted that various people rate the situation for one patient to eliminate any inaccuracies. On the other hand, some tools presented here, like the Self-Sufficiency Matrix, measure needs indirectly through self-sufficiency. When there is higher self-sufficiency for a certain life domain then there is less need presented for this area. Some tools, like Services Needed, Available, Planned, Offered, are complicated to use, since they include an investigation method with the review of the tool and assessment of the service use after the needs have been recognized. But this can be a good approach for the evaluation of the performance of community mental health centres about meeting the needs of their patients. Although we must bear in mind that such a tool is not directly transferable to every community mental health centre, as this depends on how each system is organized.

Needs can be evaluated according to different points of view, from patients themselves and their caregivers, as well as professionals. Studies show there are different outcomes based on the assessor (Lasalvia et al., 2000a, b, c; Macpherson et al., 2003), and that professionals may see the needs differently to the users. Therefore, it is important not only what the tool is being used, but also who can complete it. Therefore, the most useful tools are the ones that can be used by various different people, so that the needs are assessed (also) from the patients’ standpoints (Larson et al., 2001).

Although the CAN is the most widely used tool, the research shows that sometimes there is not a very high agreement between staff and patients about needs, as was also found with the Health of the Nation Outcome Scales (HoNOS), which is the reason why some additional scales, such as the Profile of Community Psychiatry Clients, were developed. There are also some tools, such as the HoNOS, that indirectly measure needs for care, so they can be used as either a clinical or needs assessment tool.

Needs assessment tools are generally used by community psychiatry organizations and are also used to support changes to the organizations of countries’ related systems. The tools have already been used in order to assess the needs within clinical procedures, as well as at higher organizational levels in order to supplement services and direct programming (Royse & Drude, 1982). Different tools have good potential to evaluate community mental health services through assessing if patients’ needs have been met. Therefore, this study also aims at answering the question of which tool(s) can be most appropriate regarding different goals.

Within this review, we identified three systematic approaches to needs assessment which encompass different tools. The first is the DISC (Developing Individual Services in the Community) Framework (Smith, 1998), which includes the CAN and the Avon Self-Assessment Measure. The second is the Cumulative Needs for Care Monitor (Drukker et al., 2010), developed in order to choose the best treatment for each person. This one also uses the CAN and other more clinical tools and outcome measures (such as quality of life). The third is the Colorado Client Assessment Record (Ellis et al., 1984), which includes different measures of social functioning, such as the Denver Community of Mental Health Questionnaire, the Community Adjustment Profile, the Fort Logan Evaluation Screen, the Personal Role Skills Scale and the Global Assessment Scale.

This study has several strengths. First, we searched for as many tools and articles as possible. Second, we followed the standard rules of systematic and scoping reviews to present the data in a structured and non-biased manner: we thus searched for information extensively; the search was transparent and reproducible; the data were presented in a structured way. Finally, the scoping review was carried out, since the goal was not to compare and assess the quality of the evidence in the studies, but rather to review of all potential tools that can be used within the process of assessing the needs. Third, this study considered different populations, from severe mental disorders to other mental health problems, including addiction, which produced a strong overview of different tools and versions of the same tool used in other contexts. Fourth, the use of such tools also has a different basis depending on the goals of the system, so it can reflect the organization of care for mental health in a given country. The fifth strength of this work is that in addition to the original 242 articles within the review, we have also included all original sources for development of each of the 29 recognized tools.

This study also has some limitations. First, as the keywords are not same for every study, some studies could have been left out and therefore some tools might have been unrecognized. Second, our needs assessment review focuses on all people with mental health problems, even though the group of those with severe mental illness differs from the group with less severe mental health disorders. Therefore, no conclusion can be made on which tool is better for use in different population groups or disease severities. Third, we only included tools that assess the needs of people with mental health problems, although other tools for the general population could also potentially be useful. Fourth, some tools were developed and validated in only one country, so transferability is questionable or requires additional validation.

Since this scoping review provides insight into the evidence about the existence of different tools for needs assessment, it would also be valuable to conduct additional research on the level of each tool to see if it has already been validated and culturally adapted. To the best of our knowledge, the CAN is the most frequently used tool, and has been translated and adapted into more than 33 different languages (Phelan et al., 1995). Some of the tools reviewed in this study use items similar to the CAN, such as the Needs Assessment Scale (de Weert-van Oene et al., 2009). Some tools use the same items with a few additional ones, such as the Montreal Assessment of Needs Questionnaire (Tremblay et al., 2014), which shows even greater use of the CAN. Thus, the concepts in this latter tool are widely applied.

