Abstract

Pregnancy is a period of significant physical and psychological changes. Pregnant women often struggle with poor sleep quality which can increase the risk of developing depression and anxiety. Additional factors can affect sleep quality and vice versa. We focused on an understudied topic: pregnant women`s expectations about how their infant will sleep. This study aims to describe the potential correlates and predictors of women`s sleep quality and their expectations about child sleep in a broader context. In total, 250 women participated in the research. Participants completed questionnaires PSQI, MEQ, DASS-21 and BISQ-R. To verify the set aims, we used Pearson’s correlation coefficient, t-test and general linear model (GLM), including methods for determining the effect size (Hedges’ g, r2, ε2). The results showed that sleep quality is related to circadian preference, depression, anxiety and stress. Women with poor sleep quality were more evening type and scored higher on these variables. Anxiety, circadian preference and the week of pregnancy were the most significant predictors of sleep quality. Women with at least one child and women who did not prepare for childbirth and motherhood and had not encountered information about a child’s sleep scored higher in BISQ-R. A hypothesis can be put forward that sufficient information before childbirth and earlier maternal experiences can affect expectations about a child’s sleep. This hypothesis would need to be verified in future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pregnancy is a period of significant physical and psychological changes and difficulties. Researchers debate mainly about depression, anxiety and disturbed sleep. Nearly 46% of pregnant women experience poor sleep quality during pregnancy (Sedov et al., 2018), mainly caused by the inability to find a comfortable position, frequent urination, lower back pain or gastroesophageal reflux disorder (Mindell et al., 2015; Silvestri & Aricò, 2019). Sleep quality is usually defined as an aggregate of several variables, such as sleep duration, continuity or efficiency. Hutchison et al. (2012) demonstrated that pregnant women have a shorter total sleep time than before pregnancy. It has been found that hormonal modifications can affect sleep length, quality and physiology (Silvestri & Aricò, 2019). Most studies focus on the subjective assessment of sleep quality using validated questionnaires, most commonly the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). Other studies also use objective measurements using actigraphs or polysomnography (PSG). Studies that used objective sleep measures support findings of poor sleep quality among pregnant women. Pregnant women have lower sleep efficiency, more frequent night-wakings and longer night-wakings (WASO) and spend more time in light sleep and less time in deep sleep and REM sleep (Tsai et al., 2016; Wilson et al., 2011).

Poor sleep quality and hormonal and physiological changes can act as a triggers for sleep disorders (Moghadam et al., 2021). Some pregnant women may start to snore more (Facco et al., 2010; Hutchison et al., 2012) or directly suffer from obstructive sleep apnea (Silvestri & Aricò, 2019). Some women also suffer from restless legs syndrome or insomnia (Kaya & Koçak, 2023; Silvestri & Aricò, 2019). Due to the high prevalence of sleep disorders and poor sleep quality during pregnancy, more space should be devoted to the complaints of pregnant women about their sleep discomfort (Silvestri & Aricò, 2019). Poor sleep can affect the health of both the mother and the foetus. Disrupted sleep during pregnancy has been linked to negative obstetric outcomes, including pre-eclampsia, gestational hypertension, gestational diabetes mellitus, preterm labour and increased risk of caesarean delivery (Lu et al., 2021).

Depression prevalence is generally higher in women (Kuehner, 2017). During pregnancy, the prevalence of depression is around 21% (Yin et al., 2021).It turns out that it is necessary to take into account the week of pregnancy and the mother’s statute (primiparous or multiparous mother) (Canário & Figueiredo, 2017). Anxiety disorders are also common during pregnancy, with a prevalence ranging from 1 to 20%. The specific prevalence depends on the type of anxiety disorder (Viswasam et al., 2019). A specific dimension within the spectrum of pregnancy-related anxiety represents Tocophobia. Tocophobia can be referred to as ‘Fear of Childbirth (FOC)’ or ‘an unreasoning dread of childbirth, which is experienced by approximately 14% of women (O’Connell et al., 2017). Research on sleep in pregnant women’s mental health shows that poor sleep quality in pregnant women is concurrently and prospectively associated with higher depressive and anxiety symptoms during pregnancy (Alder et al., 2007; van de Loo et al., 2018; Volkovich et al., 2016).

As with sleep problems, the prevalence of psychological problems may vary depending on the stage of pregnancy. The consensus is not clear, however, as studies differ in their conclusion. There has been an increase in depression or anxiety symptoms during pregnancy. On other occasions, the results were the opposite (van de Loo et al., 2018). Overall, the results of the studies describe a striking trend: higher sleep problems during pregnancy increase the potential risk of developing depressive or anxiety symptoms during pregnancy, which in turn increases the risk of developing postpartum depression (Okun et al., 2013; Tomfohr et al., 2015; van de Loo et al., 2018). It is important to note that poor sleep quality, stress, depression and anxiety during pregnancy can affect adverse obstetric outcomes and the development of the foetus and the child’s mental and physical health, including early brain development (Alder et al., 2007; Dean et al., 2018; Graignic-Philippe et al., 2014).

