Abstract

Background

This study explores morphologic changes in the Ahr River, Germany, caused by the high-energy flood in mid-July 2021. This study aims to assess the flood's significance as a morphological driver using the Lateral Mobility Index (LMI), as well as the impact of infrastructure on morphodynamics in terms of the formation of mud deposits and stagnant water pools, considering three focus areas of about 1 to 5 km river length. The three focus areas cover differences in the valley morphology as well as near natural and anthropogenically affected sections.

Results

The LMI is derived from orthophotos from 1998 to 2022, and based on the surface area of the old and the new channel. It describes the sum of new and abandoned channel area in relation to the previous channel area. For the 2021 high-energy event, an increased LMI suggests an increasing change in river course and morphology. Post-flood, the LMI in focus areas 1 (furthest upstream, LMI of 1.5) and 3 (at the Rhine confluence, LMI of 3.2) surpasses the historic LMI by a factor of about 3. Focus area 3 exhibits the highest activity, while focus area 2 (LMI between 0.25 and 0.70) the lowest. The area of mud deposits and stagnant water pools increased immediately after the flood, especially in focus area 3. Over the following months, initial post-flood mud deposits not only washed away but also rebuilt to some degree later on.

Conclusions

The LMI enabled to quantitatively identify a rare and significant morphological disruption in the Ahr River’s lateral development in three focus areas, and thus, serves as additional proof that the flood of mid-July 2021 was a high-energy event impacting the local river geomorphology. Infrastructure impacted the formation of mud deposits and stagnant water zones during and after the flood, with additional influence from factors such as driftwood and valley width. The data suggested a phase of resuspension of sediments after the flood, likely due to cleanup and ad hoc river management, highlighting the need for continued river monitoring.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

High-energy flood events are short-term events and part of the natural evolution of a river. Differences between long-term, slow morphological changes, and rapid large-scale changes in river systems from high-energy events are first explained by Wolman and Miller [1]. They stated that annual to bi-annual flood events shape the general morphology of especially alluvial rivers [1]. However, during high-energy events, even less erodible sediments are mobilized [1], leading to shoal formation and lateral channel shifts [2,3,4,5,6]. The challenge is to determine if fluvial morphologic changes accelerate significant geomorphodynamics on a temporal and spatial scale that may represent a possible issue for anthropogenically developed water bodies [1, 7]. This means, for example, a lasting change in the future development of the riverbed. Examples of problematic developments when suddenly and unexpectedly changed can be lasting colmation, riverbed degradation, floodplain decoupling, or re-activation.

In mid-July 2021, a high-energy flood event occurred in the low mountains of western Germany [8,9,10,11,12]. In the Eifel mountains, rainfall summed up to 150 mm in 72 h [13,14,15], exceeding the long-time average total of July by a factor of up to 2 [13]. It is estimated that the rainfall event has a return period of one in 400 years [16]. In Germany, the Ahr Valley in Rhineland-Palatinate (RLP) was most severely affected [10, 17].

Large sediment displacements occurred along the Ahr River [18,19,20,21,22]. Urban areas experienced extensive destruction and mud pollution, with effects still visible two years later [20, 23,24,25,26,27]. Erosion and sediment accumulation were observed near infrastructure elements, such as retaining walls, roads, and bridges [18]. Site visits showed bridges to be one of the most affected infrastructure systems [20, 23, 27]. Particularly upstream of bridges, significant erosion occurred [18, 28]. However, local embankment stabilization also impacted sediment dynamics due to local control of the discharge direction, mostly leading to enhanced erosion [18]. Large volumes of driftwood and debris flow interacted with local infrastructure elements and caused severe flow alterations [22, 23, 25, 26, 29]. Overall, sediment relocation processes were so severe that they laterally shifted the river course in some locations [18, 25].

High-energy flood events have led to bank erosion and lateral shifts of river courses [7, 30, 31] as well as sediment deposition in rivers [7, 32]. Infrastructure systems, such as bridges and fixed embankments, affect morphologic development during flood events [33]. However, direct causal relationships of certain infrastructure elements with specific processes of erosion and sedimentation have remained questionable [33], as they could not be observed, with the exception of upstream erosion at bridges [18].

Heavy rainfall events and resulting riverine flooding are expected to occur more often with climate change [16, 34]. These events also tend to bring excess mud deposits to the riverbed [32, 34], potentially containing pollutants [35,36,37] and leading to riverbed clogging [38]. Furthermore, excess mud deposition and erosion hotspots can lead to stagnant water pools on floodplains which potentially require the attention of watercourse maintenance. Colmation due to excess mud deposition can endanger spawning habitats and habitats in the soil sediments. Stagnant water pools are problematic for anthropogenic usage of floodplain properties.

Post-flood water resources management typically requires information on the lateral river development to assess the severity of the flood. However, various conditions, including geomorphological, hydrological, biological, and biogeochemical factors, influence water body development [2, 39,40,41,42]. Thus, different river sections need to be assessed to account for different environmental conditions. Additional research on the formation and evolution of mud deposits and stagnant water pools is needed to support water resources management in the future.

The aim of this study is to assess if the extreme flood of mid-July 2021 in the Ahr Valley was a significant morphological driver, and if so, in which way. This is evaluated based on the following two research questions:

-

I.

Does the LMI reveal relevant information about lateral development of river sections on the order of 1 to 5 river kilometers (rkm) in length?

-

II.

How do infrastructure systems impact the formation of mud deposits and stagnant water pools within river sections (with section lengths of 1 to 5 rkm) after a high-energy flood and which other parameters play into account?

Methods

Study area

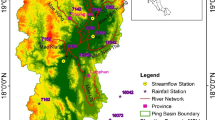

The Ahr River is an 85-km-long river in the Eifel low mountains in western Germany. Its catchment area has a size of 898 km2 (Fig. 1). The Ahr riverbed is predominantly composed of siliceous fine to coarse sediments [43]. The upper reaches in particular are characterized by river gravel. In the middle course, there is shale in the riverbed. Downstream, fine material accumulates between the river gravel. The Ahr River’s eight main tributaries are the Ahbach, Trierbach, and Armuthsbach in the upper catchment, and the Adenauer Bach, Liersbach, Kesselinger Bach, Sahrbach, and Vischelbach in the central catchment. Only smaller tributaries contribute to the lower catchment area. Forests represent 56% of the catchment area, followed by agricultural land use and pastures (36%) [44]. Urban development makes up 6.5% of the catchment area, mostly located in floodplain areas [44].

a Location of the Ahr River’s catchment area in Germany. b Overview of the Ahr River’s catchment and location of the three focus areas. 1: a relatively straight river section in the town of Brück including a historic bridge. 2: mountainous region near the town Altenahr and the “Langfigtal” natural preservation area. 3: confluence to the Rhine River. Data sources: country borders: [45], county border: [46], towns: [47], rivers: [48], flooded area: [49], catchment: [50], buildings: [51], Digital Elevation Model with a resolution of 1 m (DEM1) (NRW): [52], DEM1 (RLP): [53]. Coordinates in ETRS89 / UTM zone 32N

Morphologic changes in the context of the July 2021 flood are evaluated in three focus areas with different natural and anthropogenic constraints (Fig. 1). Focus areas were selected due to observed morphologic differences during field trips in the middle of August 2021, the end of March 2022, and the end of October 2022. Different valley morphologies and anthropogenic impacts are covered, as described in the following.