Conclusion

There are different fields in which certain needs must be addressed to deal with the mental health of the general population or the needs of the population with mental health problems, with the latter being our main focus. This review aimed to develop a tool for needs assessment that can be applied clinically and for research purposes. It is also vital to see what kind of tools can be used to assess needs for the purpose of a formative evaluation process, and the possibility of service development following the identification of actual needs (Makivić et al., 2021). Therefore, this article is valuable for a variety of final users, as it can be used by service providers at the level of health or social care, researchers, policymakers and other relevant stakeholders.

Moreover, it is also necessary to assess needs in the field of communication, especially targeting anti-stigma and anti-discrimination campaigns, and to assess the needs of educational systems (Kragelj et al., 2022) for the representation of mental health topics (Makivić et al., 2022). The use of different tools for assessing needs not only gives us the possibility of identifying such needs, but also establishes the possibility of meeting those needs when these tools are used within bio-psycho-socially oriented primary care or interdisciplinary-oriented mental health care. The assessment of needs at the individual level is important for the effective development of person-centred care plans (Martin et al., 2009). Patient-centred psychiatric practice is also needed to increase patient empowerment, which can be done with the help of a needs assessment process.

The review of all the tools for assessing different needs for people with mental health problems presented in this work is new, and therefore fills an important gap in the scientific knowledge of the needs assessment process in the field of mental health.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Aoun, S., Pennebaker, D., & Wood, C. (2004). Assessing population need for mental health care: A review of approaches and predictors. Mental Health Services Research, 6(1), 33–46. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:mhsr.0000011255.10887.59

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

Asadi-Lari, M., & Gray, D. (2005). Health needs assessment tools: Progress and potential. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, 21(3), 288–297. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0266462305050385

Ashaye, O. A., Livingston, G., & Orrell, M. W. (2003). Does standardized needs assessment improve the outcome of psychiatric day hospital care for older people? A randomized controlled trial. Aging & Mental Health, 7(3), 195–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360786031000101166

Balacki, M. F. (1988). Assessing mental health needs in the rural community: A critique of assessment approaches. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 9(3), 299–315. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612848809140931

Bebbington, P., Brewin, C. R., Marsden, L., & Lesage, A. (1996). Measuring the need for psychiatric treatment in the general population: the community version of the MRC Needs for Care Assessment. Psychological Medicine, 26(2), 229–236. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291700034620

Carter, M. F., Crosby, C., Geerthuis, S., & Startup, M. (1995). A client-centered assessment of need needs assessment. Journal of Mental Health, 4(4), 383–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638239550037433

Carvacho, R., Carrasco, M., Lorca, M. B. F., & Miranda-Castillo, C. (2021). Met and unmet needs of dependent older people according to the Camberwell Assessment of Need for the Elderly (CANE): A scoping review. Revista Espanola De Geriatria y Gerontologia, 56(4), 225–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regg.2021.02.004

Davies, E. L., Gordon, A. L., Pelentsov, L. J., Hooper, K. J., & Esterman, A. J. (2018). Needs of individuals recovering from a first episode of mental illness: A scoping review. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 27(5), 1326–1343. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12518

Davies, E. L., Gordon, A. L., Pelentsov, L. J., & Esterman, A. J. (2019). The supportive care needs of individuals recovering from first episode psychosis: A scoping review. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 55(1), 6–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12259

de Weert-van Oene, G. H., Havenaar, J. M., & Schrijvers, A. J. (2009). Self-assessment of need for help in patients undergoing psychiatric treatment. Psychiatry Research, 167(3), 221–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2008.02.001

Dobrzyńska, E., Rymaszewska, J., & Kiejna, A. (2008a). CANSAS-Krótka Ocena Potrzeb Camberwell oraz inne narzedzia oceny potrzeb osób z zaburzeniami psychicznymi [CANSAS-Camberwell Assessment of Need Short Appraisal Schedule and other needs of persons with mental disorders assessment tools]. Psychiatria Polska, 42(4), 525–532.

Dobrzyńska, E., Rymaszewska, J., & Kiejna, A. (2008b). Potrzeby osób z zaburzeniami psychicznymi–definicje, przeglad badań [Needs of persons with mental disorders-definitions and literature review]. Psychiatria Polska, 42(4), 515–524.