Other factors, such as circadian preference, also contribute to the quality of sleep and the occurrence of depressive or anxiety disorders. It turns out that pregnant women with an evening preference (so-called night owls) have a higher risk of developing depressive symptoms not only during pregnancy. They are also highly predisposed to postnatal depression (Obeysekare et al., 2020). Pregnant evening-type women report more anxiety symptoms (Ashi et al., 2022), and sleep problems, including trouble falling asleep, poor sleep quality and daily tiredness than morning-type women, even after controlling for sleep duration and sleep deprivation (Merikanto et al., 2017).

Another factor influencing maternal sleep quality and mental health is infant sleep quality. The quality of an infant’s sleep affects many associated factors on the parent’s side (fatigue, depression, anxiety, well-being, stress and much more) (Bayer et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2021; Muscat et al., 2014; Park et al., 2013; Stremler et al., 2020). Pregnant women form determinate ideas, however, about how their infant will sleep. These ideas stem from cultural and social sources that represent a relevant role in their expectations (Ball, 2003; Dias et al., 2018). The problem arises when these expectations differ from reality. Unrealistic expectations regarding infant sleep can be significant predictors of a mother’s sleep quality or mental health (Eastwood et al., 2012; Giallo et al., 2011;). For example, it has been found that a significant disparity between expected and actual sleeping arrangements is linked to a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms after childbirth, regardless of the actual sleep patterns (Chénier-Leduc et al., 2023). However, mother`s ideas about their child`s sleep are not the frequent focus of studies. Therefore, we asked ourselves several research questions: Is the quality of a woman’s sleep during pregnancy related to her expectations about the child`s sleep? Is there a relationship between sociodemographic variables (e.g., age, number of children, seeking information about infant sleep) and expectations about child sleep? Which of the variables predicts this expectation?

As can be seen, the area of interest of researchers among pregnant women focuses mainly on depression, anxiety and sleep quality. It turns out that these variables can interact with each other (Pauley et al., 2020). To the best of the authors’ knowledge, current research does not sufficiently address the potential correlates and predictors of maternal sleep quality and their expectations about child sleep in a broader context. We therefore consider our research to be pilot in this area. We aimed to map the sleep quality, depression, anxiety and stress of women in the context of circadian preferences, number of children, level of education, preparation for childbirth and motherhood. We were looking for an answer to the question of which variables can be potential predictors of sleep quality and, in particular, expectations about how the child will sleep after birth and vice versa.

Materials and methods

Study sample

The data were collected in May and June 2022 as part of the research "Children’s sleep—mothers’ expectations vs reality" conducted at the Department of Psychology, Faculty of Arts, Palacký University in Olomouc, Czech Republic. The research was approved by the Research Ethics Panel of the Faculty of Arts of the Palacký University in Olomouc, Czech Republic (protocol number 04/2022). The study protocol followed international ethical standards (APA, 2002). All participants filled out online questionnaires battery including Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), Morningness-eveningness Questionnaire (MEQ), Depression and Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21), Brief Infant Sleep Questionnaire-R short version (BISQ-R) and socio-demographic information (age, week of pregnancy, number of children, highest level of education and information regarding preparation for childbirth and child care). A total of 296 women participated in the research. We excluded women who were not in the third trimester and not currently pregnant (e.g., they were postpartum). Based on these exclusion criteria and incomplete questionnaires (incorrect or missing values that were not replaced by the multiple imputation method), we excluded 46 women. We included in the analysis women who were currently in the third trimester of pregnancy, had no serious physical or mental illness, and correctly filled out a series of questionnaires. There were 250 women in total.

Questionnaires’ battery

We used the following information to map socio-demographic data. The participants numerically indicated their age and the week of pregnancy they were currently in. They also mentioned the highest level of education achieved (Primary school, Secondary education apprenticeship certificate, Secondary school with school-leaving exams, University). Since these items were not mandatory, the participants could also choose the form of the answer: "I don’t want to answer". We also asked questions from which women could choose from several options. The first question was focused on preparation for childbirth during pregnancy. The participants could choose from the following options (it was possible to select several options at the same time): 1) Yes, I completed a prenatal preparation course 2) Yes, I use the services (counselling) of a midwife 3) Yes, I use the services (counselling) of a doula 4) Yes, I use the services (consultation) of a lactation consultant 5) Yes, I look for the information myself (books, Internet sources…) 6) Yes, I use other services/I prepare differently 7) I have not used any method of preparation yet, but I plan to use it, and 8) I have not used any method of preparation yet, and do not plan to use it. The last question had a choice of YES or NO. The question was whether they encountered information about children’s sleep during the preparations.