Focus area 1 is situated the furthest upstream, is a relatively straight section, and represents the shortest section (Table 1). The valley width ranges between 100 and 250 m. The corresponding river width is 10 m to 12 m. Focus area 1 is characterized by a historic bridge in the middle of the sections (50° 29′ 11.7ʺ N, 6° 58′ 17.6ʺ E). Two river bed glides are located in the middle of the focus area. Floodplains are scarcely but continuously populated. The riverbed gradient (4.57 ‰) is steeper than in the other two focus areas, whereas the riverbed gradients in focus area 3 and focus area 2 are similar (3.21 ‰ and 3.34 ‰) (Table 1).

Focus area 2 includes the natural reserve “Langfigtal” (50° 30′ 37.5ʺ N, 6° 59′ 50.0ʺ E), which is a meandering section confined by steep hillslopes. The mean areal slope is 9.8° being the highest of all three focus areas (cf. Table 1). Focus area 2 includes the town of Altenahr, a relatively densely populated urban area with a population of 101 residents per km2 (1492 in total). Altenahr’s main road is routed through a mountain tunnel, which shortcuts the meander bend in the Langfigtal. During the flood in mid-July 2021, a large part of the peak flood waters discharged through this tunnel leading to severe upstream erosion at the tunnel entrance and deep erosion at the downstream exit [18]. The valley width ranges from 270 m in the populated area to 50 m in sections confined by steep valley side slopes resulting from steeply dipping rocks. The river width ranges between 15 and 20 m in this area. In focus area 2, twelve bridges offered river crossings in 2019. In addition, there were 10 grade controls, e.g., shallow weirs.

The closest gauging station to focus areas 1 and 2 is situated in Altenahr (Fig. 1), which was constructed in 1991, and renewed after the flood [55]. Pre-flood values for average discharges are 10.2 m3/s (winter), 3.5 m3/s (summer), and 6.9 m3/s (total) [55].

Focus area 3 extends from a railway and a highway bridge at the beginning of the town of Sinzig (50° 33′ 08.2ʺ N, 7° 15′ 14.8ʺ E) to a pedestrian bridge close to the Rhine confluence of the Ahr River (50° 33′ 32.4ʺ N, 7° 16′ 35.1ʺ E). Bridges appear in all evaluated maps and digital orthophotos (DOPs) ensuring comparability of the river section over time (cf. Table 2). Focus area 3 features mostly low natural riverbanks, besides next to the wastewater treatment plant. River-crossing structures are limited to the bridges mentioned earlier. As it is the confluence area, the valley width of this focus area is large with ~ 1.5 km at its narrowest location before it transitions into lowlands. The corresponding width of the Ahr River is about 20 m. The hillslope is on average 2.8°, being lower than in focus areas 1 and 2 (cf. Table 1).

The closest gauging station to focus area 3 is located near Sinzig, constructed in 1964, and average discharges are 9.0 m3/s (winter), 3.3 m3/s (summer), and 6.2 m3/s (total) [56]. Values are lower than at the gauging station Altenahr, and those discrepancies are known by authorities, but can only be explained by inaccuracies.

Digitalization of river sections and resolution

Table 2 lists the data sources used in this study. Digital orthophotos (DOP) with a resolution of 0.4 m and 0.1 m were evaluated for recent times (1998–2022). Historic hand-sketched maps provided a comparison to the nineteenth century when the area of interest was about ten times less densely populated than today [44].

Within the three focus areas, the objects listed in Table 3 were digitalized based on digital orthophotos and historic maps using QGIS. To determine the Lateral Mobility Index (LMI) [57], the riverbanks within the focus areas were digitalized as a polygon from the two historic maps and the 13 DOPs. Riverbanks from 1803 to 1820 were obtained from “Kartenaufnahme der Rheinlande durch Tranchot und von Müffling” and from 1843 to 1878 obtained from “Preußische Kartenaufnahme, Uraufnahme”. The “Kartenaufnahme der Rheinlande durch Tranchot und von Müffling” was made by the orders of Napoleon for military purposes in scales between 1:10,000 and 1:20,000 [58]. The “Preußische Kartenaufnahme, Uraufnahme” in a scale of 1:25,000 was made after the political reorganization of Europe by the Congress of Vienna (1814 to 1815) to create the first uniform map series for the territory of the Kingdom of Prussia [59]. The historic maps were locally corrected by aligning locations of historic bridges and the location of a castle. Since the rivers were digitalized as polygons, the river surface area can be computed in GIS.

Infrastructure elements (e.g., bridges, bridge piers, and riverbank retaining walls), driftwood, as well as mud deposits and stagnant water pools were mapped with respect to the flood event using the DPOs from 2019, July 2021, September 2021, and June 2022. 2019 imagery served as pre-event baseline. Debris jams on infrastructure elements at the Ahr River, mostly consisting of driftwood [18, 26, 60], were also mapped. Additionally, sand and gravel shoals were digitalized to assess narrowing of the riverbed by those features after the flood event. We summed up the areas of sand and gravel shoals per focus area and divided the sum by the river surface area to obtain the specific area. Lastly, artificial deposits, such as rip-rap (artificial cobble deposits to stabilize the riverbed) in the riverbed were digitalized as polygons based on the DOPs from 2019, July 2021, September 2021, and June 2022 (Table 3). The surface area of the visible artificial deposits and rip-rap in the riverbed were summed up for each year and focus region.