Drukker, M., Bak, M., Campo, J.à, Driessen, G., Van Os, J., & Delespaul, P. (2010). The cumulative needs for care monitor: a unique monitoring system in the south of the Netherlands. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 45(4), 475–485. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-009-0088-3

Ellis, R. H., Wilson, N. Z., & Foster, F. M. (1984). Statewide treatment outcome assessment in Colorado: The Colorado Client Assessment Record (CCAR). Community Mental Health Journal, 20(1), 72–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00754105

Endacott, R. (1997). Clarifying the concept of need: A comparison of two approaches to concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 25(3), 471–476. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.1997025471.x

Hamid, W. A., Lewis-Cole, K., Holloway, F., & Silverman, M. (2009). Older people with enduring mental illness: A needs assessment tool. Psychiatric Bulletin, 33(3), 91–95. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.bp.107.017392

Joska, J., & Flisher, A. J. (2005). The assessment of need for mental health services. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 40(7), 529–539. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-005-0920-3

Keulen-de Vos, M., & Schepers, K. (2016). Needs assessment in forensic patients: A review of instrument suites. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 15(3), 283–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/14999013.2016.1152614

Kilbourne, A. M., Beck, K., Spaeth-Rublee, B., Ramanuj, P., O’Brien, R. W., Tomoyasu, N., & Pincus, H. A. (2018). Measuring and improving the quality of mental health care: A global perspective. World Psychiatry: Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 17(1), 30–38. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20482

Kragelj, A., Pahor, M., Zaletel-Kragelj, L., & Makivic, I. (2022). Learning needs assessment among professional workers in community mental health centres in Slovenia: Study protocol. South Eastern European Journal of Public Health, Special Volume No. 1. https://doi.org/10.11576/seejph-5478

Larson, A., Frkovic, I., van Kooten-Prasad, M., & Manderson, L. (2001). Mental health needs assessment in Australia’s Culturally Diverse Society. Transcultural Psychiatry, 38(3), 333–347. https://doi.org/10.1177/136346150103800304

Lasalvia, A., Stefani, B., & Ruggeri, M. (2000a). I bisogni di cura nei pazienti psichiatrici: una revisione sistematica della letteratura. I. Concetti generali e strumenti di valutazione. I bisogni di servizi [Therapeutic needs in psychiatric patients: a systematic review of the literature. I. General concepts and assessment measures. Needs for services]. Epidemiologia e Psichiatria Sociale, 9(3), 190–213. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1121189x00007879

Lasalvia, A., Stefani, B., & Ruggeri, M. (2000b). I bisogni di cura nei pazienti psichiatrici: una revisione sistematica della letteratura. II. I bisogni di cura individuali [Needs for care in psychiatric patients: a systematic review. II. Needs for care on individual]. Epidemiologia e Psichiatria Sociale, 9(4), 282–307. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1121189x00008411

Lasalvia, A., Ruggeri, M., Mazzi, M. A., & Dall'Agnola, R. B. (2000). The perception of needs for care in staff and patients in community-based mental health services. The South-Verona Outcome Project 3. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 102(5), 366–375. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.102005366.x

Le Grand, D., Kessler, E., & Reeves, B. (1996). The avon mental health measure. Mental Health Review Journal, 1(4), 31–32. https://doi.org/10.1108/13619322199600042

Lesage, A. (2017). Populational and individual perspective on needs. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 26(6), 609–611. https://doi.org/10.1017/S204579601700049X

Macpherson, R., Varah, M., Summerfield, L., Foy, C., & Slade, M. (2003). Staff and patient assessments of need in an epidemiologically representative sample of patients with psychosis-staff and patient assessments of need. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 38(11), 662–667. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-003-0669-5

Makivić, I., & Klemenc-Ketiš, Z. (2022). Development and validation of the scale for measuring biopsychosocial approach of family physicians to their patients. Family Medicine and Community Health, 10(2), e001407. https://doi.org/10.1136/fmch-2021-001407

Makivić, I., & Kragelj, A. (2023). Needs assessment tools at the field of mental health: Countries presentation. V: Conference abstract book: 11th European Conference on Mental Health [S. l.]: Evipro, Str. Ljubljana, Slovenia, p. 184.

Makivić, I., Švab, V., & Selak, Š. (2021). Mental health needs assessment during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Consensus based on Delphi Study. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 732539. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.732539

Makivić, I., Kragelj, A., & Selak, Š. (2022). Educational needs assessment in the field of mental health: Review of the tools. V: 10th European conference on mental health: Conference abstract book. Evipro, Str. Lisbon, Portugal, Helsinki, pp. 183–184.