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index was created by Buysse et al., in 1989. This questionnaire assesses an individual’s sleep quality over the last month. The measurement consists of 19 items evaluated from 0 to 3 points. The PSQI work with seven components (Subjective Sleep Quality, Sleep Latency, Sleep Duration, Sleep Efficiency, Sleep Disturbance, Medication Use, and Sleep Dysfunctions). These components add up to a total score ranging from 0 to 21 points. The higher the score, the worse the sleep quality. The authors evaluate poor sleep quality if the total score amounts to six or more points (Buysse et al., 1989). We used the Czech version of the questionnaire, which has good reliability and validity (Manková et al., 2021).

The Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale consists of three self-report scales designed to measure the emotional states of depression (D), anxiety (A) and stress (S). DASS was created by Lovibond S. H. and Lovibond P. F. in 1995 (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995). In the short version with 21 questions (DASS-21), participants choose answers on a 4-point scale (0-never to 3- almost always). Each of the three DASS-21 scales contains seven items, divided into subscales with similar content. Scores for depression, anxiety and stress are calculated by summarizing the scores for the relevant items multiplied by two. Recommended cut-off scores are as follows (Table 1). We used the the Czech version of DASS-21 translated by Vilimovský and Kučera (n.d.), which is available on the official website of the questionnaire.

In 1976, Horne and Östberg developed the Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire to help determine circadian preferences. Each of the 19 items tracks the respondent’s preference while performing various activities. Five questions have a time graph format, and the remaining 14 questions offer the respondent a choice between 4 answers scored 1–4 or 0–6 points. 16 to 86 points can be achieved in the questionnaire (16 to 30 definitely evening type, 31 to 41 moderately evening type, 42 to 58 neither or intermediate type, 59 to 69 moderately morning type, and 70 to 86 definitely morning type) (Horne & Östberg, 1976). In the research, we used the Czech version of the questionnaire, which has good reliability (Fárková et al., 2020).

The Brief Infant Sleep Questionnaire was created by Avi Sadeh in 2004. In 2019, the questionnaire was revised by Mindell and colleagues. The questionnaire has a full version and a short form. We used the revised BISQ-R short version with 19 items in our research. The questionnaire works with three subscales: Infant Sleep (IS), Parent Perception (PP), and Parent Behavior (PB) subscales. A total score is calculated as the average of all subscale scores (0 to 100 points). Higher scores denoting better infant sleep quality and more positive parent perception and behavior influence infant sleep. The total score represents an infant’s level of sound and independent sleep (Mindell et al., 2019; Sadeh, 2004). Permission was granted by Erin Leichman and colleagues to translate the BISQ-R short version from English to Czech according to the rules of double-back translation.

Statistical analysis

We used the freely available software G*power (Faul et al., 2007, 2009) to determine the minimal sample size while maintaining the medium effect size. For all types of statistical analyses (correlations, t-test, general linear model), our sample size of n = 250 was sufficient. Statistical significance was accepted at the level p < 0.05. We used correction for multiple testing (Bonferroni correction) to reduce the probability of Type I error. We used TIBCO Statistica13 software for statistical data analysis, version 13.4.0.14 (TIBCO Software Inc., Palo Alto, USA). We evaluated the data distribution based on diagnostic plots and using the Shapiro–Wilk test. All variables exhibited a non-normal distribution and the Box-Cox transformation was applied to transform them towards normality (Box & Cox, 1964). After data transformation, we used the t-test to calculate the difference between good and poor sleepers (as measured by the total score in the PSQI) and between the groups of primiparous mothers and mothers with at least one child. We used Pearson’s correlation coefficient to examine correlations between questionnaire scores, age and week of pregnancy. The effect size was determined using Hedges’ g and Coefficient of determination (r2). A frequently used evaluation of the magnitude of the r coefficient is as follows: r = 0.71–1 → large effect, r = 0.31–0.70 → medium effect, r = 0.10–0.30 → small effect (Cohen, 1988). We examined other relationships using standard linear models (GLM). We were interested in determining potential predictors of sleep quality in women. We were also interested in women’s expectations regarding the sleep of their unborn child. Pregnant women answered the questions in BISQ-R with an idea about what the child’s sleep could be after the elapse of six weeks of age. The effect size was evaluated using eta squared (ε2) for nominal and ordinal variables appraised using the following criteria: 0.01 < 0.06 (as small effect), 0.06 < 0.14 (as moderate effect), and ≥ 0.14 (as large effect) (Richardson, 2011). We determined the internal consistency of the questionnaire using Cronbach’s alpha (Cronbach, 1951). A reliability statistic of 0.70 was considered acceptable and under 0.60 was not (Field, 2013).