Lateral Mobility Index

The lateral mobility of riverbanks was quantified by Richard et al. [57] introducing the Lateral Mobility Index (LMI). The LMI is usually plotted over the timespan of two evaluated time slices, but it is unable to provide information on the development in between those snapshots. Although it was developed to determine river course changes after damming [57, 61], the LMI has proven to be a promising indicator for river course development in general [61, 62]. The Lateral Mobility Index (LMI), after Richard et al. [57], assesses the lateral mobility of the river channel between two-time slices and is expressed as shown in EQ-1. Based on the surface area of the old and the new channel, the abandoned and new river area is determined (Fig. 2). Figure 2A shows the old and the new channel areas. In the shown example, the new channel area is larger than the old one. Only small areas of the old channel are not covered by the new channel area. Thus, the abandoned channel area (Fig. 2C) is smaller than the new channel area (Fig. 2B):

GIS-based procedure to determine the Lateral Mobility Index (LMI) after Richard et al. [57]. A Old and new river outline at two different times. B New channel area of the new river path in comparison to the old river, C abandoned channel area of the old river in comparison to the new river. The example shows focus area 3 in June 2019 and July 2021

The smallest possible LMI is 0, indicating no changes. Channel narrowing or moderate channel widening leads to values between > 0 and 1. A significant dislocation is indicated by values > 1.

Overlap analysis

The aim of the overlap analysis is to see how many areas of mud deposits and areas of stagnant water pools are possibly resulting from the presence of bridges and bridge piers, other man-made structures, or driftwood deposits. We define a radius around the object as its impact zone, since, for example, a mud deposit caused by flow alterations by a bridge pier does not necessarily touch the pier. If mud deposits or areas of stagnant water pools are located within an impact zone, a relationship between structure and mud deposit or ponding water is assumed and discussed (Fig. 3). Impact zones were defined at bridges and bridge piers, other man-made structures, like riverbank retaining walls, and trees as a radius of 5 m, which is ½ of the minimum river width within all three focus areas. This way impact zones of objects on one riverside do not overlap with others located on the other river side. Then, areas of mud deposits and areas of stagnant water pools that spatially overlap with the impact zones were mapped. If a mud deposits or stagnant water pools falls within the impact zones of a bridge and of driftwood, both impact zones are assigned to it (Fig. 3). Finally, these sub-selected data are summed up according to its overlap with different impact zones. It is estimated which fraction of the total area of mud deposits and stagnant water pools overlaps with the different impact zones.

Example of the overlap analysis located in focus area 2. The mapped mud deposit from July 2021 overlaps with a bridge impact zone and the tree impact zone. Both impact zones are assigned to the mud deposit. DOP: [63]

It was tested whether the list of extracted areas of mud deposits and areas of stagnant water pools (sub-selection) is statistically independent from the statistical population, namely, all areas of mud deposits and areas of stagnant water pools. If the sub-selection and the statistical population are similarly distributed, then the impact zones are unlikely to have affected the distribution of mud deposits and areas of stagnant water pools in the three focus areas. We use the Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test, as datasets are not independent [64], to test if they are statistically independent distributed.

In every focus area, we further added up the areas of mud deposits and areas of stagnant water pools for every evaluated DOP. The sums were divided by the river length in the corresponding focus area (Table 1) to standardize them (specific area). This enables comparison of mud deposits and areas of stagnant water pools within and between the three focus areas despite different river section lengths.

Results

Fig. 4 shows the LMI based on DOPs from May 1998 to June 2022. The lateral mobility was evaluated within timesteps of three years between 1999 and 2007 and two years from 2007 to the flood of mid-July 2021. As the hand-sketched historic maps were created over several decades, the historic LMI covers at least 23 but not more than 75 years (Table 2). Overall, the lateral mobility is the highest in focus area 3, and the lowest in focus area 2 (Fig. 4). For all focus areas, the LMI between 1999 and 2019 was lower (LMI < 0.5) than the historic LMI (0.65 in focus area 1, 1.17 in focus area 2, 1.22 in focus area 3). In focus areas 1 and 3, the LMI between June 27, 2019 and July 24, 2021 exceeded the historic LMI by about a factor of 3. In focus area 2, the LMI only increased slightly during that time. However, in all three focus areas, the discharge peaked during (Fig. 4 blue triangles), and the surface area of the channel after the flood event. After the flood, LMIs in all three focus areas dropped below 0.5 again.

Lateral Mobility Index (LMI) shown as red line of the three focus regions from 1998 to 2022 based on digital orthophotos (DOP) in comparison with the LMI determined from historic maps from 1803 to 1878 (orange dashed line). The area of the river surface in relation to the river surface determined from the first DOP (June 13th 1999) is shown as black crosses. The peak discharge between two-time slices is shown as blue triangles and represents daily averages [65]

Fig. 5 displays the fraction of the riverbed occupied by shoals based on DOPs from May 2019, July 2021, September 2021, and June 2022. In focus area 1, 6% of the channel was occupied by shoals in 2019 and July 2021. After no shoals were apparent in September 2021, 16% of the channel surface was occupied by shoals in June 2022. Focus area 2 was almost free of shoals before the flood. A week after the flood in mid-July 2021, 44% of the channel area was occupied by shoals (Fig. 5). In September 2021, shoal areas decreased to 19% and increased to 29% again in June 2022. In focus area 3, before the flood event of mid-July 2019, 21% of the river outline was occupied by shoals. About a week after the flood, the share of shoals decreased to 15%, but it increased to 61% in June 2022.

Artificial deposits and rip-rap appear first in September 2021 in our imagery (Table 4). In focus area 1, the area of artificial deposits and rip-rap was the largest with 2260 m2. However, only around 200 m2 were identified as artificial deposits or rip-rap in focus area 1 in June 2022. In September 2021 and June 2022, the areas of artificial deposits and rip-rap in focus area 3 were both around 1200 m2. The areas of artificial deposits and rip-rap in focus area 2 increased from around 1120 to 2260 m2.

The Wilcoxon signed rank test [64] was applied to test if the sub-selections of areas of stagnant water pools and mud deposits with an overlap with the different impact zones were dependent on the parent population. The datasets were found independent with p-values of 0.0002 to 0.0004. This means that the sub-selections behaved differently from the distribution of mud deposits and stagnant water pools over the three focus areas.