Marshall, M., Hogg, L. I., Gath, D. H., & Lockwood, A. (1995). The cardinal needs schedule-a modified version of the MRC needs for care assessment schedule. Psychological Medicine, 25(3), 605–617. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291700033511

Martin, L., Hirdes, J. P., Morris, J. N., Montague, P., Rabinowitz, T., & Fries, B. E. (2009). Validating the Mental Health Assessment Protocols (MHAPs) in the Resident Assessment Instrument Mental Health (RAI-MH). Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 16(7), 646–653. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2009.01429.x

McGorry, P. D., & Hamilton, M. P. (2016). Stepwise expansion of evidence-based care is needed for mental health reform. The Medical Journal of Australia, 204(9), 351–353. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja16.00120

Meadows, G., Harvey, C., Fossey, E., & Burgess, P. (2000). Assessing perceived need for mental health care in a community survey: Development of the Perceived Need for Care Questionnaire (PNCQ). Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 35(9), 427–435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001270050260

Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

Phelan, M., Slade, M., Thornicroft, G., Dunn, G., Holloway, F., Wykes, T., Strathdee, G., Loftus, L., McCrone, P., & Hayward, P. (1995). The Camberwell assessment of need: The validity and reliability of an instrument to assess the needs of people with severe mental illness. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 167(5), 589–595. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.167.5.589

Ravaghi, H., Guisset, A. L., Elfeky, S., Nasir, N., Khani, S., Ahmadnezhad, E., & Abdi, Z. (2023). A scoping review of community health needs and assets assessment: Concepts, rationale, tools and uses. BMC Health Services Research, 23(1), 44. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08983-3

Royse, D., & Drude, K. (1982). Mental health needs assessment: Beware of false promises. Community Mental Health Journal, 18(2), 97–106. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00754454

Slade M. (1994). Needs assessment. Involvement of staff and users will help to meet needs. The British journal of psychiatry: the journal of mental science, 165(3), 293–296. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.165.3.293

Smith, H. (1998). Needs assessment in mental health services: The DISC framework. Journal of Public Health Medicine, 20(2), 154–160. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.pubmed.a024736

Stewart, R. (1979). The nature of needs assessment in community mental health. Community Mental Health Journal, 15, 287–295. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00778708

Thornicroft, G. (1991). The concept of case management for long-term mental illness. International Review of Psychiatry, 3(1), 125–132. https://doi.org/10.3109/0954026910906752

Thornicroft, G., & Slade, M. (2002). Comparing needs assessed by staff and by service users: Paternalism or partnership in mental health? Epidemiologia e Psichiatria Sociale, 11(3), 186–191. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1121189x00005704

Tremblay, J., Bamvita, J. M., Grenier, G., & Fleury, M. J. (2014). Utility of the Montreal assessment of need questionnaire for community mental health planning. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 202(9), 677–687. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000180

Witkin, B. R., & Altschuld, J. W. (1995). Planning and Conducting Needs Assessments: A Practical Guide. Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.1177/002087289603900316

Wykes, T., Bell, A., Carr, S., Coldham, T., Gilbody, S., Hotopf, M., Johnson, S., Kabir, T., Pinfold, V., Sweeney, A., Jones, P. B., & Creswell, C. (2021). Shared goals for mental health research: what, why and when for the 2020s. Journal of Mental Health (Abingdon, England), 1–9. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2021.1898552

Yu, J. Y., Dong, Z. Q., Liu, Y., Liu, Z. H., Chen, L., Wang, J., Huang, M. J., Mo, L. L., Luo, S. X., Wang, Y., Guo, W. J., He, N., Chen, R., & Zhang, L. (2019). Patient-doctor concordance of perceived mental health service needs in Chinese hospitalized patients: a cross-sectional study. Annals of Palliative Medicine, 8(4), 442–450. https://doi.org/10.21037/apm.2019.08.06

Funding

This work was supported by the Slovenian Research Agency (project No.: Z3-2652).[Display Image Removed]. Project was funded by the Reseach agency. Only IM was paid from this. But the project didn't finance the outcomes and the goal of publishing this work was solely for the research purposes.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: [Irena Makivić]; Methodology: [Irena Makivić]; Formal analysis and investigation: [Irena Makivić], [Anja Kragelj]; Writing—original draft preparation: [Irena Makivić]; Writing—review and editing: [Irena Makivić], [Anja Kragelj], [Antonio Lasalvia]; Funding acquisition: [Irena Makivić]; Resources: [Irena Makivić]; Supervision: [Antonio Lasalvia].

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

There are no financial or non-financial interests that are directly or indirectly related to the work submitted for publication. All authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

There was no need to apply for ethical committee or for informed consent, since there were no humans directly involved in this scoping review.

Embargoes

Embargoes on data sharing are permitted.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Makivić, I., Kragelj, A. & Lasalvia, A. Quantitative needs assessment tools for people with mental health problems: a systematic scoping review. Curr Psychol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-05817-9

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-05817-9