Results

Descriptive statistic

A total of 250 women in the third trimester were included in this study. The mean age was 29 years (SD = 3.83), and the mean week of pregnancy was 34.17 weeks (SD = 3.59). Circadian preferences were not normally distributed in our sample. Only eight women scored as moderately evening, and one as definitely an evening type. Morning types predominated (definitely morning n = 19, moderately morning n = 114). The remaining 108 women (43%) were neither type. Most women (n = 146, 59%) had obtained a university education. A total of 162 women (65%) were primiparous mothers, and 79 women already had one child. Nine women reported having two or more children. Almost all women in our group (91%) were preparing for childbirth and motherhood. Most women used self-study (43%), and 24% took an antenatal course. Some pregnant women (13%) also used the care and advice of a lactation consultant, doula or midwife. The remaining women reported (11%) that they were preparing, but in a different way than stated. Additionally, 76% of women reported that they encountered information about baby sleep during these preparations. A descriptive statistic of the monitored variables can be found in Table 2. We tested the internal consistency of individual questionnaires or their subscales using Cronbach’s alpha. The results showed adequate reliability in MEQ α = 0.78, PSQI α = 0.73, Depression by DASS-21 α = 0.85, Anxiety by DASS-21 α = 0.76, and Stress by DASS-21 α = 0.84. The achieved score α = 0.54 in the BISQ-R questionnaire is debatable.

Relationship between variables

Sleep quality (measured by PSQI total score) showed a significant association with MEQ total score (r = -0,2, t = -3,23, p < 0.01; r2 = 0.04), depression (r = 0.35; t = 5.81, p < 0.001; r2 = 0.12), anxiety (r = 0.38, t = 6.42, p < 0.001; r2 = 0.14) and stress (r = 0.36; t = 6.03, p < 0.001; r2 = 0.13). In other words, the worse the women’s sleep quality, the higher they scored on the depression, anxiety and stress scales of the DASS-21 questionnaire and lower in MEQ (they were more evening types). We also found a significant correlation between circadian preference (MEQ total score) and depression (r = -0.13, t = -2.12, p < 0.05, r2 = 0.02), MEQ total score and anxiety (r = -0.13, t = -1.98, p < 0.05, r2 = 0.02), depression and anxiety (r = 0.57; t = 10.93, p < 0.001; r2 = 0.33), depression and stress (r = 0.67; t = 14.28, p < 0.001; r2 = 0.45) and anxiety and stress (r = 0.58; t = 11.21, p < 0.001; r2 = 0.34). Logically, a significant relationship was also established between the total score of the BISQ-R questionnaire and its three subscales, Infant sleep, Parent perception and Parent behavior. The results showed a significant relationship between age and circadian preferences (MEQ total score) (r = 0.13, t = 1.99, p < 0.05, r2 = 0.02), depression (r = -0.16, t = -2.58, p < 0.05, r2 = 0.03), anxiety (r = -0.24; t = -3.94, p < 0.001; r2 = 0.06), stress (r = -0.16, t = -2.51, p < 0.05, r2 = 0.02), BISQ-R (r = 0.14, t = 2.27, p < 0.05, r2 = 0.02) and Infant sleep (r = 0.16, t = 2.52, p < 0.05, r2 = 0.03). It means the older the women, the more morning types they were, the less depression, anxiety and stress they felt and the more optimistic expectations about infant sleep they had. Correction for multiple testing revealed a non-significant relationship between MEQ total score and anxiety, borderline significance between MEQ total score and age, shown in Table 3.

Differences between good and poor sleepers and primiparous mothers and mothers with children

As shown in Table 4, women with poor sleep quality score higher on all scales of the DASS-21 with a medium to large effect level. A statistically significant difference between groups was also shown for circadian preference. We also searched for differences between primiparous mothers and women with at least one child. The difference was evident in age, the BISQ-R questionnaire, including its subscales (IS, PP, PB). Women who already have at least one child were older and expected better overall sleep for their child (BISQ-R, IS). Their assumptions about difficulties resulting from children’s sleep are more optimistic (PP) (Table 5). The founded differences remained significant even after correction for multiple testing.

Predictors of sleep quality and women’s expectations

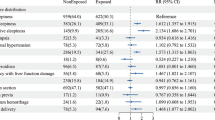

Sleep quality was predicted by a week of pregnancy (β = 0.12, t = 2,09, p < 0.05), circadian preference (β = -0.13, t = -2.23, p < 0.05) and anxiety (β = 0.21, t = 2.76, p < 0.01). This determined model explains 19% (F = 6.71, p < 0.001) of the variance in sleep quality. We determined expectations regarding infant sleep using the BISQ-R questionnaire and its subscales (Fig. 1). The most significant predictor was having a child (ε2 = 0.18). The week of pregnancy and stress showed a small effect size (ε2 = 0.02). The predictor of attainment education had a moderate effect size (ε2 = 0.09). Although preparation for childbirth and motherhood, equally obtaining information about the child’s sleep, did not appear to be significant factors of maternal expectation, the t-test revealed a difference between the groups. Those women who prepared during pregnancy and who encountered information about their child’s sleep scored lower in the BISQ-R (t = -4.07, p < 0.001 and t = -3.01, p < 0.01, respectively), and IS (t = -3.95, p < 0.01; t = -3.37, p < 0.01).