The specific areas of mud deposits and stagnant water pools in the three focus areas were assessed from the DOPs of May 2019, July 2021, September 2021, and June 2022, and are shown in Fig. 6. Most mud deposits and stagnant water pools were observed in focus area 3 in the DOP of July 24, 2021, being about a week after the high-energy flood. The specific area of mud deposits over time followed a similar pattern in all three focus areas. In 2019, mud deposits were only visible in focus area 3 and partly fell within the bridge impact zones. After the peak in July 2021, visible mud deposits decreased in September 2021 and slightly increased again in June 2022. In July 2021, the largest overlap of mud deposits with the impact zones of uprooted trees and driftwood was observed (70% in focus area 3, 96% in focus area 2, 67% in focus area 1). In focus areas 1 and 2, more than a third of mud deposits additionally fell within the impact zones of man-made structures, namely, artificial embankments to protect streets and settlements. In September 2021, the overlap of mud deposits with impact zones was the smallest. In focus area 2, 11% of the mud deposits overlapped with the impact zone of trees and 14% with artificial structures other than bridges (e.g., riverbank retaining walls). In focus area 2, the impact zones of bridges and other artificial structures overlapped with 12% of the areas of mud deposits. In June 2022, the overlap of mud deposits with impact zones ranged between 30 and 73%. This time, the overlap was with bridges and other artificial structures in focus area 2, other artificial structures in focus area 1, and with trees in focus area 3.

Specific area of mud deposits and stagnant water pools in the three focus areas and their overlap analysis with bridges, bridge piers, other artificial structures, and driftwood. Graphs show the specific area of mud deposits and stagnant water pools in m2 per rkm (river length in the focus area) based on evaluated DOPs (2019, Jul. 2021, Sept. 2021, Jun. 2022). Pie charts show the overlap of mud deposits and stagnant water pools with the impact zone of bridges and bridge piers, other artificial structures, such as riverbank retaining walls, and trees

In focus area 3, large areas of stagnant water pools (SWP) occurred after the flood and mostly overlapped with the impact zone of uprooted trees (Fig. 6). SWP overlapped only 1%–2% with other artificial structures in combination with trees. In focus areas 2 and 3, SWP areas gradually decreased the year after the flood. In focus area 3, the overlap with the impact zones decreased as well, especially for driftwood only. This led to a 21% overlap with the impact zones of bridges in September 2021, and in June 2022, to an 18% overlap with the combined impact zone of bridges, trees, and other artificial structures. In focus area 2, about a week after the flood event, less than 2/3 of the stagnant water pools overlapped with impact zones. The impact zone of driftwood occupied the largest share with 21% followed by artificial structures other than bridges with 15%. In September 2021, stagnant water pools were predominantly located near bridges and artificial structures. In focus area 1, only one small stagnant water pool with a specific area of 13 m2/rkm was observed. It was not located within an impact zone.

The development of large stagnant water pools in focus area 3 is predominantly due to a former meandering channel section close to the River Rhine confluence (Fig. 7b, Jul 2021), which is still visible in the DEM (Digital Elevation Model). The area of stagnant water pools gradually declined with siltation in these areas, also leading to shoal formation (Fig. 5). In focus area 2, multiple stagnant water pools formed on the narrow floodplains after the flood event (Fig. 6). The specific area of stagnant water pools in September 2021 was dominated by the cut-off of an island, which formed in the meander bend after the flood event. In June 2022, a large erosional event at the bridge pier resulted in a cut-off (Fig. 7a), leading to a large stagnant water pool with an overlap with the impact zone of the bridges. Sediment samples by Gardner et al. revealed a high fine content and high liquidity in the pictured shoal [66]. Additionally, the DOPs in September 2021 show a high turbidity in the Ahr River compared to July 2021 and June 2022.

Visualization of two different processes in stagnant water pool development. a Focus area 2; formation of a stagnant water pool in the area of upstream erosion at a bridge due to the formation of a shoal upstream of a bridge pier. b Focus area 3; formation of a large stagnant water pool with overlap with former water courses still visible in the floodplain in July 2021 and siltation of area afterward. Sources of DOPs: [63, 67]

Discussion

Overall, the flood event of mid-July 2021 led predominantly to channel widening. Focus area 3 was the most active in terms of deposition and erosion (cf. Fig. 6) and lateral mobility (cf. Fig. 4). Focus area 2 was second most active in the formation of geomorphologic features, but least laterally active in response to natural and anthropogenic constraints. In focus area 1, the LMI is larger than in focus area 2. However, fewer stagnant water pools and mud deposits were observed in comparison.

Lateral geomorphologic shifts of the Ahr River

It is tested if the LMI reveals information about the lateral geomorphologic shifts of the Ahr River within three focus regions in length on the order of 1 to 5 rkm. Historic hand-sketched maps have larger uncertainties as their distance to the Rhine River increases. Uncertainties are determined to be 20 m at most [68]. Due to a lack of data for validation in the historic hand-sketched maps, accuracy could not be determined, as no on-site measurements from the time are available for comparison. However, it can be assumed that the historic LMI was rather overestimated as waterways were important strategic pathways for the military during that time [69] and rivers were likely sketched pronounced. The historic map resolution of 1.3 and 2.3 m only led to uncertainties of < 3% (possible difference in mapped area due to map resolution), but, nevertheless, the historic LMI should only be considered a reference value. It should also be considered that the historic LMI represents significantly larger time spans over which more geomorphological change would be expected, offering another explanation for the higher value. However, we lack information on the channel-forming discharges in the nineteenth century.

Large trees restricted visibility of riverbanks in the DOPs before the flood event. This may have resulted in an underestimate of the LMI from 1999 to 2019. If a bank coverage of 25% of both sides is considered as possible, representing about ¼ of a treetop canopy (around 1.5 m), an uncertainty of around 13% on average would be introduced (difference in width by channel length).

The LMI revealed varying lateral mobility across the three focus areas, with focus area 3 exhibiting the highest activity and focus area 2 the lowest which can be explained by differences in the valley morphology (Fig. 4). Focus area 3 is characterized by wide floodplain valleys, whereas focus area 2 is confined by steep hillslopes of 9.8° on average, and urban development in the floodplains. The floodplains in focus area 1 are wider than in focus area 2 but hardened due to urban development which restricts the lateral development of the river course (Fig. 1).

After the flood of mid-July 2021, the LMI quickly showed smaller values again (July 2021 to September 2021 and September 2021 to June 2022). As significantly smaller timespans are evaluated after the flood event than in between the historical maps (< 1 year vs. > 20 years), the historical comparison merely shows that the Ahr River had a different LMI in the past. Unfortunately, as the historic maps cover a large timespan, it is unknown if the high-energy flood of 1804 [70] is represented. Further, due to the long timespans in between historic maps, direct morphologic impacts by historic floods cannot be determined. From 1998 until 2021, where DOPs are available every 3 to 2 years, no comparable flood event happened [55]. Nevertheless, differences in the LMI in focus area 3 around the time of the flood versus historic and previous values are high, leaving no doubt that the flood of mid-July 2021 led to significant lateral geomorphological riverbed changes beyond the range of the last decade’s geomorphologic evolution (Fig. 4). In other words, the flood event represented a significant disruptor regarding lateral shifts in river course, and the LMI served as a quantifiable measure. In focus area 2, the LMI exceeded around the flood event the modern LMI values, but it did not exceed the historic value, which we explain by the hardened floodplains by anthropogenic use.