GLM model of women’s expectations about child’s sleep. Notes: Infant Sleep, Parental Perceptions, and Parental Behavior are subscales of the BISQ. Children—intended as a primiparous mother vs a mother with at least one child. Education—level of education achieved according to the Czech education system. Stress and anxiety—were measured using the DASS-21 questionnaire

Discussion

Poor quality of sleep is a serious problem during pregnancy. The prevalence varies between 29 and 76% (Gelaye et al., 2017; Mindell et al., 2015; Sedov et al., 2018). Although the possible negative impact on women`s and children`s psychological and physical health has been proven, it would seem that insufficient professional attention is paid to this topic in our country. In addition, other factors can have an impact on the quality of sleep as well as the psychological state of pregnant women. As far as the authors are aware, existing research inadequately explores the potential factors associated with and predictors of maternal sleep quality, along with their expectations regarding child sleep within a broader context. This study observed sleep quality, depression, anxiety and stress in women in their third trimester of pregnancy. The aim was to delineate these variables in relationship to circadian preference, sociodemographic data and mother`s anticipations regarding their infant`s sleep at six weeks after delivery. The study placed a significant emphasis on identifying factors that influence the sleep quality of pregnant women, and it also tracked predictors associated with maternal expectations regarding children`s sleep.

A recent meta-analysis indicates that sleep quality decreased from the second to the third trimester (Sedov et al., 2018). For this reason, we chose women in the third trimester of pregnancy for research purposes. Poor sleepers accounted for 64% of our sample. Sleep quality among our participants was related to depression, anxiety and stress. These results agree with studies that also confirmed that the sleep quality of pregnant women can be correlative to acutely experienced psychological discomfort (Alder et al., 2007; van de Loo et al., 2018; Volkovich et al., 2016). Sleep quality should be monitored during pregnancy for several reasons. First, poor sleep quality, stress, depression and anxiety during pregnancy can adversely affect the development of the fetus, the course of childbirth and the physical and psychological progress of the child (Alder et al., 2007; Dean et al., 2018; Graignic-Philippe et al., 2014). Second, the occurrence of depressive symptoms in pregnancy carries the risk of an increase in suicidal thoughts (Gelaye et al., 2017). Third, poor sleep quality can be a risk factor for depression during the postpartum period (Okun et al., 2013; Tomfohr et al., 2015; van de Loo et al., 2018).

Using GLM, we tried to reveal variables that predict sleep quality. The resulting model showed the three potential predictors of sleep quality: anxiety, week of pregnancy and circadian preferences. The findings about anxiety and the week of pregnancy confirm the previous conclusions of our study and others (see above). Pregnant women with an evening preference have a higher predisposition to postnatal depression and a higher risk of anxiety symptoms and sleep problems (Ashi et al., 2022; Merikanto et al., 2017; Obeysekare et al., 2020). It was also confirmed in our research that the lower the women scored in the MEQ (the more the evening type, the worse the quality of their sleep). Poor sleepers were among the evening types. The results of correlation (r) and the difference between groups (t) were significant, even after correction for multiple testing.

In addition, our research indicates answers to questions related to the relationship between widely researched variables (sleep quality, depression, anxiety) and marginally researched expectations regarding infant sleep. Unfortunately, we have not found a standardized method that meets our requirements and measures the expectations of a pregnant woman regarding the infant`s sleep. We used the BISQ-R questionnaire after agreement with the authors. Pregnant women answered the questions with an idea about what the child’s sleep could be after an elapse of six weeks of age. We chose this period deliberately. Postpartum involutional changes in the mother’s organism tend to be completed during this time. There is also a gradual stabilization of the child’s circadian rhythm (peak around 10–12 weeks) (Galland et al., 2012). In our research, women who already have at least one child expect better overall sleep for their child. Their assumptions about difficulties resulting from a child’s sleep are more optimistic. The number of children was the most significant variable that predicted the total score in the BISQ-R. It is interesting, however, that if we focused on comparing groups of women who were or were not preparing for childbirth and motherhood, the results were the opposite. Women who did not prepare and had not encountered information about a child’s sleep achieved higher scores on the BISQ-R. We can voice a hypothesis that sufficient information before childbirth and earlier maternal experiences can affect expectations. This means non-informed or multiparous women may have more positive expectations about the child’s sleep, and vice versa. Are these expectations more optimistic or, on the contrary, expectations that are more in line with reality? However, this hypothesis would need to be verified in follow-up research. We consider this factor to be relevant. It should not be neglected in future research. As indicated by earlier findings, it has been shown that unrealistic expectations about a child’s sleep can predict a mother’s sleep quality or mental health (Eastwood et al., 2012; Giallo et al., 2011).

Due to the scope of the research sample, we consider our research as a pilot (exploratory research design). Based on the findings, we recommend repeating the study with a larger research sample, ideally as a multi-state collaboration. Thanks to this, it would be possible to verify whether the BISQ-R can be used as a standard also for determining parents’ expectations about the child’s future sleep, as was intended in this study. Expanding research data in our state would also bring missing standards for our population. Furthermore, it could be beneficial to expand the range of other potential factors that may play a role in the results, such as the number of pregnancies, abortions, place of residence and others, in follow-up studies.

Limitations

First, we used a subjective method to determine sleep quality (PSQI). Although the PSQI is the most widely used method for measuring sleep quality, not only in pregnant women, in oncoming studies, it would be advisable to use objective methods, for example, actigraphy. We believe that the simultaneous use of subjective and objective methods is appropriate. Second, the concept of maternal expectation is under-researched. To the authors’ knowledge, we have not found a method that measures this issue. Therefore, after consultation with the authors of the BISQ-R questionnaire, we decided to use this method for our aim. Moreover, Cronbach`s alpha of BISQ-R total score was low. We assume that this may be a consequence of the fact that the total score is calculated as the average of three subscales that measure different aspects of sleep. For example, one parent may perceive a baby who wakes up once per night as highly problematic, whereas another may think it’s not an issue. In addition, the scores provided are based on the norms of a US sample because the Czech norms are absent. Third, only a slight percentage of women with evening circadian preferences were in our sample. The distribution did not follow a normal distribution. We used data transformation using the Box-Cox transformation in the analyses.

Conclusion

In total, 64% of women in our sample had poor sleep quality. These women scored higher on depression, anxiety and stress. Maternal expectations were more positive among women who had at least one child, who did not prepare for childbirth and motherhood and who had not been informed about the child’s sleep. We can hypothesize that sufficient information before childbirth and previous maternal experiences can influence expectations about a child’s sleep. This hypothesis will need to be verified in upcoming research. Ideally, it would be appropriate to execute a longitudinal study using objective and subjective methods concurrently and follow women before and during pregnancy, after childbirth and repeatedly during all pregnancies. We consider sleep quality, just as sufficient awareness of what is and is not ordinary child’s sleep, to be relevant factors contributing to women’s physical and psychological health. Prevention programs should also deal with these areas.

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study is available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Alder, J., Fink, N., Bitzer, J., Hosli, I., & Holzgreve, W. (2007). Depression and anxiety during pregnancy: A risk factor for obstetric, fetal and neonatal outcome? A critical review of the literature. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine, 20, 189–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767050701209560

American Psychological Association (APA). (2002). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. American Psychologist, 57, 1060–1073. Retrieved September 21, 2023, Available from the APA Web site: http://www.apa.org/ethics/code2002.html

Ashi, K., Levey, E., Friedman, L. E., Sanchez, S. E., Williams, M. A., & Gelaye, B. (2022). Association of morningness-eveningness with psychiatric symptoms among pregnant women. Chronobiology International, 39(7), 984–990. https://doi.org/10.1080/07420528.2022.2053703

Ball, H. L. (2003). Breastfeeding, bed-sharing, and infant sleep. Birth, 30(3), 181–188. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-536X.2003.00243.x

Bayer, J., Hiscock, H., Hampton, A., & Wake, M. (2007). Sleep problems in young infants and maternal mental and physical health. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 43, 66–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1754.2007.01005.x

Box, G. E. P., & Cox, D. R. (1964). An analysis of transformations. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological), 26(2), 211–252. Retrieved September 20, 2023, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2984418

Buysse, D. J., Reynolds, C. F., Monk, T. H., Berman, S. R., & Kupfer, D. J. (1989). The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Research, 28(2), 193–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4

Canário, C., & Figueiredo, B. (2017). Anxiety and depressive symptoms in women and men from early pregnancy to 30 months postpartum. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 35(5), 431–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2017.1368464

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbam. https://www.utstat.toronto.edu/~brunner/oldclass/378f16/readings/CohenPower.pdf

Chénier-Leduc, G., Béliveau, M.-J., Dubois-Comtois, K., Kenny, S., & Pennestri, M.-H. (2023). Parental depressive symptoms and infant sleeping arrangements: The contributing role of parental expectations. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 32(8), 2271–2280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-022-02511-x

Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16, 297–334.

Dean, D. C., 3rd., Planalp, E. M., Wooten, W., Kecskemeti, S. R., Adluru, N., Schmidt, C. K., Frye, C., Birn, R. M., Burghy, C. A., Schmidt, N. L., Styner, M. A., Short, S. J., Kalin, N. H., Goldsmith, H. H., Alexander, A. L., & Davidson, R. J. (2018). Association of prenatal maternal depression and anxiety symptoms with infant white matter microstructure. JAMA Pediatrics, 172(10), 973–981. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2132

Dias, C. C., Figueiredo, B., Rocha, M., & Field, T. (2018). Reference values and changes in infant sleep-wake behaviour during the first 12 months of life: A systematic review. Journal of Sleep Research, 27(5), e12654. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.12654