Morphologic features and overlap analysis

The accuracy of the mapping of driftwood, bridges, bridge piers, other artificial structures, mud deposits, stagnant water pools, shoals, artificial deposits, and rip-rap cannot be determined in this context, as it would only be possible with a comparison to field measurements. However, the underlying DOPs have a resolution of 0.4 m and 0.1 m, enabling accurate identification of these features and mapping to the image resolution. Also, discharges in all DOPs, except for the DOP taken on July 24, 2021, were very low (1–4 m3/s) (Table 2), and therefore, at comparable states. On July 24, 2021, discharges were between 8 and 10 m3/s, which is still around the average discharge, thus below bankfull, but elevated in comparison. As this DOP shows the most severe morphologic changes, we consider the visual limitation due to the slightly higher discharges small. Nevertheless, it likely leads to an underestimation of mud deposits and shoals. As the DOP on July 24, 2024 showed the most mud deposits (Fig. 6), inaccuracies do not change the trend and general statement. More shoals than on previous or later DOPs were observed in focus area 2 in the DOP on July 24, 2024 (Fig. 5). Values stayed the same in focus area 1 and slightly decreased in focus area 3. It is possible, that, due to an underestimation, those trends would be slightly different. As we do not have field measurements for comparison, determining the magnitude of the inaccuracies is not possible.

As the radius of 5 m for the impact zones is a methodological choice, and a simplification, the statistical relevance of causal relations (Fig. 6) needs to be tested. The distribution of the sub-selections of overlaps of mud deposits and stagnant water pools with impact zones differed significantly from the main population, with p-values of 0.002–0.004. As the sub-selected datasets thus are independent from the parent population, it can be assumed that overlaps hint toward a causal relation. Due to the simplification, our evaluation does not replace a description of individual morphological processes, as shown in Fig. 7.

For stagnant water pools, the overlap analysis showed by an increasing share of structures in September 2021 and June 2022 that driftwood was removed from the riverbed. Similar observations were made for mud deposits (Fig. 6). Areas of mud deposits decreased in September 2021 and increased in June 2022 again. Also, high turbidity in the Ahr River was noted in all three focus areas in September 2021 (Fig. 7). Turbidity, and thus, fine sediment dynamics may have been enhanced by ad hoc river management, repair, and cleanup measures. The slightly increasing narrowing of the river by shoals (Fig. 5) and decreasing relative river surface area (Fig. 4) hint toward sediment redeposition, too. The hypothesis of sediment redeposition due to cleanup measures is supported by artificial deposits and rip-rap appearing first in September 2021 in our imagery (Table 4). The change in overlap of mud deposits with impact zones of driftwood after the flood to impact zones of bridges and other artificial structures can be explained by cleanup of driftwood, which further supports our hypothesis. Example (a) (Fig. 7) shows how upstream erosion at a bridge was first masked by driftwood. After cleanup, during which one of the two bridges is removed, the formation of a shoal starting from a bridge can be observed. The high fines content and high liquidity of the shoal [67] support its recent formation.

In focus area 1, only one small stagnant water pool formed after the flood event and was quickly refilled with sediment. It is assumed that the straight river section enhanced erosion of a layer of softer bank material and restricted deposition due to high flow velocities. Further, we assume that the formation of stagnant water pools was restricted by hardened floodplains. Concluding, focus area 1 is the most anthropogenically restricted, although the valley width is larger than in focus area 2 (Table 1), which leads to the least formation of structures. Our findings are in good agreement with Hajdukiewicz et al. [6], who described similar restrictions for morphological development due to floodplain hardening, which hints toward a transferability.

Conclusion

The Lateral Mobility Index (LMI) was tested regarding the assessment of the significance of geomorphologic changes of the Ahr River during the 2021 flood event within three focus areas. Focus area 1 represents a 1-km-long relatively straight section with floodplains restricted by urban development. Focus area 2 is a 5-km-long section confined by bedrock in a natural preserve home to a small town and large bridges. Focus area 3 is a 3-km-long mostly natural section including the Rhine-Ahr confluence. The analysis covered a time span from 1998 to 2022 using digital orthophotos, and evaluated historic maps from 1803 to 1820 and 1843 to 1878 for comparison. The flood event in July 2021 yielded LMI values exceeding historic reference values by up to a factor of 3, confirming indeed a rare morphological disruption. Additionally, the evolution of mud deposits and stagnant water pools was assessed in relation to driftwood and infrastructure systems such as bridges and concrete bank structures. Mud deposits and stagnant water pools were clearly correlated to the flood event, serving as a second indicator of significant geomorphologic change. The evolution of mud deposits and shoals hinted at sediment deposition post-flood, likely resulting from river management, repair, and cleanup activities. Focus area 3 featured the largest LMI. Focus area 2 exhibited a limited lateral mobility and little formation of stagnant water pools due to confining narrow valleys. In focus area 1, the straight river section and hardened floodplains led to lateral erosion in some locations but reduced mud deposition and the formation of stagnant water pools. In summary, the following main conclusions can be drawn:

-

I.

The LMI offered a quantitative measure of lateral geomorphologic movements of the Ahr River during a severe flood event and succeeded to identify the flood as a major geomorphologic disruptor within the last 200 years.

-

II.

Differences in LMI between the three focus areas (each 1 to 5 rkm in length) were observed. Those can be explained by valley width, floodplain hardening, and urban development in a section. Hence, the LMI appears applicable in river sections of lengths on the order of 1 to 5 rkm.

-

III.

The impact of infrastructure elements, such as bridges and concrete structures on riverbanks, on the formation of mud deposits and stagnant water pools during and after the high-energy event of the mid-July 2021 flood, was superimposed by driftwood. Thus, it could not be determined whether driftwood accumulation or the presence of infrastructure or both governed local river changes. After cleanup, mud accumulation near infrastructure elements was observed, also leading to the formation of new stagnant water pools by cutting of bank erosions. Hardened floodplains, valley width, and historic channel courses further influenced the formation of stagnant water pools.