Eastwood, J. G., Jalaludin, B. B., Kemp, L. A., Phung, H. N., & Barnett, B. E. W. (2012). Relationship of postnatal depressive symptoms to infant temperament, maternal expectations, social support and other potential risk factors: Findings from a large Australian cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 12(1), 148. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-12-148

Facco, F. L., Kramer, J., Ho, K. H., Zee, P. C., & Grobman, W. A. (2010). Sleep disturbances in pregnancy. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 115, 77–83. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c4f8ec

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/bf03193146

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/brm.41.4.1149

Fárková, E., Novák, J. M., Manková, D., & Kopřivová, J. (2020). Comparison of Munich Chronotype Questionnaire (MCTQ) and Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire (MEQ) Czech version. Chronobiology International, 37(11), 1591–1598. https://doi.org/10.1080/07420528.2020.1787426

Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. Sage.

Galland, B. C., Taylor, B. J., Elder, D. E., & Herbison, P. (2012). Normal sleep patterns in infants and children: A systematic review of observational studies. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 16(3), 213–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2011.06.001

Gelaye, B., Addae, G., Neway, B., Larrabure-Torrealva, G. T., Qiu, C., Stoner, L., Luque Fernandez, M. A., Sanchez, S. E., & Williams, M. A. (2017). Poor sleep quality, antepartum depression and suicidal ideation among pregnant women. Journal of Affective Disorders, 209, 195–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.11.020

Giallo, R., Rose, N., & Vittorino, R. (2011). Fatigue, wellbeing and parenting in mothers of infants and toddlers with sleep problems. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 29(3), 236–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2011.593030

Graignic-Philippe, R., Dayan, J., Chokron, S., Jacquet, A.-Y., & Tordjman, S. (2014). Effects of prenatal stress on fetal and child development: A critical literature review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 43, 137–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.03.022

Horne, J. A., & Östberg, O. (1976). A self-assessment questionnaire to determine morningness-eveningness in human circadian rhythms. International Journal of Chronobiology, 4(2), 97–110.

Hutchison, B. L., Stone, P. R., McCowan, L. M. E., Stewart, A. W., Thompson, J. M. D., & Mitchell, E. A. (2012). A postal survey of maternal sleep in late pregnancy. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 12, 144. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-12-144

Kaya, İG., & Koçak, D. Y. (2023). The effects of restless legs syndrome on sleep and quality of life during pregnancy: A comparative descriptive study. Perinatal Journal, 31(1), 41–49. https://doi.org/10.2399/prn.23.0311008

Kuehner, Ch. (2017). Why is depression more common among women than among men? Lancet Psychiatry, 4(2), 146–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30263-2

Liu, Y., Zhang, L., Guo, N., & Jiang, H. (2021). Postpartum depression and postpartum post-traumatic stress disorder: prevalence and associated factors. BMC Psychiatry, 21(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03432-7

Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U

Lu, Q., Zhang, X., Wang, Y., Li, J., Xu, Y., Song, X., Su, S., Zhu, X., Vitiello, M. V., Shi, J., Bao, Y., & Lu, L. (2021). Sleep disturbances during pregnancy and adverse maternal and fetal outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2021.101436

Manková, D., Dudysová, D., Novák, J., Fárková, E., Janků, K., Kliková, M., Bušková, J., Bartoš, A., Šonka, K., & Kopřivová, J. (2021). Reliability and validity of the czech version of the pittsburgh sleep quality index in patients with sleep disorders and healthy controls. BioMed Research International, 5576348. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5576348

Merikanto, I., Paavonen, E. J., Saarenpää-Heikkilä, O., Paunio, T., & Partonen, T. (2017). Eveningness associates with smoking and sleep problems among pregnant women. Chronobiology International, 34(5), 650–658. https://doi.org/10.1080/07420528.2017.1293085

Mindell, J. A., Cook, R. A., & Nikolovski, J. (2015). Sleep patterns and sleep disturbances across pregnancy. Sleep Medicine, 16(4), 483–488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2014.12.006

Mindell, J. A., Gould, R. A., Tikotzky, L., Leichman, E. S., & Walters, R. M. (2019). Normative scoring system for the brief infant sleep questionnaire – revised (BISQ–R). Sleep Medicine, 63, 106–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2019.05.010

Moghadam, Z. B., Rezaei, E., & Rahmani, A. (2021). Sleep disorders during pregnancy and postpartum: A systematic review. Sleep Medicine Research, 12(2), 81–93. https://doi.org/10.17241/smr.2021.00983

Muscat, T., Obst, P., Cockshaw, W., & Thorpe, K. (2014). Beliefs about infant regulation, early infant behaviors and maternal postnatal depressive symptoms. Birth, 41(2), 206–213. https://doi.org/10.1111/birt.12107

O’Connell, M. A., Leahy-Warren, P., Khashan, A. S., Kenny, L. C., & O’Neill, S. M. (2017). Worldwide prevalence of tocophobia in pregnant women: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Obstetricia Et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 96(8), 907–920. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.13138