Overall, the flood event of mid-July 2021 was a significant morphologic driver in the area. A synthesis of our findings revealed mostly sediment deposition in the riverbed post-flood. This phase may still be ongoing and further river monitoring is recommended. We especially recommend to monitor the colmation, also in connection with biological parameters, as well as the ongoing lateral movement of the channel. Hydro-numerical modeling of sediment movements can predict future development to some degree, but more importantly, existing models for flood prediction need to be updated with new bathymetry data to display changes in flood-prone areas.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- DEM:

-

Digital Elevation Model

- DOP:

-

Digital orthophoto

- LMI:

-

Lateral Mobility Index

- NRW:

-

North Rhine-Westphalia

- rkm:

-

River kilometer

- RLP:

-

Rhineland-Palatinate

References

Wolman MG, Miller JP (1960) Magnitude and frequency of forces in geomorphic processes. J Geol 68:54–74. https://doi.org/10.1086/626637

Bertoldi W, Zanoni L, Tubino M (2010) Assessment of morphological changes induced by flow and flood pulses in a gravel bed braided river: The Tagliamento River (Italy). Geomorphology 114:348–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2009.07.017

Gupta S, Collier JS, Palmer-Felgate A et al (2007) Catastrophic flooding origin of shelf valley systems in the English Channel. Nature 448:342–345. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06018

Krapesch G, Hauer C, Habersack H (2011) Scale orientated analysis of river width changes due to extreme flood hazards. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci 11:2137–2147. https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-11-2137-2011

Suchodoletz H, Pohle M, Khosravichenar A et al (2022) The fluvial architecture of buried floodplain sediments of the Weiße Elster River (Germany) revealed by a novel method combination of drill cores with two-dimensional and spatially resolved geophysical measurements. Earth Surf Process Landforms 47:955–976. https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.5296

Hajdukiewicz H, Wyżga B, Mikuś P et al (2016) Impact of a large flood on mountain river habitats, channel morphology, and valley infrastructure. Geomorphology 272:55–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2015.09.003

Death RG, Fuller IC, Macklin MG (2015) Resetting the river template: the potential for climate-related extreme floods to transform river geomorphology and ecology. Freshw Biol 60:2477–2496. https://doi.org/10.1111/fwb.12639

Lehmkuhl F, Schüttrumpf H, Schwarzbauer J et al (2022) Assessment of the 2021 summer flood in Central Europe. Environ Sci Eur. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-022-00685-1

Schüttrumpf H, Brüll C, Klopries E-M et al (2022) Das Hochwasser 2021 in Nordrhein-Westfalen und Rheinland-Pfalz: Beobachtungen und Erfahrungen. In: Institut für Siedlungswasserwirtschaft der RWTH Aachen University (ed) Wasserwirtschaft im Klimawandel: digitale 55. Essener Tagung für Wasserwirtschaft, vol 254. Gesellschaft zur Förderung des Instituts für Siedlungswasserwirtschaft an der RWTH Aachen e.V, Aachen

Schüttrumpf H, Birkmann BC et al (2022) Die Flutkatastrophe 2021 im Ahrtal und ihre Folgen für den zukünftigen Hochwasserschutz. Wasser und Brunnen 14:43–49

Schüttrumpf H, Birkmann J, Brüll C et al (2022) Herausforderungen an den Wiederaufbau nach dem Katastrophenhochwasser 2021 in der Eifel. Nachhaltigkeit im Wasserbau - Umwelt, Transport, Energie. Dresdner Wasserbauliche Mitteilungen 5–16

Lehmkuhl F, Weber A, Esser V et al (2022) Fluviale Morphodynamik und Sedimentkontamination bei Extremereignissen: Das Juli-Hochwasser 2021 im Inde-Einzugsgebiet (Nordrhein-Westfalen). Korrespondenz Wasserwirtschaft 422–427

Junghänel T, Bissolli P, Daßler J et al (2021) Hydro-klimatologische Einordnung der Stark-und Dauerniederschläge in Teilen Deutschlands im Zusammenhang mit dem Tiefdruckgebiet „Bernd “vom 12. bis 19. Juli 2021

Schäfer A, Mühr B, Daniell J et al (2021) Hochwasser Mitteleuropa, Juli 2021 (Deutschland) : 21. Juli 2021—Bericht Nr. 1 „Nordrhein-Westfalen & Rheinland-Pfalz”. Karlsruher Institut für Technologie (KIT)

Mohr S, Ehret U, Kunz M et al (2023) A multi-disciplinary analysis of the exceptional flood event of July 2021 in central Europe - Part 1: Event description and analysis. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci 23(2):525–551. https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-23-525-2023

Tradowsky JS, Philip SY, Kreienkamp F et al (2023) Attribution of the heavy rainfall events leading to severe flooding in Western Europe during July 2021. Clim Change. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-023-03502-7

BMI und Bundesfinanzministerium (2021) Zwischenbericht zur Flutkatastrophe 2021: Katastrophenhilfe, Soforthilfen und Wiederaufbau

Lehmkuhl F, Keßels J, Schulte P et al (2022) Beispiele für morphodynamische Prozesse und Verlagerungen in Folge des Hochflutereignisses 2021 im Ahrtal. Wasser Abfall 24:40–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s35152-022-1349-7

Enzmann F, Kersten M, Wehniger A (2022) GIS-gestützte Modellierungsansätze zur Initiierung von Massenbewegungen. In: Forschungsstelle Rutschungen an der Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz (ed) 20. Weiterbildungsseminar: Fachtagung Rutschungen. Folgen - Forschung - Praxis, pp 20–25

Koks EE, van Ginkel KCH, van Marle MJE et al (2022) Brief communication: critical infrastructure impacts of the 2021 mid-July western European flood event. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci 22:3831–3838. https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-22-3831-2022

Wehinger A, Rogall M, Enzmann F (2022) Massenbewegungen im Ahrtal als Folge des Starkregens und der Flut—Eine erste Bestandsaufnahme. In: Forschungsstelle Rutschungen an der Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz (ed) 20. Weiterbildungsseminar: Fachtagung Rutschungen. Folgen - Forschung - Praxis, pp 10–18

Dietze M, Bell R, Ozturk U et al (2022) More than heavy rain turning into fast-flowing water—a landscape perspective on the 2021 Eifel floods. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci 22:1845–1856. https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-22-1845-2022

Nichols E, Lemnitzer A, Stark N et al (2022) Impact of 2021 Western European Flooding on Geo-Structures. In: Liu R, Mulea CC, Parfit MK et al (eds) Forensic Engineering 2022. American Society of Civil Engineers, Reston, VA, pp 322–330

Lemnitzer A, Stark N, Gardner M, George M, Nichols E (2022) Geotechnical Reconnaissance of the 2021 Western European Floods. GEER Association (Report 76)

Korswagen PA, Harish S, Oetjen J et al (2022) Post-flood field survey of the Ahr Valley (Germany): building damages and hydraulic aspects. Delft University of Technology

Burghardt L, Schüttrumpf H, Wolf S et al (2022) Analyse der Schäden an Brückenbauwerken in Folge des Hochwassers 2021 an der Ahr. Wasser Abfall 24:12–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s35152-022-1346-x

Szymczak S, Backendorf F, Bott F et al (2022) Impacts of heavy and persistent precipitation on railroad infrastructure in July 2021: a case study from the Ahr Valley, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. Atmosphere 13:1118. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos13071118

Brüll C, Esser V, Lehmkuhl F et al (2022) Geomorphologen und Wasserbauingenieure betrachten die Auswirkungen des Juli-Hochwassers. In: im Auftrag des Rektors (ed) RWTH Themen: Hochwasser—Beiträge zu Risiken, Folgen und Vorsorge. Forschungsmagazin, Aachen, pp 12–17

Dietze M, Ozturk U (2021) A flood of disaster response challenges. Science 373:1317–1318. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abm0617

Michalková M, Piégay H, Kondolf GM et al (2011) Lateral erosion of the Sacramento River, California (1942–1999), and responses of channel and floodplain lake to human influences. Earth Surf Process Landforms 36:257–272. https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.2106

Kesel RH, Dunne KC, McDonald RC et al (1974) Lateral erosion and overbank deposition on the Mississippi River in Louisiana caused by 1973 flooding. Geology 2:461. https://doi.org/10.1130/0091-7613(1974)2%3C461:LEAODO%3E2.0.CO;2

Nones M, Guo Y (2023) Can sediments play a role in river flood risk mapping? Geoenviron Disasters, Learning from selected European examples. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40677-023-00250-9

Reisenbüchler M, Bui MD, Skublics D et al (2019) An integrated approach for investigating the correlation between floods and river morphology: a case study of the Saalach River, Germany. Sci Total Environ 647:814–826. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.08.018

Kundzewicz ZW, Lugeri N, Dankers R et al (2010) Assessing river flood risk and adaptation in Europe—review of projections for the future. Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Change 15:641–656. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-010-9213-6

Weber A, Wolf S, Becker N et al (2023) The risk may not be limited to the flooding—polluted high flood sediments pose a health threat to the unaware public. Environ Sci Eur. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-2652609/v1

Crawford SE, Brinkmann M, Ouellet JD et al (2021) Remobilization of pollutants during extreme flood events poses severe risks to human and environmental health. J Hazard Mater 421:126691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.126691

Schwanen C, Bellanova P, Schwarzbauer J (2022) The 2021 Flood Disaster in Germany – Distribution, remobilization and accumulation of organic pollutants along the natural floodplains of the Rur river, EGU General Assembly 2022, Vienna, Austria, 23–27 May 2022, EGU22-12558, https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-egu22-12558

Dubuis R, de Cesare G (2023) The clogging of riverbeds: a review of the physical processes. Earth Sci Rev 239:104374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2023.104374

Castro JM, Thorne CR (2019) The stream evolution triangle: Integrating geology, hydrology, and biology. River Res Applic 35:315–326. https://doi.org/10.1002/rra.3421

Howard AD, Dietrich WE, Seidl MA (1994) Modeling fluvial erosion on regional to continental scales. J Geophys Res 99:13971–13986. https://doi.org/10.1029/94JB00744

Lane SN, Richards KS (1997) Linking river channel form and process: time, space and causality revisited. Earth Surf Process Landforms 22:249–260. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1096-9837(199703)22:3%3c249:AID-ESP752%3e3.0.CO;2-7

Polvi LE, Lind L, Persson H et al (2020) Facets and scales in river restoration: nestedness and interdependence of hydrological, geomorphic, ecological, and biogeochemical processes. J Environ Manage 265:110288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.110288

Peters J, Wendling K (2005) Fließgewässertypen (biozönotisch): hydrologischer Atlas Rheinland-Pfalz. Blatt 41. Landesamt für Umwelt, Wasserwirtschaft und Gewerbeaufsicht Rheinland-Pfalz, Mainz

Vélez Pérez M, Wolf S, Klopries E (2023) Quantifizierung des Einflussesder Landnutzung an der Ahr aufdas Abflussverhalten. Korrespondenz Wasserwirtschaft 16:435–441. https://doi.org/10.3243/kwe2023.07.004

ESTAT (2020) Countries, 2020—Administrative Units—Dataset. https://gisco-services.ec.europa.eu/distribution/v2/countries/download/. Accessed 27 Oct 2023

Landesamt für Vermessung und Geobasisinformation RLP (2018) Verwaltungsgrenzen im Vektorformat: Landesgrenze. Datenlizenz Deutschland—Namensnennung—version 2.0. http://geo5.service24.rlp.de/wfs/verwaltungsgrenzen_rp.fcgi? Accessed 27 Oct 2023

Geofabrik GmbH (2018) is_osm_places_a_free_1. CC BY-SA 2.0. download.geofabrik.de. Accessed 19 Oct 2020

Geofabrik GmbH (2018) gis_osm_waterways_free_1. CC BY-SA 2.0. download.geofabrik.de. Accessed 19 Oct 2020

LfU RLP (2022) 4-Wasserstand und Anschlaglinie. E-Mail

Esri Deutschland (2023) Flussgebietseinheiten und Einzugsgebietsgrenzen Deutschland. https://opendata-esri-de.opendata.arcgis.com/maps/esri-de-content:flussgebietseinheiten-und-einzugsgebietsgrenzen-deutschland/about. Accessed 27 Oct 2023

Geofabrik GmbH (2018) gis_osm_buildings_a_free_1. CC BY-SA 2.0. download.geofabrik.de. Accessed 19 Oct 2020

Landesbetrieb Information und Technik Nordrhein-Westfalen (2023) Digitales Geländemodell—Gitterweite 1 m. Datenlizenz Deutschland—Zero. https://www.opengeodata.nrw.de/produkte/geobasis/hm/dgm1_xyz/. Accessed 27 Oct 2023

LVERMGEO (2018/2019) DGM 1 m Gitterweite ASCII (X,Y,Z) 135 Kacheln (1x1 km), Ahrtal Befliegung: 2018/ 2019. Datenbereitstellung am 2. Februar 2022