Obeysekare, J. L., Cohen, Z. L., Coles, M. E., Pearlstein, T. B., Monzon, C., Flynn, E. E., & Sharkey, K. M. (2020). Delayed sleep timing and circadian rhythms in pregnancy and transdiagnostic symptoms associated with postpartum depression. Translational Psychiatry, 10, 14. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-020-0683-3

Okun, M. L., Kline, Ch. E., Roberts, J. M., Wettlaufer, B., Glover, K., & Hall, M. (2013). Prevalence of sleep deficiency in early gestation and its associations with stress and depressive symptoms. Journal of Women’s Health, 22(12), 1028–1037. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2013.4331

Park, E. M., Meltzer-Brody, S., & Stickgold, R. (2013). Poor sleep maintenance and subjective sleep quality are associated with postpartum maternal depression symptom severity. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 16(6), 539–547. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-013-0356-9

Pauley, A. M, Moore, G. A., Mama, S. K., Molenaar, P., Symons Downs, D. (2020). Associations between prenatal sleep and psychological health: a systematic review. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 16(4. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.8248

Richardson, J. T. E. (2011). Eta squared and partial eta squared as measures of effect size in educational research. Educational Research Review, 6(2), 135–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2010.12.001

Sadeh, A. (2004). A brief screening questionnaire for infant sleep problems: Validation and findings for an Internet sample. Pediatrics, 113(6), e570–e577. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.113.6.e570

Sedov, I. D., Cameron, E. E., Madigan, S., & Tomfohr-Madsen, L. M. (2018). Sleep quality during pregnancy: A meta-analysis. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 38, 168–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2017.06.005

Silvestri, R., & Aricò, I. (2019). Sleep disorders in pregnancy. Sleep Science, 12(3), 232–239. https://doi.org/10.5935/1984-0063.20190098

Stremler, R., McMurray, J., & Brennenstuhl, S. (2020). Self-reported sleep quality and actigraphic measures of sleep in new mothers and the relationship to postpartum depressive symptoms. Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 18(3), 396–405. https://doi.org/10.1080/15402002.2019.1601629

Tomfohr, L. M., Buliga, E., Letourneau, N. L., Campbell, T. S., & Giesbrecht, G. F. (2015). Trajectories of sleep quality and associations with mood during the perinatal period. Sleep, 38(8), 1237–1245. https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.4900

Tsai, S.-Y., Lee, P.-L., Lin, J.-W., & Lee, C.-N. (2016). Cross-sectional and longitudinal associations between sleep and health-related quality of life in pregnant women: A prospective observational study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 56, 45–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.01.01

Van de Loo, K. F. E., Vlenterie, R., Nikkels, S. J., Merkus, P. J. F. M., Roukema, J., Verhaak, C. M., Roeleveld, N., & van Gelder, M. M. H. J. (2018). Depression and anxiety during pregnancy: The influence of maternal characteristics. Birth, 45(4), 478–489. https://doi.org/10.1111/birt.12343

Viswasam, K., Eslick, G. D., & Starcevic, V. (2019). Prevalence, onset and course of anxiety disorders during pregnancy: A systematic review and meta analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 255, 27–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.05.016

Volkovich, E., Tikotzky, L., & Manber, R. (2016). Objective and subjective sleep during pregnancy: Links with depressive and anxiety symptoms. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 19, 173–181. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-015-0554-8

Vilimovský, T., & Kučera, D. (n.d.). Czech version of DASS-21. Retrieved May 01, 2022, from http://www2.psy.unsw.edu.au/groups/dass/Czech/Vilimovsky%20Czech.htm

Wilson, D. L., Barnes, M., Ellett, L., Permezel, M., Jackson, M., & Crowe, S. F. (2011). Decreased sleep efficiency, increased wake after sleep onset and increased cortical arousals in late pregnancy. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 51(1), 38–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1479-828X.2010.01252.x

Yin, X., Sun, N., Jiang, N., Xu, X., Gan, Y., Zhang, J., … & Gong, Y. (2021). Prevalence and associated factors of antenatal depression: Systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Clinical Psychology Review, 83, 101932. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101932

Funding

Open access publishing supported by the National Technical Library in Prague. This publication was made possible thanks to targeted funding provided by the Czech Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports for specific research, granted to Palacký University Olomouc (IGA_FF_2022_054).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Denisa Manková, Soňa Švancarová and Eliška Štenclová. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Denisa Manková and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical standards

The research was approved by the Research Ethics Panel of the Faculty of Arts of the Palacký University in Olomouc, Czech Republic (protocol number 04/2022). The study protocol followed the international ethical standards of the American Psychological Association (APA, 2002).

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflicts of interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Manková, D., Švancarová, S. & Štenclová, E. Sleep, depression, anxiety, stress and circadian preferences among women in the third trimester. Are these variables related to mother’s expectations about their child’s sleep?. Curr Psychol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-05839-3

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-05839-3