LVermGeoRP (2023) Open Data—Freie Daten und Dienste der Vermessungs- und Katasterverwaltung Rheinland-Pfalz: Digitale Orthophotos (DOP), Luftbild historisch (zeitvariabel). dl-de/by-2–0, https://www.geoportal.rlp.de/mapbender/php/wms.php?layer_id=74145&VERSION=1.1.1&withChilds=1. https://lvermgeo.rlp.de/de/geodaten-geoshop/opendata/. Accessed 23 Oct 2023

SGD Nord (2024) Pegel Altenahr. https://geodaten-wasser.rlp-umwelt.de/wasserstand/2718040300/stammdaten. Accessed 26 Jan 2024

SGD Nord (2024) Pegel Bad Bodendorf. https://geodaten-wasser.rlp-umwelt.de/wasserstand/2718060700/stammdaten. Accessed 26 Jan 2024

Richard GA, Julien PY, Baird DC (2005) Case study: modeling the lateral mobility of the Rio Grande below Cochiti Dam, New Mexico. J Hydraul Eng 131:931–941. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9429(2005)131:11(931)

Helfer M (2009) Die Tranchot-Müffling-Karte (1801–1828). In: Helfer M (ed) GR-Atlas—Atlas der Großregion SaarLorLux: PAPER SERIES. Paper 12-2009. Institute of Geography and Spatial Planning—UR IPSE University of luxembourg Masion des Science Humaines, Esch-Belval

Bezirksregierung Köln (2024) 1836–1850: Preußische Kartenaufnahme 1 : 25000; Uraufnahme: Die preußische Uraufnahme war das erste flächendeckend einheitliche Kartenwerk im Maßstab 1 : 25 000 für das Staatsgebiet des Königreichs Preußen. https://orbilu.uni.lu/bitstream/10993/24542/1/GR-ATLAS_12.pdf. Accessed 16 Nov 2023

Pucci A, Eickmeier D, Sousa HS et al (2023) Fragility analysis based on damaged bridges during the 2021 flood in Germany. Appl Sci 13:10454. https://doi.org/10.3390/app131810454

Fazelpoor K, Martínez-Fernández V, García de Jalón D (2021) Exploring the hydromorphological response to human pressure in Tagus River (1946–2014) by complementary diagnosis. CATENA 198:105052. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2020.105052

Wolf S, Burghardt L, Stark N et al (2023) Historic changes in river course and morphodynamics of the Ahr river within geological and anthropogenic boundaries

Andreas Becker (2022) LVG-43_26 722–1.5; Sonderbefliegung Hochwasser Ahrtal; Freischaltung WMS DOP20; RWTH Aachen; Re: Anfrage Geodaten NRW. E-Mail

Rey D, Neuhäuser M (2011) Wilcoxon-signed-rank test. In: Lovric M (ed) International encyclopedia of statistical science. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp 1658–1659

LfU RLP (2023) Analysen und Messwerte: Download-Assistent Analysen und Messwerte Wasser. https://geoportal-wasser.rlp-umwelt.de/servlet/is/1500/. Accessed 24 Oct 2023

Gardner M, Stark N, Lemnitzer A et al (2023) Geotechnical and geoenvironmental properties of the Ahr River, Germany, after the 2021 Western European Flood. Designsafe-CI

LVermGeoRP (2023) Open Data—Freie Daten und Dienste der Vermessungs- und Katasterverwaltung Rheinland-Pfalz: Digitale Orthophotos (DOP), Digitale Ortophotos, Bodenauflösung 40 cm. dl-de/by-2-0. https://www.geoportal.rlp.de/mapbender/php/wms.php?layer_id=61676&VERSION=1.1.1. https://lvermgeo.rlp.de/de/geodaten-geoshop/opendata/. Accessed 23 Oct 2023

Nilson E (2006) Räumlich-strukturelle und zeitlich-dynamische Aspekte des Landnutzungswandels im Dreiländereck Belgien-Niederlande-Deutschland: Eine Analyse mittels eines multitemporalen, multifaktoriellen und grenzübergreifenden Geographischen Informationssystems. Aachen, Techn. Hochsch., Diss., 2006

Helfer M (ed) (2009) GR-Atlas—Atlas der Großregion SaarLorLux: PAPER SERIES. Paper 12-2009(12)

Roggenkamp T, Herget J (2014) Reconstructing peak discharges of historic floods of the river Ahr, Germany. Erdkunde 68:49–59. https://doi.org/10.3112/erdkunde.2014.01.05

LVermGeoRP (2023) Open Data—Freie Daten und Dienste der Vermessungs- und Katasterverwaltung Rheinland-Pfalz: Historische Karten, Kartenaufnahme der Rheinlande durch Tranchot und von Müffling (1803–1820). dl-de/by-2-0. https://www.geoportal.rlp.de/mapbender/php/wms.php?layer_id=49369&REQUEST=GetCapabilities&VERSION=1.1.1&SERVICE=WMS&withChilds=1. https://lvermgeo.rlp.de/de/geodaten-geoshop/opendata/. Accessed 23 Oct 2023

LVermGeoRP (2023) Open Data—Freie Daten und Dienste der Vermessungs- und Katasterverwaltung Rheinland-Pfalz: Historische Karten, Preußische Kartenaufnahme 1:25 000 (1843–1878)—Uraufnahme. dl-de/by-2–0, https://www.geoportal.rlp.de/mapbender/php/wms.php?layer_id=61676&VERSION=1.1.1. https://lvermgeo.rlp.de/de/geodaten-geoshop/opendata/. Accessed 23 Oct 2023

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank the editor and anonymous reviewers who improved the manuscript. They further thank the Landesamt für Vermessung und Geobasisinformation Rheinland-Pfalz, especially Andreas Becker, and the Landesamt für Vermessung und Geobasisinforamtion Rheinland-Pfalz, especially Jan Paul Krüger, for providing us with geodata. NS would like to acknowledge funding by the National Science Foundation and support by the NSF-funded Geotechnical Extreme Event Reconnaissance (GEER) Association, GEER co-team leaders Anne Lemnitzer (UC Irvine) and Michael Gardner (UC Davis), and all GEER team members who participated and contributed to the reconnaissance mission

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This study was supported by Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung, 01LR2102A, 01LR2102A, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, project number 496274914, and NSF GEER Association, CMMI1826118 and CMMI RAPID 2213715/2213768/2213714.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NS and SW conceptualized the study. SW wrote the first draft of the manuscript. NS assisted with manuscript editing. All authors contributed on specific aspects of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wolf, S., Stark, N., Holste, I. et al. Evaluation of the high-energy flood of mid-July 2021 as a morphologic driver in the anthropogenically developed Ahr Valley, Germany, in interaction with infrastructures. Environ Sci Eur 36, 54 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-024-00860-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-024-00860-6